Abstract

During mammalian heart development, restricted myocardial Bmp2 expression is a key patterning signal for atrioventricular canal specification and the epithelial–mesenchyme transition that gives rise to the valves. Using a mouse transgenic line conditionally expressing Bmp2, we show that widespread Bmp2 expression in the myocardium leads to valve and chamber dysmorphogenesis and embryonic death by E15.5. Transgenic embryos show thickened valves, ventricular septal defect, enlarged trabeculae and dilated ventricles, with an endocardium able to undergo EMT both in vivo and in vitro. Gene profiling and marker analysis indicate that cellular proliferation is increased in transgenic embryos, whereas chamber maturation and patterning are impaired. Similarly, forced Bmp2 expression stimulates proliferation and blocks cardiomyocyte differentiation of embryoid bodies. These data show that widespread myocardial Bmp2 expression directs ectopic valve primordium formation and maintains ventricular myocardium and cardiac progenitors in a primitive, proliferative state, identifying the potential of Bmp2 in the expansion of immature cardiomyocytes.

Introduction

Formation of the primitive cardiac valves begins at E9.5 in mice, when signals from the atrioventricular canal (AVC) myocardium stimulate the adjacent endocardial cells to undergo an epithelial–mesenchyme transition (EMT) and form the valves primordia. This process is patterned and only AVC endocardial cells are competent to respond to these signals and initiate EMT1. Studies in mice have revealed the genetic network controlling AVC myocardium patterning, including the T-box transcription factors Tbx2 and Tbx3, which repress chamber-specific gene expression in AVC2,3 and Tbx20, which restricts Tbx2 expression to the AVC in a Smad-dependent manner4.

Bmp2 (bone morphogenetic protein 2) a transforming growth factor beta (Tgfβ) superfamily member, expressed in AVC myocardium, is sufficient for AVC specification and EMT induction5–8. Bmp2 controls AVC myocardial patterning via Tbx2 activation9, and attenuates AVC myocardial proliferation via n-Myc repression10. Temporal control of BMP2 signalling is crucial for cardiomyocyte differentiation from mouse ES cells (mESC) in vitro. Thus, inhibition of BMP2 signalling before embryoid body (EB) formation, or in mesoderm-committed (Brachyury-T positive) EBs, induces cardiomyogenesis11.

We asked whether Bmp2 is able to specify a prospective ventricle as AVC, and what is the effect of Bmp2 on chamber cardiomyocytes. We have generated a transgenic line conditionally expressing Bmp2 and examined the consequences of ectopic Bmp2 expression in heart development. Nkx2.5Cre-driven Bmp2 myocardial overexpression leads to embryonic death at E15.5, and rescues the AVC specification defect of Bmp2-null embryos. E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos show enlarged valves and trabeculae, dilated ventricles and ventricular septal defect. Remarkably, transgenic ventricular endocardium is EMT-competent both in vivo and in vitro. Gene profile and marker analysis of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts indicated that cardiac cellular proliferation is increased, and while chamber myocardium gene expression is maintained, its maturation is blocked. We obtained similar results using a second myocardial driver (cTnTCre), but not with an endothelial-specific driver (Tie2Cre), suggesting that Bmp2 needs to reach a certain threshold to drive EMT and prevent cardiomyocyte maturation. Accordingly, forced Bmp2 expression in vitro stimulated EBs proliferation and blocked their progression into cardiomyogenesis, an effect partially rescued by Noggin. These data demonstrate that Bmp2 is an instructive signal for valve formation and that persistent Bmp2 expression maintains cardiomyocytes in a primitive, proliferative state, which may be relevant for the in vitro expansion of cardiac progenitors for regenerative purposes.

Results

Ectopic myocardial Bmp2 expression disrupts heart morphogenesis

To study the developmental consequences of Bmp2 expression outside of the valve forming field, we generated a transgenic line in which Bmp2 expression is activated upon Cre-mediated removal of a β-Geo-stop cassette (Suppl. Figure S1A and Materials and methods).

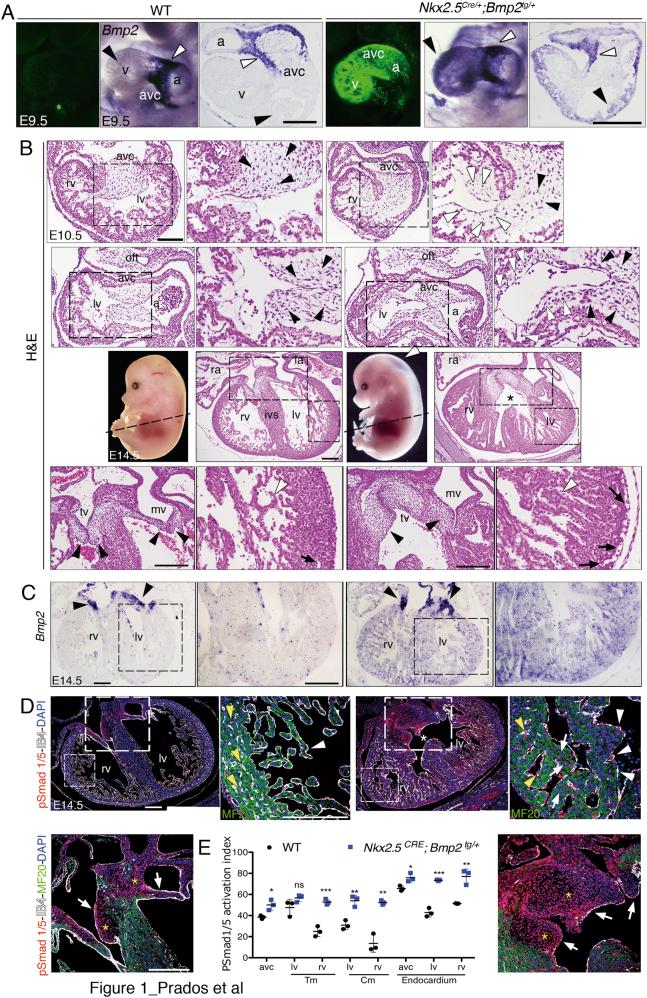

We expressed Bmp2 in the developing myocardium using the Nkx2.5Cre line, active since E7.512. At E9.5, transgenic hearts showed widespread GFP expression (Fig. 1a and Suppl. Figure S1A). Whole-mount in situ hybridisation (WISH) showed that Bmp2 transcription was restricted to AVC myocardium in E9.5 wild type (WT) embryos (Fig. 1a and ref. 7), whereas Nkx2.5Cre-driven Bmp2 expression in transgenic embryos was expanded to chamber myocardium (Fig. 1a). Histological analysis of E9.5 WT embryos revealed mesenchyme in AVC cushions and developing ventricular trabeculae (Suppl. Figure S1B). On the contrary, Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos showed abundant mesenchyme in AVC cushions but also in subendocardium of the right ventricle (Suppl. Figure S1B). This phenotype was more evident at E10.5, when subendocardial mesenchymal cells were observed in AVC and in both ventricles (Fig. 1b). Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts showed thickened ventricular trabeculae at E12.5 (Suppl. Figure S1B) and at E14.5, embryos were oedematous (Fig. 1b) suggesting cardiovascular deficit. Histological inspection of E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts showed mesenchyme in all the forming valve leaflets, ventricular septal defect, dilated ventricles and coronary vessels, and large trabeculae (Fig. 1b and Suppl. Figure S1B). Transmission electron microscopy revealed denser packing of cardiomyocytes within the trabeculae of E14.5 Nkx2.5CRE/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Suppl. Figure S1C, D), as well as poorly defined Z band structure (Suppl. Figure S1C′, C″ versus S1D′, D″), suggesting defective cardiomyocyte maturation.

Fig. 1. Ectopic myocardial Bmp2 expression disrupts cardiogenesis.

a Confocal images of GFP expression plus whole-mount and sectioned in situ hybridisation (ISH) of Bmp2 in E9.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts. White arrowheads mark normal Bmp2 expression in AVC myocardium; black arrowheads mark ectopic Bmp2 expression in chamber myocardium of the transgenic heart. b Top two rows, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of general and detailed views (insets) of transverse and parasagittal sections of E10.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts, showing mesenchymal cells in the AVC (black arrowheads) and also in the left ventricles of transgenic hearts (white arrowheads). Third row, whole-mount images of E14.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos showing oedema in the dorsal region of the transgenic embryo (white arrowhead). H&E stained transverse sections show general and detailed views of ventricular and valve dysmorphology and a ventricular septal defect in the E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ heart (asterisk). Fourth row, details of the atrioventricular (AV) valves (arrowheads) and left ventricle in the WT and transgenic heart; trabeculae (white arrowheads) are larger in the transgenic heart. The arrows mark the WT coronary vessels and the dysmorphic ones in the transgenic heart. c ISH showing Bmp2 mRNA in the AV valves in both E14.5 genotypes (arrowheads) and ectopically throughout the myocardium of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ ventricles. d Staining for pSmad 1/5 (red), MF 20 (green), isolectin B4 (IB4, white) and DAPI (blue) in E14.5 hearts. General views of transverse heart sections. Note the ventricular septal defect (asterisk) in the transgenic heart. Detailed views show the right ventricle and AV valves of both genotypes, with discrete pSmad 1/5 staining in WT trabecular endocardium (white arrowheads), capillaries in the compact myocardium (yellow arrowheads) and AV valves mesenchyme (arrows, mesenchyme marked with a yellow asterisk). The Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ heart shows widespread pSmad1/5 expression both in ventricles (including cardiomyocytes, arrows) and in AV valves mesenchyme. e pSmad1/5 activation index in the trabecular and compact myocardium (Tm, Cm) of E14.5 WT and transgenic hearts. a atrium, AVC atrioventricular canal, IVS interventricular septum, la left atrium, lv left ventricle, mv mitral valve, ra right atrium, rv right ventricle, tv tricuspid valve, v ventricle; scale bars 200 μm

At E14.5, in situ hybridisation (ISH) showed that Bmp2 mRNA was restricted to the myocardium of WT AVC (Fig. 1c), whereas in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts, Bmp2 expression was stronger in AVC myocardium and was extended to ventricular myocardium (Fig. 1c). We did not recover alive Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos beyond E15.5 (Supplemental Table S1). Expression of the phosphorylated Bmp2 signalling effector transcription factors Smad1 and 5 (pSmad1/5)13 was moderate in E14.5 WT ventricular endocardium and myocardium, while pSmad1/5 was widely expressed throughout Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts (Fig. 1d, e). These results demonstrated that Nkx2.5Cre-mediated ectopic Bmp2 expression leads to increased Bmp signalling activity in the myocardium, endocardium and valve mesenchyme.

Myocardial Bmp2 expression rescues AVC specification in Bmp2-deficient mice

qPCR analysis showed that Bmp2 expression was moderately elevated in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts (Suppl. Figure S2A), prompting us to test whether Nkx2.5-Cre-mediated Bmp2 expression could rescue the AVC specification defect of Bmp2 mutants. Whole-mount and histological analyses showed that Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+;Bmp2flox/flox embryos had a well-defined AVC comparable to that of control Bmp2flox/flox mice (Suppl. Figure S2B), indicating effective rescue of the AVC specification defect of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2flox/flox mutants. Bmp2 was expressed in AVC of control, Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+;Bmp2flox/flox and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos, but not in Nkx2.5Cre;Bmp2flox/flox embryos (Suppl. Figure S2B). Nkx2.5Cre;Bmp2flox/flox embryos do not survive beyond E11.57,14, whereas rescued embryos were still alive at E14.5, with defective ventricle and valve development (Suppl. Figure S2C). We found no live Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+;Bmp2flox/flox embryos beyond E15.5 (Supplemental F S2). These results showed that myocardial expression of Bmp2 rescues AVC specification of Bmp2-deficient mice but leads to lethality at E15.5.

Ectopic myocardial Bmp2 expression renders the ventricles EMT-competent

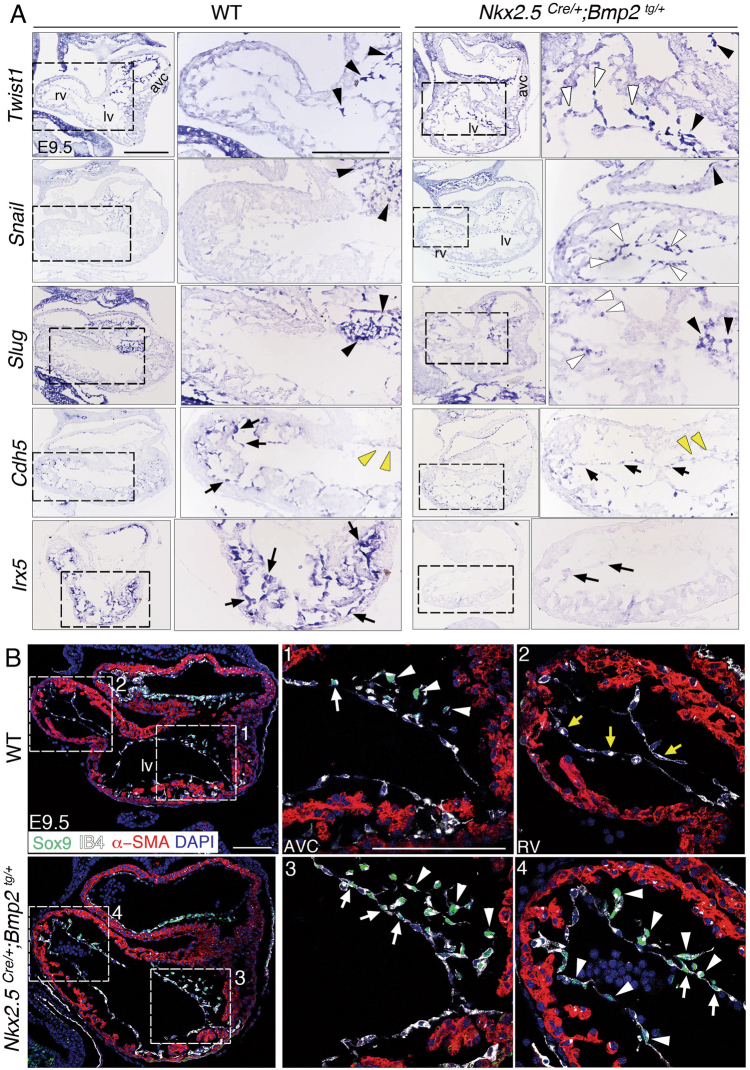

The cardiac EMT drivers Twist17, Snail15 and Slug16 are transcribed in the WT AVC endocardium and mesenchyme, and their expression was expanded to the ventricles in E9.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 2a). Snail represses vascular endothelial cadherin (Cdh5) expression in E9.5 AVC endocardium so that EMT occurs15. ISH confirmed absence of Cdh5 expression in WT AVC endocardium, and strong expression in ventricular endocardium (Fig. 2a). In contrast, E9.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos showed weaker and discontinuous Cdh5 expression in ventricular endocardium (Fig. 2a). E9.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos also had severely reduced expression of the chamber endocardium marker Irx517 (Fig. 2a), indicating loss of chamber endocardium identity. qPCR analysis confirmed the increased expression of the EMT drivers Tgfβ2, Snail1 and Twist1 in E9.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts (Suppl. Figure S2D). We also immunostained E9.5 embryos with Sox9, a well-known Bmp2 target in EMT7,18, isolectin B4 (IB4) to label the endocardium and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) to mark the myocardium. In the E9.5 WT heart, Sox9 is expressed in AVC mesenchymal cells (Fig. 2b-1, 2), whereas in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos Sox9 is expressed in AVC endocardium and mesenchyme, but also in ventricular endocardium (and derived mesenchymal cells, Fig. 2b-3, 4). These observations indicate that myocardial Bmp2 expression leads to ectopic EMT drivers activation, that will induce transformation in ventricular endocardial cells.

Fig. 2. Expanded expression of the EMT drivers Twist1, Snail, Slug and Sox9, and reduction of Cdh5 and Irx5 expression in the ventricles of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos.

a ISH showing Twist1, Snail, Slug, Cdh5 and Irx5 mRNA in E9.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts. Black and yellow arrowheads mark expression or lack of expression in AVC mesenchyme cells, respectively; white arrowheads indicate expression in chamber endocardium. Cdh5 and Irx5 are transcribed in WT chamber endocardium, while are strongly reduced in the transgenic ventricle (black arrows). Scale bars 200 μm. b Confocal images of E9.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts stained with Sox9 (green), IB4 (white), α-SMA (red) and DAPI (blue). Mesenchyme (1, arrowheads) and endocardial cells (1, arrow) in the WT AVC express Sox9, while IB4-positive endocardial cells of the right ventricle do not (2, yellow arrows). Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts show Sox9-positive mesenchyme (3, arrowheads) and endocardial cells (3, arrows) in AVC, but also in the right ventricle (4, arrowheads and arrows). Scale bars 100 μm. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1

At E14.5, these EMT markers were still upregulated (Suppl. Figure 2A) although expression was confined to the enlarged valves (Suppl. Figure S3A).

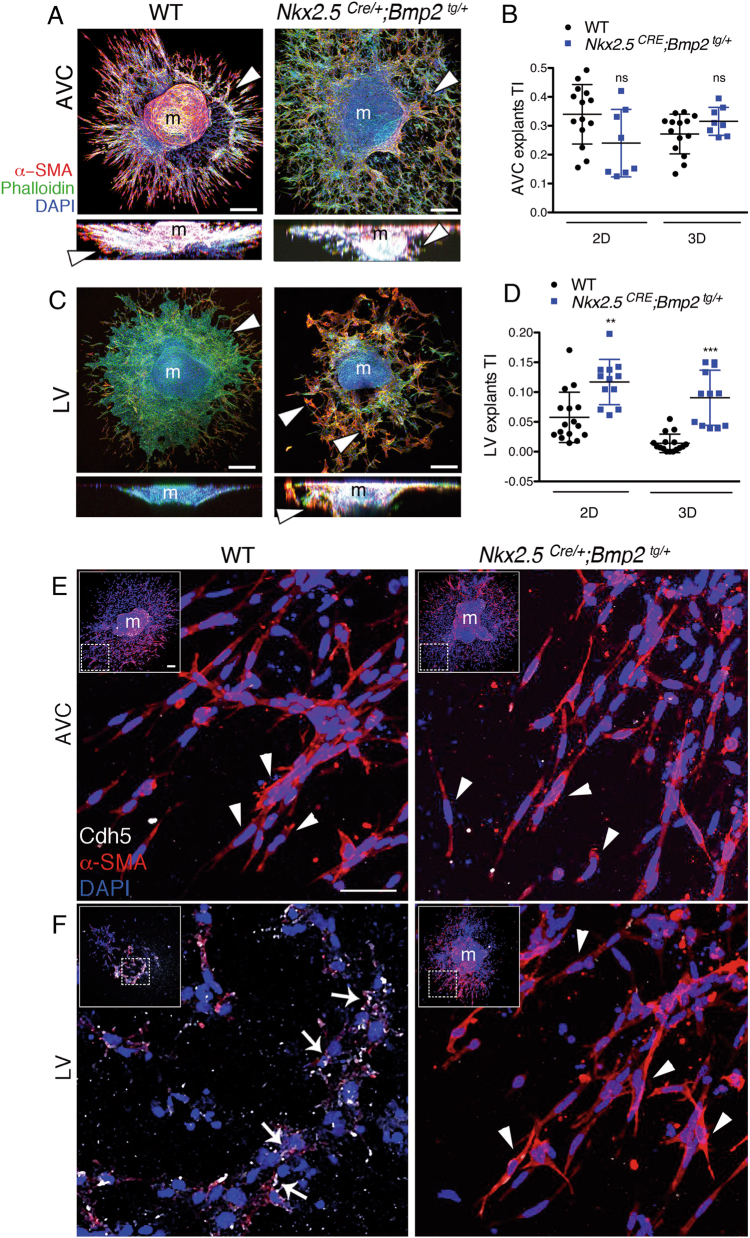

We assayed in explants the ability of myocardial Bmp2 to induce ectopic EMT. We first explanted AVC tissue from WT and transgenic hearts as described1,15 and measured the two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) transformation index (TI), which define the migratory and invasive capacity of the explants, respectively19. E9.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ AVC explants generated mesenchymal cells invading the collagen gel (Fig. 3a). The 2D and 3D TI values were similar for both genotypes (Fig. 3a, b). Then, we carried out explants with the left ventricle. Cultures from WT ventricles generated a coherent endocardial monolayer surrounding the myocardium (Fig. 3c). In contrast, Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ ventricular explants gave rise to mesenchymal cells that invaded the collagen matrix, similarly to control AVC explants (Fig. 3c, d). These ventricular endocardium-transformed mesenchymal cells had a significantly higher 2D TI and 3D TI than WT explants (Fig. 3c, d). We stained with anti-Cdh5 and α-SMA antibodies, to label the various cell types in the explants15. Figure 3e shows that transformed mesenchymal cells in both WT and transgenic AVC explants stain with α-SMA, but not with anti-Cdh5. Endocardial cells of WT ventricular explants, that do not transform (Fig. 3c, d), express Cdh5 and do not express α-SMA (Fig. 3f, left). In contrast, transformed mesenchymal cells of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ ventricular explants express α-SMA, but not Cdh5 (Fig. 3f, right).

Fig. 3. The AVC and ventricles of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos undergo EMT in vitro.

a Confocal images of AVC explants from E9.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts cultured on collagen gels (top and lateral projections). All explants were stained with phalloidin-FITC (green), anti-α-SMA-Cy3 (red) and DAPI (blue). AVC mesenchymal cells (α-SMA-positive) invade the collagen gel (arrowheads). b Quantification of migrating (2D, endocardial) and invading (3D, mesenchyme) cells in WT and transgenic AVC explants. c Confocal images of stained left ventricular explants (LV). WT LV endocardial cells do not undergo EMT and form a monolayer on the surface of the gel (arrowhead). Transgenic LV endocardial cells transform, migrate and invade the collagen gel (arrowheads in top views and lateral projections). d Quantification of migrating and invading cells in LV explants shows a significantly higher 2D and 3D transformation indexes (TI) in transgenic explants than in WT. TI is the number of migrating (2D) or invading (3D) cells divided by the total number of cells in each explant. m myocardium. t test ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005. e, f Confocal images of explants. e The insets show general views of WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ AVC explants stained with anti-Cdh5 (white), anti-α-SMA (red) and DAPI (blue). The large images are a magnification of the area marked in the insets and show mesenchymal cells stained with anti-α-SMA and DAPI, but not with anti-Cdh5 (arrowheads). f The insets show general views of WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ ventricular explants stained with the same antibodies than above (in the WT ventricular explant the myocardium (m) has been removed). The large images are a magnification of the area marked in the insets and show that WT ventricular endocardial cells express Cdh5 (F, white arrows), while transformed mesenchymal cells in transgenic ventricular explants express α-SMA (F, arrowheads). Scale bars 100 μm in insets; 50 μm in large images

Myocardial Bmp2 gain-of-function stimulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and prevents chamber maturation

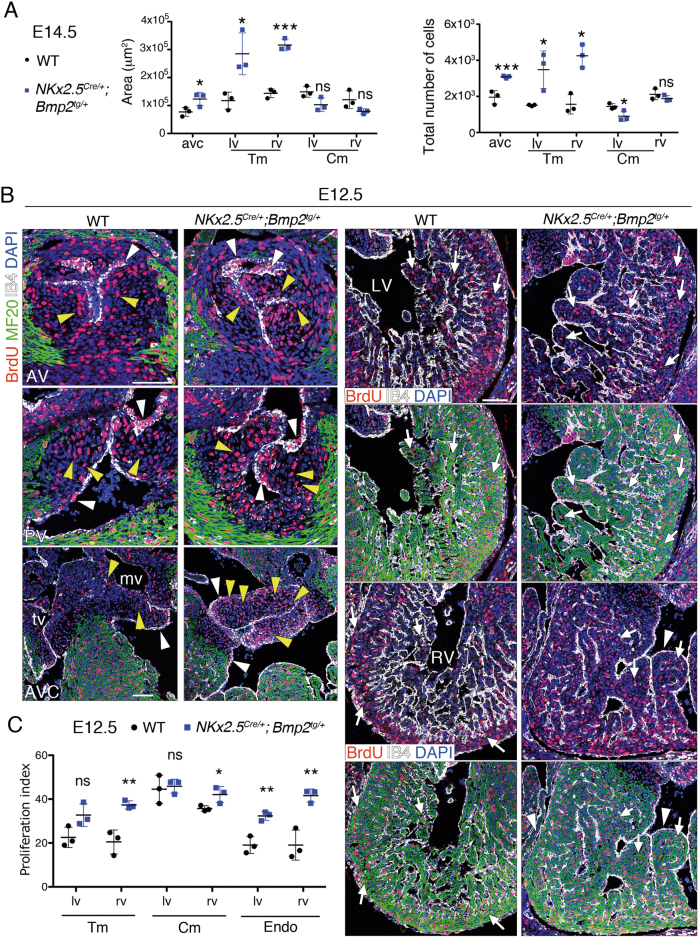

The enlarged trabeculae and valves in E14.5, Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 1b) prompted us to measure the surface of the myocardium and AVC, and their total number of cells. The compact myocardium area was similar in WT and transgenic embryos, whereas the trabecular myocardium and AVC regions were larger and contained more cells in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos show increased cardiac proliferation.

a Area occupied by the various cardiac territories, and the total number of cells within them, analysed in E14.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts. b Proliferation analysis in E12.5 WT and transgenic heart sections. Sections are stained with an anti-BrdU (red) and anti-MF20 (green, myocardium) antibodies, isolectin B4 (white, endocardium) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). AV aortic valve, AVC atrioventricular valves, LV left ventricle, mv mitral valve, RV right ventricle, tv tricuspid valve. The top rows in the column corresponding to the sections of the ventricles show only anti-BrdU, IB4 and DAPI staining, to facilitate identification of BrdU-positive nuclei. The white and yellow arrowheads indicate BrdU-positive endocardium or mesenchyme nuclei, respectively. The white arrows indicate BrdU-positive nuclei in myocardium. Scale bars 200 μm. c Proliferation index in E12.5 WT and transgenic hearts is the ratio of BrdU-positive nuclei to the total number of nuclei in each cell type. t test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ns non-significant

We examined cell proliferation by measuring 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation in WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ E12.5 hearts. We observed a significantly increased proliferation in AVC valves mesenchyme, but not in aortic or pulmonary valves of transgenic hearts (Suppl. Figure S3C and Fig. 4b). Proliferation was also increased in compact and trabecular myocardium of the right ventricle, and throughout ventricular endocardium (Fig. 4b, c). This elevated proliferation was sustained but less pronounced at E14.5 (Suppl. Figure S3B, C). Thus, Bmp2 overexpression in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos leads to a proliferative expansion of valves and trabeculae.

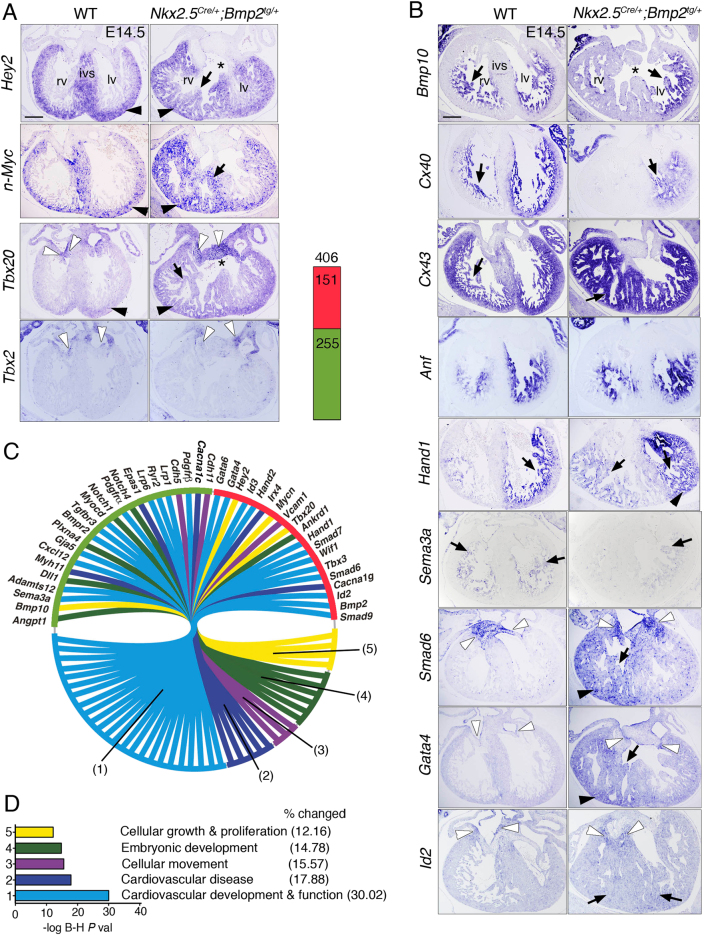

The compact myocardium markers Hey220 and n-Myc21 were expanded to trabecular myocardium at E14.5 (Fig. 5a), suggesting impaired chamber maturation in transgenic embryos. Likewise, Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos showed increased Tbx20 expression in AVC valves and expansion to the trabeculae (Fig. 5a). In contrast, Tbx2 was normally expressed in AVC valves (Fig. 5a). These results are in accordance with the reported repression of Tbx2 by Hey2 and Tbx20 in chamber myocardium, resulting in AVC-restricted Tbx2 expression10,22. Tbx20 interacts with Bmp/Smad signalling to confine Tbx2 expression to the AVC23.

Fig. 5. Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos show defective ventricular chamber maturation.

a E14.5, ISH. The black arrowheads mark compact myocardium, arrows mark trabeculae, white arrowheads the AVC valves region and the asterisks indicate a ventricular septal defect. ISH of Hey2, n-Myc, Tbx20 and Tbx2 in E14.5 WT and Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts. b ISH of Bmp10, Cx40, Cx43, Anf, Hand1, Sema3a, Smad6, Gata4 and Id2 in E14.5 WT and transgenic hearts. IVS interventricular septum, rv right ventricle, lv left ventricle. Scale bars 200 μm. c Left, Circular plot of 42 differentially expressed genes in E14.5 transgenic hearts. Top, Chart showing the total number of upregulated (red) and downregulated genes (green). Details are available in Supplementary file 1. d B-H P value, Benjamini–Hochberg-adjusted P value. % changed classifies the genes altered in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ transgenic hearts as a percentage of the total number of genes involved in the listed biological function. t test *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005

The trabecular markers Bmp1024 and Cx40/Gja525 were downregulated in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 5b), while Cx43 was upregulated and Anf unaffected (Fig. 5b). The transcription factor Hand1, a Tbx20 effector26,27 was upregulated and extended to the right ventricle of transgenic embryos (Fig. 5b). These results, together with the expansion of the compact myocardium markers (Fig. 5a), and the increased cardiomyocyte proliferation in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 4b, c and Suppl. Figure S3B, C), indicate that ectopic myocardial Bmp2 expression disrupts ventricular chamber maturation by promoting proliferation and preventing cardiomyocyte differentiation.

Gene profiling reveals dysregulated cardiovascular development and cellular proliferation

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) identified altered cardiac expression of 406 genes (P ≤ 0.05) in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts, 151 genes were upregulated and 255 downregulated (Fig. 5c and Suppl. File S1). Confirming our ISH analysis, Bmp2, Tbx20, n-Myc, Hey2, Hand1 and Hand2 were upregulated, whereas Cx40 and Bmp10 were downregulated (Fig. 5c and Suppl. File S1). Gene ontology (GO) classification revealed that most dysregulated genes in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts were involved in cardiac development and disease, and cell growth and proliferation (Fig. 5c, d and Supplemental File 1). Genes implicated in coronary vessel formation (Hey1, Dll4, Epas1, Sema3a, Angpt1) were also downregulated (Fig. 5c). ISH for the coronary artery markers Dll4, Hey1, Cxcr4 and Fabp428 confirmed these data (Fig. 5b and Suppl. Figure S4A–H). The number of Fabp4-positive vessels was reduced in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Suppl. Figure S4I), indicating defective coronary vessel development.

Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos also showed increased Smad6 and Smad7 expression (Fig. 5c), which encode inhibitory Smads29. Smad6 was ectopically expressed in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ ventricles (Fig. 5b), presumably reflecting a negative-feedback loop triggered by ectopic Bmp2 expression, as in vitro experiments suggested30. Similarly, the cardiac specification marker Gata431 was upregulated in myocardium, especially of the right ventricle in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos, and in AVC valves endocardium (Fig. 5b). RNA-seq (Fig. 5c) and qPCR data (Suppl. Figure S2A) showed upregulation of Id2, a n-Myc effector critical for cell proliferation32. n-Myc is a direct downstream target of Smad433. In addition, both Hey2 and n-Myc are required for cardiomyocyte proliferation20,34, suggesting that the increased cardiac proliferation observed in Nkx2.5CRE/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos (Fig. 4b, c) could be mediated by Hey2, n-Myc and Id2 activation downstream of Bmp2.

Bmp2 gain-of-function in myocardium, but not endothelium, disrupts ventricular development

We used the myocardial-specific cTnT-Cre line, active from E8.0 onwards35, that caused a phenotype similar to Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos. E10.5 cTnTCre/+;Bmp2tg/+ mice showed enlarged AVC, and mesenchymal cells in the right ventricle (Suppl. Figure S5A). E14.5 cTnTCre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos had ventricular septal defect, dilated ventricles and coronaries, and thickened valves and trabeculae (Suppl. Figure S5B), and did not progress beyond E17.5 (Supplemental Table S3). cTnTCre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts expressed Bmp2 throughout the myocardium (Suppl. Figure S5B). These embryos showed upregulated Tbx20 expression (Suppl. Figure S5C), expansion of Hey2 to the trabeculae (Suppl. Figure S5C) and reduced Cx40 and Bmp10 expression (Suppl. Figure S5D), indicating impaired ventricular chamber maturation. Coronary vessels were also affected, as the loss of Cx40 expression indicated (Suppl. Figure S5D). Tbx2 and Cx43/Gja1 expression was unaltered (Suppl. Figure S5D).

Myocardium-derived Bmp2 binds to its receptor in AVC endocardium to activate EMT7. We used the Tie2Cre driver to express Bmp2 in vascular endothelium and endocardium from E7.536. E10.5 Tie2Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos had normal heart morphology (Suppl. Figure S5E and data not shown). Indeed, Tie2Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos developed normally and reached adulthood (Supplemental Table S4). qPCR showed a slight increase in Bmp2 transcription and normal Twist1, Snail, Cdh5 and Slug expression in E14.5 transgenic embryos (Suppl. Figure S6A). These results indicate that Tie2-Cre-mediated ectopic Bmp2 expression does not affect cardiogenesis, and indicate that the phenotypic similarities between Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ and cTnTCre/+;Bmp2tg/+ mice are due to myocardial Bmp2 overexpression.

Bmp2 stimulates proliferation and prevents cardiomyogenesis in vitro

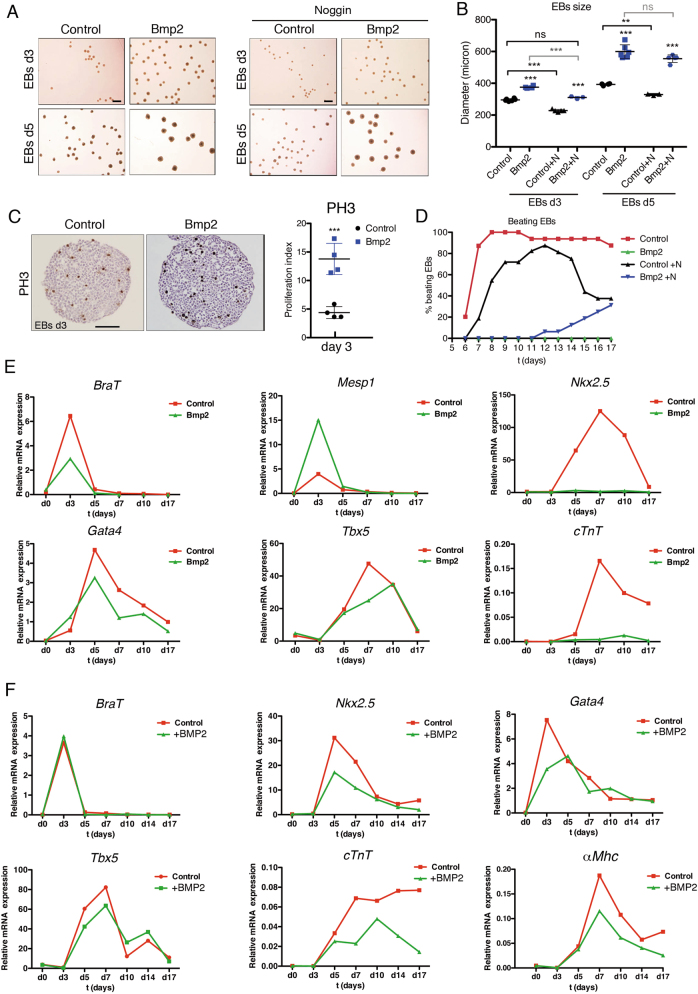

The increased proliferation and impaired cardiomyocyte maturation of Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ mice prompted us to test the ability of R26CAGBmp2-eGFP mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) to form embryoid bodies (EBs) and differentiate into cardiomyocytes37. R26CAGBmp2-eGFP mESCs were transfected with a Cre-expressing plasmid, and GFP-positive clones (Bmp2-mESCs) were identified (Suppl. Figure S6B). Non-recombined clones were used as control mESCs. ELISA revealed around 3.5-fold Bmp2 increase in the culture medium of Bmp2-ESCs (Suppl. Figure S6C). Bmp2-expressing embryoid bodies (Bmp2-EBs) expressed GFP, whether cultured in suspension or plated (Suppl. Figure S6D). Bmp2-EBs at day 3 (d3) and d5 of culture were larger than control EBs (Fig. 6a, b). To determine whether this size difference was due to Bmp2 overexpression, we cultured EBs with different concentrations (see Experimental procedures) of the Bmp antagonist Noggin38. Overall, 500 ng/ml Noggin had an effect on Bmp2-EBs, being added from 3 days before EBs formation (d-3) to day 17 (d17). Noggin reduced the size of control and Bmp2-EBs at d3 (Fig. 6a,b) and prevented Bmp2-EBs from growing more than control EBs (Fig. 6a, b). By d5, Noggin was unable to reduce the size of Bmp2-EBs (Fig. 6a, b), but reduced the size of control EBs (Fig. 6a, b). Phospho-Histone3 (PH3) and BrdU analyses revealed markedly increased proliferation in Bmp2-EBs at d3 (Fig. 6c and Suppl. Figure S6E). These data indicate that Bmp2 overexpression in EBs promotes proliferation and that continuous Noggin-mediated Bmp2 blockade limits this effect.

Fig. 6. Constitutive Bmp2 expression leads to increased proliferation and blockade of cardiac differentiation in embryoid bodies (EBs).

a Images showing EBs size at day 3 (d3) and day 5 (d5) of culture. Bmp2-expressing-EBs (Bmp2) are visibly larger than controls. Noggin (500 ng/ml, right panels) reduced the size of both control and Bmp2-EBs at d3 but not the size of Bmp2-EBs at d5. Scale bars 1 mm. b Size quantification of the EBs shown in a (control, WT EBs; Bmp2, Bmp2-EBs;+N, Noggin-treated EBs). Bmp2-EBs were larger than WT EBs at d3 and d5 (Bmp2-EBs vs. Control EBs). Noggin significantly reduced the size of control and Bmp2-EBs at d3 but not of d5 Bmp2-EBs at d5 (treated EBs vs untreated EBs). Noggin-treated Bmp2-EBs were similar in size to untreated WT EBs at d3 but not at d5. ***P < 0.005, **P < 0.01, ns, non-significant one-way ANOVA (non-parametric) and Bonferroni post-test. c Phospho-Histone3 (PH3) staining in d3 control and Bmp2-EBs. Quantification shows a significant increase in PH3-positive nuclei. Scale bar 200 μm. t-test, ***P < 0.005. d Beating ability of WT EBs in the absence (red) or presence of Noggin (500 ng/ml) (black), or Bmp2-EBs in the absence (green) or presence of Noggin (blue). e, f Gene expression (qRT-PCR) of cardiac specification markers (BraT and Mesp1), early cardiac differentiation markers (Nkx2.5, Gata4, Tbx5 and cTnT) and late differentiation marker (αMhc) in e WT EBs (Control, red) and Bmp2-EBs (Bmp2, green) and f WT EBs (Control, red) and human recombinant BMP2-treated EBs (+BMP2, green)

We examined the beating ability of Bmp2-EBs from d6-d17 as an indication of cardiomyocyte differentiation37. Control EBs started beating at day 6, with more than 90% beating from d8-d17; in contrast, Bmp2-EBs did not beat at any time-point assayed (Fig. 6d). Noggin (500 ng/ml) partially restored beating ability in Bmp2-EBs 14 days after administration, with 30% of the culture beating by d17 (Fig. 6d). qPCR revealed an increase in Bmp2 and GFP expression in Bmp2-EBs (Suppl. Figure S6E). The d3 expression spike of the early mesodermal marker Brachyury (BraT)39 was suppressed in Bmp2-EBs, whereas the cardiac mesoderm marker Mesp140 was upregulated (Fig. 6e). The cardiac progenitor marker Nkx2.541 was undetectable, whereas the Gata4 and Tbx5 responses were decreased (Fig. 6e). Bmp2-EBs showed no detectable expression of the early cardiomyocyte differentiation marker cardiac Troponin T (cTnT) (Fig. 6e), and several late markers (Suppl. Figure S6F), suggesting that Bmp2-EBs do not progress to cardiomyogenesis. Similarly to the in vivo situation (Fig. 5b, c), Smad6 transcription was increased in Bmp2-EBs (Suppl. Figure S6F).

Our in vitro data show that constitutive Bmp2 overexpression in EBs affects cardiac differentiation. To test whether the increased BMP2 concentration affected cardiogenesis after cardiac specification had taken place, we cultured control R26CAG-Bmp2 mESCs in the presence or absence of human BMP2 (20 ng/ml) from d3 to d17. The beating ability of WT and BMP2-treated EBs was similar. qPCR on samples collected before and after BMP2 addition revealed no differences in BraT or Mesp1 expression between BMP2-treated and untreated EBs (Fig. 6f and Suppl. Figure S6G); however, BMP2 addition decreased the expression of early (Fig. 6f) and late cardiac differentiation markers (Suppl. Figure S6G). This result is consistent with our in vivo results and previous in vitro data11 suggesting that increased BMP2 signalling following cardiac mesoderm specification prevents cardiomyocyte differentiation.

Discussion

By activating Bmp2 expression throughout the embryonic myocardium, we provide genetic evidence indicating that Bmp2 is an instructive myocardial signal, able to induce the formation of cardiac valve primordia from AVC and non-AVC endocardial cells. Bmp2 gain in the embryonic myocardium promotes cardiac cell proliferation, disrupts valve remodelling and chamber cardiomyocyte patterning and maturation. Our data are informative about the mechanisms underlying mammalian cardiac patterning, and suggest that timely Bmp2 activation may be useful in the ex vivo expansion of immature cardiomyocytes.

Valve primordium formation, Bmp2 and endocardial competence

Explant assays with chicken AVC and ventricles showed that only AVC endocardium was able to undergo EMT1. Expression, explants and loss-of-function studies in mice confirmed that Bmp2 is crucial for AVC specification and cushion formation5–8. Our results show that myocardial Bmp2 gain directs ectopic EMT, expansion of EMT markers to ventricles and loss of chamber endocardial identity. Our data overturn the notion that only AVC endocardial cells are “competent” to respond to Bmp21, as ventricular endocardial cells also respond to Bmp2, upregulate EMT drivers and undergo full transformation. Thus, AVC endocardium competence to undergo EMT results from the tightly regulated AVC-restricted Bmp2 signalling, and not from the segregation of EMT-competent and non-competent endocardial cells in the early embryo.

The inability of forced endothelial-endocardial Bmp2 expression to trigger ectopic EMT, and the slight increase in Bmp2 transcription, suggests that Tie2Cre-driven Bmp2 levels might not reach a threshold required for promoting EMT outside the AVC. Our results show that forced myocardial Bmp2 expression promotes ectopic EMT, but does not alter the timing of valve primordium formation, as indicates the normal EMT drivers expression in the valves of E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos.

Bmp2 has been suggested to regulate AVC myocardial patterning through Tbx2 activation7. Hey2 and Tbx20 both directly repress Tbx2 in chamber myocardium, and confine its expression to the AVC through interaction with Bmp/Smad signalling10,22,23. Thus, the expanded expression of Hey2 and Tbx20 in E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos may explain why Tbx2 expression does not extend to the ventricles, despite being positively regulated by Bmp242. In addition, Bmp10 induces Tbx20 promoter activity in vitro through a conserved Smad1 binding site43. We hypothesise that the expanded Smad1/5 expression in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos could induce Tbx20 expression in a Smad-dependent manner, and thus repress Tbx2 in the chambers.

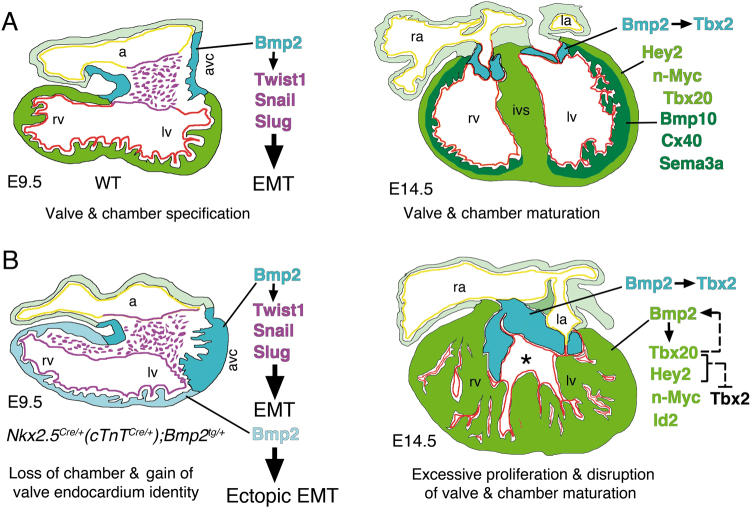

Proliferative and differentiation-inhibitory effects of Bmp2 gain in the myocardium

The increased cellular proliferation in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ hearts could seem paradoxical, since Bmp2 is normally expressed in the AVC, which is less proliferative than chamber myocardium44. Thus, one would expect that myocardial Bmp2 overexpression would attenuate cardiomyocyte proliferation. However, myocardial Bmp2 overexpression leads to increased and expanded expression of genes promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation, such as Hey2, n-Myc, Id2 and Tbx2020,21,32,33 (Fig. 7). Myocardial Bmp2 overexpression causes a phenotype similar to that caused by myocardial Tbx20 overexpression, which through BMP2/pSmad1/5/8 signalling promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and maintenance of embryonic characteristics in foetal and adult mouse hearts45,46. Therefore, the expanded Tbx20 expression in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos may reflect a positive feedback loop by which the expanded Smad1/5 expression in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos could induce Tbx20 expression throughout the heart. Smad4 inactivation with cTnTCre leads to a hypocellular myocardial wall, due to reduced ventricular cardiomyocyte proliferation. Expression of the Smad4 target n-Myc is downregulated in myocardial Smad4 mutants, as well as that of n-Myc target genes Cyclin D1, D2 and Id233. This negative effect of Bmp signalling loss on cardiomyocyte proliferation is compatible with our data showing the positive effect on cardiomyocyte proliferation of myocardial Bmp2 gain.

Fig. 7. Myocardial Bmp2 gain promotes ectopic EMT, stimulates cardiac proliferation and disrupts ventricular patterning and cardiomyocyte maturation.

a Left, E9.5 WT heart, chamber (ventricles and atria, green and light green) and non-chamber myocardium (AVC, blue) are specified. Bmp2 expression in AVC myocardium drives EMT via Twist1, Snail and Slug activation in AVC endocardium (purple). The Irx5-positive ventricular endocardium is coloured in red and the atrial endocardium in yellow. Right, E14.5 WT heart, the compacting ventricular myocardium is formed by an outer compact myocardium (Hey2-, n-Myc-positive, light green) and an inner trabecular myocardium (Bmp10-, Cx40-, Sema3a-positive, dark green). Tbx20 is expressed in compact and weakly, in trabecular myocardium. The maturing AVC valves (blue) express Bmp2 and Tbx2. B; left, E9.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+(or cTnTCre/+);Bmp2tg/+ transgenic heart. Bmp2 is normally expressed in AVC myocardium (blue) and ectopically in ventricular myocardium (light blue), driving Twist1, Snail and Slug expression in the Irx5-negative ventricular endocardium (purple), causing ectopic EMT. Right, E14.5 Nkx2.5Cre/+(or cTnTCre/+);Bmp2tg/+ transgenic heart. Bmp2 is expressed in an expanded AVC valve region (blue) and throughout the ventricles (green), leading to increased and expanded Tbx20, Hey2, n-Myc and Id2 expression in this tissue. As a consequence, cardiomyocyte proliferation is increased and chamber patterning/maturation is disrupted. The discontinuous arrow represents a potential positive feedback loop between Tbx20 and Bmp2 and the suggested negative regulation of Tbx2 by Tbx20 and Hey2. The asterisk indicates a ventricular septal defect. Abbreviations as in Fig. 1

Structural, marker and gene profiling analyses revealed that increased myocardial proliferation in Nkx2.5Cre/+;Bmp2tg/+ embryos is accompanied by defective ventricular chamber maturation, with an expansion of the more primitive and proliferative compact myocardium markers and the downregulation of trabecular markers (Fig. 7). These in vivo data were consistent with our in vitro EB differentiation results showing that constitutive Bmp2 expression stimulates EB proliferation, attenuates cardiac mesoderm specification and prevents cardiomyocyte differentiation. Defective maturation of Bmp2-EBs is reflected in the lack of beating ability, and reduced expression of Nkx2.5, Gata4 and Tbx5. Addition of BMP2 to the medium after cardiac specification did not affect EB beating but did impair cardiac differentiation. These observations are consistent with those showing that transient BMP signalling inhibition induces cardiomyocyte differentiation of mESC11. Thus, our data show that widespread myocardial Bmp2 expression maintains chamber myocardium and early cardiac progenitors in a primitive, proliferative state and identify Bmp2 as a potential factor for the expansion of cardiomyocytes in vitro. Studies in zebrafish show that bmp2b overexpression stimulates cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation and enhance cardiac regeneration47. Likewise, Tbx20 overexpression in adult cardiomyocytes promotes their proliferation and improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction through the activation of multiple pro-proliferation pathways, including BMP signalling48.

Materials and methods

Generation of R26CAGBmp2 transgenic line

See the supplemental experimental procedures.

Additional mouse lines

The following mouse strains were used: R26CAGBmp2tg (this report), Nkx2.5Cre12, cTnTCre35, Tie2Cre36 and BMP2flox49. For simplicity, R26CAGBmp2tg/+ is abbreviated in the text and figures as Bmp2tg/+. Details of genotyping will be provided upon request. Animal studies were approved by the CNIC Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee and by the Community of Madrid (Ref. PROEX 118/15). All animal procedures conformed to EU Directive 2010/63EU and Recommendation 2007/526/EC regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, enforced in Spanish law under Real Decreto 1201/2005.

ES cell culture, in vitro Cre recombination and EB differentiation

For details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Immunohistochemistry

For details about antibodies and protocols see supplemental experimental procedures.

Proliferation analysis and quantification on developing hearts

Cell proliferation in the developing heart was evaluated from BrdU incorporation50. For details see supplemental experimental procedures.

AVC and left ventricle explants

E9.5 WT and transgenic AVCs were harvested in sterile PBS. Left ventricles (lv) were carefully dissected, avoiding contamination with AVC tissue. Explants were placed on collagen gels with the endocardium face down6. For details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Explant culture quantification

For details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Confocal imaging

Confocal images of E9.5 whole-embryos, stained explants and tissue sections were acquired with a Nikon A1R laser scanning confocal microscope and NIS-Element SD Image Software. Images of stained explants were collected as z-stacks. Z-projections and lateral sections were assembled using ImageJ. Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop Creative Suit 5.1.

RNA-Seq

Hearts of E14.5 WT and Nkx2.5CRE/+; Bmp2tg/+ embryos (12 per genotype) were isolated on ice-cold PBS and the atria removed. Tissue was homogenised in Trizol (Invitrogen) using a Tissuelyzer (Qiagen). RNA was pooled into three replicates per genotype. For details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Accession number

Data are deposited in the NCBI GEO database under accession number GSE100810.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Grants SAF2016-78370-R, CB16/11/00399 (CIBER CV) and RD16/0011/0021 (TERCEL) from the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MEIC) and a grant from the Fundación BBVA (Ref.: BIO14_298) and Fundación La Marató (Ref.: 20153431) to J.L.d.l.P. J.M.P.-P. was supported by grant RD16/ 0011/ 0030 (Tercel). The cost of this publication was supported in part with FEDER funds. The CNIC is supported by the MEIC and the Pro-CNIC Foundation, and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (SEV-2015-0505).

Authors’ contributions

B.P., P.G.-A., T.P., G.L. and J.M.P.-P. performed experiments. B.P. and J.L.d.l.P. designed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. B.P., S.Z., J.M.P.-P. and J.L.d.l.P. reviewed the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript during its preparation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by A. Stephanou.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41419-018-0442-z).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Runyan RB, Markwald RR. Invasion of mesenchyme into three-dimensional collagen gels: a regional and temporal analysis of interaction in embryonic heart tissue. Dev. Biol. 1983;95:108–114. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aanhaanen WT, et al. The Tbx2+ primary myocardium of the atrioventricular canal forms the atrioventricular node and the base of the left ventricle. Circ. Res. 2009;104:1267–1274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.192450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesbah K, Harrelson Z, Theveniau-Ruissy M, Papaioannou VE, Kelly RG. Tbx3 is required for outflow tract development. Circ. Res. 2008;103:743–750. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh MK, et al. Tbx20 is essential for cardiac chamber differentiation and repression of Tbx2. Development. 2005;132:2697–2707. doi: 10.1242/dev.01854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugi Y, Yamamura H, Okagawa H, Markwald RR. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 can mediate myocardial regulation of atrioventricular cushion mesenchymal cell formation in mice. Dev. Biol. 2004;269:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luna-Zurita L, et al. Integration of a Notch-dependent mesenchymal gene program and Bmp2-driven cell invasiveness regulates murine cardiac valve formation. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;120:3493–3507. doi: 10.1172/JCI42666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma L, Lu MF, Schwartz RJ, Martin JF. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial–mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development. 2005;132:5601–5611. doi: 10.1242/dev.02156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivera-Feliciano J, Tabin CJ. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev. Biol. 2006;295:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada M, Revelli JP, Eichele G, Barron M, Schwartz RJ. Expression of chick Tbx-2, Tbx-3, and Tbx-5 genes during early heart development: evidence for BMP2 induction of Tbx2. Dev. Biol. 2000;228:95–105. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai CL, et al. T-box genes coordinate regional rates of proliferation and regional specification during cardiogenesis. Development. 2005;132:2475–2487. doi: 10.1242/dev.01832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuasa S, et al. Transient inhibition of BMP signaling by Noggin induces cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:607–611. doi: 10.1038/nbt1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanley EG, et al. Efficient Cre-mediated deletion in cardiac progenitor cells conferred by a 3’UTR-ires-Cre allele of the homeobox gene Nkx2-5. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002;46:431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katagiri, T. & Watabe, T. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.8, a021899 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rivera-Feliciano J, et al. Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development. 2006;133:3607–3618. doi: 10.1242/dev.02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmerman LA, et al. Notch promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition during cardiac development and oncogenic transformation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:99–115. doi: 10.1101/gad.276304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romano LA, Runyan RB. Slug is a mediator of epithelial–mesenchymal cell transformation in the developing chicken heart. Dev. Biol. 1999;212:243–254. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christoffels VM, Keijser AG, Houweling AC, Clout DE, Moorman AF. Patterning the embryonic heart: identification of five mouse Iroquois homeobox genes in the developing heart. Dev. Biol. 2000;224:263–274. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiyama H, et al. Essential role of Sox9 in the pathway that controls formation of cardiac valves and septa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6502–6507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401711101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luna-Zurita L, et al. Integration of a Notch-dependent mesenchymal gene program and Bmp2-driven cell invasiveness regulates murine cardiac valve formation. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3493–3507. doi: 10.1172/JCI42666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koibuchi N, Chin MT. CHF1/Hey2 plays a pivotal role in left ventricular maturation through suppression of ectopic atrial gene expression. Circ. Res. 2007;100:850–855. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261693.13269.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moens CB, Stanton BR, Parada LF, Rossant J. Defects in heart and lung development in compound heterozygotes for two different targeted mutations at the N-myc locus. Development. 1993;119:485–499. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.2.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokubo H, Tomita-Miyagawa S, Hamada Y, Saga Y. Hesr1 and Hesr2 regulate atrioventricular boundary formation in the developing heart through the repression of Tbx2. Development. 2007;134:747–755. doi: 10.1242/dev.02777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh R, et al. Tbx20 interacts with smads to confine tbx2 expression to the atrioventricular canal. Circ. Res. 2009;105:442–452. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, et al. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development. 2004;131:2219–2231. doi: 10.1242/dev.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Kempen MJ, et al. Developmental changes of connexin40 and connexin43 mRNA distribution patterns in the rat heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 1996;32:886–900. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(96)00131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai X, et al. Myocardial Tbx20 regulates early atrioventricular canal formation and endocardial epithelial–mesenchymal transition via Bmp2. Dev. Biol. 2011;360:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McFadden DG, et al. The Hand1 and Hand2 transcription factors regulate expansion of the embryonic cardiac ventricles in a gene dosage-dependent manner. Development. 2005;132:189–201. doi: 10.1242/dev.01562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He L, Tian X, Zhang H, Wythe JD, Zhou B. Fabp4-CreER lineage tracing reveals two distinctive coronary vascular populations. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2014;18:2152–2156. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyazawa K, Miyazono K. Regulation of TGF-beta Family Signaling by Inhibitory Smads. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017;9:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a022095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takase M, et al. Induction of Smad6 mRNA by bone morphogenetic proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;244:26–29. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo CT, et al. GATA4 transcription factor is required for ventral morphogenesis and heart tube formation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1048–1060. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lasorella A, et al. Id2 is critical for cellular proliferation and is the oncogenic effector of N-myc in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song L, et al. Myocardial smad4 is essential for cardiogenesis in mouse embryos. Circ. Res. 2007;101:277–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harmelink C, et al. Myocardial Mycn is essential for mouse ventricular wall morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2013;373:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiao K, et al. An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2362–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1124803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kisanuki YY, et al. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev. Biol. 2001;230:230–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boheler KR, Crider DG, Tarasova Y, Maltsev VA. Cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol. Med. 2005;108:417–435. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-850-1:417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim DA, et al. Noggin antagonizes BMP signaling to create a niche for adult neurogenesis. Neuron. 2000;28:713–726. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kispert A, Hermann BG. The Brachyury gene encodes a novel DNA binding protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:4898–4899. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saga Y, et al. MesP1: a novel basic helix-loop-helix protein expressed in the nascent mesodermal cells during mouse gastrulation. Development. 1996;122:2769–2778. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biben C, Harvey RP. Homeodomain factor Nkx2-5 controls left/right asymmetric expression of bHLH gene eHand during murine heart development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1357–1369. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shirai M, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Schneider MD, Schwartz RJ, Morisaki T. T-box 2, a mediator of Bmp-Smad signaling, induced hyaluronan synthase 2 and Tgfbeta2 expression and endocardial cushion formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18604–18609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900635106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang W, et al. Tbx20 transcription factor is a downstream mediator for bone morphogenetic protein-10 in regulating cardiac ventricular wall development and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:36820–36829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Boer BA, van den Berg G, de Boer PA, Moorman AF, Ruijter JM. Growth of the developing mouse heart: an interactive qualitative and quantitative 3D atlas. Dev. Biol. 2012;368:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakraborty S, Sengupta A, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and persistence of fetal characteristics in adult mouse hearts. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chakraborty S, Yutzey KE. Tbx20 regulation of cardiac cell proliferation and lineage specialization during embryonic and fetal development in vivo. Dev. Biol. 2012;363:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu CC, et al. Spatially resolved genome-wide transcriptional profiling identifies BMP signaling as essential regulator of zebrafish cardiomyocyte regeneration. Dev. Cell. 2016;36:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiang FL, Guo M, Yutzey KE. Overexpression of Tbx20 in adult cardiomyocytes promotes proliferation and improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2016;133:1081–1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuji K, et al. BMP2 activity, although dispensable for bone formation, is required for the initiation of fracture healing. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1424–1429. doi: 10.1038/ng1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Del Monte G, et al. Differential notch signaling in the epicardium is required for cardiac inflow development and coronary vessel morphogenesis. Circ. Res. 2011;108:824–836. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.229062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.