Abstract

Background:

A palliative approach to the care of people with dementia has been advocated, albeit from an emergent evidence base. The person-centred philosophy of palliative care resonates with the often lengthy trajectory and heavy symptom burden of this terminal condition.

Aim:

To explore participants’ understanding of the concept of palliative care in the context of dementia. The participant population took an online course in dementia.

Design:

The participant population took a massive open online course on ‘Understanding Dementia’ and posted answers to the question: ‘palliative care means …’ We extracted these postings and analysed them via the dual methods of topic modelling analysis and thematic analysis.

Setting/participants:

A total of 1330 participants from three recent iterations of the Understanding Dementia Massive Open Online Course consented to their posts being used. Participants included those caring formally or informally for someone living with dementia as well as those with a general interest in dementia

Results:

Participants were found to have a general awareness of palliative care, but saw it primarily as terminal care, focused around the event of death and specialist in nature. Comfort was equated with pain management only. Respondents rarely overtly linked palliative care to dementia.

Conclusions:

A general lack of palliative care literacy, particularly with respect to dementia, was demonstrated by participants. Implications for dementia care consumers seeking palliative care and support include recognition of the likely lack of awareness of the relevance of palliative care to dementia. Future research could access online participants more directly about their understandings/experiences of the relationship between palliative care and dementia.

Keywords: Palliative care, dementia, health literacy

What is already known about the topic?

Dementia is a life-limiting condition for which a palliative approach has been suggested as a suitable care frame.

Multiple challenges to the application of palliative care to those living with dementia have been identified.

What this paper adds?

This study highlights that despite a specific interest in dementia as indicated by participants’ choice to enrol in a course specifically addressing the syndrome, participants have shown a lack of awareness of how a palliative approach might contribute to dementia care.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

Those with dementia and their families encountering palliative care services may demonstrate limited understanding of the relevance of such care and require specific support and advocacy.

Introduction

People with dementia experience a wide range of symptoms, including issues around perception, cognition and behaviour1,2 and ultimately progressing to physical deficits and associated symptoms.3,4 A palliative approach to the care of people with dementia has been widely advocated,5 albeit from a still-emergent evidence base.6 The holistic and person-centred philosophy of palliative care, promoting quality of life and applicable from early in the course of illness, is argued to fit well with the often lengthy trajectory and heavy and escalating symptom burden of this terminal condition,5 and yet, challenges to its broad uptake and implementation persist, including organisational preparedness and clinical competence,7 prognostic difficulties,8 lack of family awareness of the dementia diagnosis9 and broad lack of knowledge of dementia’s terminal nature.10 This paper addresses the palliative care understanding of a population enrolled in an open online course in dementia. Findings were analysed using the dual methods of topic modelling analysis (TMA) and thematic analysis. Implications for dementia/palliative care literacy are discussed.

Methodology

Data source – the Understanding Dementia Massive Open Online Course

In recognition of the major need for public education about the growing public health issue of dementia and out of a commitment to improving dementia literacy, the Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre (WDREC) at the University of Tasmania conceptualised and developed the Understanding Dementia Massive Open Online Course (UDMOOC) in 2012.

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) emerged as a novel online pedagogy in 201211 and have continued to develop as a learning methodology since that time in a wide range of areas, including health and medicine12,13 and addressing both dementia14,15 and palliative care.16,17 Data from MOOCs are emerging within the published literature from research exploring health pedagogy18,19 and progressively utilising the participant metadata generated to explore social and professional health knowledge and attitudes.16,20

The 9-week UDMOOC is designed to engage and inform international participants within three broad modules: ‘The Brain’ which addresses neuroanatomy, ‘The Diseases’ which explores conditions that give rise to dementia and ‘The Person’ which focuses on the care and support needs of the person. The UDMOOC has a dynamic structure designed to allow participants to ask questions, share knowledge and experience with others and seek guidance. These contributions are facilitated through various forums addressing issues, including dementia types, diagnosis, palliative care, pain and symptom management, carer support, decision-making, caregiving and meaningful activities.

In the eighth week of the UDMOOC, participants are given a brief introduction to the concept of a palliative approach (consisting of an approximately 8-min conversational video discussing the origins of palliative care, its traditional linkage to malignant disease, its contemporary expansion as an option for other chronic, life-limiting illness and its focus on quality of life rather than cure) and more substantive content on palliative care and dementia. Subsequent UDMOOC content and Thought Trees address pain and other symptom management, but that content and related activities fall outside of the context of this analysis. For this study, following the introductory video, participants are invited to contribute to a ‘Thought Tree’ forum, a device designed to enable them to share ideas with others in a relatively non-threatening space that assumes no specialist knowledge and encourages them to consider their understandings prior to further exposure to information. This ‘Thought Tree’ asks them to complete the sentence: ‘Palliative care means …’ The responses to this invitation constitute the data informing this paper.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Tasmania Social Sciences Ethics Committee (H0015065). Participants were required to provide informed consent by nominating to either ‘opt in’ or ‘opt out’ from their data usage for research purposes at enrolment. This option could be altered at any time during their participation in the online course.

Participants

Participant data for enrolees in the three most-recent iterations of the UDMOOC (2014, 2015 and 2016) were extracted, resulting in a total of 27,569 potential participants, of which 15,842 or 57.5% consented to participate in research. A total of 2082 participants posted comments in the ‘Palliative care means …’ Thought Tree. Of these, 1330 or 64% were over 18 years and consented by opting in to the inclusion of their data for research purposes (Table 1). Demographic data were extracted, together with the full content of the first post – in order to capture participants’ initial concepts with minimal influence of any subsequent discussion – in the ‘Palliative care means …’ Thought Tree for this group. To enhance understanding of the experience of dementia of this group, participants were asked to indicate whether they had provided unpaid care (e.g. for a family member or friend; Category 1), professional (paid) care (Category 2), both unpaid and professional care (Category 3) or neither unpaid nor professional care (Category 4) for people living with dementia. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of participants in any particular category (including time since being a caregiver) posting to this Thought Tree.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Category 1 | Category 2 | Category 3 | Category 4 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal (unpaid) carers | Care (paid) workers | Both personal carers and care workers | Neither personal carer nor care worker | ||

| N | 56 (4%) | 854 (64%) | 22 (2%) | 389 (29%) | 1330 |

| Male | 4 | 66 | 2 | 43 | 116 (8.7%) |

| Female | 52 | 788 | 20 | 346 | 1214 (91.3%) |

| Median age (range) | 56 (19–77) | 50 (20–76) | 54 (26–74) | 54 (18–84) | 52 (18–84) |

Analysis

TMA

Structural topic models21 were fitted by an author (A.B.) who has experience in topic modelling to explore the content that resonated with participants when asked to consider what palliative care means. This approach has been recently applied to MOOC discussion fora, as it offers a mechanism to explore large textual data sets22 and new possibilities for understanding the development of latent skills through the interrogation of discussion forum content.23

Topics were identified within participant responses to the Thought Tree by analysing the co-occurrence and exclusivity of terms within responses using the R software package ‘stm’, which is a tool to compute structural topic models.24–26 Topic models that identify the co-occurrence and exclusivity of words within documents27 provide a semantically meaningful decomposition of the concepts embodied within text.28 The primary innovation of the structural topic model is that users can include covariates in the model,24 such as metadata relating to the source of the text, and inference can be drawn on the distribution of topic prevalence by covariate. In this application, participant categories identifying their roles as non-carers, unpaid carers and/or professional carers for people with dementia (Table 1) were included in the structural topic model as a covariate.

In order to identify the participant responses most representative of each topic, the ‘findThoughts’ function of the ‘stm’ package was used. The words that were most likely to co-occur within a topic, and the words that were most exclusive to each topic, were identified using the ‘labelTopics’ function. Mean topic proportions over participant categories were estimated (with 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) using the ‘estimateEffect’ function, and differences between these categories were estimated by pairwise comparison. R code and supplementary figures for the analysis can be found at https://github.com/ABindoff/palliative_care_dementia_mooc

Secondary thematic analysis

Following Braun and Clarke,29 two authors (F.M. and K.D.) independently reviewed the representative data items extracted by the first-round TMA process in a line-by-line review of participant posts associated with structural topic model (STM)-generated topics. This second level of interrogation enabled identification of coherent and meaningful patterns and confirmed theoretical saturation, where the theme was seen as complete.30 These authors then compared their findings and found strong consensus that lead to acceptance of a 12-topic model. Review of participant posts, however, found three topics which primarily consisted of verbatim quotes copied and pasted from third-party sources, namely, the online Wikipedia and World Health Organization online definitions of palliative care, in addition to a sentence apparently derived from the UDMOOC text introducing the Thought Tree exercise; as a consequence, these topics were discarded (Table 2). Other representative data from the remaining nine topics were closely interrogated and found to be characterised by a diversity of language with no obviously derived content. In order to illustrate the themes, representative data extracts generated by the TMA were again independently located by the above two authors (F.M. and K.D.) and consensus subsequently reached. Deviant cases – instances in the data which contradicted dominant themes – were also explored as a further aid to analytic rigour,31 and some of these are identified and presented within the relevant themes below.

Table 2.

The 12-topic model generated by TMA is illustrated with themes arising from the analysis of posts associated with each topic.

| Structural topic modelling topics | Contextualised interpretation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original topic | Frequently co-occurring words | Most exclusive words | Theme identifier | Description |

| 1 | person, comfort, care, digniti, make, final, allow | allow, comfort, final, digniti, person, make, gentl | Dignity and comfort | Actions to enhance comfort, dignity and freedom from pain at the end of life |

| 2 | may, plan, will, place, death, process, long | discuss, process, benefit, short, long, carri, agre | Planning for end of life | Involves planning for end of life while person is still capable of contributing their wishes |

| 3 | provid, ill, termin, mean, someon, cure, individu | someon, highest, provid, promot, meet, rather, painfre | Quality of life | In incurable conditions that the focus becomes quality of life |

| 4 | can, care, symptom, curat, home, phase, manag | deliv, hospit, enabl, general, necessarili, phase, residenti | Care in diverse settings | Diverse places of care (gap broad symptom management). In dementia, the terminal phase is often not evident. Delivered where the person needs it |

| 5 | one, love, time, care, famili, mean, make | talk, let, music, thing, room, said, want | Social connection maintained | Family, social emphases |

| 6 | end, possibl, pain, stage, best, ensur, give | free, respect, ensur, possibl, dignifi, end, manner | Optimal care environment | Dignified, familiar, peaceful environments |

| 7 | care, patient, symptom, pain, ill, focus, relief | stress, serious, specialis, focus, reduc, allevi, discomfort | Symptom control | Verbatim quotes dominate – exclude |

| 8 | support, care, famili, also, given, last, involv | stress, serious, specialis, focus, reduc, allevi, discomfort | Family support | Family support, recognition of family as part of the palliative care provision as well as in need of support from palliative care |

| 9 | dementia, need, diseas, die, live, peopl, help | failur, amp, diseas, kidney, motor, neuron, heart | Appropriate for any life-limiting condition | Applicable to a variety of conditions other than cancer and dementia |

| 10 | life, qualiti, limit, condit, care, enhanc, manag | limit, condit, qualiti, life, enhanc, maintain, quantity | Quality of death | Promoting quality of living and dying |

| 11 | approach, symptom, reliev, care, aim, use, maximis | maximis, multi, function, disciplinari, reliev, aim, chaplain | Multidisciplinary team | Verbatim quotes dominate – exclude |

| 12 | physic, life, spiritu, emot, famili, ill, problem | problem, physic, threaten, face, spiritu, emot, assess | Holism | Verbatim quotes dominate – exclude |

TMA: topic modelling analysis.

Following TMA, posts within each topic were thematically analysed resulting in the contextualised interpretation shown here. Topics 7, 11 and 12 were excluded from further analysis due to high frequency of third-party quotes in the representative sample.

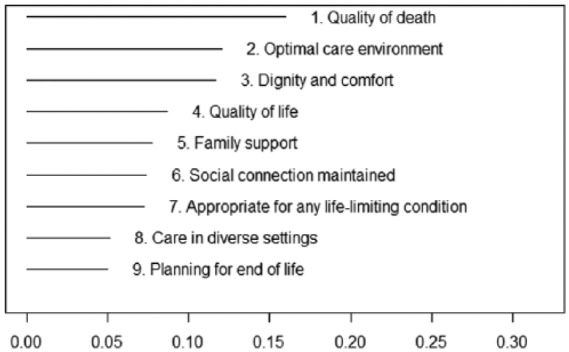

Findings

The nine topics which emerged out of the structural TMA and thematic analysis are represented by data extracts and discussed under thematic headings in the following. The themes are presented in the order determined by the topic proportions over the entire data corpus identified by the TMA process (Figure 1). Pairwise comparison using 95% (Bayesian) CIs (see Supplementary Materials at https://github.com/ABindoff/palliative_care_dementia_mooc) revealed little difference in proportional representation of the topics between participants grouped (as per Table 1) on the basis of their experience of providing dementia care to a family member at any point or in the workplace. Hence, Figure 1 considers the topics from the perspective of the whole participant cohort. While there is some overlap in the textual representations, reflective perhaps of the interrelatedness of a number of tenets of palliative care, the themes stand alone. Participants are identified by gender (F/M), age and care category (1–4 as per Table 1).

Figure 1.

The relative proportion of each of the nine topics within the whole data set was calculated. These data show, for example, a higher relative proportion of quotes centred on ‘Quality of Death’ than ‘Quality of Life’.

Quality of death

An awareness of the relationship between palliative care and mortality was clearly expressed by UDMOOC participant postings: Assisting those with life limiting diseases to experience a good quality of life and death for that matter (F, 42 years, 4). Participants predominantly used the language of ‘quality of death’ over ‘quality of dying’ in their entries, which suggests a focus on the event of death as opposed to the process of dying as well as an equating of palliative care with terminal care (an emphasis also seen later in the ‘planning for end-of-life’ theme): … providing a range of cares [sic] to someone with a life limiting condition aimed at promoting quality of life (and death), not necessarily quantity of life (F, 43 years, 2). There was the rare posting that indicated a more sophisticated understanding of the place and scope of palliative care for those with a life-limiting illness, as here: To me, palliative care means providing comfort ti [sic] any individual with a terminal illness. Although many individuals believe palliative care is only for those in late stages of diseases and close to death it is not (F, 37 years, 2).

Optimal care environment

Here, participants focused on the qualities that made a care environment optimal from within a palliative framework. There was a strong focus on maintaining a context that was familiar and peaceful: … caring for the person in order to keep them comfortable, giving them a life with dignity, hopefully in a peaceful familiar environment (F, 38 years, 2). While specific references to dementia were not evident in postings around this topic, the repeated references to ‘familiarity’ were possibly an acknowledgement of the threats to memory and orientation posed by dementia that need to be taken into consideration in care: … that the person…is able to come to the end of their life in familiar surroundings and with those that have loved and cared for them (F, 48 years, 2).

Dignity and comfort

The dual concepts of dignity and comfort were prominent in participant depictions of palliative care, with the two being closely aligned: Making sure a patient is as pain free as possible, to keep them comfortable, safe and give them dignity during the final days of their illness (F, 62 years, 1). Comfort was often spoken of in the context of being ‘pain free’, with little reference to other symptoms the person might experience, or other ways comfort might be achieved; here, an attempt to address this produces a very general aim: … where a person is treated with dignity and respect and keep him/her comfortable in every possible way (F, 25 years, 2). As in the majority of other themes, it was relatively rare that dementia itself was overtly mentioned; the following reference to ‘personhood’, a concept introduced into dementia discourse by Kitwood,32 being a likely exception: … maintaining the person’s dignity and personhood; providing comfort (freedom from pain) while doing what can be done to bring joy and happiness for the person (F, 62 years, 2).

Quality of life

As distinct from the ‘quality of death’ theme above, here, participants distinguished between curative interventions focused on maximising length of life and those designed to enhance quality of life for individuals with a life-limiting condition: … actions meant to provide a person diagnosed with a life limiting illness such as cancer or dementia (or others) with the best quality of life and to meet their needs that their condition/conditions bring up … It also includes helping a person earlier in their dementia journey with individualized responses to their presented needs (F, 60 years, 1). Quality of life was seen as more than symptom management, and to include the concepts of pleasure and activities; again, while this focus may have had a direct link to dementia, it was not made overt by respondents: providing comfort and support to someone with a life limiting illness which enables them to maintain a quality of life that they would like. Maximising their participation in activities of life that give them pleasure … (F, 48 years, 4).

Family support

The centrality of family in the context of palliative care was another clear theme in participants’ depictions of palliative care: Palliative care takes a person and family-centred approach, which means that it is up to the person as to when and where they receive palliative care, and what palliative care services they receive. It also offers families and carers emotional and practical support (F, 25 years, 4). The carer burden imposed by dementia may have been evident in this response calling for greater family support to assist them in their carer role: … when family members get assistance, they can have more energy to care for their family member (F, 54 years, 2). In a rare example, a more overt acknowledgement of the particular needs of family engaged in caring for someone with dementia was seen in the following eloquent depiction: [The] palliative care team also extend[s] to guiding family members and other loved-ones through the tangled and unstable web that dementia causes … (F, 58 years, 4).

Social connection maintained

The importance of social connectedness was identified by respondents. This theme was an area where the role of social support was explicitly identified as important to those with dementia: … show them love, kindness, with things such as putting [on] their favorite music, or reading, talk with them even if we know that they are not the same person that we knew before (F, 36 years, 2). The centrality of maintaining social links with the person with dementia and providing ongoing companionship was identified: Seeing that they have a good surrounding [sic], music they love, objects they assosiate [sic] with and were [sic] possible people who know and love them there at the end … (F, 52 years, 2). The threat dementia poses to the very humanity of affected individuals and the potential of the philosophy of palliative care to redress this were also highlighted: … treating the person/resident like a human being, laugh and cry with them, attend to their needs in a respectful way (F, 50 years, 2).

Appropriate for any life-limiting condition

Within this theme, participants explored the concept that palliative care was useful for a range of life-limiting conditions: … it is typically associated with cancer patients but is equally relative [sic] to Dementia sufferers, people suffering from chonic [sic] diseases such as heart or kidney failure or the end stages of motor neuron disease (M, 65 years, 2). One respondent embraced the broad applicability of palliative care, including ‘the elderly’, albeit suggesting old age is a disease: … for everyone with a life ending disease which to me includes all the elderly as we are all going to die sometime (F, 74 years, 2). The dominance of cancer in palliative care discourse was overtly acknowledged and critiqued by one respondent, who also identified dementia as a discrete entity for which palliative care could be used: Cancer patients have a conetation [sic] with end of life … People ‘suffer from’ and ‘fight the brave fight’ with cancer. People with dementia are not tagged with that linkage of fighting the disease. This is because a lot of the population (including health care workers) do not know that dementia is progressive and is terminal (F, 62 years, 4). Yet, another respondent noted that palliative care was not available for all who might benefit from it, including those with neurodegenerative disorders: … it would be great if in reality it was available to clients iwth [sic] other nuerodegenerative [sic] conditions, like Parkinson’s Disease, as well as other chronic progressive and life limiting conditions like COPD, CCF, etc. (F, 61 years, 2).

Care in diverse settings

Distinct from Theme 2, which depicted ideal environmental qualities for the provision of palliative care, here the diversity of care contexts within which palliative care can be encountered was acknowledged. Many respondents provided broad lists of possible palliative care environments, both within healthcare and broader social settings: Can be delivered in the community, own home, residential care, hospitals, together with other interventions (F, 54 years, 4). The specific contexts of people living with dementia were occasionally acknowledged, here by a participant referring to their workplace: In our context in dementia care, frequently delivered in the person’s own home, or in a residential setting, a nursing home type setting (F, 54 years, 4). However, the scenario where people living with dementia might receive palliative care within a hospital, hospice or palliative care unit was not obvious in the data, as respondents showed a relatively limited contextual understanding. Awareness of the broader palliative approach and its relevance to those with chronic illnesses including dementia was not explicit; rather, understandings appeared to come from a specialist model frame, with frequent reference made to palliative care contexts being: … anywhere that has the necessary specialists they [sic] can deliver quality of care for the last stage of life (F, 59 years, 4).

Planning for end of life

The value of planning ahead for later life needs was raised by participants within the broad context of the meaning of palliative care, and here a more overt link to the situation of the person living with dementia was identified: Recognising and introducing the plan for palliation before the imminent arrival of the point of death. The bravery to discuss this early in the disease process while the person with dementia can contribute to the plan for their future journey (F, 60 years, 2). The focus on ‘imminent arrival of the point of death’ was reflective of a conflation of palliative care with terminal care, encountered in Theme 1 above. While not overtly using the language of advance care planning, respondents specifically advocated for early identification of needs for the person living with dementia: It helps people not to be afraid when they can feel in control of some decisions when so much is out of control (F, 47 years, 2).

Discussion

The study cohort had an existing interest in and/or experience of dementia, indicated by their enrolling in the UDMOOC. Their responses to the ‘Thought Tree’ phrase ‘Palliative care means …’ generated nine broad themes that were consistent with much contemporary palliative care discourse. Quality of death33 and quality of life,34 an optimal environment for care,35,36 maintaining dignity37 and comfort,38 providing family support,39,40 maintaining social connectedness,41 applicability for multiple life-limiting conditions42,43 available across settings where the need is evident44 and including planning for later and end-of-life needs45 are all prominent palliative care tenets. The three additional themes omitted from the analysis – symptomatic relief, multidisciplinary team and holism – are also germane to palliative care,46 and in that respect, all identified themes are relevant to the general question of what palliative care means.

As has been identified elsewhere,47 for this cohort, palliative care was primarily and erroneously equated with terminal care. Terminal care’s focus on the last days or weeks of life has been identified as only a part of what palliative care has to offer.48,49 In addition, this understanding is particularly problematic in dementia, where individual prognostication around the onset of the terminal phase is highly uncertain50 and where early incorporation of a palliative approach has been suggested.51,52 This finding was also reflected in participants’ focus on the ‘event’ of death rather than the ‘process’ of dying.53 Dementia’s terminal trajectory may take many months even in the advanced stage, with associated symptom burden and often lack of a clear terminal phase.4 A narrow focus on ‘quality of death’ and ‘terminal care’ is thus problematic and may entail a failure to identify the palliative care needs of the person living with this condition.

While comfort was a dominant area advocated by participants, this concept was almost entirely equated with pain relief; the broad range of symptoms in addition to pain that are associated with dementia4 being overlooked. Diversity of care settings for the delivery of palliative care was likewise identified and promoted; however, the lack of awareness of palliative care provision in hospital, hospice or palliative care units for people living with dementia again illustrated a lack of contextual understanding of the palliative care needs of such individuals. The strong focus on ‘specialist’ provision, an emphasis that overlooks the generalist, ‘palliative approach’ to care that has been advocated for those with dementia,54,55 was further evidence of this gap in understanding.

Somewhat surprisingly, deep into a course specifically addressing dementia, aside from themes addressing the role of social connectedness (Theme 6), the appropriateness of palliative care for a range of life-limiting conditions (Theme 7) and early planning for end-of-life care (Theme 9), there was little overt reference by participants to the relationship of palliative care to dementia. While participants were not asked to make these direct links, it is nonetheless of interest that a cohort engaged in a substantive dementia learning context, that might reasonably be expected to make the relationship of palliative care to the life-limiting condition of dementia explicit when given a direct opportunity, overwhelmingly did not. Responses indicated overall familiarity with traditional concepts of palliative care, but with little direct exploration, translation or application of this to dementia. It is of some concern that participants with a direct interest in and subsequent exposure to dementia-related content overwhelmingly failed to make the link between dementia and palliative care when given the opportunity to do so.

The finding that paid and informal carers alike had both similar understandings and limitations in those understandings of dementia palliation highlights the need for greater education of those formally involved in care provision and support. These are the individuals from whom people living with dementia and their families are likely to seek assistance. It also highlights the need for dementia palliation literacy (involving knowledge, skills and awareness56) more broadly to be promoted at a public health and policy level. The implications of these findings for the general community, who unlike the study cohort have likely not had exposure to or interest in dementia and who may present to palliative care providers for immediate dementia-related needs, are significant. They suggest that the dementia palliation health literacy of those requiring such care and support may well be wanting. As the number of people experiencing dementia and related care needs continues to rise, these findings pose an ongoing challenge to aged, dementia and palliative care to raise awareness of and advocate for access to palliative care as indicated for those experiencing this condition. It further raises the importance of awareness raising as an important public health strategy, as well as investigating health provider curricula for content that addresses these areas of need. Future research, in addition to developing the evidence base for the role of palliative care for those experiencing dementia, might also access online participants such as those in this study more directly about their understandings/experiences of the relationship between palliative care and dementia.

Conclusion

This paper has reported on a large dementia online-learning cohort’s understandings of palliative care. Using the dual methods of TMA and thematic analysis, this study identified a general familiarity with traditional palliative care concepts, but an overarching lack of awareness of the relevance of these to the specific needs of people living with dementia. Study findings raise the issue of the need for health workers to be better informed themselves and in turn to develop the capability to inform and support those living with dementia and their carers who may benefit from palliative care into the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the data management assistance of Mr Ciarán O’Mara in the production of this manuscript. Thanks also go to the Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre’s Health Services Research Group who workshopped a version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. van der Linde R, Dening T, Stephan B, et al. Longitudinal course of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a systematic review. Brit J Psychiat 2016; 209: 366–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Metzler-Baddeley C. A review of cognitive impairments in dementia with Lewy bodies relative to Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease with dementia. Cortex 43(5): 583–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toop S, Devine M, Akporobaro A, et al. Causes of hospital admission for people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013; 14(7): 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. New Engl J Med 2009; 361(16): 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliative Med 2014; 28(3): 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goodman C, Evans C, Wilcock J, et al. End of life care for community dwelling older people with dementia: an integrated review. Int J Geriatr Psych 2010; 25(4): 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ryan T, Gardiner C, Bellamy G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the receipt of palliative care for people with dementia: the views of medical and nursing staff. Palliative Med 2012; 26(7): 879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown MA, Sampson EL, Jones L, et al. Prognostic indicators of 6-month mortality in elderly people with advanced dementia: a systematic review. Palliative Med 2013; 27(5): 389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Penders YW, Albers G, Deliens L, et al. Awareness of dementia by family carers of nursing home residents dying with dementia: a post-death study. Palliative Med 2015; 29(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Toye C, Lester L, Popescu A, et al. Dementia Knowledge Assessment Tool Version Two: development of a tool to inform preparation for care planning and delivery in families and care staff. Dementia 2014; 13(2): 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pappano L. The year of the MOOC. New York Times, 11 November 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html

- 12. Liyanagunawardena T, Williams S. Massive open online courses on health and medicine: a review. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16(8): e191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pickering J, Swinnerton B. An anatomy massive open online course as a continuing professional development tool for healthcare professionals. Med Sci Educ 2017; 27(2): 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gitlin L, Hodgson N. Online training – can it prepare an eldercare workforce. Generations 2016; 40(1): 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Robertshaw D, Cross A. Experiences of integrated care for dementia from family and carer perspectives: a framework analysis of massive open online course discussion board posts. Dementia. Epub ahead of print 1 January 2017. DOI: 10.1177/1471301217719991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rawlings D, Tieman J, Sanderson C, et al. Never say die: death euphemisms, misunderstandings and their implications for practice. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017; 23(7): 324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramchandran K, Fronk J, Passaglia J, et al. Palliative care: always as a massive open online course (MOOC) to build primary palliative care in a global audience. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(29): 123.26438117 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goldberg L, Bell E, King C, et al. Relationship between participants’ level of education and engagement in their completion of the Understanding Dementia Massive Open Online Course. BMC Med Educ 2015; 15: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehta N, Hull A, Young J, et al. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med 2013; 88(10): 1418–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Annear M, Eccleston C, McInerney F, et al. A new standard in dementia knowledge measurement: comparative validation of the dementia knowledge assessment scale and the Alzheimer’s disease knowledge scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016; 64(6): 1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Airoldi EM. A model of text for experimentation in the social sciences. J Am Stat Assoc 2016; 111(515): 988–1003. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ezen-Can A, Boyer KE, Kellogg S, et al. Unsupervised modeling for understanding MOOC discussion forums: a learning analytics approach. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Learning Analytics And Knowledge (LAK ‘15), Poughkeepsie, New York, 16–20 March 2015, pp. 146–150. New York, NY: ACM, 2015, https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2723589 [Google Scholar]

- 23. He J, Rubinstein BIP, Bailey J, et al. MOOCs meet measurement theory: a topic-modelling approach. In: 30th AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, 12–17 February 2016, AAAI; https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/HCOMP/AAAI16/index. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Tingley D. stm: R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software 2014, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/stm/vignettes/stmVignette.pdf

- 25. Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Tingley D, et al. The structural topic model and applied social science. In: Advances in neural information processing systems workshop on topic models: computation, application, and evaluation; 2013, https://scholar.princeton.edu/files/bstewart/files/stmnips2013.pdf

- 26. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016, https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blei DM. Probabilistic topic models. Commun ACM 2012; 55(4): 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chang J, Boyd-Graber J, Gerrish S, et al. Reading tea leaves: how humans interpret topic models. In: Advances in neural information processing systems 22: proceedings of the 2009 conference, 2009, https://papers.nips.cc/paper/3700-reading-tea-leaves-how-humans-interpret-topic-models.pdf

- 29. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res 2008; 8(1): 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Seale C. Ensuring rigour in qualitative research. Eur J Public Health 1997; 7(4): 379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitwood T. Concern for others: a new psychology of conscience and morality. London: Routledge, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ling J. The 2015 quality of death index: global palliative care rankings. Eur J Palliat Care 2016; 23(1): 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Catania G, Beccaro M, Costantini M, et al. What are the components of interventions focused on quality-of-life assessment in palliative care practice? A systematic review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2016; 18(4): 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Macartney JI, Broom A, Kirby E, et al. Locating care at the end of life: burden, vulnerability, and the practical accomplishment of dying. Sociol Health Ill 2016; 38(3): 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pivodic L, Pardon K, Morin L, et al. Place of death in the population dying from diseases indicative of palliative care need: a cross-national population-level study in 14 countries. J Epidemiol Commun H 2016; 70(1): 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnston B, Larkin P, Connolly M, et al. Dignity-conserving care in palliative care settings: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs 2015; 24(13–14): 1743–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van Soest-Poortvliet M, van der Steen J, de Vet H, et al. Comfort goal of care and end-of-life outcomes in dementia: a prospective study. Palliative Med 2015; 29(6): 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Del Gaudio F, Zaider TI, Brier M, et al. Challenges in providing family-centered support to families in palliative care. Palliative Med 2012; 26(8): 1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hudson P, Zordan R, Trauer T. Research priorities associated with family caregivers in palliative care: international perspectives. J Palliat Med 2011; 14(4): 397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Saracino R, Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, et al. Measuring social support in patients with advanced medical illnesses: an analysis of the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire. Palliat Support Care 2015; 13(5): 1153–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fitzsimons D, Mullan D, Wilson JS, et al. The challenge of patients’ unmet palliative care needs in the final stages of chronic illness. Palliative Med 2007; 21(4): 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gómez-Batiste X, Murray SA, Thomas K, et al. Comprehensive and integrated palliative care for people with advanced chronic conditions: an update from several European initiatives and recommendations for policy. J Pain Symptom Manag 2017; 53(3): 509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lorenz K, Lynn J, Dy S, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148: 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lovell A, Yates P. Advance care planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing its uptake 2008–2012. Palliative Med 2014; 28(8): 1026–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. WHO. Palliative care fact sheet no. 402, 2015, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs402/en/ (accessed 5 August 2017).

- 47. Addington-Hall J. Research sensitivities to palliative care patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2002; 11(3): 220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. WHO. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva: WHO, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Skilbeck JK, Payne S. End of life care: a discursive analysis of specialist palliative care nursing. J Adv Nurs 2005; 51(4): 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Arcand M. End-of-life issues in advanced dementia – part 1: goals of care, decision-making process, and family education. Can Fam Physician 2015; 61(4): 330–334 and e178–e182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hughes JC, Jolley D, Jordan A, et al. Palliative care in dementia: issues and evidence. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2007; 13(4): 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Beernaert K, Deliens L, De Vleminck A, et al. Early identification of palliative care needs by family physicians: a qualitative study of barriers and facilitators from the perspective of family physicians, community nurses, and patients. Palliative Med 2014; 28(6): 480–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lawton J. The dying process: patients experiences of palliative care. London: Routledge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Parker D, Grbich C, Brown M, et al. A palliative approach or specialist palliative care? What happens in aged care facilities for residents with a noncancer diagnosis? J Palliat Care 2005; 21(2): 80–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hines S, McCrow J, Abbey J, et al. The effectiveness and appropriateness of a palliative approach to care for people with advanced dementia: a systematic review. JBI Libr Syst Rev 2011; 9(26): 960–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med 2008; 67(12): 2072–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]