Abstract

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is an infectious disease caused by various species of Leishmania and transmitted by several species of sand flies. CL is among the most neglected tropical diseases, and it has represented a major health threat over the past 20 years in Morocco. The main objectives of this study were to identify relevant sand fly species and detect Leishmania infection in the most prevalent species and patient skin samples in Taza, a focus of CL in North-eastern Morocco.

Methodology and finding

A total of 3672 sand flies were collected by CDC miniature light traps. Morphological identification permitted the identification of 13 species, namely 10 Phlebotomus species and 3 Sergentomyia species. P. longicuspis was the most abundant species, comprising 64.08% of the total collected sand flies, followed by P. sergenti (20.1%) and P. perniciosus (8.45%). Using nested-kDNA PCR, seven pools of P. sergenti were positive to Leishmania tropica DNA, whereas 23 pools of P. longicuspis and 4 pools of P. perniciosus tested positive for Leishmania infantum DNA. The rates of P. longicuspis and P. perniciosus Leishmania infection were 2.51% (23/915) and 7.27% (4/55), respectively, whereas the infection prevalence of P. sergenti was 3.24%. We also extracted DNA from lesion smears of 12 patients suspected of CL, among them nine patients were positive with enzymatic digestion of ITS1 by HaeIII revealing two profiles. The most abundant profile, present in eight patients, was identical to L. infantum, whereas L. tropica was found in one patient. The results of RFLP were confirmed by sequencing of the ITS1 DNA region.

Conclusion

This is the first molecular detection of L. tropica and L. infantum in P. sergenti and P. longicuspis, respectively, in this CL focus. Infection of P. perniciosus by L. infantum was identified for the first time in Morocco. This study also underlined the predominance of L. infantum and its vector in this region, in which L. tropica has been considered the causative agent of CL for more than 20 years.

Author summary

Two types of leishmaniasis are endemic in Morocco: visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). VL is caused by Leishmania infantum, a species that is responsible for sporadic cutaneous leishmaniasis, in addition to L. major and L. tropica, which has the largest geographic distribution in Morocco. Taza province is considered as an area of mixed focus wherein VL and CL coexist. However, since the mid-1990s, this region is particularly focused upon for CL due to the presence of L. tropica. Recently, an L. infantum dermotropic variant has also been detected in CL patients. This situation calls for an in depth epidemiological investigation to identify with certainty the vectors of both L. infantum and L. tropica in this area. Our results highlight the dominance of L. infantum in cutaneous leishmaniasis patients, this species seems to invade L. tropica's field. Moreover, two phlebotomines species have been incriminated in the transmission of L. infantum, whereas the L. tropica’s vector has been confirmed. Thus, in light of our findings, the health authorities should implement control measures to counter the spread of both L. infantum and L. tropica in Taza province.

Introduction

Leishmaniasis comprises a group of diseases that are caused by various intracellular protozoa species of the genus Leishmania and transmitted by sand flies (Diptera, Phlebotominae). Leishmaniasis is responsible for considerable rates of morbidity and mortality globally, and it affects Mediterranean and other endemic countries, putting a population of 350 million people at risk of infection. The overall prevalence of leishmaniasis is estimated as 12 million cases worldwide, and the global yearly incidence of all clinical forms of the disease is 1.3 million [1] In the Mediterranean basin, two clinico-epidemiological forms of leishmaniasis are endemic: visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) [2].

VL is a zoonotic disease caused by Leishmania infantum infection. The disease tends to be relatively chronic, and children are especially affected [3]. Dogs represent the principal reservoir host in the entire Mediterranean basin [4,5]. CL is often described as a group of diseases because of the varied spectrum of clinical manifestations, which range from small cutaneous nodules to gross mucosal tissue destruction. CL can be caused by several Leishmania spp. Despite its increasing worldwide incidence, it is rarely fatal, and thus, CL has become a neglected disease.

In Morocco, CL constitutes a major health threat consisting of three nosogeographic entities: anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) caused by Leishmania tropica and transmitted by Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) sergenti [6,7]; zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) caused by Leishmania major, which has been known to exist in the vast area of the arid pre-Saharan region for over a century [8]. Phlebotomus papatasi and Meriones shawi are the vector and reservoir, respectively, of L. major [9]; and sporadic CL, which is caused by L. infantum MON-24 and is present mainly in Northern Morocco, in which ZVL caused by L. infantum MON-1 is endemic [10–12]. The phlebotomine sand fly vectors of L. infantum are considered to be Phlebotomus perniciosus, Phlebotomus longicuspis and Phlebotomus ariasi [13]. Whereas the last two species have been already reported to be infected by L. infantum [4,14], the role of P. perniciosus as a vector of L. infantum has never been confirmed in Morocco.

Recently, the epidemiological profile of leishmaniasis in Morocco has changed. Specifically, the predominance of VL in Northern Morocco and CL in Southern Morocco is no longer accurate, as the geographic distribution areas of the three medically important Leishmania species overlap. Indeed, L. tropica has been found in established L. major foci [15]. In addition, cases of VL have been reported in arid endemic areas of ZCL [16], and the dermotropic variant of L. infantum has spread to areas considered foci of CL due to the presence of L. tropica [12,17]. This is the case in Taza province, considered the first focus of CL caused by L. tropica in Northern Morocco. Indeed, in the mid-1990s, this region experienced a rapid expansion of CL due to L. tropica MON-102 [18]. Recently reported data identified L. infantum as the causative agent of CL in 41% of infected patients in this province [17]. Despite the existence of both CL and VL and co-existence of L. tropica and L. infantum in this region [17,18], data on the vectors of Leishmania transmission is not available.

Therefore, this study sought to detect and identify the Leishmania parasite responsible for the recent cases of CL and the putative vector species in Taza city, a mixed focus of CL and VL in Northern Morocco.

Materials and methods

Study region

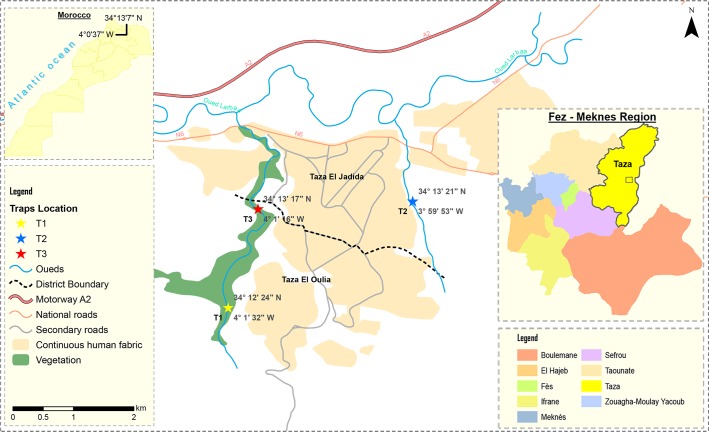

This study was conducted in peri-urban areas of Taza, situated in North-eastern Morocco in the corridor between the Rif and Middle Atlas mountains (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Map of Morocco’s Taza province showing the neighbourhoods sites in which the survey was conducted.

The map was created using ArcGIS v10 software. The base layers used to create this figure were obtained from Sentinel-2.

Taza is situation at 550-m elevation. The climate is seasonal, shifting from cool in winter to hot in summer. The temperature varies between 3.2 and 44.5°C. Although annual rainfall in the city has ranged between 84 and 120 mm over the last 8 years, the amount can reach 593 mm per year [19].

Collection and identification of sand flies

Phlebotomine sand flies were caught monthly on 3 consecutive nights between July and October 2015 in three peri-urban sites (Fig 1), using 3 CDC light traps per site placed inside houses and domestic animal shelters.

The traps were set before sunset and collected at approximately 6 am the next day. The collected sand flies were then placed in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, transferred in dry ice to our laboratory and kept frozen in −80°C for further processing and identification.

Sand fly specimens were washed in sterile distilled water, and the head and genitalia of each sand fly were removed and mounted on microscope slides using the solution of Marc-André (40 g of chloral hydrate, 30 ml glacial acetic acid and 30 ml of distilled water) for morphological identification using the Moroccan morphologic key [20,21]. The remainder of the sand fly body was stored in sterile Eppendorf microtubes for molecular use. To distinguish P. perniciosus and P. longicuspis, we used criteria based on the morphological features of their genitalia and the number of coxite hairs [22,23]. For the female subgenus Larroussius, they were separated by examining the dilatation of the distal part of spermathecal ducts [24]. In the case of males, the identification was based on the morphological features of the copulatory valve and by the number of coxite hair. P. perniciosus is characterized by two forms: (i) copulatory valves with a bifid apex; (ii) copulatory valves with a curved apex. The number of coxite hair is not higher than 18. P. longicuspis has a copulatory valve ending with a single and long point with a mild curve at the edge, and has 21 or more coxite hairs [23,25].

Human sample collection

Under the National Program of Fight against Leishmaniasis conducted in Taza by regional health authorities, we participated in active screening for 4 days in April 2015. The screening involved schools, nurseries and houses in neighbourhoods in which cases of CL were commonly reported. We also collected clinical samples from patients at health centres.

CL was suspected in 12 patients. Before sampling, we completed a questionnaire regarding information about each patient (code, age, gender, address, history of travel) and the lesions (number, location, onset of the disease, clinical characteristics).

The lesions were cleaned by Alcohol 70% and the tissue samples were collected by dermal scraping from suspected CL patients from the edge of lesions, after which slide smears were prepared, fixed with absolute methanol and stained with Giemsa for microscopic examination. The whole slides were analysed using a ×100 immersion objective.

DNA extraction from sand flies and slide smears

Total DNA was extracted from slide smears and monospecific pools of sand flies using the phenol chloroform method. Pools of unengorged females of P. longicuspis, P. perniciosus and P. sergenti were homogenised in 200 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS 1×) using a disposable pestle. After centrifugation at 6000 × g for 2 min, the supernatants were used for DNA extraction. DNA quantification was determined using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific).

Detection and identification of Leishmania species via internal transcribed spacer region (ITS1)-PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) using human clinical samples

The ITS1 was amplified using primers LITSR and L5.8S following the protocol of Schonian et al. [26]. A negative control (without DNA) was used for each PCR run. To identify Leishmania species, the positive PCR products of 350 bp in size were subjected to enzymatic restriction by HaeIII for 2 h at 37°C. RFLPs were analysed by electrophoresis on 3% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. A 100-bp DNA size marker was used (HyperLadder 100bp Plus). The restriction profiles were compared to reference strains for L. infantum (MHOM/TN/80/IPT1), L. major (MHOM/SU/73/5ASKH) and L. tropica (MHOM/SU/74/K27).

Molecular detection and identification of Leishmania species in unengorged females of P. longicuspis, P. perniciosus and P. sergenti by minicircle kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) nested PCR

The detection and identification of Leishmania parasites were performed via nested PCR amplification of kDNA as previously described [27]. Two PCR stages were performed in two separate tubes. The first-stage used the forward primer CSB2XF and reverse primer CSB1XR and the second stage used the nested forward primer 13Z with the nested reverse primer LiR. These primers allowed the amplification of the variable region of kDNA of Leishmania species, giving a specific molecular weight for each species as follows: 560 bp for L. major, 680 bp for L. infantum and 750 bp for L. tropica [27,28]. Cross-contamination was monitored using negative controls for sample DNAs and solutions of all PCR reagents used. The amplification products of nested PCR were separated and confirmed by electrophoresis in an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel.

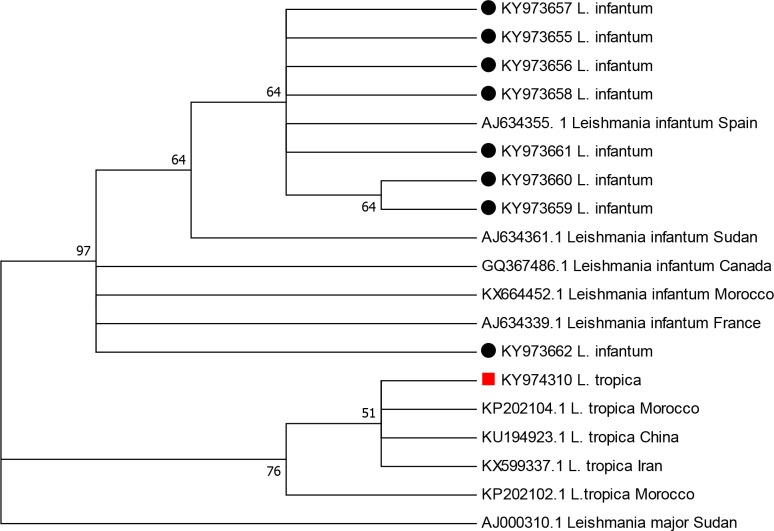

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

The obtained 350-bp ITS1-PCR products were purified using exonuclease I/shrimp alkaline phosphatase (GE Healthcare, US). The sequencing reaction was performed in both directions using BigDye Terminator version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The resulting forward and reverse sequences were aligned. A total of nine partial ITS1 DNA sequences, in addition to the studied sequences, were selected from GenBank, including five sequences from L. infantum (AJ634361, GQ367486, KX664452, AJ634339 and AJ634355), four sequences from L. tropica (KP202104, KU194923, KX599337 and KP202102) and one sequence from L. major (AJ000310). Phylogenetic analysis was performed with MEGA version 7 software using the neighbour-joining and Kimura 2-parameter models. The tree topology was supported by 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all the adults who participated in the study. Consent for inclusion of young children, was obtained from parents or guardians. The study and the protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research (CERB) of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Rabat, Morocco.

Results

Phlebotomine sand fly fauna

A total of 3,583 sand flies (2,485 females and 1,098 males, Table 1) were collected in three peri-urban neighbourhoods of Taza (Fig 1). Our results revealed a monthly evolution that varied among the species. Specifically, the evolution was monophasic for some species and biphasic for others. P. longicuspis, the most abundant sand fly species, had one peak of activity in August, whereas P. sergenti, the second most prevalent species, exhibited two peaks of activity in July and September (Table 1).

Table 1. Species diversity, abundance (A) and relative frequency (F) of sand fly collected from July to October in Taza city.

| July | August | September | October | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F | A | F | A | F | A | F | A | F | ||

| M+F | (%) | M+F | (%) | M+F | (%) | M+F | (%) | M | F | (%) | |

| P. longicuspis | 78 | 14.82 | 1355 | 77.03 | 763 | 71.37 | 158 | 85.40 | 498 | 1856 | 65.69 |

| P. sergenti | 364 | 69.20 | 151 | 8.58 | 238 | 22.26 | 10 | 5.40 | 400 | 363 | 21.29 |

| P. perniciosus* | 56 | 10.64 | 156 | 8.86 | 41 | 3.83 | 5 | 2.40 | 149 | 164 | 8.73 |

| S. minuta | 13 | 2.47 | 54 | 3.06 | 12 | 1.12 | 1 | 0.54 | 17 | 53 | 1.9 |

| P. papatasi | 9 | 1.71 | 15 | 0.85 | 6 | 0.56 | - | - | 17 | 13 | 1.95 |

| P. perfiliewi | - | - | 9 | 0.51 | 7 | 0.65 | 4 | 2.16 | - | 20 | 0.55 |

| P. bergeroti | - | - | 1 | 0.05 | - | - | 6 | 3.24 | - | 7 | 0.19 |

| P. ariasi | 1 | 0.19 | 6 | 0.34 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | 0.19 |

| P. kazeruni | 2 | 0.38 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | - | 0.05 |

| P. langeroni | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.09 | - | - | 1 | - | 0.02 |

| P. alexandri | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.09 | - | - | 1 | - | 0.02 |

| S. antennata | 3 | 0.57 | 10 | 0.56 | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | 0.36 |

| S. dreyfussi | - | - | 2 | 0.11 | - | - | 1 | 0.54 | - | 3 | 0.08 |

| Total | 589 | 100 | 1759 | 100 | 1069 | 100 | 195 | 100 | 1098 | 2485 | |

*Including typical (PN) and atypical (PNA) form of P. perniciosus

Morphological identification revealed the presence of 13 species, including 10 belonging to the genus Phlebotomus and 3 in the genus Sergentomyia (Table 1). The most prevalent species was P. longicuspis, with a relative abundance of 64.08% of the total collected sand flies. P. sergenti and P. perniciosus were the next most abundant species, comprising 20.78 and 8.52%, respectively of the specimens. These three species constituted 93.11% of the total number of collected sand flies. The remaining 3.55% consisted of P. papatasi, P. bergeroti, P. ariasi, P. dreyfussi, P. kazeruni, P. langeroni, P. alexandri, P. perfiliewi, S. minuta and S. antennata (Table 1). The sex ratio was 0.43, indicating that more females were collected by CDC light trap in this area.

Leishmania-infected flies and parasite typing by kDNA nested PCR

Unengorged female sand flies of the most prevalent species collected in this study, namely P. longicuspis, P. sergenti and P. perniciosus, were organised in a total of 54 pools, each containing up to 30 sand flies (39 P. longicuspis pools, 4 P. perniciosus pools and 11 P. sergenti pools, Table 2). The pools were screened for Leishmania infection using kDNA nested PCR. Leishmania DNA was amplified from 23 P. longicuspis and 4 P. perniciosus pools, giving a single band of 680 bp corresponding to L. infantum, as well as seven P. sergenti pools, giving an expected single band of 750 bp corresponding to L. tropica. Hence, the overall minimum L. infantum infection rates based on the positive PCR of P. longicuspis and P. perniciosus were 2.51 and 7.27%, respectively. The L. tropica infection rate within P. sergenti was evaluated as 3.24% (Table 2).

Table 2. Detection and identification of L. infantum in both P. longicuspis and P. perniciosus and L. tropica DNA in P. sergenti.

| Subgenus | Larroussius | Paraphlebotomus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | P. longicuspis | P. perniciosus | P. sergenti | ||||||

| Number of Pools | L. infantum infection | Rate of infection | Number of Pools | L. infantum infection | Rate of infection | Number of Pools | L. tropica infection | Rate of infection | |

| July | 3 | 1 | 1/44 (2.27%) | 1 | 1 | 1/12 (8.33%) | 4 | 3 | 3/76 (3.94%) |

| August | 17 | 11 | 11/394 (2.79%) | 2 | 2 | 2/28 (7.14%) | 3 | 2 | 2/59 (3.38%) |

| September | 15 | 7 | 7/397(1.76%) | 1 | 1 | 1/15 (6.66%) | 4 | 2 | 2/81 (5.26%) |

| October | 4 | 4 | 4/80 (5%) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 39 | 23 | 23/915 (2.51%) | 4 | 4 | 4/55 (7.27%) | 11 | 7 | 7/216 (3.24%) |

Leishmania-infected patients and parasite typing by ITS1-PCR-RFLP

Among the 12 patients suspected to have CL based on clinical criteria, seven were found to be positive on microscopic examination. ITS1-PCR was more sensitive, as it identified nine CL-positive patients. Enzymatic digestion by HaeIII revealed two profiles. The first consisted of two bands (185 and 57/53 bp), as observed for L. tropica (MHOM/SU/74/K27), and the second profile (184, 72 and 55 bp) was the most abundant band pattern; identical to L. infantum MHOM/FR/78/LEM75 and detected in eight patients. As for L. tropica it was observed in only one patient (Table 3).

Table 3. ITS1-PCR-RFLP results of CL patients.

| N° of patient | gender | PCR-ITS1 | RFLP-RsaI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | Positif | L. infantum |

| 2 | F | Negatif | - |

| 3 | M | Negatif | - |

| 4 | M | Positif | L.infantum |

| 5 | F | Positif | L. infantum |

| 6 | F | Positif | L. infantum |

| 7 | M | Positif | L. infantum |

| 8 | M | Negatif | - |

| 9 | F | Positif | L. infantum |

| 10 | F | Positif | L. infantum |

| 11 | F | Positif | L. tropica |

| 12 | M | Positif | L. infantum |

Leishmania DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

To confirm the PCR-RFLP identification results, the ITS1-PCR products were sequenced and subjected to NCBI-BLAST analysis for homology (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The ITS1 sequences exhibited a length range of 300–350 bp. The identity of all isolates from patients with CL was in agreement with the ITS1-PCR-RFLP results, indicating that the sequences KY973658, KY973656 and KY973661 were similar (97%) to the Spanish L. infantum sequence deposited in GenBank under accession number AJ634355, whereas KY973656, KY973657 and KY973662, were similar (98%) to the Moroccan L. infantum sequence deposited in GenBank under accession number KX664452. Conversely, the sequence KY974310 was similar to the Moroccan L. tropica sequence deposited in GenBank under accession number KP202104 (99%).

The phylogenetic analysis based on ITS1 sequences generated in this work and other sequences from NCBI revealed that all L. infantum isolates are clustered together, whereas L. tropica and L. major each appear in different clusters. The obtained tree also revealed a level of polymorphism among the L. infantum Moroccan isolates (four distinct genotypes were identified among eight isolates, Fig 2).

Fig 2. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on Leishmania ITS1 sequences showing the relationships of the sequences of L. tropica and L. infantum.

Discussion

Despite the increasing annual prevalence of leishmaniasis in Taza, little is known regarding the epidemiological aspects of VL and CL in this area. Species identification of the vectors of leishmaniasis and etiological agent typing in these vectors represent steps forward in understanding the epidemiology of leishmaniasis, which will permit the implementation of improved disease control programmes. The present study aimed to clarify the diversity and frequency of sand flies to identify the Leishmania species infecting medically important sand flies as well as patients with suspected CL. The focus of Taza is of particular importance due to the co-existence of VL and CL [17]. Whereas the visceral form is caused only by L. infantum, CL is caused by both L. infantum and L. tropica. However, there are no data on vector incrimination. The only global entomological survey focusing on the diversity and frequency of sand flies in this province was performed two decades ago. Nine sand fly species were identified, P. sergenti was the dominant species comprising 43% of the total phlebotomine species collected, following by P. longicuspis (19.5%). Throughout the study period, the activity of sand flies was marked by the dominance of P. longicuspis with one peak in August, followed by P. sergenti, which was abundant in July and declined in October. Such a pattern of seasonal abundance of P. sergenti was observed in Chichaoua, where an entomological survey was performed during July 2002 to December 2003, the peak of density of P. sergenti was reached during July and August, then the density decreased from September through November [29]. The activity period of Mediterranean adult sand flies is typically seasonal [30]. It was reported that the abundance of phlebotomine sand flies varies between species and site of collection; seasonal and monthly density patterns differ also between years, as the abundance of sand fly is impacted by the annual climate variation and local weather event [31].

In Morocco, the presence of P. longicuspis was reported in different areas, ranging from the sub-humid belt to the Sahara. The geographical distribution area of this species is characterised by an intermediate altitude, Saharan climate and sandy loam soil texture [32,33]. This species appears to have a similar distribution in Tunisia, in which it has been found in all bio-geographical areas including the Saharan bio-climatic zone, where its relative abundance reaches 60% [34].

The distribution of species belonging to the subgenus Larroussius has been widely studied [22,35]; however, little is known about their vectorial role in Morocco. P. longicuspis was considered the vector of L. infantum, as it was the only representative species of Larroussius subgenus in a ZVL focus in the arid zone in Morocco [16]. Similarly, P. longicuspis has been incriminated as a vector of L. infantum in a VL focus in Northern Morocco because it had sufficient abundance for transmitting L. infantum [4]. However, Es-sette et al. (2014) reported for the first time the natural infection of P. longicuspis by L. infantum DNA and its anthropophilic character in a CL focus in Northern Morocco [36]. In Algeria, P. longicuspis is considered a vector of L. infantum in an endemic VL focus, in which this phlebotomine species has been found to be infected by L.infantum DNA [37]. The role of P. longicuspis in L. infantum transmission was also proved by Rioux and Lanotte in a CL focus [38]. Our findings support the role of P. longicuspis in L. infantum transmission in this mixed focus in which both CL and VL are caused by L. infantum [17]. Indeed, the high abundance of P. longicuspis and its natural infection by L. infantum provide further evidence of its role as vector of L. infantum, especially considering its vector competence in L. infantum transmission has been widely demonstrated [36,39,40].

P. perniciosus is considered the principal vector of L. infantum in the Western Mediterranean basin, especially in Tunisia, Algeria, Spain and Italy [41–44]. It has also been found in all bio-geographical areas of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco [22]. This species is more common in wet floors, sub-humid areas and semi-arid high altitudes [35]. In this study, we reported for the first time the natural infection of P. perniciosus by L. infantum DNA in the country. The infection rate was estimated as 7.27% even though the abundance of P. perniciosus did not exceed 8.52% of the collected species. The infection rate varies between foci, and it is dependent on the techniques used for Leishmania detection. Indeed, in South-western Madrid, 58.5% of P. perniciosus specimens were positive for L. infantum infection using kDNA PCR methods [45], whereas in Northern and Central Tunisia, the prevalence of L. infantum infection within P. perniciosus was 0.16% according to ITS-rDNA gene nested PCR [39].

CL due to L. tropica has been identified in Taza province since 1997 [18], as well as neighbouring provinces such as Sefrou [46], Moulay Yacoub [47] and Taounate [4]. It is transmitted through P. sergenti, the proven vector of L. tropica in Morocco [6,48]. This vector was identified in Taza province in 1995, as the prevalent species, it represented 43% of the total capture, followed by P. longicuspis and P. perniciosus [18]. Twenty years later, the distribution of sand fly species is completely different; indeed, P. longicuspis is the most abundant species, comprising 64% of specimens collected in this study, followed by P. sergenti. The change in the distribution and abundance of Leishmania vectors observed in this site is suggested possibly due to long-term climate change. Indeed the global warming was reported to have strong effects on the ecology of Leishmania vectors by altering their distribution and influencing their survival and population sizes which affect the epidemiology of leishmaniasis [2,49]. Other studies in Morocco confirmed that the combined effect of climate and environmental factors (night-time temperature, soil water stress, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index and aridity) determine the vector distribution [50]. More in-depth investigation with interdisciplinary approach need to be done to explain the change of species composition by long-term climate change and to implement a more targeted approach for vector control in the region.

P. sergenti is the confirmed vector of L. tropica in North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia [6,48,51,52]. Screening for Leishmania infection within P. sergenti revealed an infection rate of 3.24% and confirmed the role of P. sergenti as the vector of L. tropica in Taza city. This infection rate may be a consequence of the important circulation of L. tropica in this focus, as the first outbreak of CL caused by L. tropica occurred in 1995 [18] and this form of CL continues to persist as reported by Hakkour et al. [17]. Moreover, our results identified one patient infected by L. tropica among people with suspected CL lesions, confirming the persistence of this Leishmania species in Taza city. Even though L. infantum is more prevalent (8 out of 9 patients were infected by L. infantum); this finding is in line with the increasing abundance of species belonging to the subgenus Larroussius.

Our results highlight three findings, including the change in the distribution of the sand fly population. Firstly, P. longicuspis has become more abundant than P. sergenti, which was more abundant during the first outbreak of CL in 1995 in this region [18]. Secondly, we identified for the first time in Morocco the natural infection of both P. longicuspis and P. perniciosus by L. infantum DNA in the same region, providing evidence that both species participate in the transmission of L. infantum in this area. Finally, we confirmed that the pattern of CL epidemiology in Taza province is about to change.

Conclusion

Based on our entomological and epidemiological findings, we believe that environmental changes may have shifted the sand fly distribution, making the subgenus Larroussius most prevalent. This has led to the establishment of a stable transmission cycle of L. infantum and subsequently to the emergence of CL due to L. infantum, which is invading the area of L.tropica. In fact, L. infantum is becoming a problem in Morocco because of its rapid spread throughout the country. Indeed, this Leishmania species was reported in several foci previously only considered L. tropica CL foci. L. infantum was also identified in L. major CL foci. Thus, more investigations and control measures are needed in Taza city in light of our findings to counter the spread of both L. infantum and L. tropica.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the team of the Department of Parasitology, DELM, Moroccan Ministry of Health. The authors are also very grateful to the local team of physicians, nurses and the Health representation of the MOH in Taza city. The authors would like to thank also Enago (www.enago.com) for the English language review.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was partially supported by CRDF Global (GTRX-14-60403-0). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

References

- 1.WHO (2017) Leishmaniasis. Fact sheet N°375: Updated April 2017.

- 2.WHO (2010) Control of Leishmaniasis Report of a meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on the Control of Leishmaniases Geneva (Switzerland). World Health Organization technical report series: 1–186.

- 3.Ministry-of-Health-Morocco (2014) État d’avancement des programmes de lutte contre les maladies parasitaires Direction de l’épidémiologie et de lutte contre les maladies, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guessous-Idrissi N, Hamdani A, Rhalem A, Riyad M, Sahibi H, et al. (1997) Epidemiology of human visceral leishmaniasis in Taounate, a northern province of Morocco. Parasite 4: 181–185. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1997042181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nejjar R, Lemrani M, Malki A, Ibrahimy S, Amarouch H, et al. (1998) Canine leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum MON-1 in northern Morocco. Parasite 5: 325–330. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1998054325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guilvard E, Rioux J-A, Gallego M, Pratlong F, Mahjour J, et al. (1991) Leishmania tropica au Maroc. III—Rôle vecteur de Phlebotomus sergenti-A propos de 89 isolats. Annales de parasitologie humaine et comparee 66: 96–99. doi: 10.1051/parasite/199166396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratlong F, Rioux JA, Dereure J, Mahjour J, Gallego M, et al. (1991) [Leishmania tropica in Morocco. IV—Intrafocal enzyme diversity]. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp 66: 100–104. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1991663100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rioux JA, Petter F, Akalay O, Lanotte G, Ouazzani A, et al. (1982) [Meriones shawi (Duvernoy, 1842) [Rodentia, Gerbillidae] a reservoir of Leishmania major, Yakimoff and Schokhor, 1914 [Kinetoplastida, Trypanosomatidae] in South Morocco (author's transl)]. C R Seances Acad Sci III 294: 515–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rioux JA, Lanotte G, Petter F, Dereure J, Akalay O, et al. (1986) Les leishmanioses cutanées du bassin Méditerranéen occidental: De l'identification enzymatique à l'analyse éco-épidémiologique. L'exemple de trois "foyers" tunisien, marocain et français. Leishmania Taxonomie et phylogenèse Application éco-épidémiologique (Coll int CNRS/INSERM, 1984) IMEEE, Montpellier: 356–395.

- 10.Lemrani M, Nejjar R, Benslimane A (1999) A new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum in northern Morocco. Giornale Italiano di Medicina Tropicale 4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamdi S, Faouzi A, Ejghal R LA, Amarouch H, Hassar M, et al. (2012) Socio-economic and environmental factors associated with Montenegro skin test positivity in an endemic area of visceral leishmaniasis in northern Morocco. Microbiology Research 3(1). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rioux JA, Mahjour J., Gallego M., Dereure J., Pe´rie`res J., Laamrani A., Riera C., Saddiki A., and Mouki B. (1996) Leishmaniose cutanée humaine à Leishmania infantum MON-24 au Maroc. Bull Soc Fr Parasitol: 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faraj C, Adlaoui EB, Ouahabi S, El Kohli M, El Rhazi M, et al. (2012) Distribution and bionomic of sand flies in five ecologically different cutaneous leishmaniasis foci in Morocco. ISRN Epidemiology 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Es-Sette N, Ajaoud M, Bichaud L, Hamdi S, Mellouki F, et al. (2014) Phlebotomus sergenti a common vector of Leishmania tropica and Toscana virus in Morocco. Journal of vector borne diseases 51: 86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kbaich MA, Mhaidi I, Ezzahidi A, Dersi N, El Hamouchi A, et al. (2017) New epidemiological pattern of cutaneous leishmaniasis in two pre-Saharan arid provinces, southern Morocco. Acta Tropica 173: 11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dereure J, Velez ID, Pratlong F, Denial M, Lardi M, et al. (1986) La leishmaniose viscérale autochtone au Maroc méridional: Présence de Leishmania infantum MON-1 chez le Chien en zone présaharienne. Leishmania Taxonomie et phylogenèse Application éco-épidémiologique (Coll int CNRS/INSERM, 1984) IMEEE, Montpellier: 421–425.

- 17.Hakkour M, Hmamouch A, El Alem MM, Rhalem A, Amarir F, et al. (2016) New epidemiological aspects of visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in Taza, Morocco. Parasit Vectors 9: 612 doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1910-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guessous-Idrissi N, Chiheb S, Hamdani A, Riyad M, Bichichi M, et al. (1997) Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an emerging epidemic focus of Leishmania tropica in north Morocco. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 91: 660–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plan MRHCd (2011) Monographie de la région Taza-Al Hoceima-Taounate.

- 20.Abonnenc E (1972) Les phlébotomes de la région éthiopienne (Diptera, Psychodidae). Cahiers de l'ORSTOM, série Entomologie médicale et Parasitologie 55: 1–239. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MMo H (2010) Lutte Contre les Leishmanioses, Guide des Activités. Direction de l’Epidé-miologie et de Lutte Contre les Maladies, Rabat, Morocco. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guernaoui S, Pesson B, Boumezzough A, Pichon G (2005) Distribution of phlebotomine sandflies, of the subgenus Larroussius, in Morocco. Medical and veterinary entomology 19: 111–115. doi: 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00548.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benabdennbi I, Pesson B, Cadi-Soussi M, Marquez FM (1999) Morphological and isoenzymatic differentiation of sympatric populations of Phlebotomus perniciosus and Phlebotomus longicuspis (Diptera: Psychodidae) in northern Morocco. Journal of medical entomology 36: 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Léger N, Pesson B, Madulo-Leblond G, Abonnenc E (1983) About the differentiation of females from Larroussius s. gen. Nitzulescu, 1931 in the Mediterranean region. Annales de Parasitologie humaine et compareé 58: 611–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boussaa S, Boumezzough A, Remy P, Glasser N, Pesson B (2008) Morphological and isoenzymatic differentiation of Phlebotomus perniciosus and Phlebotomus longicuspis (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Southern Morocco. Acta tropica 106: 184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonian G, Nasereddin A, Dinse N, Schweynoch C, Schallig HD, et al. (2003) PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 47: 349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noyes HA, Reyburn H, Bailey JW, Smith D (1998) A nested-PCR-based schizodeme method for identifying Leishmania kinetoplast minicircle classes directly from clinical samples and its application to the study of the epidemiology of Leishmania tropica in Pakistan. Journal of clinical microbiology 36: 2877–2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rassi Y, Saghafipour A, Abai MR, Oshaghi MA, Mohebali M, et al. (2013) Determination of Leishmania parasite species of cutaneous leishmaniasis using PCR method in Central County, Qom Province. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 15: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guernaoui S, Boumezzough A, Pesson B, Pichon G (2005) Entomological investigations in Chichaoua: an emerging epidemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Morocco. Journal of medical entomology 42: 697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menzel A, Sparks TH, Estrella N, Koch E, Aasa A, et al. (2006) European phenological response to climate change matches the warming pattern. Global change biology 12: 1969–1976. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alten B, Maia C, Afonso MO, Campino L, Jiménez M, et al. (2016) Seasonal dynamics of phlebotomine sand fly species proven vectors of Mediterranean leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 10: e0004458 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rioux JA RP, Lanotte G, Lepart J (1984) Phlebotomus bioclimates relations ecology of leishmaniasis epidemiological corollaries: The example of Morocco. Botanical News 131: 549–557. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahime K, Boussaa S, El Mzabi A, Boumezzough A (2015) Spatial relations among environmental factors and phlebotomine sand fly populations (Diptera: Psychodidae) in central and southern Morocco. Journal of Vector Ecology 40: 342–354. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhioua E, Kaabi B, Chelbi I (2007) Entomological investigations following the spread of visceral leishmaniasis in Tunisia. Journal of Vector Ecology 32: 371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahime K, Boussaa S, Ouanaimi F, Boumezzough A (2015) Species composition of phlebotomine sand fly fauna in an area with sporadic cases of Leishmania infantum human visceral leishmaniasis, Morocco. Acta tropica 148: 58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Es-Sette N, Ajaoud M, Laamrani-Idrissi A, Mellouki F, Lemrani M (2014) Molecular detection and identification of Leishmania infection in naturally infected sand flies in a focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northern Morocco. Parasit Vectors 7: 305 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harrat Z, Belkaid M (2003) Les leishmanioses dans l’Algérois. Données épidémiologiques. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 96: 212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rioux J, Lanotte G (1990) Leishmania infantum as a cause of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barhoumi W, Fares W, Cherni S, Derbali M, Dachraoui K, et al. (2016) Changes of sand fly populations and Leishmania infantum infection rates in an irrigated village located in arid Central Tunisia. International journal of environmental research and public health 13: 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berdjane-Brouk Z, Charrel RN, Hamrioui B, Izri A (2012) First detection of Leishmania infantum DNA in Phlebotomus longicuspis Nitzulescu, 1930 from visceral leishmaniasis endemic focus in Algeria. Parasitology research 111: 419–422. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2858-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ben Ismail R (1993) Incrimination de Phlebotomus perniciosus comme vecteur de Leishmania infantum. Arch Institut Pasteur Tunis 70: 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Izri M, Belazzoug S, Boudjebla Y, Dereure J, Pratlong S, et al. (1990) Leishmania infantum MON-1 isolé de Phlebotomus perniciosus, en Kabylie (Algérie). Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et comparée 65: 150–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maroli M, Gramiccia M, Gradoni L, Troiani M, Ascione R (1994) Natural infection of Phlebotomus perniciosus with MON 72 zymodeme of Leishmania infantum in the Campania region of Italy. Acta Tropica 57: 333–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muñoz C, Risueño J, Yilmaz A, Pérez‐Cutillas P, Goyena E, et al. (2017) Investigations of Phlebotomus perniciosus sand flies in rural Spain reveal strongly aggregated and gender‐specific spatial distributions and advocate use of light‐attraction traps. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiménez M, González E, Iriso A, Marco E, Alegret A, et al. (2013) Detection of Leishmania infantum and identification of blood meals in Phlebotomus perniciosus from a focus of human leishmaniasis in Madrid, Spain. Parasitology research 112: 2453–2459. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asmae H, Fatima A, Hajiba F, Mbarek K, Khadija B, et al. (2014) Coexistence of Leishmania tropica and Leishmania infantum in Sefrou province, Morocco. Acta tropica 130: 94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rhajaoui M, Fellah H, Pratlong F, Dedet J, Lyagoubi M (2004) Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania tropica MON-102 in a new Moroccan focus. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 98: 299–301. doi: 10.1016/S0035-9203(03)00071-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ajaoud M, Es-sette N, Hamdi S, El-Idrissi AL, Riyad M, et al. (2013) Detection and molecular typing of Leishmania tropica from Phlebotomus sergenti and lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis in an emerging focus of Morocco. Parasit Vectors 6: 217 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischer D, Moeller P, Thomas SM, Naucke TJ, Beierkuhnlein C (2011) Combining climatic projections and dispersal ability: a method for estimating the responses of sandfly vector species to climate change. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 5: e1407 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boussaa S, Kahime K, Samy AM, Salem AB, Boumezzough A (2016) Species composition of sand flies and bionomics of Phlebotomus papatasi and P. sergenti (Diptera: Psychodidae) in cutaneous leishmaniasis endemic foci, Morocco. Parasites & vectors 9: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Zahrani M, Peters W, Evans D, Chin C, Smith V, et al. (1988) Phlebotomus sergenti, a vector of Leishmania tropica in Saudi Arabia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 82: 416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Demir S, Karakuş M (2015) Natural Leishmania infection of Phlebotomus sergenti (Diptera: Phlebotominae) in an endemic focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Şanlıurfa, Turkey. Acta tropica 149: 45–48. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.