Our study presents the first longitudinal data on incident childhood human herpesvirus 8 infection in a highly endemic area, Zambia in central-southern Africa. We confirm infection and transmission patterns within the household, most likely through shared feeding and eating practices.

Keywords: Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus, human herpesvirus 8, premastication, sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

Background

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) infection occurs in early childhood and is associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and risk for Kaposi sarcoma, but behaviors associated with HHV-8 transmission are not well described.

Methods

We enrolled and followed a prospective cohort of 270 children and their household members to investigate risk factors for HHV-8 transmission in Lusaka, Zambia.

Results

We report an incidence of 30.07 seroconversions per 100 child-years. Independent risk factors for HHV-8 incident infection included having a child who shared utensils with a primary caregiver (hazards ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49–7.14), having an increasing number of HHV-8–infected household members (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.09–2.79), and having ≥5 siblings/children in the household (HR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.03–4.88). Playing with >5 children a day was protective against infection (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, .33–0.89), as was increasing child age (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, .93–.99).

Conclusions

This is the first study to find a temporal association between limited child feeding behaviors and risk for HHV-8 infection. Child food- and drink-sharing behaviors should be included in efforts to minimize HHV-8 transmission, and households with a large number of siblings should receive additional counseling as childhood infections occur in the home context.

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) or Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the 8th known human herpesvirus, is known to be associated with the development of Kaposi sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma, and multicentric Castleman’s disease. In the United States and Western Europe, HHV-8 infection is uncommon in the general population, with higher prevalence in men who have sex with men (MSM) [1, 2]. In sub-Saharan Africa and Mediterranean regions, HHV-8 infection is endemic; however, risk factors for transmission are still not well characterized, although previous African studies have shown that HHV-8 infection may be associated with lower socioeconomic status [3, 4] and food-sharing behaviors. We have previously reported that Zambian children acquired HHV-8 infection early in life, with up to 40% of children becoming HHV-8–seropositive by 48 months of age [5]. Other Central African studies have shown that HHV-8 is primarily acquired in childhood [6].

Transmission of viruses via breast milk is well established—examples include human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and cytomegalovirus; however, HHV-8 DNA has not been readily isolated from breast milk [7–9], suggesting breast milk transmission of HHV-8 is uncommon for young children. Meanwhile, in HHV-8–seropositive mothers, high viral titers of HHV-8 are frequently isolated in saliva [8, 9]. In a previous study from a South African population, children of mothers with high viral load (>50000 copies/mL) in saliva were nearly 3 times more likely to be HHV-8–positive than children of mothers who did not shed HHV-8 in saliva [9]. Several studies have shown that transmission of HHV-8 occurs within households in endemic populations, most likely via saliva exchange, although these studies have not delineated risk factors [10–13].

Transmission patterns of HHV-8 have yet to be evaluated in longitudinal studies, which are necessary to assess the temporality of relationships between feeding exposures and incident infection. A cross-sectional rural Ugandan study observed food and/or sauce plate sharing within households as marginally associated with risk for HHV-8 infection in children aged <14 years [14]. The same study also observed a significantly increased risk of HHV-8 transmission to children in households that had ≥2 members who were HHV-8–positive, suggesting household transmission patterns similar to other studies [11].

The mode by which HHV-8 infection transmission occurs from infected mothers and other household members has public health importance, particularly in the context of populations with high rates of HIV-1 infection and poor adherence to antiretroviral therapies (ARTs), where infection with HHV-8 may subsequently lead to pediatric Kaposi sarcoma and associated co-morbidities. Indeed, our previous work has shown that ART reduces the HHV-8 incidence rate in HIV-1–infected children in endemic areas [15].

To investigate horizontal transmission of HHV-8 infection from within a household to children, we conducted a longitudinal observational study at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. Zambia has the highest incidence of KS in southern Africa, with a recent study finding a rate of 164/100000 person-years for patients initiated on ARTs and 59/100000 in children aged <16 years [16]. This is the first study to investigate a possible association between incident HHV-8 infection and food and drink-sharing-sharing practices in young, at-risk children.

METHODS

Study Setting

Details of the study design, rationale, and recruitment process for this study have been described in detail in a previously reported article [17]. In brief, participants were recruited from August 2004 to April 2007 at the study clinic in Lusaka, Zambia.

Inclusion criteria for enrollment were family with a child aged <2 years (the index child), residence in Lusaka, all family members willing to participate in annual follow-up visits, and the primary caregiver and index child willing to commit to 4-month follow-up visits. At each visit, a thorough physical examination was performed and new blood and saliva specimens were collected and tested for HHV-8 and HIV-1 infection. All family members were assessed at enrollment, with specimen collection for HHV-8 and HIV-1 infection, and annually thereafter until 48 months after enrollment.

As part of the study incentives, each participant was provided multivitamins and other medications when needed and a chance for their child to be followed-up by a reputable pediatrician. At all visits, subjects were provided with counseling about risk reduction for HIV-1. Study approval was granted by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Zambia and the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and study subjects provided signed informed consent

Data Collection and Measures

Questionnaires were designed as described in detail elsewhere [18]. These questionnaires address potential sources of blood or body fluids from household members to the index child, with detailed questions surrounding incidents that could possibly account for salivary exposure. Data collected included sociodemographics, medical conditions, laboratory testing (HIV-1, HHV-8), household living conditions, family structure, household lifestyle risk factors (e.g. sharing dental cleaning materials, eating with fingers from a common bowl, sharing drinks), and child caregiving behaviors (e.g. frequency and type of feeding, bathing, face washing, frequency of child sleepovers away from the home, etc).

Laboratory Testing

Sample Collection

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture from all members of the household within 8 months (mean, 2.3 months) of each other. HIV-1 testing was performed at the University Teaching Hospital clinic in Lusaka, Zambia, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated for polymerase chain reaction analysis for HIV-1–positive individuals.

Human Herpesvirus 8 Serology

Antibodies against HHV-8 latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) and HHV-8 lytic antigens was determined by immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) at a 1:40 starting dilution using a primary effusion lymphoma (BC-3) cell line negative for Epstein-Barr virus in our lab at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. The viral lytic cycle was induced by incubating BC-3 cells with 20 ng/mL of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA; Sigma) for 48 hours, as previously described [5]. The IFA signal was enhanced using a monoclonal mouse anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibody (CRL 1786) [19] as the secondary antibody, and DyLight 488-conjugated donkey anti-human antibody (Jackson Immuno Research) as the tertiary and detection antibody. A plasma sample was considered to be positive if 2 readers independently determined the sample to be positive on 2 independent IFA tests. Positive samples were tested on BJAB cells (an Epstein-Barr virus–negative and HHV-8–negative B-cell line), which performed the role of negative controls to rule out any nonspecific binding of antibodies to cells.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Serology

Plasma was screened for HIV-1 antibodies using both Capillus (Cambridge Biotech) and Determine (Abbott Laboratories) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A result was considered positive if both rapid test assays revealed a positive result. For children aged <18 months, early infant diagnosis using dried blood spot (DBS) was conducted. If children aged <18 months were found to be seropositive but no confirmatory DBS data were available, serostatus was based on serology results that were obtained at subsequent follow-up visits (≥18 months of age). If follow-up visits were not completed, the HIV-1 result was considered indeterminant.

Data Analysis

All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 13.0. Seroconverting children contributed HHV-8–free child-years at risk until testing positive for HHV-8. All data were right-censored at 48 months. Cox proportional hazards modeling was conducted to explore the strength and significant association between HHV-8 infection (outcome) and each individual characteristic (covariates). Hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values were calculated to identify risk factors for HHV-8 infection. Hazard ratios were calculated adjusting for age (at enrollment) and sex. Because of the collinearity between all of the feeding and food-sharing behaviors, we conducted multivariable analyses initially using each variable individually before including other feeding variables in a separate model. We also did not include number of HHV-8 infected household members variable with the number of siblings in the household as they were highly correlated with one another. Other demographic, health, and lifestyle variables that were significant at P < .05 in age- and sex-adjusted models were included in all multivariable analysis.

Missing data from follow-up visits were addressed by carrying forward the last known follow-up behavior.

RESULTS

Demographics and Incidence Rates of HHV-8 Seroconversion

A total of 270 total index children were enrolled in the current study cohort. Of the 270 children followed, 137 (50.7%) children seroconverted to be HHV-8–positive within the 4-year follow-up time of the study, and 133 (49.3%) remained negative. None of the HHV-8–infected children developed KS over the course of follow-up for the study.

Of the seroconverting children, at enrollment 11 of 137 (8.0%) were HIV-1–positive, and 12 of 133 (9.0%) were HIV-1–negative (Table 1). Significant differences between seroconverting children and non-seroconverting children included the following: Enrollment age in nonseroconverters was higher than in seroconverters (14.1 ± 6.5 vs 12.4 ± 6.2 mo; P = .02). HHV-8–seroconverting children had a higher number of household members than non-seroconverting children (5.3 ± 1.6 vs 4.8 ± 1.5; P = .02 (Table 1). There was no difference in education level or HIV-1 status between groups (Table 1). The primary caregiver of seroconverting children was more likely to be HHV-8–positive (50.7% vs 36.3%; P = .02), and there was a greater number of household members who were HHV-8–positive in seroconverting children (1.9 ± 1.3 vus 1.3 ± 1.1; P < .01) (Table 1), with 58.2% of seroconverting children having >2 household members who were HHV-8–positive at enrollment versus 40.9% of non-seroconverting children (P < .01).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Human Herpesvirus 8 Seroconverting and Nonseroconverting Children in Lusaka, Zambia, 2004–2009

| Characteristic | HHV-8 seroconverter (n = 137) | Nonseroconverter (n = 133) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Enrollment age of index child, mo | ||

| Range | 2–25 | 2–29 |

| Mean | 12.4* | 14.1* |

| Sex of index child | ||

| Male | 65 (47.4%) | 76 (57.1%) |

| Female | 72 (52.6%) | 57 (42.9%) |

| No. of household members | ||

| Range | 2–8 | 2–10 |

| Mean | 5.3* | 4.8* |

| Education of primary caregiver | ||

| None | 15 (10.9%) | 11 (8.3%) |

| Primary school | 73 (53.3%) | 78 (58.6%) |

| Secondary school | 49 (35.8%) | 44 (33.1%) |

| HIV-1 serology at enrolment | ||

| Index child HIV-1+ | 11/137 (8.0%) | 12/133 (9.0%) |

| Primary caregiver HIV-1+ | 56/137 (40.9%) | 65/133 (48.9%) |

| ≥1 other household member HIV-1+ | 69/137 (50.4%) | 71/133 (53.4%) |

| HHV-8 serology at enrolment | ||

| Primary caregiver HHV-8+ | 67/132a (50.7%)* | 45/124a (36.3%)* |

| ≥1 other household member HHV-8+ (other than primary caregiver) | 114/134a (85.1%)** | 90/127a (70.9%)** |

| ≥2 other household members HHV-8+ (other than primary caregiver) |

78/134 (58.2%)** |

52/127 (40.9%)** |

| Number of HHV-8+ household members | ||

| Range | 0–7 | 0–4 |

| Mean | 1.9** | 1.3** |

Abbreviations: HHV-8, human herpesvirus 8; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1;

aNumbers do not match total due to discrepant or unavailable serology at enrollment.

*P < .05

**P < .01

The incidence rate of HHV-8 seroconversion in the total cohort of 270 children was 30.07 per 100 child-years, based on a total of 455.67 child-years of follow-up. We examined crude incidence rates by primary caregiver and child HIV-1 status, finding an incidence rate of 29.49 per 100 child-years for HIV-1–positive children and an incidence rate of 30.12 per 100 child-years for HIV-1–negative children. If the caregiver was HIV-1–positive, incidence rates were slightly lower (25.26 per 100 child-years) than if the caregiver was HIV-1–negative (34.62 per 100 child-years). These results did not take into consideration the child’s HIV-1 status. However, the findings were similar when we examined only the HIV-1–negative children. Incidence rates were 24.41 per 100 child-years for HIV-1–negative children with HIV-1–positive caregivers and 34.62 per 100 child-years for HIV-1–negative children with HIV-1–negative caregivers. The incidence was much higher among children aged <12 months (40.11 per 100 child-years vs 22.67 in children aged 12–17 mo and 24.06 in children aged ≥18 mo).

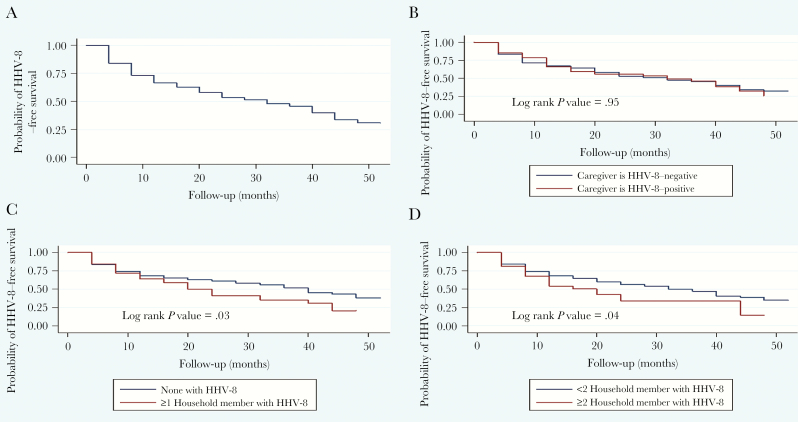

Figure 1 presents the probability curves as obtained from Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Figure 1A represents the total cohort, showing the probability of annual HHV-8 infection occurring over the 5-year time span. Figure 1B shows the probability of a child with an HHV-8–positive caregiver becoming HHV-8 infected (log rank P = .95). The probability curves seen in Figure 1C display the probability of a child withone or more household members who are HHV-8–positive seroconverting (log rank P = .03), and Figure 1D displays the probability of a child with 2 or more household members who are HHV-8–positive seroconverting (log rank P = .04).

Figure 1.

Results from Kaplan-Meier survival analysis estimating the probability of a child seroconverting to become positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) in Lusaka, Zambia, 2004–2009. Results are represented by the total cohort (n = 270) (A); HHV-8 status of the primary caregiver at enrollment (B); HHV-8 status of the household members at enrollment (≥1 infected) (C); and HHV-8 status of the household members at enrollment (≥2 infected) (D). Abbreviation: HHV-8, human herpesvirus 8.

Prevalence of Food Sharing, Feeding Behaviors, and Health Hygiene in Cohort

We found a low overall frequency of food sharing and feeding behaviors that involved the exchange of saliva. Only 1.1% (n = 3/270) stated that the primary caregiver or another caregiver premasticated the food before feeding it to the child. A high percentage were currently or had been breastfeeding (78.1% [n = 211/270] current or previous; 18.5% [n = 50/270] current and 59.6% [n = 161/270] prior breastfeeding) (Table 2). Less than 10% stated that they taste-tested food before feeding it to the child (6.3%), 8.9% blew on the food before feeding the child, 3% used a common bowl when eating, and 3.7% used common utensils. A similar low percentage shared drinks (4.8%), observed the child sharing food in the household (6.7%), and observed food exchange between children (6.3%). A much higher percentage stated that they cleaned the child’s face twice or more daily (32.6%), with a low percentage of caregivers brushing children's teeth (4.1%), and 28.5% reporting that their child plays with more than five children.

Table 2.

Total Prevalence of Feeding and Food-Sharing, Health Hygiene, and Lifestyle Behaviors in Cohort

| Behaviors | No./Total (%) |

|---|---|

| Feeding and food sharing | |

| Premasticate food (primary caregiver or anyone else) | 3/270 (1.1) |

| Any prior or current breastfeeding | 211/270 (78.2) |

| Taste-test food before feeding (primary caregiver) | 15/570 (5.6) |

| Anyone else taste test food before feeding child | 17/270 (6.3) |

| Blow on food before feeding (primary caregiver) | 24/270 (8.9) |

| Anyone blow on food before feeding child | 24/270 (8.9) |

| Child uses a common bowl in eating | 8/270 (3.0) |

| Share utensils (between primary caregiver and child) | 8/270 (3.0) |

| Share utensils (with anyone) | 10/270 (3.7) |

| Share drinks (with caregiver) | 11/270 (4.1) |

| Share drinks with anyone | 13/270 (4.8) |

| Share food with child (primary caregiver) | 13/270 (4.8) |

| Children in household share food | 18/270 (6.7) |

| Neighbors share sweets with child | 6/270 (2.2) |

| Observe exchange of food between children | 17/270 (6.3) |

| Health hygiene and lifestyle | |

| Child cleans face twice or more daily | 88/270 (32.6) |

| Child’s nail biting (used to clip them) | 7/270 (2.6) |

| Toothbrushing (yes) | 11/270 (4.1) |

| Lifestyle and household | |

| Child plays with >5 children | 77/270 (28.5) |

| Child plays with >5 children under 5 years | 72/270 (26.7) |

| Child sleeps away from home in last 6 months | 5/270 (1.9) |

Risk Factors for Incident Human Herpesvirus 8 Infection

None of the socioeconomic indicators (electricity, number of rooms in house, persons per room, education level of the caregiver) was associated with incident infection when adjustment was made for enrollment age and sex (Table 3). Increasing child age at enrollment was protective (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, .93–.99), with children aged 12–17 months having reduced risk (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, .38–.91) compared with those aged <12 months. Similarly, those aged 18–29 months (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, .41–.94) had reduced risk compared with those aged <18 months. Having ≥5 children in the household (either siblings or other, extended family members - e.g. cousins) was associated with increased risk for incident infection (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.11–5.21) (Table 3). Reporting that the child plays with >5 children on a daily basis was associated with decreased risk of infection both in bivariate and adjusted analysis (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, .33–.90); playing with younger children (<5 years) was not associated with increased risk (Table 3).

Table 3.

Socioeconomic, Sociodemographic, and Lifestyle Risk Factors for Infection (Bivariate and Sex- and Age-Adjusted)

| Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic | ||

| Have electricity in house | 1.19 (.74–1.90) | 1.10 (.68–1.76) |

| Rooms in house (number) | 1.01 (.83–1.25) | 1.04 (.84–1.28) |

| Mud/plastic walls in house (vs brick/concrete) | 1.33 (.49–3.62) | 1.21 (.43–3.30) |

| Persons per room in house (household density) | 1.06 (.94–1.19) | 1.04 (.92–1.18) |

| Primary caregiver education level | ||

| No education | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Primary | 0.77 (.43–1.36) | 0.79 (.44–1.41) |

| Secondary | 0.70 (.38–1.27) | 0.70 (.38–1.27) |

| Sociodemographic | ||

| Male | 0.75 (.44–1.37) | 0.78 (.44–1.39) |

| Age at enrollment (continuous) | 0.96 (.93–.99)* | 0.96 (.93–.99)* |

| Number of siblings or children in household | 1.10 (.97–1.25) | 1.11 (.97–1.27) |

| ≥ 5 siblings or children in household | 2.08 (.97–4.47) | 2.41 (1.11–5.21)** |

| Lifestyle and household | ||

| Child plays with >5 children | 0.52 (.32–0.86)** | 0.54 (.33–.90)** |

| Child plays with >5 children aged <5 y | 0.75 (.46–1.22) | 0.79 (.49–1.29) |

| Child sleeps away from home in last 6 mo | 0.77 (.11–5.53) | 0.80 (.11–5.72) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

*P < .01.

**P < .05.

A couple of the behaviors associated with exposure to saliva through feeding or food sharing were associated with increased risk for HHV-8 seroconversion (Table 4). Risk factors for HHV-8 seroconversion include having the primary caregiver blow on the food before feeding to the child (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.03–3.42) and sharing utensils with the primary caregiver (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.11–5.29) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Feeding and Food-Sharing Risk Factors Associated With Seroconversion (Bivariate and Age- and Sex-Adjusted)

| Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Presmasticate food (primary caregiver or anyone else) | 1.16 (0.28–4.74) | 1.37 (0.33–5.65) |

| Any prior or current breastfeeding | 1.82 (0.89–3.73) | 1.50 (0.73–3.11) |

| Current breastfeeding | 1.36 (0.86–2.14) | 1.08 (0.66–1.75) |

| Taste test food before feeding (primary caregiver) | 1.12 (0.51–2.42) | 1.27 (0.58–2.76) |

| Anyone else taste test food before feeding child | 2.01 (0.63–6.36) | 2.20 (0.69–7.03) |

| Blow on food before feeding (primary caregiver) | 1.61 (.89–2.91) | 1.88 (1.03–3.42)* |

| Anyone blow on food prior to feeding child | 1.01 (.41–2.49) | 1.16 (0.47–2.88) |

| Child useS a common bowl in eating | 1.60 (.70–3.66) | 1.84 (.86–4.61) |

| Share utensils (with primary caregiver) | 2.05 (.95–4.44) | 2.42 (1.11–5.29)* |

| Share utensils (with anyone) | 1.49 (.65–3.43) | 1.70 (.73–3.92) |

| Share drinks (with primary caregiver) | 1.15 (.52–2.49) | 1.30 (.59–2.86) |

| Share drinks (with other household members) | 1.23 (.56–2.68) | 1.46 (.66–3.22) |

| Share drinks (with anyone) | 0.94 (.30–2.97) | 1.16 (.36–3.70) |

| Share food with child (primary caregiver by placing in mouth or reducing size) | 1.33 (.50–2.59) | 1.30 (.57–3.00) |

| Share food with child (any household member by placing in mouth or reducing size) | 1.29 (.60–2.79) | 1.54 (.71–3.37) |

| Children in household share food | 1.33 (.66–2.65) | 1.62 (.80–3.26) |

| Neighbors share sweets with child | 0.86 (.27–2.72) | 1.002 (.32–3.19) |

| Toothbrushing | 0.25 (.04–1.80) | 0.31 (.04–2.23) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

*P < .05.

Although HIV-1 serostatus of the child or household members was not associated with HHV-8 seroconversion, having a household member who was HHV-8 infected at enrollment was associated with infection (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.06–1.54) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Health and Hygiene Risk Factors Associated with Seroconversion (Age- and Sex-Adjusted)

| Risk factors | HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV serostatus | ||

| Any household member HIV+ | 0.83 (.59–1.16) | 0.84 (.60–1.17) |

| Child HIV+ | 0.96 (.52–1.79) | 1.10 (.59–2.06) |

| Any household member HIV+ | 0.83 (.59–1.16) | 0.84 (.60–1.17) |

| Primary caregiver HIV+ | 0.76 (.54–1.06) | 0.74 (.53–1.04) |

| HHV-8 serostatus | ||

| Number of other household members HHV-8+ | 1.29 (1.08–1.55)* | 1.28 (1.06–1.54)** |

| Caregiver HHV-8+ at enrollment | 1.02 (.70–1.50) | 1.06 (.72–1.55) |

| Health hygiene | ||

| Child cleans face twice or more daily | 0.95 (.55–1.63) | 1.10 (.71–1.70) |

| Child bathes twice or more daily | 1.03 (.63–1.69) | 1.02 (.69–1.49) |

| Bites child’s nails (uses mouth to clip them) | 0.65 (.16–2.66) | 0.69 (.17–2.81) |

| Toothbrushing (yes) | 0.25 (.04–1.80) | 0.31 (.04–2.23) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HHV-8, human herpesvirus 8; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio.

*P < .01.

**P < .05.

Multivariable Analysis

In multivariable analysis, having a child who shares utensils with a primary caregiver was associated with incident infection (HR, 2.33; 95% CI, 1.01–5.39) as was having HHV-8–positive household members (HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.09–2.79), and increasing child age was protective (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, .93–.99) as was playing with >5 children (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, .33–.89) (Table 6). When substituting blowing on food by a primary caregiver for sharing utensils, this behavior neared statistical significance in association with incident infection (HR, 1.73; 95% CI, .92–3.23). When substituting having ≥5 siblings/children in the household with number of HHV-8–positive household members at enrollment, the hazard ratio for incident infection was 2.24 (95% CI, 1.03–4.88).

Table 6.

Multivariable Risk Factors for Incident Human Herpesvirus 8 Infection

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Child sex (male) | 0.77 (.55–1.10) | .39 |

| Child age at enrollment | 0.96 (.93–.99) | <.01 |

| Caregiver shares utensils | 2.33 (1.01–5.39) | .048 |

| Child plays with > 5 children | 0.54 (.33–.89) | .02 |

| Household members HHV-8+ at enrollment | 1.27 (1.09–2.79) | .01 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HHV-8, human herpesvirus 8; HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to find a longitudinal association between select feeding behaviors and incident HHV-8 infection in a cohort of young children in Zambia, an area that is endemic for HHV-8 infection and KS. Our earlier studies in Zambia have shown that there is high incidence of HHV-8 infection in early childhood [5], which made our study ideal to assess household risk factors for childhood incident infection. In the present study we observed a high incidence rate of 30.07 infections per 100 child-years. This confirms our earlier observations that HHV-8 infection is acquired during childhood in Zambia and that adult seroprevalence levels may be reached relatively early in this population.

One of the major strengths of this study is that information on a range of behaviors that increase the risk of salivary transmission and exposures in the household was collected via questionnaires to identify specific risk factors that may be associated with an increased risk of acquisition of HHV-8 infection, and these were evaluated longitudinally in relation to HHV-8 infection.

Feeding Behaviors Involving Saliva Exchange, Child Age, and Risk of Infection

We found some evidence for risk associated with a couple of feeding and food-sharing behaviors associated with saliva exchange (sharing utensils and blowing on food before feeding). Our study is the first study to find these associations using a longitudinal design. Other studies have had negative findings, possible due to confounding, which may be more difficult to assess in cross-sectional studies. For example, a cross-sectional study from rural Uganda found a borderline significant association in risk of infection among those who shared a food and/or sauce plate (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% CI, .99–4.30) [14]. We also found no association with premastication and other food-sharing behaviors in this longitudinal study, in addition to our previous cross-sectional study [20].

Interestingly, we had an overall low frequency of food-sharing and feeding behaviors involving saliva exchange, with <10% and in many cases <5% of the participants stating that they had ever engaged in these practices, including only 1.1% who stated that they ever premasticated the food before feedings. Our results contrast with other sub-Saharan African studies where a much higher percentage of mothers and other caregivers surveyed state that they had engaged in these practices [3, 21, 22]. It is possible that regional sub-Saharan African cultural differences may account for some of the divergent patterns in frequency, and premastication may not be a common practice in Zambia. Alternatively, the way the questions were phrased in our questionnaire may have resulted in under-reporting of practices.

We also found that infants and preschool children were at increased risk of incident infection compared with older preschool children. It is likely that risk for infection tapers off as children get older and change behaviors and hygiene practices. Our findings are similar to those reported by Butler et al for South Africa where most of the HHV-8 infection occurs in young children aged <2 years [23]. Prevention efforts and recommendations for feeding practices should be focused on the youngest children.

Exposure to Other Children and Protection Against Infection

In contrast with other cross-sectional sub-Saharan African studies, we did not find any association between incident infection and number of household members or crowding indices [24, 25]. However, we did find that increasing number of siblings and children in the household, albeit not total household size, was associated with incident infection and correlated with increasing number of HHV-8 household members. Meanwhile, ours is the first longitudinal study to find that exposure to other children for play was protective against infection. It is possible that play with other children, particularly if outdoor play, indicates less indoor exposure, less illness, and less opportunity for herpesvirus infection such as HHV-8 in the household. Furthermore, limited play with other children and increasing number of siblings are independently associated with risk for HHV-8 infection, suggesting, again, that most of the transmission likely occurs in the household context. Although our previous cross-sectional study of Zambian children did not find any association with crowding or number of household members and prevalent infection [19], we did not assess the association between siblings or outdoor play in that study.

Socioeconomic Status and Risk of Infection

We did not find any associations between socioeconomic status as indicated by in-house electricity, building material used in the home, household density, or caregiver education level. Previous studies have found that lower socioeconomic status is associated with increased risk for infection, including the study from Entebbe, Uganda, that found a protective effect with higher maternal education level [26], as well as an earlier Ugandan study [27] and a study from South Africa [28]. It is possible that our study was underpowered to find an effect based on differences in socioeconomic status of our population given the relative homogeneity of those surveyed. Future studies, which evaluate socioeconomic status as a risk factor, should use standard indictors or interpret results with caution.

Human Herpesvirus 8 Seropositivity for Household Members and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

We found that increasing number of household members with HHV-8–positive serostatus was associated with incident child infection, similar to many other previous African studies [12, 23, 26, 27]. These are important findings because it may be essential to advise households with multiple members with HHV-8 infections to abstain from food-sharing practices when young, uninfected children are present in the household, particularly in the context of HIV-1 and limited adherence or access to ARTs. Interestingly, we did not find that there was increased risk associated with the caregiver being HHV-8–positive, suggesting that there is more likely horizontal transmission in households. However, the food-sharing practices that were associated with increased risk for transmission were those that were reported by the caregiver.

This study was not designed to study the effect of HIV-1, and only a very small percentage of our participants were HIV infected; thus the study was underpowered to discern noticeable differences between groups. Moreover, even though we did not inquire about ART status of our HIV-positive index children, it is likely that a number of them may have been exposed to ART because it was being introduced into the country at the time of study enrollment and follow-up.

Implications of Findings

Our study suggests specific routes for HHV-8 transmission in young children, including sharing utensils and possibly blowing on food before food sharing. In endemic areas of sub-Saharan Africa, including Zambia, where HIV-1 is commonly associated with HHV-8 [29] and ART adherence is still a concern [30, 31], it may be particularly important to counsel high-risk families with at-risk young infants and children. Furthermore, data from HIV patients on ART and cancer registries from sub-Saharan Africa indicate that the incidence of KS, including pediatric KS, remains high even though it is decreasing [32], suggesting the need for the development of public health programs focused on recommending against food sharing to reduce HHV-8 infection.

Notes

Funding. This work was supported by grants to C. W. from National Institute of Health Fogarty International Training Program (D43 TW01492); National Cancer Institute (CA75903); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (T32 A1060547) and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences (P30 GM103509). K.C. was a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 Fellow.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Melbye M, Cook PM, Hjalgrim H et al. . Risk factors for Kaposi’s-sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) seropositivity in a cohort of homosexual men, 1981–1996. Int J Cancer 1998; 77:543–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Engels EA, Atkinson JO, Graubard BI et al. . Risk factors for human herpesvirus 8 infection among adults in the United States and evidence for sexual transmission. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Butler LM, Neilands TB, Mosam A, Mzolo S, Martin JN. A population-based study of how children are exposed to saliva in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: implications for the spread of saliva-borne pathogens to children. Trop Med Int Health 2010; 15:442–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wojcicki JM, Newton R, Urban M et al. . Low socioeconomic status and risk for infection with human herpesvirus 8 among HIV-1 negative, South African black cancer patients. Epidemiol Infect 2004; 132:1191–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minhas V, Crabtree KL, Chao A et al. . Early childhood infection by human herpesvirus 8 in Zambia and the role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coinfection in a highly endemic area. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168:311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gessain A, Mauclère P, van Beveren M et al. . Human herpesvirus 8 primary infection occurs during childhood in Cameroon, Central Africa. Int J Cancer 1999; 81:189–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamprecht K, Maschmann J, Vochem M, Dietz K, Speer CP, Jahn G. Epidemiology of transmission of cytomegalovirus from mother to preterm infant by breastfeeding. Lancet 2001; 357:513–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brayfield BP, Kankasa C, West JT et al. . Distribution of Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus/human herpesvirus 8 in maternal saliva and breast milk in Zambia: implications for transmission. J Infect Dis 2004; 189:2260–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dedicoat M, Newton R, Alkharsah KR et al. . Mother-to-child transmission of human herpesvirus-8 in South Africa. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:1068–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mbulaiteye SM, Pfeiffer RM, Whitby D, Brubaker GR, Shao J, Biggar RJ. Human herpesvirus 8 infection within families in rural Tanzania. J Infect Dis 2003; 187:1780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borges JD, Souza VA, Giambartolomei C et al. . Transmission of human herpesvirus type 8 infection within families in American indigenous populations from the Brazilian Amazon. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:1869–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plancoulaine S, Abel L, van Beveren M et al. . Human herpesvirus 8 transmission from mother to child and between siblings in an endemic population. Lancet 2000; 356:1062–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Plancoulaine S, Abel L, Trégouët D et al. . Respective roles of serological status and blood specific antihuman herpesvirus 8 antibody levels in human herpesvirus 8 intrafamilial transmission in a highly endemic area. Cancer Res 2004; 64:8782–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Butler LM, Were WA, Balinandi S et al. . Human herpesvirus 8 infection in children and adults in a population-based study in rural Uganda. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:625–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olp LN, Minhas V, Gondwe C et al. . Effects of antiretroviral therapy on Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) transmission among HIV-infected Zambian children. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015; 107:pii:djv189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rohner E, Valeri F, Maskew M et al. . Incidence rate of Kaposi sarcoma in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in Southern Africa: a prospective multicohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014; 67:547–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minhas V, Crabtree KL, Chao A et al. . The Zambia Children’s KS-HHV8 Study: rationale, study design, and study methods. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 173:1085–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wojcicki JM, Kankasa C, Mitchell C, Wood C. Traditional practices and exposure to bodily fluids in Lusaka, Zambia. Trop Med Int Health 2007; 12:150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reimer CB, Phillips DJ, Aloisio CH et al. . Evaluation of thirty-one mouse monoclonal antibodies to human IgG epitopes. Hybridoma 1984; 3:263–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Crabtree KL, Wojcicki JM, Minhas V et al. . Risk factors for early childhood infection of human herpesvirus-8 in Zambian children: the role of early childhood feeding practices. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014; 23:300–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Auer-Hackenberg L, Thol F, Akerey-Diop D et al. . Short report: premastication in rural Gabon—a cross-sectional survey. J Trop Pediatr 2014; 60:154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maritz ER, Kidd M, Cotton MF. Premasticating food for weaning African infants: a possible vehicle for transmission of HIV. Pediatrics 2011; 128:e579–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Butler LM, Dorsey G, Hladik W et al. . Kaposi sarcoma—associated herpesvirus (KSHV) seroprevalence in population-based samples of African children: evidence for at least 2 patterns of KSHV transmission. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:430–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caterino-de-Araujo A, Manuel RC, Del Bianco R et al. . Seroprevalence of human herpesvirus infection in individuals from health care centers in Mozambique: potential for endemic and epidemic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Med Virol 2010; 82: 1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mbulaiteye SM, Biggar RJ, Pfeiffer RM et al. . Water, socioeconomic factors, and human herpesvirus 8 infection in Ugandan children and their mothers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38:474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wakeham K, Webb EL, Sebina I et al. . Risk factors for seropositivity to Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus among children in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:228–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mbulaiteye SM, Biggar RJ, Pfeiffer RM et al. . Water, socioeconomic factors, and human herpesvirus 8 infection in Ugandan children and their mothers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 38:474–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sitas F, Carrara H, Beral V et al. . Antibodies against human herpesvirus 8 in black South African patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1863–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rohner E, Wyss N, Heg Z et al. . HIV and human herpesvirus 8 co-infection across the globe: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2016; 138:45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sutcliffe CG, van Djik JH, Muleka M, Munsanje J, Thuma PE, Moss WJ. Delays in initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children in rural Zambia. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2016; 35:e107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Denison JA, Koole O, Tsui S et al. . Incomplete adherence among treatment-experienced adults on antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. AIDS 2015; 29:361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stefan DC. Patterns of distribution of childhood cancer in Africa. J Trop Pediatr 2015; 61:165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mancuso R, Brambilla L, Agostini S et al. . Intrafamiliar transmission of Kaposi’s sarcoma–associated herpesvirus and seronegative infection in family members of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma patients. J Gen Virol 2011; 92:744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]