Abstract

Background:

Composite resin, serves as esthetic alternative to amalgam and cast restorations. Posterior teeth can be restored using direct or indirect composite restorations. The selection between direct and indirect technique is a clinically challenging decision-making process. Most important influencing factor is the amount of remaining tooth substance.

Aim:

The aim of this systematic review was to compare the clinical performance of direct versus indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth.

Materials and Methods:

The databases searched included PubMed CENTRAL (until July 2015), Medline, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The bibliographies of clinical studies and reviews identified in the electronic search were analyzed to identify studies which were published outside the electronically searched journals. The primary outcome measure was evaluation of the survival of direct and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth.

Results:

This review included thirteen studies in which clinical performance of various types of direct and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth were compared. Out of the thirteen studies which were included seven studies had a high risk of bias and five studies had a moderate risk of bias. One study having a low risk of bias, concluded that there was no significant difference between direct and indirect technique. However, the available evidence revealed inconclusive results.

Conclusion:

Further research should focus on randomized controlled trials with long term follow-up to give concrete evidence on the clinical performce of direct and indirect composite restorations.

Keywords: Clinical evaluation, indirect technique, posterior teeth, single-visit direct composite restorations, survival rate

INTRODUCTION

Increase in demand for esthetics has led to the development of tooth-colored, nonmetallic restorations such as direct composite restorations, indirect composite inlays, and ceramic inlays or onlays.[1]

Ceramic restorations have the disadvantages of being expensive, brittle, prone to fracture and can induce wear with opposing tooth's surface.[2] Recently, there has been increase in the use of resin composites in posterior teeth. Composites typically involve filler particles dispersed within a matrix phase.

Among the currently available composite materials, hybrid, microfilled and nanofilled composites are commonly being used for posterior restorations. Microfilled composites have 37%–40% volume filler loading, whereas nanofilled composites have 60% volume filler loading.[3] Nanofilled composites show high translucency similar to microfilled composites and physical properties similar to hybrid composite.[4] In addition to being esthetic, these materials are relatively less expensive, induce lesser wear of opposing tooth structure and are based on the principle of minimally invasive procedure.

There are different techniques for placement of composite resin restorations. It includes direct and indirect technique. The selection between direct and indirect technique is a challenging decision making process. Single visit direct posterior composite restorations allows for preservation of tooth structure.[5] In this technique, following etching and application of bonding agent to the prepared cavity, composite restoration is built up in increments, curing one layer at a time allowing the practitioner to sculpt the restoration. Hence, cavities are filled incrementally with facially and lingually inclined mesiodistal layers of maximum 2 mm. The layering technique effectively reduces polymerization stress by minimizing the C-factor. As the C-factor reduces, the bond strength increases.

Advantages of direct technique include increased strength of remaining tooth structure and potential for repair. However, mechanical strength of these restorations is inferior to that of indirect composite restorations. Other disadvantages include occlusal and proximal wear, surface roughness, marginal discoloration, loss of marginal integrity, postoperative sensitivity, secondary caries, cusp flexure, technique sensitive, less-than-ideal bonding to dentin, and low fracture toughness.

Indirect technique refers to fabrication of the restoration outside the oral cavity in the laboratory following which it is luted to the tooth with resin cement. There are two types of indirect composite restorations, first and second generation of indirect composite restorations.

The first generation of indirect composite restorations was introduced in the 1980s. These restorations have shown failures in clinical studies. In spite of their secondary curing, they exhibited low levels of flexural strength (60–80 MPa) and elastic modulus (2–3.5 GPa), a resin volume more than 50% and higher wear levels.[6]

The fabrication process differs for direct composite inlays and indirect inlays. For direct composite inlays first a separating medium is applied to the prepared tooth. The resin pattern is then formed, light-cured and removed from the preparation. The rough inlay is then exposed to additional light for approximately 4–6 min or heat activated at 110°C for 7 min, after which the preparation is etched, the inlay is cemented into place with a dual-cure resin, and is then polished. This technique can be completed in a single sitting since it eliminates the need for an impression of the cavity.[7]

Indirect inlay system requires an impression to fabricate the inlay in the laboratory. In addition to conventional light-curing and heat-curing for polymerization, laboratory processing may use heat (140°C), pressure (0.6 MPa for 10 min) and nitrogen atmosphere. These materials have improved physical properties, resistance to wear and attain a higher degree of polymerization. The polymerization shrinkage does not occur in the prepared tooth, so induced stresses are reduced which reduces the potential for leakage.

To overcome the disadvantages of first generation indirect composites, in the early 1990s, a second generation of indirect composites was introduced which included microhybrid composites with fillers of approximately 66% by volume. This resulted in improved mechanical properties with flexural strength in the range of 120–160 MPa and elastic modulus of 8.5–12 GPa.[8]

Composite inlays provide better contouring of proximal surfaces, occlusal contacts, improved wear resistance, reduced polymerization shrinkage, improved fracture resistance, and biocompatibility.[9] The drawbacks of composite inlays are increased cost and time, requires two appointments, fabrication of a temporary restoration, and low potential for repair.

Hence, the selection between direct and indirect composite restorations is challenging. Many clinical studies have been performed on success or survival rate of direct and indirect composite restorations individually. Very few articles have studied comparing direct versus indirect composite restorations. Hence, the primary objective of this systematic review was to compare the clinical performance of direct versus indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth.

Aim

This systematic review aimed at comparing the clinical performance of direct versus indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth.

Structured question

Is there a better clinical performance of direct composite restorations when compared with indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources used

For identification of studies included or considered for this review, detailed search was done in the following databases:

PubMed advanced search (until July 2015)

Medline

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

Language

No language restrictions were applied during the electronic search. Articles with translations of foreign language available were included to eliminate possible language bias.

Hand searching

Journal of Restorative Dentistry.

Types of studies

Studies included were randomized controlled trials and clinical trials comparing direct and indirect composite restorations.

Inclusion criteria

Patients 18–55 years of age with vital posterior teeth.

Exclusion criteria

The studies which were excluded are:

Case reports/case series

Animal studies

In vitro studies

Studies not meeting the inclusion criteria

Studies in which direct and indirect composite restorations have not been compared.

RESULTS

Description of studies

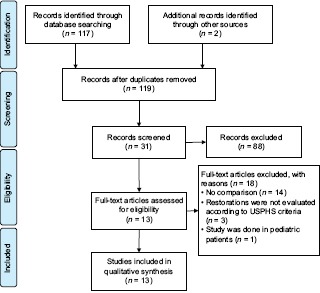

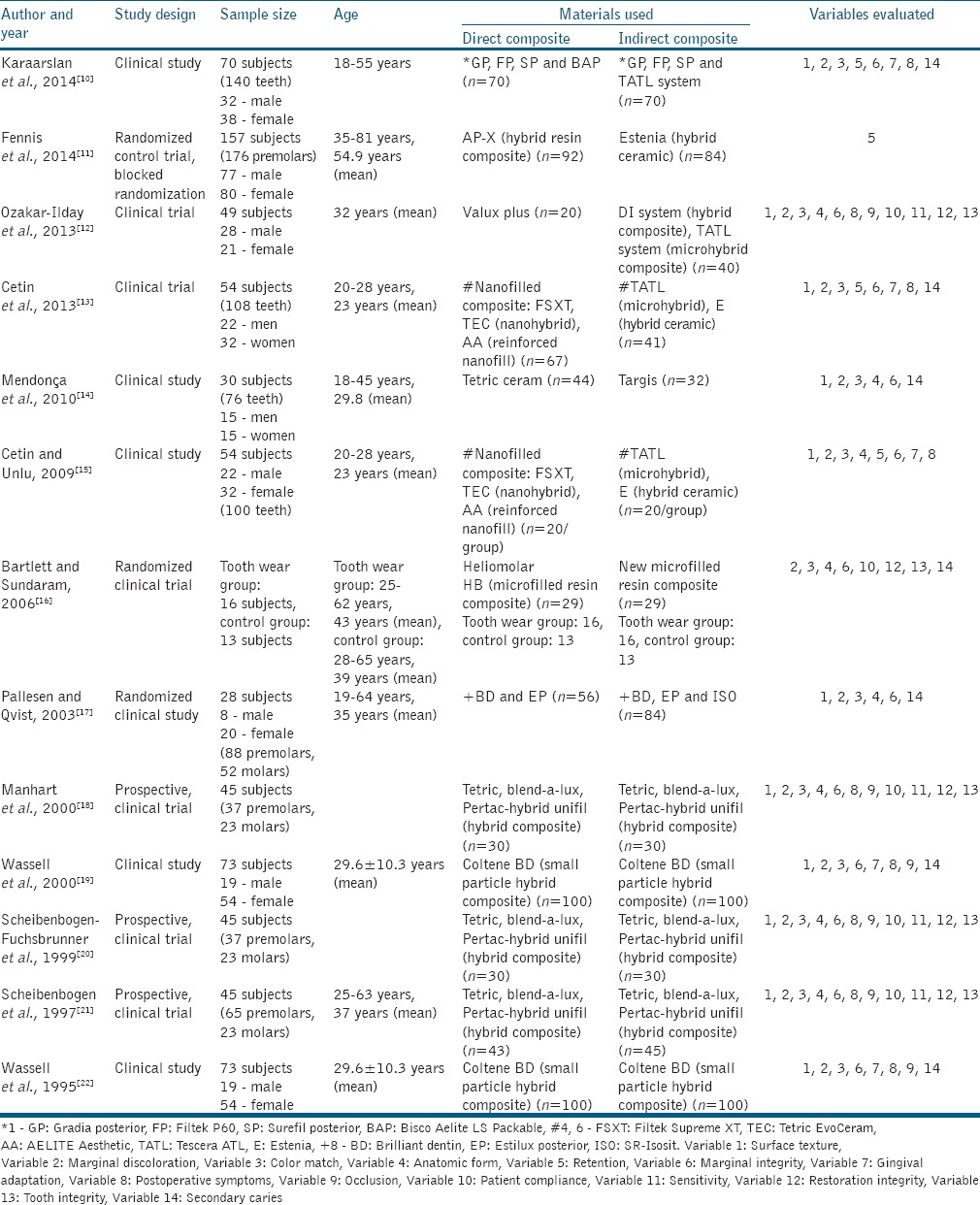

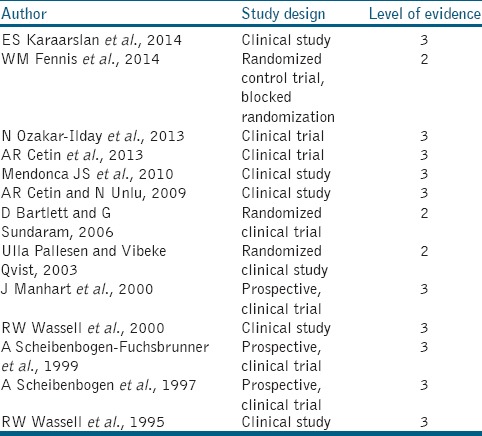

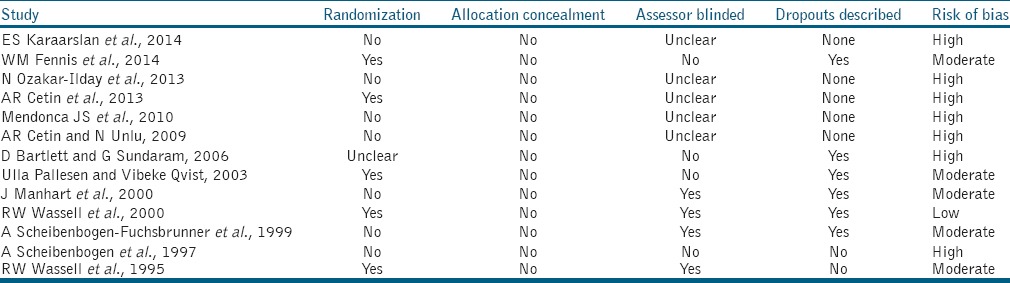

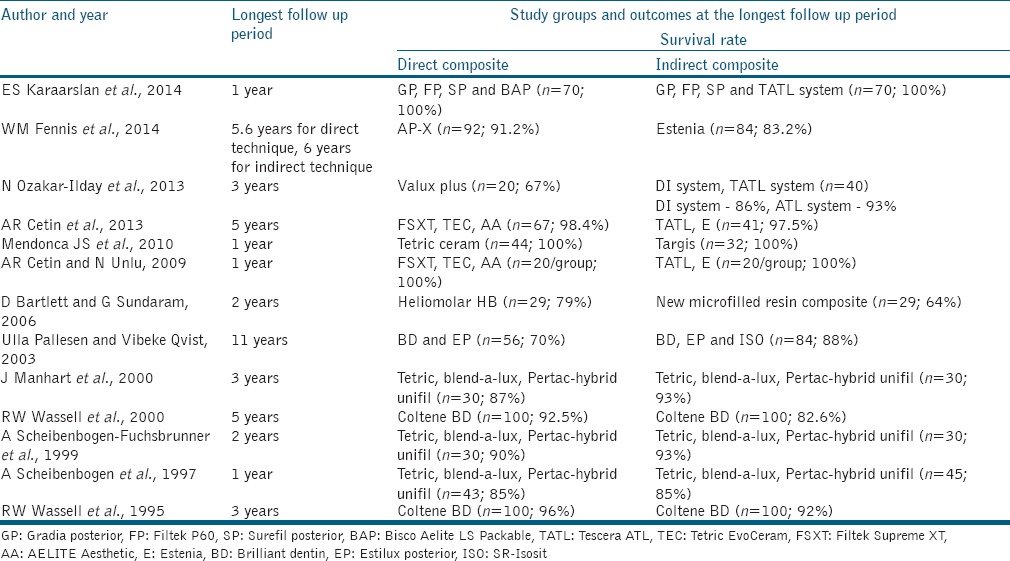

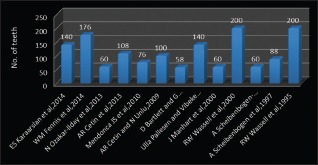

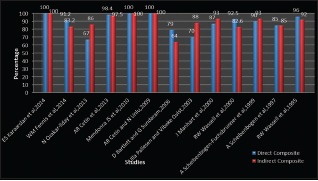

The search identified 117 publications, of which 88 were excluded after reviewing the title or abstract. Full articles were obtained for 29 studies; 18 of these publications were excluded after reading the full text article. Hence, a total of 11 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Two handsearched articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Therefore, a total of 13 publications fulfilled all criteria for inclusion. [Chart 1 shows the search flowchart, general information of selected articles are given in Tables 1 and 2 shows the evidence level of selected articles, Table 3 shows the risk of bias– major criteria and outcome of included studies are given in Table 4]. Graph 1 shows the sample size distribution and Graph 2 shows the survival rate.

Chart 1.

Search flow chart

Table 1.

General information of selected articles

Table 2.

Evidence level of selected articles

Table 3.

Risk of bias-major criteria

Table 4.

Outcome in the included studies summation tables for variables of interest

Graph 1.

Sample size distribution

Graph 2.

Survival rate

DISCUSSION

A total of 1466 teeth were included in this review. Out of 1466 teeth, 741 teeth received direct composite restorations and 725 teeth received indirect composite restorations. Age group of the patients was <55 years.

Of the thirteen studies included in this review, three were randomized controlled clinical trials and remaining 10 were comparative clinical trials. Follow-up period was 6 years, 2 years, 11 years, 5 years, 3 years, 1 year, 1 year, 1 year, 3 years, 5 years, 3 years, 1 year, and 2 years, respectively. All the patients in whom various types of restorations were placed were followed up and variables assessed were as follows: surface texture, marginal discoloration, color match, anatomic form, retention, marginal integrity, gingival adaptation, postoperative symptoms, occlusion, patient compliance, sensitivity, restoration integrity, tooth integrity, and secondary caries.

Owing to the heterogeneity among the studies such as differences in the composite type, sample size and follow-up period, we could not perform a meta-analysis.

Interpretation of results

According to Karaarslans et al.,[10] the study was performed on seventy patients. 140 teeth were equally divided into two groups (n = 70). Seventy patients were in Group-I (direct composite): Gradia Posterior (GP), P60 (Filtek P60 [FP]), Surefil Posterior (SP), and Bisco Aelite LS Packable (BAP) and Group-II (indirect composite): GP, FP, SP and Tescera ATL (TATL) system TESCERA™ ATL™ (Aqua, Thermal, Light) [Table 1]. Variables evaluated were surface texture, marginal discoloration, color match, retention, marginal integrity, gingival adaptation, postoperative symptoms, and secondary caries. This study concluded that indirect restorations have less surface roughness, postoperative sensitivity, and soft-tissue irritation than direct restorations. The clinical performances of the indirect restorations were more satisfactory than the direct restorations.

According to Fennis et al.,[11] 176 premolars in 157 patients were divided into two groups, namely, Group-I (direct composite):AP-X (n = 92) and Group-II (indirect composite): Estenia (n = 82) [Table 1]. In this study, retention variable was evaluated. This study concluded that there was no statistically significant difference between direct and indirect restorations.

According to Ozakar-Ilday et al.,[12] 49 individuals were divided into two groups. Group-I (direct composite): Valux plus (n = 20), Group-II (indirect composite): DI system and TATL system (n = 40). The results of this study concluded that indirect resin restorations showed better scores than direct composite restorations.

According to Cetin et al.,[13] 108 teeth in a group of 54 individuals were included and distributed into two groups. Group-I (direct composite): Filtek Supreme XT (FSXT), Tetric EvoCeram (TEC) and AELITE Aesthetic (AA) (n = 67), Group-II (indirect composite): TATL and E (n = 41) [Table 1]. Variables evaluated in this study were surface texture, marginal discoloration, color match, retention, marginal integrity, gingival adaptation, postoperative symptoms, and secondary caries. This study concluded that there was no statistically significant difference between direct and indirect restorations.

According to Mendonça et al.,[14] 76 teeth in 30 patients were divided into two groups: Group-I (Direct composite): Tetric Ceram (n = 44) and Group-II (indirect composite): Targis (n = 32) [Table 1]. The following variables were evaluated: surface texture, marginal discoloration, color match, anatomic form, marginal integrity, and secondary caries. The results of this study concluded that direct restorations performed better than indirect composite inlays for marginal integrity.

According to Cetin and Unlu,[15] 100 teeth in 54 patients were divided into two groups of 20 restorations per group (n = 20). Group-I (Direct composite): FSXT, TEC, and AA (n = 20/group) and Group-II (Indirect composite): TATL and E (n = 20/group) [Table 1]. Variables evaluated in this study were surface texture, marginal discoloration, color match, anatomic form, retention, marginal integrity, gingival adaptation, and postoperative symptoms. This study concluded that there was no statistically significant difference between direct and indirect restorations.

According to Bartlett and Sundaram,[16] 16 patients were included in tooth wear group and 13 patients in control group. Twenty-nine direct and indirect restorations were placed [Table 1]. The results of this study concluded that the use of direct and indirect composite restorations in worn posterior teeth is contraindicated.

According to Pallesen and Qvist,[17] 140 teeth in 28 individuals were divided into Gr-I (Direct composite): Brilliant Dentin (BD) and Estilux posterior (EP) (n = 56) and Group-II (indirect composite): BD, EP and ISO (n = 84) [Table 1]. This study revealed no difference in the long-term performance of direct restorations or inlays made from the same material.

According to Manhart et al.[18] 60 teeth in 45 patients were distributed equally into Group-I (Direct composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 30) and Group-II (Indirect composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 30) [Table 1]. This study concluded that inlays exhibited better anatomic form of the surface than direct restorations.

According to Wassell et al.,[19] 73 patients received 100 pairs of direct and indirect restorations made from the same material (Coltene BD) [Table 1]. This study concluded that there was no significant difference in the clinical performance between direct and indirect technique and the direct inlay method gave no clinical advantage over conventional, incremental placement technique.

According to Scheibenbogen-Fuchsbrunner et al.,[20] 60 teeth were divided into Group-I (direct composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 30) and Group-II (indirect composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 30) [Table 1]. This study concluded that inlays demonstrated better anatomic form of the surface than direct restorations.

According to Scheibenbogen et al.[21] 88 teeth were divided into Group-I (Direct composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 43) and Group-II (Indirect composite): Tetric, Blend-a-lux, Pertac-Hybrid Unifil (n = 45) [Table 1]. The results of this study concluded that for the criteria surface texture, anatomical form of surface and occlusion, inlays showed superior clinical performance.

According to Wassell et al.[22] 73 patients received 100 pairs of direct and indirect restorations made from the same material (Coltene BD) [Table 1]. This study observed that the clinical performance of both types of materials was similar.

Defending the results

Indirect composite restorations have superior surface texture, anatomic form, occlusion, tooth integrity, lesser sensitivity, gingival bleeding and marginal discoloration whereas direct composite restorations have shown superior restoration integrity. However, the available evidence reveals there was no significant difference in the clinical performance between direct and indirect technique. The direct inlay technique gave no clinical advantage over conventional, incremental placement.

Quality of evidence

Three of the studies included in this review have a level of evidence 2, whereas remaining ten studies have level of evidence 3. Three studies are randomized clinical trials, thus the level of evidence is high [Table 2]. One study had a low risk of bias. Five out of thirteen trials included in this systematic review showed a “moderate” risk of bias, whereas seven studies showed a “high” risk of bias [Table 3].

Report on outliers data

No outlier data obtained.

Inference

Indirect composite inlays showed superior clinical performance to direct composite restorations in spite of greater loss of tooth structure, more clinical steps and procedure of fabrication and exhibited significantly better anatomic form than direct composite restorations. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the clinical performance between direct and indirect technique.

Direct and indirect composite restorations in molars showed significantly higher failure rate compared with premolars. Restoration of worn posterior teeth using direct and indirect composite restorations is contraindicated.

Further studies must be performed with standard study procedures and larger or adequate sample size to give concrete evidence on the long term clinical performance of direct and indirect composite restorations. Furthermore, there is a need for comparison of direct fiber-reinforced composite and indirect composite restorations as no studies have been reported so far.

CONCLUSION

With the available evidence, this review concludes that three studies included in this review have high level of evidence, seven studies have a high risk of bias and five studies have moderate risk of bias. One study having a low risk of bias, concluded that there was no significant difference between direct and indirect technique.

Out of five studies that have a moderate risk of bias, three studies reported that there was no significant difference between direct and indirect composite restorations and remaining studies concluded that indirect inlays demonstrated significantly better anatomic form of surface than direct composite restorations. Among the seven studies with high risk of bias, three studies reported that composite inlays showed superior clinical performance than direct composite restorations, another three studies concluded that there was no significant difference between direct and indirect composite restorations. One study reported that direct composite restorations performed better than indirect composite inlays for marginal integrity. Therefore, properly designed randomized controlled studies with long-term follow-up must be performed to give concrete evidence on the clinical performance of direct and indirect composite restorations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Manhart J, Scheibenbogen-Fuchsbrunner A, Chen HY, Hickel R. A 2-year clinical study of composite and ceramic inlays. Clin Oral Investig. 2000;4:192–8. doi: 10.1007/s007840000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burke EJ, Qualtrough AJ. Aesthetic inlays: Composite or ceramic? Br Dent J. 1994;176:53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu H, Lee YK, Oguri M, Powers JM. Properties of a dental resin composite with a spherical inorganic filler. Oper Dent. 2006;31:734–40. doi: 10.2341/05-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitra SB, Wu D, Holmes BN. An application of nanotechnology in advanced dental materials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1382–90. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ericson D. What is minimally invasive dentistry? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(Suppl 1):287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peutzfeldt A. Indirect resin and ceramic systems. Oper Dent. 2001;200:1153–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garber DA, Goldstein RE. Porcelain and Composite Inlays and Onlays. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co. Inc; 1994. pp. 117–33. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miara P. Aesthetic guidelines for second-generation indirect inlay and onlay composite restorations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1998;10:423–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard NY. Advanced use of an esthetic indirect posterior resin system. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1997;18:1044–61. 1048, 1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaarslan ES, Ertas E, Bulucu B. Clinical evaluation of direct composite restorations and inlays: Results at 12 months. J Res Dent. 2014;2:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fennis WM, Kuijs RH, Roeters FJ, Creugers NH, Kreulen CM. Randomized control trial of composite cuspal restorations: Five-year results. J Dent Res. 2014;93:36–41. doi: 10.1177/0022034513510946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozakar-Ilday N, Zorba YO, Yildiz M, Erdem V, Seven N, Demirbuga S, et al. Three-year clinical performance of two indirect composite inlays compared to direct composite restorations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:e521–8. doi: 10.4317/medoral.18491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cetin AR, Unlu N, Cobanoglu N. A five-year clinical evaluation of direct nanofilled and indirect composite resin restorations in posterior teeth. Oper Dent. 2013;38:E1–11. doi: 10.2341/12-160-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendonça JS, Neto RG, Santiago SL, Lauris JR, Navarro MF, de Carvalho RM, et al. Direct resin composite restorations versus indirect composite inlays: One-year results. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:025–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cetin AR, Unlu N. One-year clinical evaluation of direct nanofilled and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth. Dent Mater J. 2009;28:620–6. doi: 10.4012/dmj.28.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartlett D, Sundaram G. An up to 3-year randomized clinical study comparing indirect and direct resin composites used to restore worn posterior teeth. Int J Prosthodont. 2006;19:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pallesen U, Qvist V. Composite resin fillings and inlays. An 11-year evaluation. Clin Oral Investig. 2003;7:71–9. doi: 10.1007/s00784-003-0201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manhart J, Neuerer P, Scheibenbogen-Fuchsbrunner A, Hickel R. Three-year clinical evaluation of direct and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84:289–96. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2000.108774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wassell RW, Walls AW, McCabe JF. Direct composite inlays versus conventional composite restorations: 5-year follow-up. J Dent. 2000;28:375–82. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(00)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheibenbogen-Fuchsbrunner A, Manhart J, Kremers L, Kunzelmann KH, Hickel R. Two-year clinical evaluation of direct and indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;82:391–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(99)70025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheibenbogen A, Manhart J, Kunzelmann KH, Kremers L, Benz C, Hickel R, et al. One-year clinical evaluation of composite fillings and inlays in posterior teeth. Clin Oral Investig. 1997;1:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s007840050013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wassell RW, Walls AW, McCabe JF. Direct composite inlays versus conventional composite restorations: Three-year clinical results. Br Dent J. 1995;179:343–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]