Abstract

Background.

The outbreak of novel avian H7N9 influenza virus infections in China in 2013 has demonstrated the continuing threat posed by zoonotic pathogens. Deciphering the immune response during natural infection will guide future vaccine development.

Methods.

We assessed the induction of heterosubtypic cross-reactive antibodies induced by H7N9 infection against a large panel of recombinant hemagglutinins and neuraminidases by quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and novel chimeric hemagglutinin constructs were used to dissect the anti-stalk or -head humoral immune response.

Results.

H7N9 infection induced strong antibody responses against divergent H7 hemagglutinins. Interestingly, we also found induction of antibodies against heterosubtypic hemagglutinins from both group 1 and group 2 and a boost in heterosubtypic neutralizing activity in the absence of hemagglutination inhibitory activity. Kinetic monitoring revealed that heterosubtypic binding/neutralizing antibody responses typically appeared and peaked earlier than intrasubtypic responses, likely mediated by memory recall responses.

Conclusions.

Our results indicate that cross-group binding and neutralizing antibody responses primarily targeting the stalk region can be elicited after natural influenza virus infection. These data support our understanding of the breadth of the postinfection immune response that could inform the design of future, broadly protective influenza virus vaccines.

Keywords: influenza, H7N9, cross-reactive antibody, stalk-reactive, universal influenza vaccine.

A novel avian H7N9 virus crossed the species barrier and caused a zoonotic epidemic in China in 2013 [1, 2]. This virus has reemerged repeatedly in a seasonal pattern, and to date >600 human cases of avian influenza A (H7N9) infection have been reported [3]. Because the virus continues to circulate in poultry, it still poses a serious public health threat [4].

While humans are frequently exposed to seasonal influenza viruses, infections with avian influenza viruses are rare. Although 4 outbreaks of human H7 subtyped influenza virus (H7N7, H7N2, and H7N3) were reported before 2013 [5–7], the magnitude and breadth of the serological neutralizing antibody (nAb) responses elicited during natural infection remain unknown [8, 9]. Our previous research showed that a heterosubtypic, broadly neutralizing antibody response could be boosted by 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination and infection [10–12]. It has been hypothesized that sequential exposure of humans to hemagglutinins with divergent globular head domains but conserved stalk domains could refocus the immune responses to broadly neutralizing epitopes in the stalk [13, 14]. Whether booster immunizations with divergent H7 influenza virus strains in the general human population can induce universally protective antibodies is still unknown. To date, the vast majority of stalk-reactive antibodies isolated from mice and humans neutralize group 1 hemagglutinin (HA)-expressing influenza viruses. The polyclonal humoral responses to conserved epitopes that are potentially found in group 2 HA stalk domains remain poorly characterized, with limited data for induction of these antibodies by natural infection [15, 16]. It was unclear whether H7N9 infection could induce heterosubtypic or broadly cross-reactive antibody responses as well, specifically in the context of preexisting immunity to seasonal influenza virus strains.

Therefore, we initiated experiments to investigate the cross-reactive antibody response in paired early and late time point sera of 18 H7N9-infected patients. Furthermore, we used assays based on HA head constructs and chimeric HAs to quantitatively assess the induction of head- or stalk-reactive antibodies upon H7N9 infection in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Serum Samples

Serum samples from 18 2013 H7N9-infected patients hospitalized at Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center were collected at the early or late infection stage as indicated in Table 1. Noninfected control serum samples were obtained from age-matched individuals who had not experienced recent influenza virus infections (Supplementary Table 3). Longitudinal serial serum samples were collected from 6 individuals. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The overall study was reviewed and approved by the SHAPHC Ethics Committee (approval no. 2016-S021-01).

Table 1.

Demographic Information, Sample Collection, and Clinical Outcomes of H7N9-Infected Patients

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | nAb and HAI | bAb(days)a | Clinical Outcomeb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | Early | Late | ||||

| 1 | 58 | M | 13 | 35 | 13 | 20 | Death |

| 2 | 78 | M | 11 | 32 | 11 | 31 | 31 |

| 3 | 56 | M | 9 | 30 | 10 | 22 | Death |

| 4 | 81 | F | 6 | 31 | 6 | 31 | 23 |

| 5 | 67 | M | 11 | 23 | 9 | 21 | 23 |

| 6 | 74 | F | 8 | 22 | 8 | 22 | 21 |

| 7 | 62 | M | 9 | 36 | 8 | 35 | 35 |

| 8 | 75 | F | 10 | 34 | 10 | 30 | 33 |

| 9 | 79 | F | 9 | 35 | 8 | 27 | 27 |

| 10 | 67 | M | 10 | 29 | 9 | 28 | 27 |

| 11 | 65 | M | 9 | 18 | 8 | 17 | 18 |

| 12 | 74 | M | 10 | 22 | 10 | 21 | 22 |

| 13 | 74 | M | 10 | 12 | NA | NA | Death |

| 14 | 68 | M | 8 | 18 | NA | NA | 18 |

| 15 | 53 | M | 6 | 13 | NA | NA | 14 |

| 16 | 47 | M | 7 | 15 | NA | NA | 17 |

| 17 | 88 | M | 10 | 20 | NA | NA | Death |

| 18 | 80 | M | 16 | 18 | NA | NA | Death |

Abbreviations: bAb, binding antibody; F, female; HAI, hemagglutination inhibition; M, male; NA, not analyzed; nAb, neutralizing antibody.

aMatched serum samples were collected for each patient at indicated days after onset of symptoms.

bDischarged after days of onset or death.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Recombinantly produced and purified HA and neuraminidase (NA) proteins were used as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) substrates. Proteins were produced using the baculovirus expression system as described before [17, 18]. Detailed information regarding strains and subtypes is listed in Supplementary Table 1. ELISAs were performed as described before. For endpoint titers, the cutoff was considered to be the mean optical density (OD) measured for secondary antibody-only wells plus 3 standard deviations. For competition ELISA assays, plates of 100-µL monoclonal mouse anti-stalk antibody GG3 at a concentration of 10 µg/mL were incubated for 1 hour before incubation with serial diluted serum as described before [19, 20].

Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay

All serum samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme to inactivate nonspecific inhibitors before hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay testing. Two-fold serially diluted sera were incubated with 4 HA units of live virus (A/Shanghai/4664T/2013(H7N9)), pseudotyped viruses [21] (Supplementary Table 2), or formalin-inactivated low pathogenic H5N1 (6:2 reassortant with HA and NA from A/Vietnam/1203/2004 and the remaining genes from A/PR/8/34; the multibasic cleavage site of the H5 HA was removed) at room temperature for 15 minutes, then 50 μL of standardized 1% guinea pig red blood cells (RBCs) were added, and 0.5% chicken RBCs were used to place guinea pig RBCs for H5N1 [22]. After 1 hour of incubation, HAI results were interpreted. The HAI titer was defined as the reciprocal of the last dilution resulting in complete HAI.

Neutralization Assay

All pseudotyped viruses were provided by VacDiagn Biotechnology (Supplementary Table 2) and prepared as described previously [11]. Two-fold serially diluted sera were incubated with 200 50% Tissue culture Infective Dose (TCID50) pseudoviruses at a final volume of 100 μL at 37°C for 1 hour, then the mixture was added to culture of MDCK (Madin-Darby canine kidney) cells at 80% confluency. After overnight incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and cultured in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium for 48 hours. Infected cells were lysed by luciferase lysis buffer, and relative luminescence units (RLUs) were measured by luciferase substrate. Neutralization percentage was calculated as (average RLUs of virus control wells − RLUs of serum sample at a given dilution) / average RLUs of virus control wells. The 80% inhibitory concentration (IC80) titer was expressed as the reciprocal of the serum dilution required to reduce RLUs by 80%.

Effect of Oseltamivir on Neutralization Against Pseudoviruses in Serum

Sera from 4 H7N9-uninfected people were incubated with different concentrations of oseltamivir for 30 minutes at 37°C. Then SH13 H7 pseudoviruses were added and incubated for 1 additional hour. The subsequent procedures were the same as in the neutralization assays above. The final dilution of serum samples was 1:40.

Removal of Immunoglobin G and H7 Hemagglutinin Absorption

Sera from 4 H7N9-infected patients at the late time point were diluted and then incubated with H7 HA protein (A/Shanghai/1/2013) overnight at 4°C at a concentration of 1:1. The diluted sera without the treatment of H7 HA protein were used as controls. After treatment, the sera were tested for endpoint titers of H3, H5, H6, and H7 HA proteins by ELISA. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) in sera samples was removed by using Protein A/G by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 50 μL of Protein A/G Agarose were added to 50-μL serum samples and incubated at 4°C overnight. Treated sera were centrifuged at 1000 g, then the IgG depleted supernatants were carefully harvested.

Statistical Analysis and Data Plotting

Geometric mean titers (GMTs) of nAbs or HAI titers were calculated by assigning a titer of half of the lowest dilution to samples with no detectable antibodies at the starting dilution. All statistical analyses and data plotting were performed in GraphPad Prism software. Statistical analysis between groups was analyzed with at test, and P < .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Homologous H7N9 Antibody Responses in H7N9-Infected Patients

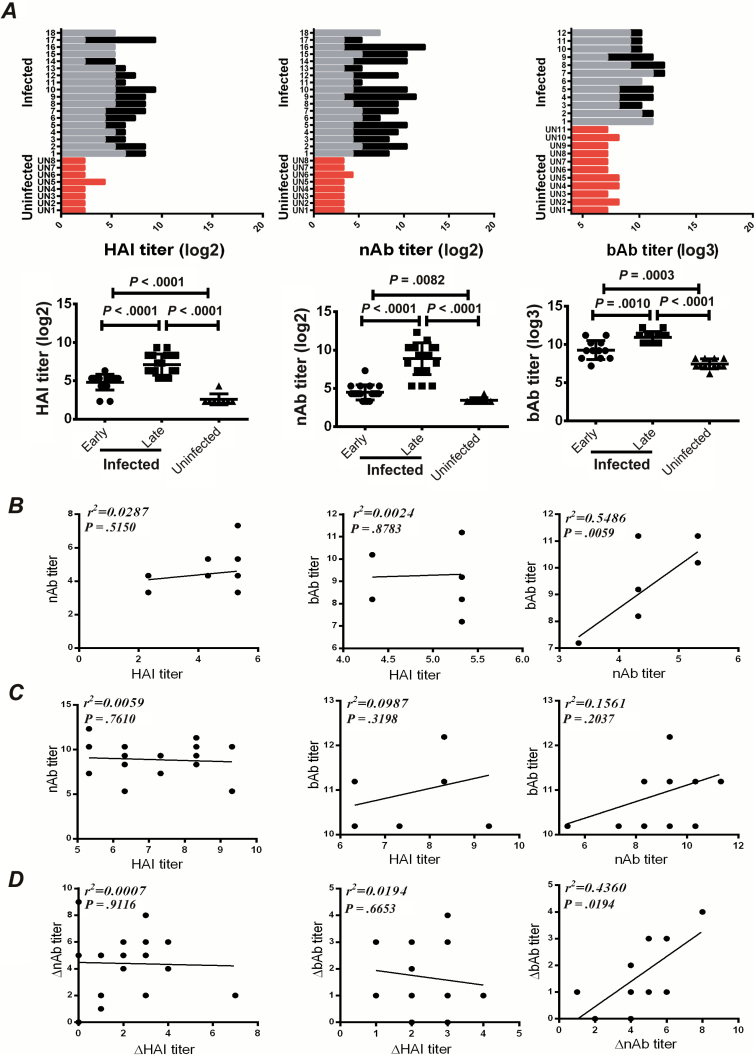

To evaluate the induction of H7N9-specific antibody in H7N9-infected patients, we tested the HAI and nAb responses against homologous SH13 H7 virus of the sera using live virus (HAI) and pseudovirus-based neutralization assays [21]. Binding antibody titers (bAb) were tested by ELISAs using recombinant SH13 H7 HA protein as substrate. The results showed that all patients experienced robust induction of SH13 H7N9-specific antibodies at the late stage of infection, generating significantly higher values than those observed at the early infection stage (Figure 1A). In contrast, only marginal HAI, nAb, and bAb antibodies were detected in uninfected subjects (Figure 1A). Taken together, these data confirmed that H7N9 is highly immunogenic and capable of eliciting vigorous humoral responses in humans. We next determined the dynamics of nAb responses in 6 representative patients with prolonged hospitalization. All 6 patients exhibited a rapid increase in nAb responses within 20 days after disease onset, peaking at 20–40 days (Supplementary Figure 1A). Interestingly, the neutralization activities were closely associated with binding antibody titers the early infection stage (Figure 1B and 1D). However, no correlation between HAI titers and nAb or bAb titers was observed (Figure 1B−D). Indeed, a previous study identified a number of non-HAI but neutralizing monoclonal antibodies from H7 vaccinated subjects [23].

Figure 1.

Antibody responses against homologous 2013 H7 virus in H7N9-infected patients. A, Serum samples from H7N9-infected patients were collected at the early (gray; sampled within 1–2 days after admission) or late (dark) (Table 1) stages of infection, hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers (log2) were tested using live virus-based HAI assays (left), neutralizing antibodies (nAb) titers (log2) were tested by pseudovirus-based neutralization assays (middle), and binding antibody (bAb) titers (log3) were tested by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant protein SH13 H7 HA as substrate (right). Age-matched uninfected people were used as controls (red). A comparison of the antibody responses (log2) between the early and late stages of H7N9 infection or in uninfected subjects were performed using paired or unpaired t tests, respectively. B, Correlation between the HAI, bAb, and nAb titers in serum samples collected at early infection stage. C, Correlation between the HAI, bAb, and nAb titers in serum samples collected at the late infection stage. D, Correlation between the induction levels (late, early) of HAI, bAb, and nAb titers in serum samples.

To rule out the interference of residual oseltamivir in the sera, which was administered during treatment, we examined the inhibitory effect of the sera from uninfected subjects containing different concentrations of oseltamivir. The results showed that even at a high concentration, oseltamivir failed to reach an IC80, defined as neutralizing positive in our pseudotyped virus-based neutralization assays (Supplementary Figure 1B). Furthermore, we observed that the serum-neutralizing activities were significantly reduced after IgG depletion (Supplementary Figure 1C). These data demonstrate that neutralization activities are primarily mediated by induced IgG and closely correlated with the bAb titers.

Heterologous H7 Antibody Responses in H7N9-Infected Patients

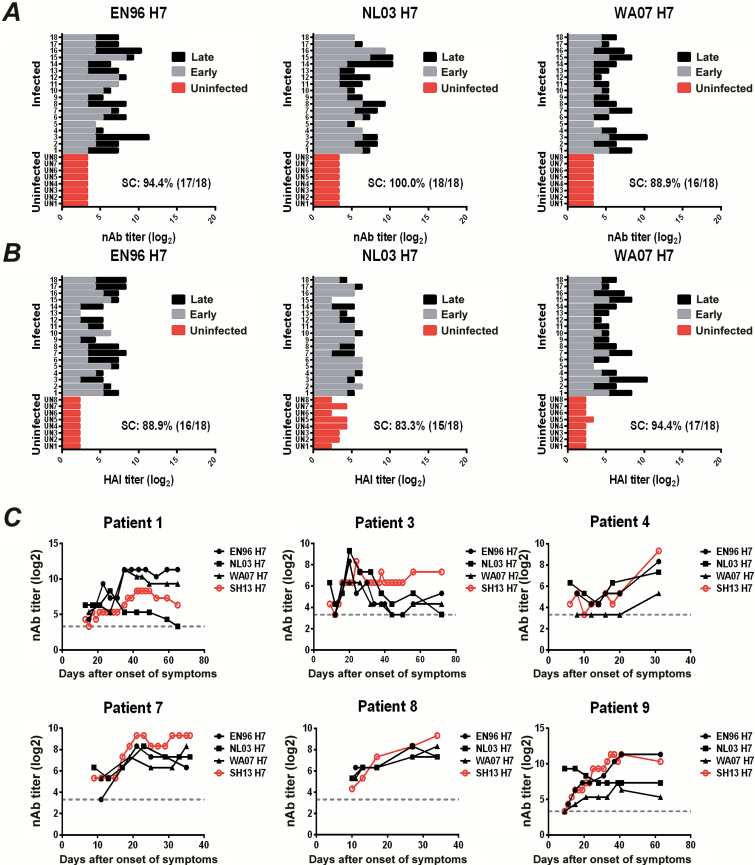

To determine cross-reactive immunogenicity against other H7 strains, we tested serum antibody activities against 3 other heterologous H7-pseudotyped viruses (EN96 H7, NL03 H7, and WA07 H7) (Supplementary Table 2). As shown in Figure 2A, high levels of nAb against all 3 heterologous H7 viruses were elicited at the late infection stage, with values significantly higher than those observed at the early infection stage (Supplementary Figure 2A). Similarly, high levels of HAI antibody responses against these H7 viruses were observed at the late infection stage (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 2B). In contrast, all uninfected subjects showed marginal antibody responses against these H7 viruses in both HAI and nAb assays (Figure 2A and 2B). We further analyzed the dynamics of nAb responses in 6 representative patients, and the results showed that the nAb responses to these heterologous H7 viruses were similar to the responses elicited against SH13 H7 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Intrasubtypic antibody responses against heterologous H7 viruses in H7N9 infected patients. A, Neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers (log2) against EN96 H7 (left), NL03 H7 (middle), or WA07 H7 (right) pseudoviruses. B, Hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) titers (log2) against EN96 H7 (left), NL03 H7 (middle), or WA07 H7 (right) pseudoviruses. Serum samples from 18 H7N9-infected patients were collected at the early (gray) or late (dark) stages of infection as indicated above, and nAb or HAI titers were quantified using pseudovirus-based neutralization or HAI assays. Sera from 8 uninfected patients (red) were used as controls. The rate of seroconversion (SC) of HAI or nAb against pseudotyped viruses was defined as titers ≥40 or 4-fold increases. C, Dynamic nAb titers (log2) against EN96 H7 (●), NL03 H7 (■), or WA07 H7 (▲) were quantified in patients 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 9 using a pseudovirus-based assay. Dynamic nAb titers (log2) against homologous H7 virus SH13 H7 (red ○) were used as reference. The gray dashed line represents the geometric mean of the uninfected controls.

Broadly Reactive Polyclonal Humoral Responses Against Both Group 1 and Group 2 Influenza Hemagglutinin induced by H7N9 infection

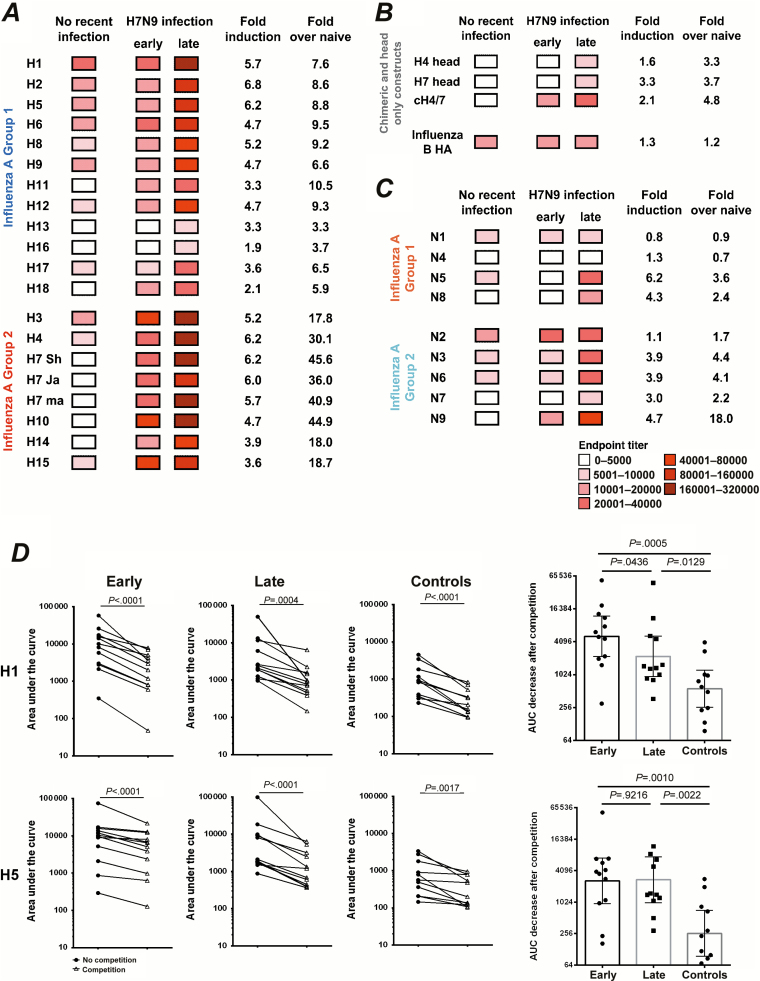

We next evaluated whether the antibodies elicited by H7N9 infection could react to other influenza HAs and NAs, and then by using chimeric HAs (cHAs) and HA head-only constructs we tested against which HA domain—head or stalk—these antibodies mainly react [24]. Sera were tested for endpoint titers by ELISA that used recombinant influenza HA and NA proteins as substrate (Supplementary Table 1), and the geometric means of antibody titers were used to create a heatmap (Figure 3). Because H7N9 virus is novel to humans, the serum antibody titers against cognate H7 and heterologous H7 HAs in uninfected individuals were low at baseline (Figure 3A). Because most of the infected patients and uninfected controls were primed for seasonal influenza virus, as data in Figure 3A show, antibodies against H1 (group 1) and H3 (group 2) are already high in uninfected controls. There is a similar tendency in anti-NA antibodies, as anti-N1 antibodies are the highest for group 1 NAs and anti-N2 antibodies are the highest in group 2 NAs (Figure 3C). These data indicate that prior infections or vaccination imprinted the immune system and induced preexisting immunity. Although H4 and H5 influenza strains are relatively exotic for humans, interestingly, anti-H4 and anti-H5 HA antibodies were also found in uninfected controls (Figure 3A) This low reactivity is most likely mediated by cross-reactive anti-stalk antibodies induced by H1N1 and H3N2 infection, which usually increase with age [10, 16, 19].

Figure 3.

H7N9 infection induced broadly reactive humoral responses against both group 1 and group 2 influenza viruses. A, Heatmap analysis of antibody titers against influenza group 1 and group 2 recombinant hemagglutinins. Serum samples from uninfected age-matched controls (with no recent infection, n = 11) and H7N9-infected patients (early and late stage after disease onset, n = 12) were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). The geometric mean titers were used to create the heatmaps. Fold induction of late versus early time points or versus naive uninfected controls are calculated based on the geometric mean titers. B, The same set of serum samples was analyzed for HA stalk and head reactivity by chimeric or head-only constructs; influenza B HA (B/Yamagata/16/1988) was also included. The chimeric HAs were constructed with the head domain of an H4 virus and the stalk domain of an H7 strain (cH4/7). C, The same set of serum samples was analyzed for reactivity against influenza group 1 and group 2 recombinant neuraminidase proteins. D, Left: Competition ELISA assays for H1 and H5 with a monoclonal group 1 stalk-specific antibody (GG3). Area under the curve was used for antibody reactivity with or without monoclonal antibody (mAb) competition. Right: Area under the curve was calculated to indicate the antibody reactivity reduction after mAb (GG3) competition. All 12 surviving H7N9-infected patients and 11 uninfected age-matched individuals were tested.

After H7N9 infection, robust anti-H7 HA-specific antibodies were induced against homologous H7 HA and heterologous H7 HAs (Figure 3A). Besides H7 HA, induction of antibodies that react with other HAs in influenza group 2 was also robust, even at the early time point (Figure 3A). Interestingly, antibodies reactive to group 1 HAs increased 3–10-fold in patients at late stage after H7N9 infection compared with uninfected controls. Indeed, antibodies reacting with H6, H8, H11, H12, and H18 were already increased at the early time point after H7N9 infection in case patients compared with healthy individuals. The overall induction of antibodies against influenza group 1 HAs were lower than against group 2 HAs (Figure 3A). However, no induction of antibodies against influenza B HA—which shares little conservation with influenza A HA—was detected (Figure 3B), the induction of antibodies against NA was much lower than for HA, and the induced antibodies mainly reacted with group 2 influenza NAs (Figure 3C). Overall, broadly cross-reactive antibodies were elicited even at the early stage of infection and primarily target HA but not NA proteins.

To further prove that H7 HA shares conserved antibody epitopes with other HAs, 4 sera from H7N9 infected patients were absorbed with H7 HA proteins, and then determined binding activities of sera before and after absorption against H3, H5, H6, and H7 HAs. As expected, the absorption of sera with H7 HA resulted in >80% reduction of binding activities against H7 HA, approximately 50% reduction for H3 and H6 HA, and a less than 40% reduction for H5 HA (Supplementary Figure 3A). These data indicated that H7 HA does share conserved epitopes with both group 1 and 2 HAs, and the shared fraction decreases with phylogenetic distances to H7. We next investigated which part of HA was targeted by these cross-reactive antibodies by measuring for HA stalk and head reactivity using chimeric or head-only constructs. The chimeric HA was constructed with the head domain of H4 and the stalk domain of H7 (cH4/7). As shown in Figure 3B, antibodies against the H4 head and against the H7 head were only elicited at the late time point after H7N9 infection; however, that was not the case with antibodies against cH4/7, which were elicited early after H7N9 infection (Figure 3B). This indicates that antibodies reacting with the H7 stalk region were induced early after infection, whereas antibodies against H7 head and other HA heads in group 2 influenza were induced later.

To confirm that cross-group responses were mediated by an increase in stalk-specific antibodies, we performed competition ELISAs for H1 and H5 with a mouse monoclonal group 1 stalk-specific antibody, GG3. The binding activities before and after competition were calculated as area under the curve, and the GG3-mediated inhibition was shown as the shadow area between 2 curves (Supplementary Figure 3B). Importantly, preincubation of H1 and H5 HA with GG3 resulted in significant decreases in bAb titers for all sera from both H7N9-infected and -uninfected subjects (Figure 3D, left), and significant stronger inhibitions were observed for sera collected from both the early and late stage of H7N9 infection in comparison with that observed in the control group (Figure 3D, right). Interestingly, the GG3-mediated inhibition peaked at the early stage, and no further increase was observed at the late stage of infection (Figure 3D, right), indicating the GG3 epitope mainly induced memory responses.

Cross-Neutralizing and Hemagglutination Inhibition Antibody Responses to Heterosubtypic Influenza Viruses

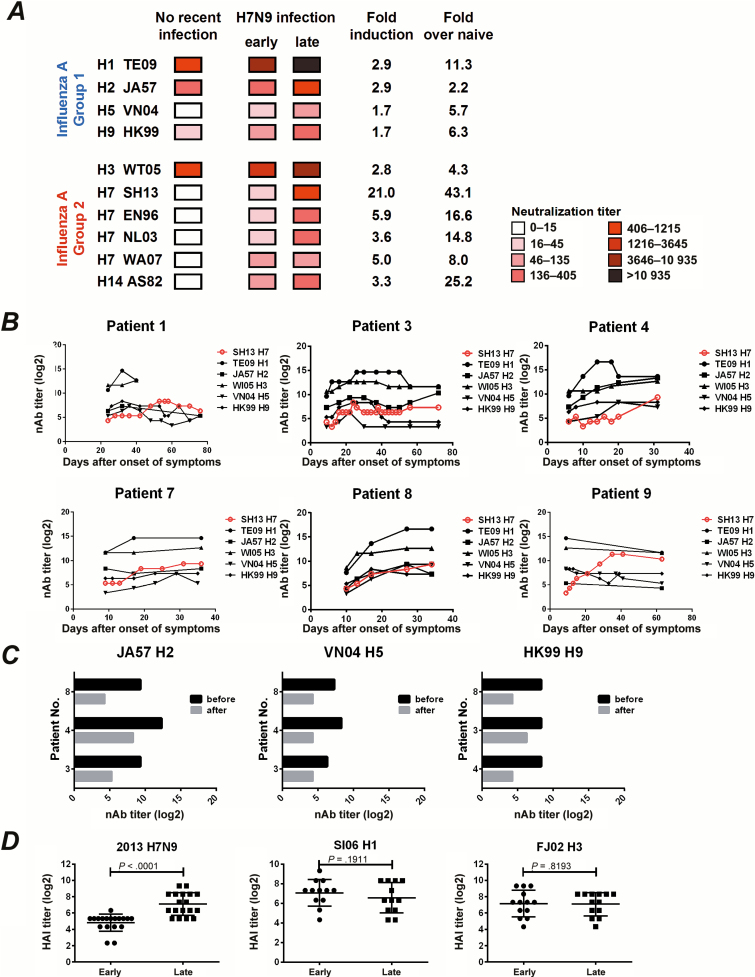

Because our ELISA data suggested that H7N9 infection induced broadly reactive polyclonal humoral responses against both group 1 and group 2 HAs and H7N9-specific nAb correlate well with bAb, we inferred that this novel H7N9 infection might also induce cross-subtype nAb responses. We evaluated nAb responses against different pseudotyped viruses in all 18 patients (Supplementary Table 2) and used GMT data to create a heatmap (Figure 4A). Several important observations were noted. First, substantial titers of nAbs against H1, H2, and H3 influenza were detected in uninfected controls (Figure 4A and Supplementary Table 3). Second, at the early infection stage, most of the sera showed increased titers of nAbs against heterosubtypic influenza viruses, except for H2 virus (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 4A). Third, at the late infection stage, nAb titers against all group 2 influenza viruses showed a robust increase, whereas the induction was much lower in group 1 influenza virus, except for H1 virus (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 4A). Interestingly, more nAb activities were observed against heterosubtypic H1, H3, H9, H14, and WA07 H7 than against homologous SH13 H7 during the early infection (Figure 4A), and we inferred that cross-reactive memory B cells were raised at the early stage of H7N9 infection in the same pattern as bAbs. Importantly, significant correlation of nAb with bAb was also observed for H1, H2, and H5 (Supplementary Figure 4B). To determine the dynamics of heterosubtypic nAb responses during H7N9 infection, we monitored the neutralization activities in sera from 6 patients who were hospitalized for a prolonged period. As shown in Figure 4B, cross-subtype nAb responses were synchronized with the response to the homologous SH13 H7 virus in most individuals. Interestingly, we observed that peaks of heterosubtypic nAb responses appeared earlier than peaks for homologous nAb responses against SH13 H7 in patients 1, 3, 4, and 9. To determine whether the heterosubtypic neutralization was mediated through serum antibodies, we depleted IgG from the late-stage serum samples of 3 patients using Protein A/G and observed a substantial decrease in nAb titers against JA57 H2, VN04 H5, and HK99 H9 subtypes, respectively (Figure 4C). Overall, the cross-reactive nAbs against heterosubtypic HA are likely to be mediated by cross-reactive memory responses.

Figure 4.

Neutralizing antibody (nAb) and hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) antibody responses against heterosubtypic influenza virus in H7N9-infected patients. A, Heatmap analysis of nAb responses against H1, H2, H3, and H5 strains of group 1 influenza and H3, H7, and H9 strains of group 2 influenza (Supplementary Table 2). Serum samples from 8 uninfected age-matched controls and 18 H7N9-infected patients collected at the early and late stages of infection were quantified for nAb titers using a pseudovirus-based neutralization assay. The geometric means of nAb titers were used to create the heatmap. Fold induction of late versus early time point or versus naive uninfected controls were calculated based on the geometric mean of nAb titers. B, Dynamics of cross-subtype nAb responses (log2) in 6 selected patients. The nAb titers (log2) against TE09 H1 (●), WI05 H3 (▲), JA57 H2 (■), VN04 H5 (▼), and HK99 H9 (◆) pseudotyped viruses were quantified in the serum samples obtained from patients at different time points after disease onset. The nAb titers (log2) against SH13 H7 (red ○) were used as controls for strain-specific nAb responses. C, Decreases in cross-subtype nAb responses after immunoglobulin G (IgG) depletion. Serum samples obtained from the indicated patients at the late infection stage were treated with Protein A/G, and the nAb titers were assessed against JA57 H2 (left), VN04 H5 (middle), or HK99 H9 (right) pseudotyped viruses. The dark and gray bars represent the nAb titers (log2) before and after IgG depletion, respectively. D, Comparison in HAI responses (log2) against SI06 H1 (middle) or FJ02 H3 (right) between early and late stage of H7N9 infection. HAI titers (log2) against 2013 H7N9 virus were used as controls for strain-specific responses. A paired t test was used to calculate the P value.

To assess the breadth of the nAbs in patients 3, 4, and 8, we further evaluated the nAb activities against an additional panel of pseudotyped viruses, including H8, H10, H13, H15, influenza type B, 4 additional H1 viruses, and 3 H3 viruses (Table 2). The results showed that patient 4 raised the broadest spectrum of neutralizing responses, including H1, H2, H3, H5, H8, H9, H11, H14, and H15, and patients 3 and 8 exhibited a less cross-reactive breadth of nAb responses (Table 2). In contrast, no significant HAI antibodies were induced against all heterosubtypic HAs in all three patients at both the early and late infection stages; this also holds true against H1 and H3 in all 18 patients (Figure 4D), whereas nAbs were significantly increased during H7N9 infection. These data suggest that cross-reactive heterosubtypic nAbs are primarily elicited to the stalk but not the head region.

Table 2.

The Breadth of Neutralizing Antibody or Hemagglutination Inhibition in Serum of H7N9 Patients

| Virus | Typea | Patient 4 | Patient 3 | Patient 8 | Uninfected Subjects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Late | SCb | Early | Late | SC | Early | Late | SC | |||

| SC18 H1 | nAb | 1600 | 1600 | − | 1600 | 1600 | − | 800 | 1600 | − | 229.7 (74.8–705.5)c |

| SI86 H1 | nAb | 3200 | 12800 | + | 12800 | 3200 | − | 1600 | 1600 | − | 1838 (894.6–3776) |

| NC99 H1 | nAb | 12800 | 12800 | − | 12800 | 12800 | − | 12800 | 12800 | − | 7352 (2394–22576) |

| SI06 H1 | nAb | 1600 | 1600 | − | 1600 | 3200 | − | 1600 | 3200 | − | 4222 (1145–15572) |

| HAI | 160 | 320 | − | 320 | 320 | − | 160 | 320 | − | 20.0 (10.9–36.8) | |

| TE09 H1 | nAb | 800 | 25600 | + | 800 | 25600 | + | 200 | 102400 | + | 1077 (476.3–2434) |

| JA57 H2 | nAb | 160 | 10240 | + | 160 | 1280 | + | 20 | 160 | + | 202 (67.4–602) |

| MO99 H3 | nAb | 1600 | 6400 | + | 1600 | 12800 | + | 1600 | 6400 | + | 2425 (508.0–11578) |

| FJ02 H3 | nAb | 3200 | 12800 | + | 3200 | 12800 | + | 3200 | 12800 | + | 3676 (1789–7551) |

| HAI | 160 | 320 | − | 160 | 320 | − | 160 | 160 | − | 183.8 (59.9–564.4) | |

| WI05 H3 | nAb | 1600 | 6400 | + | 1600 | 25600 | + | 400 | 25600 | + | 1449 (309–6765) |

| VN04 H5 | nAb | 20 | 320 | + | 10 | 80 | + | 10 | 640 | + | 10.9 (8.89–13.39) |

| AL79 H8 | nAb | 40 | 160 | + | 20 | < 20 | − | 40 | 80 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) |

| HAI | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | 10.9 (8.89–13.39) | |

| HK99 H9 | nAb | 80 | 320 | + | 40 | 320 | + | 40 | 320 | + | 20.0 (12.90–31.00) |

| HAI | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) | |

| YZ02 H11 | nAb | 80 | 40 | − | 80 | < 20 | − | 80 | < 40 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) |

| ALB91 H12 | nAb | 20 | < 40 | − | 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 40 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) |

| HAI | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) | |

| AS82 H14 | nAb | 80 | 640 | + | 40 | 40 | - | 80 | 80 | − | 10.9 (8.89–13.39) |

| HAI | < 20 | < 20 | − | < 20 | < 20 | - | < 20 | < 20 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) | |

| AUS83 H15 | nAb | 160 | 40 | − | 160 | 40 | - | 80 | 40 | − | 10.0 (10.00-10.00) |

| BR08 BHA | nAb | 800 | 200 | − | 800 | 1600 | - | 800 | 400 | − | 303.1 (189.2–485.7) |

| HAI | 160 | 320 | − | 80 | < 20 | - | 160 | 320 | − | 211.1 (79.2–563.2) | |

| FI06 BHA | nAb | 12800 | 3200 | − | 12800 | 12800 | - | 12800 | 6400 | − | 6400 (1642–24951) |

Abbreviations: HAI, hemagglutination inhibition; nAb, neutralizing antibody; SC, seroconversion.

aNeutralizing antibody (80% inhibitory concentration) or HAI titers against a panel of pseudovirus (Supplementary Table 1) or live virus in serum sample from H7N9-infected patient 4, 3, or 8.

bDefined as ≥4-fold increases in nAb or HAI titers at late stage compared with that at early stage during infection.

cGeometric mean titers (95% confidence interval) of nAb or HAI in 4–8 age-matched uninfected people (Supplementary Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Given the constant drift of seasonal influenza virus and the threat from potential pandemic viruses like H7N9, an increasing number of studies have focused on inducing a new class of antibodies that bind to the HA stalk domain [25–28]. It has been shown that individuals infected with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus experienced a boost in HA stalk-reactive antibodies that may be responsible for the extinction of the previous seasonal H1N1 virus [12, 29]. However, H3N2 infection only stimulates modest polyclonal antibody responses directed against the conserved stalk region of group 2 HA proteins [16]. Our study represents the first comprehensive analysis of cross-reactive antibody responses induced by natural infection of humans with the novel H7N9 virus, showing that cross-group reactive stalk antibody responses can be boosted. We found substantial induction of homotypic, heterosubtypic, and cross-group reactive antibody responses in our H7N9 cohort, both at early and late stages. The homotypic H7 immune response was observed relatively late in infection and led to an increase in neutralizing, binding, and HAI active antibodies. This response was strongest against the homologous strain, and good induction of nAbs and bAbs against heterologous H7 strains was observed as well, confirming earlier reports from preclinical and clinical H7 vaccine studies that suggested broad cross-reactivity within H7 [30–34]. Interestingly, we also found strong heterosubtypic antibody responses after natural infection with H7N9 virus. These responses were primarily directed towards the stalk domain as shown by the absence of HAI (or increase thereof) against the tested strains, and stalk/stalk competition ELISAs. These responses were induced early during infection, indicating a recall response of preexisting immunity. Of note, this response was also exceptionally broad, crossing from group 2 to group 1 HAs and to a larger extent as seen with H7 vaccination [30, 31]. Importantly, this broad response was sufficient to neutralize viral infection.

An important caveat of our data set is that it was not possible to obtain preinfection sera from the H7N9-infected individuals. H7N9-infected individuals might have had a different pre-exposure history than the noninfected age-matched controls, including possible exposure to avian influenza virus strains circulating in poultry and waterfowl. Such an exposure could have led to a different preexisting immunity in the cases than in the controls and could have skewed their antibody response to H7N9, especially at earlier time points. However, the pattern of antibody induction of infected individuals between early and late time points mostly reflects the antibody induction of infected individuals over control individuals, suggesting that there are few or no confounding effects.

The majority of infected individuals tested in this study were aged >60 years. Because influenza viruses constantly circulate in the human population, it is very likely that all individuals have been repeatedly exposed to seasonal influenza viruses (including other group 2 viruses). The breadth of the observed responses is most likely based in part on recall responses of memory B cells with specificities for epitopes conserved between seasonal influenza viruses and H7N9. It is likely that the responses would be narrower in naive individuals (e.g., children) in the absence of previous priming.

In conclusion, memory B cells that target conserved epitopes of the HA seem to get activated first, whereas B cells that target more specific epitopes take longer to mature and to dominate the response—a phenomenon that has been previously described for infections with the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus [13, 35]. A sequential vaccination strategy using heterologous HAs or cHAs could likely induce similar responses by specifically presenting conserved epitopes in combination with novel head domains. These vaccinations could elicit broadly cross-reactive antibody responses that might universally protect against influenza viruses.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank all study participants for their donation of blood samples, and Miaomiao Zhang for her help in HAI testing.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China [8161101262, 81470094, 81430030], Shanghai ShenKang Hospital Development Center [SHDC12014104] and by the US National Institutes of Health (R01 AI128821).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Gao R, Cao B, Hu Y, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza a (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1888–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watanabe T, Kiso M, Fukuyama S, et al. Characterization of H7N9 influenza a viruses isolated from humans. Nature 2013; 501:551–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Skowronski DM, Chambers C, Gustafson R, et al. Avian influenza a (H7N9) virus infection in 2 travelers returning from China to Canada, January 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:71–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lam TT, Zhou B, Wang J, et al. Dissemination, divergence and establishment of H7N9 influenza viruses in China. Nature 2015; 522:102–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koopmans M, Wilbrink B, Conyn M, et al. Transmission of H7N7 avian influenza a virus to human beings during a large outbreak in commercial poultry farms in the Netherlands. Lancet 2004; 363:587–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Editorial team. Avian influenza A/(H7N2) outbreak in the United Kingdom. Euro Surveill 2007;12:E70531-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirst M, Astell CR, Griffith M, et al. Novel avian influenza H7N3 strain outbreak, British Columbia. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:2192–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Skowronski DM, Li Y, Tweed SA, et al. Protective measures and human antibody response during an avian influenza H7N3 outbreak in poultry in British Columbia, Canada. CMAJ 2007; 176:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meijer A, Bosman A, van de Kamp EE, Wilbrink B, Du Ry van Beest Holle M, Koopmans M. Measurement of antibodies to avian influenza virus A(H7N7) in humans by hemagglutination inhibition test. J Virol Methods 2006; 132:113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miller MS, Tsibane T, Krammer F, et al. 1976 and 2009 H1N1 influenza virus vaccines boost anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans. J Infect Dis 2012;207:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Qiu C, Huang Y, Wang Q, et al. Boosting heterosubtypic neutralization antibodies in recipients of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis 2011;54:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pica N, Hai R, Krammer F, et al. Hemagglutinin stalk antibodies elicited by the 2009 pandemic influenza virus as a mechanism for the extinction of seasonal H1N1 viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:2573–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krammer F, Palese P. Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines. Curr Opin Virol 2013; 3:521–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krammer F, Pica N, Hai R, Margine I, Palese P. Chimeric hemagglutinin influenza virus vaccine constructs elicit broadly protective stalk-specific antibodies. J Virol 2013; 87:6542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nachbagauer R, Wohlbold TJ, Hirsh A, et al. Induction of broadly reactive anti-hemagglutinin stalk antibodies by an H5N1 vaccine in Humans. J Virol 2014; 88:13260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Margine I, Hai R, Albrecht RA, et al. H3N2 influenza virus infection induces broadly reactive hemagglutinin stalk antibodies in humans and mice. J Virol 2013; 87:4728–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Margine I, Palese P, Krammer F. Expression of functional recombinant hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins from the novel H7N9 influenza virus using the baculovirus expression system. J Vis Exp 2013(81); e51112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krammer F, Margine I, Tan GS, Pica N, Krause JC, Palese P. A carboxy-terminal trimerization domain stabilizes conformational epitopes on the stalk domain of soluble recombinant hemagglutinin substrates. PLoS One 2012; 7:e43603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nachbagauer R, Choi A, Izikson R, Cox MM, Palese P, Krammer F. Age dependence and isotype specificity of influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-reactive antibodies in Humans. MBIO 2016; 7:e1915-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heaton NS, Leyva-Grado VH, Tan GS, Eggink D, Hai R, Palese P. In vivo bioluminescent imaging of influenza a virus infection and characterization of novel cross-protective monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 2013; 87:8272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qiu C, Huang Y, Zhang A, et al. Safe pseudovirus-based assay for neutralization antibodies against influenza a(H7N9) virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19(10):1685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whittle JR, Wheatley AK, Wu L, et al. Flow cytometry reveals that H5N1 vaccination elicits cross-reactive stem-directed antibodies from multiple Ig heavy-chain lineages. J Virol 2014; 88:4047–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henry Dunand CJ, Leon PE, Huang M, et al. Both neutralizing and non-neutralizing human H7N9 influenza vaccine-induced monoclonal antibodies confer protection. Cell Host Microbe 2016; 19:800–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hai R, Krammer F, Tan GS, et al. Influenza viruses expressing chimeric hemagglutinins: globular head and stalk domains derived from different subtypes. J Virol 2012; 86:5774–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okuno Y, Isegawa Y, Sasao F, Ueda S. A common neutralizing epitope conserved between the hemagglutinins of influenza a virus H1 and H2 strains. J Virol 1993; 67:2552–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tan GS, Krammer F, Eggink D, Kongchanagul A, Moran TM, Palese P. A pan-H1 anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibody with potent broad-spectrum efficacy in vivo. J Virol 2012; 86:6179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ekiert DC, Friesen RH, Bhabha G, et al. A highly conserved neutralizing epitope on group 2 influenza A viruses. Science 2011; 333:843–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Corti D, Voss J, Gamblin SJ, et al. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza A hemagglutinins. Science 2011; 333:850–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, et al. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J Exp Med 2011; 208:181–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krammer F, Jul-Larsen A, Margine I, et al. An H7N1 influenza virus vaccine induces broadly reactive antibody responses against H7N9 in humans. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014; 21:1153–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thornburg NJ, Zhang H, Bangaru S, et al. H7N9 influenza virus neutralizing antibodies that possess few somatic mutations. J Clin Invest 2016; 126:1482–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith GE, Flyer DC, Raghunandan R, et al. Development of influenza H7N9 virus like particle (VLP) vaccine: homologous A/Anhui/1/2013 (H7N9) protection and heterologous A/chicken/Jalisco/CPA1/2012 (H7N3) cross-protection in vaccinated mice challenged with H7N9 virus. Vaccine 2013; 31:4305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Klausberger M, Wilde M, Palmberger D, et al. One-shot vaccination with an insect cell-derived low-dose influenza a H7 virus-like particle preparation protects mice against H7N9 challenge. Vaccine 2014; 32:355–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mallett CP, Beaulieu E, Joly MH, et al. AS03-adjuvanted H7N1 detergent-split virion vaccine is highly immunogenic in unprimed mice and induces cross-reactive antibodies to emerged H7N9 and additional H7 subtypes. Vaccine 2015; 33:3784–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andrews SF, Huang Y, Kaur K, et al. Immune history profoundly affects broadly protective B cell responses to influenza. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:316ra192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.