Abstract

Background:

This article highlights the contribution of collagen structure/stability to the bond strength. We hypothesize that induction of cross-linking in dentin collagen fibrils improves dentin collagen stability and thus bond strength with composite also improves.

Aims:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of collagen cross-linking agents on the shear bond strength of composite resins.

Subjects and Methods:

One hundred human permanent teeth were randomly divided into three groups: Group I (n = 20) – no dentin pretreatment done, Group II – dentin pretreatment with 10% sodium ascorbate for 5 min (IIa) and 10 min (IIb), and Group III – dentin pretreatment with 6.5% proanthocyanidin (PA) for 5 min (IIIa) and 10 min (IIIb). A composite resin was bonded on prepared surfaces and cured. Thermocycling was done, and shear bond strength of the prepared samples was tested using a universal testing machine.

Results:

Values of Group I (control) were lowest whereas that of Group II (sodium ascorbate) were highest. The following order of shear bond strength was observed: IIb > IIa > IIIb ~ IIIa > I. Results for sodium ascorbate were found to be time dependent, whereas for PA, differences were nonsignificant.

Conclusions:

Treatment of dentinal surfaces with collagen cross-linking agent increases the shear bond strengths.

Keywords: Adhesives, bond strength, dentine, enamel, pretreatment

INTRODUCTION

Bonding of composite resin to dentin has always been a challenge for the clinicians. Although there is an improvement in handling and bonding characteristics of the newer dental materials,[1,2] the collagen structure and stability of the dentin bond strength are still a challenge. Studies have proved that collagen in the hybrid layer is affected by enzymatic degradation, leading to bond failure over time.[3,4]

Collagen fibrils in tissue are stabilized by lysyl oxidase-mediated covalent intermolecular cross-linking.[5] The biomechanical properties of type I collagen can be improved by introducing more cross-links within and/or between the fibrils with the treatment of specific chemical agents.

Grape seed extract, which is a naturally occurring cross-linker, mainly composed of proanthocyanidins (PAs), could be a good candidate to fulfill such role. It is a natural plant metabolite and showed to possess low toxicity and ability to induce exogenous cross-links.[6] PA-based compounds can improve dentin collagen physical properties.[7,8] Another such important agent is ascorbic acid. It is an essentially required component in the synthesis of hydroxyproline and hydroxylysine in collagen. Hydroxyproline serves to stabilize the collagen triple helix. Hydroxylysine is necessary for the formation of the intermolecular crosslinks in collagen. It is believed that ascorbate modulates collagen production through its effect on prolyl hydroxylation.[9] Hence, we can employ it as an effective chairside procedure to overcome the disadvantage of reduced bond strength of composite resin to dentin.

The present study was carried out to evaluate if collagen cross-linking agents such as PA and sodium ascorbate can affect the shear bond strength of composite resin bonded to the dentinal surfaces of the teeth.

The null hypothesis was that “there was no difference in shear bond strength of resin composite with dentin with or without treated with collagen cross-linking agent PA and sodium ascorbate.”

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

One hundred freshly extracted human permanent molars were used in this study with the following exclusion/inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Permanent molars with intact crown

All teeth should be free of caries, any visible discoloration, or crack and without any restoration.

Exclusion criteria

Teeth which did not meet our inclusion criteria were excluded from the study.

The roots of the specimens were mounted in self-cure acrylic resin, with occlusal surface parallel to the floor and extending 4 mm above the surface. Dentin surface was prepared with the help of slow-speed sectioning diamond disc under copious water supply and remove complete enamel portion and exposing the dentinal surface, then the surface of dentin was finished with wet 600 grit silicon carbide paper under running water to produce a standardized smear layer. After that, the dentinal surfaces of the specimens were acid etched with 35% phosphoric acid (SwissTec, COLTENE, Switzerland) as per manufacturers' recommendation.

The specimens were randomly divided into three groups based on the surface treatment of dentin as follows:

Group I (n = 20) – No dentin pretreatment was done

-

Group II (n = 40) – 10% sodium ascorbate pretreatment. This group was further divided into two subgroups based on the pretreatment time as follows:

- Subgroup IIa (n = 20) – The etched dentin surface was treated with 10% sodium ascorbate solution for 5 min and rinsed with water, after which they were blot dried leaving a moist dentinal surface for bonding

- Subgroup IIb (n = 20) – The etched dentin surface was treated with 10% sodium ascorbate solution for 10 min and rinsed with water, after which they were blot dried leaving a moist dentinal surface for bonding.

-

Group III (n = 40) – 6.5% PA pretreatment. This group was further subdivided into subgroups based on pretreatment time as follows:

- Subgroup IIIa (n = 20) – The etched dentin surface was treated with 6.5% PA solution for 5 min and rinsed with water, after which they were blot dried leaving a moist dentinal surface for bonding

- Subgroup IIIb (n = 20) – The etched dentin surface was treated with 6.5% PA solution for 10 min and rinsed with water, after which they were blot dried leaving a moist dentinal surface for bonding.

Bonding for composite resin build-up

Before application of bonding agent, a transparent plastic tube (3 mm in diameter and 5 mm height) was placed on the prepared occlusal surface, and the outer diameter was delineated with lead pencil as a reference mark for the application of the bonding agent. Then, plastic tube was removed, and bonding agent (One Coat Bond SL, SwissTec, COLTENE, Switzerland) was applied according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, it was cured with light-emitting diode light (Woodpecker, Guilin Woodpecker Medical Instruments Co., Ltd., China) for 30 s (according to manufacturer's instruction).

Composite resin buildup

Transparent plastic tube was then fixed manually on the prepared surface of each tooth. A microhybrid composite resin (SwisTec, COLTENE, Switzerland) was applied in five 1 mm layers, and each layer was photopolymerized for 40 s, reaching 5 mm in total height, during which the light was moved around the tube to assure curing of the entire composite resin cylinder. The plastic tube was then removed, and excess composite resin was removed using a polishing disc (Sof-Lex™; 3M Espe, St. Paul, MN, USA). The samples were then stored in distilled water at 37°C for 48 h.

Thermocycling and shear bond strength testing

After 48 h, samples were transferred from distilled water to normal water at 37°C for 24 h and then thermocycled for 500 cycles between 5°C and 55°C with a dwell time of 30 s each and transfer time between two baths was 5 and 10 s.

After thermocycling, shear bond strength tests were performed on a universal testing machine (Unitek, 9450 PC, FIE, India) at a cross-head speed of 1 mm/min until the composite cylinder was dislodged from the tooth. Shear bond strength was calculated as the ratio of fracture load and bonding area, expressed in megapascals (MPa). The results were tabulated and subjected to statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Obtained data analyzed and expressed in mean ± standard deviation (SD). Mean was compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey post hoc test P = 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

The results obtained through statistical analysis depicted that dentin pretreatment significantly increases the shear bond strength of the composite resin with dentin; duration of application of pretreatment materials on dentin also plays a significant role [Tables 1-3].

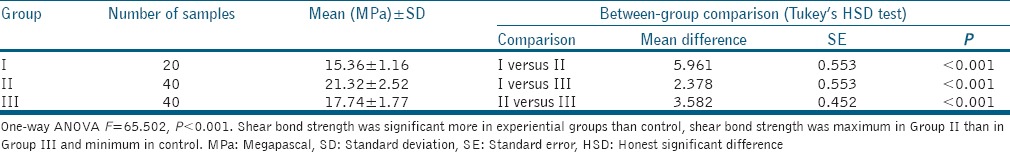

Table 1.

Shear bond strength in different groups irrespective of time of treatment

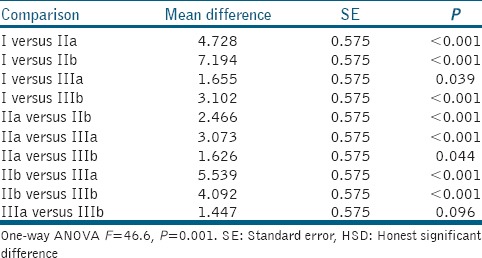

Table 3.

Shear bond strength comparison between group/subgroup (Tukey's HSD test)

Mean difference was found to be maximum between Groups I and IIb and minimum between Groups IIIa and IIIb. All the between-group comparisons except between Groups IIIa and IIIb were significant statistically [Table 3]. On the basis of above evaluation, the following order of shear bond strength was observed in different groups/subgroups:

IIb > IIa > IIIb ~ IIIa > I” with “IIb > IIa > IIIb > IIIa > I”.

It was observed that shear bond strength values in Group I was of lower order, whereas shear bond strength values in Group II were of higher order. Shear bond strength values in Group III were of middle order.

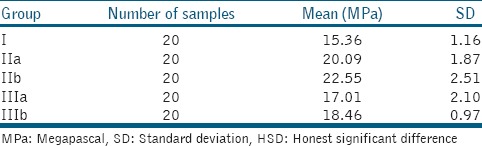

In Group I, shear bond strength ranged from 13.14 to 17.00 MPa with a mean value of 15.36 and a SD of 1.16 MPa. In Group IIa, shear bond strength ranged from 16.31 to 23.07 MPa with a mean value of 20.09 and a SD of 1.87 MPa. In Group IIb, shear bond strength ranged from 18.74 to 29.99 MPa, with a mean value of 22.55 and a SD of 2.51 MPa. In Group IIIa, shear bond strength ranged from 12.36 to 20.26 MPa, with a mean value of 17.01 and a SD of 2.10 MPa. In Group IIIb, shear bond strength ranged from 17.11 to 20.66 MPa, with a mean value of 18.46 and a SD of 0.97 MPa [Table 2].

Table 2.

Shear bond strength in different groups taking time of treatment into consideration

DISCUSSION

The results obtained through statistical analysis depicted that sodium ascorbate and PA application before bonding significantly improve the bond strength of composite with dentin [Table 1]. The increase in bond strength in the present study may be attributed to improve dentin collagen stability, due to the higher number of collagen cross-links.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are such class of enzymes that are known to degrade collagen. These proteins are found in the dentin but more abundant on enamel–dentin junction and in the predentin.[10] The MMPs converted from Pro-MMP which are trapped or bound in the dentin during its formation by lowering the pH to 4.5 or below.[11,12]

Application of self-etching adhesives (acidic resins) to dentin increases 14-fold in MMP enzyme activity.[13]

Thus, adjunctive collagen pretreatment strategies have been proposed to improve dentin adhesion, through the use of agents that maintain the stability of collagen toward enzymatic degradation.[14] These agents include the use of substances that are considered to be inhibitors of MMPs and cysteine cathepsins. Thus, pretreatment with collagen cross-linking agents can promise improvement in the bonding mechanism preserving the integrity of collagen hybrid layer.

Various natural as well as synthetic cross-linking agents such as glutaraldehyde, tannic acid, PA, genipin, and cocoa seed extract have been used to strengthen the hybrid layer and have shown positive results in improving the bond strength to significant levels.[15,16,17]

Results of this study show that sodium ascorbate application significantly improves bond strength compared with control and PA application [Table 3].

In Group IIa (10% sodium ascorbate for 5 min), shear bond strength ranged from 16.31 to 23.07 MPa, with a mean value of 20.09 Mpa and a SD of 1.87 MPa.

In Group IIb (10% sodium ascorbate for 10 min), shear bond strength ranged from 18.74 to 29.99 MPa, with a mean value of 22.55 MPa and a SD of 2.51 MPa.

These results for the sodium ascorbate in the present study were found to be time dependent (P < 0.001), whereas for PA difference was found to be insignificant (P = 0.096) [Table 1 and 2].

The major action of the sodium ascorbate is in the stabilization of the collagen, as a cofactor of hydroxylation of proline and lysine.[18] A study based on energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis has shown that calcium ion concentration after demineralization dropped from the 28.62 to 12.77% and increased to 15.99% after sodium ascorbate treatment for 10 min, With this may due to chemical interaction of sodium ascorbate with collagen fibres in dentine.[19] However, shear bond strength of composite to deep dentin after treatment with 6.5% PA and 10% sodium ascorbate found the statistically significant better results with PA than the sodium ascorbate.[20]

PAs, which form a complex subgroup of the flavonoid compounds, have been found in a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, flowers, nuts, seeds, and bark. PA from grape seed extract has been shown to safely and effectively cross-link collagen in both in vitro and in vivo models and also inhibit MMP activity.[21,22] Considering its wide spectrum of benefits and high biocompatibility, we have selected this agent for this study.

Studies done by Han et al. (2003) and Bedran-Russo et al. and found the improvement in ultimate tensile strength and shear bond strength, respectively, after pretreatment with PA.[7,8] These findings also corroborate with the results of these studies. A statistically significant improvement was seen after pretreatment with PA (P < 0.001) [Table 1].

The proposed mechanisms for interaction between PA and proteins include covalent, ionic, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions.[7,23]

In the present study, molars were selected since they are most commonly restored, due to high incidence of caries.

Therefore, validation and extension of our results await further investigations. The results of the ex vivo assays may not be directly comparable with the in vivo conditions, where all other parameters are to be considered. In vivo research is must to assess the clinical outcome and analysis of these agents so as to make out most of the benefits to the clinical adhesive dentistry.

CONCLUSIONS

We can conclude that the treatment of dentinal surfaces with collagen cross-linking agent increases the shear bond strengths. Results for sodium ascorbate were found to be time dependent, whereas for PA, differences were nonsignificant.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dos Santos PA, Garcia PP, Palma-Dibb RG. Shear bond strength of adhesive systems to enamel and dentin.Thermocycling influence. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2005;16:727–32. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-2609-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Ruggeri A, Cadenaro M, Di Lenarda R, De Stefano Dorigo E, et al. Dental adhesion review: Aging and stability of the bonded interface. Dent Mater. 2008;24:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshiro K, Inoue S, Sano H, De Munck J, Van Meerbeek B. In vivo degradation of resin-dentin bonds produced by a self-etch and an etch-and-rinse adhesive. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:341–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong SR, Vargas MA, Chung I, Pashley DH, Campbell JA, Laffoon JE, et al. Resin-dentin interfacial ultrastructure and microtensile dentin bond strength after five-year water storage. Oper Dent. 2004;29:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamauchi M, Shiiba M. Kannicht C, editor. Lysine Hydroxylation and Crosslinking of Collagen Posttranslational Modifications of Proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology™. Humana Press 2002. 2002;194:277–90. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-181-7:277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han B, Jaurequi J, Tang BW, Nimni ME. Proanthocyanidin: A natural crosslinking reagent for stabilizing collagen matrices. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65:118–24. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedran-Russo AK, Pereira PN, Duarte WR, Drummond JL, Yamauchi M. Application of crosslinkers to dentin collagen enhances the ultimate tensile strength. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2007;80:268–72. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bedran-Russo AK, Pashley DH, Agee K, Drummond JL, Miescke KJ. Changes in stiffness of demineralized dentin following application of collagen crosslinkers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;86:330–4. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murad S, Grove D, Lindberg KA, Reynolds G, Sivarajah A, Pinnell SR, et al. Regulation of collagen synthesis by ascorbic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:2879–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boushell LW, Kaku M, Mochida Y, Bagnell R, Yamauchi M. Immunohistochemical localization of matrixmetalloproteinase-2 in human coronal dentin. Arch Oral Biol. 2008;53:109–16. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaussain-Miller C, Fioretti F, Goldberg M, Menashi S. The role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in human caries. J Dent Res. 2006;85:22–32. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzoni A, Mannello F, Tay FR, Tonti GA, Papa S, Mazzotti G, et al. Zymographic analysis and characterization of MMP-2 and -9 forms in human sound dentin. J Dent Res. 2007;86:436–40. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tay FR, Pashley DH, Loushine RJ, Weller RN, Monticelli F, Osorio R, et al. Self-etching adhesives increase collagenolytic activity in radicular dentin. J Endod. 2006;32:862–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzoni A, Pashley DH, Nishitani Y, Breschi L, Mannello F, Tjäderhane L, et al. Reactivation of inactivated endogenous proteolytic activities in phosphoric acid-etched dentine by etch-and-rinse adhesives. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bedran-Russo AK, Yoo KJ, Ema KC, Pashley DH. Mechanical properties of tannic-acid-treated dentin matrix. J Dent Res. 2009;88:807–11. doi: 10.1177/0022034509342556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellan CS, Pereira PN, Viana G, Chen SN, Pauli GF, Bedran-Russo AK, et al. Solubility study of phytochemical cross-linking agents on dentin stiffness. J Dent. 2010;38:431–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charulatha V, Rajaram A. Influence of different crosslinking treatments on the physical properties of collagen membranes. Biomaterials. 2003;24:759–67. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwarz RI, Bissell MJ. Dependence of the differentiated state on the cellular environment: Modulation of collagen synthesis in tendon cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:4453–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbosa de Souza F, Silva CH, Guenka Palma Dibb R, Sincler Delfino C, Carneiro de Souza Beatrice L. Bonding performance of different adhesive systems to deproteinized dentin: Microtensile bond strength and scanning electron microscopy. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005:158–67. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivasulu S, Vidhya S, Sujatha M, Mahalaxmi S. Shear bond strength of composite to deep dentin after treatment with two different collagen cross-linking agents at varying time intervals. Oper Dent. 2012;37:485–91. doi: 10.2341/11-232-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.La VD, Howell AB, Grenier D. Cranberry proanthocyanidins inhibit MMP production and activity. J Dent Res. 2009;88:627–32. doi: 10.1177/0022034509339487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green B, Yao X, Ganguly A, Xu C, Dusevich V, Walker MP, et al. Grape seed proanthocyanidins increase collagen biodegradation resistance in the dentin/adhesive interface when included in an adhesive. J Dent. 2010;38:908–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ku CS, Sathishkumar M, Mun SP. Binding affinity of proanthocyanidin from waste Pinus radiata bark onto proline-rich bovine achilles tendon collagen type I. Chemosphere. 2007;67:1618–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]