Abstract

Clinical practice guidelines are designed to synthesize and disseminate the best available evidence to guide clinical practice. The goal is to increase high-quality care and reduce inappropriate interventions. Clinical practice guidelines that systematically review evidence and synthesize it into recommendations are important because the available scientific evidence is normally neither rapidly nor broadly incorporated into practice. It is important to understand and improve the impact of our American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation clinical practice guidelines on this uptake of scientific knowledge. Considering the barriers to guideline adherence is a central part of this. This understanding can guide clinicians, future guideline authors, and researchers when using guidelines, writing them, and planning clinically relevant research.

Keywords: clinical practice guidelines, quality improvement

Since 2004 the American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) has supported multidisciplinary development groups to use methodologic rigor and transparency to develop and share 12 published clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) as well as 5 interval CPG updates. Significant resources and time have been applied to this process. These CPGs provide key action statements (KASs) targeted to improving the quality of care delivered, as well as supporting text. Additionally, each KAS has an action statement profile that clarifies the incorporation of aggregate evidence quality, harm versus benefit, rationale for intentional vagueness, development group values, and patient preference.

Adherence

Understanding the impact of CPGs is important to future efforts in their development. Despite intense efforts to disseminate CPGs, previous studies have shown that, in general, uptake of recommendations in CPGs is limited.1 This may be true for some but not all AAO-HNSF CPGs. There is a wide variation in reported adherence to AAO-HNSF KASs, ranging from 0% to 98.9%.2–8

Barriers to Adherence

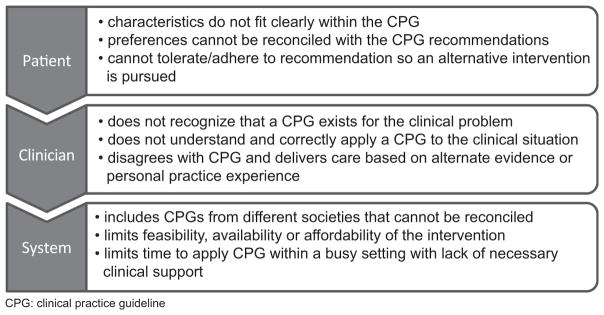

Clinicians do not intentionally provide poor-quality care. There are several patient, clinician, and system barriers to following CPGs (Figure 1). Some of these are fixed, while others are modifiable.

Figure 1.

Select patient, clinician, and system barriers to adherence to clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).

Patient

CPGs consolidate a vast literature into focused and digestible KASs designed for the busy clinician. This sharpening of the focus naturally limits the breadth of clinician experience as well as patient complexity. These variations within clinical practice will always be present. Although some patients should not be contorted to fit into a certain KAS, the applicability of a CPG should be shared with relevant patients so that they can be well informed for shared medical decision making.

Clinician

Many AAO-HNS members are engaged with their academy’s CPGs. Setabutr et al found that 88% of pediatric otolaryngology AAO-HNS members had read both the tonsillectomy and polysomnography for sleep-disordered breathing guidelines within 3 to 12 months of publication.2 In contrast, among primary care clinicians, there was low (1.9%) self-reported use of the AAO-HNSF otitis media with effusion CPG, despite representation of the American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians in the CPG development.8 Moreover, all CPGs are openly accessible without subscription fees to the public at the SAGE Publications website (http://journals.sagepub.com/home/oto). The CPGs—as well as executive summaries, podcasts of relevant discussions, plain language summaries, patient handouts, and other resources—are also available to the public at http://www.entnet.org/content/clinical-practice-guidelines. Increased awareness of these resources, especially through other societies’ websites, newsletters, and journal announcements, could enhance awareness, understanding, and uptake of CPGs.

System

The reported adherence to the AAO-HNSF CPG strong recommendation against routine perioperative antibiotics for pediatric tonsillectomy ranges from 64% to 94% over 4 health systems.2–4,6 Of these, Milder et al found the largest increase in adherence from the time before CPG publication to that afterward (3%–94%).4 This large change was attributed to “efforts within this particular otolaryngology group to standardize tonsillectomy practices according to the new guidelines, reflecting a successful quality improvement initiative.”4 This finding supports that clinic, hospital, or system-wide interventions to enable adherence to CPGs can be effective and should be pursued.

The AAO-HNSF promotes a broad spectrum of stakeholder involvement in CPG development to enhance validity.9 Additionally, groups that are actively involved with the CPG development will be more likely to enter future collaborations rather than create separate and potentially conflicting CPGs.

Adherence Assessment

Research to assess adherence to CPGs and its barriers has limitations. Retrospective chart reviews tend to be limited to 1 center, thus narrowing their generalizability. Their advantages include the patient characteristics, decision-making process, and counseling efforts gleaned from the records, which allow better understanding of reasons for adherence as well as nonadherence.

Surveys reach a broader population but rely on accurate recall and self-reporting. The actual patient care remains unknown. Clinicians who are on membership-generated email lists and respond to surveys are likely different from those who do not receive or respond to surveys. These biases limit the role of surveys in understanding adherence. However, surveys can be valuable for targeted questions regarding reasons for nonadherence, which can then be addressed in future quality improvement efforts, research, and CPGs.

Many large, multicenter health care databases are available to objectively evaluate practice patterns. Analyses that are well designed to minimize the introduction of bias can efficiently assess the adherence to CPGs. Sajisevi et al used this approach effectively with a commercial claims database to assess practice patterns in pediatric tympanostomy tube placement immediately prior to the 2013 CPG.10 These databases can help identify clinical areas that may benefit from CPG development, assess adherence to existing CPGs, and clarify the effects of CPG-driven clinical practice.

Conclusion

CPGs are only as good as their uptake, and this can be improved through the evaluation of their effects and the removal of barriers to adherence. Clear, clinically relevant CPGs with rigorous methodology are the foundation for their effective uptake. Dissemination and access to the CPGs are also important. As the focus on providing the best-quality health care increases, we can expect an increasing role of CPG adherence in the assessment of clinical care quality. Even if this is not the primary intent of CPGs, it makes the development of high-quality CPGs and the removal of barriers to using CPGs more important.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: Guidelines International Network Scholars Program. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders training grant T32 DC013018-03.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Marisa A. Ryan, complete authorship: drafting, editing, and final approval.

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

Sponsorships: None.

References

- 1.Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setabutr D, Adil EA, Chaikhoutdinov I, et al. Impact of the pediatric tonsillectomy and polysomnography clinical practice guidelines. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78:517–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padia R, Olsen G, Henrichsen J, et al. Hospital and surgeon adherence to pediatric tonsillectomy guidelines regarding perioperative dexamethasone and antibiotic administration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153:275–280. doi: 10.1177/0194599815582169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milder EA, Rizzi MD, Morales KH, et al. Impact of a new practice guideline on antibiotic use with pediatric tonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:410–416. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darrat I, Yaremchuk K, Payne S, et al. A study of adherence to the AAO-HNS “Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis”. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:338–352. doi: 10.1177/014556131409300813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahant S, Hall M, Ishman SL, et al. Association of national guidelines with tonsillectomy perioperative care and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;136:53–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witsell DL, Khoury T, Schulz KA, et al. Evaluation of compliance for treatment of sudden hearing loss: a CHEER Network Study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:48–55. doi: 10.1177/0194599816650175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey M, Bowe SN, Laury AM. Clinical practice guidelines: whose practice are we guiding? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:373–375. doi: 10.1177/0194599816655145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenfeld RM, Shiffman RN, Robertson P. Clinical practice guideline development manual, third edition: a quality-driven approach for translating evidence into action. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148:S1–S55. doi: 10.1177/0194599812467004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sajisevi M, Schulz K, Cyr DD, et al. Nonadherence to guideline recommendations for tympanostomy tube insertion in children based on mega-database claims analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:87–95. doi: 10.1177/0194599816669499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]