Abstract

Biliary interventions are commonplace in interventional radiology. Occasionally, an anastomotic occlusion is encountered that cannot be traversed with fluoroscopy alone. Endoscopy is a tool that should be added to the interventional radiology armamentarium. Unfortunately, most departments do not have endoscopes regularly available for use by nonendoscopists. The disposable single-use flexible LithoVue scope has the potential to provide many applications for interventional radiologists. It is relatively low cost and is easy to use with a simple setup for novice endoscopists.

Keywords: Disposable endoscopy, Interventional radiology

Introduction

Interventional radiology (IR)-operated endoscopy is not widely used for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes in the angiography suite. Nonetheless, the clinical use of endoscopy during interventional radiological procedures has been described for several decades. A recent review of percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopy [1] describes the use of a variety of endoscopic techniques for both diagnosis and management of biliary disease. Ahmed et al. describe 2 main purposes of choledochoscopy, namely, for choledocholithotripsy with stone removal and for choledochoscopic-guided biopsy of hepatobiliary lesions.

Purchase of reusable endoscopes can cost upward of $20,000 per scope with associated equipment, sterilization, processing, repairs, and other additional costs totaling $2 million or greater [2]. This makes the capital investment cost prohibitive for most IR groups. The LithoVue flexible disposable endoscope (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) offers an alternative solution for interventional radiologists to perform a simple low-profile endoscopy.

Case report

This report demonstrates a case of IR-operated endoscopy facilitating the traversal of an occlusive choledochojejunostomy stricture that could not be otherwise cannulated by fluoroscopy. The use of the endoscope in this case was not planned before the procedure, and this case demonstrates the ease of use and the remarkable benefit of using a disposable endoscope to facilitate therapy in the IR suite when traditional maneuvers are unsuccessful.

Institutional review board approval was not required for the submission of this case report. A 65-year-old man who had undergone a pylorus-sparing Whipple procedure for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm 13 weeks before IR consultation presented with a biliary obstruction. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging both demonstrated extensive fibrotic tissue surrounding the biliary-enteric anastomosis with severe upstream biliary dilation. The patient presented with 5 weeks of intermittent fevers, chills, and right upper quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell count of 8.9 (89% neutrophils), alkaline phosphatase of 503, AST/ALT of 88/137, and bilirubin of 0.7. Due to concerns for cholangitis, gastroenterology was consulted and endoscopic retrograde pancreaticocholangiography was attempted, but the ampulla could not be cannulated. IR was consulted for percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography with biliary drainage.

The patient was brought to the IR suite and general anesthesia was induced. Under fluoroscopic guidance, a 22-gauge Chiba needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) was used to access a peripheral bile duct in the right hepatic lobe. A 0.018-inch Nitrex wire (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) was passed distally into the common bile duct but would not advance through the biliary-enteric anastomosis. An Accustick set (Boston Scientific) was used to convert to a 0.035-inch system through which a 4-Fr Kumpe catheter (Cook Medical) and Glidewire (Terumo Medical, Tokyo, Japan) were placed into the distal common bile duct. A 9-Fr × 25 cm vascular sheath was placed for support. Again, despite numerous attempts, the biliary-enteric anastomosis could not be crossed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography demonstrates a tight biliary stricture at the choledochojejunal anastomosis (arrow). This could not be traversed despite exhaustive efforts with various hydrophilic and nonhydrophilic wires.

The decision was made to use the LithoVue disposable endoscope to allow direct antegrade visualization of the anastomosis and to facilitate cannulation. The 9-Fr sheath was removed over a 0.035-inch SuperStiff Amplatz guidewire (Boston Scientific). A 12-Fr peel-away sheath (Cook Medical) was placed. A second Amplatz guidewire was also placed to serve as a safety wire. A 9.5-Fr outer diameter (7.7-Fr tip) LithoVue single-use disposable flexible endoscope was placed through the sheath over one of the Amplatz guidewires to the level of the stricture. The Amplatz wire was removed from the 3.6-Fr working channel of the endoscope, and the endoscope was flexed such that a tiny pinhole ostium was easily visualized. A V18 ControlWire guidewire (Boston Scientific) was passed into the ostium through the working channel of the endoscope under direct visualization (Fig. 2). A 2.8-Fr Renegade Hi-Flo microcatheter (Boston Scientific) was then placed over the wire, also through the working channel into the ostium of the strictured anastomosis. The wire was exchanged for a double-angled gold-tip Glidewire (Terumo Medical) and together with the microcatheter, was navigated through the severely stenosed biliary-enteric anastomotic stricture into the small bowel (Fig. 3).

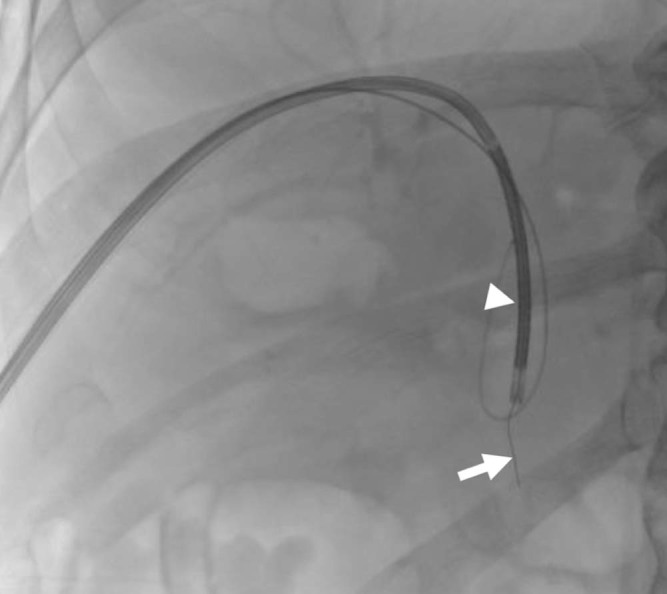

Fig. 2.

Following upsize of the sheath to accept a 9.5-Fr disposable single-use LithoVue (arrowhead) endoscope (Boston Scientific), the pinhole anastomosis is identified and cannulated with a V18 ControlWire Guidewire (arrow). Small-volume peritoneal extravasation is seen from previous fluoroscopic efforts.

Fig. 3.

Through the endoscope, the V18 ControlWire is further advanced across the anastomosis (arrowhead) into the small bowel (arrow).

The endoscope was removed and the system was upsized to a 0.035-inch system over a 4-Fr Glidecath. An Amplatz guidewire was placed through the stricture and into the small bowel. An 8 mm × 4 cm Mustang balloon (Boston Scientific) was used to dilate the stricture with moderate response. A 14-Fr internal-external Mac-Loc biliary drainage catheter (Cook Medical) was placed with the retention loop formed in the small bowel, confirmed by a small-volume iodinated contrast injection under fluoroscopy (Fig. 4). The total procedure time was 86 minutes and the fluoroscopy time was 36.1 minutes, the majority spent trying to cross the anastomosis fluoroscopically. With direct endoscopic visualization, the anastomosis was crossed in under 2 minutes. The patient's symptoms resolved within 2 days with drainage of clear bile from his catheter. The patient was discharged on postprocedure day 3 with the tube draining internally, free of a drainage bag. The patient will return for internal stenting in 6 weeks after completing a course of outpatient intravenous antibiotics.

Fig. 4.

Final image demonstrating the successful placement of a 14-Fr internal and external biliary drain.

Discussion

Interventional radiologists are experts in navigating 3-dimensional anatomy using 2-dimensional imaging guidance. However, some situations warrant the use of direct visualization. Gastroenterologists and urologists have long embraced the use of endoscopy to perform intervention. The use of endoscopy in IR has been limited both by the size of available endoscopes and prohibitive capital costs of acquisition. However, the 9.5-Fr LithoVue flexible disposable endoscope offers an affordable solution for IRs to perform endoscopy during routine procedures. The 3.6-Fr inner working channel allows the use of most guidewires, snares, and microcatheters, as well as several endoscopic tools such as Zero Tip baskets, Grasp-It baskets, and the Holmium laser (Boston Scientific). The setup is simple. There is a single cable connection point with a built-in light source to a portable, proprietary digital monitor (Boston Scientific) and a side port for infusion of pressurized normal saline to improve visualization (Fig. 5). The single-use endoscopes cost roughly $1500. With a low annual minimum usage, the parent company will provide the monitor required for operation free of charge. It is anticipated that when used appropriately, IR-operated endoscopy can generate significant cost savings through decreases in procedure time and increased efficacy of procedures, similar to findings in the urology literature [3]. Disposable single-use ureteroscopy has also been previously reported to facilitate traversal of a pyelovesicostomy stricture, which could not be traversed fluoroscopically [4].

Fig. 5.

Image demonstrating the setup for disposable single-use endoscopy using the Boston Scientific LithoVue system. The scope catheter has a 9.5-Fr outer diameter (black arrow) and tapers to a 7.7-Fr tip. It flexes up to 270° in 2 directions from a control on the rear portion of the scope. There is a single cable connection point with a built-in light source to a portable and proprietary digital monitor (white arrowhead). A 3.6-Fr working channel (white arrow) accepts a wide variety of devices including, but not limited to, wires, microcatheters, snares, laser fibers, baskets, and graspers. Pressurized normal saline is connected to the side arm of the working channel (dashed white arrow).

In this case report, had a disposable endoscope not been used, the anastomosis could not have been traversed initially, and the patient would have been left with an external biliary drain above the biliary anastomosis. This would have potentially extended the patients' hospital admission and necessitated bringing them back for a second procedure with a reattempt at crossing the obstruction, which may or may not have been successful. This would have certainly increased the costs.

Conclusion

Interventional radiologists are trained to use cutting edge technology to treat a wide variety of diseases. The learning curve for IRs to perform endoscopy is small. IR as a specialty should embrace this technology to further increase value to the health-care system.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Ahmed S., Schlachter T.R., Hong K. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;18(4):201–209. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somani B.K., Robertson A., Kata S.G. Decreasing the cost of flexible ureterorenoscopic procedures. Urology. 2011;78(3):528–530. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knudsen B., Miyaoka R., Shah K., Holden T., Turk T.M., Pedro R.N. Durability of the next-generation flexible fiberoptic ureteroscopes: a randomized prospective multi-institutional clinical trial. Urology. 2010;75(3):534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chick J.F.B., Romano N., Gemmete J.J., Srinivasa R.N. Disposable single-use ureteroscopy-guided nephroureteral stent placement in a patient with pyelovesicostomy stricture and failed prior nephroureteral stent placement. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(9):1319–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]