Abstract

Background:

The cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in prone position has been dealt with in 2010 American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines but have not been reviewed in 2015 guidelines. The guidelines for patients presenting with cardiac arrest under general anesthesia in lateral decubitus position and regarding resuscitation in confined spaces like airplanes are also not available in AHA guidelines. This article is an attempt to highlight the techniques adopted for resuscitation in these unusual situations.

Aims:

This study aims to find out the methodology and efficacy in nonconventional CPR approaches such as CPR in prone, CPR in lateral position, and CPR in confined spaces.

Methods:

We conducted a literature search using MeSH search strings such as CPR + Prone position, CPR + lateral Position, and CPR + confined spaces.

Results:

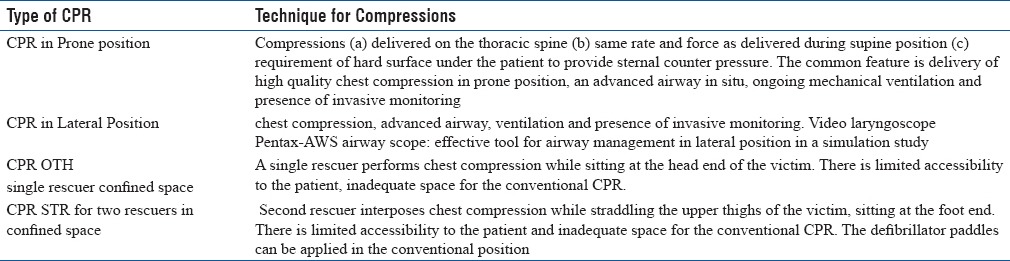

No randomized controlled trials are available. The literature search gives a handful of case reports, some simulation- and manikin-based studies but none can qualify for class I evidence. The successful outcome of CPR performed in prone position has shown compressions delivered on the thoracic spine with the same rate and force as they were delivered during supine position. A hard surface is required under the patient to provide uniform force and sternal counter pressure. Two rescuer technique for providing successful chest compression in lateral position has been documented in the few case reports published. Over the head CPR and straddle (STR), CPR has been utilized for CPR in confined spaces. Ventilation in operating rooms was taken care by an advanced airway in situ.

Conclusion:

A large number of studies of high quality are required to be conducted to determine the efficacy of CPR in such positions.

Keywords: Active compression decompression device, basic life support, cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, lateral decubitus position, prone

INTRODUCTION

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a series of lifesaving actions, to support and maintain breathing and circulation for an infant, child or adult who has had a cardiac or respiratory arrest, thereby improving the chances of survival. CPR includes the manual application of chest compressions and ventilations to patients in cardiac arrest, done in an effort to maintain viability until advanced help arrives. This procedure is basic component of basic life support (BLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS).

References of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation have been found in Biblical literature; the Old Testament describes resuscitation in the books of Kings, where the Hebrew Prophet Elijah performed the assumed first documented case of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation (Prophet Elijah warms the dead boy's body and “places his mouth over his…”).[1]

In 1740, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation of drowning victims was officially recommended by the Paris Academy of Sciences. Dr Friedrich Maass in 1891, performed the first ever documented chest compression.[2,3] It was scientifically demonstrated by Peter Safar and James Elan in 1956. Cardiologist Leonard Scherlis started American Heart Association's (AHA) CPR committee in 1963 and thereafter CPR was formally endorsed by AHA. The year 1972 witnessed the first mass training for CPR in Seattle, Washington. In 1979 at the third National Conference on CPR, ACLS was formally introduced.[2,3] The International Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) was founded in 1992. The international guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiac care (ECC) were formulated for the first time in 1999. Since then, periodic revisions of the AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC are done by a multitude of agencies on the available scientific evidence. The 2015 ILCOR-guided AHA guidelines are an update to the 2010 International Consensus on CPR and ECC science with treatment recommendations.[4]

The latest Resuscitation guidelines cover not only the routine but also several special situations such as cardiac arrest associated with pregnancy, pulmonary embolism, asthma, anaphylaxis, morbid obesity, electrolyte imbalance, trauma, accidental hypothermia, avalanche, cardiac arrest due to drowning, electric shocks or lightning, during percutaneous coronary intervention, cardiac tamponade, cardiac surgery and cardiac or respiratory arrest due to opioid overdose or poisoning due to benzodiazepines, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, cocaine, cyclic antidepressants, carbon monoxide, and cyanide.[4] European Resuscitation Council and AHA also published updated guidelines on traumatic cardiac arrest in 2015.[5,6] Typically, the guidelines on performance of CPR assume the patient to be in supine position, immobilized on a hard and stable surface.

CPR has gradually evolved from a relatively crude technique to its current form. The technique for delivery of chest compressions and ventilation has been improved according to evidence-based guidelines. Research has been performed to understand the complex physiology of cardiocerebral circulation developed with the correct CPR technique. The reversible cause of cardiac arrest such as cardiac dysrhythmias, pulmonary emboli, hypoxia, trauma, hypovolemia due to hemorrhage, and drug overdose, require restoration of cardiac and cerebral circulation at the earliest for recovery. The critical step is to generate enough aortic pressure so as to restore circulation. The optimally performed compression phase in a conventional CPR manages to increase the intrathoracic pressure, squeezing the heart between the sternum and the vertebrae, thus propelling the blood forward from the arrested heart towards the coronaries and brain. On the basis of available evidence from preclinical and clinical studies, AHA recommends a rate of 100–120/min for chest compressions, depth of at least 5 cm, adequate chest recoil, minimum interruptions in chest compression and 8–10 breath/min for a high-quality CPR. Chest compression at inadequate rate and depth with insufficient recoil leads to unfavorable clinical outcomes. AHA recommends a compression-ventilation ratio of 30:2 for BLS, continuous chest compressions at a rate of 100–120/min with asynchronous ventilation every 6 s if an advanced airway is in place for advanced life support. Ventilation volume advised is around 8 ml per kg so as to avoid hyperventilation and minimize CPR-induced ventilation perfusion mismatch.[4] Defibrillators form an integral part of BLS and ACLS for those patients who present with a shockable rhythm such as ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT).[4] However, the incidence of VF has declined over past two decades, and now the incidence of VF is around 20% to 35% of all the out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).[7] Hence, the emphasis lies on effective chest compression, adequate ventilation, and early defibrillation if required for a successful outcome or return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

However, in certain scenarios, patient requiring CPR may be in a position other than supine or be on an unstable surface. There is a lack of guidelines on techniques for performing CPR in such situations, probably because they are rather unusual and occur not very frequently. These are the situations when patients are in prone or lateral positions, under general anesthesia in operating rooms (OR), undergoing surgeries, and suffer cardiac arrest. The preferred option is to turn the patient supine[4] and perform CPR but sometimes exercising this option becomes difficult due to various patient fixing devices and the exposed surgical field. The danger of losing precious time in the process of turning patient supine is also a deterrent.

When a patient suffers from cardiac arrest in confined spaces such as air planes, submarines, or in computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suites, or during intrahospital transfer, performing an effective CPR in the limited space available or on patient transport trolley in the conventional manner is quite challenging. Thus, we conducted a literature search to identify various ways for delivering CPR in unusual positions which could be of interest to practicing anesthesiologists.

METHODS

The aim of this study was to find out the methodology and efficacy in nonconventional CPR approaches such as CPR in prone, CPR in lateral position, and CPR in confined spaces.

The objective of this study was to find out the number of studies conducted for the nonconventional CPR, methodology used and outcome in terms of ROSC.

A literature search was performed using PubMed central, utilizing MeSH search strings CPR + lateral position; CPR + prone position; over the head (OTH) + CPR; CPR + confined spaces.

Inclusion criteria

Studies, case reports, commentaries which dealt with CPR in prone position, lateral position, and CPR in confined spaces.

Exclusion criteria

Studies where CPR was not related to prone position, lateral position or where CPR was not related to confined spaces in the results obtained were excluded from our study.

RESULTS

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in prone position

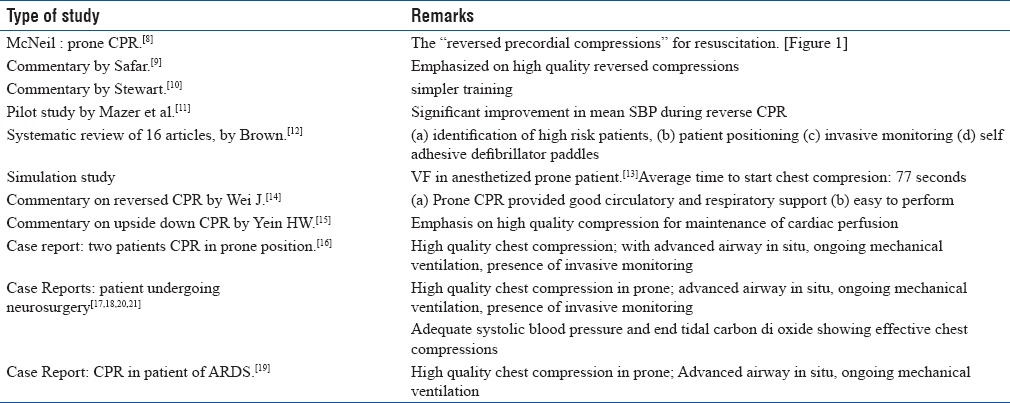

Prone CPR may be performed in the OR during cardiac arrest occurring in cases undergoing spine surgery, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, or other surgical procedures on the back. The requirement may also arise in some situations in the ICU, where critically ill patients with sepsis or ARDS arrest while being mechanically ventilated, in prone position. Compressions in prone position were delivered on the thoracic spine with the same rate and force as they were delivered during supine position. A hard surface is required under the patient so as to provide uniform force and sternal counter pressure and this is called as reversed precordial compressions [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Patient in prone position and the rescuer providing “Reversed Precordial Compressions”

A total of 19 results were retrieved after PUBMED central search for MeSH search strings CPR + prone position. Five results deliberated on recovery position and sleep related seizure with sudden death and hence they were not included in this study. The rest of the results have been discussed in Table 1.

Table 1.

CPR in Prone Position

The AHA Guidelines for CPR of the year 2010, document that when patient cannot be placed supine than it may be reasonable for the rescuers to give CPR in prone position, particularly in hospitalized patients with an advanced airway in place (Class IIb, Level of evidence C). These were not reviewed in the 2015 guidelines.

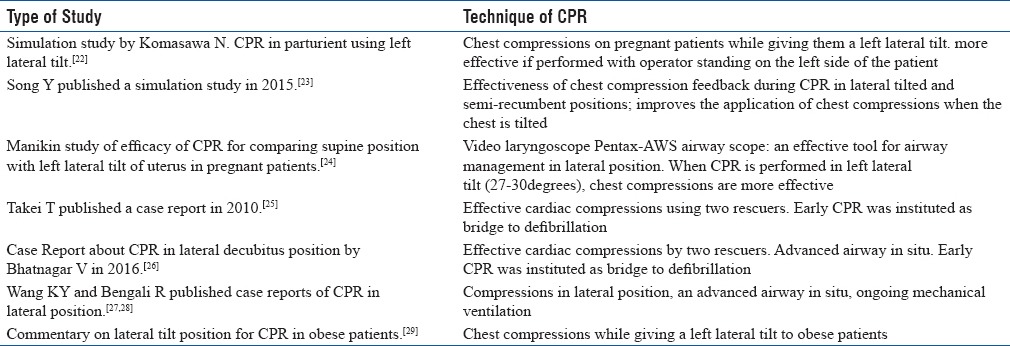

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in lateral position

Lateral position is sometimes required for patients undergoing neurosurgery, surgery on kidneys, or upper or lower limbs. In general, these patients are in the OR and may/may not have an advanced airway in situ. CPR on pregnant women of gestation age more than 20 weeks also require a lateral tilt so as to prevent compromise of venous return due to gravid uterus compressing inferior vena cava and descending aorta. Some of the patients in lateral position intraoperatively have an application of thorax fixing or skull fixing devices which make it difficult to turn the patient supine for performing CPR.

Seventeen results were obtained on PubMed search for Mesh search strings CPR + lateral position, out of which nine results were not considered because they did not relate to CPR in lateral position. The rest of the results are discussed in Table 2.

Table 2.

CPR in Lateral Position

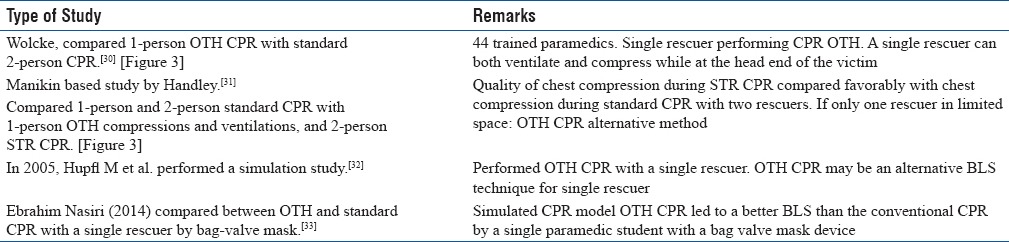

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in confined spaces

Confined spaces such as CT/MRI suites, airplanes, ships, and submarines make conventional CPR difficult due to paucity of space for the rescuer.

On performing PUBMED search for CPR + confined spaces brought forth nil results. PUBMED search for OTH + CPR gave 20 results out of which only two were relevant. We found few studies on Google search for OTH CPR. The results have been depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Over the Head (OTH) and Straddle (STR) CPR

DISCUSSION

CPR in prone position or lateral position is a not very common scenario, and hence little attention has been given to these situations, but these kind of scenarios are not very rare for neuroanesthesiologists and intensivists. This could be the reason for lack of randomized control trials in any of the areas discussed above. The number of articles published is too small to comment on the efficacy of the approach to CPR. Although some simulation- and manikin-based studies are available, but greater number of such studies is required to delineate the precise procedure and overcome the various challenges in prone and lateral position resuscitation. Similarly, simulation- and manikin-based studies for performing CPR for interhospital patient transfer would be required for any strong consensus regarding the effective procedure.

McNeil (1989) was first to propose prone CPR in 1989 followed by Safar in 1990.[8,9] Stewart in 2002 claimed the advantages of prone CPR as simpler training and increased likelihood of actual performance by the bystanders.[10] Pilot study by Mazer et al. in 2003 on six patients who were given 15 additional minutes of standard CPR followed by 15 min of reverse CPR highlighted significant improvement in mean SBP during reverse CPR from 48 mm of Hg to 72 mm of Hg.[11] First systematic review of 16 articles was performed by Brown et al. in 2001. He enrolled a total of 22 intubated hospitalized patients out of which ten patients survived to discharge. He noticed that improved recovery depended on (a) identification of high-risk patients, (b) careful patient positioning, (c) use of invasive monitoring, and (d) placement of self-adhesive defibrillator paddles.[12]

A simulation study for cardiac arrest due to VF in anesthetized prone pediatric patient was conducted on anesthesia residents in recognizing and treating VF in prone patients and concluded that additional training is required for correct identification of VF in prone position.[13] Commentary on reversed CPR by Wei J and then by Yein HW emphasized on high-quality chest compressions and proclaimed that Prone CPR provided good circulatory and respiratory support and was easy to perform.[14,15]

There were six case reports of successful CPR in prone position on various adult patients undergoing neurosurgeries and surgeries on spine.[16,17,18,19,20,21] The common feature in all these case reports is delivery of high-quality chest compression in prone position, an advanced airway in situ, ongoing mechanical ventilation and presence of invasive monitoring.

The return ROSC was noted at time intervals from 2 min to 11 min in all these case reports and there were nil neurological deficits noted in the resuscitated patients. It seems a logical conclusion that high-quality chest compressions in the prone position were able to generate sufficient cardiac output so as to translate into successful resuscitation.

Limited number of case reports which have been found for CPR in prone position have brought out certain points to light. First being, most of the cases pertained to cardiac arrest in hospital; second point is that they had an advanced airway already secured and ongoing mechanical ventilation. Compressions were delivered on back while counter pressure on sternum was provided. The rate of compressions was 100–120/min, with adequate chest recoil and depth. Counter sternal pressure from a solid surface is required for effective and high-quality chest compressions.

What we can suggest is that as soon as CPR is initiated, any surgical instruments from surgical site should be removed. The wound should be packed to reduce blood loss. If the patient's head is fixed in pins, an assistant should support the head to prevent any injuries. Delivering effective chest compressions may be difficult when the patients are positioned prone with the help of frames like Wilson or Relton Hall. These frames are utilized to allow free movement of chest and abdomen and prevention of any obstruction to venous return during surgery. Defibrillator paddles can be applied in bi-axillary positions or posterolateral position (one paddle in the left mid-axillary line while the second one over the right scapula).

Simulation study was conducted by Komasawa N in 2015 for CPR in parturient using left lateral tilt and it was concluded that chest compressions: more effective if performed with operator standing on the left side of the patient.[22] Song Y published a simulation study in 2015 for evaluating the effectiveness of chest compression feedback during CPR in lateral tilted and semi-recumbent positions and found that feedback device improves the application of chest compressions when the chest is tilted.[23]

Manikin study was conducted for efficacy of CPR to compare supine position with left lateral tilt of uterus in pregnant patients, and it was concluded that CPR with left lateral tilt was effective.[24]

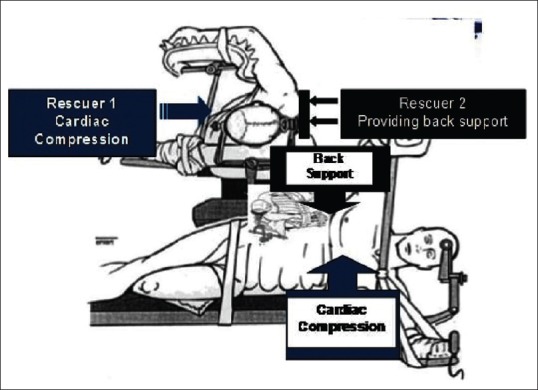

Four case reports were published by different authors about successful resuscitation in lateral position for patients undergoing neurosurgery or surgery on spine, all with a definitive airway in situ and ongoing mechanical ventilation. Authors in their individual case reports emphasized on effective chest compression utilizing two rescuers, one delivering chest compression while other providing mechanical support for uniform distribution of compressive force.[25,26,27,28] The ROSC took place from 2 min to 5 min. All the patients were resuscitated without any neurological deficit.

Thus, it is highlighted that chest compression in the lateral position by two rescuers, one applying compressions on the chest while the other mechanically supporting the back is a resuscitation maneuver for performing CPR in lateral position [Figure 2]. The defibrillators paddles can be placed in anteroposterior position; one paddle on the left precordium and the other just inferior to the left scapula.[26] Ongoing mechanical ventilation with an advanced airway in place was helpful in ventilation, but video laryngoscope can show some promise for airway management in lateral position.[29] Invasive monitoring with arterial blood pressure monitoring and end tidal carbon di oxide monitoring could help in assessment of efficacy of ventilation. If chest compressions are ineffective or quality of CPR is poor during the CPR in prone or lateral position, then all efforts should be made to turn the patient supine and continue the CPR.

Figure 2.

Patient in lateral position and rescuer one providing chest compression while rescuer two provides back support

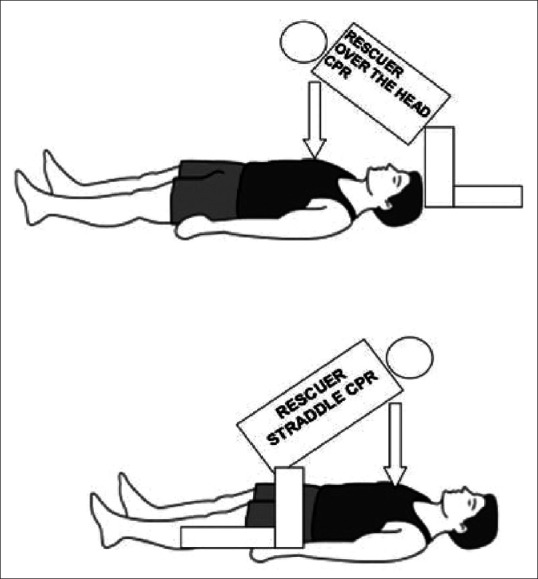

OTH CPR in single rescuer while OTH and STR CPR with two rescuers have shown promising results in the few studies which were found.[30,31,32,33] We also speculate that OTH and STR CPR can be utilized for performing CPR while the patient is being transported on a cart, which is different from a hospital bed [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

“Over the Head” cardiopulmonary resuscitation by single rescuer and “Straddle” cardiopulmonary resuscitation when two rescuers are present. Chest compressions are given by rescuer in straddle position while leaving the head end for providing space to rescuer giving ventilation

No literature could be found for delivery of CPR during interhospital patient transfer. The techniques of OTH CPR and STR CPR can be utilized for the patients being transported on trolley/carts who suffer a cardiac arrest. The single rescuer sits at the head end of the patient and provides chest compressions as well as ventilation with bag valve mask. If two rescuers are present, then the chest compressions can be provided with the help of STR CPR and ventilations can be provided by the second rescuer from the head end. Originally, the techniques of OTH CPR and STR CPR were described for executing CPR in confined spaces, thus they can be successfully utilized to deliver effective CPR in patients suffering from cardiac arrests in MRI or CT suites. These patients are on a hard surface, but there is limited accessibility to the patient and inadequate space for the conventional CPR to be delivered from the side. The defibrillator paddles can be applied in the conventional position, but difficulty may be encountered for monitoring of the patient.

Active Compression and Decompression Device (ACDD)-assisted CPR show promise in resuscitation in OHCA scenarios.[34,35,36] They can also be utilized for cardiac arrest patients being transported on carts. These devices however, cannot be utilized during cardiac arrest in prone or lateral position in patients undergoing surgery due to risk of contamination of the exposed sterile surgical field and difficulty in application. Moreover, the use of ACDD may not be a very feasible option due to various patients fixing devices while the patient is in prone or lateral decubitus position, thereby leaving little space for the application of the device. Losing precious time during the application of such devices is also deterrent to application of these devices in these positions.

Based on the gathered literature, observations have been summarized in a consolidated manner in Table 4.

Table 4.

Lessons Learnt

CONCLUSION

A very limited number of studies are available in the nonconventional scenarios requiring CPR as discussed above. It is extremely difficult task to deduct methodology for compressions and ventilation, complications if any, chances of survival and scope of improvement from this limited number of studies. It is reflected that cardiac arrest in any scenario requires a team effort and multifaceted approach based on physiology and evidence. Planning and conduct of more simulation studies, manikin-based studies, feedback mechanisms to assure effective placement of hands for compression, optimal rate, depth and full recoil in the unusual positions requiring nonconventional CPR should be undertaken. Airway management also seems an uphill task during CPR in prone or lateral position, but larger number of studies utilizing video laryngoscopes should be undertaken to assess the feasibility.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sternbach GL, Varon J, Fromm RE. Resuscitation in the bible. Crit Care Shock. 2002;2:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermreck AS. The history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Surg. 1988;156:430–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBard ML. The history of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:273–5. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(80)80389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care; 2010 and 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherren PB, Reid C, Habig K, Burns BJ. Algorithm for the resuscitation of traumatic cardiac arrest patients in a physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical service. Crit Care. 2013;17:308. doi: 10.1186/cc12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truhlář A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GE, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJ, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: Section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148–201. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aufderheide TP, Frascone RJ, Wayne MA, Mahoney BD, Swor RA, Domeier RM, et al. Standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus active compression-decompression cardiopulmonary resuscitation with augmentation of negative intrathoracic pressure for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomized trial. Lancet. 2011;377:301–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeil EL. Prone CPR aboard aircraft (McNeil method) J Emerg Nurs. 1994;20:446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safar P, Bircher NG. “Re-evaluation” of CPR. Resuscitation. 1990;20:79–81. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(90)90089-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart JA. Resuscitating an idea: Prone CPR. Resuscitation. 2002;54:231–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(02)00145-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazer SP, Weisfeldt M, Bai D, Cardinale C, Arora R, Ma C, et al. Reverse CPR: A pilot study of CPR in the prone position. Resuscitation. 2003;57:279–85. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(03)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown J, Rogers J, Soar J. Cardiac arrest during surgery and ventilation in the prone position: A case report and systematic review. Resuscitation. 2001;50:233–8. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tofil NM, Dollar J, Zinkan L, Youngblood AQ, Peterson DT, White ML, et al. Performance of anesthesia residents during a simulated prone ventricular fibrillation arrest in an anesthetized pediatric patient. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24:940–4. doi: 10.1111/pan.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei J, Tung D, Sue SH, Wu SV, Chuang YC, Chang CY, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in prone position: A simplified method for outpatients. J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:202–6. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yien HW. Is the upside-down position better in cardiopulmonary resuscitation? J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:199–201. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(09)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun WZ, Huang FY, Kung KL, Fan SZ, Chen TL. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation of two patients in the prone position using reversed precordial compression. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:202–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199207000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor JC, Buchanan CC, Rumball MJ. Cardiac arrest during craniotomy in prone position. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2013;3:224–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooney N. Prone CPR for transient asystole during lumbosacral spinal surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2010;38:212–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haffner E, Sostarich AM, Fösel T. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation in prone position. Anaesthesist. 2010;59:1099–101. doi: 10.1007/s00101-010-1785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelleher A, Mackersie A. Cardiac arrest and resuscitation of a 6-month old achondroplastic baby undergoing neurosurgery in the prone position. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:348–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Souza Gomes D, Alves Bersot CD. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the prone position. Open J Anesthesiol. 2012;2:199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komasawa N, Fujiwara S, Majima N, Minami T. New insights into maternal cardiopulmonary resuscitation – Significance of simulation research and training. Masui. 2015;64:864–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song Y, Oh J, Chee Y, Cho Y, Lee S, Lim TH, et al. Effectiveness of chest compression feedback during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in lateral tilted and semirecumbent positions: A randomised controlled simulation study. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:1235–41. doi: 10.1111/anae.13222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butcher M, Ip J, Bushby D, Yentis SM. Efficacy of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the supine position with manual displacement of the uterus vs. lateral tilt using a firm wedge: A manikin study. Anaesthesia. 2014;69:868–71. doi: 10.1111/anae.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takei T, Nakazawa K, Ishikawa S, Uchida T, Makita K. Cardiac arrest in the left lateral decubitus position and extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation during neurosurgery: A case report. J Anesth. 2010;24:447–51. doi: 10.1007/s00540-010-0911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatnagar V, Jinjil K, Raj P. Complete recovery after cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the lateral decubitus position: A report of two cases. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10:365–6. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.174921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang KY, Yeh YC, Jean WH, Fan SZ. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the lateral position for an infant with an anterior mediastinal mass. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2009;47:40–3. doi: 10.1016/S1875-4597(09)60020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bengali R, Janik LS, Kurtz M, McGovern F, Jiang Y. Successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the lateral position during intraoperative cardiac arrest. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1046–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182923eb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarthy T, Sharpe P. Lateral tilt position for obese patients. Resuscitation. 2009;80:385. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolcke BB, Gliwitsky B, Kohlmann T, Holcombe PA. Overhead-CPR versus standard-CPR in a two rescuer-ALS scenario. Resuscitation. 2002;55:116. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handley AJ, Handley JA. Performing chest compressions in a confined space. Resuscitation. 2004;61:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hüpfl M, Duma A, Uray T, Maier C, Fiegl N, Bogner N, et al. Over-the-head cardiopulmonary resuscitation improves efficacy in basic life support performed by professional medical personnel with a single rescuer: A simulation study. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:200–5. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000154305.70984.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nasiri E, Nasiri R. A comparison between over-the-head and lateral cardiopulmonary resuscitation with a single rescuer by bag-valve mask. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:30–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.125923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lurie K. Mechanical devices for cardiopulmonary resuscitation: An update. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2002;20:771–84. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Wang D, Yu Y, Zhao X, Jing X. Mechanical versus manual chest compressions for cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:10. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0202-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perkins GD, Brace S, Gates S. Mechanical chest-compression devices: Current and future roles. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:203–10. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328339cf59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]