Abstract

Astaxanthin is a red-colored carotenoid, used as food and feed additive. Astaxanthin is mainly produced by chemical synthesis, however, the process is expensive and synthetic astaxanthin is not approved for human consumption. In this study, we engineered the oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for de novo production of astaxanthin by fermentation.

First, we screened 12 different Y. lipolytica isolates for β-carotene production by introducing two genes for β-carotene biosynthesis: bi-functional phytoene synthase/lycopene cyclase (crtYB) and phytoene desaturase (crtI) from the red yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. The best strain produced 31.1 ± 0.5 mg/L β-carotene. Next, we optimized the activities of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMG1) and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (GGS1/crtE) in the best producing strain and obtained 453.9 ± 20.2 mg/L β-carotene. Additional downregulation of the competing squalene synthase SQS1 increased the β-carotene titer to 797.1 ± 57.2 mg/L. Then we introduced β-carotene ketolase (crtW) from Paracoccus sp. N81106 and hydroxylase (crtZ) from Pantoea ananatis to convert β-carotene into astaxanthin. The constructed strain accumulated 10.4 ± 0.5 mg/L of astaxanthin but also accumulated astaxanthin biosynthesis intermediates, 5.7 ± 0.5 mg/L canthaxanthin, and 35.3 ± 1.8 mg/L echinenone. Finally, we optimized the copy numbers of crtZ and crtW to obtain 3.5 mg/g DCW (54.6 mg/L) of astaxanthin in a microtiter plate cultivation.

Our study for the first time reports engineering of Y. lipolytica for the production of astaxanthin. The high astaxanthin content and titer obtained even in a small-scale cultivation demonstrates a strong potential for Y. lipolytica-based fermentation process for astaxanthin production.

Keywords: Astaxanthin, β-carotene, Isoprenoids, Oleaginous yeast, Yarrowia lipolytica, Metabolic engineering

1. Introduction

Astaxanthin is a red-colored carotenoid with a global annual market of 250 tonnes worth $447 million [1]. Astaxanthin is used to improve the color of farmed fish, to increase the pigmentation of egg yolks, and for other feed applications. There is also a growing interest in using astaxanthin in food and cosmetics due to its powerful antioxidant activity [2]. The main source of astaxanthin is currently the chemical synthesis from petrochemical sources. The disadvantages of the chemical process are the high cost of the precursors, side reactions, and the fact that chemical astaxanthin is not approved for human consumption due to the presence of by-products. Several biotechnological processes have been developed, but remain too expensive to compete with chemical synthesis. A biological process based on the microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis is challenged with low cell densities, even though H. pluvialis produces the highest level of astaxanthin (1.5–3.0% dry weight) compared to other astaxanthin producers [1]. Another process, employing the native red yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous [3], [4], suffers from the low cellular content of astaxanthin. Multiple studies on the engineering of the red yeast in order to improve astaxanthin accumulation have been published. Breitenbach et al. overexpressed geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) synthase, resulting in an 8-fold increase of astaxanthin content and reaching 0.45 mg/g dry cell weight (DCW) [5]. In more recent studies, a combination of mutagenesis and metabolic pathway engineering resulted in X. dendrorhous astaxanthin content of up to 9–9.7 mg/g DCW [6], [7]. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has also been engineered for astaxanthin production by expression of genes encoding astaxanthin synthase (crtS) and cytochrome P450 reductase (crtR) from X. dendrorhous or by expression of β-carotene ketolase (crtW) from bacteria Paracoccus sp. and β-carotene hydrolase (crtZ) from Pantoea ananatis [8]. The transformants that co-expressed crtW and crtZ accumulated more astaxanthin (0.03 mg/g DCW) than the strain co-expressing crtS and crtR.

In this study, we aimed to engineer oleaginous yeast Y. lipolytica for high-level production of astaxanthin. This yeast species is an attractive host for the production of carotenoids because of its naturally high supply of carotenoids precursor, cytosolic acetyl-CoA, and redox co-factor NADPH [9], [10], [11], [12]. Y. lipolytica has a GRAS status and is genetically more accessible than X. dendrorhous [13].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains, culture conditions and chemicals

Escherichia coli DH5α was used for DNA manipulation in this study. E. coli was grown at 37 °C and 300 rpm in Lysogeny Broth (LB) liquid medium and at 37 °C on LB solid medium plates supplemented with 20 g/L agar. Ampicillin was supplemented when required at a concentration of 100 mg/L.

Y. lipolytica strain GB20 (mus51Δ, nugm-Htg2, ndh2i, lys11−, leu2−, ura3−, MatB) was obtained from Volker Zickermann (Goethe University Medical School, Institute of Biochemistry II, Germany). Other strains were obtained from ARS Culture Collection (NRRL) collection. All strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Y. lipolytica was grown at 30 °C on yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) or synthetic complete (SC) media supplemented with 20 g/L agar for preparation of solid media. Synthetic drop out media was used for selection of strains expressing auxotrophic markers. Supplementation of antibiotics was done when necessary at the following concentrations: hygromycin B at 50 mg/L and nourseothricin at 250 mg/L. Cultivation of recombinant strains for carotenoids production was performed in yeast extract peptone medium containing 80 g/L glucose instead of 20 g/L glucose (YP+8% glucose). The chemicals were obtained, if not indicated otherwise, from Sigma-Aldrich. Nourseothricin was purchased from Jena Bioscience GmbH (Germany).

2.2. Plasmid construction

The genes encoding phytoene synthase/lycopene cyclase (crtYB), phytoene desaturase (crtI) and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (crtE) from X. dendrorhous were obtained from Addgene [14]. Genes encoding X. dendrorhous astaxanthin synthase crtS (GenBank accession number AX034665) and cytochrome P450 reductase crtR (GeneBank accession number EU884134), Paracoccus sp. N81106 β-carotene ketolase crtW (GenBank accession number AB206672) and P. ananatis β-carotene hydrolase crtZ (GenBank accession number D90087) were codon-optimized for Y. lipolytica and synthesized as GeneArt String DNA fragments by Thermo Fisher Scientific.

The plasmids, BioBricks, and primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3, 4, and 5, respectively. BioBricks were amplified by PCR using Phusion U polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) under the following conditions: 98 °C for 30 s; 6 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 51 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 30 s/kb; 26 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 58 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 30 s/kb, and 72 °C for 5 min. BioBricks were purified from agarose gels using the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (Macherey-Nagel). BioBricks were assembled by into EasyCloneYALI vectors using USER cloning [15].

BioBricks were incubated in CutSmart® buffer (New England Biolabs) with USER enzyme and the parental vector for 25 min at 37 °C, followed by 10 min at 25 °C, 10 min at 20 °C and 10 min at 15 °C. Prior to the USER reaction, the parental vectors were digested with FastDigest AsiSI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and nicked with Nb. BsmI (New England Biolabs). The USER reactions were transformed into chemically competent E. coli DH5α. Correct assembly was verified by sequencing.

2.3. Construction of Y. lipolytica strains

The yeast vectors were integrated into different previously characterized intergenic loci in Y. lipolytica genome as described in Holkenbrink et al. [15]. Prior to the transformation, the integrative vectors were linearized with FastDigest NotI (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The digestion reaction was transformed into Y. lipolytica using a lithium-acetate protocol [16]. Transformants were selected on YPD + Hygromycin/Nourseothricin or SC (-ura) plates. Transformants carrying the correct integration of the DNA construct into the Y. lipolytica genome were verified by colony PCR. Marker loop-out was performed by transformation of the strains with a Cre-recombinase episomal vector pCfB4158. Obtained colonies were cultivated in liquid SC (-leu) medium for 24 h for induction of the Cre recombinase and plated on SC (-leu) plates to obtain single colonies.

The strains with downregulated squalene synthase were constructed by transformation of β-carotene producing strains with BioBricks as detailed in Supplementary Table 4. Obtained colonies were selected on SC (-ura) plates and the correct transformants were confirmed by colony PCR using primers listed in Supplementary Table 5.

2.4. Cultivation of Y. lipolytica

For pre-culture preparation, single colonies were inoculated from fresh plates in 3 mL YPD in 24-well plates with air-penetrable lid (EnzyScreen, NL) and grown for 18 h at 30 °C and 300 rpm agitation at 5 cm orbit cast.

The required volume of the inoculum was transferred to 3 mL YP+8% glucose for an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 into new 24-well plates. The plates were incubated for 72 h at 30 °C with 300 rpm agitation.

To screen the astaxanthin producing strains, generated by integration of astaxanthin genes into rDNA loci, we picked 10 clones for each transformation and streaked them on SC (-ura) plates. The resulting single colonies were inoculated into 500 μL of YPD in 96 deep-well plates with air-penetrable lid (EnzyScreen, NL). The plates were incubated for 18 h at 30 °C with 300 rpm agitation. 30 μL of this culture were used to inoculate three wells with 500 μL YP+8% glucose in a new 96 deep-well plate. The plates were incubated at 30 °C and 300 rpm for 72 h. After cultivation, 400 μL of the cultivation volume was transferred into a 2 mL microtube (Sarstedt) for carotenoids extraction and quantification as described further.

2.5. Isoprenoid extraction and sample preparation

After cultivation, OD600 was measured using either a Synergy™ Mx Monochromator-Based Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek) or NanoPhotometer (Implen GmbH, Germany). The dry-weight of a sample was measured by taking 1 or 2 mL of fermentation broth and filtering through pre-weighted cellulose nitrate membranes (0.45 μm pore size, 47 mm circle) using a filtration unit with a vacuum pump. Filters were dried at 60 °C for 96 h and weighed on an analytical balance. The conversion of OD600 values into dry cell weight was done using the following empirical correlation:

| DCW (g/L) = (OD600 − 0.026)/6.781 |

2.5.1. Carotenoids extraction

At the end of cultivation, 1 mL of the cultivation broth was transferred into a 2 mL microtube (Sarstedt) for carotenoids extraction. Each sample was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min and the supernatant removed. To each tube, 500 μL of 0.5–0.75 mm glass beads were added. 1 mL of ethyl acetate supplemented with 0.01% 3,5-di-tert-4-butylhydroxy toluene (BHT) was also added to each tube. BHT was supplemented to prevent carotenoid oxidation.

Cells were disrupted using a Precellys®24 homogenizer (Bertin Corp.) in four cycles of 5500 rpm for 20 s. After disruption, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g. For total carotenoid measurement, the solvent fraction was moved to a 96-well plate and read in BioTek Synergy™ Mx microplate reader with full spectrum scan (230 nm–700 nm) with 5 nm interval. Absorbance value at 450 nm was used to quantify total carotenoids. For the measurements of individual carotenoids, the samples were further processed before HPLC analysis as below.

2.5.2. Carotenoids quantification by HPLC

For HPLC measurements, 50–200 μL of ethyl acetate extract was evaporated in a rotatory evaporator and dry extracts were re-dissolved in 1 mL 99% ethanol +0.01% BHT. Extracts were then analyzed by HPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) equipped with a Discovery HS F5 150 mm × 2.1 mm column (particle size 3 mm). The column oven temperature was set at 30 °C. All organic solvents were HPLC grade (Sigma Aldrich). The flow rate was set at 0.7 mL/min with an initial solvent composition of 10 mM ammonium formate (pH = 3, adjusted with formic acid) (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B) (3:1) until min 2.0. Solvent composition was then changed following a linear gradient until % A = 10.0 and % B = 90.0 at 4.0 min. This solvent composition was kept until 10.5 min when the solvent was returned to initial conditions and the column was re-equilibrated until 13.5 min. The injection volume was 10 μL. Peaks were identified by comparison to the prepared standards and integration of the peak areas was used to quantify carotenoids from obtained standard curves. β-carotene and echinenone were detected at retention times 7.6 min and 6.9 min, respectively, by measuring absorbance at 450 nm. Astaxanthin and canthaxanthin were detected by absorbance at 475 nm and retention times of 5.9 min and, 6.4 min respectively.

2.5.3. Squalene extraction and quantification

After cultivation, 1 mL of the cultivation was transferred into a 2 mL microtube. Tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL 99% ethanol supplemented with 0.01% BHT. 500 μL of 0.5–0.75 mm glass beads were added to each of the tubes and tubes were incubated at 95 °C and 650 rpm for 60 min. After incubation, cells were disrupted using a Precellys®24 homogenizer in four cycles of 5500 rpm for 20 s. After disruption, the cells were centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 × g and the supernatant was collected for future analysis.

The extracts were analyzed by HPLC. HPLC column, conditions, and solvents were as described in β-carotene quantification. Squalene was detected by absorbance at 210 nm with a retention time of 6.9 min. Peaks were identified by comparison to the prepared standards and the quantification was performed using squalene standard curve generated in the same HPLC run.

3. Results

3.1. Exploring the diversity of Y. lipolytica strains for the production of carotenoids

Fourteen different Y. lipolytica strains isolated from different sources were selected as potential hosts for production of β-carotene. We successfully integrated the β-carotene biosynthesis genes into 12 of the 14 strains. The total carotenoids were extracted from these strains and quantified by spectrophotometry. The carotenoid titer varied from 5.7 to 31 mg/L total carotenoids with the highest production in the strain ST5204 derived from GB20 (Supplementary Fig. 1). This strain was chosen for further engineering.

3.2. Optimization of mevalonate pathway

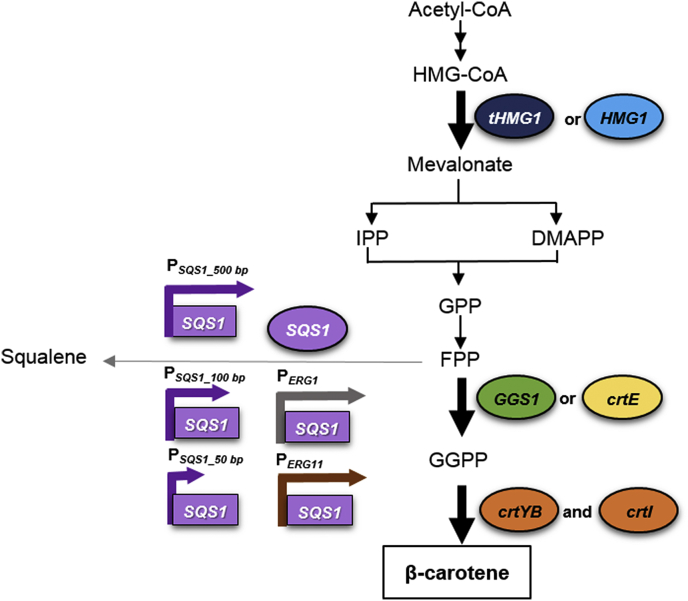

High-level production of isoprenoids in S. cerevisiae required extensive engineering of the mevalonate pathway [17]. Two steps that exert high flux control in the mevalonate pathway are 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl–coenzyme A reductase (encoded by HMG1) and geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase (encoded by crtE or GGS1 depending on the organism) (Fig. 1). Both crtE heterologous expression and GGS1 overexpression have been shown as effective strategies to enhance β-carotene production in different organisms [11], [14]. HMG-CoA reductase is a rate-limiting step in the mevalonate pathway and subjected to a strong regulation. Truncation of the N-terminal region, which contains the membrane-spanning domain (i.e. amino acid 1-552), and leaving only the catalytic domain resulted in deregulation of HMG-CoA reductase activity in S. cerevisiae [18]. In S. cerevisiae, overexpression of the truncated gene variant (tHMG1) gave a significant improvement in sterol and isoprenoids production [14], [17], [18]. For example, Verwaal et al. reported 7-fold increase in total carotenoids level producing cells [14]. The beneficial effect of HMG1 overexpression on the production of lycopene and other isoprenoids in Y. lipolytica has also been reported [11], [19]. The performance of the truncated variant Hmg1p has not previously been compared to the performance of the full-length Hmg1p in Y. lipolytica. To implement this engineering strategy in Y. lipolytica, we performed multiple alignment between Hmg1p from Y. lipolytica (YALI0E04807), S. cerevisiae (YML075C) and Candida utilis (GeneBank accession number BAA31937.1). The protein structure of Hmg1p is highly conserved among eukaryotes, of which the first 500 amino acids harbor a membrane associated N-terminal domain. Thus, we generated a truncated Hmg1p by deleting the first 500 amino acids.

Fig. 1.

Strategies for optimization of β-carotene production in Y. lipolytica. The engineered steps are highlighted. Abbreviations: DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; IPP, isopenthenyl pyrophosphate; GPP, geranyl pyrophosphate, FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate, GGPP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; HMG1 and tHMG1, full-length and truncated alleles of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase from Y. lipolytica, respectively; crtE and GGS1, GGPP synthase-encoding genes from X. dendrorhous and Y. lipolytica, respectively; crtYB, phytoene synthase and lycopene cyclase genes from X. dendrorhous; crtI, phytoene desaturase-encoding gene from X. dendrorhous; SQS1, squalene synthase gene from Y. lipolytica; PERG1, squalene epoxidase promoter; PERG11, Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase promoter; PSQS1, squalene synthase promoter.

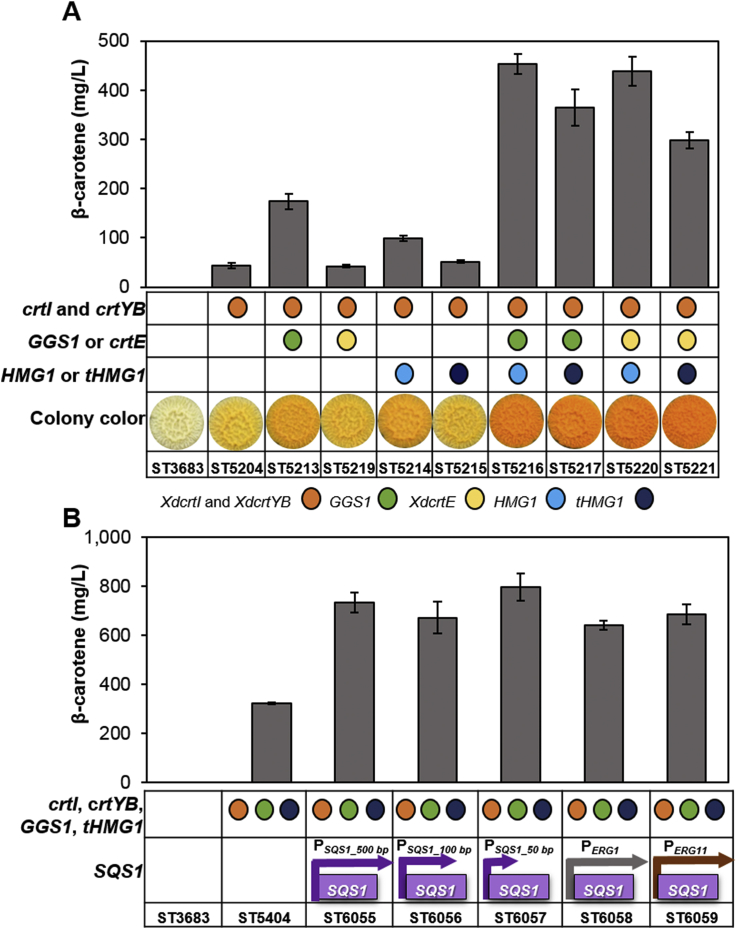

We chose to test the effect of overexpressing a complete or truncated HMG1 variant together with the expression of GGS1 or crtE from X. dendrorhous separately and in combinations. The basic β-carotene producing strain (ST5204) was used in all cases as a parental strain. All the gene expression cassettes were stably integrated into the Y. lipolytica genome and the β-carotene concentrations were measured by HPLC (Fig. 2A). Among the strains overexpressing one of the above-mentioned genes, the largest effect was obtained for GGS1 overexpression (4-fold increase in β-carotene titer). The overexpression of gene combinations resulted in further improvement, overexpression of HMG1 together with either crtE or GGS1 produced 438.4 ± 29.5 or 453.9 ± 20.2 mg/L β-carotene, respectively (10–10.3-fold increase) [though these combinations are not significantly different from each other, Student's t-test p = 0.5].

Fig. 2.

Production of β-carotene in engineered Y. lipolytica strains. A. The effect of HMG-CoA reductase and GGPP synthase overexpression on β-carotene production. B. The effect of downregulation of squalene synthase on β-carotene production. All strains were cultivated in YP+8%glucose in 24-deep-well plates for 72 h. The error bars represent standard deviations calculated from triplicate experiments.

3.3. Downregulation of the native squalene synthase increases β-carotene production

FPP is a common precursor in the mevalonate pathway including squalene, ubiquinones, ergosterol, other essential sterols, and GGPP, a substrate for β-carotene. In order to increase the availability of FPP for carotenoid biosynthesis, we downregulated the flux towards squalene in one of the β-carotene overproducing strains (ST5404). We either truncated the native promoter of the squalene synthase (SQS1) to 500, 100 or 50 base pairs or replaced it with two alternative Y. lipolytica promoters, PERG1 or PERG11. PERG1 or PERG11 promoters were chosen based on Yuan et al. (2015) study in S. cerevisiae, where they found that a number of the genes from ergosterol biosynthesis pathway were repressed by ergosterol [20]. In our study, the resulting strains gave a 2–2.5 fold increase in β-carotene titer compared to the reference strain with the native SQS1 promoter (Fig. 2B). The shortening of the promoter to 50 bp resulted in the highest β-carotene titer of 797.1 ± 57.2 mg/L. Squalene accumulation in the engineered strains was surprisingly higher than in the parental strain, with the exception of the strain with promoter truncation to 50 bp (Supplementary Fig. 2).

3.4. Establishing the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway in Y. lipolytica

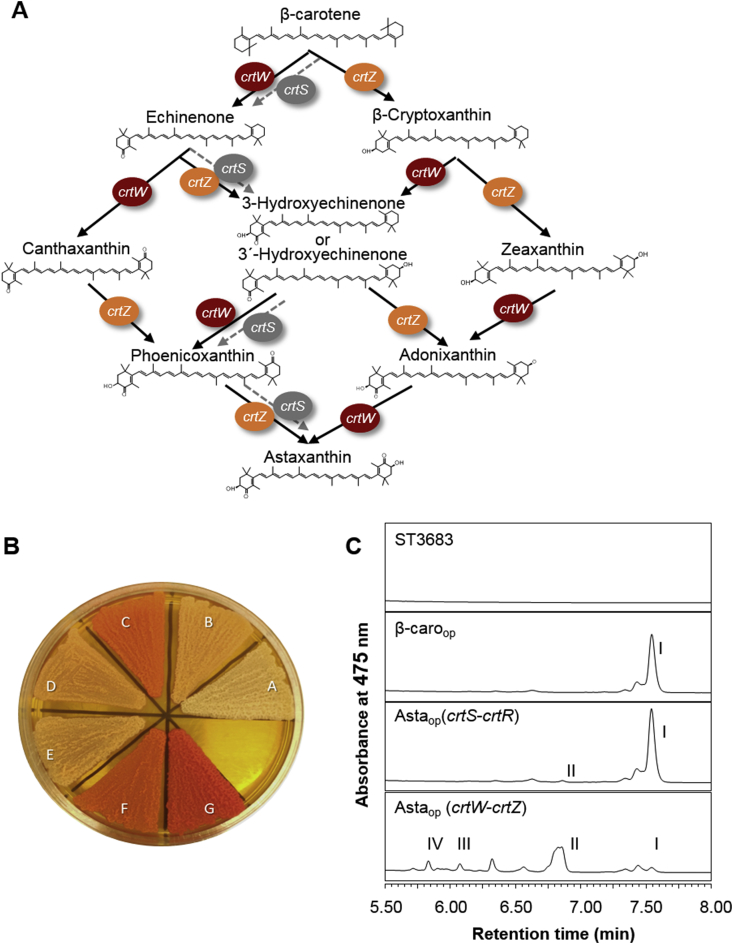

After optimizing β-carotene production in Y. lipolytica, we evaluated two different biosynthetic pathways for production of astaxanthin. The conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin requires two oxidation steps, which can be catalyzed by different enzymes (Fig. 3A). Here, we tested the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway from the red yeast X. dendrorhous (encoded by crtS and crtR), and a pathway composed of two bacterial genes (encoded by crtW and crtZ).

Fig. 3.

Astaxanthin production in Y. lipolytica. A. Astaxanthin biosynthesis pathways. The black thick arrow indicates the reactions catalyzed by the CrtW and CrtZ enzymes. The gray dashed arrow indicates the reaction catalyzed by the CrtS enzyme. To obtain a functional expression of crtS, crtR must be co-expressed. B. Engineered strains cultivated on YPD agar plates for 72 h. Strain abbreviations: (A) ST3683, Wild type; (B) ST5204, β-carotene-producing non-optimized strain; (C) ST6899, β-carotene-producing optimized strain; (D) ST6074, built by expressing crtS and crtR in ST5204; (E) ST6075, built by expressing crtW and crtZ in ST5204; (F) ST7022, built by expressing crtS and crtR in ST6899; and (G) ST7023, built by expressing crtW and crtZ in ST6899. C. HPLC analysis of carotenoids. ST3683, wild type; β-caroop, β-carotene producer with precursor optimization [ST6899]; Astaop (crtS-crtR), astaxanthin producer carrying crtS and crtR (precursor optimized) [ST7022]; Astaop (crtW-crtZ), astaxanthin producer carrying crtW and crtZ (precursor optimized) [ST7023]; Ι, β-carotene; II, echinenone; III, canthaxanthin; IV, astaxanthin. All strains were cultivated in YP+8%glucose in 24-deep-well plates for 72 h.

In X. dendrorhous, the astaxanthin synthase crtS is responsible for the conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin while crtR encodes a cytochrome P450 reductase providing electrons to crtS [21]. We introduced a crtS and crtR expression cassette into two different β-carotene platform strains, a non-optimized (ST5204) and precursor-optimized strain (ST6899). No significant change in colony color was observed in the either of the two resulting strains (Fig. 3B). HPLC analysis detected small amounts of echinenone, an astaxanthin intermediate, in the precursor-optimized strain. This strain also produced a similar β-carotene titer relative to the parental strain, but no astaxanthin could be detected (Fig. 3C).

The designed bacterial astaxanthin biosynthesis pathway was composed of a β-carotene ketolase from the marine bacterium Paracoccus sp. N81106 (crtW) and a β-carotene hydroxylase from enterobacteriaceae P. ananatis (crtZ). We again expressed both genes in a non-optimized and in precursor-optimized strains, leading to strains ST6075 and ST7023, respectively. In this case, both enzymes are directly catalyzing the oxidation reaction of β-carotene to astaxanthin. HPLC analysis detected approximately 1.4 ± 0.2 mg/L and 10.4 ± 0.5 mg/L astaxanthin in the engineered strains without and with precursor optimization, respectively (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, accumulations of approximately 3.3 ± 0.1 mg/L and 35.3 ± 1.8 mg/L echinenone were observed in ST6075 and ST7023, respectively. Canthaxanthin could also be detected, though in lower amounts, ∼0.2 ± 0.01 mg/L and 5.7 ± 0.5 mg/L in ST6075 and ST7023, respectively. The colonies of strain ST7023 had a district red color (Fig. 3B).

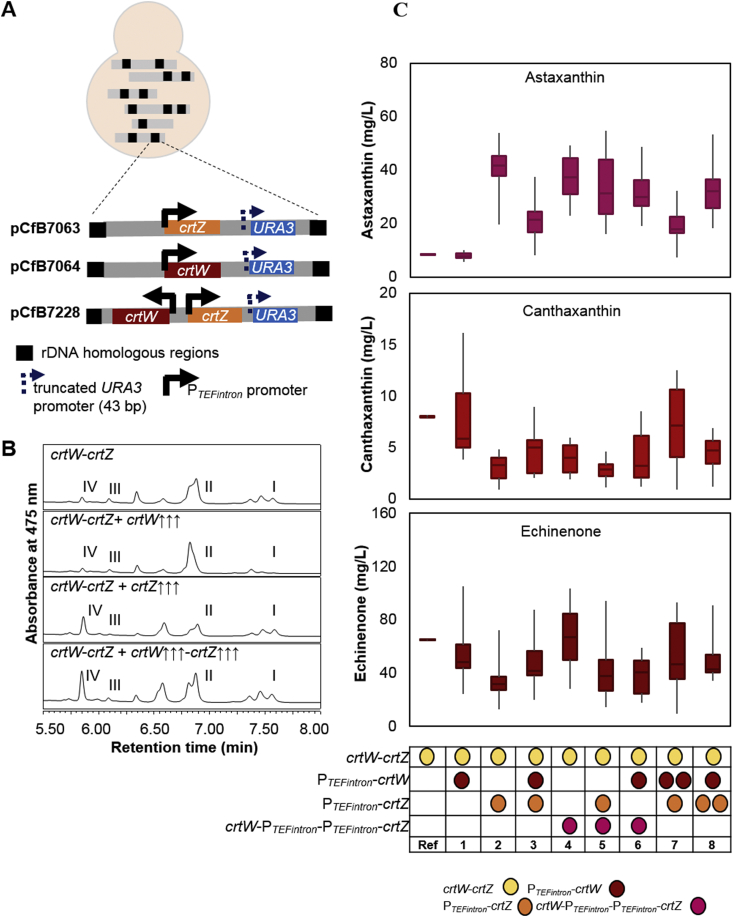

3.5. Optimization of astaxanthin production

Accumulation of astaxanthin intermediates indicated that the flux through the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway was not efficient. The high concentration of echinenone suggests that expression of crtZ might be the rate-limiting step in astaxanthin production in Y. lipolytica. To balance the ratio of crtW and crtZ and redirect the flux towards astaxanthin production, we constructed three different vectors expressing either crtW, crtZ or both genes simultaneously under the control of the strong PTEFintron promoter [9]. The expression vectors also carried two homologous regions to target the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) elements in Y. lipolytica and a URA3 gene (ura3d1 allele) under the regulation of a truncated 43 bp promoter (Fig. 4A) to promote multiple integration events into the rDNA loci [22]. As expected, increasing the copy number of crtW gene had no influence on astaxanthin production and affected only slightly the accumulation of echinenone and canthaxanthin (Fig. 4B and C). On the contrary, increasing the gene copy number of either crtZ alone or both genes simultaneously led to a significant increase in astaxanthin production up to 6-fold. Integrating crtW and crtZ on the same plasmid was more effective than integrating the same genes on separate plasmids, possibly due to the higher overall number of integrations or better pathway balancing. Overall, any of the combinations, which should result in a higher molar ratio of crtZ resulted in improvement of astaxanthin production. These results confirmed that crtZ is the rate-limiting step in the astaxanthin biosynthesis pathway. Our best strain ST7403, with multiple integrations of crtZ and crtW-crtZ, produced 54.6 mg/L astaxanthin (3.5 mg/g DCW).

Fig. 4.

The effect of gene copy number on astaxanthin production. A. Scheme of the strain construction process for increasing the copy number of astaxanthin biosynthetic genes. B. HPLC analysis of carotenoids. Strain abbreviations: crtW-crtZ, astaxanthin producer carrying crtW and crtZ (precursor optimized) [ST7023]; crtW-crtZ + crtW↑↑↑, built by multiple integrations of crtW in ST7023 [ST7399]; crtW-crtZ + crtZ↑↑↑, built by multiple integrations of crtZ in ST7023 [ST7400]; crtW-crtZ + crtW↑↑↑-crtZ↑↑↑, built by multiple integrations of crtW-crtZ in ST7023 [ST7402]. Ι, β-carotene; II, echinenone; III, canthaxanthin; IV, astaxanthin. C. The box plot represents the effect of gene copy number adjustment on the production of astaxanthin and its intermediates. Different combination of additional copies of either crtW, crtZ or both genes under the control of PTEFintron were introduced in the astaxanthin platform strain ST7023. Strain abbreviations: Ref, reference strain ST7023; 1, ST7399; 2, ST7400; 3, ST7401; 4, ST7402; 5, ST7403; 6, ST7404; 7, ST7405; 8, ST7406. Ten individual isolates from each construct were cultivated in YP+8%glucose in 96 deep-well-plates for 72 h.

4. Discussion

Production of high-value carotenoids via biotechnology is an attractive alternative to extraction from plant materials and to chemical synthesis. However, the strains need to be improved before the fermentation processes can become price competitive.

In this study, we engineered Y. lipolytica for the production of a very high-value carotenoid - astaxanthin. As the first step, we screened 14 different Y. lipolytica strains to identify a strain with the best natural potential. The strains varied significantly both in the titer of β-carotene and in genetic amenability. This type of screening can be recommended, particularly in the beginning of a strain development program, as also shown by Friedlander et al. for lipid production [23].

As the next step, we evaluated the effect of modulating the expression of HMG1 and crtE/GGS1 in the mevalonate pathway on β-carotene production. Interestingly, our optimal combinations were different from what was reported for other yeasts. In Candida utilis, the expression of the truncated HMG1 was more effective than the expression of the full-length HMG1, leading to 2-fold increase in lycopene production [24]. In S. cerevisiae, most of the earlier reports expressed truncated HMG1 to enhance isoprenoids production [8], [14]. In Y. lipolytica, full-length HMG1 was overexpressed to enhance lycopene and limonene production [11], [19]. During the preparation of this manuscript, a report by Gao et al. was published, where they overexpressed a truncated HMG1 sequence in Y. lipolytica and obtained a 134% increase in β-carotene production in comparison to the parental strain [25]. However, a comparison between the performance of full and truncated HMG1 variants on enhancing isoprenoid production has not been reported. In our study, the optimal combination was obtained from co-expression of GGS1/crtE with HMG1, not truncated HMG1.

We have further investigated the potential of Y. lipolytica for astaxanthin production. Expression of the crtS and crtR resulted in the production of small amounts of astaxanthin intermediates, but not astaxanthin. In S. cerevisiae expressing the same genes combination, the production of astaxanthin was very weak [8]. Expression of cytochrome P450 enzyme (crtS) and its partner in heterologous hosts is a challenge. Improper folding or anchoring of the proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane can lead to inactivity of the enzymes [26]. Moreover, co-localization of the two enzymes in the same organelle is needed for proper functioning of the pathway [8]. On the other hand, expression of bacterial cytosolic astaxanthin biosynthetic genes crtW and crtZ resulted in production of astaxanthin and its intermediates in our strain. Accumulation of intermediates rather than astaxanthin clearly indicated that the conversion of β-carotene to astaxanthin was not efficient. Proper pathway balancing and more copies of the astaxanthin biosynthetic enzymes were necessary to push the flux towards astaxanthin. We demonstrated that multiple integrations of crtZ and crtW resulted in boosting astaxanthin production and decreased the accumulation of intermediates. The highest astaxanthin titer of 54.6 mg/L (3.5 mg/g DCW) was achieved in 96 deep-well cultivation. Scaling the cultivation of this strain to controlled bioreactors and optimizing the media and fermentation conditions is expected to increase the titer and content much further. Production of astaxanthin in Y. lipolytica was previously reported in a patent [27], but the titer or cellular content of astaxanthin were not indicated, so it is not possible to compare the performance of those strains to the ones generated in this study. Future efforts on strain improvement may include overexpressing β-ketolase and hydrolase with higher activity than bacterial crtW and crtZ e.g., bkt and crtZ from the green algae H. pluvialis as reported in Ref. [28]. In addition, further improvement of the mevalonate pathway flux and repressing competing pathways, such as lipid biosynthesis, are viable strategies to address for further improving astaxanthin biosynthesis in Y. lipolytica.

5. Conclusion

In this work, we engineered Y. lipolytica for the production of β-carotene and further astaxanthin. We identified crtZ as a critical step in conversion of β-carotene into astaxanthin and resolved this by introducing multiple copies of the enzyme into the genome. The astaxanthin-producing Y. lipolytica shows great promise for employment in biological astaxanthin production.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (grant number NNF15OC0016592). BAD was supported by the ERASMUS Traineeship program. We acknowledge Mette Kristensen for technical assistance on HPLC analysis.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synbio.2017.10.002.

Contributor Information

Kanchana Rueksomtawin Kildegaard, Email: karu@biosustain.dtu.dk.

Belén Adiego-Pérez, Email: belen.adiego@gmail.com.

David Doménech Belda, Email: daviddomenechbelda@gmail.com.

Jaspreet Kaur Khangura, Email: jaspreetjk@hotmail.com.

Carina Holkenbrink, Email: cahol@biosustain.dtu.dk.

Irina Borodina, Email: irbo@biosustain.dtu.dk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Panis G., Carreon J.R. Commercial astaxanthin production derived by green alga Haematococcus pluvialis: a microalgae process model and a techno-economic assessment all through production line. Algal Res. 2016;18:175–190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guerin M., Huntley M.E., Olaizola M. Haematococcus astaxanthin: applications for human health and nutrition. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:210–216. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodríguez-Sáiz M., de la Fuente J.L., Barredo J.L. Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous for the industrial production of astaxanthin. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;88:645–658. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2814-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson E.A., LewisEWIS M.J. Astaxanthin formation by the yeast Phaffia rhodozyma. Microbiology. 1979;115:173–183. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitenbach J., Visser H., Verdoes J.C., AJJ van Ooyen, Sandmann G. Engineering of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase levels and physiological conditions for enhanced carotenoid and astaxanthin synthesis in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:755–761. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gassel S., Schewe H., Schmidt I., Schrader J., Sandmann G. Multiple improvement of astaxanthin biosynthesis in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous by a combination of conventional mutagenesis and metabolic pathway engineering. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35:565–569. doi: 10.1007/s10529-012-1103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gassel S., Breitenbach J., Sandmann G. Genetic engineering of the complete carotenoid pathway towards enhanced astaxanthin formation in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous starting from a high-yield mutant. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:345–350. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5358-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ukibe K., Hashida K., Yoshida N., Takagi H. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for astaxanthin production and oxidative stress tolerance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7205–7211. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01249-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai M., Stephanopoulos G. Engineering the push and pull of lipid biosynthesis in oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for biofuel production. Metab Eng. 2013;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H., Zhang L., Chen H., Chen Y.Q., Chen W., Song Y. Enhanced lipid accumulation in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica by over-expression of ATP:citrate lyase from Mus musculus. J Biotechnol. 2014;192:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthäus F., Ketelhot M., Gatter M., Barth G. Production of lycopene in the non-carotenoid-producing yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:1660–1669. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03167-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye R.W., Sharpe P.L., Zhu Q. Bioengineering of oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for lycopene production. Methods Mol Biol Clifton N. J. 2012;898:153–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-918-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stovicek V., Borodina I., Forster J. CRISPR–Cas system enables fast and simple genome editing of industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Metab Eng Commun. 2015;2:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.meteno.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verwaal R., Wang J., Meijnen J.-P., Visser H., Sandmann G., van den Berg J.A. High-level production of beta-carotene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by successive transformation with carotenogenic genes from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4342–4350. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holkenbrink C, Dam MI, Kildegaard KR, Beder J, Dahlin J, Doménech Belda D, et al. EasyCloneYALI: CRISPR/Cas9-based synthetic toolbox for engineering of the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. [Manuscript submitted]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Chen D.C. One-step transformation of the dimorphic yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:232–235. doi: 10.1007/s002530051043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ro D.-K. Production of the antimalarial drug precursor artemisinic acid in engineered yeast. Nature. 2006;440:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature04640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donald K.A., Hampton R.Y., Fritz I.B. Effects of overproduction of the catalytic domain of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase on squalene synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3341–3344. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3341-3344.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao X., Lv Y.-B., Chen J., Imanaka T., Wei L.-J., Hua Q. Metabolic engineering of oleaginous yeast Yarrowia lipolytica for limonene overproduction. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:214. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0626-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan J., Ching C.-B. Dynamic control of ERG9 expression for improved amorpha-4,11-diene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:38. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcaíno J., Barahona S., Carmona M., Lozano C., Marcoleta A., Niklitschek M. Cloning of the cytochrome p450 reductase (crtR) gene and its involvement in the astaxanthin biosynthesis of Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juretzek T., Le Dall M.-T., Mauersberger S., Gaillardin C., Barth G., Nicaud J.-M. Vectors for gene expression and amplification in the yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Yeast. 2001;18:97–113. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20010130)18:2<97::AID-YEA652>3.0.CO;2-U. 2<97::AID-YEA652>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedlander J., Tsakraklides V., Kamineni A., Greenhagen E.H., Consiglio A.L., MacEwen K. Engineering of a high lipid producing Yarrowia lipolytica strain. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016:9. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0492-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada H., Kondo K., Fraser P.D., Miura Y., Saito T., Misawa N. Increased carotenoid production by the food yeast Candida utilis through metabolic engineering of the isoprenoid pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2676–2680. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2676-2680.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao S., Tong Y., Zhu L., Ge M., Zhang Y., Chen D. Iterative integration of multiple-copy pathway genes in Yarrowia lipolytica for heterologous β-carotene production. Metab Eng. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schrader J., Bohlmann J. vol. 148. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2015. (Biotechnology of isoprenoids). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharpe P.L., Ye R.W., Zhu Q.Q. 2014. Carotenoid production in a recombinant oleaginous yeast. US8846374 B2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou P., Xie W., Li A., Wang F., Yao Z., Bian Q. Alleviation of metabolic bottleneck by combinatorial engineering enhanced astaxanthin synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2017;100:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.