Summary

In a randomized, controlled trial among human immunodeficiency virus–infected pregnant women in an area of Uganda where indoor-residual spraying of insecticide had be recently implemented, adding monthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine to daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole did not reduce the risk of malaria or improve birth outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, malaria, pregnancy, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Abstract

Background.

Daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) and insecticide-treated nets remain the main interventions for prevention of malaria in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected pregnant women in Africa. However, antifolate and pyrethroid resistance threaten the effectiveness of these interventions, and new ones are needed.

Methods.

We conducted a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial comparing daily TMP-SMX plus monthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP) to daily TMP-SMX alone in HIV-infected pregnant women in an area of Uganda where indoor residual spraying of insecticide had recently been implemented. Participants were enrolled between gestation weeks 12 and 28 and given an insecticide-treated net. The primary outcome was detection of active or past placental malarial infection by histopathologic analysis. Secondary outcomes included incidence of malaria, parasite prevalence, and adverse birth outcomes.

Result.

All 200 women enrolled were followed through delivery, and the primary outcome was assessed in 194. There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of histopathologically detected placental malarial infection between the daily TMP-SMX plus DP arm and the daily TMP-SMX alone arm (6.1% vs. 3.1%; relative risk, 1.96; 95% confidence interval, .50–7.61; P = .50). Similarly, there were no differences in secondary outcomes.

Conclusions.

Among HIV-infected pregnant women in the setting of indoor residual spraying of insecticide, adding monthly DP to daily TMP-SMX did not reduce the risk of placental or maternal malaria or improve birth outcomes.

Clinical Trials Registration.

(See the editorial commentary by ter Kuile and Taylor on pages 4–6.)

Malaria in pregnancy is associated with adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, such as spontaneous abortions, stillbirth, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, low birth weight, maternal anemia, and neonatal death [1]. Prior to the widespread implementation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected pregnant women were shown to have an increased risk of parasitemia, clinical malaria, and placental malarial infection, compared with HIV-uninfected pregnant women [2]. In addition, HIV and placental malaria parasite coinfection is associated with an increased risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery, compared with women with either infection alone [2]. The additional risk of placental malarial infection conferred by HIV coinfection is more pronounced with higher parity, a phenomenon supported by laboratory studies indicating that HIV impairs parity-specific immunity [3, 4]. Current strategies for the prevention of malaria during pregnancy in HIV-uninfected women include the use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and intermittent preventive treatment (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP). For HIV-infected pregnant women taking daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) prophylaxis as part of routine care, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends avoiding the use of IPTp with SP, owing to the risk of adverse drug reactions [5]. However, the spread of resistance to the pyrethroid class of insecticides used in ITNs and the antifolate class of drugs used for chemoprevention suggest the need for novel strategies for the prevention of malaria among HIV-infected pregnant women [6, 7].

Artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) have been shown to be effective for the treatment of malaria in pregnancy [8, 9]; however, there are limited data on the use of ACTs for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy and no published studies among HIV-infected women. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DP) is an especially attractive ACT because of its prolonged posttreatment prophylactic effect [10]. Recent data from Kenya and Uganda showed that IPTp with DP was associated with a lower burden of malaria as compared to IPTp with SP among HIV-uninfected pregnant women [11, 12].

We compared the efficacy and safety of daily TMP-SMX versus daily TMP-SMX plus IPTp with monthly DP to prevent placental malarial infection among HIV-infected women living in an area in Uganda with historically high rates of malaria transmission and antifolate resistance. Additional outcomes of interest included other measures of placental malarial infection, adverse birth outcomes, incidence of malaria, and parasite prevalence.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in Tororo, Uganda, an area of historically high malaria transmission intensity with an estimated entomological inoculation rate of 310 infectious bites per person-year in 2012 [13]. Notably, in December 2014, when study enrollment began, a national program of indoor residual spraying of insecticide (IRS) was implemented throughout the district, resulting in a dramatic decrease in the incidence of malaria [14]. Women were recruited from the Tororo District Hospital antenatal clinic, the AIDS Support Organization, and other health centers in the district. Eligible women were ≥16 years of age; infected with HIV-1, as confirmed by 2 assays; lived within 30 km of the study site; and had a pregnancy between 12 and 28 weeks of gestation, confirmed by ultrasonography. Women were excluded if they had a history of any adverse events associated with TMP-SMX or DP therapy, had an active medical problem requiring inpatient evaluation or WHO HIV disease stage 4 conditions that were not stable under treatment, had a history of cardiac problems, had signs of labor, or were taking ritonavir, drugs associated with known risk of torsades de pointes, or cytochrome P450 3A inhibitor medications.

Study participants provided written informed consent in their preferred language. The study protocol was approved by the Makerere University School of Biomedical Sciences Research and Ethics Committee, the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology, and the University of California–San Francisco Committee on Human Research.

Study Design and Randomization

This was a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 200 HIV-infected pregnant women. Women were randomly assigned to receive standard chemoprevention with daily TMP-SMX plus monthly placebo or daily TMP-SMX plus monthly DP in a 1:1 ratio, using permuted variable-sized blocks of 4 and 6. Pharmacists not otherwise involved in the study were responsible for treatment allocation and the preparation of study drugs. All women received daily TMP-SMX prophylaxis (160 mg/800 mg). Each dose of DP (tablets of 40 mg of dihydroartemisinin and 320 mg of piperaquine [Duo-Cotexin, Holley-Cotec]) consisted of 3 tablets given once daily for 3 consecutive days. Participants randomly assigned to receive daily TMP-SMX alone were given DP placebo with the same appearance and number of tablets as active DP. DP or DP placebos were administered every 4 weeks between 16 and 40 weeks of gestational age. Administration of the first daily doses of DP or DP placebo was directly observed in the clinic. The second and third daily doses were taken at home.

Study Procedures

At enrollment, women received a long-lasting ITN, underwent a standardized examination, and had blood samples collected. Women received all of their medical care at a study clinic that was open every day. All participants received combination ART with efavirenz (EFV)/tenofovir/lamivudine and routine HIV care according to Uganda Ministry of Health guidelines, with the addition of HIV-1 RNA monitoring. Routine visits were conducted every 4 weeks, including blotting of and drying blood specimens on filter paper for future molecular testing; routine laboratory testing (complete blood count and measurement of alanine aminotransferase levels) was performed every 8 weeks. Women were encouraged to come to the clinic any time they were ill. Those who presented with a documented fever (defined as a tympanic temperature of ≥38.0°C) or a history of fever in the previous 24 hours had blood specimens collected for a thick blood smear. If the smear was positive for malaria parasites, the patient received a diagnosis of malaria and was treated with artemether-lumefantrine. Participants who required a switch to a protease inhibitor–based regimen owing to virologic failure stopped receiving DP or DP placebo because of potential drug interactions but had malaria and birth outcomes assessed.

Women were encouraged to deliver at the hospital adjacent to the study clinic. Women delivering at home were visited by study staff at the time of delivery or as soon as possible afterward. At delivery, a standardized assessment was completed, including evaluation of the neonate for congenital anomalies, measurement of birth weight, and collection of biological specimens, including placental tissue, placental blood, cord blood, and maternal blood. Following delivery, women were evaluated at postpartum weeks 1 and 6. Adverse events were assessed and graded according to standardized criteria at every visit to the study clinic [15]. Electrocardiography was performed to assess QT intervals corrected using Fridericia’s and Bazett’s formulas in a subset of 55 women just prior to their first daily dose of study drugs and 3–4 hours after their third daily dose of study drugs when they reached 28 weeks gestational age.

Laboratory Procedures

Blood smears were collected in febrile women during pregnancy and from placental, cord and maternal blood at delivery. Blood smears were stained with 2% Giemsa and read by experienced laboratory technologists. A blood smear was considered negative when the examination of 100 high power fields did not reveal asexual parasites. For quality control, all slides were read by a second microscopist and a third reviewer would settle any discrepant readings. Blood specimens for dried blood spot testing were collected at enrollment and every 4 weeks during pregnancy; specimens from placental, cord, and maternal blood were collected at delivery. Dried blood spots were tested for the presence of malaria parasites, using a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) kit as previously described (Eiken Chemical, Japan) [16]. Placental tissues were processed for histological evidence of placental malarial infection as previously described [17]. Slides prepared for histopathologic analysis were read in duplicate, using a standardized case record form, by 2 independent readers (J. A. and G. R.), and any discrepant results were resolved by a third reader (A. M.). Readers were blinded to both treatment assignment and findings of prior reads.

Study End Points

The primary outcome was the prevalence of placental malarial infection, based on the presence of any parasites or malaria pigment detected by histopathologic analysis. Placental histopathologic findings were also classified according to a standardized categorical system [18]. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of symptomatic malaria, the prevalence of parasitemia, based on LAM, and the prevalence of anemia (defined as a hemoglobin level of <11 g/dL) during pregnancy following the administration of the first dose of study drugs; the prevalence of parasitemia at delivery, based on microscopy and LAMP analysis of placental, cord, and maternal blood specimens; and adverse birth outcomes, including spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, low birth weight (defined as a birth weight of <2500 g), preterm delivery (defined as delivery before gestation week 37), congenital anomaly, and a composite of any of these. For women giving birth to twins, delivery outcomes were based on whether the outcome was present in either the child or the placenta. Measures of safety and tolerability included the prevalence of vomiting following administration of study drugs and the incidence of adverse events following the initiation of study drug treatment through postpartum week 6.

Statistical Analysis

To test the hypothesis that the use of TMP-SMX plus monthly DP would be associated with a lower risk of histopathologically detected placental malarial infection as compared to TMP-SMX alone, we assumed a prevalence of placental malarial infection of 20% in the daily TMP-SMX arm, based on prior data [17], and calculated a sample size of 200 to show a 62% reduction with a 2-sided significance level of 0.05 and a power of 80%. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All analyses were done using a modified intention-to-treat approach including all women allocated to treatment with evaluable outcomes of interest. Comparisons of baseline characteristics were made using the t test, for continuous variables, and the χ2 test, for categorical variables. Comparisons of binomial outcomes were made using the χ2 or Fisher exact tests. Comparisons of binomial outcomes, using multivariate analysis to control for potential confounders, were made using log-binomial regression. Comparisons of binomial outcomes with repeated measures were made using generalized estimating equations with a log-binomial family and robust standard errors. Comparisons of incidence measures were made using a negative binomial regression model. Comparison of mean differences in corrected QT intervals was made using a 2-sample t test. All P values were 2 sided, and values of <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Participants and Follow-up

From December 2014 through October 2015, 237 women were screened, of whom 200 were enrolled and underwent random assignment; 100 women were assigned to receive daily TMP-SMX plus monthly placebo, and 100 women were assigned to receive daily TMP-SMX plus monthly DP (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 treatment arms, with the exception of a trend toward a higher proportion of primigravidae enrolled in the TMP-SMX plus monthly DP arm (13% vs 5%; P = .05; Table 1). At enrollment, the mean age was 30 years, the pregnancy in 55% of women was at gestation week ≤20, 57% reported owning an ITN, 91% were receiving TMP-SMX prophylaxis, and 9% had malaria parasites detected by LAMP. At enrollment, 81% of participants were receiving ART, and 68% had received ART for at least 90 days before enrollment. All 200 women enrolled were followed through delivery, and 194 (97%) had placental tissue collected for histopathologic analysis (Figure 1). Two women gave birth to twins with monochorionic placentas.

Figure 1.

Trial profile. Abbreviations: DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Treatment Arm | |

|---|---|---|

| Daily TMP-SMX (n = 100) | Daily TMP-SMX + Monthly DP (n = 100) | |

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 30.3 ± 5.8 | 29.8 ± 6.8 |

| Gestational age | ||

| Overall, wk, mean ± SD | 19.2 ± 4.1 | 19.9 ± 4.5 |

| 12–16 wk | 28 (28) | 25 (25) |

| >16–20 wk | 30 (30) | 26 (26) |

| >20–24 wk | 29 (29) | 27 (27) |

| >24–28 wk | 13 (13) | 22 (22) |

| Gravidity | ||

| 1 pregnancy | 5 (5) | 13 (13) |

| 2 pregnancy | 13 (13) | 12 (12) |

| ≥3 pregnancies | 82 (82) | 75 (75) |

| ITN ownership | 57 (57) | 57 (57) |

| Household wealth index | ||

| Lowest tertile | 33 (33) | 34 (34) |

| Middle tertile | 30 (30) | 36 (36) |

| Highest tertile | 37 (37) | 30 (30) |

| Receiving TMP-SMX prophylaxis | 90 (90) | 91 (91) |

| Receiving ART | 82 (82) | 79 (79) |

| CD4+ T-cell count, cells/ mm3, median (IQR)a | 500 (392–622) | 516 (368–660) |

| HIV load below limit of detection | 51 (51) | 60 (60) |

| WHO HIV disease stage | ||

| 1 | 93 (93) | 97 (97) |

| 2 | 4 (4) | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Detection of malaria parasites by LAMP | 11 (11) | 6 (6) |

Data are no. (%) of study participants, unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; ITN, insecticide-treated net; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; WHO, World Health Organization.

aData are missing for 8 study participants.

Efficacy Outcomes

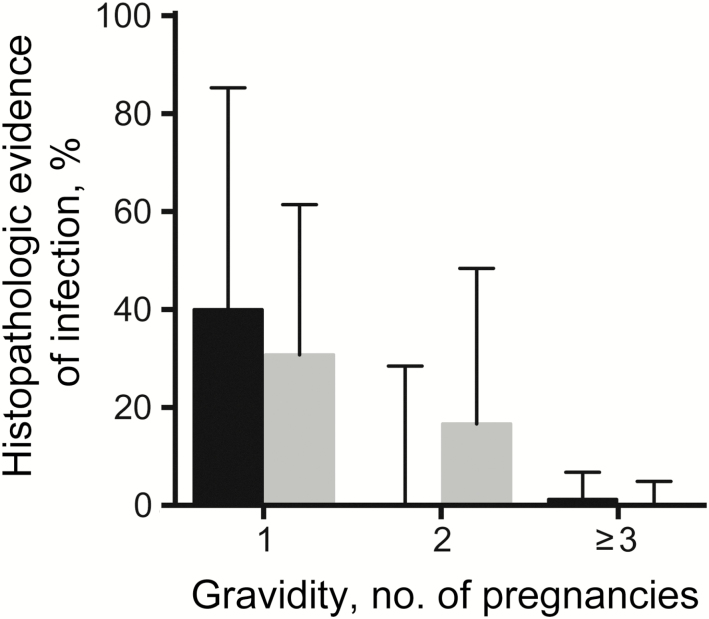

At delivery, the prevalence of histopathologic detection of any placental malarial infection was higher in the TMP-SMX plus monthly DP arm (6.1%), compared with the placebo arm (3.1%), but the difference was not statistically significant (relative risk [RR], 1.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], .50–7.61; P = .50; Table 2). When controlling for gravidity, the risks were nearly identical (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, .29–3.60; P = .97). All 9 placentas positive for placental malarial infection had pigment in fibrin indicative of past infection, but only 2 had parasites indicative of concomitant active infection (1 in each treatment arm). The risk of placental malarial infection, stratified by gravidity and treatment arm, are presented in Figure 2. Independent of treatment arm, the prevalence of histopathologically detected placental malarial infection was significantly lower in multigravidae (0.7%), compared with secundigravidae (8.7%; P = .03) and primigravidae (33.3%; P < .001). Detection of malaria parasites by microscopy or LAMP in placental and maternal blood was uncommon, with no significant differences between the treatment arms (Table 2). No parasites were detected in cord blood. A total of 47 adverse birth outcomes occurred in 35 women. Low birth weight was the most common adverse birth outcome (n = 22), followed by preterm delivery (n = 16), congenital anomaly (n = 5), spontaneous abortion (n = 3), and stillbirth (n = 1). There were no significant differences between the 2 treatment arms for individual adverse birth outcomes and a composite adverse birth outcome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes Assessed at the Time of Delivery

| Outcomes | Treatment Arm, Prevalence, Proportion (%) | RR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily TMP-SMX a | Daily TMP-SMX + Monthly DP | |||

| Malarial infection positivity, by test | ||||

| Histopathologic analysis | 3/96 (3.1) | 6/98 (6.1) | 1.96 (.50–7.61) | .50 |

| Microscopy of placental blood | 0/95 (0) | 1/98 (1.0) | NA | 1.0 |

| LAMP analysis of placental blood | 1/96 (1.0) | 3/98 (3.1) | 2.94 (.31–27.8) | .62 |

| Microscopy of maternal blood | 0/98 (0) | 1/99 (1.0) | NA | 1.0 |

| LAMP analysis of maternal blood | 2/98 (2.0) | 4/100 (4.0) | 1.96 (.37–10.5) | .68 |

| Microscopy of cord blood | 0/94 (0) | 0/97 (0) | NA | NA |

| LAMP analysis of cord blood | 0/94 (0) | 0/96 (0) | NA | NA |

| Birth outcome | ||||

| Spontaneous abortion | 1/100 (1.0) | 2/100 (2.0) | 2.00 (.18–21.7) | 1.0 |

| Stillbirthb | 0/99 (0) | 1/98 (1.0) | NA | .50 |

| Low birth weightb | 11/99 (11.1) | 11/98 (11.2) | 1.01 (.46–2.22) | .98 |

| Preterm deliveryb | 6/99 (6.1) | 10/98 (10.2) | 1.68 (.64–4.54) | .29 |

| Congenital anomalyb,c | 1/98 (1.0) | 4/97 (4.1) | 4.04 (.46–35.5) | .21 |

| Composite birth outcome | 15/100 (15.0) | 20/100 (20.0) | 1.33 (.72–2.45) | .35 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; NA, not applicable; RR, relative risk; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aReference group.

bData are limited to those with a gestational age of ≥28 weeks.

cPolydactyly (n = 2), cleft palate, eye ptosis, and umbilical hernia.

Figure 2.

Risk of any placental malarial infection detection by histopathologic analysis among study participants, stratified by gravidity. Black bars denote the arm that received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) daily. Gray bars denote the arm that received TMP-SMX daily and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine monthly. Error bars indicate upper limits of 95% confidence intervals.

Following the initiation of treatment with study drugs, there was only 1 episode of symptomatic malaria, which occurred in the TMP-SMX arm (Table 3). The parasite prevalence was higher in the TMP-SMX arm (3.1%) as compared to the TMP-SMX plus monthly DP arm (1.4%), but the difference was not statistically significant (RR, 0.45; 95% CI, .13–1.48; P = .19). Maternal anemia was similar between the TMP-SMX (31.6%) and TMP-SMX plus monthly DP (26.7%) arms (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, .61–1.35; P = .62; Table 3).

Table 3.

Longitudinal Outcomes Assessed During Pregnancy

|

Outcome

|

Treatment Arm | Value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily TMP-SMX a | Daily TMP-SMX + Monthly DP | |||

| Incidence measureb | Events, No. (Incidence c) | IRR (95% CI) | ||

| Symptomatic malaria | 1 (0.03) | 0 (0) | NA | .99 |

| Prevalence measured |

Prevalence, Proportion (%) |

RR (95% CI) | ||

| Detection of malaria parasites by LAMP | 12/392 (3.1) | 5/368 (1.4) | 0.45 (.13–1.48) | .19 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin level, <11 g/dL) | 65/206 (31.6) | 51/191 (26.7) | 0.90 (.61–1.35) | .62 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; IRR, incidence rate ratio; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; NA, not applicable; RR, relative risk; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aReference group.

bFollowing administration of the first dose of study drugs.

cNumber per person-year at risk.

dRepeated measures assessed at the time of routine visits following administration of the first dose of study drugs.

Tolerability and Safety Outcomes

Vomiting occurred in <0.2% of women after administration of study drugs, with no differences between study arms (Table 4). There were no significant differences in the incidence of adverse events of any severity or grade 3–4 adverse events. There were 26 grade 3–4 adverse events and 10 serious adverse events, none of which were thought to be related to study drugs (Table 4). No clinical adverse events consistent with cardiotoxicity occurred during the course of the study. Among 55 women (27 in the TMP-SMX arm and 28 in the TMP-SMX plus monthly DP arm) who underwent electrocardiography at gestational week 28, all predosing and postdosing corrected QT intervals were within normal limits (≤450 msec). The mean change in corrected QT intervals was greater in the TMP-SMX plus monthly DP arm, compared with the TMP-SMX arm (15 msec vs 0 msec [P = .02] by use of Fridericia’s formula and 16 msec vs 3 msec [P = .02] by use of Bazett’s formula).

Table 4.

Measures of Tolerability and Safety

| Outcome | Treatment Arm | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily TMP-SMX | Daily TMP-SMX + Monthly DP | ||

| Prevalence measure | Prevalence, Proportion (%) | ||

| Vomiting of study drugs | |||

| After administration of dose 1 in clinic | 0/482 (0) | 1/468 (0.2) | .49 |

| After administration of dose 2 or 3 at home | 0/944 (0) | 2/915 (0.2) | .24 |

| Incidence measure | Events, No. (Incidence a) | ||

| Individual adverse events of any severityb | |||

| Abdominal pain | 85 (1.85) | 74 (1.69) | .57 |

| Cough | 69 (1.50) | 55 (1.25) | .34 |

| Headache | 39 (0.85) | 43 (0.98) | .51 |

| Anemia | 42 (0.91) | 40 (0.91) | .99 |

| Malaise | 27 (0.59) | 24 (0.55) | .80 |

| Diarrhea | 17 (0.37) | 14 (0.32) | .76 |

| Chills | 11 (0.24) | 11 (0.25) | .91 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 11 (0.24) | 11 (0.25) | .91 |

| Vomiting | 7 (0.15) | 7 (0.16) | .94 |

| Anorexia | 6 (0.13) | 4 (0.09) | .58 |

| Individual grade 3–4 adverse events | |||

| Anemia | 10 (0.22) | 7 (0.16) | .44 |

| Congenital anomaly | 1 (0.02) | 4 (0.09) | .22 |

| Stillbirth | 0 (0) | 1 (0.02) | .99 |

| Respiratory distress | 1 (0.02) | 0 (0) | .99 |

| Altered mental status | 0 (0) | 1 (0.02) | .99 |

| Elevated ALT level | 0 (0) | 1 (0.02) | .99 |

| All grade 3–4 adverse events | 12 (0.26) | 14 (0.32) | .74 |

| All serious adverse events | 4 (0.09) | 6 (0.14) | .55 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DP, dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aNumber per person-year at risk.

bData are limited to categories with ≥10 total events

DISCUSSION

In this double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, adding monthly DP to daily TMP-SMX did not reduce the risk of placental malarial infection or maternal malaria or improve birth outcomes among HIV-infected pregnant women taking ART in the setting of long-lasting ITNs and IRS. Overall, the burden of malaria was relatively low, compared with that in previous studies of HIV-infected and uninfected pregnant women conducted in the same study area prior to the implementation of IRS [12, 17]. Indeed, in this study, only 2 of 196 women had evidence of active infection by placental histopathologic analysis. Both regimens were well tolerated, and there were no statistically significant differences in the rates of the adverse events between the 2 arms.

DP has been shown to be highly effective for the treatment of malaria in pregnant and nonpregnant populations [19, 20] and for the prevention of malaria in children and nonpregnant adults [21, 22]. Two recent randomized, controlled trials have shown IPTp with DP to be more effective than SP at reducing the burden of malaria in HIV-uninfected pregnant women. In a preceding study by our group in Tororo, HIV-uninfected pregnant women were randomly assigned to receive IPTp with 3 doses of SP, 3 doses of DP, or monthly DP [12]. Compared with the 3-dose SP arm, monthly DP was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of symptomatic malaria, infection with malaria parasites, and maternal anemia during pregnancy and the risk of placental malarial infection measured at delivery. In addition, compared with the 3-dose DP arm, the monthly DP arm was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of symptomatic malaria and infection with malaria parasites during pregnancy, with a trend toward a lower risk of maternal anemia during pregnancy and placental malarial infection measured at delivery. In a study from Kenya, IPTp with DP was associated with a lower incidence of malarial infection and clinical malaria during pregnancy and a lower prevalence of malarial infection at delivery, compared with SP [11].

Given the excellent efficacy of DP and high prevalence of molecular markers of antifolate resistance in East Africa [23–25], it was unexpected that adding monthly DP to daily TMP-SMX did not reduce the burden of malaria in our study population. However, there were several factors that likely contributed to our negative findings. First, the burden of malaria in the daily TMP-SMX arm was strikingly low. In a previous study conducted in the same study area from December 2009 to March 2013 prior to the implementation of IRS, the risk of histopathologic detection of placental malarial infection among pregnant women receiving TMP-SMX prophylaxis and EFV-based ART was 33.3% as compared to 3.1% in this study [17]. The low burden of malaria in both arms of this study was likely a direct consequence of the recent IRS program, as demonstrated in our studies of malaria among children and HIV-uninfected pregnant women in the same study area [12, 26]. It is also likely that the high proportion of multigravidae in our study population contributed to the low incidence of placental malarial infection. Prior to the widespread use of ART, several studies showed that the proportion of cases of placental malarial infection attributable to HIV coinfection increases with parity, consistent with the impairment of parity-specific immunity due to HIV [3, 4]. Results from our study suggest that, among women who have well-controlled HIV infection and are receiving ART, loss of parity-specific immunity against placental malarial infection may be prevented. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic factors may have contributed to the lack of benefit of adding DP. In a complementary intensive pharmacokinetic study, including a subset of women from this study and HIV-uninfected nonpregnant controls, concentrations of dihydroartemisinin were 61% lower and piperaquine levels were 62% lower in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving EFV-based ART, compared with HIV-uninfected nonpregnant women (unpublished data).

An additional consideration is that daily TMP-SMX prophylaxis may provide a greater level of protection as compared to intermittent use of other antifolate drugs, such SP, even in the setting of high prevalence of markers of resistance. In randomized, controlled trials of chemoprevention among HIV-unexposed and -exposed infants from the same study site, monthly SP provided no significant protection from malaria, while daily TMP-SMX provided moderate protection [21, 27]. Studies of daily TMP-SMX versus IPTp with SP among HIV-infected pregnant women have provided mixed results. In an observational study from Malawi, daily TMP-SMX was associated with reduced malaria parasitemia and anemia as compared to IPTp with SP [28]. In a randomized, controlled trial from West Africa, where the prevalence of molecular markers of antifolate resistance tend to be lower than in East and Southern Africa, daily TMP-SMX was found to be noninferior to IPTp with SP [29].

Despite the lack of improvement in efficacy by adding monthly DP to daily TMP-SMX prophylaxis, there was no evidence of any increase in toxicity. The risk of vomiting of study drugs was similarly low in both treatment arms, and there were no significant differences in the rates of adverse events. Of particular concern was the risk of corrected QT prolongation, which was reported in a recent study among healthy Cambodian volunteers administered a compressed 2-day dosing regimen of DP [30]. In a subset of women who underwent electrocardiography in our study, DP was associated with a 15-msec increase in the corrected QT interval, but all measurements were within normal limits, and no clinical adverse events consistent with cardiotoxicity were observed.

In summary, the burden of malaria was relatively low among our population of HIV-infected pregnant women in the setting of daily TMP-SMX prophylaxis, EFV-based ART, ITNs, and IRS. The addition of IPTp with monthly DP appeared to be safe and well tolerated but did not provide any additional protection against malaria. Future studies of IPTp with DP among HIV-infected pregnant women should be considered in areas where the burden of malaria is higher.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the women who participated in the study, the dedicated study staff, practitioners at Tororo District Hospital, and members of the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health (grants P01 HD059454 and K12 HD052163).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Desai M, ter Kuile FO, Nosten F, et al. Epidemiology and burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flateau C, Le Loup G, Pialoux G. Consequences of HIV infection on malaria and therapeutic implications: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:541–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ned RM, Moore JM, Chaisavaneeyakorn S, Udhayakumar V. Modulation of immune responses during HIV-malaria co-infection in pregnancy. Trends Parasitol 2005; 21:284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. ter Kuile FO, Parise ME, Verhoeff FH, et al. The burden of co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and malaria in pregnant women in sub-saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2004; 71(2 Suppl):41–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among children, adolescents and adults. Recommendatinos for a public health approach http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/ctxguidelines.pdf Accessed December 2016.

- 6. Iriemenam NC, Shah M, Gatei W, et al. Temporal trends of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) drug-resistance molecular markers in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from pregnant women in western Kenya. Malar J 2012; 11:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ranson H, N’guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V. Pyrethroid resistance in African anopheline mosquitoes: what are the implications for malaria control? Trends Parasitol 2011; 27:91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Piola P, Nabasumba C, Turyakira E, et al. Efficacy and safety of artemether-lumefantrine compared with quinine in pregnant women with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: an open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:762–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rijken MJ, McGready R, Boel ME, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine rescue treatment of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in pregnancy: a preliminary report. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78:543–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White NJ. Intermittent presumptive treatment for malaria. PLoS Med 2005; 2:e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Desai M, Gutman J, L’lanziva A, et al. Intermittent screening and treatment or intermittent preventive treatment with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine versus intermittent preventive treatment with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the control of malaria during pregnancy in western Kenya: an open-label, three-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet 2015; 386:2507–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kakuru A, Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for the Prevention of Malaria in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:928–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamya MR, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, et al. Malaria transmission, infection, and disease at three sites with varied transmission intensity in Uganda: implications for malaria control. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:903–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katureebe A, Zinszer K, Arinaitwe E, et al. Measures of Malaria Burden after Long-Lasting Insecticidal Net Distribution and Indoor Residual Spraying at Three Sites in Uganda: A Prospective Observational Study. PLoS Med 2016; 13:e1002167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Division of AIDS (DAIDS) table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events, version 2.0 Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS, 2014. http://rsc.tech-res.com/Document/safetyandpharmacovigilance/DAIDS_AE_Grading_Table_v2_NOV2014.pdf Accessed 5 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hopkins H, González IJ, Polley SD, et al. Highly sensitive detection of malaria parasitemia in a malaria-endemic setting: performance of a new loop-mediated isothermal amplification kit in a remote clinic in Uganda. J Infect Dis 2013; 208:645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Natureeba P, Ades V, Luwedde F, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral treatment (ART) versus efavirenz-based ART for the prevention of malaria among HIV-infected pregnant women. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1938–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rogerson SJ, Hviid L, Duffy PE, Leke RF, Taylor DW. Malaria in pregnancy: pathogenesis and immunity. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7:105–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poespoprodjo JR, Fobia W, Kenangalem E, et al. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine treatment of multidrug resistant falciparum and vivax malaria in pregnancy. PLoS One 2014; 9:e84976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zani B, Gathu M, Donegan S, Olliaro PL, Sinclair D. Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for treating uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014:CD010927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bigira V, Kapisi J, Clark TD, et al. Protective efficacy and safety of three antimalarial regimens for the prevention of malaria in young Ugandan children: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med 2014; 11:e1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lwin KM, Phyo AP, Tarning J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of monthly versus bimonthly dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine chemoprevention in adults at high risk of malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1571–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matondo SI, Temba GS, Kavishe AA, et al. High levels of sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine resistance Pfdhfr-Pfdhps quintuple mutations: a cross sectional survey of six regions in Tanzania. Malar J 2014; 13:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mbonye AK, Birungi J, Yanow SK, et al. Prevalence of Plasmodium falciparum resistance markers to sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine among pregnant women receiving intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59:5475–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Naidoo I, Roper C. Drug resistance maps to guide intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in African infants. Parasitology 2011; 138:1469–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muhindo MK, Kakuru A, Natureeba P, et al. Reductions in malaria in pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes following indoor residual spraying of insecticide in Uganda. Malar J 2016; 15:437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kamya MR, Kapisi J, Bigira V, et al. Efficacy and safety of three regimens for the prevention of malaria in young HIV-exposed Ugandan children: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS 2014; 28:2701–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kapito-Tembo A, Meshnick SR, van Hensbroek MB, Phiri K, Fitzgerald M, Mwapasa V. Marked reduction in prevalence of malaria parasitemia and anemia in HIV-infected pregnant women taking cotrimoxazole with or without sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine intermittent preventive therapy during pregnancy in Malawi. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:464–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klement E, Pitché P, Kendjo E, et al. Effectiveness of co-trimoxazole to prevent Plasmodium falciparum malaria in HIV-positive pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manning J, Vanachayangkul P, Lon C, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a two-day regimen of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for malaria prevention halted for concern over prolonged corrected QT interval. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:6056–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]