Abstract

Current medication for gastric cancer patients has a low success rate with resistance and side effects. According to recent studies, γ-secretase inhibitors is used as therapeutic drugs in cancer. Moreover, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) is a natural compound proposed for the treatment/chemo-prevention of cancers. The aim of this study was to explore the effects of ATRA in combination with N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) as γ-secretase inhibitor on viability and apoptosis of the AGS and MKN-45 derived from human gastric cancer. AGS and MKN-45 gastric cancer cell lines were treated with different concentrations of ATRA or DAPT alone or ATRA plus DAPT. The viability, death detection and apoptosis of cells was examined by MTT assay and Ethidium bromide/acridine orange staining. The distribution of cells in different phases of cell cycle was also evaluated through flow cytometry analyses. In addition, caspase 3/7 activity and the expression of caspase-3 and bcl-2 were examined. DAPT and ATRA alone decreased gastric cancer cells viability in a concentration dependent manner. The combination of DAPT and ATRA exhibited significant synergistic inhibitory effects. The greater percentage of cells were accumulated in G0/G1 phase of cell cycle in combination treatment. The combination of DAPT and ATRA effectively increased the proportion of apoptotic cells and the level of caspase 3/7 activities compared to single treatment. Moreover, augmented caspase-3 up-regulation and bcl-2 down-regulation were found following combined application of DAPT and ATRA. The combination of DAPT and ATRA led to more reduction in viability and apoptosis in respect to DAPT or ATRA alone in the investigated cell lines.

Keywords: DAPT, ATRA, Gastric cancer, Caspase 3/7, bcl-2, Combination therapy

Introduction

Despite an overall worldwide decline in incidence, gastric carcinoma (GC) remains still the fifth most frequently diagnosed cancer and the third most prevalent causes of cancer-related mortality in the world (Brzozowa et al. 2013; Riquelme et al. 2015). Given the absence of significant symptoms in the early stages of the disease and lack of reliable methods for early detection (Ju et al. 2015; Riquelme et al. 2015), a large number of GC cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage (Li et al. 2015). The only solution available, for GC patients is systemic chemotherapy that lengthens survival rates of patients (Brzozowa et al. 2013). One of the easy and most common systems used to classify the GC is Lauren classification, which divides the GC into two major classes as intestinal and diffuse. Intestinal-type shows a glandular appearance in histocytologic studies (Dicken et al. 2005). About 95% of GCs are adenocarcinoma with glandular cell origin (Brzozowa et al. 2013).

Cancer cells have some alterations in their signaling pathways, which controls cell proliferation, senescence and apoptosis. The Notch pathway is a highly conserved cell signaling mechanism that plays pivotal roles in many fundamental cellular processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation and stem cell maintenance (Brzozowa et al. 2013; Katoh and Katoh 2007; Li et al. 2014). The Notch canonical pathway is initiated by a receptor-ligand interaction between two neighboring cells. Upon ligand binding, two proteolytic cleavages mediated by both ADAM/TACE metalloproteinase and γ-secretase occur in the notch receptors and this process leads to release the notch intracellular domain (NICD). NICD translocates to the nucleus and activates a number transcriptional factors like hes1 and hey1 (Mori et al. 2012; Nefedova and Gabrilovich 2008).

Notch signaling acts on oncogene or tumor suppressor gene, depending on the tissue and cellular context (Aster et al. 2016; Nowell and Radtke 2017). Oncogenic function of Notch and its association with different malignancies such as ovarian cancer, breast cancer, multiple myeloma, pancreatic cancer, melanoma, GC, head neck squamous cell carcinoma (Feng et al. 2017; Han et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2008, 2010; Wu et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2016) as well as its contribution in drug resistance have well been documented (Su et al. 2016). In the gut, Notch maintains proliferating, undifferentiated state for stem/progenitor cells and prohibits their differentiation into functionally mature intestinal epithelial cells (Nowell and Radtke 2017). Notch receptors, (named as notch1–4) are so important in GCs that can be used as prognostic marker of GC (Brzozowa et al. 2013). Activation of the NOTCH1 signaling was also related with metastasis of human malignancies (Brzozowa-Zasada et al. 2017). A study suggested that inhibition of Notch receptors by γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) suppressed cell proliferation and induced cell apoptosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Li et al. 2014). Piazzi et al. (2011) showed that DLL1, a Notch receptor ligand, increases the Notch1 expression in different gastric cell lines including MKN-45 and AGS and some of human GC samples.

It has been shown that Notch1 and hes1 expression is elevated in cancer stem cells (CSCs) (Yan et al. 2014) and the expression of Notch1 was significantly increased in GC cell lines and tumor tissues rather than normal gastric mucosa cell lines and tissues. Remarkably, Notch1 level is more elevated in metastatic specimen compared to patient without metastases (Li et al. 2014). A study suggested that Notch1 activation could sustain oncogenic function of notch through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-PKB/Akt-dependent pathway and inhibit p53-induced apoptosis in human cervical tumors (Nair et al. 2003). The other function of Notch signaling is its inhibitory effect on cell differentiation. Li et al. (2015a) showed that gasteric CSC (CD44+) overexpresses the Notch receptor so using the γ-secretase inhibitor can down-regulate the Notch down-stream targets such as Hes1 and EMT markers (Li et al. 2015a). So targeting the Notch signaling pathway might be potential therapy. Furthermore, it was proven that inhibiting the Notch signaling can reduce the growth of organoids driven from human gastric stem cells (Dedhia et al. 2016). γ-secretase inhibitors (GSI) offer a promising approach to block Notch signaling (Lee et al. 2015; Yuan et al. 2015). N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT), a dipeptide γ-secretase inhibitor, can suppress cellular proliferation, arrest cell cycle and induce apoptosis in human cancer cell lines (Mori et al. 2012; Pannuti et al. 2010; Yao et al. 2013). Although the clinical use of GSIs might be limited due to their toxic side effects especially in the gastrointestinal tract, preclinical studies have demonstrated that the toxicity of these compounds could be declined by lowering the dose of GSIs in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents (Li et al. 2016).

All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), a natural derivative of vitamin A, is known as a potent antitumor agent causing growth inhibition, differentiation and apoptosis induction in several human cancers including thyroid (Hu et al. 2014), skin (Liu et al. 2015b), gastric (Ju et al. 2015), breast (Zanetti et al. 2015), lung (Poulain et al. 2009), and prostate malignancies (Chen et al. 2012). Therapeutic usage of ATRA has been approved for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) and other hematological diseases based on its ability in cell differentiation associated with growth inhibition (Liu et al. 2015a; Zhang et al. 2007). Additionally, different studies have demonstrated that using ATRA can increase survival times in human advanced GC (Hu et al. 2012; Nguyen et al. 2016). Retinoids exert their functions through two types of nuclear retinoid receptors including RAR (α/β/γ) and RXR (α/β/γ) (Lee et al. 2010; Li et al. 2009). Accumulating evidence has indicated that ATRA plays its anti-proliferative role in GC through up-regulating RARα expression (Liu et al. 2001). ATRA treatment could stabilize and accumulate P53 which in turn activates several apoptosis-related molecules, including Bax, PUMA, caspase-9, Bid, caspase-8, and caspase-3 (Heo et al. 2015).

It has been shown that the expression of retinoic acid (RA) signaling elements is linked to Notch signaling (Nowell and Radtke 2017; Vauclair et al. 2007). Ying and colleagues revealed that Notch signaling is the most responsive pathway in retinoic acid treatment. Notch signaling down-stream genes were negatively regulated with ATRA treatment in glioblastoma stem cells (Ying et al. 2011). In addition, anti-migratory and anti-proliferative activities of ATRA in HCC1599 breast cancer cells were mediated through Notch1 inhibition (Zanetti et al. 2015). Treatment of renal carcinoma cells with retinoic acid chalcone resulted in a substantial decrease in Notch1 and Jagged1 protein level (Li et al. 2015b). We previously have shown that the expression of Notch1 and Hes1 are reduced in MKN-45 GC cell lines following ATRA treatment (Niapour et al. 2016b).

Application of combination therapy is widely used to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of drugs and decreasing the drug resistance development or their side effects (Foucquier and Guedj 2015). Given the toxic side effects of GSIs such as gastrointestinal toxicity and inflammation (Li et al. 2016) and advantages of retinoids in arresting and differentiation of GC lines, in current study we evaluated the effects of DAPT and ATRA co-treatment on two gastric driven cell lines; MKN-45 and AGS.

Methods and materials

Reagents and cell line

All chemicals including ATRA, DAPT and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise mentioned. Human GC cell lines, AGS and MKN-45, were obtained from the National Cell Bank of Iran (Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran).

Cell culture and treatment

Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 104 U/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were seeded into 96-well culture plates at densities of 1 × 103 cells/ml and incubated overnight. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of DAPT (5, 10, 20, 30 and 50 µM), ATRA (5, 10, 15, 20, 25 µM) and their combination in their logarithmic growth for 2 days. Negative controls received the same amount of DMSO as a solvent of the drugs.

MTT assay

MTT assay was performed as described elsewhere (Niapour et al. 2016a; Sharifi Pasandi et al. 2017). Briefly, at the end of the treatment, 20 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) was added to 180 μl medium in each well and plates were incubated in the dark for 4 h at 37 °C. The culture supernatants were then replaced with 200 μl of DMSO, mixed by shaking at room temperature for 10 min until the formazan crystals dissolved. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy HT, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) and reported as the percentage of cell viability in comparison to control. All the tests were implemented in triplicates from three independent experiments. Cell viability data were fitted to 4-parameter logistics function in Sigma Plot software V12 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) to calculated Efficacy concentrations, EC50. EC50 was defined as concentration causing 50% of each drugs maximum effect.

In order to discriminate the cytocidal and growth inhibition effects of drugs alone and their combination Monks method was used (Ibrahim et al. 2012);

| 1 |

and represent the cytostatic or cell death effects of drugs, respectively. The ODzero, ODcontrol and the ODtreated are the optical densities at the moment of drug addition, untreated and treated wells, respectively (Ibrahim et al. 2012).

Furthermore, the possibility of synergistic effect for implemented agents was evaluated by calculating the combination index (CI) based on Bliss Independence equation (Foucquier and Guedj 2015);

| 2 |

where EA, EB, and EAB are the cell “cytocidal and inhibitory” effects of drug A, drug B and their combination, respectively. Accordingly, CI > 1, CI < 1 and CI = 1 indicate that the combination has lesser, greater or similar growth inhibition than expected additive values (Foucquier and Guedj 2015).

Cell cycle analyses by flow cytometry

At the completion of the respective treatments, cells were trypsinized and suspended in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Single cell suspensions were fixed using 70% ice cold ethanol for 4 h at 4 °C. The fixed cells were then permeabilized and stained with PBS containing 10 μg/ml DAPI and 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature. Flow cytometry was performed with Partec Space Flow Cytometer (Partec GmbH, Jettingen-Scheppach, Germany) by capturing at least 10,000 events for each sample (Sharifi Pasandi et al. 2017). The distribution of cells in the different cell cycle phases was analyzed with FlowJO V10 software (Tree Star Inc, Ashland, OR, USA).

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide (AO/EB) staining

After treatment, the 96 well plates were centrifuged for 5 min (278 g, 2000 rpm) at 4 °C. Then, acridine orange (AO)/ethidium bromide (EB) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) dye mix (100 μg/ml AO and 100 μg/ml EB) was prepared in PBS. After 5 min incubation at room temperature in the dark, AGS cells were analyzed with an inverted fluorescence light microscope (OLYMPUS Model IX71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Based on this method, AO permeates all cells and makes the nuclei appear green. EB is only taken up by cells whose cytoplasmic membrane integrity is lost and stains the nucleus red. EB also dominates over AO.

Caspase 3/7 activity assay

The activity of caspase 3/7, the key executioners of apoptosis, were measured using the Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) as described by the manufacturer’s manual. Briefly, following treatment cells were collected by trypsinization and centrifugation for 10 min at 2000 rpm. Then, 1:1 ratio of Caspase-Glo® 3/7 reagent and cell suspension containing 1 × 104 cells were added into white-walled 96 well plates and incubated at room temperature for 3 h. The cleavage of tetrapeptide sequence DEVD by caspase enzymes correlates with luminescence intensity at 570 nm emission measured by plate-reading luminometer (Synergy HT, BioTek). Data are reported as the relative caspase activity in comparison to control.

Reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction analyzes

Total RNAs were isolated from the AGS cells using the Trizol reagent (Gibco) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 μg of total mRNA was transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using Revert Aid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Forward and reverse primer sequences for each gene were as follows:

Gapdh; Forward: CATCACCATCTTCCAGGAGC, Reverse: CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG

caspase3; Forward:CTGTGGCTGTGTATCCGTGG, Reverse: CTGCTCCTTTTGCTGTGATCT

bcl2: Forward: CTGGGATGCCTTTGTGGAA, Reverse: GTGTGTGTGTGTGTCTGTCTGTG

Standard polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed using Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and were involved in 35 cycles with annealing temperatures as 54 °C, 53 °C and 53 °C, respectively. The bond sizes were 575 bp for gapdh, 493 bp for caspase-3 and 299 bp for bcl-2. The final products were loaded on 1.2% agarose gels and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The gels were illuminated by UV light and photographed using UVITEC System (UVITEC, Cambridge, UK). Changes in gene expression in treated and untreated groups were quantified by densitometric analysis protocol of Image J software version 1.5 (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the mean ± SD from at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SPSS version 15.0 software. The Tukey-HSD was used to make a statistical comparison between groups and One-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the significance of differences in the mean values. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cytotoxic effects of DAPT, ATRA and their combination on human GC cell lines

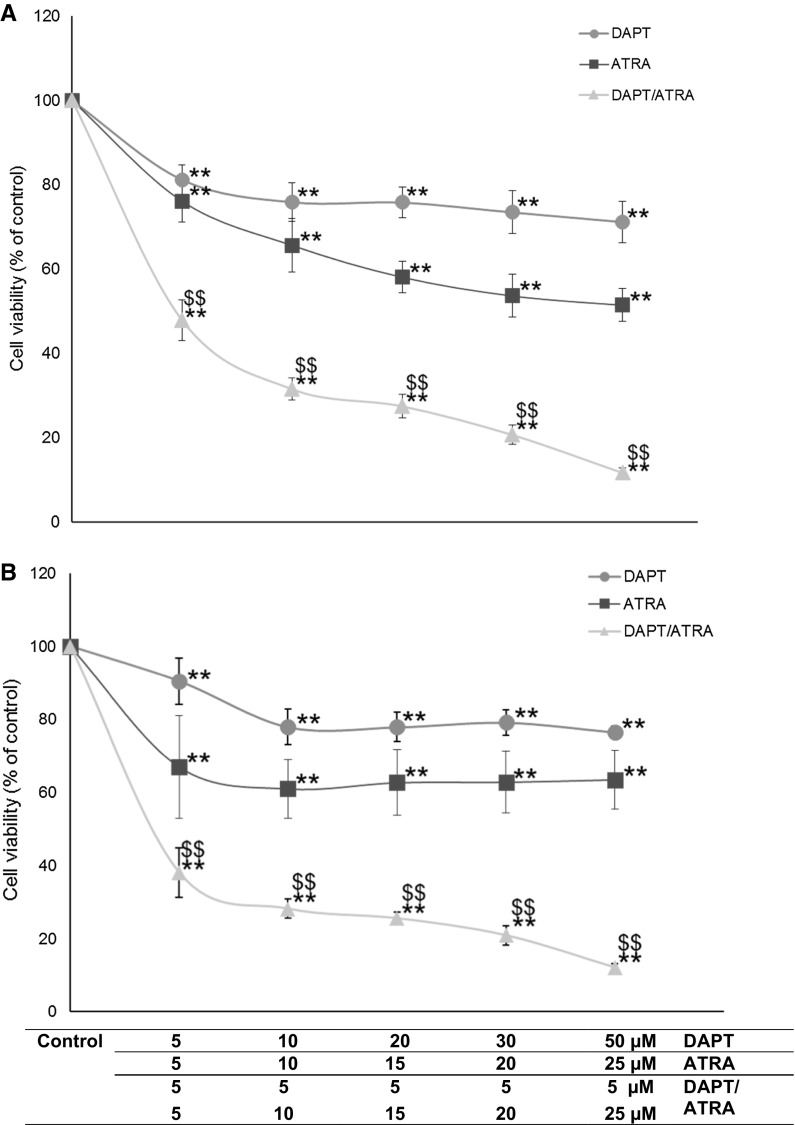

First, we determined the growth inhibitory effect DAPT in AGS and MKN-45 cells. GC cells were treated with increasing DAPT doses (5–50 µM). The results of MTT assay showed that DAPT could reduce the viability of gastric cancer cell lines in dose dependent manners (Fig. 1). The cells were also cultured in the presence of various concentration of ATRA. Likewise, ATRA exerts a decrement in the cell viability in a dose dependent manner. The mean estimated EC50 values for DAPT and ATRA were calculated as; 7.46 and 9.08 µM for AGS and 5.19 and 2.63 µM for MKN-45 cells, respectively. To explore whether different concentrations of ATRA can enhance the cytotoxicity effect of DAPT on GC cells, we conducted a combination treatment. Cells were treated with a combination of both agents in concentrations lower than DAPT EC50 (5 µM) and ATRA concentrations ranging between 5 and 25 μM (Fig. 1). Although DAPT or ATRA alone exhibited a decrease in AGS and MKN-45 cells viability, the combined application of DAPT and ATRA showed a stronger decline in the viability of GC cells (P < 0.001). Specifically, the greatest cytotoxic effect was observed in the combination of 5 µM DAPT and 25 µM ATRA in which the AGS and MKN-45 cellular viability plummeted dramatically to ~ 12% in comparison to ATRA and DAPT alone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

DAPT, ATRA and their combination effects on GC cells viability. AGS (a) and MKN-45 (b) cells at passages 6–12 were treated with DAPT, ATRA and combination of DAPT (5 µM) with various ATRA concentrations for 48 h. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6). **P < 0.05 versus control, **P < 0.001 versus control, $$P < 0.001 versus DAPT only and ATRA only

The mechanism of combination therapy effectiveness and CI were estimated based on Monks and Bliss equations, respectively, as described in the Materials and Methods section. CI values were less than unit at all concentrations indicating the synergistic effect of DAPT and ATRA. Combination treatment led to cell death at ATRA concentrations above 20 µM while the prominent effect at lower concentration was cytostatic (Table 1).

Table 1.

The “cytocidal and inhibitory” effects of DAPT and ATRA on MKN-45 and AGS cell lines and their combination effects at various concentrations of ATRA in the presence of 5 µM DAPT

| Cell line | DAPT (µM) | EDAPT (growth inhibition) | ATRA (µM) | EATRA (growth inhibition) | EDAPT/ATRA (growth inhibition) | CI | Mechanism of effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS | 5 | 0.19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | Cytostatic |

| 5 | 0.24 | 0.52 | 0.74 | Cytostatic | |||

| 10 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.68 | Cytostatic | |||

| 15 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 0.73 | Cytostatic | |||

| 20 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 0.71 | Cell death | |||

| 25 | 0.49 | 0.88 | 0.66 | Cell death | |||

| MKN-45 | 5 | 0.095 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | Cytostatic |

| 5 | 0.33 | 0.62 | 0.64 | Cytostatic | |||

| 10 | 0.39 | 0.72 | 0.62 | Cytostatic | |||

| 15 | 0.37 | 0.74 | 0.58 | Cytostatic | |||

| 20 | 0.37 | 0.79 | 0.55 | Cell death | |||

| 25 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 0.48 | Cell death |

The last column shows the mechanism of combination effectiveness

NA not applicable

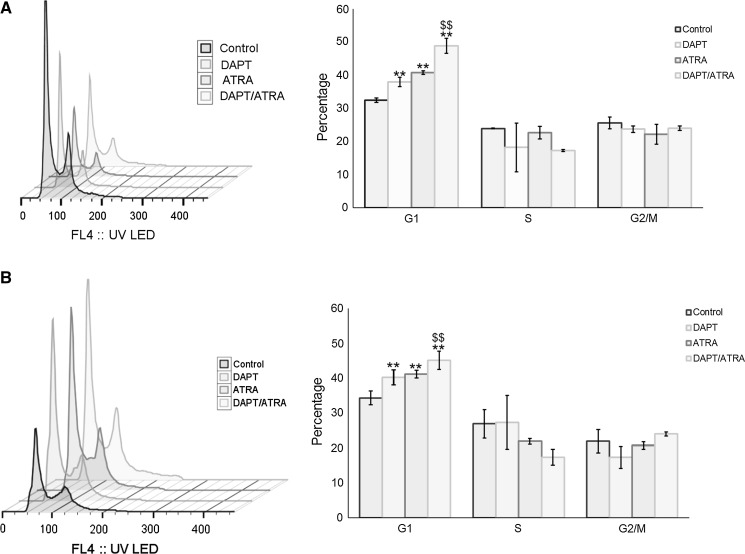

Distribution of cell cycle in human GC cells by flow cytometry

The DNA contents of control groups and cells treated by DAPT, ATRA and their combination were measured through flow cytometry (Fig. 2) and the percentages of cells in cycle phases were plotted as population histogram. The results indicated that DAPT and ATRA treatment increased cell population in G1 phase comparing to control. In co-treated cells, more cells accumulated in G0/G1 phase than for the control or the single-treated groups (P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Population histogram of AGS and MKN-45 in presence of DAPT, ATRA and their combination. Population histogram of AGS (a) and MKN-45 (b) cells at passages 8–12 in normal untreated cells and following treatment with 5 µM of DAPT, 25 µM of ATRA and their combination are shown, respectively. The columnar graph in a and b demonstrated the distribution of cells in different phases of cell cycle implementing FlowJO software. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.001 versus control, $$P < 0.001 versus DAPT only and ATRA only

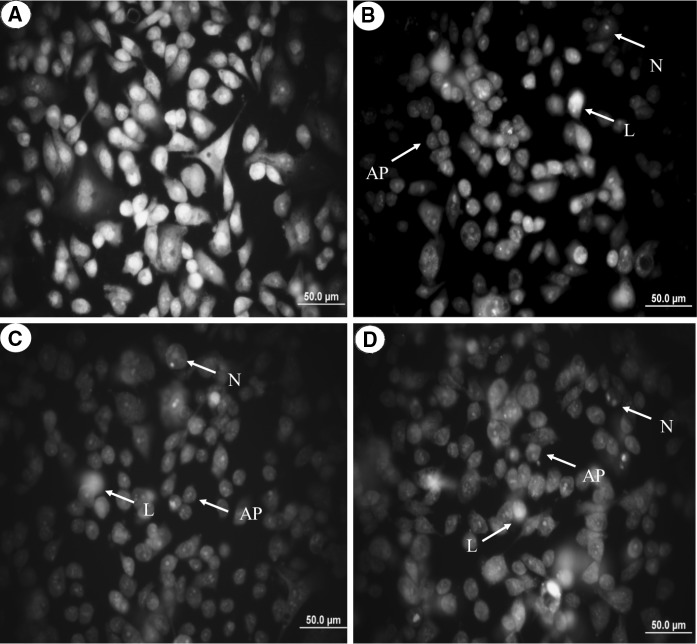

Morphological analysis of human GC cells by AO/EB staining

The morphological characteristics of the treated AGS cells with DAPT, ATRA or their combination were determined by AO/EB staining and analyzed under a fluorescent microscope (Fig. 3). Based on the AO/EB staining results, lots of untreated cells displayed normal morphology without any changes in their nucleus (Fig. 3a). After 48 h of treatment, cancer cells demonstrated a series of morphological alterations designated as typical evidence of apoptosis (Fig. 3b–d). Cells treated with the drugs combination displayed a greater percentage of apoptotic cells (62.17 ± 1.8%) than those treated with either DAPT (27.19 ± 2.9%) or ATRA (35.66 ± 2.7%) alone (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Morphological changes in AGS cells following treatment with DAPT, ATRA and their combination. Representative photomicrographs have shown apoptosis induction in AGS cells at passages 7–10 following DAPT (5 µM), ATRA (25 µM) and their combination treatment (n = 3). a Normal untreated cells, b DAPT-treated cells, c ATRA-treated cells, d ATRA/DAPT treated cells. L live cells, AP apoptotic cells, N necrotic cells

Table 2.

Apoptosis induction of DAPT (5 µM), ATRA (25 µM) and their combination on AGS cells

| Groups | Live cells (%) | Apoptotic cells (%) | Necrotic cells (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGS control | 90.47 ± 3.2 | 7.66 ± 1.02 | 1.87 ± 0.8 |

| DAPT treated AGS cells | 68.02 ± 2.7** | 27.19 ± 2.9** | 4.78 ± 0.3 |

| ATRA treated AGS cells | 58.51 ± 2.5** | 35.66 ± 2.7** | 5.83 ± 0.6 |

| DAPT/ATRA treated AGS cells | 32.95 ± 1.95** | 62.17 ± 1.8** | 4.87 ± 1 |

Data are presented as a percentage of cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.001 versus control

Evaluation of the caspase 3/7 enzyme activity in human GC cells

To quantify the induction of apoptosis following DAPT, ATRA and combinational administration, the activity of caspase 3/7, as key executioners of apoptosis, was examined. Co-treated cells showed higher caspase activity than ATRA and DAPT groups (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

DAPT, ATRA and their combination on Caspase 3/7 activity. AGS (a) and MKN-45 (b) cells at passages 9–11 were treated with DMSO vehicle control, DAPT only (5 µM), ATRA only (25 µM) and their combinations. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.001 versus control, $$P < 0.001 versus DAPT only and ATRA only

Evaluation of the expression levels of the apoptosis-related genes in human GC cells by RT-PCR

The expression of the apoptosis related genes; caspase-3 and bcl-2, in response to DAPT, ATRA and their combination was assessed on AGS cells (Fig. 5). We observed that the combination of DAPT and ATRA led to overexpression of caspase-3. The expression level of anti-apoptotic marker of bcl-2 was declined by single treatment by 25 μM of ATRA and combination treatment (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Effect of DAPT, ATRA and their combination on the expression of caspase-3 and bcl-2 genes. RT-PCR bands and semiquantitative analysis for caspase-3 and bcl-2 genes in DAPT only (5 µM), ATRA only (25 µM) and combination therapy are shown in a, b, respectively. All data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). $$P < 0.001 versus DAPT only and ATRA only

Discussion

Application of combination therapy is widely used to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of drugs and to decrease the drug resistance development or their side effects (Foucquier and Guedj 2015). In this study, AGS and MKN-45 GC cell lines were used in an attempt to clarify the apoptotic and antiproliferative effects of DAPT, ATRA and their combination. Our findings showed that DAPT and ATRA combination can induce more apoptosis in comparison to each agents alone clarified by AO/EB staining, caspase 3/7 assay, Bcl-2 expression and cell viability assays.

GC is suggested to be treated by targeting the Notch signaling. Based on recent studies, Notch receptors (e.g., Notch1–4) (Mori et al. 2012) and Notch ligands (e.g., Jagged1/2) were detected in both samples of gastric premalignant lesions and GC tissues (Katoh and Katoh 2007; Sethi and Kang 2011). Notch1 was reported to be overexpressed in GC tissues, such as intestinal metaplasia. It has been proven that Notch1 overexpression closely associated with tumor size, differentiation grade, depth of invasion, vessel invasion and patient’s survival rate (Cao et al. 2012; Ferrari-Toninelli et al. 2010; Shih Ie and Wang 2007). According to previous reports, disruption of the Notch receptor cleavage by γ-secretase inhibitors and consequently blocking Notch signaling can suppress cell proliferation and induce apoptosis in several cancer models both in vivo and in vitro (Li et al. 2016; Mori et al. 2012). DAPT as a GSI, is an effective compound for fighting GC through blocking Notch signaling (Brzozowa et al. 2013; Yuan et al. 2015). In this study, we demonstrated that DAPT could exert its cytostatic effect on AGS and MKN-45 cells through decreasing cell viability rate in a concentration dependent manner. Regarding the toxic side effects of DAPT at high doses and based on our obtained EC50 values, 5 μM of DAPT was used in combination with ATRA for further studies. Moreover, the evaluation of apoptosis related genes showed that 5 μM of DAPT led to up-regulation of caspase-3 and down-regulation of bcl-2 genes consistent with caspase 3/7 assays. Cell cycle analysis indicated that ATRA, DAPT and the combination of them increased cell population in G0/G1 and arrested the cell cycle in this phase. In the present study, we demonstrated that the administration of ATRA can effectively reduce the viability percentage of AGS and MKN-45 cells in a dose dependent manner and this reduction is more considerable at higher doses. Thus, we continued our experiments with 25 μM of ATRA to explore the apoptosis induction in AGS and MKN-45 cells. In addition to the morphological changes in favor of apoptosis, caspase 3 up-regulation and bcl-2 down-regulation were also observed upon 25 μM ATRA treatment. It was revealed that combination of retinoids and other anti-cancer drugs act synergistically to inhibit cancer cell growth and can induce apoptosis in several malignancies (Miao et al. 2011; Zanetti et al. 2015).

The clinical application of γ-secretase inhibitors might be limited due to their unwanted toxicity especially cytotoxicity in the gastrointestinal tract. This detrimental impact could be related to the blockade of the physiological effects of Notch signaling in normal tissues and dysfunction of vital organs (Wang et al. 2010) due to non-selective and non-specific binding of GSIs (Ferrari-Toninelli et al. 2010). The toxicity of GSIs could be minimized by lowering the dose of these compounds in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents (Lee et al. 2015). In line with our findings, it was found that inhibition of Notch signaling sensitized colon cancer cells to chemotherapy (Riquelme et al. 2015). To determine the synergistic effects of ATRA and DAPT on GC cells, AGS and MKN-45 were co-treated by DAPT and ATRA. Our data showed that DAPT in combination with ATRA reduced cell viability markedly. Obtained CI value, ~ 0.5, showed that these drugs have synergistic effects and their combined effect is higher than the expected values for each drug alone (Table 1). The viability of AGS cell lines was studied by Alizadeh-Navaei et al. using first line standard care of GC chemotherapeutic drugs; Epirubicin, Cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil and their combination (ECF) using MTT. Their results, showed no significant differences between ECF combination and cisplatin or 5-fluorouracil in 48–72 h of treatment (Alizadeh-Navaei et al. 2016). Our apoptosis assay also showed that combined application of DAPT and ATRA had a stronger and significant effect on caspase 3/7 activities and cell viability than the single treatments. We showed that ATRA and DAPT co-treated AGS/MKN-45 cell lines showed cell viability of about 12% which is more effective than values reported by Alizadeh-Navaei on ECF combination, ~ 30–50% (Alizadeh-Navaei et al. 2016). The effective mechanism of combination treatment shifts from cytostatic to cell death at ATRA concentrations higher than 20 µM (Table 1). This finding is in accordance with reports that higher concentrations of ATRA induce apoptosis in gastric cell lines (Fang and Xiao 1998; Miao et al. 2011).

Conclusion

Our study revealed that DAPT and ATRA have synergistic effects on growth inhibition, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in AGS and MKN-45 cell lines. Furthermore, we found that the combination of these drugs was more effective than each agent alone. These results support the hypothesis that the combination of DAPT and ATRA can be used as prospective chemotherapeutics for GC.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a thesis grant for Master of Science from Ardabil University of Medical Sciences. The authors also appreciate Mrs. Sheri Lynn Jalalian as an English expert for reviewing the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Ali Niapour, Phone: +98 4533513424, Email: a.niapour@arums.ac.ir.

Mojtaba Amani, Phone: +98 4533513424, Email: m.amani@arums.ac.ir.

References

- Alizadeh-Navaei R, Rafiei A, Abedian-Kenari S, Asgarian-Omran H, Valadan R, Hedayatizadeh-Omran A. Effect of first line gastric cancer chemotherapy regime on the AGS cell line—MTT assay results. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17:131–133. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aster JC, Pear WS, Blacklow SC. The varied roles of notch in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2016;12:245–275. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-052016-100127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowa M, Mielańczyk L, Michalski M, Malinowski L, Kowalczyk-Ziomek G, Helewski K, Harabin-Słowińska M, Wojnicz R. Role of Notch signaling pathway in gastric cancer pathogenesis. Contemp Oncol. 2013;17:1–5. doi: 10.5114/wo.2013.33765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowa-Zasada M, Piecuch A, Michalski M, Segiet O, Kurek J, Harabin-Slowinska M, Wojnicz R. Notch and its oncogenic activity in human malignancies. Eur Surg. 2017;49:199–209. doi: 10.1007/s10353-017-0491-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Hu Y, Wang P, Zhou J, Deng Z, Wen J. Down-regulation of Notch receptor signaling pathway induces caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis in lung squamous cell carcinoma cells. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 2012;120:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MC, Huang CY, Hsu SL, Lin E, Ku CT, Lin H, Chen CM. Retinoic acid induces apoptosis of prostate cancer DU145 cells through Cdk5 overactivation evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:580736. doi: 10.1155/2012/580736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedhia PH, Bertaux-Skeirik N, Zavros Y, Spence JR. Organoid models of human gastrointestinal development and disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1098–1112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, Mackey JR, Joy AA, Hamilton SM. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005;241:27–39. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000149300.28588.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang JY, Xiao SD. Effect of trans-retinoic acid and folic acid on apoptosis in human gastric cancer cell lines MKN-45 and MKN-28. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:656–661. doi: 10.1007/s005350050152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Xu W, Zhang C, Liu M, Wen H. Inhibition of gamma-secretase in Notch1 signaling pathway as a novel treatment for ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:8215–8225. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari-Toninelli G, Bonini SA, Uberti D, Buizza L, Bettinsoli P, Poliani PL, Facchetti F, Memo M. Targeting Notch pathway induces growth inhibition and differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:1231–1243. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucquier J, Guedj M. Analysis of drug combinations: current methodological landscape. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2015;3:e00149. doi: 10.1002/prp2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Ma I, Hendzel MJ, Allalunis-Turner J. The cytotoxicity of gamma-secretase inhibitor I to breast cancer cells is mediated by proteasome inhibition, not by gamma-secretase inhibition. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R57. doi: 10.1186/bcr2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo SH, Kwak J, Jang KL. All-trans retinoic acid induces p53-depenent apoptosis in human hepatocytes by activating p14 expression via promoter hypomethylation. Cancer Lett. 2015;362:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu KW, Chen FH, Ge JF, Cao LY, Li H. Retinoid receptors in gastric cancer: expression and influence on prognosis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1809–1817. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.5.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu KW, Pan XH, Chen FH, Qin R, Wu LM, Zhu HG, Wu FR, Ge JF, Han WX, Yin CL, Li HJ. A novel retinoic acid analog, 4-amino-2-trifluoromethyl-phenyl retinate, inhibits gastric cancer cell growth. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33:415–422. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2013.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim T, Mercatali L, Sacanna E, Tesei A, Carloni S, Ulivi P, Liverani C, Fabbri F, Zanoni M, Zoli W, Amadori D. Inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation in repeated and non-repeated treatment with zoledronic acid. Cancer Cell Int. 2012;12:48. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-12-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju J, Wang N, Wang X, Chen F. A novel all-trans retinoic acid derivative inhibits proliferation and induces differentiation of human gastric carcinoma xenografts via up-regulating retinoic acid receptor beta. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:856–865. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh M, Katoh M. Notch signaling in gastrointestinal tract (review) Int J Oncol. 2007;30:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yoon JH, Yu SJ, Chung GE, Jung EU, Kim HY, Kim BH, Choi DH, Myung SJ, Kim YJ, Kim CY, Lee HS. Retinoic acid and its binding protein modulate apoptotic signals in hypoxic hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2010;295:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Kim SJ, Choi IJ, Song J, Chun KH. Targeting Notch signaling by gamma-secretase inhibitor I enhances the cytotoxic effect of 5-FU in gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metas. 2015;32:593–603. doi: 10.1007/s10585-015-9730-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ng EK, Ng YP, Wong CY, Yu J, Jin H, Cheng VY, Go MY, Cheung PK, Ebert MP, Tong J, To KF, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Ip NY, Leung WK. Identification of retinoic acid-regulated nuclear matrix-associated protein as a novel regulator of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:691–698. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Peng Y, Liu YM, Wang LL, Wu XL. Gastric cancer cell growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition are inhibited by gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:2160–2164. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Wang DL, Wu YZ, Nian WQ, Wu ZJ, Li Y, Ma HW, Shao JH. Gastric tumor-initiating CD44 cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition are inhibited by gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:3293–3299. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li QC, Li HJ, Liu S, Liang Y, Wang X, Cui L. Inhibition of gamma-secretase by retinoic acid chalcone (RAC) induces G2/M arrest and triggers apoptosis in renal cell carcinoma Int J. Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2400–2407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Lin X, Zhang JR, Li Y, Lu J, Huang FC, Zheng CH, Xie JW, Wang JB, Huang CM. The expression of presenilin 1 enhances carcinogenesis and metastasis in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:10650–10662. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Wu Q, Chen ZM, Su WJ. The effect pathway of retinoic acid through regulation of retinoic acid receptor alpha in gastric cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:662–666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Wen Q, Chen XL, Yang SJ, Gao L, Gao L, Zhang C, Li JL, Xiang XX, Wan K, Chen XH, Zhang X, Zhong JF. All-trans retinoic acid arrests cell cycle in leukemic bone marrow stromal cells by increasing intercellular communication through connexin 43-mediated gap junction. J Hematol Oncol. 2015;8:110. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0212-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZM, Wang KP, Ma J, Guo Zheng S. The role of all-trans retinoic acid in the biology of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:553–557. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao R, Xu T, Liu L, Wang M, Jiang Y, Li J, Guo R. Rosiglitazone and retinoic acid inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in the HCT-15 human colorectal cancer cell line. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:413–417. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M, Miyamoto T, Yakushiji H, Ohno S, Miyake Y, Sakaguchi T, Hattori M, Hongo A, Nakaizumi A, Ueda M, Ohno E. Effects of N-[N-(3, 5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) on cell proliferation and apoptosis in Ishikawa endometrial cancer cells. Hum Cell. 2012;25:9–15. doi: 10.1007/s13577-011-0038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P, Somasundaram K, Krishna S. Activated Notch1 inhibits p53-induced apoptosis and sustains transformation by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 oncogenes through a PI3K-PKB/Akt-dependent pathway. J Virol. 2003;77:7106–7112. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7106-7112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nefedova Y, Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and clinical prospects of Notch inhibitors in the therapy of hematological malignancies. Drug Resist Updat. 2008;11:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PH, Giraud J, Staedel C, Chambonnier L, Dubus P, Chevret E, Bœuf H, Gauthereau X, Rousseau B, Fevre M, Soubeyran I, Belleannée G, Evrard S, Collet D, Mégraud F, Varon C. All-trans retinoic acid targets gastric cancer stem cells and inhibits patient-derived gastric carcinoma tumor growth. Oncogene. 2016;35:5619–5628. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niapour N, Mohammadi-Ghalehbin B, Golmohammadi MG, Gholami MR, Amani M, Niapour A. An efficient system for selection and culture of Schwann cells from adult rat peripheral nerves. Cytotechnology. 2016;68:629–636. doi: 10.1007/s10616-014-9810-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niapour N, Shokri S, Amani M, Sharifi Pasandi M, Salehi H, Niapour A. Effects of all trans retinoic acid on apoptosis induction and notch1, hes1 genes expression in gastric cancer cell line MKN-45. Koomesh. 2016;17:1024–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell CS, Radtke F. Notch as a tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:145–159. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannuti A, Foreman K, Rizzo P, Osipo C, Golde T, Osborne B, Miele L. Targeting Notch to target cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3141–3152. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazzi G, Fini L, Selgrad M, Garcia M, Daoud Y, Wex T, Malfertheiner P, Gasbarrini A, Romano M, Meyer RL, Genta RM, Fox JG, Boland CR, Bazzoli F, Ricciardiello L. Epigenetic regulation of Delta-Like1 controls Notch1 activation in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2011;2:1291–1301. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain S, Lacomme S, Battaglia-Hsu SF, du Manoir S, Brochin L, Vignaud JM, Martinet N. Signalling with retinoids in the human lung: validation of new tools for the expression study of retinoid receptors. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:423. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme I, Saavedra K, Espinoza JA, Weber H, García P, Nervi B, Garrido M, Corvalán AH, Roa JC, Bizama C. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: towards a pathway-driven targeted therapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24750–24779. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethi N, Kang Y. Notch signalling in cancer progression and bone metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1805–1810. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi Pasandi M, Hosseini Shirazi F, Gholami MR, Salehi H, Najafzadeh N, Mazani M, Ghasemi Hamidabadi H, Niapour A. Epi/perineural and Schwann cells as well as perineural sheath integrity are affected following 2,4-d exposure. Neurotox Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12640-017-9777-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Ie M, Wang TL. Notch signaling, gamma-secretase inhibitors, and cancer therapy. Can Res. 2007;67:1879–1882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su F, Zhu S, Ruan J, Muftuoglu Y, Zhang L, Yuan Q. Combination therapy of RY10-4 with the gamma-secretase inhibitor DAPT shows promise in treating HER2-amplified breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:4142–4154. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vauclair S, Majo F, Durham AD, Ghyselinck NB, Barrandon Y, Radtke F. Corneal epithelial cell fate is maintained during repair by Notch1 signaling via the regulation of vitamin A metabolism. Dev Cell. 2007;13:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Li Y, Banerjee S, Sarkar FH. Exploitation of the Notch signaling pathway as a novel target for cancer therapy. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:3621–3630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Li Y, Sarkar FH. Notch signaling proteins: legitimate targets for cancer therapy. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11:398–408. doi: 10.2174/138920310791824039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Stutzman A, Mo YY. Notch signaling and its role in breast cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4370–4383. doi: 10.2741/2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan B, Liu L, Zhao Y, Xiu LJ, Sun DZ, Liu X, Liu Y, Shi J, Zhang YC, Li YJ, Wang XW, Zhou YQ, Feng SH, Lv C, Wei PK, Qin ZF. Xiaotan Sanjie decoction attenuates tumor angiogenesis by manipulating Notch-1-regulated proliferation of gastric cancer stem-like cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13105–13118. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i36.13105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Qian C, Shu T, Zhang X, Zhao Z, Liang Y. Combination treatment of PD98059 and DAPT in gastric cancer through induction of apoptosis and downregulation of WNT/beta-catenin. Cancer Biol Ther. 2013;14:833–839. doi: 10.4161/cbt.25332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying M, Wang S, Sang Y, Sun P, Lal B, Goodwin CR, Guerrero-Cazares H, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Laterra J, Xia S. Regulation of glioblastoma stem cells by retinoic acid: role for Notch pathway inhibition. Oncogene. 2011;30:3454–3467. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Wu H, Xu H, Xiong H, Chu Q, Yu S, Wu GS, Wu K. Notch signaling: an emerging therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Cancer Lett. 2015;369:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti A, Affatato R, Centritto F, Fratelli M, Kurosaki M, Barzago MM, Bolis M, Terao M, Garattini E, Paroni G. All-trans-retinoic acid modulates the plasticity and inhibits the motility of breast cancer cells: ROLE OF NOTCH1 AND TRANSFORMING GROWTH FACTOR (TGFbeta) J Biol Chem. 2015;290:17690–17709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.638510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JP, Chen XY, Li JS. Effects of all-trans-retinoic on human gastric cancer cells BGC-823. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZL, Zhang L, Huang CF, Ma SR, Bu LL, Liu JF, Yu GT, Liu B, Gutkind JS, Kulkarni AB, Zhang WF, Sun ZJ. NOTCH1 inhibition enhances the efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents by targeting head neck cancer stem cell. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24704. doi: 10.1038/srep24704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]