Bundle-sheath leakiness of a perennial C4 grass responds dynamically to short-term variation of atmospheric CO2 concentration, and is altered by long-term changes of vapour pressure deficit.

Keywords: C4 photosynthesis, CO2-concentrating mechanism, carbon isotope discrimination, gas exchange, nitrogen nutrition, vapour pressure deficit

Abstract

Bundle-sheath leakiness (ϕ) is a key parameter of the CO2-concentrating mechanism of C4 photosynthesis and is related to leaf-level intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi). This work studied short-term dynamic responses of ϕ to alterations of atmospheric CO2 concentration in Cleistogenes squarrosa, a perennial grass, grown at high (1.6 kPa) or low (0.6 kPa) vapour pressure deficit (VPD) combined with high or low N supply in controlled environment experiments. ϕ was determined by concurrent measurements of photosynthetic gas exchange and on-line carbon isotope discrimination, using a new protocol. Growth at high VPD led to an increase of ϕ by 0.13 and a concurrent increase of WUEi by 14%, with similar effects at both N levels. ϕ responded dynamically to intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), increasing with Ci. Across treatments, ϕ was negatively correlated to the ratio of CO2 saturated assimilation rate to carboxylation efficiency (a proxy of the relative activities of Rubisco and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase) indicating that the long-term environmental effect on ϕ was related to the balance between C3 and C4 cycles. Our study revealed considerable dynamic and long-term variation in ϕ of C. squarrosa, suggesting that ϕ should be determined when carbon isotope discrimination is used to assess WUEi. Also, the data indicate a trade-off between WUEi and energetic efficiency in C. squarrosa.

Introduction

The CO2 concentrating mechanism (CCM) is a specialized feature of C4 photosynthesis and enables the maintenance of a very high CO2 partial pressure at the site of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), thus effectively minimizing photorespiration (Hatch, 1987). The CCM underlies the higher quantum yield, and higher water- and nitrogen-use efficiency of C4 plants relative to C3 plants under high temperature and/or low intercellular CO2 (Ehleringer et al., 1997; Long, 1999). In C4 photosynthesis, CO2 is first fixed by phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPc) in mesophyll cells to form C4 acids (the C4 cycle), which are transported into bundle-sheath cells, where the acids are decarboxylated and CO2 is finally fixed by Rubisco (the C3 cycle). Effective CCM requires a strong ‘CO2 pump’ (a high rate of the C4 cycle). However, leakage of CO2 from bundle-sheath cells back to mesophyll cells represents an energetic inefficiency that is related to the cost of the regeneration of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP; Hatch, 1987; Furbank et al., 1990). The ratio of this leakage rate to the C4 cycle rate is termed bundle-sheath leakiness (Farquhar, 1983), or leakiness (ϕ), and is a key parameter of C4 photosynthesis.

Leakiness is generally quantified using a carbon isotope approach based on the model of carbon isotope discrimination (Δ) of C4 photosynthesis (Farquhar, 1983). The simplified version of the C4 discrimination model indicates that Δ is determined by ϕ and Ci/Ca, the ratio of intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) to atmospheric CO2 concentration (Ca):

| (1) |

with a the fractionation during diffusion of CO2 in air, b4 the combined fractionation of PEP carboxylation and the preceding fractionation associated with dissolution of CO2 and conversion to HCO3−, b3 the fractionation by Rubisco and s the fractionation during leakage of inorganic C out of the bundle sheath. Since leaf-level intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi; net CO2 assimilation rate/stomatal conductance) is a function of Ci and Ca, combined with Eqn 1 we have:

| (2) |

showing that WUEi can be estimated from Δ if ϕ is known. Similar to the application of Δ to quantify WUEi of C3 plants (Farquhar and Richards, 1984; Yang et al., 2016b), Δ was suggested as a potentially promising screening tool for breeding and improvement of C4 crops (Henderson et al., 1998; Gresset et al., 2014; von Caemmerer et al., 2014). However, such endeavours require knowledge of the magnitude and variability of ϕ and relevant environmental drivers. Early studies led to the notion that leakiness is relatively constant within a species with moderate short-term environmental variation, e.g. in response to light, CO2, and temperature (Henderson et al., 1992). A constant leakiness would largely simplify the relationship between WUEi and Δ. However, more recent studies suggest dynamic variation of leakiness in response to short-term variation of irradiation (Kromdijk et al., 2010; Pengelly et al., 2010; Ubierna et al., 2013; Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014) or temperature (von Caemmerer et al., 2014).

Analysis of dynamic changes of leakiness in response to short-term variation of atmospheric CO2 provides an opportunity for studying the functioning of the CCM. However, model analyses suggested an increase of leakiness with increasing Ci (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Kiirats et al., 2002; Ghannoum, 2009; Yin et al., 2011), while (the few) experimental studies using the carbon isotope approach showed no clear response of leakiness to Ci (Henderson et al., 1992; Pengelly et al., 2012).

Long-term effects of environmental drivers on leakiness have been observed. Thus, drought stress was shown to increase leakiness of several species (Saliendra et al., 1996; Williams et al., 2001; Fravolini et al., 2002), and this effect was attributed to the relative activities of Rubisco/PEPc (Saliendra et al., 1996). N stress was reported to affect leakiness of several sugarcane species (Meinzer and Zhu, 1998), but another study with different species found no effect of N fertilizer supply (Fravolini et al., 2002). Increased CO2 concentration was shown to increase (Watling et al., 2000; Fravolini et al., 2002) or have no effect (Williams et al., 2001) on leakiness. Currently, it is unknown if vapour pressure deficit (VPD) during plant growth has an effect on leakiness. Studies on long-term effects of N nutrition, water supply, or CO2 concentration during growth on leakiness using biomass-based Δ have considerable uncertainty related to post-photosynthetic fractionation and the temporal mismatch between biomass formation and gas exchange measurements as discussed by many authors (Henderson et al., 1992; Cousins et al., 2008; von Caemmerer et al., 2014).

Scarcity of experimental evidence is partially due to the fact that quantifying leakiness using combined measurements of gas exchange and ∆ (‘on-line’ ∆) is a laborious task. Measurement artefacts, i.e. CO2 leak fluxes between the leaf cuvette and the surrounding air and isotopic disequilibria between photosynthetic and respiratory CO2 fluxes, can lead to errors of measured ∆ of several permil (Gong et al., 2015). This technical issue is particularly relevant for C4 species, as the ∆ of C4 plants is generally much lower than that of C3 plants (Farquhar, 1983).

A previous study in our lab demonstrated that Cleistogenes squarrosa (Trin.) Keng—a perennial C4 (NAD-ME) grass and co-dominant species in the semiarid steppe of Inner Mongolia—had a large and variable biomass-based Δ of leaves (6–9‰; Yang et al., 2011), potentially indicating a high and variable ϕ. As ϕ is related to WUEi (Eqn 2) and potentially driven by environmental factors, we were interested to unravel the mechanisms governing Δ in this C4 species. Furthermore, understanding the physiological response of C. squarrosa to N nutrition and VPD may provide new insight into the adaptation of this species to its habitat given that: (i) water and N availability are the major limiting factors that determine primary production and resource use efficiency of plants in the semiarid steppes of Inner Monglia (Gong et al., 2011) and (ii) the abundance of C4 plants has increased substantially during the past several decades in the Mongolian plateau (Wittmer et al., 2010). Given the lack of knowledge on long-term effects of VPD or N nutrition and short-term dynamic effects of CO2 on ϕ, we performed controlled environment experiments with C. squarrosa grown under a low or high level of VPD combined with a low or high level of N fertilizer supply. Leakiness was determined using combined measurements of gas exchange and ∆ (on-line ∆) following the protocols of Gong et al. (2015).

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Cleistogenes squarrosa is an NAD-ME type (determined by 14C labelling) C4 grass, with a ‘chloridoid’ type of Kranz anatomy (Pyankov et al., 2000). Stands of C. squarrosa were grown from seed in plastic pots (5 cm diameter, 35 cm depth) filled with quartz sand. Pots were placed in growth chambers (PGR15, Conviron, Winnipeg, Canada) at a density of 236 plants m−2. A photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 800 µmol m−2 s−1, provided by cool white fluorescent tubes, was maintained at the top of the canopies during the 16 h-long photoperiods. Air temperature was maintained at 25 ºC during photo- and dark periods. A CO2 concentration ([CO2]) of 386±3 µmol mol−1 (mean±SD, n>400) in chamber air was maintained during the photoperiods (cf. Schnyder et al., 2003). A modified Hoagland nutrient solution was supplied three times per day by an automatic irrigation system throughout the entire experiment similar to Lehmeier et al. (2008). The time of first watering is referred to as imbibition of seeds. Before germination, all chambers were run with a VPD of 0.63 kPa (corresponding to a relative humidity (RH) of 80%).

N nutrition and VPD treatments

The study had a 2 × 2 factorial design, with N fertilizer supply and VPD as factors, two levels (low and high, see below) for each factor, and four replicates (four replicate stands) for each combination of N and VPD level. About 1 week after the imbibition of seeds (i.e. first watering), VPD and N treatment were implemented until the end of the experiment. The nutrient solution with 7.5 mM N in the form of equimolar concentrations of calcium nitrate and potassium nitrate was supplied to chambers of the low N treatment (N1), while another nutrient solution with 22.5 mM N was supplied to chambers of the high N treatment (N2). The concentration of other nutrients was the same in both nutrient solutions: 1.0 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM NaCl, 125 µM Fe-EDTA, 46 µM H3BO3, 9 µM MnSO4, 1 µM ZnSO4, 0.3 µM CuSO4, 0.1 µM Na2MoO4. VPD (difference between actual vapour pressure and the saturation vapour pressure) was maintained at 0.63 kPa (corresponding to an RH of 80%) in the chambers of the low VPD treatment (V1) or at 1.58 kPa (corresponding to an RH of 50%) in the chambers of the high VPD treatment (V2). Each chamber (or each stand) was assigned to one of the treatments: N1V1, N1V2, N2V1, and N2V2. As we had a total of four chambers, in order to repeat each treatment four times, all replicates were accommodated in four sequential experimental runs (in total, 16 stands were grown) (cf. Table S1 in Liu et al. 2016). In each treatment, two replicate chambers were supplied with CO2 from a mineral source (δ 13CCO2 of −6‰) and the other two chambers with CO2 from an organic source (δ 13CCO2 of −33‰). Carbon isotope discrimination by the canopies led to some 13C-enrichment of the CO2 inside the growth chambers. However, that effect was small due to a high rate of air flow through the chambers: quasi-continuous on-line measurements of δ 13CCO2 inside the growth chambers demonstrated a δ 13CCO2 inside the chambers with the 13C-enriched CO2 source of −5.2±0.1‰ (mean±SD, n=23) and −31.7±0.1‰ (n=23) inside the chambers with the 13C-depleted CO2.

Gas exchange measurement system

The method reported by Gong et al. (2015) was used for leaf-level combined measurements of gas exchange and 13C discrimination (on-line ∆). Measurements were performed using a leaf-level 13CO2/12CO2 gas exchange and labelling system, which included a portable CO2 exchange system (LI-6400, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) housed in a gas exchange mesocosm (Gong et al., 2015). The air supply to the mesocosm and LI-6400 was mixed from CO2-free, dry air, and CO2 of know δ13CCO2 (cf. Schnyder et al., 2003). [CO2] inside the mesocosm (growth chamber) was monitored with an infrared gas analyser (LI-6262, LI-COR Inc.). During the measurement, the plant to be measured and the sensor head of the LI-6400 were placed inside the mesocosm, with concentration and δ13C of CO2 in both gas exchange facilities monitored and controlled. Using this set-up, we separately controlled the concentration and δ13C in both facilities (sensor head and growth chamber) for purposes of gas exchange measurement or 13C labelling (see below).

The mesocosm and leaf cuvette systems were coupled to a continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; Deltaplus Advantage equipped with GasBench II, ThermoFinnigan, Bremen, Germany) via a stainless steel capillary. Sample air was drawn through the capillary via a peristaltic pump and passed through a 0.25 ml sample loop attached to the 8-port Valco valve of the GasBench II. Sample air in the loop was introduced into the IRMS via an open split after passage of a dryer (Nafion) and a GC column (25 m×0.32 mm Poraplot Q; Chrompack, Middleburg, The Netherlands). After every second sample a VPDB-gauged CO2 reference gas was injected into the IRMS via the Open Split. The whole-system precision (SD) of repeated measurements was 0.10‰ (n=50). For further details of the method see Gong et al. (2015).

Gas exchange and concurrent on-line 13C discrimination measurements

Gas exchange and on-line ∆ measurements followed the optimized protocols suggested by Gong et al. (2015). In order to minimize the effects of any CO2 leak artefact across the gaskets of the clamp-on leaf cuvette and the surrounding (mesocosm) air, [CO2] inside the mesocosm was maintained close to that of the leaf cuvette of the LI-6400 (with the difference <30 μmol mol−1), and the same CO2 source was supplied to the mesocosm and LI-6400. By these means, the diffusive gradient of 13CO2 or 12CO2 between leaf cuvette and the surrounding air was effectively minimized (Gong et al., 2015). In order to also minimize the isotopic disequilibrium artefact between the photosynthetic and respiratory CO2 flux, the same CO2 source was used for growing plants and for on-line leaf-level ∆ measurements (Gong et al., 2015).

Gas exchange and on-line ∆ measurements were performed on the fully expanded young leaves near the tip of major tillers (the second youngest fully expanded leaf), started at about 38 days and ended at about 53 days after the imbibition of seeds. We used the standard 2 × 3 cm cuvette of LI-6400. Two leaf blades from separate major tillers of the same plant were carefully placed in the cuvette. This was done to compensate for the narrow leaf width of C. squarrosa (about 3 mm). The enclosed leaf area was determined after gas exchange measurements by photographing the leaf blades and analysis with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). All gas exchange parameters were recomputed using the measured enclosed leaf area.

Photosynthetic CO2 response curves were taken with the successive CO2 steps of 390, 800, 390, 260, 180, 120, 90, 60, and 30 μmol mol−1 ([CO2] in the cuvette) on at least two plants randomly chosen from each growth chamber. In total, 42 plants were measured. The data of five plants were eliminated from further analysis due to extremely low leaf N contents. Finally, each treatment had nine to ten replicates of individual plants. During the gas exchange measurements, the environmental parameters were maintained close to the growth conditions: leaf temperature was maintained at 25 °C, PPFD at 800 µmol m−2 s−1, leaf-to-air VPD at 0.76–0.96 kPa (V1 treatment) or 1.4–1.6 kPa (V2 treatment; Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online) at all CO2 levels. To generate the appropriate VPD for gas exchange measurements, the inflow air stream (well-mixed dry air) was passed through a gas washing bottle placed in a temperature-controlled water bath. For each step of the CO2 response, the [CO2] in the mesocosm was also adjusted to be close to that of the cuvette. Leaves were acclimated for at least 30 min before the start of gas exchange measurements. After CO2 exchange rates reached a steady state at each step of the CO2 response, gas exchange parameters (measured by LI-6400), e.g. net CO2 assimilation rate (A), transpiration rate (E), and stomatal conductance to vapour (gs) were recorded. Instantaneous water use efficiency was calculated as WUEins=A/E; intrinsic water use efficiency was calculated as WUEi=A/gs.

Among the 37 CO2 response curves, 22 plants were concurrently measured for on-line 13C discrimination. For this, the [CO2] and δ13C of the incoming (Cin and δin) and outgoing cuvette air (Cout and δout) were measured on five to six plants per treatment combination. All measurements of δ13C were corrected for the non-linearity effect of the IRMS (Elsig and Leuenberger, 2010). 13C discrimination during net CO2 assimilation (∆) was calculated according to Evans et al. (1986):

| (3) |

where ξ=Cin/(Cin−Cout).

Determination of leaf respiration rate in light

Additional measurements were performed to determine leaf respiration rate in light (RL). This was done with leaves of the same age class as used for CO2 response measurements using the 13C labelling method reported by Gong et al. (2015). All measurements were performed under growth conditions (i.e. at Ca of 390 μmol mol−1, PPFD of 800 µmol m−2 s−1). Briefly, ∆ of each leaf was measured first with the same CO2 source as used for growing plants, then the same measurement was repeated with the other CO2 source (i.e. the 13C-enriched or -depleted CO2 source). Making use of isotopic disequilibria between photosynthetic and respiratory CO2 fluxes derived from the two sets of on-line ∆ measurements, the ratio of RL to net CO2 assimilation rate (A) was solved as:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where δA and δout are the δ13C of net CO2 assimilation and that of CO2 in the cuvette, respectively, and subscripts E and D indicate the relevant parameters measured with the 13C-enriched or the 13C-depleted sources of CO2, respectively. RL was measured on six individuals in each treatment. RL of other leaves of the same treatment was estimated by multiplying A of that leaf by the treatment-specific mean of RL/A. For further details of the methodology see Gong et al. (2015).

Bundle-sheath leakiness (ϕ), C3 cycle rate and C4 cycle rate

Bundle-sheath leakiness was determined using the complete version of the Farquhar C4 discrimination model (Farquhar, 1983), modified to include the ternary correction (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012):

| (6) |

where Ca, CL, Ci, Cm, and Cbs are the CO2 concentrations in air (Ca=Cout during gas exchange measurements), at the leaf surface, in the intercellular airspace, in the mesophyll cell, and in the bundle-sheath cell, respectively. CL was calculated as CL=Ca−1.37A/gBL, with gBL the boundary layer conductance to vapour calculated by the LI-6400 software. ab=2.9‰, a=4.4‰, es=1.1‰, al=0.7‰, and s=1.8‰ denote fractionation constants associated with CO2 diffusion across boundary layer, across stomata, dissolution in water, diffusion in liquid phase, and leaking out of bundle sheath cells, respectively. t represents the ternary correction factor (Farquhar and Cernusak, 2012):

| (7) |

where E is the transpiration rate and gsc is the total conductance to CO2: gsc=1/(1.6/gs+1.37/gBL), where gs is the stomatal conductance to vapour. ā is the weighted fractionation across boundary layer (ab=2.9‰) and stomata (a=4.4‰): ā=[ab(Ca−CL)+a(CL−Ci)]/(Ca−Ci). b3 (13C fractionation during carboxylation by Rubisco including respiratory fractionation) and b4 (13C fractionation by CO2 dissolution, hydration, and PEPc carboxylation including respiratory fractionation) were calculated according to Farquhar (1983):

| (8) |

| (9) |

where b′3=30‰, b′4=–5.7‰, e=–6‰ (Ghashghaie et al., 2003; Kromdijk et al., 2010), f=11.6‰ (Ghashghaie et al., 2003; Lanigan et al., 2008), and Vc is the rate of Rubisco carboxylation and Vo is the rate of oxygenation. In our experiments, the same source CO2 was used for growing plants and for online ∆ measurements; therefore an additional term (cf. e′ in Ubierna et al. 2013) accounting for the discrepancy of δ13CCO2 between growth environment and gas exchange measurements was not included. Here, it is assumed that respiration in mesophyll cells (Rm) and bundle-sheath cells (Rbs) both equal 0.5RL (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Pengelly et al., 2010).

To solve ϕ using Eqns 7–9, Cm, Cbs, Vo, and Vc must be estimated. Those parameters were determined using the equations of the C4 photosynthesis model of von Caemmerer and Furbank (1999). Cm can be calculated from:

| (10) |

if mesophyll conductance to CO2 is known. It has been generally assumed that gm is high and non-limiting for CO2 assimilation in C4 photosynthesis. Thus, in many published works on ϕ, gm was assumed to be infinite, i.e. Ci=Cm. However, a recent study using a new oxygen isotope approach found that gm of C4 species ranged between 0.66 and 1.8 mol m−2 s−1 measured at a leaf temperature of about 32 °C (Barbour et al., 2016). We calculated the minimum gm as: gmmin=A/Ci (von Caemmerer et al., 2014). These results showed that gmmin decreased with increasing Ci (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Further, we assumed that the young leaves of C. squarrosa had a gm of 0.66 mol m−2 s−1 at the growth Ca of 390 μmol mol−1. Appling a constant ratio of gm/gmmin across the CO2 response curve, we estimated the response of gm to Ci. The estimates of gm ranged between 0.2 and 2.4 mol m−2 s−1 and decreased with increasing Ci (Supplementary Fig. S2); similarly, decrease of gm with increasing Ci was found in other C4 species using the oxygen isotope approach (Osborn et al., 2016) or an ‘in vitro Vpmax’ method (N. Ubierna, personal communication).

A simplified version of the C4 photosynthesis model for enzyme-limited CO2 assimilation rate (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999) can be used to model the photosynthetic CO2 response curve: A=min[(Vp−Rm+gbsCm), (Vcmax−RL)], where VP is the rate of PEP carboxylation, Vcmax is the maximum rate of Rubisco carboxylation, and gbs is the bundle-sheath conductance to CO2. A is determined by the term Vcmax−RL at high CO2 concentrations. According to this model, we assumed that Vcmax=Amax+RL, where Amax is the maximum net assimilation rate observed in the photosynthetic light response curves measured on leaves of the same age at ambient CO2 (data shown in Supplementary Fig. S3). Treatment-specific Vcmax of C. squarrosa ranged between 16 and 19 μmol m−2 s−1, which is in the range of Vcmax of C4 grass used in Earth System Models (13–33 μmol m−2 s−1; Rogers, 2014). Cbs was estimated using equations of von Caemmerer and Furbank (1999):

| (11) |

| (12) |

where Obs is the bundle-sheath oxygen concentration, and Om (210 mmol mol−1) is the oxygen concentration in mesophyll cells; γ* (0.000193) is half of the reciprocal of Rubisco specificity; Kc and Ko are the Michaelis–Menten constants of Rubisco for CO2 (650 μmol mol−1) and O2 (450 μmol mol−1) at 25 °C, respectively; α (0.1) is the fraction of PSII activity in the bundle-sheath; gbs=0.003 mol m−2 s−1. Furthermore, Vo/Vc was calculated as Vo/Vc=2γ*Obs/Cbs. Knowing Vo/Vc, Vo and Vc were calculated using the equation: Vc=A+RL+0.5Vo. The values of model parameters and equations were derived from von Caemmerer and Furbank (1999). Knowing ϕ and applying the assumption that Rm=Rbs=0.5RL (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Pengelly et al., 2010), the rate of PEP carboxylation (Vp) or Rubisco carboxylation (Vc) was estimated (see Supplementary Fig. S4). As Cm and Cbs cannot be directly measured, the determination of both parameters in this study was associated with some uncertainty. Another commonly used assumption in calculating leakiness using the complete or simplified version of Eqn 6 is that CO2 is in equilibrium with HCO3− in the mesophyll cytoplasm. The extent of this equilibrium is determined by the relative rate of PEP carboxylation and hydration of CO2 (Vh). If CO2 is not in equilibrium with HCO3−, b′4 of –5.7‰ in Eqn 9 should be replaced by b′4=–5.7 + 7.9Vp/Vh (Farquhar 1983). Thus, we calculated ϕ using C4 discrimination models with different assumptions on gm, Cbs, and Vp/Vh (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results are compared and discussed below.

Fitting of CO2 response curves

For each plant, measured A was plotted against the respective intercellular CO2 concentration. A model of C4 photosynthesis was used to fit the CO2 response curves (Wang et al., 2012):

| (13) |

where x is Ci and c′ is RL. Using the fitted parameters (a′ and b′) of each CO2 response curve, CO2-saturated net assimilation rate (Asat) was obtained as (a′+c′), and carboxylation efficiency (CE) was calculated as b′(a′+c′) (the initial slope of the A–Ci curve). For CO2 response curves of C4 leaves, Asat is proportional to Rubisco activity, while CE is proportional to the PEP carboxylase activity (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Yin et al., 2011). The ratio of Asat to CE was calculated to indicate the ratio of Rubisco to PEPc activities.

Leaf trait parameters and nitrogen nutrition index

N content in dry mass of leaves previously used for gas exchange measurements was measured using an elemental analyser (NA 1110, Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy). For sample preparation, leaves were dried at 60 °C for 48 h, weighed and then milled. N content on a mass (Nmass, %DM) and leaf area basis (Narea, g m−2) were calculated. Specific leaf area (SLA, cm2 mg−1) was obtained as SLA=leaf area/leaf dry mass. In each experiment, a set of individual plants (four plants per chamber) were sampled four or five times (twice per week) after canopy closure (when leaf area index was >2) for the determination of standing aboveground biomass, and N content in total aboveground dry mass. Those data were used to calculate nitrogen nutrition index (NNI) according to Lemaire et al. (2008).

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of N supply, VPD, and their interactions on leaf traits and gas exchange parameters, using general linear models of SAS (SAS 9.1, SAS Institute, USA). The effects of N nutrition and VPD on the relationship between lnCi and leakiness were analysed using a dummy regression approach; the parallelism and coincidence of linear regressions of different treatments were tested according to Berenson et al. (1983). Non-linear regression analysis on photosynthetic CO2 response curve of individual plants was performed using the Nlin procedure of SAS.

Results

Leaf traits and photosynthetic CO2 assimilation

N supply increased Nmass of fully expanded young leaves by 25% (P<0.05) and also tended to increase Narea (P=0.06), but had no effect on SLA (Table 1). N supply also significantly increased nitrogen nutrition index (NNI; determined from N content and aboveground standing biomass of each stand): NNI was 0.88 ± 0.05 (mean±SD, n=4 replicate stands) for the N1V1 treatment, 0.71±0.06 for the N1V2 treatment, 1.25±0.06 for the N2V1 treatment, and 1.32±0.05 for the N2V2 treatment. The effects of VPD and the interaction of VPD and N supply on Nmass, Narea and SLA were all non-significant (P>0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Leaf trait and gas exchange parameters of C. squarrosa measured under the same environmental conditions as during growth (leaf temperature 25 °C, PPFD 800 μmol m−2s−1, [CO2] 390 μmol mol−1, VPD 0.8 kPa for V1 and 1.6 kPa for V2)

Plants were grown at low or high N fertilizer supply (N1 or N2) combined with low or high VPD (V1 or V2). Leaf trait parameters include N content per unit dry mass (Nmass, % DM) and per leaf area (Narea, g m−2), and specific leaf area (SLA, cm2 mg−1). Gas exchange parameters: net CO2 assimilation rate (A, μmol m−2 s−1), transpiration rate (E, mmol m−2 s−1), stomatal conductance to water vapor (gs, mol m−2 s−1), respiration rate in light (RL, μmol m−2 s−1), the ratio of internal to atmospheric CO2 concentration (Ci/Ca), instantaneous water use efficiency (WUEins=A/E, mmol mol−1), and intrinsic water use efficiency (WUEi=A/gs, μmol mol−1). Data are shown as mean±SE (n=6 for RL, n=9–10 for the other parameters). Significant treatment effects (P<0.05) are shown in bold.

| N1 | N2 | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | V1 | V2 | N | VPD | N×VPD | |

| Nmass | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.79 |

| Narea | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.82 | 0.92 |

| SLA | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| A | 14.8 ± 0.9 | 13.1 ± 0.9 | 14.9 ± 0.9 | 12.3 ± 1.0 | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.58 |

| E | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.60 |

| g s | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.45 |

| R L | 0.81 ± 0.26 | 0.62 ± 0.30 | 0.53 ± 0.10 | 0.51 ± 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.71 |

| C i/Ca | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| WUEins | 15.9 ± 0.6 | 11.7 ± 0.6 | 16.8 ± 0.6 | 10.0 ± 0.6 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| WUEi | 153 ± 9 | 173 ± 9 | 154 ± 9 | 178 ± 10 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.82 |

The effects of N supply on Nmass and Narea were not associated with parallel effects on gas exchange parameters measured at growth CO2 level (390 μmol mol−1). Thus, N supply had no effect on A, E, gs, Ci/Ca, and WUEins, and there was only a small interactive effect of N and VPD on WUEi (Table 1). Conversely, VPD during growth had significant effects on all these parameters, but none of these effects demonstrated an interaction with N supply except for WUEins. High VPD decreased A by 14%, gs by 29%, Ci/Ca by 27% at both low and high N, and WUEins by 26% at low N and 40% at high N. Conversely, high VPD increased E by 27% and WUEi by 14% independently of N levels (Table 1). The rate of leaf respiration in light (RL) did not differ between treatments.

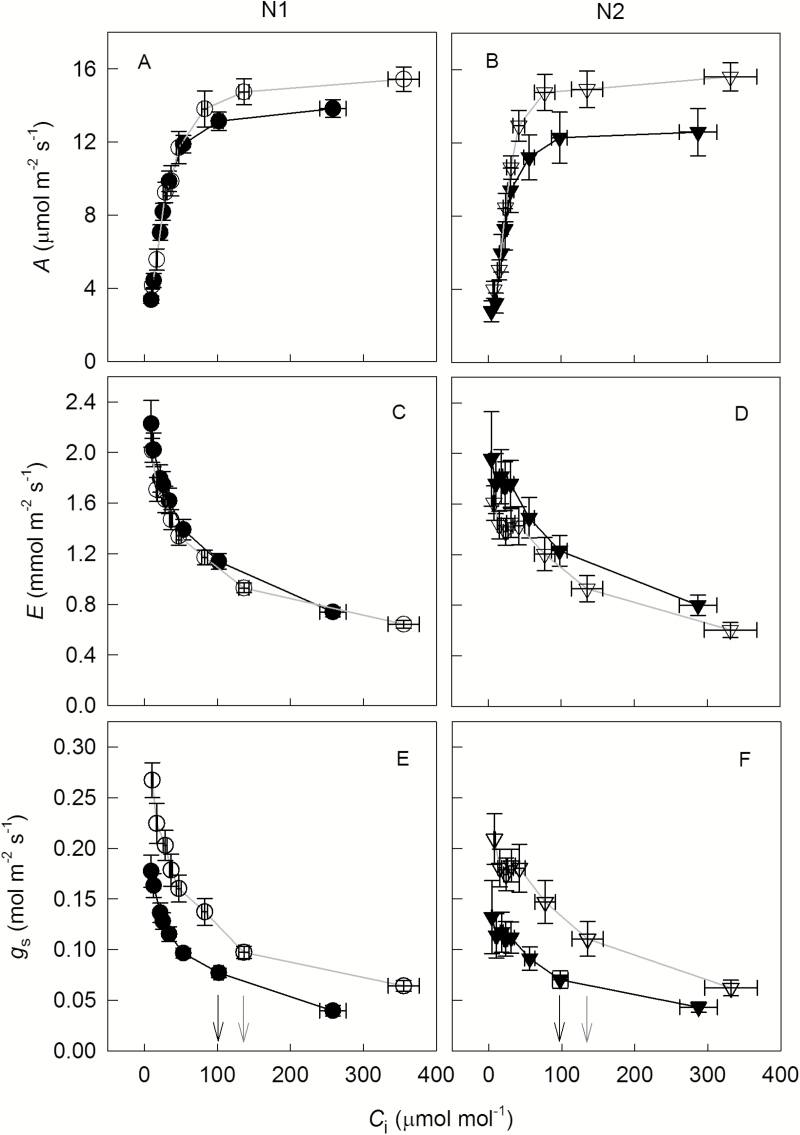

The response of photosynthetic gas exchange parameters to dynamic changes of CO2 concentration (Fig. 1) showed typical CO2 responses of net CO2 assimilation rate. VPD had clear effects on gas exchange parameters: compared with low VPD, A was 20% lower (Fig. 1A, B), E was 21% higher (Fig. 1C, D), and gs was 32% lower (Fig. 1E, F) at high VPD averaged over N levels and CO2 concentrations.

Fig. 1.

Net CO2 assimilation rate (A; A, B), transpiration rate (E; C, D) and stomatal conductance to water vapour (gs; E, F) in response to short-term variation of intercellular CO2 (Ci) under low (N1, circles; A, C, E) or high N supply (N2, triangles; B, D, F) combined with low (V1, open symbols) or high VPD (V2, filled symbols). Data are shown as the mean±SE (n=9–10). Operating conditions of gas exchange measurements were the same as conditions in growth chambers (leaf temperature 25 °C, PPFD 800 μmol m−2 s−1, VPD 0.8 kPa for V1 and 1.6 kPa for V2). The corresponding Ci values at growth CO2 concentration (390 μmol mol−1) are indicated by grey (low VPD) and black arrows (high VPD) in (E) and (F).

Carbon isotope discrimination and bundle-sheath leakiness

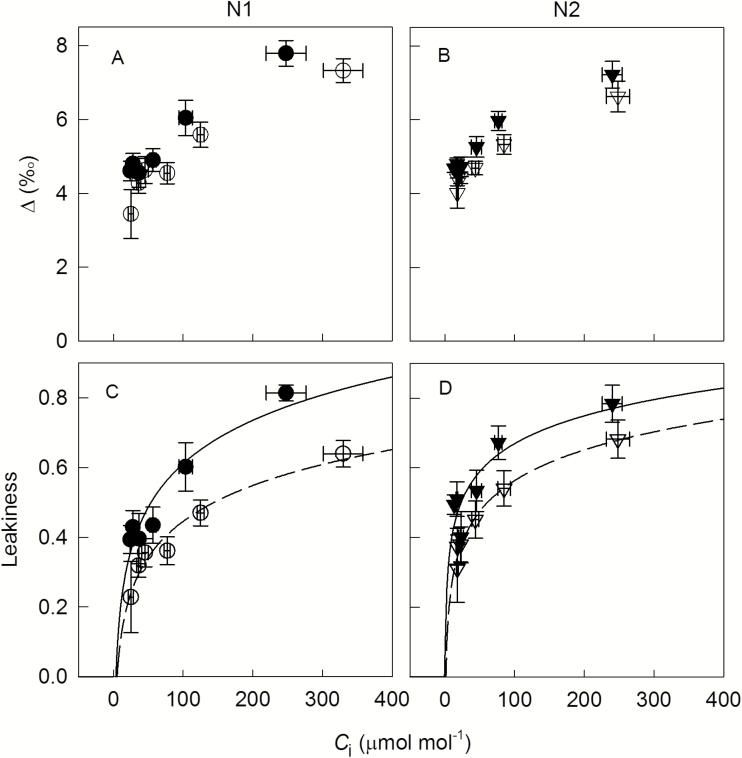

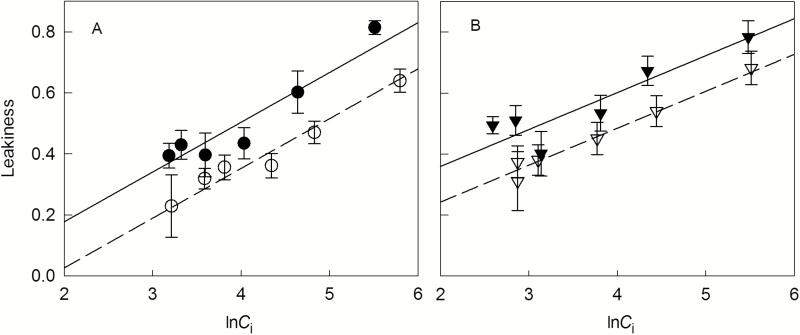

Carbon isotope discrimination (∆) during net CO2 exchange revealed strong dynamic responses to short-term variation of CO2 concentration; ∆ increased with increasing Ci in all treatments, and ranged from 4 to 8‰ (Fig. 2A, B). Compared at the same Ci, ∆ was higher at high VPD than at low VPD. Estimates of ϕ also increased with increasing Ci in all treatments, and ranged from 0.23 to 0.81 (Fig. 2C, D). The relationship between Ci and ϕ followed a logarithmic function. Regression analyses between lnCi and ϕ including VPD as a dummy variable indicated a significant VPD effect on ϕ: ϕ was higher by 0.13 at high VPD than at low VPD at both N levels (Fig. 3, Table 2). Plants grown with high N supply had a higher ϕ at moderate to low Ci (Ca≤390) than plants with low N supply (Fig. 3). Accordingly, the slope of the linear regression between lnCi and ϕ was significantly lower for the high N treatment than for the low N treatment (Table 2). The increase of ϕ along the gradient of Ci was apparently related to the discrepancy between rates of C3 and C4 cycles: Vc already reached the maximum at a Ci<100 μmol mol−1, while Vp increased throughout the range of measured Ci (Supplementary Fig. S4). We also calculated ϕ using C4 discrimination models with different assumptions on gm, Cbs, and Vp/Vh, and our conclusions on short-term response to CO2 and long-term response to VPD and N were not altered (see Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Carbon isotope discrimination (∆) during net CO2 exchange (A, B) and bundle sheath leakiness (C, D) of Cleistogenes squarrosa leaves in response to short-term variation of intercellular CO2 (Ci). Plants were grown under low (N1, circles; A, C) or high N supply (N2, triangles; B, D) combined with low (V1, open symbols, dashed lines) or high VPD (V2, filled symbols, solid lines). Operating conditions of gas exchange measurements were the same as conditions in growth chambers (leaf temperature 25 °C, PPFD 800 μmol m−2 s−1, VPD 0.8 kPa for V1 and 1.6 kPa for V2). Data are shown as the mean±SE (n=5–6). The regressions were fitted using a function of y=y0+aln(x); all regressions have r2>0.8.

Fig. 3.

Relationships between bundle sheath leakiness and ln(Ci) under low (N1, circles; A) or high N supply (N2, triangles; B) combined with low (V1, open symbols, dashed lines) or high VPD (V2, filled symbols, solid lines). Operating conditions of gas exchange measurements were the same as conditions in growth chambers (leaf temperature 25 °C, PPFD 800 μmol m−2 s−1, VPD 0.8 kPa for V1 and 1.6 kPa for V2). Data are shown as the mean±SE (n=5–6). The data of each N level were fitted by linear regression including a dummy variable indicating VPD treatments (V) after the confirmation of parallelism of the two regressions of VPD levels: with V=0 for low VPD and V=1 for high VPD (for equations see Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of regression analysis on the relationship between Ciand leakiness (ϕ)

The data for each N level were fitted by linear regression including a dummy variable indicating VPD treatments (V) after the confirmation of parallelism of the two regressions of VPD levels, with V=0 for low VPD and V=1 for high VPD; 95% confidence intervals of slope and coefficient of dummy variable (V) are shown. The coefficient of V quantifies the mean difference in ϕ between high and low VPD treatments across Ci levels. Both regressions are significant (P<0.001).

| N level | equation | r 2 | 95% CI slope | 95% CI coeff. V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | ϕ =−0.30+0.16lnCi+0.15V | 0.94 | 0.13~0.20 | 0.09~0.21 |

| N2 | ϕ =0.001+0.12lnCi+0.12V | 0.91 | 0.09~0.15 | 0.05~0.18 |

Relationships between leaf traits and gas exchange parameters

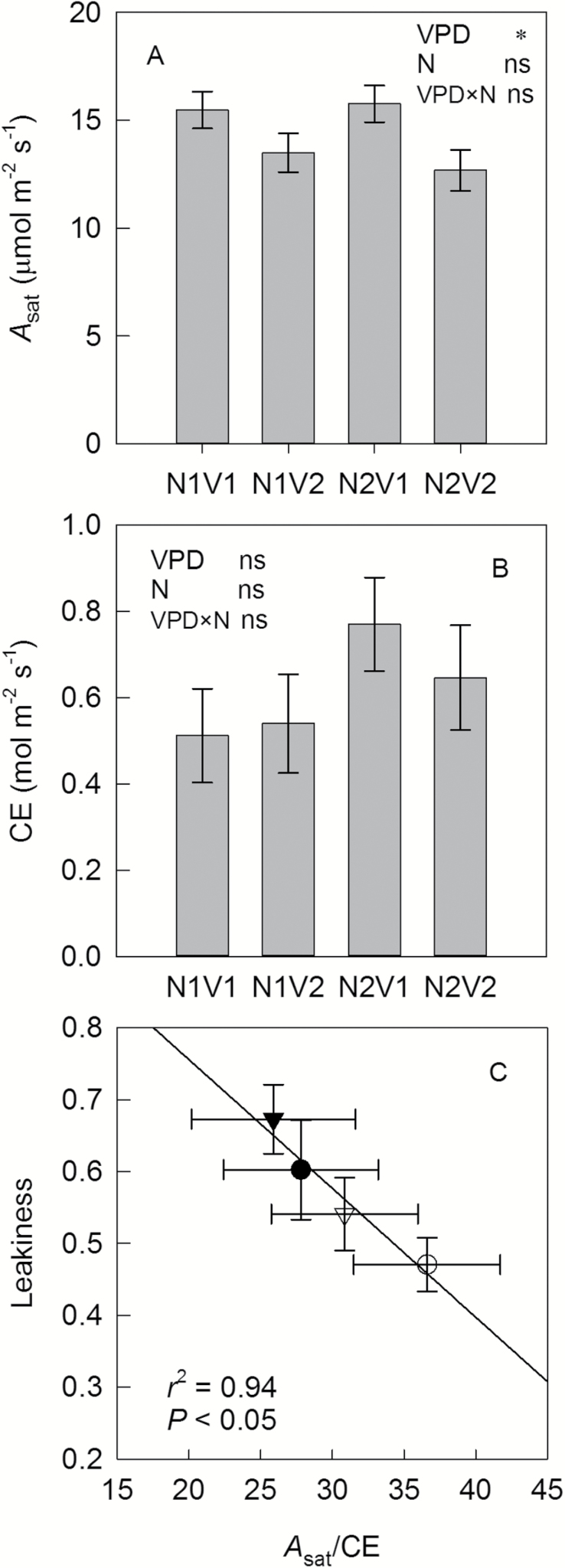

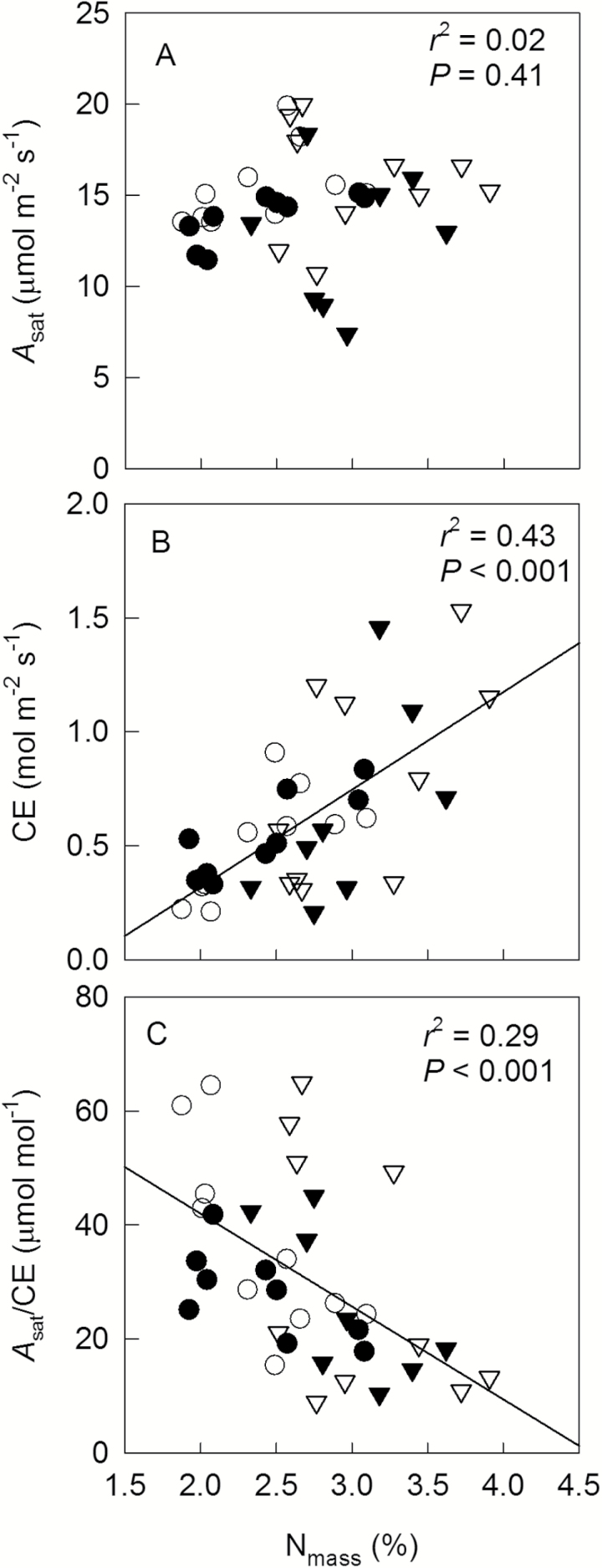

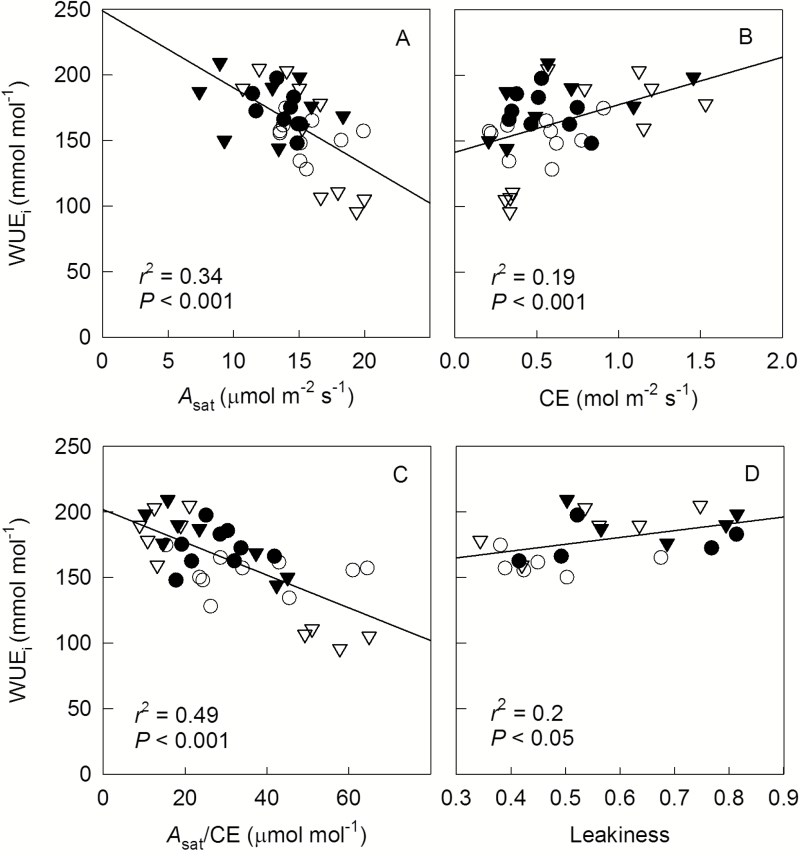

VPD had a clear effect on Asat (Fig. 4A): averaged over N treatments, high VPD caused a 15% reduction of Asat. N supply and N×VPD interactions had no effect on Asat. CE of leaves seemed to be slightly higher at high (0.71 mol m−2 s−1) than low N (0.53 mol m−2 s−1), although this effect was only significant at P=0.10 (Fig. 4B). Asat/CE was calculated to indicate the ratio of Rubisco to PEPc activities. Treatment-specific mean Asat/CE was negatively correlated with ϕ (P<0.05, Fig. 4C). Across all treatments, we found no correlation between Asat and Nmass (P=0.41, Fig. 5A), but a positive correlation between CE and Nmass (r2=0.43, P<0.001, Fig. 5B) and a negative correlation between Asat/CE and Nmass (r2=0.29, P<0.001, Fig. 5C). WUEi was negatively correlated with Asat (r2=0.34, P<0.001, Fig. 6A) and Asat/CE (r2=0.49, P<0.001, Fig. 6C), but positively with CE (r2=0.19, P<0.001, Fig. 6B) and leakiness (r2=0.19, P<0.05, Fig. 6D). Furthermore, a positive correlation between WUEi and leakiness was also found during short-term response to CO2 (r2>0.9, P<0.01, Supplementary Fig. S6).

Fig. 4.

A sat (A), carboxylation efficiency (CE; B) and the relationship between leakiness measured under growth conditions (390 μmol mol−1) and Asat/CE (μmol mol−1; C) under low or high N fertilizer supply (N1, circles; or N2, triangles) combined with low or high VPD (V1, open symbols; or V2, filled symbols). Data are shown as the mean±SE (n=9–10 for Asat and CE, n=5–6 for leakiness). * indicates the treatment effect was significant at the P-level of 0.05, while ns indicates no significant effect.

Fig. 5.

Correlations between Nmass and Asat (A), CE (B) and Asat/CE (C) of leaves grown at low or high N fertilizer supply (N1, circles; or N2, triangles) combined with low or high VPD (V1, open symbols; or V2, filled symbols). Each symbol represents a data point of an individual plant.

Fig. 6.

Correlations between WUEi and Asat (A), CE (B), Asat/CE (C), and leakiness (D) of leaves grown at low or high N fertilizer supply (N1, circles; or N2, triangles) combined with low or high VPD (V1, open symbols; or V2, filled symbols). Each symbol represents a data point of an individual plant.

Discussion

This study indicates an effect of VPD of the growth environment on bundle-sheath leakiness: ϕ was higher at high VPD than at low VPD with an absolute difference of 0.13 at both N supply levels. This effect appeared to be constitutive, as it was manifest throughout a wide range of short-term variations of CO2 concentration. Remarkably, the higher leakiness at high VPD was associated with a 14% improved WUEi. Also, we observed an N effect on ϕ that responded to short-term variation of CO2 levels: high N supply increased ϕ of leaves at ambient to low CO2 levels (Ca≤390 μmol mol−1). Further, ϕ responded dynamically to short-term changes of [CO2], in support of theoretical predictions of C4 photosynthesis models (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Yin et al., 2011). Lastly, across treatments, a positive correlation between WUEi and leakiness was evident, pointing to a trade-off between WUEi and energy use efficiency of this species.

Unfortunately, leakiness cannot be measured directly, and the online ∆13C approach for estimations of leakiness in conjunction with the C4 photosynthetic discrimination model of Farquhar (1983) can lead to inaccurate estimates of leakiness if improper simplifications are made (Ubierna et al., 2011, 2013; Gong et al., 2015). One commonly used assumption is that gm of C4 plants is infinite, and thus Ci=Cm. However, a recent study indicated that gm of C4 plants is finite, although close to the high-end values of gm of C3 plants (Barbour et al., 2016). In our study, assuming a lower range of gm across Ci levels (see Supplementary Fig. S5), or a constant gm of 1.8 mol m−2 s−1 (data not shown) or an infinite gm (Supplementary Fig. S5) did not modify observed treatment effects. Only if gm was much lower at low compared with high VPD (e.g. gm at N1V1 was 60% lower than at N1V2 treatment), would VPD effects on leakiness disappear. However, it is unlikely that C. squarrosa had lower gm at low than at high VPD, as studies with C3 species generally showed a decrease of gm by high VPD or water stress (Flexas et al., 2008). Thus, our estimates of treatment effects on leakiness appeared to be largely insensitive to assumptions on gm.

Many studies using Eqn 6 have assumed that CO2 is in equilibrium with HCO3− in the mesophyll cytoplasm. However, according to Cousins et al. (2008) that assumption might not be proper, especially for C4 grasses, which have lower carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity than C4 dicots. Our observations with the same species in the same experiment suggested that, under growth conditions, assimilated CO2 was in equilibrium with HCO3−, as indicated by the fact that δ18O of leaf cellulose did not differ between plants growing in the presence of CO2 with contrasting δ18O (Liu et al., 2016). Thus the observed treatment effects on leakiness of C. squarrosa seemed not to be related to CA activity. Further, we calculated leakiness using different assumptions on Vp/Vh: Vp/Vh=0 or Vp/Vh=0.23 (mean of NAD-ME grasses in Cousins et al., 2008) and observed a minor effect on leakiness (less than 0.06). Thus, the short-term response of leakiness to CO2 was not explained by changes in Vp/Vh. Applying another commonly used simplification that Cbs is sufficiently higher than Cm, so that Cbs/(Cbs−Cm)=1 and Cm/(Cbs−Cm)=0, also had no influence on our conclusions on effects of environmental factors on leakiness.

Effects of VPD and N nutrition on bundle-sheath leakiness

The study demonstrated a higher leakiness of plants grown at high VPD than at low VPD, and this effect was not modified by N nutrition. The present effect was not related to drought stress, as the elongation rate of phytomers ( Yang et al., 2016a) and the growth rate of individuals (Liu et al., 2016) were not influenced by VPD. The long-term response of leakiness to VPD was related to the decrease of Ci/Ca and the increase of ∆ (0.55‰ at ambient CO2 level) at high VPD, although the direct and indirect influences cannot be clearly distinguished due to the intrinsic correlation between Ci/Ca and ∆. The latter observation was also supported by the 13C discrimination of leaf dry mass, which was significantly higher at high VPD (5.0±0.2‰, averaged over N levels) than at low VPD treatment (4.4±0.2‰). Likely, the higher leakiness at high VPD resulted from an enhanced capacity of the C4 cycle relative to the C3 cycle at low gs, as was supported by the lower Asat/CE ratio and the lower Ci/Ca at high VPD relative to low VPD. This interpretation is in line with the findings that the relative activities of Rubisco/PEPc decreased at low gs under water stress, with the adjustment achieved by increasing activity of PEPc (Saliendra et al., 1996; Foyer et al., 1998) or decreasing sensitivity of PEPc to the inhibitor malate (Foyer et al., 1998). Also, the data may shed light on the mechanism that underlies the increased leakiness under limited water supply (Saliendra et al., 1996; Williams et al., 2001; Fravolini et al., 2002): that response may have been triggered by decreased stomatal conductance at high VPD. Although a VPD effect on this relationship has not yet been reported, the adjustment of Rubisco/PEPc activities seems to be an important mechanism for plants to counteract the reduced gs under long-term low water supply (Saliendra et al., 1996) or high VPD. Maintaining a powerful C4 pump (at the expense of increased leakiness) might reduce the quantum yield due to the additional ATP requirement for PEP regeneration (Hatch, 1987; Furbank et al., 1990). However, this mechanism may be beneficial for plants to maintain a high WUEi under high VPD or drought stress.

In this work, high N nutrition increased leakiness in short-term exposures to subambient to ambient [CO2], but not to elevated [CO2] of 800 μmol mol−1. This result is at variance with previous reports of a higher leakiness of plants growing with a low N supply (Meinzer and Zhu, 1998; Fravolini et al., 2002). Other studies also reported non-significant effects of N supply on leakiness (Fravolini et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2012). In the present study, the plants of the low N treatment had a nitrogen nutrition index of ~0.8, which indicated that N was just growth limiting. High N supply led to a NNI of 1.3, and increased plant growth rate via stimulated tiller production (data not shown), but leaf-level net assimilation rates of young leaves were not affected. These results indicate that our low N and high N treatment represented rather ‘nearly-adequate’ and ‘copious supply’ of N for leaf-level photosynthesis. High N supply increased leakiness, in correspondence with a lower Asat/CE ratio, again indicating the involvement of the relative activities of Rubisco/PEPc. This interpretation was further supported by the positive correlation between Nmass and CE, and simultaneous absence of such a relationship between Nmass and Asat. These results suggest that under copious N supply to C. squarrosa, the activity of PEPc was more strongly enhanced relative to that of Rubisco, in line with experimental results on Amaranthus retroflexus (Sage et al., 1987). Thus, our results are also in agreement with the hypothesis that C4 plants have less plasticity in increasing the amount of Rubisco compared with C3 plants, due to spatial restrictions in bundle-sheath cells (Sage and McKown, 2006).

Another potential origin of the variance in leakiness is related to the bundle-sheath conductance (gbs=ϕVP/(Cbs−Cm)). However, current understanding on gbs is limited due to the lack of a methodology for quantification of gbs that is independent of gas exchange measurements. Furthermore, it is unknown how VPD may affect the properties of bundle-sheath cell walls, limiting to some extent discussions of potential mechanisms. A recent study demonstrated that Miscanthus×giganteus plants grown at high N supply had higher bundle-sheath area per unit leaf area, which might increase gbs; however, estimates of leakiness did not differ between N levels (Ma et al., 2016). Such results highlight the potential complexity of influences on leakiness by biochemical/physiological and anatomical features. In our study, treatments had little effect on individual leaf area and no effect on thickness (Liu et al., 2016), indicating that effects of leaf anatomy may have been minor. Across all treatments, leakiness measured under growth conditions was negatively related to Asat/CE, again suggesting that variations of leakiness across treatments was related to the balance between C3 and C4 cycles.

Response of bundle-sheath leakiness to short-term variation of CO2

The response of ϕ to short-term variation of [CO2] has been predicted by model analyses (von Caemmerer and Furbank, 1999; Kiirats et al., 2002; Ghannoum, 2009; Yin et al., 2011). Although these models were designed for estimating gas exchange rate rather than leakiness, the present results supported the theoretical predictions. So far, only a small number of studies investigated the response of ϕ to dynamic changes of [CO2]. A study using the on-line ∆ method showed no response of ϕ of F. bidentis to dynamic changes of CO2 (Pengelly et al., 2012), in agreement with the finding of an earlier study on several species (Henderson et al., 1992). However, in the latter study, each leaf was measured at only two or three levels of CO2. Those results suggested a rapid regulation of C3 and C4 cycle rates in response to changing CO2 concentrations. The present results indicate that this kind of regulation did not occur to the same extent during short-term CO2 responses in C. squarrosa. Clearly, the response of ϕ to short-term variation of CO2 should be studied in detail with a greater number of species.

Implications on the ecophysiology of C. squarrosa

This work questions the interpretation of leakiness as a simple indicator for efficiency of C4 photosynthesis or physiological fitness of C4 plants, as increased leakiness was related to the enhancement of WUEi in C. squarrosa. The latter observation was consistent across N and VPD treatments (long-term response) and short-term variation of CO2 levels. This result was in line with the theoretical prediction of the simplified model of C4 discrimination: WUEi is positively correlated to leakiness when ∆>4.4‰, i.e. when ϕ>0.37. This relationship indicates a potential trade-off between quantum yield and water use efficiency: high leakiness under VPD stress might decrease the efficiency of energy use, but may be a condition for maintaining the effectiveness of CCM and minimizing photorespiration at a very low gs in this species. This mechanism is meaningful for C4 species in arid or semi-arid grasslands, where shading is uncommon but high VPD or drought stress is a common attribute of the habitat. Considering the reduction of Rubisco specificity for CO2 relative to O2 by the increase of leaf temperature, this trade-off may be important for C4 plants in the context of global warming. Observational evidence has indeed shown that this C4 grass has increased its relative abundance in vast areas of Inner Mongolian grasslands during regional warming in the last decades (Wittmer et al., 2010).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Relative humidity and leaf-to-air vapour pressure deficit in the leaf cuvette during the measurement of CO2 response curves.

Fig. S2. Minimum mesophyll conductance to CO2 (gmmin=A/Ci) and estimated gm in response to Ci.

Fig. S3. Photosynthetic light response curves of leaves of C. squarrosa.

Fig. S4. Vp and Vc in response to Ci.

Fig. S5. Bundle-sheath leakiness in response to Ci, calculated using different models of 13C discrimination.

Fig. S6. Correlations between WUEi and bundle-sheath leakiness of C. squarrosa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SCHN 557/7-1). Wolfgang Feneis and Richard Wenzel are thanked for assistance with technical facilities. We thank Prof. von Caemmerer and two anonymous referees for constructive comments and suggestions that helped us to improve this work.

References

- Barbour MM, Evans JR, Simonin KA, von Caemmerer S. 2016. Online CO2 and H2O oxygen isotope fractionation allows estimation of mesophyll conductance in C4 plants, and reveals that mesophyll conductance decreases as leaves age in both C4 and C3 plants. New Phytologist 210, 875–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014. Acclimation to low light by C4 maize: implications for bundle sheath leakiness. Plant, Cell and Environment 37, 1046–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenson ML, Levine DM, Goldstein M. 1983. Intermediate statistical methods and applications: A computer package approach. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. 2008. C4 photosynthetic isotope exchange in NAD-ME- and NADP-ME-type grasses. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Cerling TE, Helliker BR. 1997. C4 photosynthesis, atmospheric CO2, and climate. Oecologia 112, 285–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsig J, Leuenberger MC. 2010. 13C and 18O fractionation effects on open splits and on the ion source in continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 24, 1419–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Sharkey TD, Berry JA, Farquhar GD. 1986. Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas-exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 13, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. 1983. On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 10, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA. 2012. Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Richards RA. 1984. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 11, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbo M, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmes J, Medrano H. 2008. Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant, Cell and Environment 31, 602–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Valadier MH, Migge A, Becker TW. 1998. Drought-induced effects on nitrate reductase activity and mRNA and on the coordination of nitrogen and carbon metabolism in maize leaves. Plant Physiology 117, 283–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fravolini A, Williams DG, Thompson TL. 2002. Carbon isotope discrimination and bundle sheath leakiness in three C4 subtypes grown under variable nitrogen, water and atmospheric CO2 supply. Journal of Experimental Botany 53, 2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Hatch MD. 1990. C4 photosynthesis: quantum requirement, C4 and overcycling and Q-cycle involvement. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O. 2009. C4 Photosynthesis and water stress. Annals of Botany 103, 635–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghashghaie J, Badeck F-W, Lanigan G, Nogués S, Tcherkez G, Deléens E, Cornic G, Griffiths H. 2003. Carbon isotope fractionation during dark respiration and photorespiration in C3 plants. Phytochemistry Reviews 2, 145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Chen Q, Lin S, Brueck H, Dittert K, Taube F, Schnyder H. 2011. Tradeoffs between nitrogen- and water-use efficiency in dominant species of the semiarid steppe of Inner Mongolia. Plant and Soil 340, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gong XY, Schäufele R, Feneis W, Schnyder H. 2015. 13CO2/12CO2 exchange fluxes in a clamp-on leaf cuvette: disentangling artefacts and flux components. Plant, Cell and Environment 38, 2417–2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresset S, Westermeier P, Rademacher S, Ouzunova M, Presterl T, Westhoff P, Schön CC. 2014. Stable carbon isotope discrimination is under genetic control in the C4 species maize with several genomic regions influencing trait expression. Plant Physiology 164, 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. 1987. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 895, 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. 1992. Short-term measurements of carbon isotope discrimination in several C4 species. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 19, 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD, Wade L, Hammer H. 1998. Correlation between carbon isotope discrimination and transpiration efficiency in lines of the C4 species Sorghum bicolor in the glasshouse and the field. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology 25, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kiirats O, Lea PJ, Franceschi VR, Edwards GE. 2002. Bundle sheath diffusive resistance to CO2 and effectiveness of C4 photosynthesis and refixation of photorespired CO2 in a C4 cycle mutant and wild-type Amaranthus edulis. Plant Physiology 130, 964–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Griffiths H, Schepers HE. 2010. Can the progressive increase of C4 bundle sheath leakiness at low PFD be explained by incomplete suppression of photorespiration?Plant, Cell and Environment 33, 1935–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanigan GJ, Betson N, Griffiths H, Seibt U. 2008. Carbon isotope fractionation during photorespiration and carboxylation in Senecio. Plant Physiology 148, 2013–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmeier CA, Lattanzi FA, Schäufele R, Wild M, Schnyder H. 2008. Root and shoot respiration of perennial ryegrass are supplied by the same substrate pools: assessment by dynamic 13C labeling and compartmental analysis of tracer kinetics. Plant Physiology 148, 1148–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire G, Jeuffroy MH, Gastal F. 2008. Diagnosis tool for plant and crop N status in vegetative stage theory and practices for crop N management. European Journal of Agronomy 28, 614–624. [Google Scholar]

- Liu HT, Gong XY, Schäufele R, Yang F, Hirl RT, Schmidt A, Schnyder H. 2016. Nitrogen fertilization and δ18O of CO2 have no effect on 18O-enrichment of leaf water and cellulose in Cleistogenes squarrosa (C4) – is VPD the sole control?Plant, Cell and Environment, DOI: 10.1111/pce.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP. 1999. Environmental responses. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, eds. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press, 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Sun W, Koteyeva NK, Voznesenskaya E, Stutz SS, Gandin A, Smith-Moritz AM, Heazlewood JL, Cousins AB. 2016. Influence of light and nitrogen on the photosynthetic efficiency in the C4 plant Miscanthus × giganteus. Photosynthesis Research, DOI: 10.1007/s11120-016-0281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer F, Zhu J. 1998. Nitrogen stress reduces the efficiency of the C4 CO2 concentrating system, and therefore quantum yield, in Saccharum (sugarcane) species. Journal of Experimental Botany 49, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn HL, Alonso-Cantabrana H, Sharwood RE, Covshoff S, Evans JR, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2016. Effects of reduced carbonic anhydrase activity on CO2 assimilation rates in Setaria viridis: a transgenic analysis. Journal of Experimental Botany, DOI: 10.1093/jxb/erw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengelly JJL, Sirault XRR, Tazoe Y, Evans JR, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2010. Growth of the C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis: photosynthetic acclimation to low light through shifts in leaf anatomy and biochemistry. Journal of Experimental Botany 61, 4109–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengelly JJL, Tan J, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2012. Antisense reduction of NADP-malic enzyme in Flaveria bidentis reduces flow of CO2 through the C4 cycle. Plant Physiology 160, 1070–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyankov VI, Gunin PD, Tsoog S, Black CC. 2000. C4 plants in the vegetation of Mongolia: their natural occurrence and geographical distribution in relation to climate. Oecologia 123, 15–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers A. 2014. The use and misuse of Vc,max in Earth System Models. Photosynthesis Research 119, 15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, McKown AD. 2006. Is C4 photosynthesis less phenotypically plastic than C3 photosynthesis?Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 303–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Pearcy RW, Seemann JR. 1987. The nitrogen use efficiency of C3 and C4 Plants III. Leaf nitrogen effects on the activity of carboxylating enzymes in Chenopodium album (L) and Amaranthus retroflexus (L). Plant Physiology 85, 355–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliendra NZ, Meinzer FC, Perry M, Thom M. 1996. Associations between partitioning of carboxylase activity and bundle sheath leakiness to CO2, carbon isotope discrimination, photosynthesis, and growth in sugarcane. Journal of Experimental Botany 47, 907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder H, Schäufele R, Lötscher M, Gebbing T. 2003. Disentangling CO2 fluxes: direct measurements of mesocosm-scale natural abundance 13CO2/12CO2 gas exchange, 13C discrimination, and labelling of CO2 exchange flux components in controlled environments. Plant, Cell and Environment 26, 1863–1874. [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Cousins AB. 2011. The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions: assumptions and calculations with CO2 isotope discrimination. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 3119–3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubierna N, Sun W, Kramer DM, Cousins AB. 2013. The efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under low light conditions in Zea mays, Miscanthus x giganteus and Flaveria bidentis. Plant, Cell and Environment 36, 365–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Furbank RT. 1999. Modeling C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, eds. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press, 173–211. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Ghannoum O, Pengelly JJL, Cousins AB. 2014. Carbon isotope discrimination as a tool to explore C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3459–3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZC, Kang SZ, Jensen CR, Liu FL. 2012. Alternate partial root-zone irrigation reduces bundle-sheath cell leakage to CO2 and enhances photosynthetic capacity in maize leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 1145–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watling JR, Press MC, Quick WP. 2000. Elevated CO2 induces biochemical and ultrastructural changes in leaves of the C4 cereal sorghum. Plant Physiology 123, 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DG, Gempko V, Fravolini A, Leavitt SW, Wall GW, Kimball BA, Pinter PJ, Jr, LaMorte R, Ottman M. 2001. Carbon isotope discrimination by Sorghum bicolor under CO2 enrichment and drought. New Phytologist 150, 285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wittmer MHOM, Auerswald K, Bai Y, Schäufele R, Schnyder H. 2010. Changes in the abundance of C3/C4 species of Inner Mongolia grassland: evidence from isotopic composition of soil and vegetation. Global Change Biology 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Auerswald K, Bai Y, Wittmer MHOM, Schnyder H. 2011. Variation in carbon isotope discrimination in Cleistogenes squarrosa (Trin.) Keng: patterns and drivers at tiller, local, catchment, and regional scales. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 4143–4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Gong XY, Liu HT, Schäufele R, Schnyder H. 2016a Effects of nitrogen and vapour pressure deficit on phytomer growth and development in a C4 grass. AoB Plants, doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plw075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Liu J, Tischer SV, Christmann A, Windisch W, Schnyder H, Grill E. 2016b Leveraging abscisic acid receptors for efficient water use in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, 6791–6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin XY, Sun ZP, Struik PC, Van der Putten PEL, Van Ieperen W, Harbinson J. 2011. Using a biochemical C4 photosynthesis model and combined gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence measurements to estimate bundle-sheath conductance of maize leaves differing in age and nitrogen content. Plant, Cell and Environment 34, 2183–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.