Abstract

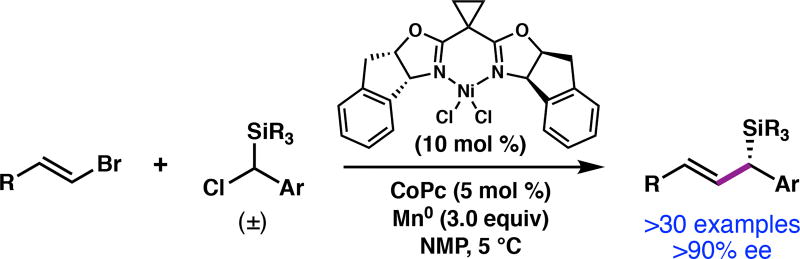

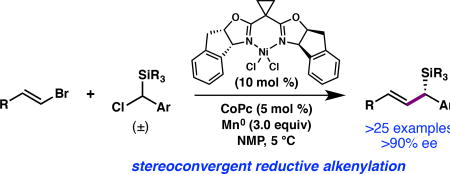

An asymmetric Ni-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling has been developed to prepare enantioenriched allylic silanes. This enantioselective reductive alkenylation proceeds under mild conditions and exhibits good functional group tolerance. The chiral allylic silanes prepared here undergo a variety of stereospecific transformations, including intramolecular Hosomi-Sakurai reactions, to set vicinal stereogenic centers with excellent transfer of chirality.

TOC graphic

Organosilanes are valuable organic materials with applications in medicinal chemistry,1 materials science,2 and as reagents for organic synthesis.3 In particular, chiral allylic silanes are versatile synthetic reagents that engage in a variety of highly stereoselective reactions. For example, the Hosomi-Sakurai reaction4 is a powerful method for C–C bond formation that provides homoallylic alcohols with excellent transfer of chirality when enantioenriched allylic silanes are used.5,6 Despite the utility of this and related transformations, the enantioselective preparation of chiral allylic silanes often requires multistep sequences, or the incorporation of specific functional groups to direct the formation of the C(sp3)-Si bond. Here we describe a Ni-catalyzed asymmetric reductive cross-coupling to directly prepare enantioenriched allylic silanes from simple, readily available building blocks (Figure 1). The resulting chiral allylic silanes undergo a variety of post-coupling transformations with high levels of chirality transfer.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of Chiral Allylic Silanes by Enantioselective Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling

Chiral allylic silanes are most commonly prepared through diastereoselective or stereospecific transformations,7 which include the Claisen rearrangement of vinyl silanes,8 bis-silylation of allylic alcohols,9 silylene insertion of allylic ethers,10 and the alkenylation of 1,1-silaboronates.11 In addition, several enantioselective transition metal-catalyzed reactions have been developed, including the hydrosilylation of dienes,12 the silylboration of allenes13, the insertion of metal carbenoids into Si-H bonds,14 and conjugate addition15 and allylic substitution16 reactions. Asymmetric transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling, in which the critical silicon-bearing C(sp3) stereogenic center is established in the C–C bond forming step, represents an alternative and highly modular approach to chiral allylic silanes. Indeed, the first synthesis of an enantioenriched chiral allylic silane was the Pd-catalyzed asymmetric cross-coupling between α-(trimethylsilyl)benzylmagnesium bromide and 1-bromo-1-propene reported by Kumada and coworkers in 1982.5a However, this method employs Grignard reagents as coupling partners, which are not stable to long-term storage and decreases the functional group compatibility of the reaction. We envisioned that a Ni-catalyzed asymmetric reductive alkenylation would address this limitation,17 in that the required (chlorobenzyl)silanes are bench stable compounds and these reactions typically exhibit good functional group tolerance. Thus, a Ni-catalyzed reductive alkenylation could provide chiral allylic silanes that were not readily accessible by other methods.

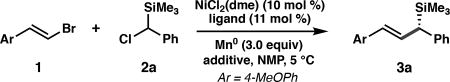

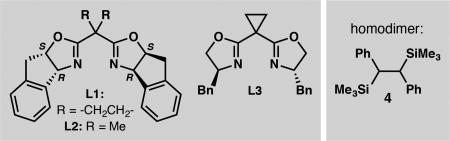

Our investigations began with the coupling between (E)-1-(2-bromovinyl)-4-methoxybenzene (1) and (chloro(phenyl)methyl)trimethylsilane (2a) using chiral bis(oxazoline) ligand L1, which was optimal in our previously developed enantioselective reductive alkenylation reaction (Table 1).14 A screen of reaction parameters revealed that when the reaction is conducted at 5 °C with with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) as the solvent,18 allylic silane 3a was formed in low yield, but with high enantioselectivity (entry 1). We hypothesized that the presence of the bulky silyl group impeded the oxidative addition of 2a to the Ni catalyst. The addition of cobalt(II) phthalocyanine (CoPc), a cocatalyst that enables the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling of benzyl mesylates by facilitating alkyl radical generation,19 doubled the yield of 3a (entry 3). The yield of 3a increased when excess vinyl bromide was used (entries 3–5); since the use of 2.0 equiv 1 proved most generally robust across a range of substrates, these conditions were used to evaluate the scope of the reaction (see Tables 2 and 3). A screen of other bis(oxazoline) ligands, e.g. L2 and L3, determined that L1 provided the highest enantioselectivity (entries 6–7). The use of isolated complex L1·NiCl2 gave 3a in comparable yield to the in situ generated catalyst (entry 8). Control experiments confirmed that NiCl2(dme), ligand, and Mn0 are required to form 3a.15 To demonstrate scalability, the cross-coupling was conducted on a 6.0 mmol scale, delivering 1.3 g of 3a in 74% yield and 97% ee.

Table 1.

Optimization of Allylic Silanes

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entrya | ligand | equiv 1 | additiveb | yield 4 (%)c |

yield 3a (%)c |

ee 3a (%)d |

| 1 | L1 | 1.0 | none | 26 | 20 | 96 |

| 2 | L1 | 1.0 | NaI | 22 | 26 | 97 |

| 3 | L1 | 1.0 | CoPc | 13 | 51 | 96 |

| 4 | L1 | 1.5 | CoPc | 9 | 64 | 97 |

| 5 | L1 | 2.0 | CoPc | 8 | 69 | 97 |

| 6 | L2 | 2.0 | CoPc | 22 | 14 | 41 |

| 7 | L3 | 2.0 | CoPc | 9 | 49 | −90 |

| 8 e | L1 | 2.0 | CoPc | 9 | 70 | 97 |

Reactions conducted under N2 on 0.1 mmol scale for 48 h.

NaI = 0.5 equiv; CoPc = 5 mol %.

Determined by 1H NMR versus an internal standard.

Determined by SFC using a chiral stationary phase.

10 mol % preformed (3R,8S)-L1·NiCl2 complex used.

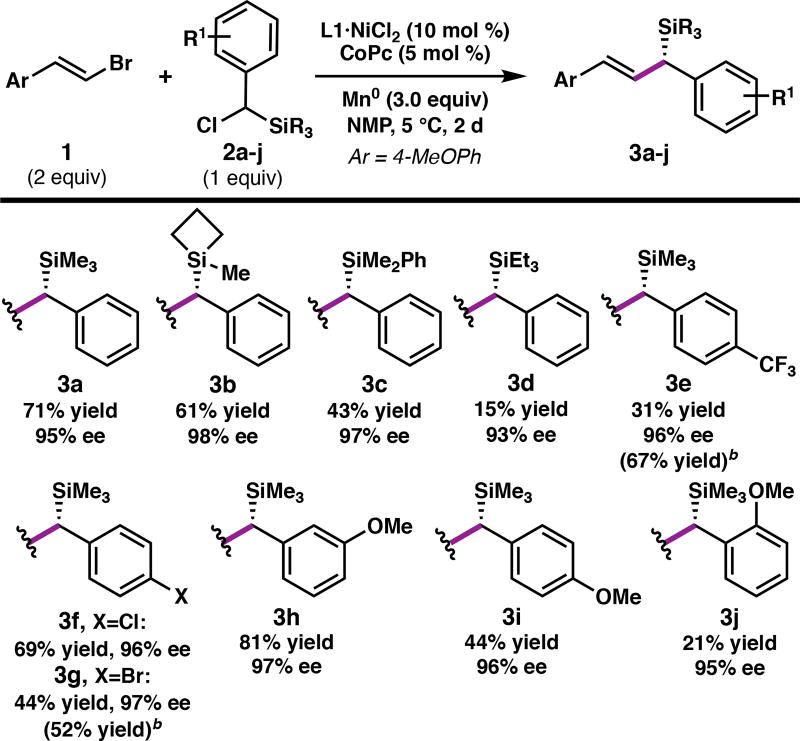

Table 2.

Chlorobenzyl Silane Scopea

Reactions conducted on 0.2 mmol scale under N2. Isolated yields; ee is determined by SFC using a chiral stationary phase.

Yield determined by 1NMR versus an internal standard.

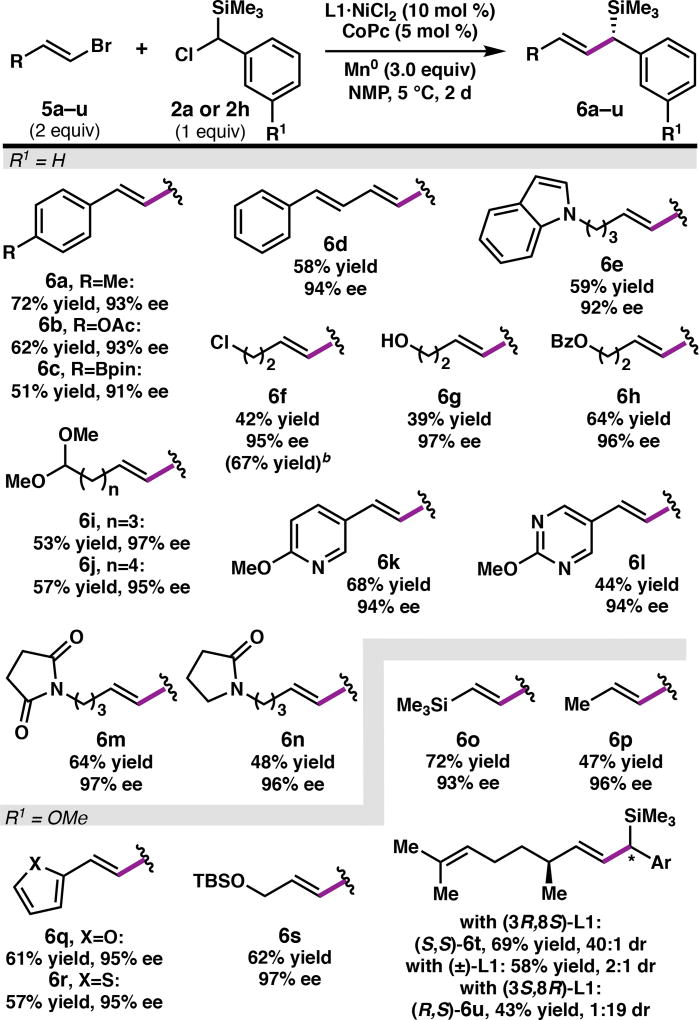

Table 3.

Vinyl Bromide Scopea

Reactions conducted on 0.2 mmol scale under N2. Isolated yields are provided; ee is determined by SFC or HPLC using a chiral stationary phase.

Yield determined by 1NMR versus an internal standard.

With the optimized conditions in hand, the scope of the silane was investigated (Table 2). Whereas strained silacy-clobutane20 3b was prepared in good yield and excellent ee, the corresponding triethylsilane 3d was formed in poor yield, presumably due to the increased steric encumbrance at silicon. Substrates bearing either electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups on the arene cross-coupled with universally high ee; however, in some cases the yield was diminished due to instability of the products (3e, 3g). The presence of an ortho substituent on the arene also decreased the yield of the cross-coupling product (3j).

The reaction tolerates a diverse array of functional groups on the alkenyl bromide partner (Table 3),21 including aryl boronates (6c), esters (6b, 6h), imides (6m), amides (6n), alkenyl silanes (6o), and alkyl halides (6f). For greasy substrates, m-methoxy silane 2h was used as the coupling partner to facilitate product purification (6o–6u). Alkyl-substituted alkenyl bromides performed comparably to styrenyl bromides; however, a limitation of the reaction is that Z-alkenes and tri- and tetra-substituted alkenyl bromides failed to react. By changing which enantiomer of L1 is employed, diastereomeric polyenes 6t and 6u were prepared, although the yield is decreased with the mismatched (3S,8R)-L1 catalyst. Finally, alkenyl bromides bearing furan (6q), thiophene (6r), pyridine (6k), pyrimidine (6l), and indole (6e) heterocycles could be cross-coupled, giving the corresponding allylic silanes in high ee. Functional groups that were not well tolerated include aldehydes and nitriles.22

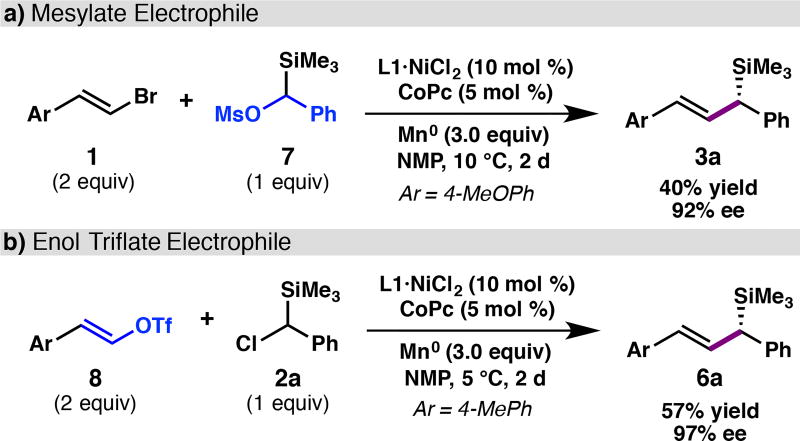

Although halide electrophiles were the primary focus of this study, oxygen-based electrophiles were also evaluated. We were pleased to find that mesylate 7 provided 3a in 45% yield and 92% ee; the lower yield was due to incomplete conversion of the starting material (Scheme 1a). Enol triflate 8 underwent cross-coupling to afford 6a in 57% yield, again with excellent enantioselectivity (Scheme 1b). Although the yields were modest, we note that these reactions were conducted under the conditions developed for the organic halides with minimal re-optimization.

Scheme 1.

Reactions of Oxygen-Based Electrophiles

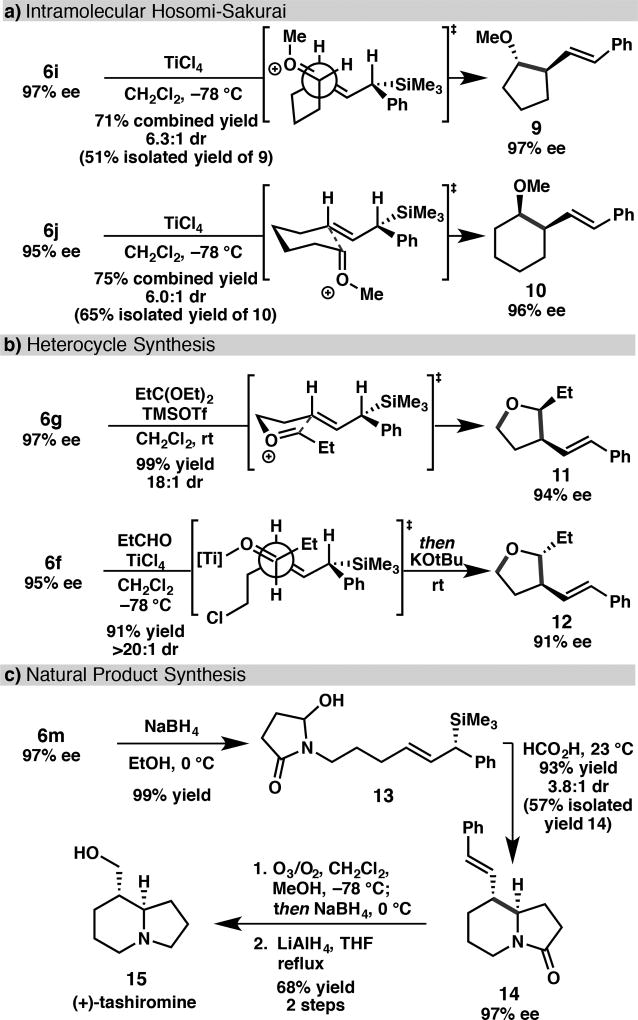

This reductive cross-coupling provides rapid access to functionalized chiral allylic silanes that are useful in a variety of synthetic transformations.23,24 For example, allylic silanes 6i and 6j, which contain pendant acetals, undergo stereospecific TiCl4-mediated intramolecular cyclization to form the 5- and 6-membered rings 9 and 10, respectively (Scheme 2a). The observed absolute and relative stereochemistry is consistent with an anti-SE’ mode of addition, which gives rise to the trans-substituted 5-membered ring and the cis-substituted 6-membered ring.25,26,27 Either the 2,3-cis or 2,3-trans tetrahydrofurans can be prepared by Lewis-acid mediated cyclizations of alcohol 6g or chloride 6f, respectively; both proceed with excellent transfer of chirality (Scheme 2b).5b,28 The utility of the method was further demonstrated in a concise enantioselective synthesis of (+)-tashiromine (Scheme 2c).29 Sodium borohydride reduction of imide 6m provided aminal 13, which upon exposure to formic acidcyclized to form bicycle 14 in 93% yield as a 3.8:1 mixture of diastereomers.30 The major diastereomer was isolated in 57% yield and 97% ee. Ozonolysis and reduction of the amide provided (+)-tashiromine.

Scheme 2.

Stereospecific Reactions of Chiral Allylic Silanes

In summary, a highly enantioselective cross-coupling reaction has been developed for the preparation of chiral allylic silanes. The reactions proceed under mild conditions and tolerate a variety of functional groups. The enantioenriched allylic silanes undergo several stereospecific transformations with high transfer of chirality, which we anticipate will prove useful in an array of synthetic contexts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Virgil and the Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis for access to analytical equipment. We also thank Dr. Michael K. Takase and Mr. Lawrence M. Henling for assistance with X-ray crystallography, as well as Dr. Mona Shahgholi and Naseem Torian for assistance with mass spectrometry measurements. Fellowship support was provided by the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship, J. L. H., A. H. C., Grant No. DGE-1144469) and Caltech SURF program (Richard H. Cox and John Stauffer Fellowships, C. M. O.). S. E. R. is an American Cancer Society Research Scholar and Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator. Financial support from the NIH (R35GM118191-01; GM111805-01) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental procedures, characterization and spectral data for all compounds, and crystallographic data (CIF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Showell GA, Mills JS. Drug. Discov. Today. 2003;8:551. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02726-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Min GK, Hernandez D, Skrydstrup T. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:457. doi: 10.1021/ar300200h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Franz AK, Wilson SO. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:388. doi: 10.1021/jm3010114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auner N, Weis J, editors. Organosilicon Chemistry V: From Molecules to Materials. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reviews: Chan TH, Wang D. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:995.Masse CE, Panek JS. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:1293.Fleming I, Barbero A, Walter D. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:2063. doi: 10.1021/cr941074u.Chabaud L, James P, Landais Y. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004;15:3173.

- 4.(a) Hosomi A, Sakurai H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:1295. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hosomi A, Endo M, Sakurai H. Chem. Lett. 1976;5:941. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kira M, Kobayashi M, Sakurai H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:4081. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kira M, Sato K, Sakaurai H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:257. [Google Scholar]; (d) Chemler SR, Roush WR. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3800. doi: 10.1021/jo0267908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seminal reports: Hayashi T, Konishi M, Ito H, Kumada M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4962.Hayashi T, Konishi M, Kumada M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:4963.Hayashi T, Konishi M, Okamoto Y, Kabeta K, Kumada M. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:3772.

- 6.(a) Jain NF, Takenaka N, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:12475. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hu T, Takenaka N, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9229. [Google Scholar]; (c) Berger R, Duff K, Leighton JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5686. doi: 10.1021/ja0486418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Park PK, O’Malley SJ, Schmidt DR, Leighton JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2796. doi: 10.1021/ja058692k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kim H, Ho S, Leighton JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6517. doi: 10.1021/ja200712f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recent catalytic asymmetric methods to prepare chiral, non-allylic silanes: Chen D, Zhu D-X, Xu M-H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1498. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12960.Kan SBJ, Lewis RD, Chen K, Arnold FH. Science. 2016;354:1048. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6219.Gribble MW, Jr, Pirnot MT, Bandar JS, Liu RY, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:2192. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b13029.

- 8.(a) Sparks MA, Panek JS. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:3431. [Google Scholar]; (b) Panek JS, Clark TD. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:4323. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suginome M, Matsumoto A, Ito Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3061. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourque LE, Cleary PA, Woerpel KA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12602. doi: 10.1021/ja073758s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Binanzer M, Fang GY, Aggarwal VK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4264. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aggarwal VK, Binanzer M, Carolina de Ceglie M, Gallanti M, Glasspoole BW, Kendrick SJF, Sonawane RP, Vazquez-Romero A, Webster MP. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1490. doi: 10.1021/ol200177f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T, Han JW, Takeda A, Tang J, Nohmi K, Mukaide K, Tsuji H, Uozumi Y. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2001;343:279. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohmura T, Taniguchi H, Suginome M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13682. doi: 10.1021/ja063934h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Davies HML, Hansen T, Rutberg J, Bruzinski PR. Tett. Lett. 1997;38:1741. [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu J, Chen Y, Panek JS. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2112. doi: 10.1021/ol100604m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Shintani R, Ichikawa Y, Hayashi T, Chen J, Nakao Y, Hiyama T. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4643. doi: 10.1021/ol702125q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee K-S, Wu H, Haeffner F, Hoveyda AH. Organomet. 2012;31:7823. doi: 10.1021/om300790t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kacprzynski MA, May TL, Kazane SA, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:4554. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Cherney AH, Reisman SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14365. doi: 10.1021/ja508067c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Suzuki N, Hofstra JL, Poremba KE, Reisman SE. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2150. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.See Supporting Information for additional reaction optimization data.

- 19.Ackerman LKG, Anka-Lufford LL, Naodovic M, Weix DJ. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:1115. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03106g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto K, Oshima K, Utimoto K. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:7152. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The absolute stereochemistry of 6c was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction. The stereochemical assignment of all other products were made by analogy.

- 22.Use of (E)-4-(2-bromovinyl)benzaldehyde or (E)-4-(2-bromovinyl)benzonitrile provide the cross-coupled product in 0% and 34% yield, respectively.

- 23.The allylic silanes can also be employed in standard Hosomi-Sakurai crotylation reactions with excellent transfer of chirality. See Supporting Information for details.

- 24.The photoredox-catalyzed trifluoromethylation of chiral allylic silanes has also been reported: Mizuta S, Engle KM, Verhoog S, Galicia-López O, O’Buill M, Médebielle M, Wheelhouse K, Rassias G, Thompson AL, Gouverneur V. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1250. doi: 10.1021/ol400184t.

- 25.An SN2-type mechanism is also consistent with the stereochemical outcome. Denmark SE, Willson TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:3475.

- 26.Diastereomers were assigned by comparison to synthetic standards. See Supporting Information.

- 27.Wu J, Pu Y, Panek JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:18440. doi: 10.1021/ja3083945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suginome M, Iwanami T, Ito Y. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6096. doi: 10.1021/jo981173y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) McElhinney AD, Marsden SP. Synlett. 2005;16:2528. [Google Scholar]; (b) Park Y, Schindler CS, Jacobsen EN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14848. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b09736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Hiemstra H, Sno MHAM, Vijn RJ, Speckamp WN. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:4014. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hubert JC, Wijnberg JBPA, Speckamp WN. Tetrahedron. 1975;31:1437. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.