Abstract

Objective

To perform a prospective non-randomized comparison of the effectiveness and safety of combined neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant treatment with the standard multiple-day cisplatin regimen for the prevention of cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

Methods

Patients being administered 3-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy (25 mg/m2/d) who had never received aprepitant were given either the standard regimen (tropisetron and dexamethasone) or the aprepitant regimen (aprepitant plus tropisetron and dexamethasone). The primary endpoint was the complete response (CR) in the overall phase (OP, 0–120 h) between the combined aprepitant triple regimen group and the standard group. Secondary endpoints were the CR in the acute phase (AP, 0–24 h) and delay phase (DP, 25–120 h) between the two groups. The first time of vomiting was also compared by Kaplan–Meier curves. The impact of CINV on the quality of life was assessed by the Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE). Aprepitant-related adverse effects (AEs) were also recorded.

Results

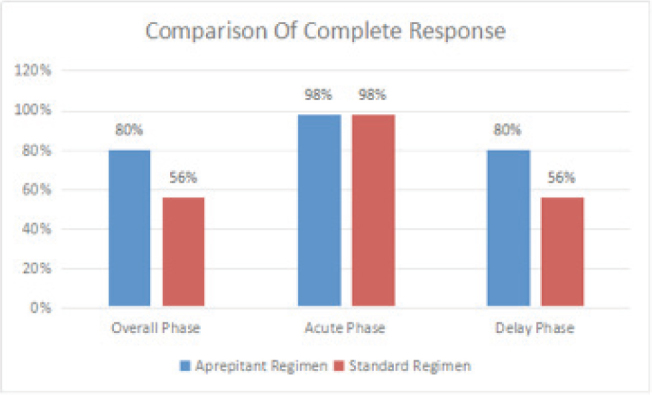

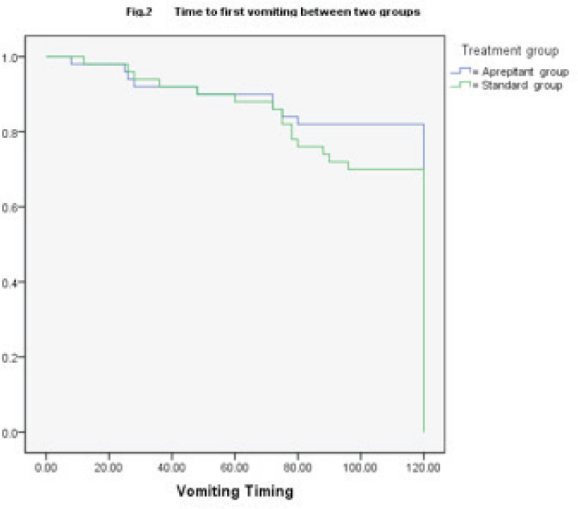

A CR was achieved by 80.0% in the aprepitant group compared with 56.0% in the standard group during the OP (P =0.018)as well as during the DP. However, during the AP, the aprepitant and standard therapy groups achieved identical CR rates (98.0%, P =1.000). A longer time to first emesis was documented for the aprepitant group than for the standard group. No effect of CINV on quality of life as assessed by FLIE was reported by 44.7% of aprepitant therapy patients and 24.0% of standard therapy patients (P=0.035). The main aprepitant-related AEs were fatigue and constipation, but there was no significant difference between groups.

Conclusion

Combined aprepitant therapy is recommended for the prevention of multiple-day CINV because of its improved CINV control rate and safety.

Keywords: Aprepitant, CINV, Multiple-day cisplatin chemotherapy

1. Introduction

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimens play an important role in cancer treatment, and a higher platinum dose delivery was shown to be beneficial at maintaining treatment efficacy [1]. However, it may decrease patient quality of life and affect chemotherapy dependence if cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) are not sufficiently prevented [2,3]. Although a combination of aprepitant, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, and dexamethasone (DXM) showed high efficacy in single-day cisplatin chemotherapy in the aprepitant multinational randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, the combination of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone remains a standard in multiple-day chemotherapy (MDC) [4,5,6]. With the aim of overcoming CINV, we conducted a non-randomized study to evaluate the efficacy of aprepitant combined with the standard regimen in patients receiving 3-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

Patients older than 18 years with a Karnofsky performance scale ≥60 scheduled to receive 3-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy (25 mg/m2/d) were enrolled in the study. All patients had histologically confirmed solid tumors. Females of childbearing potential had negative beta human chorionic gonadotropin blood tests. Primary exclusion criteria were: evidence of alcohol abuse, symptomatic primary or metastatic central nervous system metastasis, the administration of chemotherapy of moderate or high emetogenicity within the past 6 days, the scheduled administration of radiation therapy to the abdomen/pelvis within 1 week or chemotherapy within 3 weeks, the scheduled administration of single-day cisplatin chemotherapy, active infection or other uncontrolled disease, concurrent medical conditions precluding dexamethasone administration, and abnormal laboratory values including: white blood cell count <3,000/mm3 and absolute neutrophil count <1,500/mm3, platelet count <100,000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase >2.5 X upper limit of normal (ULN), alanine transaminase >2.5 x ULN, bilirubin >1.5 x ULN, or creatinine >1.5 x ULN. Patients were stratified into the aprepitant regimen group or control group according to clinical characteristics such as gender, age, alcohol use, and history of motion sickness.

2.2. Study design and medications

This non-randomized study was conducted at the Medical Oncology Department of Ordos Central Hospital in Inner Mongolia, China. From June 2014 to December 2016, patients were consecutively included if they received 3-day cisplatin-based chemotherapy (25mg/m2/d) and had not been previously treated with aprepitant. The study was approved by the local ethics committee and all patients gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Patients in the control group received an injection of tropisetron hydrochloride (Beijing Shuanglu Pharmaceutical Co.Ltd., China) and aprepitant (EMEND, MSD Sharp & Dohme, Haar, Germany). The medication procedure is listed in Table 2. Dexamethasone was reduced to half dosage in the aprepitant group because of the previously demonstrated inhibition of CYP3A4 by aprepitant in DXM pharmacokinetics [7].

Table 2.

The Medication Procedures

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | |

| aprepitant125mg po | aprepitant80mg po | aprepitant80mg po | ||

| aprepitant group | tropisetron5mg iv | tropisetron5mg iv | tropisetron5mg iv | |

| dexamethasone6mg po | dexamethasone3.75mg po | dexamethasone3.75mg po | dexamethasone3.75mg po | |

| standard group | tropisetron5mg iv | tropisetron5mg iv | tropisetron5mg iv | |

| dexamethasone7.5mg po | dexamethasone10.5mg po | dexamethasone7.5mg po | dexamethasone7.5mg po | |

Table 1.

Patients’ baseline characteristics [n(%)]

| Characteristics | Aprepitant regimen(n=50) | Standard therapy (n=50) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | |||

| Mean | 54.9±11.0 | 57.3±9.2 | 0.546 |

| Gender | 0.139 | ||

| Female | 21(42.0) | 13(26.0) | |

| Male | 29(58.0) | 37(74.0) | |

| History of motion sickness | 4(8.0) | 2(4.0) | 0.678 |

| History of nausea with pregnancy in female | 16(57.1) | 8(40.0)* | 0.713 |

| History of vomiting with pregnancy in female | 7(25.0) | 3(15.0)* | 0.713 |

| Alcohol use | 0.106 | ||

| No consumption | 28(56.0) | 16(32.0) | |

| <1 drinks per week | 8(16.0) | 14(28.0) | |

| 1-4 drinks per week | 2(4.0) | 2(4.0) | |

| ≥4drinks per week | 12(24.0) | 18(36.0) | |

| Smoking status | 0.580 | ||

| No Smoking | 22(44.0) | 17(34.0) | |

| ≥400 | 21(42.0) | 24(48.0) | |

| 0~400 | 7 (14.0) | 9 (18.0) | |

| Type of malignance | 0.423 | ||

| Lung cancer | 24(48.0) | 29(58.0) | |

| Others | 26(52.0) | 21(42.0) | |

| Chemotherapy cycle | 0.082 | ||

| 1 | 19(38.0) | 19(38.0) | |

| 2-3 | 26(52.0) | 18(36.0) | |

| ≥4 | 5 (10.0) | 13(26.0) |

P values were generated using Fisher’s exact test for characteristics with two groups and with the chi-square test for characteristics with mutiple groups

HNPCC: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

A female patient was without pregnancy history

2.3. Procedures and assessments

Patients have recorded and self-reported times and dates of vomiting or retching episodes, and use of rescue therapy from the time of chemotherapy infusion (0 h) until day 6. Patients were contacted on the mornings of days 2–6 to ensure compliance. Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) questionnaire scoring was self-administered early on day 6, directly following the completion of the final self-reports [8]. FLIE is a validated emesis- and nausea-specific questionnaire with nine nausea domain questions (items) and nine vomiting domain questions (items) [9,10]; ‘no impact of CINV on daily life’ represented mean scores >6 on a 7-point scale (>108 in total).

All patients underwent post-treatment examination on days 6–8 and follow-up on days 19–21 to record the occurrence of adverse events (AE) related to aprepitant treatment.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The sponsor managed the data and performed the analyses for this study. The primary endpoint for the efficacy analysis was the proportion of patients with a complete response (CR), defined as no vomiting or use of rescue therapy. Secondary endpoints included CR in the acute phase (AP, 0–24 h following chemotherapy) and the delay phase (DP, 24–120 h following chemotherapy), no vomiting (vomiting, dry heaves, or retching) in any phase, the impact of CINV on daily life during the overall phase (OP, FLIE questionnaire total score >108), and the time to first vomiting.

Treatment comparisons were made using logistic regression models that included terms for treatment, gender, age, alcohol use, and history of motion sickness. All comparisons used a two-sided significance level of 5%. Tests of significance were based on logistic regression models, and nominal P values were reported. Kaplan–Meier curves of time to first emesis were constructed for both groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the percentage of patients who achieved CR or experienced aprepitant-related AEs between the two groups.

3. Results

3.1. Patients

A total of 100 patients completed the clinical observation. Of these, 50 received the aprepitant triple regimen, and the remaining 50 received the standard regimen (control group). Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two groups. Primary cancer diagnoses were also similar, with lung cancer being the most common disease. No significant differences between groups were reported for alcohol use, history of motion sickness, or vomiting associated with pregnancy. Only female patients were assessed for nausea or vomiting during pregnancy.

3.2. Efficacy

A CR during the OP (primary endpoint) was exhibited by 80.0% (40/50) of patients receiving the aprepitant triple regimen and 56.0% (28/50) of those receiving the standard regimen (P =0.018; Figure 1). Similarly, CR during the DP was significantly higher in the aprepitant regimen group than in the standard therapy group (80.0% vs. 56.0%, P = 0.018). During the AP, however, the aprepitant and standard therapy groups exhibited identical CR rates (98.0%, P =1.000). Within the aprepitant group, the proportion of patients achieving a CR was highest in males (93.1% [27/29]) versus females (61.9% [13/21]) (P=0.011). Moreover, a higher treatment benefit in the standard group was also observed in males (70.3% [26/37]) compared with females (13.3% [2/15]) (P=0.000).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the complete response rate between the two groups

Figure 2.

Comparison of time to first vomiting between the two groups

3.3. Comparison of FLIE index

During the OP, a higher percentage of no vomiting was reported in the aprepitant regimen group than in the standard regimen group (82.0% [41/50] vs 70.0% [35/50], respectively), although this was not significant (P=0.241). Fewer uses of rescue treatment were reported in the aprepitant regimen group than in the standard regimen group (6.0%vs. 14.0%, respectively, P =0.318) during the OP. More patients taking the aprepitant regimen reported no vomiting and no significant nausea compared with the standard regimen group, though the difference did not reach significance during the OP (36.0% vs. 30.0%, P = 0.318).

According to FLIE, reports of no impact of CINV on daily life were exhibited by 44.7% (21/47) of patients in the aprepitant triple regimen group and by 24.0% (12/50) of those in the standard regimen group (P =0.035). Three FLIE questionnaires could not be analyzed in the aprepitant regimen group because of incorrect marking. The comparison of the FLIE index of nausea and vomiting between the two groups is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of FLIE Index

| Items | Aprepitant regimen | Standard regimen | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nause FLIE Score | 46.67±13.77 | 42.01±12.12 | 0.150 |

| Vomiting FLIE Score | 53.32±12.71 | 47.34±13.31 | 0.066 |

| FLIE Score | 99.97±22.49 | 88.95±24.75 | 0.080 |

Notes: FLIF: functional living index-emesis

3.4. Comparison of time to first vomiting

Kaplan–Meier curves of time to first emesis were similar between the two groups up to 72 h, after which longer times to first emesis were observed in the aprepitant regimen group (P =0.201). The first emesis events were observed in 30.0% (15/50) and 18.0% (9/50) of patients in the standard group and aprepitant group, respectively.

3.5. Tolerability

The most common aprepitant-related AEs were fatigue and constipation which occurred in 16.0% (8/50) and 16.0% (8/50) of patients, respectively, in the aprepitant regimen group versus 8.0% (4/50) and 14.0% (7/50), respectively, in the standard regimen group (P =0.10 for both). There was no significant difference in the AEs that occurred between the two groups.

4. Discussion

Clinical guidelines from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/European Society for Medical Oncology [11], the American Society of Clinical Oncology [12], and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network have recommended antiemetic therapy for HEC(highly emetogenic chemotherapy) that includes the 3-day aprepitant regimen [13]. However, the majority of trials have investigated patients receiving their first cycle of single-day chemotherapy, and MDC is one of the most neglected areas of antiemetic research. Indeed, a 5-HT3 antagonist plus dexamethasone still routine therapy for current MDC [14]. Additionally, previous investigations into the prevention of multiple-day CINV were either retrospective or single-arm observations [14,15]. We therefore conducted a non-randomized study to evaluate the effect and safety of combined neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant therapy for the prevention of multiple-day CINV.

The primary and secondary endpoints adopted in this study were in accordance with the 052, 054 multinational randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial [4,5]. Different time cut-off points between the AP and DP are reported in multiple-day CINV clinical trials [14,15], but here we defined the AP as 0–24 h following chemotherapy. Tropisetron was chosen as a 5-HT3 inhibitor because ondansetron, tropisetron, and dolasetron exhibited similar efficacies in postoperative nausea and vomiting prevention meta-analysis [16].

The current findings are consistent with previous reports for single-day chemotherapy, demonstrating that aprepitant treatment regimens achieved better CR rates during the OP and DP following initial chemotherapy treatment [4,5,17]. Conversely, our CR rates during the AP did not show a significant improvement, which is in accordance with the report of Zhang et al. [17]. Furthermore, our CR rates during the AP differ from our previous clinical observation [18], perhaps because we included patients who received high-dose cisplatin as well as lower-dose cisplatin and anthracyclines. The aprepitant regimen group in the present study achieved a high level of overall benefit (24.0%), which was identical to that seen in the 052, 054 clinical study although significantly higher than the minimum clinical relevant difference of 10% previously reported in the Chinese population [4,5,17]. Similarly, the 80.0% CR achieved during OP was consistent with the 81.5% previously reported by Zhang et al.but higher than the 58.5% reported by the Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center [14,15].

In this study, patients in both the aprepitant regimen group and the standard group exhibited higher CR rates during the AP and OP phases than in previous phase III trials. Nevertheless, the primary endpoint reached statistical significance in our study as well as in previous trials. The smaller sample sizes of our study may explain the higher CR rate. Alternatively, it may reflect the fact that acute nausea and vomiting are alleviated more by 3-day cisplatin than single-day treatment [19]. Another reason for the difference may be variations in time cut-off points between the AP and DP; indeed, Gao et al. found that the CR declined by ~20%when the AP cut-off point changed from 24 h to 72 h [20]. Furthermore, the different 5-HT3 and DXM dosages used in our study may have affected the results compared with previous 3-day CINV prevention clinical studies. The observed superiority of aprepitant in male rather than female patients also differed from the findings of previous studies [4,5,6], and may reflect the initial imbalance between male and female patients.

Patients in the aprepitant regimen group reported a significantly higher quality of life than those receiving the standard regimen (P =0.035). This finding differed from clinical research into single-day cisplatin chemotherapy in the Chinese population [15]. It indicates that aprepitant may help achieve a greater improvement to the quality of life in a 3-day cisplatin chemotherapy model. Kaplan–Meier curves of time to first emesis until 72 h were in accordance with the secondary endpoint CR in the AP. The trend of the two curves supports 72 h as a reasonable cut-off point between the AP and DP, although we define the AP as 0–24 h after treatment in this study. We propose that standard time cut-off points should be established by testing for the excretion of the urinary serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid during 3-day cisplatin chemotherapy [21].

The aprepitant-related AE profile observed in 3-day cisplatin chemotherapy included fatigue and constipation, which are entirely consistent with other studies examining aprepitant-related AEs. Thus, aprepitant was generally well tolerated.

5. Conclusion

In summary, a combination therapy of the neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant with the traditional regimen of a 5-HT3 inhibitor and DXM improved the control of CINV and life quality associated with multiple-day cisplatin chemotherapy. Moreover, the aprepitant regimen was generally well tolerated. The improvement of uncontrolled CINV in patients receiving the combined aprepitant triple regimen remains a challenge for future research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Williams, PhD, from Liwen Bianji, Edanz Group China (www.liwenbianji.cn), for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interests.

References

- [1].Ramsden K, Laskin J, Ho C.. Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Resected Stage II Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: Evaluating the Impact of Dose Intensity and Time to Treatment. Clinical Oncology. 2015;27:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hesketh PJ.. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [J] N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2482–2494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR. et al. Nausea and emesis remain significant problems of chemotherapy despite prophylaxis with 5-hydroxytryptamine-3 antiemetics: a University of Rochester James P. Wilmot Cancer Center Community Clinical Oncology Program Study of 360 cancer patients treated in the community[J] Cancer. 2003;97(11):2880–2886. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hesketh PJ, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ. et al. The oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin-the Aprepitant Protocol 052 Study Group[J] J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(22):4112–4119. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD. et al. Addition of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America[J] Cancer. 2003;97(12):3090–3098. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Roila F, Hesketh PJ, Herrstedt J.. Prevention of chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced emesis: results of 2004 Perugia International Antiemetic Consensus Conference. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(1):20–28. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McCrea JB, Majumdar AK, Goldberg MR. et al. Effects of the neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant on the pharmacokinetics of dexamethasone and methylprednisolone[J] Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Martin AR, Pearson JD, Cai B. et al. Assessing the impact of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on patients’ daily lives: a modified version of the Functional Living Index-Emesis (FLIE) with 5-day recall[J] Support Care Cancer. 2003;11(8):522–527. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Decker GM, DeMeyer ES, Kisko DL.. Measuring the maintenance of daily life activities using the functional living index-emesis (FLIE) in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy[J] J Support Oncol. 2006;4(1):35–41. 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Martin AR, Carides AD, Pearson JD. et al. Functional relevance of antiemetic control: experience using the FLIE questionnaire in a randomized study of the NK-1 antagonist aprepitant[J] Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Herrstedt J., Roila F.. et al. Updated MASCC/ESMO Consenus Recommendations: Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting Following High Emetic Risk Chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hesketh PJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH.. Antiementics: Americian Society of Clinical Oncology Focused Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:381–386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Antiemesis NCCN Clinical Practice Guideline in Oncology. Version 1. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Longo F, Mansueto G, Lapadula V. et al. Palonosetron plus 3-day aprepitant and dexamethasone to prevent nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2011 Aug;19(8):1159–1164. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0930-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ling MZ, Song ZB, Lou GY. et al. Clinical observation of aprepitant in the prevention of nausea and vomiting induced by cisplatin chemotherapy. Chinese Clinical Oncology. 2016;21(3):247–250. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tang DH, Malone DC.. A network meta-analysis on the efficacy of serotonin type 3 receptor antagonists used in adults during the first 24 hours for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis[J] Clin Ther. 2012;34(2):282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hu ZH, Cheng Y, Zhang HY. et al. Aprepitant triple therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following high-dose cisplatin in Chinese patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial[J] Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):979–987. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Li QF, Jin GW, Wang WJ. et al. Clinical observation of neurokinin-1 antagonist preventing multiple-day chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer Res Prev Treat. 2017;44(4):290–294. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dong S, Yu SY.. A study of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting involving different dosage regimen of cisplatin. Cancer Res Prev Treat. 2013;40(9):890–893. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gao HF, Liang Y, Zhou NN. et al. Aprepitant plus palonosetron and dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving multiple-day cisplatin chemotherapy[J] Intern Med J. 2013 Jan;43(1):73–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wilder-Smith OHG. et al. Urinary serotonin metabolite excretion during cisplatin chemotherapy. Cancer. 1993;72:2239–2241. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931001)72:7<2239::aid-cncr2820720729>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]