Abstract

Treating pathological defects that are caused by resorption in teeth can be challenging. The task is complicated further if the resorption extends beyond the restrains of the root. The aim of this report is to describe a case of extensive internal tunneling resorption (ITR) associated with invasive cervical resorption (ICR) in a maxillary right lateral incisor and its nonsurgical treatment. A 22-year-old male was referred to the department of endodontics with a chief complaint of discolored maxillary right lateral incisor or tooth 12 and a history of trauma. An extensive ITR associated with ICR accompanied by apical periodontitis was detected on a preoperative radiograph which was confirmed on a cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) scan in a maxillary lateral incisor. After chemomechanical debridement and withdrawal of a separated file in the canal, calcium hydroxide was placed as an intracanal medicament for 2 weeks. Biodentine (BD) was used to obturate the defect as well as entire root canal system and to restore ICR. On a 5-year follow-up, the tooth was functional, and periapical healing was evident. Based on results of this case, successful repair of ITR associated with ICR with BD may lead to resolution of apical periodontitis. Trauma to teeth may lead to resorption which may be internal, external, and or a combination of both which may be asymptomatic in some patients. Preoperative assessment using CBCT imaging achieves visualization of location and extents of resorptive defects. Bioactive materials like BD may lead to favorable results in treating such extensive defects.

Keywords: Dental trauma, endodontic files, endodontics, replacement resorption

INTRODUCTION

Internal tunneling resorption (ITR) is a variant of internal root canal replacement resorption.[1] ITR exhibits irregular enlargement of the pulp chamber with disrupted canal space on a radiograph.[2] ITR channels into adjacent dentin from the root canal along with simultaneous irregular deposition of bone-like material. ICR presents with destruction of cementum and diagnosis might be made when the lesion is extensive due to lack of symptoms. Extensive resorptive defects may have a combination of ITR and ICR.[1]

Occurrence of ITR associated with ICR follows necrosis of pulp tissue. Hence, nonsurgical root canal therapy is the treatment of choice as it ceases the destructive resorptive process.[3] The irregularities caused by disruption and deposition pose difficulty in debridement of the root canal space. The use of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) will provide a three-dimensional (3D) image of the resorptive defect and adjacent structures aiding in decision-making toward amenable endodontic therapy.[4]

If the ITR extends to the external root surface, the integrity of the root is lost, and periodontal tissue destruction occurs. Biodentine (BD) introduced by Septodont is a bioactive calcium-silicate-based formulation which promises a bioactive behavior with high-mechanical properties and excellent biocompatibity. Its endodontic applications are similar to mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA), but is better suited because of its superior clinical consistency and setting time of 12 min.[5,6]

CASE REPORTS

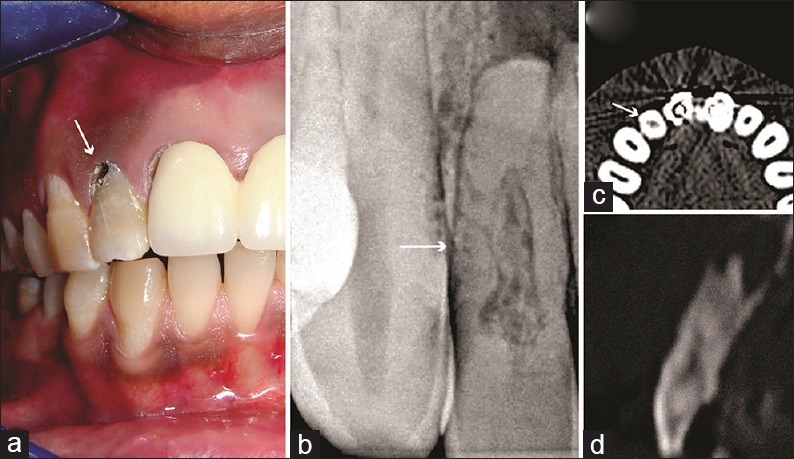

A 22-year-old male was referred to the department of endodontics with a chief complaint of discolored maxillary right lateral incisor. The patient had a history of trauma due to fall 12 years back. Clinical examination revealed discolored maxillary right lateral incisor tooth 12 with a defect at a cervical third region [Figure 1a]. Tooth 12 was unresponsive to cold test and electric pulp testing.

Figure 1.

(a) A preoperative photograph of tooth 12 showing discolored tooth 12 with a defect at cervical third region (arrow). (b) A preoperative radiograph suggestive of obliterated coronal pulp chamber and enlarged space and concomitant calcific depositions with middle-third of root canal (arrow). (c) The axial section at the level of middle-third of root reveals internal root resorption (arrow). (d) The sagittal section revealed a resorptive defect with concomitant radiopaque deposition

Radiographic examination revealed periapical radiolucency in relation to tooth 12. The coronal pulp chamber was obliterated and middle third of root canal presented with enlarged space and concomitant calcific depositions [Figure 1b]. To obtain specific knowledge about the 3D anatomy, patient was referred for a CBCT analysis.

CBCT analysis (Kodak 9500 Cone Beam 3D system, USA) of tooth 12 was done using field of view 5 × 5 and axial, sagittal, and horizontal sections were obtained [Figure 1c-d]. These images confirmed destruction and the enlargement of the pulp chamber and radiopaque deposition in the middle-third of the root extending to the external root surface apically. The ICR was evident at cervical area with shallow penetration in dentine. It appeared as if the resorption had tunneled into the dentin and scattered deposition of radiopaque material has taken place; hence, it was diagnosed as ITR, a variant of internal replacement root resorption associated with ICR, a type of external inflammatory resorption.

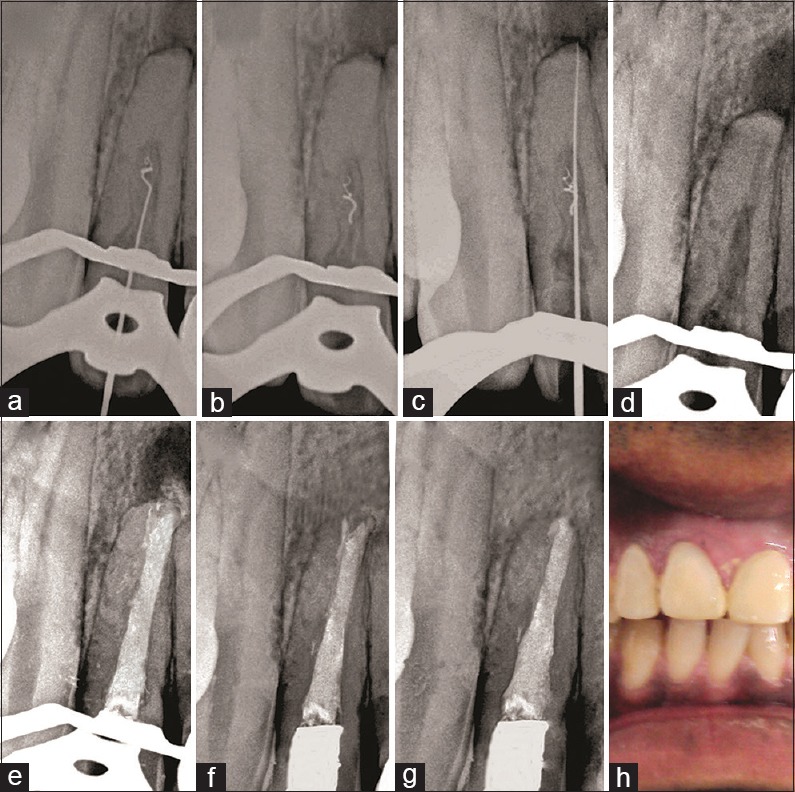

Nonsurgical endodontic treatment was planned in relation to tooth 12. Following application of rubber dam, a conventional access opening was made under magnification and illumination of the dental operating microscope (Global Surgical Corporation St. Louis, MO, USA) ×8, using an Endo-Access bur (Dentsply Maillefer, USA). Then, a no. 10 k-file (Kerr USA) was introduced to check the patency of the canal. At around 16 mm length insertion of instrument, a resistance was felt. Again, after copious irrigation with 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and application of Glyde (Dentsply Maillefer, USA) a 10 k-file was introduced in a watch winding motion. Again, resistance was felt at around 17 mm length, and resistance was felt even in withdrawing the instrument. Immediately, an intraoral periapical (IOPA) radiograph with the instrument was taken. IOPA revealed that the instrument had hooked itself into the canal because of tunneling of the canal [Figure 2a]. In an attempt to withdraw the instrument, it got separated at the middle-third of the canal [Figure 2b]. Subsequently, it was planned to bypass and or to retrieve the separated instrument.

Figure 2.

(a) The instrument had hooked itself into the canal because of tunneling of the canal. (b) Separated file fragment at the middle third of the canal. (c) Instrument bypassed the separated file fragment. (d) Retrieval of separated file fragment. (e) Biodentine was used to obturate complete root canal system. (f) A 2-year follow-up establishes initiation of periapical healing. (g) A 5-year follow-up establishes significant periapical healing. (h) A photograph after prosthetic rehabilitation

Using copious irrigation with 17% EDTA and Glyde another no. 10 k-file was introduced into the canal. After a few attempts, the instrument did bypass the separated file fragment [Figure 2c]. Following this, working length was determined using apex locator Root ZX mini (J. Morita MFG. Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) which was found to be 22 mm. Canal preparation was carried out using k-files in a circumferential manner. While using a no. 30 k-file, the fractured fragment got engaged in the file and was retrieved. This was confirmed again with a radiograph [Figure 2d].

The canal enlargement was done using a combination of hand k-files and rotary nickel-titanium files (K3-XF, SybronEndo, Glendora, CA, USA). The root canals were copiously irrigated with 5.2% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and 17% EDTA solution during the preparation. Following this, final irrigation was done with 2% chlorhexidine solution (V-concept, Vishal Dentocare, India). Calcium hydroxide (Dento Sure Cal, SatendraPolyfrobs, Nashik [MS] India) was placed as an intracanal medicament, and access cavity was temporized with Cavit-G (3M ESPE, USA). The patient was recalled after 2 weeks. On 2-week recall visit, the tooth was asymptomatic. Root canals were irrigated again with normal saline and 5.2 NaOCl % alternately and dried using absorbent points.

BD capsule (BD; Septodont, Saint-Maurdes Fosses, France) was mixed as per manufacturer's instructions and was placed in the root canal with an mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) carrier (Dentsply Maillefer, USA) and was condensed using hand pluggers (Dentsply Maillefer, USA) to obturate complete root canal system along with the resorptive defect. The vertical condensation pressure extruded the BD material beyond the confines of root canal which was although undesirable, but the patient was asymptomatic during and after the treatment [Figure 2e]. The ICR defect was also restored using BD. The access cavity was sealed using the restoration of light-cured nanohybrid composite-resin Filtek Z250 XT (3M, USA). On a 2-year and 5-year follow-up, respectively, periapical healing was evident [Figure 2f-g]. Prosthetic rehabilitation was done following the successful results [Figure 2h].

DISCUSSION

Resorption can be physiologic or pathologic condition leading to destruction of dentin, cementum, and/or bone. It may be due to insult to pulp and/or periodontal ligament. It can be secondary to trauma, luxation, orthodontic movement, or chronic pulpal and periodontal diseases. Root canal replacement resorption is a variant of internal resorption. It involves dentinal resorption and a subsequent deposition of material that does not resemble dentin but may be similar to bone or cementum. Resorptive defects can be either internal, external, or a combination of both. ITR is a variant of root canal replacement resorption where tunneling resorption occurs next to the root canal. ITR is common in luxation or coronal root fracture injuries.[3,7] However, in the case presented, although there was a history of trauma but no luxation or root fracture was evident.

ITR might consequently get arrested and sometimes complete obliteration of pulp space with bone-like tissue may occur. The origin of metaplastic hard tissues in the canal space has been explained by various hypothesis. The role of postnatal dental pulp stem cells seen in the apical vital part of root canal has been implicated in the production of metaplastic tissues, secondary to resorptive insult. Another hypothesis attributes granulation and metaplastic hard tissues to be of nonpulpal origin and derived from cells belonging to vascular compartments or periodontium. Here, the substitution of pulpal tissues by periodontal tissues, due to internal resorption is emphasized. This is similar to the development of connective tissue in the pulp space, in the presence of blood clot. In this case, tunneling had taken place, and partial obliteration of the canal was evident. This may attribute to a questionable role of cells from vascular compartment or periodontium owing to a reduced vascular supply.[1,3]

ICR is a form of external inflammatory root resorption. This type of resorption has been extensively described by Heithersay[8] It has been classified on the basis of extent of damage to mineralized tissue. The ICR in the present case corresponded to Class 2 type where the lesion is well defined and with a little extension into the pulp chamber. Trauma has been said to be a common etiology for such type of lesions. ICR is mostly identified during radiographic or clinical examination as it generally presents without symptoms.[3]

The clinical presentation of resorption is determined by the location and extent of lesions within the tooth. For a partially vital pulp, there may be symptoms pointing toward pulpitis, but if the resorption is inactive and pulp is necrotic, then the patient may complain of symptoms mimicking apical periodontitis. In such cases, a sinus tract indicating a root perforation or chronic apical abscess might be clinically detected. A history of traumatic injury of the tooth is assumed to be followed by ITR and ICR represented as metaplastic changes in an obliterated pulp chamber and loss of mineralized tissue.[1,3]

CBCT as a diagnostic imaging tool is of great use to clinicians in arriving at a decision regarding the lesion and tooth involved. The data acquired using CBCT offers an enhanced 3D image of the tooth, the lesion, and the surrounding structures. This, in turn, helps in assessing the true nature of the lesion as well as any perforations and treatment outcomes can be precisely determined. In this case, CBCT was extremely valuable in determining the location and extent of ITR and ICR, which otherwise would have been difficult to analyze considering only the RVG or IOPA.[4] The axial sections determined that the canal had an irregular shape with scattered radioopacity indicative of ITR whereas, in other normal teeth, the root canals had a regular outline with a normal radiolucency.

As discussed by various authors, obliteration of the canal due to calcific metamorphosis poses a clinical challenge during root canal treatment which can be due to trauma, prolonged pathology due to caries, aging, periodontal, and orthodontic reasons. Similarly, in the presented case, a concomitant bone-like material deposition following resorption was encountered. A no. 10-k file got separated during its exploration due to tunneling and was later bypassed and retrieved during the preparation. Calcified and tortuous canals due to ITR prove to be a challenge for clinicians and studies have pointed that the number of irretrievable and separated instruments are usually high in completely obliterated canals.[9]

Root canal obturation and restoration of ICR were done using BD, a bioceramic material with biological properties superior to those of the MTA, which is routinely used in the repair of perforations and resorptive defects. MTA is the material of choice owing to its outstanding sealing property and high biocompatibility.[10] The reason behind choosing BD over MTA is its reduced handling time of only 12 min and superior mechanical properties. BD is supplied in liquid and powder compositions. Tricalcium silicate, calcium carbonate, and zirconium oxide are the powder ingredients while the water, calcium chloride, and a modified polycarboxylate are the ingredients of liquid. The powder is kept in a disposable cap, and a single drop of liquid is dropped onto it. The mixing of liquid and powder is done using an amalgamator for 30 s. The mix can be directly applied over the area under operation using a carrier and a plugger as a bulk dentin substrate. The handling and application of BD are thus relatively simple, and it sets quicker in comparison to MTA. Hence, indicating that BD can be an effective and exciting alternative to other existing materials. A follow-up of the reported case after 5 years presented with a successful outcome ensuing obturation and restoration with BD.[5,11] Recently, biomaterials such as NeoMTA PLUS (Avalon Biomed, Bradenton, Florida), MTA Repair HP (Angelus Ltd. Brazil), and EndoSequence Bioceramic Root Repair Material (Brasseler USA) have been introduced which can be used in the treatment of ITR and ICR cases.[12]

CONCLUSION

This case report shows that the use of better imaging tools such as CBCT and superior bioactive materials such as BD can lead to favorable outcomes in clinically difficult and challenging cases of ITR associated with ICR.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Vinod Bhandari, Founder Chairman, and Dr.Manjushree Bhandari, Chairperson, SAIMS for their support toward the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel S, Ricucci D, Durak C, Tay F. Internal root resorption: A review. J Endod. 2010;36:1107–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haapasalo M, Endal U. Internal inflammatory root resorption: The unknown resorption of the tooth. Endod Topics. 2006;14:60–79. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salzano S, Tirone F. Conservative nonsurgical treatment of class 4 invasive cervical resorption: A Case series. J Endod. 2015;41:1907–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel S, Dawood A. The use of cone beam computed tomography in the management of external cervical resorption lesions. Int Endod J. 2007;40:730–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borkar S, de Noronha de Ataide I. Management of a massive resorptive lesion with multiple perforations in a molar: Case report. J Endod. 2015;41:753–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daltoé MO, Paula-Silva FW, Faccioli LH, Gatón-Hernández PM, De Rossi A, Bezerra Silva LA, et al. Expression of mineralization markers during pulp response to biodentine and mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 2016;42:596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X, Thibodeau B, Trope M, Lin LM, Huang GT. Histologic characterization of regenerated tissues in canal space after the revitalization/revascularization procedure of immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2010;36:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heithersay G. Invasive cervical resorption. Endod Topics. 2004;7:73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madarati AA, Watts DC, Qualtrough AJ. Factors contributing to the separation of endodontic files. Br Dent J. 2008;204:241–5. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobovitz M, de Lima RK. Treatment of inflammatory internal root resorption with mineral trioxide aggregate: A case report. Int Endod J. 2008;41:905–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendyk-Szeffer M, Łagocka R, Trusewicz M, Lipski M, Buczkowska-Radlińska J. Perforating internal root resorption repaired with mineral trioxide aggregate caused complete resolution of odontogenic sinus mucositis: A case report. J Endod. 2015;41:274–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomás-Catalá CJ, Collado-González M, García-Bernal D, Oñate-Sánchez RE, Forner L, Llena C, et al. Biocompatibility of new pulp-capping materials NeoMTA plus, MTA repair HP, and biodentine on human dental pulp stem cells. J Endod. 2018;44:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]