Abstract

Background:

Biochemical laboratory investigations help plan optimum management and communication in short- as well as long-term outcome to trauma victims.

Objective:

To assess the status of real-time values of biochemical laboratory investigations of different trauma patients and their association with overall mortality.

Materials and Methods:

Data based on prospective, observational registry of “Towards Improved Trauma Care Outcomes” (TITCO) from four Indian city hospitals. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, random blood sugar, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine of patients on admission were recorded. Logistic regression was applied with all biochemical investigation as independent variable and overall mortality as dependent variable.

Results:

Among 17047 trauma patients, 3456 with available laboratory result details were considered for this study. Overall mortality was 20% (range 14%–21%). For the higher laboratory results, value mortality was 21%–70%, with highest death (70%) for higher hemoglobin patients, followed by hematocrit (44%) and then creatinine (43%). Odds of high hemoglobin compared to normal were 15.20; odds of higher and lower of normal creatinine were 3.80 and 1.65 and for BUN were 2.17 and 1.92, respectively. Gender-wise significant difference was in overall female mortality (29%)% compared males (18%). Similar differences were replicated with results of each laboratory tests.

Conclusion:

The study ascertained the composite additional explanatory values of laboratory parameters in predicting outcome among injured patients in our population from Indian settings.

Keywords: Glucose, hemoglobin, laboratory parameters, outcome, trauma

INTRODUCTION

After severe trauma and hemorrhage, it is generally assumed that the rate of fluid shift from the interstitial space into the vasculature grossly modifies the biochemical laboratory investigations which may be critically followed for the prognosis of trauma victims. Prediction of outcome requires careful evaluation, analysis, and interpretation of demographic, clinical, imaging, and laboratory parameters which can help in planning the management and can help to communicate the short- as well as long-term outcome to the caretakers.[1] Studies have suggested that the investigations should be requested based on clinical and imaging findings and based on the suspicion which organs are involved.[2,3] Routine blood investigations are an important part of the evaluation who present with systemic injuries with variable role in predicting outcome. Although the natural history of posttraumatic acute kidney injury (AKI) is not well established, it is an uncommon but serious complication after trauma probably due to decreased renal perfusion as the common cause of this complication. Improvements in treatment, including the introduction of dialysis, have not changed the mortality rates of AKI. Further, hyperglycemia can be a significant problem in the trauma population and has been shown to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality, which is caused by a hypermetabolic response to stress and seems to be an entity of its own rather than simply a marker. More recent studies in the trauma population, while supporting the correlation between hyperglycemia and increased mortality, seemed to indicate that protocols aimed at moderate glucose control improved outcome while limiting the incidence of hypoglycemic complications.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] The present study was conducted to measure the distribution of laboratory values of performed investigations in Towards Improved Trauma Care Outcomes (TITCO) database and to understand whether these can play any role in predicting the outcome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

Data were from the TITCO project from India; the prospective, observational, multicenter trauma registry contains data of trauma patients admitted to four public university hospitals in Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata.[13] TITCO data were collected from the period from October 1, 2013, to September 30, 2015. Patient details of trauma cases were recorded by trained data collectors at each identified center of TITCO.

Study population

Patients from TITCO database with valid laboratory results of biochemical investigations were considered for this study. Cases with missing values of any biochemical investigation under consideration were excluded from further analysis. Patients presenting with a history of trauma and admitted or died after admission in study hospitals were included in the study. Patients with isolated limb injury and brought dead cases were excluded from the study. Biochemical investigations considered for this study are hemoglobin, hematocrit, random blood sugar, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and serum creatinine. Results of each of these investigations were categorized into normal, below normal range, or above normal range.[14] Gender-wise age group wise classification is made for respective variables. Overall mortality is considered as outcome variable.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis was used assuming overall mortality as dependent variable and corresponding biochemical investigation as independent variable with alpha level of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Considering normal range values of laboratory investigation as reference category, relative odds for above and below the normal range were estimated. Frequency chart of result values of each laboratory investigation was prepared. Cross-tabulation of gender-wise and age group-wise laboratory result was expressed as percent as well as actual numbers. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows and Microsoft Excel version 2016.

RESULTS

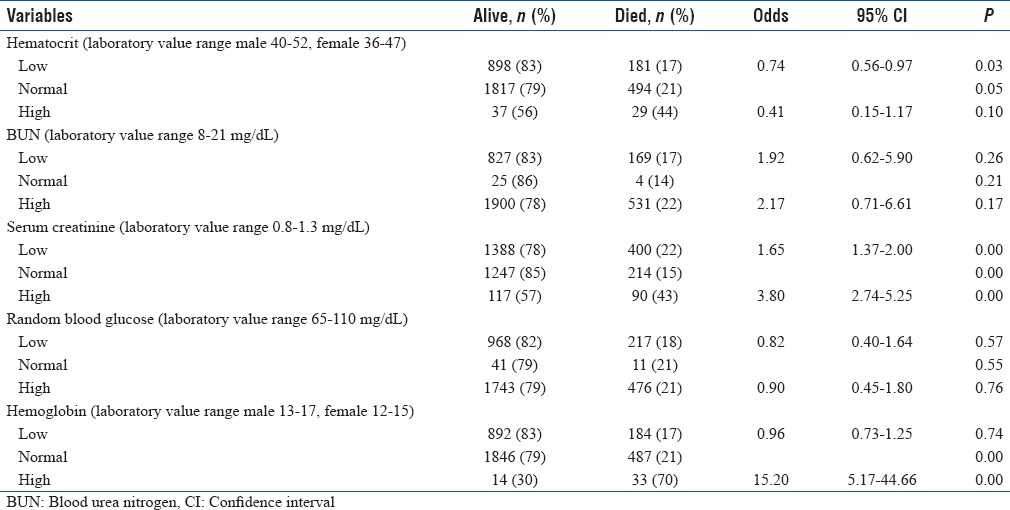

From TITCO registry, 3456 patients with valid real-time laboratory values of five biochemical investigations were considered for this study. Overall mortality reported in study population of trauma patient was 20.37%. Overall mortality among female was 29.13%, while in males, it was 17.33%. Age group-wise increase in mortality was found to be increasing from pediatric to adults and then adult to geriatric age group (>60 years) with percentages mortality as 13.12, 20.57 and 32.43% respectively. From the grouping of each of the laboratory results, it was found that overall higher values than normal range higher the proportion relative mortality. Among the patients with above normal range hematocrit, serum creatinine, and hemoglobin, mortality was observed 43.94, 43.48, and 70.21%, respectively. Among the patients with normal range of reported biochemical laboratory values, the overall morality was found in the range of 14%–21% for all five laboratory tests. Below the normal range, values of laboratory investigation were seen to be associated with mortality percentages of 17%–22% [Table 1] Diagnostic result values are seen to be associated with survival of trauma patients. For hemoglobin, serum creatinine, and BUN, relative odds for above normal values were found to be 15.20 (P < 0.001), 3.8 (P < 0.001), and 2.17 (P = 0.17), respectively. For lower values of all biochemical investigations, except serum creatinine and BUN, no statistically significant difference was found [Table 1].

Table 1.

Biochemical laboratory investigation-wise survival in trauma patients

DISCUSSION

The laboratory parameters that we considered are standardized between laboratories and hence objective and reliable. Abnormalities in some laboratory parameters may mainly be an expression of the degree of injury, but for other parameters, abnormalities may induce further damage or delay the recovery process.[15] The present study describes the laboratory parameters that are routinely determined on admission and their influence on the outcome following injury. The study reports that higher laboratories values of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and serum creatinine had higher rates of deaths among injury patients. For abnormal higher value of hemoglobin and serum creatinine, the relative significant odds were 15.2 and 3.8, respectively, as compared to normal range.

Hemoglobin

The present study reported that injury patients with higher level of hemoglobin were 15.2 times higher risk of death as compared with normal level of hemoglobin. Lower level of hemoglobin was not significant with outcome. Optimal hemoglobin level for predicting outcome among injured patients remains unknown.[16] A study has demonstrated that a mean 7-day hemoglobin concentration of <90 g/L may be harmful in patients with a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).[17] Patient outcomes after TBI are worse in patients with lower hemoglobin level.[18] Cerebral oxygen delivery is dependent upon the cerebral perfusion pressure and the oxygen content of blood, which is principally determined by hemoglobin. Neuronal tissue in injured patients is controversial with limited evidence to provide transfusion thresholds.[17]

Hematocrit

In our study, lower levels of Hematocrit were related with higher reported deaths, yet this relation was not significant. Trauma professional opined that a low hematocrit on the first blood drawn during trauma resuscitation is more helpful that previously thought. Be sure to check those laboratory values early, and if the hematocrit value is in the mid-30s or lower, start looking for significant sources of bleeding.[19] At Kings County Hospital Center, a Level I trauma center at New York, the serial hematocrit measurements are a routine part of the trauma evaluation for identifying volume loss as prognostic marker.[20]

A study at the Department of Emergency Medicine, Albany Medical College, New York, reported that the effect of hemodilution from intravenous fluid need to be critically thought to place hematocrit any prognostic value.[21] The researchers in the Department of Medicine, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, concluded that hematocrit levels may have some diagnostic utility during the early management of penetrating trauma. Presentation with an hematocrit below normal or an early decrease may be considered as an indicator of potential injury; lower the hematocrit, or the greater the decrease, the greater the probability that a significant injury.[22]

The study conducted at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine concluded that admission hematocrit correlated well with signs of shock and hemorrhage in trauma patients requiring emergency surgery because fluid shifts rapidly from the interstitial space into the vasculature.[23] Yet, other opinions are there regarding hematocrit and hemoglobin as mortality indicator after trauma. The research group from the Department of Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, has a new conceptual paradigm that hematocrit and hemoglobin behave as identical parameters and hematocrit levels are not different or even superior to hemoglobin. They proposed that there is no reason for determining both hematocrit and hemoglobin in trauma patients.[24]

Hemoglobin and hematocrit values remain unchanged from baseline immediately after acute blood loss. During resuscitation, the hematocrit may fall secondary to crystalloid infusion and re-equilibration of extracellular fluid into the intravascular space. In the absence of preexisting disease, transfusions can be withheld until significant clinical symptoms are present or the rate of hemorrhage is enough to indicate ongoing need for transfusion.[25]

Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen

In our study, we have observed that AKI happened for which the serum creatinine and BUN levels of trauma victims and odds ratio with mortality were related both for above and below normal values in both the variables. Chinese researchers have highlighted the importance of close surveillance of renal function and stressed the value of renal hygiene in the severe TBI cases.[26] The research group from Fortaleza city, northeast of Brazil, observed that AKI is a fatal complication after trauma, which presented with a high mortality in the studied population. The prevalence of AKI and overall mortality of their patients was higher than reported in literature. A better comprehension of factors associated with death in trauma-associated AKI is important, and more effective measures of the prevention and treatment of AKI in this population are urgently needed.[27]

Random blood glucose

In our study, we have observed that level of glucose in blood did not show any higher odds ratio in relation to mortality. Researchers are of strong opinion that blood glucose level seems to be more than simply a marker, but an entity of its own with a whole collection of adverse effects with blood glucose concentrations >200 mg/dl had a significantly increased mortality rates.[28]

Yendamuri et al. opined that blood glucose level on admission can be used as a valuable prognostic indicator in trauma patients.[29]

Scalea et al. assessed the impact of a tight glucose control regimen on outcome in critically injured trauma patients and demonstrated a survival benefit.[30] Literature supports blood glucose as an independent predictor of hospital mortality in regression analysis considering age, gender, injury severity, laboratory data, including serum potassium, pH, bicarbonate, pCO2, pO2, and lactate and prothrombin time.[31]

Tight glucose control during the acute phase with severe TBI has deleterious effects of presenting the injured brain with hyperglycemia without any clinical evidence to support high blood glucose levels worsens neurologic injury. Yet, of the current evidence-based medicine, researches do not support keeping blood glucose levels below 110–120 mg/dl during the acute care of patients with severe TBI with increasingly associated hypoglycemic sequels.[32]

There is, however, no consensus regarding optimal and safe glycemic target range has not been determined to implement during intervention in TBI patients, varying between individuals at different time points during the clinical course. This has lead us to disagreement on the best way to approach glycemic control.[33] Research group from Malaysia noted that the patients with isolated TBI and minimal increases in blood glucose levels were more likely to have a favorable outcome and concluded that hyperglycemia is an important independent predictor of outcome. They also suggested that tight control of blood glucose in patients with TBI may improve outcomes for these patients.[34]

In TBI with low Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) with hyperglycemia at an early stage may be a reliable marker of cerebral injury and prognosis as elevated blood glucose level may suggest that a patient's prognosis is likely poor and the risk of dying is substantially high.[35] Many studies have reported the prognostic value of clinical and radiological parameters in injury, but relatively few have investigated the relation between laboratory parameters on admission and outcome.[36]

Abnormalities in laboratory parameters frequently follow the injuries; analyses of these are routinely measured parameters has the prognostic value. Most importantly, abnormal values can be corrected by treatment, in contrast to demographics such as age or radiological parameters, which mainly reflect the severity of injury, namely, GCS, Glasgow Outcome Scale, and computerized tomography scan.[37] There are opposing opinions against battery of laboratory investigations in all trauma cases. Literature reported that 95% of the US Level I trauma centers perform costly routine laboratory testing of trauma patients, despite the paucity of supportive scientific data and rational guidelines for ordering tests in different levels of trauma care settings is the call of the day.[38] As resource utilization becomes increasingly scrutinized, the question remaining is whether any laboratory test battery should be recommended as a “routine protocol” across the entire spectrum of trauma patients.[39]

Strengths of the study

This was a prospective, observational registry where real-time assessments were done for better clinical outcomes of the trauma victims.

Limitations of the study

Laboratory investigations are one of these tools with multiple dependencies, which can be used to document the baseline values in vulnerable group and can be repeated to follow the progress to the treatment or any need for further interventions.[1,37] The present study uses one time value in assessing the impact of these values on patients. It is difficult to tell that the patients with abnormal were in good health before the injury as this has not been taken into consideration.

Future directions of the study

This study was novel in this part of country for a very important issue pertaining to biochemical laboratory parameters though this was conducted on small sample, so external validity will be limited. In future, multicentric, prospective, randomized, controlled trials are necessary to determine the optimal sampling for supportive evidences from biochemical laboratory values and treatment paradigm for nationally representative clinical practice guidelines.

CONCLUSION

Laboratory parameters can be an important admission parameter in trauma patients. With our limited resources, it will be wiser to all the investigations in all the patients. We need to categorize investigations into screening and based on findings further investigations. This study describes the association of laboratory parameters in trauma patient with their overall mortality in Indian settings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all the trauma victims and their caregivers who volunteered for their sincere participation to complete the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson DW, Rudehill A, MacCallum RM, Holst A, Wanecek M, Weitzberg E, et al. Multivariate outcome prediction in traumatic brain injury with focus on laboratory values. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:2613–24. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotton BA, Beckert BW, Smith MK, Burd RS. The utility of clinical and laboratory data for predicting intraabdominal injury among children. J Trauma. 2004;56:1068–74. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000082153.38386.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes JF, Sokolove PE, Brant WE, Palchak MJ, Vance CW, Owings JT, et al. Identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:500–9. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant MS, Tepas JJ, 3rd, Talbert JL, Mollitt DL. Impact of emergency room laboratory studies on the ultimate triage and disposition of the injured child. Am Surg. 1988;54:209–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford EG, Karamanoukian HL, McGrath N, Mahour GH. Emergency center laboratory evaluation of pediatric trauma victims. Am Surg. 1990;56:752–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankel HL, Rozycki GS, Ochsner MG, McCabe JE, Harviel JD, Jeng JC, et al. Minimizing admission laboratory testing in trauma patients: Use of a microanalyzer. J Trauma. 1994;37:728–36. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isaacman DJ, Scarfone RJ, Kost SI, Gochman RF, Davis HW, Bernardo LM, et al. Utility of routine laboratory testing for detecting intra-abdominal injury in the pediatric trauma patient. Pediatrics. 1993;92:691–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namias N, McKenney MG, Martin LC. Utility of admission chemistry and coagulation profiles in trauma patients: A reappraisal of traditional practice. J Trauma. 1996;41:21–5. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199607000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parish RA, Watson M, Rivara FP. Why obtain arterial blood gases, chest x-rays, and clotting studies in injured children? Experience in a regional trauma center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1986;2:218–21. doi: 10.1097/00006565-198612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capraro AJ, Mooney D, Waltzman ML. The use of routine laboratory studies as screening tools in pediatric abdominal trauma. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:480–4. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000227381.61390.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abramson N, Melton B. Leukocytosis: Basics of clinical assessment. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2053–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilmore DW. Carbohydrate metabolism in trauma. Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;5:731–45. doi: 10.1016/s0300-595x(76)80048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy N, Gerdin M, Ghosh S, Gupta A, Kumar V, Khajanchi M, et al. 30-day in-hospital trauma mortality in four Urban university hospitals using an Indian trauma registry. World J Surg. 2016;40:1299–307. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3452-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lab Values, Normal Adult: Laboratory Reference Ranges in Healthy Adults. [Last accessed on 2016 Oct 26]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2172316-overview .

- 15.Margulies DR, Hiatt JR, Vinson D, Jr, Shabot MM. Relationship of hyperglycemia and severity of illness to neurologic outcome in head injury patients. Am Surg. 1994;60:387–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desjardins P, Turgeon AF, Tremblay MH, Lauzier F, Zarychanski R, Boutin A, et al. Hemoglobin levels and transfusions in neurocritically ill patients: A systematic review of comparative studies. Crit Care. 2012;16:R54. doi: 10.1186/cc11293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sekhon MS, McLean N, Henderson WR, Chittock DR, Griesdale DE. Association of hemoglobin concentration and mortality in critically ill patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2012;16:R128. doi: 10.1186/cc11431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Litofsky NS, Martin S, Diaz J, Ge B, Petroski G, Miller DC, et al. The negative impact of anemia in outcome from traumatic brain injury. World Neurosurg. 2016;90:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.02.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGonigal M. The Trauma Professional's Blog AAST 2011: The Initial Hematocrit Matters. [Last accessed on 2017 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.regionstraumapro.com/post/9876948370 .

- 20.Goldman M, Kapitanyan R, Zehtabchi S, Sinert R, Ballas J. Operating characteristics of serial hematocrit measurements in detecting major injury after trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:S128. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder HS. Significance of the initial spun hematocrit in trauma patients. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:150–3. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paradis NA, Balter S, Davison CM, Simon G, Rose M. Hematocrit as a predictor of significant injury after penetrating trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 1997;15:224–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(97)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan ML, Thorson CM, Otero CA, Vu T, Schulman CI, Livingstone AS, et al. Initial hematocrit in trauma: A paradigm shift? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:54–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823d0f35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nijboer JM, van der Horst IC, Hendriks HG, ten Duis HJ, Nijsten MW. Myth or reality: Hematocrit and hemoglobin differ in trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:1310–2. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180341f54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Udeani J. Hemorrhagic Shock Workup. [Last accessed on 2017 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/article/432650-workup .

- 26.Li N, Zhao WG, Zhang WF. Acute kidney injury in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: Implementation of the acute kidney injury network stage system. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14:377–81. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9511-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Abreu KL, Silva Júnior GB, Barreto AG, Melo FM, Oliveira BB, Mota RM, et al. Acute kidney injury after trauma: Prevalence, clinical characteristics and RIFLE classification. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2010;14:121–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.74170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eakins J. Blood glucose control in the trauma patient. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:1373–6. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yendamuri S, Fulda GJ, Tinkoff GH. Admission hyperglycemia as a prognostic indicator in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;55:33–8. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000074434.39928.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scalea TM, Bochicchio GV, Bochicchio KM, Johnson SB, Joshi M, Pyle A, et al. Tight glycemic control in critically injured trauma patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:605–10. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreutziger J, Wenzel V, Kurz A, Constantinescu MA. Admission blood glucose is an independent predictive factor for hospital mortality in polytraumatised patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1234–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1446-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marion DW. Optimum serum glucose levels for patients with severe traumatic brain injury. F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:pii: 42. doi: 10.3410/M1-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi J, Dong B, Mao Y, Guan W, Cao J, Zhu R, et al. Review: Traumatic brain injury and hyperglycemia, a potentially modifiable risk factor. Oncotarget. 2016;7:71052–61. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harun Haron R, Imran MK, Haspani MS. An observational study of blood glucose levels during admission and 24 hours post-operation in a sample of patients with traumatic injury in a hospital in Kuala Lumpur. Malays J Med Sci. 2011;18:69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danisman B, Yilmaz MS, Isik B, Kavalci C, Yel C, Solakoglu AG, et al. Analysis of the correlation between blood glucose level and prognosis in patients younger than 18 years of age who had head trauma. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:8. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0010-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Beek JG, Mushkudiani NA, Steyerberg EW, Butcher I, McHugh GS, Lu J, et al. Prognostic value of admission laboratory parameters in traumatic brain injury: Results from the IMPACT study. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:315–28. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Helmy A, Timofeev I, Palmer CR, Gore A, Menon DK, Hutchinson PJ, et al. Hierarchical log linear analysis of admission blood parameters and clinical outcome following traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010;152:953–7. doi: 10.1007/s00701-009-0584-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burton J, Wolfson A, Rockoff S. Routine laboratory testing in emergency department trauma patients at Level 1 trauma centers: A national survey. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:408. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Asimos AW. The Trauma Panel: Laboratory Test Utilization in the Initial Evaluation of Trauma Patients. [Last accessed on 2017 Oct 26]. Available from: http://www.ahcmedia.com/articles/56431-the-trauma-panel-laboratory-test-utilization-in-the-initial-evaluation-of-trauma .