Abstract

Objective

The objective of this article is to obtain detailed quantitative assessment of cerebellar function and structure in unselected migraine patients and controls from the general population.

Methods

A total of 282 clinically well-defined participants (migraine with aura n =111; migraine without aura n =89; non-migraine controls n =82; age range 43–72; 72% female) from a population-based study were subjected to a range of sensitive and validated cerebellar tests that cover functions of all main parts of the cerebellar cortex, including cerebrocerebellum, spinocerebellum, and vestibulocerebellum. In addition, all participants underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain to screen for cerebellar lesions. As a positive control, the same cerebellar tests were conducted in 13 patients with familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1; age range 19–64; 69% female) all carrying a CACNA1A mutation known to affect cerebellar function.

Results

MRI revealed cerebellar ischemic lesions in 17/196 (8.5%) migraine patients and 3/79 (4%) controls, which were always located in the posterior lobe except for one control. With regard to the cerebellar tests, there were no differences between migraine patients with aura, migraine patients without aura, and controls for the: (i) Purdue-pegboard test for fine motor skills (assembly scores p =0.1); (ii) block-design test for visuospatial ability (mean scaled scores p =0.2); (iii) prism-adaptation task for limb learning (shift scores p =0.8); (iv) eyeblink-conditioning task for learning-dependent timing (peak-time p =0.1); and (v) body-sway test for balance capabilities (pitch velocity score under two-legs stance condition p =0.5). Among migraine patients, those with cerebellar ischaemic lesions performed worse than those without lesions on the assembly scores of the pegboard task (p <0.005), but not on the primary outcome measures of the other tasks. Compared with controls and non-hemiplegic migraine patients, FHM1 patients showed substantially more deficits on all primary outcomes, including Purdue-peg assembly (p <0.05), block-design scaled score (p <0.001), shift in prism-adaptation (p <0.001), peak-time of conditioned eyeblink responses (p <0.05) and pitch-velocity score during stance-sway test (p <0.001).

Conclusions

Unselected migraine patients from the general population show normal cerebellar functions despite having increased prevalence of ischaemic lesions in the cerebellar posterior lobe. Except for an impaired pegboard test revealing deficits in fine motor skills, these lesions appear to have little functional impact. In contrast, all cerebellar functions were significantly impaired in participants with FHM1.

Keywords: Migraine, hemiplegic migraine, cerebellum, infarcts, magnetic resonance imaging

Background

A range of clinical neurophysiological and functional imaging studies have suggested that migraine might be associated with cerebellar dysfunction (1–10). However, these studies were all conducted in patients who were selected from headache clinics and thus likely are on the more severe end of the clinical spectrum. Moreover, tests were not analysed blinded for diagnosis, and most migraine patients were using antimigraine medications potentially interfering with cerebellar function. Therefore, it is still uncertain whether migraine is associated with cerebellar dysfunction, and, if so, to what extent and why? Is cerebellar dysfunction due to the increased prevalence of cerebellar ischaemic lesions in migraine patients or is there a more functional explanation similar to what’s seen in familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 (FHM1) (11,12)? Although a systematic quantitative assessment of cerebellar function in FHM has never been conducted, many FHM1 patients have signs of cerebellar ataxia on clinical examination (13). In the present study we systematically and quantitatively assessed in detail (i) motor and non-motor cerebellar function, (ii) presence and distribution of ischaemic lesions in the cerebellum and other parts of the brain, and (iii) the relationship between cerebellar lesions and dysfunction in 200 unselected patients with migraine with or without aura from the general population. The results were analysed blinded for diagnosis and compared with those obtained in 82 non-migraine control individuals and, as a positive control, 13 patients with genetically proven FHM1.

Methods

Participants

Individuals with migraine with aura (n =111, MA) or without aura (n =89, MO) and non-migraine controls (n =82) were all participants from the population-based Cerebral Abnormalities in Migraine, an Epidemiological Risk Analysis Cohort (CAMERA II) study, which was primarily aimed at assessing longitudinal progression of brain lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (14). All participants were invited to undergo cerebellar functions tests on the day MRI was performed. Participants were allowed to complete some or all tests, according to available time on the test occasion. No specific selection criteria were used. The study individuals were not informed about the specific goals of each test to avoid selection bias. Fifteen patients with genetically proven FHM1 were invited as positive controls, 13 of whom (mean age 42 years, range 19–64; 69% female) agreed to participate.

All individuals with migraine were investigated in between attacks (at least two days after a previous and before a next attack). Thus, participants who developed an attack within 48 hours following data collection were retested later. All participants were interviewed on the use of medication, alcohol, or sedatives in the 24 hours prior to examination. Informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The Human Research and Review committee at the Leiden University Medical Center approved study procedures.

Neurological examination

All clinical examinations, tests, and data-processing were conducted by HK and IPM, who remained blinded for the individual diagnoses and clinical characteristics of the participants throughout the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and physical examination.

| Controls (n =82) | MA (n =111) | MO (n =89) | FHM1 (n =13) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 55 (7.5) | 57 (8.1) | 58 (7.5) | 42 (13.3) |

| Female gender | 72% | 72% | 71% | 67% |

| Right-handedness | 91% | 93% | 94% | 100% |

| Mean attacks per year (SD; range) | Na | 14 (20; 1–170) | 19 (19; 2–105) | 7 (14; 1–52) |

| Cerebellar lesion on MRI | 4% | 10% | 7% | 0% |

| Medication: | ||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 5% | 1% | 23% |

| Triptans | NA | 14% | 8% | 8% |

| Sedatives | 5% | 8% | 10% | 8% |

| Physical examination | ||||

| Limb hypermetria/ataxia | 4% | 2% | 3% | 15% |

| Dysdiadochokinesis | 3% | 4% | 2% | 8% |

| Hypermetric eye movements | 3% | 2% | 1% | 0% |

Physical examination is available in 282 +12. MRI is available in 275 +2 participants.

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging;

NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

MRI

Whole-brain MR images were acquired using a 1.0T system in Doetinchem (Magnetom Harmony; Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) and 1.5T scanner in Maastricht (ACS-NT; Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). For additional information see online supplemental information.

Cerebellar tests

The cerebellar tests we used assess functions mediated by cerebrocerebellum, spinocerebellum, and vestibulocerebellum. The Purdue pegboard test is a specific test of fine motor skills (15), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition (WAIS-III) block-design test assesses visuospatial ability to rotate objects mentally (16), the prism adaptation task tests subconscious arm movement learning (17), the eyeblink conditioning task tests acquisition of conditioned responses and learning-dependent timing of these responses (18,19) and the body-sway test evaluates balance capabilities (20–22). For additional information on all separate cerebellar tests, see online supplemental methods and e-Figure 1.

Statistical analyses

Participants with MA, MO, controls and FHM1 patients were averaged as separate groups and analysed in a comparative fashion off-line. Characteristics and neurological examination dichotomous variables were analysed with Chi square, and continuous variables with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For the pegboard, block-design, prism adaptation test and body-sway task, one-way ANOVA was used. For comparison of latencies to peak-time in the valid trials between groups during eyeblink conditioning, we used the Kruskal-Wallis analysis, as data were not normally distributed (with post-hoc analysis between two groups). For conditioned response (CR) onset, CR peak-amplitudes, and percentage of CRs in the valid trials between groups, we used a one-way ANOVA. For the body-sway test roll angle and angular velocity as well as pitch angle and angular velocity were analysed using the 90% range automatically produced by Swaystar software. For Swaystar analysis linear regression was used to adjust for age and body mass index (BMI). For analysis of cerebellar tests vs ischaemic lesions, groups (with and without ischaemic lesions) were compared using Chi square or one-way ANOVA. Analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 with significance levels set at 0.05. In addition, we used conservative p value for multiple comparisons applying Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons set at p ≤ 0.01.

Results

Neurological examination and MRI

Migraine and control individuals did not differ on baseline characteristics and physical neurological examination. Participants with FHM1 were on average younger and more frequently left-handed, and more frequently showed limb hypermetria and other signs of ataxia (Table 1).

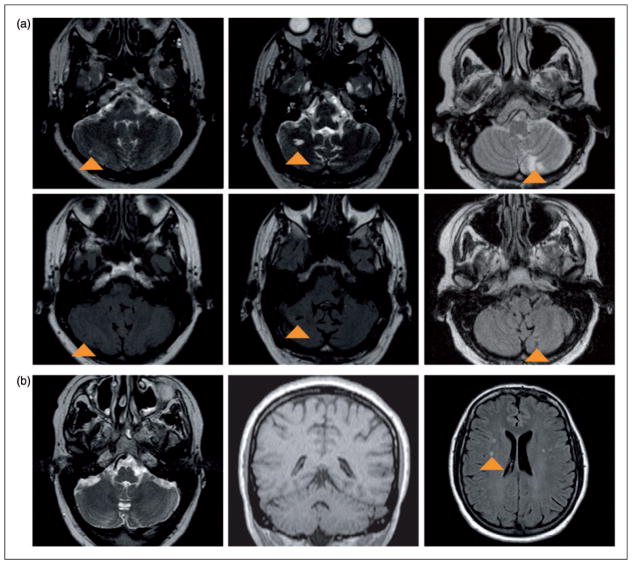

In total 20 participants had cerebellar ischaemic lesions: 11/110 (10%) of those with MA, 6/86 (7%) of those with MO, and 3/79 (4%) of the controls (Supplemental table). Examples of different sizes of cerebellar silent infarcts in migraineur subjects are shown in Figure 1. Recent MRI was available in only three participants with FHM1 and no cerebellar infarcts were present. Except in one control, these lesions were always located in the posterior lobe in the cerebellar hemispheres and paravermal region; no lesions were observed in the vermis or vestibulocerebellum (Supplemental table). Participants with cerebellar ischaemic lesions more frequently were left-handed compared to those without such lesions (5/20 (25%) vs 15/251 (6%); p =0.01; handedness unknown in four participants), but otherwise comparable for age, educational level and neurological examination.

Figure 1.

(a) Three examples of cerebellar infarcts in patients with migraine with aura. In the upper row T2-weighted images (infarcts appear as hyperintense parenchymal defects, indicated with arrowheads) and in the lower row corresponding FLAIR images. From left to right: female, 66 years old, with a small infarct in the right cerebellar hemisphere; male, 62 years old, with a medium-sized infarct in the right cerebellar hemisphere; and male, 54 years old, with multiple large infarcts in the left paravermal region. (b) MRI images from a 40-year-old male FHM1 patient, without cerebellar infarct or evidence of cerebellar or vermian atrophy; in the supratentorial white matter some nonspecific white-matter hyperintense lesions (arrowhead) are present (left image: transverse T2-weighted image; middle image: coronal T1-weighted image; right image: transverse FLAIR image). FLAIR: fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1.

Cerebellar tests

Purdue pegboard task

A total of 282 participants (111 MA, 89 MO, and 82 controls) underwent Purdue pegboard investigation. There were no differences between the three groups on the assembly task or any of the other outcome measures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics and outcomes of Purdue pegboard investigation.

| Controls (n =82) | MA (n =111) | MO (n =89) | p value three groups | FHM1 (n =12) | p value four groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 55 (7.5) | 57 (8.1) | 58 (7.5) | 42 (13.3) | ||

| Female gender | 72% | 72% | 71% | 67% | ||

| Right handedness | 91% | 93% | 100% | 100% | ||

| Mean attacks per year (SD; range) | NA | 14 (20; 1–170) | 19 (19; 2–105) | 7 (14; 1–52) | ||

| Cerebellar lesion MRI | 4% | 10% | 7% | NA | ||

| Medication: | ||||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 5% | 1% | 25% | ||

| Triptans | NA | 14% | 8% | 0% | ||

| Sedatives | 5% | 8% | 10% | 8% | ||

| Outcomes Purdue pegboard | ||||||

| Assembly task | 7.3 (1.9) | 6.8 (1.9) | 7.3 (1.9) | 0.1 | 6.0 (1.3) | 0.04a |

| Right-handed task | 13.7 (2.3) | 13.6 (2.1) | 13.1 (2.3) | 0.1 | 12.0 (2.0) | 0.03a |

| Left-handed task | 13.2 (2.2) | 13.3(2.2) | 13.1 (2.4) | 0.9 | 12.8 (2.3) | 0.9 |

| Both-handed task | 10.5 (1.8) | 10.8 (2.0) | 10.8 (1.9) | 0.6 | 10.5 (2.4) | 0.8 |

| Sum score | 37.5 (5.4) | 37.5 (5.5) | 37.0 (5.7) | 0.8 | 35.0 (4.9) | 0.5 |

Tabled values represent the group means and standard deviations (SD), except for the variable gender, right handedness, medication and cerebellar lesions. Handedness data were taken from 278 +12 participants; MRI participants with pegboard from 275. Pegboard tasks are displayed as mean pegs during 30 seconds (SD). Range right-handed task covers 5–19 pegs, range sum score covers 16–50 pegs, and range assembly task 2–12 pegs.

Bonferroni post-hoc analysis all <0.05 for FHM1 vs controls, FHM1 vs MA and FHM1 vs MO.

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

The 20 individuals with a cerebellar ischaemic lesion performed significantly worse on most pegboard tasks (assembly task 5.9 vs 7.3, p =0.002; number of pegs with right hand 12.4 vs 13.6 in non-infarct group, p =0.03; and number of pegs with both hands 9.4 vs 10.8, p =0.001) (Supplemental table). Among migraine patients the 17 with cerebellar ischaemic lesions on average performed worse than the 183 migraine patients without such lesions (assembly task 5.9 vs 7.3, respectively, p =0.005; number of pegs with right hand 11.8 vs 13.5, p =0.003; and number of pegs with both hands 9.5 vs 10.9, p =0.006) (Supplemental table and Table 2). Participants with FHM1 (n =12) performed significantly worse on the assembly score (p =0.04) and right-handed tasks (p =0.03), but not on the other pegboard scores (Table 2).

Block-design test

A total of 202/282 (72%) participants (82 MA, 62 MO, and 58 controls) underwent the block-design test. The scaled score (primary endpoint) as well as the raw score and percentage within the highest tertile of scaled score (secondary endpoints) were not significantly different between migraine patients with or without aura and controls (Table 3). Participants with cerebellar ischaemic lesions (n =9) did not perform worse than those without (Supplemental table and Table 3). Participants with FMH1 (n =12) obtained significantly lower scores on the block-design test than the other three study groups. None of the participants with FHM1 was in the highest tertile of scaled scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant characteristics and outcomes of block design test.

| Controls (n =58) | MA (n =82) | MO (n =62) | p value three groups | FHM1 (n =12) | p value four groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 55 (7.3) | 57 (8.2) | 58 (7.4) | 42 (13.3) | ||

| Female gender | 64% | 70% | 76% | 67% | ||

| Right-handedness (%) | 91% | 95% | 94% | 100% | ||

| Mean attacks per year (SD; range) | NA | 17 (26; 1–170) | 17 (17; 2–105) | 7 (14; 1–52) | ||

| Cerebellar lesion MRI | 2% | 8% | 3% | NA | ||

| Medication: | ||||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 0% | 0% | 25% | ||

| Triptans | NA | 11% | 8% | 0% | ||

| Sedatives | 2% | 10% | 8% | 8% | ||

| Outcomes block design test | ||||||

| Mean scaled score (SD) | 9.8 (3.2) | 10.7 (3.6) | 9.7 (3.3) | 0.2 | 4.0 (3.0) | < 0.001a |

| Scaled score, high | 11 (19%) | 27 (33%) | 15 (24%) | 0.2 | 0 (0%) | 0.047 |

| Mean raw score (SD) | 30.3 (14.6) | 33.5 (15.9) | 29.5 (13.9) | 0.2 | 13.4 (11.3) | < 0.001a |

Handedness known for 198 +12 participants. Neurological examination for 200 +12 participants. MRI for 199 participants. High education defined as university of professional education or higher; block-design test scaled score was recoded in tertiles (low, medium, high), low 4–7, medium 8–12, high 13–19; analysis of variance (ANOVA) post hoc

Bonferroni all <0.001.

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

Prism adaptation test

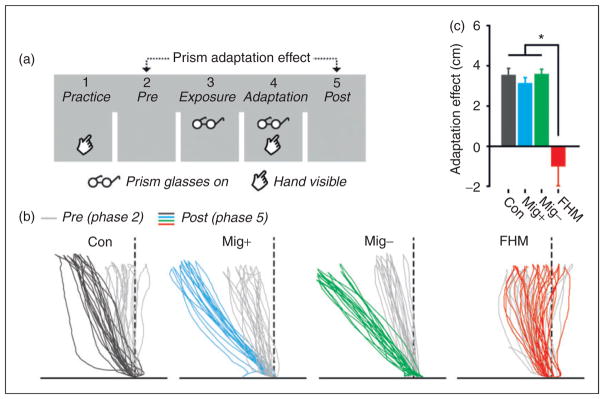

A total of 132/282 (47%) individuals (49 MA, 44 MO, and 39 controls) participated in the prism goggles adaptation test (Table 4). Accurate goal-directed hand movements towards the target were similar in all three study groups. No significant differences between groups in prism-induced hand movement adaptation (primary endpoint; phase five vs phase two) or movement variability (Figure 2; Table 4) were found. Of 128 participants in the prism adaptation test who also underwent MRI, seven had cerebellar ischaemic lesions, five of whom had MA. No differences were found between these small sub-groups (Supplemental Table and Table 4).

Table 4.

Participant characteristics and outcomes of prism adaptation test.

| Controls (n =39) | MA (n =49) | MO (n =44) | p value three groups | FHM1 (n =12) | p value four groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 55 (7) | 58 (8) | 57 (7) | 42 (13) | ||

| Female gender | 62% | 78% | 77% | 75% | ||

| Right-handedness | 87% | 94% | 96% | 100% | ||

| Mean attacks per year (SD; range) | NA | 14 (15; 1–105) | 18 (20; 2–105) | 7 (14; 1–52) | ||

| Cerebellar lesion MRI | 3% | 11% | 2% | NA | ||

| Medication: | ||||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 2% | 0% | 25% | ||

| Triptans | NA | 15% | 9% | 0% | ||

| Sedatives | 2% | 10% | 8% | 8% | ||

| Outcomes prism adaptation | ||||||

| Adaptation in cm (SD) | 3.5 (1.8) | 3.1 (1.6) | 3.6 (1.7) | 0.8 | −1.0 (3.4) | < 0.001a |

| Mean horizontal shift task 4 in cm (SD) | 0.9 (3.1) | 1.2 (2.7) | 1.2 (2.6) | 0.8 | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.5 |

| Mean horizontal shift task 5 in cm (SD) | −4.3 (2.5) | −3.7 (1.8) | −3.9 (2.2) | 0.8 | −0.3 (2.1) | < 0.001a |

Mean horizontal shift task 4; horizontal shift with prism goggles and with feedback. Mean horizontal shift task 5; horizontal shift after prism goggles being removed, negative values indicate leftward shift. Adaptation; defined as mean x-coordinate task 5 minus mean x-coordinated task 2.

Bonferroni post-hoc analysis all <0.001 for FHM1 vs controls, FHM1 vs migraine with aura and FHM1 vs migraine without aura.

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Prism adaptation task in non-migraine controls, migraine patients with or without aura, and patients with FHM1. (a) The prism adaption experiment consisted of five phases in which participants had to move their hand to a visible target with or without visible feedback of their hand and with or without wearing prism glasses. In the adaptation phase (phase 4) participants learned to align their hand movements to the target that was visually shifted due to the prism glasses. (b) Individual raw hand movements in phase 2 (pre-adaptation) and phase 5 (post-adaptation) of four participants show that wearing prism glasses induces changes in hand movements, except for the FHM1 patient. (c) Overall, the prism adaptation effect was present in the control group and both groups of migraine patients, whereas the FHM1 group showed no prism adaptation effect. FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1.

In the 12 participants with FHM1 the prism-induced hand movement adaptation was greatly reduced compared to the other groups, both with regard to the general adaption (phase five vs phase two) and mean horizontal shift of task five (in both cases, four group comparison p <0.001; Figure 2).

Eyeblink conditioning

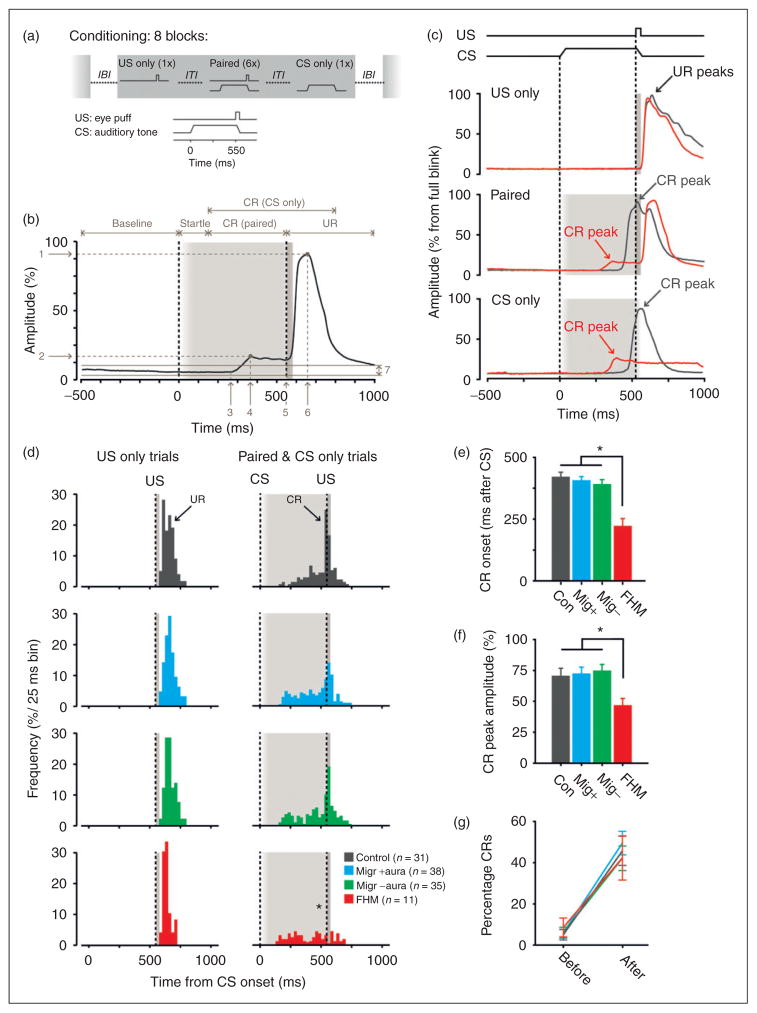

We performed eyeblink conditioning in 104/282 (37%) participants (38 MA, 35 MO, and 31 controls). Latency to onset, latency to peak-time, peak-amplitude, and percentage of conditioned responses did not differ between the three study groups (Figure 3 (d)–(g); Table 5). Adjusting for gender and age did not alter these findings. Cerebellar ischaemic lesions were found in 6/103 of the participants who also underwent MRI; three with MA, two with MO, and one control. Four of these lesions were located in the posterior paravermis and two in the posterior hemisphere, but none in the critical eyeblink region HVI (10,23) (see also supplemental table). No differences in latency to peak-time (p =0.5) or peak-amplitude (p =0.1) of the conditioned responses were found between participants with and without cerebellar ischaemic lesions. In participants with FHM1 (n =11) mean latency to onset and peak-time of conditioned responses deviated significantly (p =0.001 and p =0.01, respectively) from the other study groups; both time points occurred earlier, preventing optimal closure of the eyelid when the unconditioned stimulus was about to occur (Figure 3(c)–(e)). In addition, the mean peak-amplitude of participants with FHM1 was significantly smaller (p =0.045) than the amplitudes in the other three study groups (Figure 3(c), (f)). When looking at percentage of CRs before (block 1) and after training (maximum percentage in block 6, 7 or 8), all three study groups showed a similar significant increase (before training between groups p =0.9, one-way ANOVA; after training between groups p =0.8, one-way ANOVA; before training vs after training p all groups <0.001, paired t-test) (Figure 3(g)). Together these data show no difference in conditioning between controls and participants with migraine. On the other hand, participants with FHM1 learn to make the association between conditioned and unconditioned stimulus (similar CR percentages), but are unable to produce a strong, properly timed eyeblink (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Eyeblink conditioning in non-migraine controls, migraine patients with or without aura, and patients with FHM1. (a) Experimental paradigm for the eyeblink conditioning task. The unconditioned stimulus (US) was a mild air puff (30 ms), which was applied to the left eye and elicited a reflexive eyeblink. The conditioned stimulus (CS) was a clearly audible tone (1 kHz, 70–80 dB, duration 580 ms), presented via headphones. Each training session consisted of eight blocks, separated by an inter-block interval (IBI) of 120 ± 20 s. Each block in turn consisted of eight trials separated by an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 30 ± 10 s. CS and US were presented in a delay paradigm, in which the interval between CS- and US-onset was 550 ms. (b) Analysis of raw data traces. Eyelid movements larger than the 2 ± SD of the 500 ms pre-CS period were considered as significant and further categorised into auditory startle response (latency to peak 10–150 ms) and cerebellar conditioned responses (CRs; latency to peak 150–600 ms). The peak-amplitude for all responses was expressed as the percentage of the averaged peak-amplitude in all US-only trials for that participant. Arrows indicate: 1 unconditioned response (UR) peak-amplitude, 2 CR peak-amplitude, 3 CR onset, 4 CR peak-time, 5 UR onset, 6 UR peak-time, and 7 2 ± SD of 500 ms pre-CS baseline period. (c) Examples of raw data traces obtained from a control (anthracite line) and FMH1 patient (red line). In US-only trials (upper panel) controls and FMH patients show a normal reflexive eyelid closure. In paired (middle panel) and CS-only trials (lower panel) controls show large amplitude and perfectly timed CRs, i.e. the peak of the CR is exactly at the point where the US is delivered. FHM1 patients show CRs, but those CRs have much smaller amplitudes. In addition, the timing of their CRs is severely impaired in that they start too early and therefore reach the maximum eyelid closure too early. (d) Right panels. Peak timing of CRs over all eight training blocks per group. Controls, and migraine patients with and without aura show a clear preference in the peak-time of their CR around the US onset. FHM1 patients completely lack this timing aspect in their CRs (asterisk). Left panels. For comparison we plotted the peak timing of URs over all eight training blocks in US-only trials, in which no difference was found between the four groups. (E) CR onset over all eight training blocks per group. FHM1 patients have CRs that started significantly earlier than CRs in controls, migraine patients with and without aura. (f) CR peak-amplitude over all eight training blocks per group. FHM1 patients have significantly smaller CR amplitudes than controls and migraine patients with and without aura. (g) No difference was found between groups in the CR percentage before training (block 1) and after training (maximum percentage in either block 6, 7 or 8). FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1.

Table 5.

Participant characteristics and outcomes of eyeblink conditioning test.

| Controls (n =31) | MA (n =38) | MO (n =35) | p value three groups | FHM1 (n =11) | p value four groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 54 (7.0) | 57 (8.4) | 56 (6.8) | 40 (12.9) | ||

| Female gender | 58% | 58% | 77% | 73% | ||

| Right-handedness | 93% | 92% | 91% | 100% | ||

| Mean attacks per year (SD; range) | NA | 14 (26; 1–170) | 16 (19; 3–105) | 7 (15; 1–52) | ||

| Cerebellar lesion MRI | 3% | 8% | 6% | NA | ||

| Medication: | ||||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 3% | 0% | 27% | ||

| Triptans | NA | 13% | 8% | 9% | ||

| Sedatives | 0% | 10% | 7% | 9% | ||

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Latency to CR peak time (ms) | 554 (85.6) | 520 (89.8) | 501 (100.3) | 0.3 | 420 (92.5) | 0.01a |

| Latency to CR onset (ms) | 421 (90.6) | 405 (84.9) | 387 (87.1) | 0.4 | 224 (94.7) | <0.001b |

| Peak amplitude CR (% from full UR) | 72.3 (30.3) | 72.9 (30.7) | 74.2 (26.9) | 0.98 | 46.2 (16.9) | 0.045c |

| Percentage CR before training | 5 (13) | 6 (15) | 6 (14) | 0.9 | 9 (14) | 0.9 |

| Percentage CR after training | 46 (36) | 50 (33) | 42 (33) | 0.7 | 42 (34) | 0.8 |

MRI n =103; all eyeblink conditioning values are expressed as mean ± SD.

p value for four-group comparison Kruskal-Wallis test; post hoc; MA vs FHM1 p =0.01, MO vs FHM1 p =0.03, Control vs. FHM1 p =0.001.

p value four-group comparison one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), post hoc all comparison <0.001.

p value for four-group comparison ANOVA); post hoc; MA vs FHM1 p =0.02, MO vs FHM1 p =0.005, Control vs. FHM1 p =0.014. All peak-time and onset values of conditioned responses (CRs) expressed as latency in milliseconds after onset of conditioned stimulus (CS); CR amplitude expressed as percentage from full eyelid closure. When looking at CR percentage before (block 1) and after training (maximum percentage in block 6, 7 or 8), all groups showed a significant increase (p all groups <0.001).

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

Body-sway task

In total 177/282 (63%) participants (71 MA, 53 MO, and 53 controls) completed the body-sway task. Most subjects completed the two-legged stance condition 155/177 (88%), compared to 136 participants (77%) for walking condition and 77 participants (44%) who completed the one-legged stance step condition. The proportions of participants who could complete the separate conditions did not differ among the three study groups; neither did the other body-sway parameters such as roll angle, roll velocity, pitch angle, and pitch velocity (Table 6). This remained so after adjusting for age and BMI.

Table 6.

Participant characteristics and outcomes of body sway test.

| Controls (n =53) | MA (n =71) | MO (n =53) | p value three groups | p value model 1 | FHM1 (n =13) | p value four groups | p value model 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||||||||

| Mean age (SD) | 55 (7.3) | 58 (8.1) | 58 (7.3) | 42 (13) | ||||

| Female gender | 62% | 72% | 72% | 69% | ||||

| Body mass index (SD) | 26 (3.6) | 26 (3.9) | 25 (3.4) | 25 (3.8) | ||||

| Alcohol use last 12 hours | 10% | 1% | 4% | 0% | ||||

| Mean attacks per year ((SD; range) | NA | 17 (27; 1–170) | 17 (17; 2–105) | 7 (14; 1–52) | ||||

| Cerebellar lesion MRI | 2% | 7% | 4% | NA | ||||

| Medication: | ||||||||

| Migraine prophylaxis | NA | 0% | 0% | 23% | ||||

| Triptans | NA | 10% | 8% | 8% | ||||

| Sedatives | 2% | 10% | 8% | 8% | ||||

| Outcomes | ||||||||

| Two-legs stance condition | ||||||||

| Completed | n =44 (83%) | n =63 (89%) | n =48 (91%) | 0.5 | NA | n =12 (92%) | 0.6 | NA |

| Roll angle | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.4) | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.0 (0.7) | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Roll velocity | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.6) | 0.8 | 0.5 | 2.1 (1.4) | 0.02 | 0.1 |

| Pitch angle | 1.4 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.7 | 0.6 | 2.2 (0.8) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Pitch velocity | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.5) | 2.1 (0.7) | 0.5 | 0.2 | 4.2 (2.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| One-leg stance step condition | ||||||||

| Completed | n =20 (38%) | n =33 (47%) | n =24 (45%) | 0.6 | NA | n =0 (0%) | 0.01 | Na |

| Roll angle | 8.0 (2.2) | 7.6 (2.2) | 8.2 (2.7) | 0.6 | 0.6 | NA | NA | NA |

| Roll velocity | 22.7 (6.0) | 20.2 (5.5) | 22.6 (7.3) | 0.3 | 0.1 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pitch angle | 6.1 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.4) | 6.3 (2.3) | 0.8 | 0.4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Pitch velocity | 39.3 (10.9) | 34.0 (8.1) | 34.5(9.5) | 0.2 | 0.03 | NA | NA | NA |

| Walking condition | ||||||||

| Completed | n =39 (78%) | n =58 (83%) | n =39 (75%) | 0.6 | NA | n =12 (92%) | 0.5 | NA |

| Roll angle | 8.5 (3.3) | 7.9 (3.6) | 7.4 (3.02) | 0.4 | 0.2 | 6.8 (3.3) | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Roll velocity | 28.7 (6.7) | 26.4 (7.2) | 27.4 (8.2) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 31.7 (7.9) | 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Pitch angle | 8.1 (3.2) | 8.0 (3.1) | 6.9 (2.4) | 0.1 | 0.3 | 7.1 (1.6) | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Pitch velocity | 31.9 (9.4) | 30.2 (8.6) | 28.2 (8.8) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 40.6 (7.7) | <0.001 | 0.02 |

Data represent mean (SD), or numbers (percentage in parenthesis). MRI is available in 174 participants. Medication use indicates current users. Completed: participant performed on all separate tasks of the condition for at least five seconds. Number of participants differs between two-leg stance, one-leg stance stepping condition and walking condition, as participants had to complete all separate tasks of a particular condition. Number of individuals participating in walking task was 185, as five patients refused. P value Model 1 =p value using linear regression with adjustment for BMI and age. Post-hoc comparisons are given in text.

MA: migraine with aura; MO: migraine without aura; FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; BMI: body mass index; NA: not applicable; SD: standard deviation.

Brain imaging was available for 174/177 (98%) participants, eight of whom (seven with migraine) had a cerebellar ischaemic lesion. These performed equally well on all sub-tasks of the body-sway test as the participants without such a lesion (data not shown).

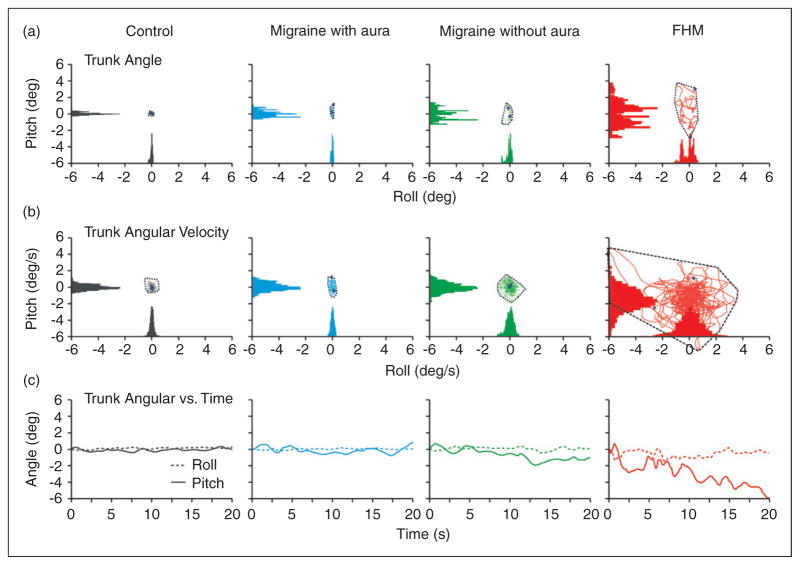

When including participants with FHM1 in a four-group comparison with controls and participants with migraine with or without aura, pitch angle velocity (F (3,164) =24.1, p <0.001) and pitch angle (F (3,164) =13.3, p <0.001) were significantly different. Post hoc analysis using the Bonferroni-test showed that for the two-legged stance condition the mean pitch angle velocity (4.2; SD 2.2) and pitch angle (2.2; SD 0.8) for participants with FHM1 were significantly higher than those in controls and participants with migraine with or without aura (Figure 4). These differences remained so after adjustments for BMI and age (see Model 1 in Table 6). None of the participants with FHM1 could complete the one-legged stance step condition. When evaluating all six individual tasks of this test separately, sway measurements were significantly increased in both pitch and roll directions in participants with FHM1 compared to the other groups (Table 6). During the walking condition post hoc comparisons using the Bonferroni-test indicated that the mean pitch velocity for participants with FHM1 (40.6 degrees per sec, SD 7.7) was significantly higher compared to controls (31.9 degrees per sec, SD 9.4) and participants with migraine (30.2 degrees per sec, SD 8.6) or without aura (28.2 degrees per sec, SD 8.8). These differences remained significant after adjusting for age and BMI.

Figure 4.

Body-sway measurements during one task of two-legged stance condition (two legs with eyes closed on foam) for individual participants. Panels show pitch angle vs roll angle (top row), pitch angle velocity vs roll angle velocity (middle row), and angles for roll and pitch over time (bottom row) for a healthy control, migraineur with aura, migraineur without aura and FHM1 patient, from left to right, respectively. Note that for all parameters controls and migraine patients are similar, whereas the FHM1 patient stands out showing deviations and instability. FHM1: familial hemiplegic migraine type 1.

Discussion

We tested the hypotheses (i) that migraine is associated with cerebellar dysfunction and (ii) that this might be due to increased prevalence of cerebellar ischaemic lesions. To this end we systematically assessed motor and non-motor cerebellar function of unselected but well-defined migraine patients with or without aura from the general population by using an array of sensitive and validated tests covering all main functions of the cerebellar cortex. In addition, all participants underwent brain MRI to screen for cerebellar lesions. Results were compared with those obtained in non-migraine controls and, as a positive control, participants with genetically proven FHM1. Whereas participants with FHM1 performed worse compared both to controls and participants with non-hemiplegic migraine on the primary outcomes of all behavioural tests, participants with non-hemiplegic migraine did not differ from non-migraine controls for: (i) fine motor speed and coordination as evaluated with the Purdue pegboard task; (ii) perceptual intelligence and motor function as evaluated with the WAIS-III block-design test; (iii) cerebellar motor coordination and learning of limb movements as evaluated with the prism adaptation test; (iv) associative cerebellar motor learning evaluated with the eyeblink conditioning paradigm; and (v) vestibular motor coordination and adaptation as evaluated with the body-sway test. Participants with migraine who had cerebellar ischaemic lesions performed worse on some parameters of the pegboard task, but not on the other cerebellar motor tasks.

Cerebellar function in migraine patients from the general population

The present study is the first to assess cerebellar function in detail over a wide range of modalities in a large and unselected but clinically well-characterised group of migraine patients from the general population. Whereas previous studies suggested subclinical cerebellar dysfunction in migraine patients who were drawn from headache clinics (1,6,10), we failed to find any evidence of impaired cerebellar function in the ‘average migraine patient’ from the general population despite using a diverse set of highly sensitive clinical tests.

We employed a wide array of tests, which together cover functions of all main parts of the cerebellar cortex including cerebrocerebellum (hemispheres; e.g. Purdue pegboard task, block-design test and eyeblink conditioning), spinocerebellum (vermis and paravermis; e.g. prism adaptation test and eyeblink conditioning) and vestibulocerebellum (flocculus and nodulus; e.g. body-sway test) (23–30). The cerebrocerebellum receives input from the cerebral cortex and mainly controls planning of movements, while the spinocerebellum and vestibulocerebellum receive inputs from spinal cord and brainstem regions involved in sensory pro-prioceptive, vestibular and visual processing and mainly control execution of limb, eye and head movements (31–33). Moreover, the tests probably also cover functions of both the anterior and posterior lobe (25,26,28–30). The posterior lobe may differ from the anterior lobe in that it may be more prominently involved in non-motor cognitive and autonomic functions (31,34–37), and/or visuomotor planning (32).

Our results diverge from those obtained in other studies (1,2,6,10). These studies were small and included migraine patients who were all selected from headache clinics. As a consequence, many of these patients most likely were on the more severe end of the clinical migraine spectrum and were using antimigraine medications potentially interfering with cerebellar functions. Moreover, the researchers in these studies were not blinded for diagnosis while using only single test paradigms such as the pointing paradigm or posturographic measures of sway (1,6), which are potentially open for bias. We don’t believe the contrasting findings were due to use of different tests. The pointing paradigm resembles the prism paradigm we used in that it also compares motor output of the forelimbs before and after manipulating visual feedback and the posturographic measures of sway were similar to our body-sway test (1,6). Conditioned eye-blink responses measured with the use of electromyography (EMG) (10), can be readily repeated with the more sensitive Magnetic Distance Measurement Technique (MDT) method used in the current study (19). Finally, as we did find significant differences in a relatively small group of FHM1 patients with the same set of tests, we are reassured that the tests we employed were sufficiently sensitive to detect differences. Thus, in contrast to previous findings (1,7,8,38), our findings argue against the hypothesis that cerebellar function is altered in the average migraine patient. Moreover the results of our study underline the importance of including unbiased study populations and ensuring that investigators are blinded for clinical diagnosis.

The effect of cerebellar ischaemic lesions on cerebellar function

A conspicuous advantage of our study was that virtually all migraine patients and controls (275/282; 98%) were subjected to detailed brain MRI as part of the CAMERA-2 study. In total 20/275 (7%) individuals, 17 with migraine and three controls, showed cerebellar ischaemic lesions, eight had an isolated cerebellar ischaemic lesion. Migraine patients with cerebellar ischaemic lesions performed significantly worse on multiple outcomes of the pegboard task including the assembly score, number of pegs with right hand and number of pegs with both hands. However, outcome parameters of all other cerebellar tests were not affected.

Why we detected deficits only with the pegboard test remains elusive. Possibly the cerebellar ischaemic lesions were accidently selectively localised in the cerebellar lobules involved in pegboard performance, but not the other tests. Such an explanation would be in line with the finding that the patients with impaired pegboard performance all showed larger lesions mainly in the posterior lobules (Supplemental table), which is the cerebellar region presumably responsible for this task (29,31,34). The anterior lobe can also contribute to limb movements (39). However, as indicated by several studies (29,31,34) the fine finger movements, as tested intensely by the pegboard test, rely mainly heavily on the loop between the posterior cerebellum and cerebral cortex. Alternatively, performance of the pegboard task might also depend on cerebral cortical function (29), and the individuals suffering from impaired pegboard performance might accidently show ischaemic lesions in both the cerebellum and supratentorial regions (possibly even including white-matter lesions). Such a hypothesis would be compatible with findings by Brighina and colleagues (7), who found in MA patients a significant deficit in cerebellar inhibition of cerebral cortical processing following conditioning with transcranial magnetic stimulation. However, several of the migraine patients with both cerebellar and supratentorial lesions had a good score on the pegboard task (supplemental table 2), whereas many with a bad score had no signs of cerebral cortical lesions. Studies at even higher MRI resolution and including even larger numbers of patients with possibly even more specific tests and multivariate lesion symptom mapping approaches might help to resolve this issue (40).

Cerebellar function in FHM1

In contrast to migraine patients, FHM1 patients showed impaired cerebellar function with significant differences for all primary and most secondary outcome measures of all five cerebellar function tests. As our group of FHM1 patients was small (n =13) and their average age was about 15 years younger (Table 1), the differences we found are likely to underestimate the true difference with non-hemiplegic migraine patients and controls. Our test findings were in line with the findings on physical examination and are in agreement with other studies on figural memory and executive function in FHM1 patients (41). Body-sway in FHM1 patients was particularly increased in the anterior-posterior direction, which is in line with findings in spinocerebellar ataxia patients (42). The symptoms of impaired motor and non-motor cerebellar function in FHM1 patients probably initially result directly from a different calcium influx in their Purkinje cells, the simple spike output of which is highly irregular early on (43,44). These electrophysiological aberrations have been shown to be sufficient to cause ataxia (43,45,46), but they will also induce changes in energy consumption and contribute to cerebellar degeneration over time (47,48). Thus, the combination of these pathophysiological mechanisms following the FHM1 CACNA1A mutation increasingly affects the capabilities for motor learning and consolidation, and ultimately leads to motor performance problems and overt signs of ataxia (45). However, as we did not have (recent) MRI imaging of most FHM1 patients, any effect of possible macroscopical structural lesions on cerebellar function can also not be ruled out.

Key findings

Migraine does not appear to be associated with cerebellar dysfunction, except perhaps in the most severely affected patients and in those with cerebellar ischaemic lesions that may affect some parameters of the pegboard task.

Patients with FHM1 show robust and general signs of cerebellar deficits, both at the level of motor and cognitive function, presumably reflecting disturbances in Purkinje cell calcium dynamics.

Supplementary Material

Clinical implications.

Cerebellar function is not impaired in migraineurs from the general population.

Silent cerebellar infarcts found in migraineurs can impair fine motor skills.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to E. Haasdijk, E. Goedknegt and M. Rutteman for technical assistance.

Author contributions include: Hille Koppen, Henk-Jan Boele and Inge H. Palm-Meinders collected and analysed the data and wrote the manuscript; Bastiaan J. Koutstaal, Corine G.C. Horlings, Bas K. Koekkoek, Jos van der Geest and Albertine E. Smit developed technical tools for the experiments and collected the data; Mark A. van Buchem, Lenore J. Launer, Gisela M. Terwindt, Bas R. Bloem and Mark C. Kruit provided the facilities and financial means for the experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; Michel D. Ferrari and Chris I. De Zeeuw designed the experiments, gathered financial means for the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from NWO-ALW, NWO-ZON-MW, Neuro-Basic, EU-ERC, and Prinses Beatrix Fonds (all CIDZ), NWO (903-52-291, MDF), VICI (VICI 918-56-602, MDF), Spinoza (2009, MDF), Dutch Heart Foundation (2007B016, MDF and MCK), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1R01NS061382-01, MDF and MCK), NWO (907-00-217, GMT) and VIDI (917-11-319, GT), Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH (LJL).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Sandor PS, Mascia A, Seidel L, et al. Subclinical cerebellar impairment in the common types of migraine: A three-dimensional analysis of reaching movements. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:668–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishizaki K, Mori N, Takeshima T, et al. Static stabilometry in patients with migraine and tension-type headache during a headache-free period. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:85–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harno H, Hirvonen T, Kaunisto MA, et al. Subclinical vestibulocerebellar dysfunction in migraine with and without aura. Neurology. 2003;61:1748–1752. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098882.82690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furman JM, Sparto PJ, Soso M, et al. Vestibular function in migraine-related dizziness: A pilot study. J Vestib Res. 2005;15:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dodick DW, Roarke MC. Crossed cerebellar diaschisis during migraine with prolonged aura: A possible mechanism for cerebellar infarctions. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:83–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akdal G, Donmez B, Ozturk V, et al. Is balance normal in migraineurs without history of vertigo? Headache. 2009;49:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brighina F, Palermo A, Panetta ML, et al. Reduced cerebellar inhibition in migraine with aura: A TMS study. Cerebellum. 2009;8:260–266. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassab M, Bakhtar O, Wack D, et al. Resting brain glucose uptake in headache-free migraineurs. Headache. 2009;49:90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teggi R, Colombo B, Bernasconi L, et al. Migrainous vertigo: Results of caloric testing and stabilometric findings. Headache. 2009;49:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerwig M, Rauschen L, Gaul C, et al. Subclinical cerebellar dysfunction in patients with migraine: Evidence from eyeblink conditioning. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:904–913. doi: 10.1177/0333102414523844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruit MC, van Buchem MA, Hofman PA, et al. Migraine as a risk factor for subclinical brain lesions. JAMA. 2004;291:427–434. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher AI, Gudmundsson LS, Sigurdsson S, et al. Migraine headache in middle age and late-life brain infarcts. JAMA. 2009;301:2563–2570. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ducros A, Denier C, Joutel A, et al. The clinical spectrum of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with mutations in a neuronal calcium channel. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:17–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palm-Meinders IH, Koppen H, Terwindt GM, et al. Structural brain changes in migraine. JAMA. 2012;308:1889–1897. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lorås H, Stensdotter AK, Öhberg F, et al. Individual differences in motor timing and its relation to cognitive and fine motor skills. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard JA, Seidler RD. Cerebellar contributions to visuomotor adaptation and motor sequence learning: An ALE meta-analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:27. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krab LC, de Goede-Bolder A, Aarsen FK, et al. Motor learning in children with neurofibromatosis type I. Cerebellum. 2011;10:14–21. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0217-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koekkoek SK, Hulscher HC, Dortland BR, et al. Cerebellar LTD and learning-dependent timing of conditioned eyelid responses. Science. 2003;301:1736–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1088383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koekkoek SK, Yamaguchi K, Milojkovic BA, et al. Deletion of FMR1 in Purkinje cells enhances parallel fiber LTD, enlarges spines, and attenuates cerebellar eyelid conditioning in Fragile X syndrome. Neuron. 2005;47:339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allum JH, Carpenter MG. A speedy solution for balance and gait analysis: Angular velocity measured at the centre of body mass. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:15–21. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horlings CG, Kung UM, Bloem BR, et al. Identifying deficits in balance control following vestibular or pro-prioceptive loss using posturographic analysis of stance tasks. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:2338–2346. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.07.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung UM, Horlings CG, Honegger F, et al. Postural instability in cerebellar ataxia: Correlations of knee, arm and trunk movements to center of mass velocity. Neuroscience. 2009;159:390–404. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Timmann D, Brandauer B, Hermsdorfer J, et al. Lesion-symptom mapping of the human cerebellum. Cerebellum. 2008;7:602–606. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener HC, Dichgans J, Bacher M, et al. Quantification of postural sway in normals and patients with cerebellar diseases. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1984;57:134–142. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(84)90172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeo CH, Hesslow G. Cerebellum and conditioned reflexes. Trends Cogn Sci. 1998;2:322–330. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mostofi A, Holtzman T, Grout AS, et al. Electrophysiological localization of eyeblink-related microzones in rabbit cerebellar cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8920–8934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6117-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye BS, Kim YD, Nam HS, et al. Clinical manifestations of cerebellar infarction according to specific lobular involvement. Cerebellum. 2010;9:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0200-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norris SA, Hathaway EN, Taylor JA, et al. Cerebellar inactivation impairs memory of learned prism gaze-reach calibrations. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:2248–2259. doi: 10.1152/jn.01009.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhn S, Romanowski A, Schilling C, et al. Manual dexterity correlating with right lobule VI volume in right-handed 14-year-olds. Neuroimage. 2012;59:1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thieme A, Thurling M, Galuba J, et al. Storage of a naturally acquired conditioned response is impaired in patients with cerebellar degeneration. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 7):2063–2076. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dietrichs E. Clinical manifestation of focal cerebellar disease as related to the organization of neural pathways. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2008;188:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickstein M, Sultan F, Voogd J. Functional localization in the cerebellum. Cortex. 2011;47:59–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voogd J, Schraa-Tam CK, van der Geest JN, et al. Visuomotor cerebellum in human and nonhuman primates. Cerebellum. 2012;11:392–410. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0204-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoodley CJ, Schmahmann JD. Functional topography in the human cerebellum: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2009;44:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA. Cerebellum and non-motor function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buckner RL, Krienen FM, Castellanos A, et al. The organization of the human cerebellum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:2322–2345. doi: 10.1152/jn.00339.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent M, Hadjikhani N. The cerebellum and migraine. Headache. 2007;47:820–833. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoogland TM, De Gruijl JR, Witter L, et al. Role of synchronous activation of cerebellar Purkinje cell ensembles in multi-joint movement control. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Kimberg DY, Coslett HB, et al. Support vector regression based multivariate lesion-symptom mapping. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014;2014:5599–5602. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2014.6944896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karner E, Delazer M, Benke T, et al. Cognitive functions, emotional behavior, and quality of life in familial hemiplegic migraine. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2010;23:106–111. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181c3a8a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Warrenburg BP, Bakker M, Kremer BP, et al. Trunk sway in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1006–1013. doi: 10.1002/mds.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoebeek FE, Stahl JS, van Alphen AM, et al. Increased noise level of Purkinje cell activities minimizes impact of their modulation during sensorimotor control. Neuron. 2005;45:953–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Z, Todorov B, Barrett CF, et al. Cerebellar ataxia by enhanced Ca(V)2. 1 currents is alleviated by Ca2+-dependent K+-channel activators in Cacna1a(S218L) mutant mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:15533–15546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2454-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Zeeuw CI, Hoebeek FE, Bosman LW, et al. Spatiotemporal firing patterns in the cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:327–344. doi: 10.1038/nrn3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Todorov B, Kros L, Shyti R, et al. Purkinje cell-specific ablation of Cav2. 1 channels is sufficient to cause cerebellar ataxia in mice. Cerebellum. 2012;11:246–258. doi: 10.1007/s12311-011-0302-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uncini A, Lodi R, Di Muzio A, et al. Abnormal brain and muscle energy metabolism shown by 31P-MRS in familial hemiplegic migraine. J Neurol Sci. 1995;129:214–222. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)00283-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elliott MA, Peroutka SJ, Welch S, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine, nystagmus, and cerebellar atrophy. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:100–106. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.