A cell wall-localized GmPAP1-like protein is up-regulated by Pi starvation, and is involved in extracellular dNTP utilization in soybean.

Keywords: Cell wall proteins, soybean, phosphorus deficiency, phosphorus utilization, proteomics, purple acid phosphatase

Abstract

Plant root cell walls are dynamic systems that serve as the first plant compartment responsive to soil conditions, such as phosphorus (P) deficiency. To date, evidence for the regulation of root cell wall proteins (CWPs) by P deficiency remains sparse. In order to gain a better understanding of the roles played by CWPs in the roots of soybean (Glycine max) in adaptation to P deficiency, we conducted an iTRAQ (isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation) proteomic analysis. A total of 53 CWPs with differential accumulation in response to P deficiency were identified. Subsequent qRT-PCR analysis correlated the accumulation of 21 of the 27 up-regulated proteins, and eight of the 26 down-regulated proteins with corresponding gene expression patterns in response to P deficiency. One up-regulated CWP, purple acid phosphatase 1-like (GmPAP1-like), was functionally characterized. Phaseolus vulgaris transgenic hairy roots overexpressing GmPAP1-like displayed an increase in root-associated acid phosphatase activity. In addition, relative growth and P content were significantly enhanced in GmPAP1-like overexpressing lines compared to control lines when deoxy-ribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) was applied as the sole external P source. Taken together, the results suggest that the modulation of CWPs may regulate complex changes in the root system in response to P deficiency, and that the cell wall-localized GmPAP1-like protein is involved in extracellular dNTP utilization in soybean.

Introduction

Phosphorus (P) is a critical macronutrient in plants that not only serves as a major structural component, but also acts directly and indirectly in multiple metabolic processes, such as membrane and nucleotide synthesis, photosynthesis, energy transmission, and signal transduction (Raghothama, 1999; Vance et al., 2003; Plaxton and Lambers, 2015). Available phosphate (Pi) commonly limits crop production on arable lands worldwide, especially on acid soils (von Uexküll and Mutert 1995; Vance et al. 2003). In nature, plants have developed a set of strategies to enhance P acquisition and utilization efficiency in P-limited soils (Liang et al., 2014). Multiple adaptive strategies to low-P stress have been well documented in roots, including modification of root architecture and morphology, increased root exudation of organic acids and purple acid phosphatase (PAP), and enhanced symbiotic association with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi (Chiou and Lin, 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2014; Plaxton and Lambers, 2015).

In plant roots, cell walls are directly connected to the rhizosphere environment, and are thus the first compartment to perceive and transmit extra- and intercellular signals in many pathways, and to do this they rely on the enzymatic activities of cell wall proteins (CWPs) (Jamet et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2012, 2016; Hoehenwarter et al., 2016). CWPs only account for approximately 10% of cell wall dry mass, and yet they include several hundred proteins acting across wide-ranging functions (Fry, 1988; Cosgrove, 1997; Borderies et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2004; Bayer et al., 2006). CWPs can be divided into three categories according to their binding properties, namely labile proteins that exhibit little or no interaction with other cell wall components, weakly bound proteins that are extractable with salt solutions, and strongly bound proteins that are only released by intensive extraction treatments (Jamet et al., 2006, 2008; Komatsu and Yanagawa, 2013). Although relatively minor in quantity, CWPs are critical for the maintenance of biological functionality in the plant extracellular matrix (Somerville et al., 2004; Bayer et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2006). Using a variety of proteomics techniques, CWPs have been identified in a range of plant species, including Arabidopsis thaliana (Bayer et al., 2006; Minic et al., 2007), Medicago sativa (Soares et al., 2007), chickpea (Cicer arietinum) (Bhushan et al., 2006), maize (Zea mays) (Zhu et al., 2006, 2007), rice (Oryza sativa) (Jung et al., 2008), and sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum) (Calderan-Rodrigues et al., 2014). Despite this, there is a scarcity of proteomics data available for CWP responses to mineral nutrient deficiencies, particularly P deficiency.

In recent years, functional analysis of several Pi starvation-responsive and cell wall-localized proteins has shed light on vital roles of CWPs involved in plant adaptation to P deficiency. For example, nine β-expansin members were identified in soybean (Li et al., 2014), one of which, GmEXPB2, is up-regulated by Pi starvation and appears to play an important role in mediating root growth, suggesting that alteration of cell wall structure is critical for plant adaptation to P deficiency (Guo et al., 2011). Additionally, two cell wall-localized purple acid phosphatases (PAPs), NtPAP12 in tobacco and AtPAP25 in Arabidopsis, are suggested to be involved in cell wall synthesis (Kaida et al., 2008, 2009, 2010; Del Vecchio et al., 2014). Beyond mediation of cell wall biosynthesis, extracellular and cell wall-localized PAPs have also been found to participate in extracellular P scavenging and recycling (Tran et al., 2010a, 2010b; Tian and Liao, 2015). In Arabidopsis, three secreted PAPs (AtPAP10, AtPAP12, and AtPAP26) account for the bulk of the enhanced secreted acid phosphatase activity observed with P deficiency (Hurley et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011, 2014; Robinson et al., 2012). These secreted PAPs possess high activities against a wide range of organic phosphomonoesters, and are suggested to participate in extracellular organic P [e.g. ATP, ADP, and dNTP (deoxy-ribonucleotide triphosphate)] utilization (Hurley et al., 2010; Tran et al., 2010b; Wang et al., 2011, 2014; Robinson et al., 2012). Similar results have also been observed for extracellular PAPs in other plants, including bean (Liang et al., 2010, 2012), rice (Lu et al., 2016), and Stylosanthes (Liu et al., 2016). However, the functions of cell wall-localized PAPs remain largely unknown in soybean and many other crops.

Soybean is an important legume crop that is a valuable source of protein and vegetable oil for human consumption (Herridge et al., 2008). Low Pi availability inhibits soybean growth and production on many soils (Zhao et al., 2004; Ao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010). Although a number of adaptive strategies to Pi starvation have been observed in soybean, along with series of Pi starvation-responsive genes (Tian et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2004; Ao et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2011; Li et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2014), a proteomic-level characterization of soybean root CWPs in low-Pi conditions has yet to be reported. In this study, an iTRAQ (isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation) proteomics assay was conducted with soybean roots to identify water-soluble and weakly bound CWPs that are responsive to Pi starvation. The CWPs that were identified as having differential accumulation were then functionally classified. Finally, a cell wall-localized PAP, GmPAP1-like, was tested for differential expression and participation in extracellular organic-P utilization.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

For low-Pi experiments, the soybean (Glycine max) genotype YC03-3 was grown in hydroponic culture. Seeds were germinated in paper rolls moistened with half-strength nutrient solution after surface-sterilization with 10% (v/v) H2O2 as previously described (Liang et al., 2013). The full-strength nutrient solution without phosphate was composed of (in mM): 1.5 KNO3, 1.2 Ca(NO3)2, 0.4 NHNO3, 0.025 MgCl2, 0.5 MgSO4, 0.3 K2SO4, 0.3 (HN4)2SO4, 0.0015 MnSO4, 0.0015 ZnSO4, 0.0005 CuSO4, 0.00015 (NH4)6Mo7O24, 0.0025 H3BO3, and 0.04 Fe-Na-EDTA. Five days after seed germination, uniform seedlings were transplanted to full-strength nutrient solution containing 5 µM (–P) or 250 µM (+P) KH2PO4. The nutrient solution was continuously aerated and replaced every week. Dry weight and P content were determined 10 d after transplantation for both shoots and roots, together with root length, average diameter, and surface area. Roots were also harvested for extraction of water-soluble and weakly bound CWPs, assays of acid phosphatase (APase) activity, and analysis of gene expression.

For the gene temporal expression assay, soybean seeds were surface-sterilized and germinated as described above. After germination, uniform seedlings were transplanted to –P or +P nutrient solutions. Samples of roots were harvested for RNA extraction at three growth stages, namely seedling (7 d after transplanting), flowering (31 d after transplanting), and maturity (51 d after transplanting). All experiments had four biological replicates.

To assay genotypic variation of gene expression, nine soybean genotypes, contrasting in P-use efficiency were selected: YC03-3, NH89, NH112, ZDD06270, ZDD04072, ZDD12944, ZDD04044, ZDD20323, and ZDD16817 (Zhao et al., 2004). After seed germination, uniform seedlings were grown in the full-strength nutrient solution containing 5 µM (–P) or 250 µM (+P) KH2PO4 as described above. After 10 d, roots were separately harvested for gene expression analysis. All experiments had four biological replicates.

Measurement of plant P content

Plant P content was measured as previously described, with modifications (Murphy and Riley, 1962; Qin et al., 2012). Briefly, about 0.1 g of dry soybean plants or transgenic bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) hairy root samples were ground into powder and digested by boiling with H2SO4 and H2O2. Each supernatant was then transferred to a volumetric flask with the volume adjusted to 100 ml using deionized water. Phosphorus content in the solution was then measured using a Continuous Flow Analytical System (Skalar, Holland) according to the user manual.

Identification of water-soluble and weakly bound cell wall proteins from soybean roots

Proteins weakly bound to the cell wall were extracted from both P-deficient and P-sufficient soybean roots as previously described (Feiz et al., 2006). Briefly, 4 g of soybean roots from each of the four biological replicates were pooled and ground into a homogeneous slurry in a cold-room. The mixture was then centrifuged for 15 min at 1000 g and 4 °C to separate cell walls from soluble cytoplasmic fluid. Pellets were washed with 5 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.6, followed by 0.6 M and then 1 M sucrose, before a final wash with 3 l of 5 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.6. The resulting cell wall fraction was ground into powder in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized prior to protein extraction. Weakly bound proteins were obtained by two extractions with 5 mM acetate buffer containing 0.2 M CaCl2, followed by two extractions with 5 mM acetate buffer containing 2 M LiCl. The products were pooled, desalted using Econo-Pac® 10DG desalting columns (BIO-RAD, USA), lyophilized, and used for the iTRAQ proteomics assay. Briefly, proteins were digested with Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) with a ratio of protein:trypsin of 30:1 at 37 °C for 16 h. After digestion, the peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation. The peptides were reconstituted in 0.5M TEAB (triethyl ammonium bicarbonate) and processed according to the manufacture’s protocol for 8-plex iTRAQ reagent (Applied Biosystems). Briefly, one unit of iTRAQ reagent was thawed and reconstituted in 24 μl isopropanol. Samples were labeled with the iTRAQ tags as follows: protein extracted from P-sufficient roots was labeled with 117-tag and protein extracted from P-deficient roots was labeled with 114-tag following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (iTRAQ® Reagents, USA), and samples were analysed by nanoLC-MS/MS after going through a chromatography separation. Data acquisition was performed with a TripleTOF 5600 System (AB SCIEX, Concord, Canada) fitted with a Nanospray III source (AB SCIEX, Concord, Canada) and a pulled-quartz tip as the emitter (New Objectives, Woburn, USA). Raw data files acquired from the TripleTOF 5600 were converted into MGF files using 5600 msconverter and the MGF files were searched (see Dataset 1 available at Dryad Digital Repository http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6t1f5). Protein identification was performed by using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, version 2.3.02, UK). For protein identification, the charge states of peptides were set to +2 and +3. Specifically, an automatic decoy database search was performed in Mascot by choosing the decoy checkbox in which a random sequence of database was generated and tested for raw spectra as well as the real database. To reduce the probability of false peptide identification, only peptides at the 95% confidence interval according to a Mascot probability analysis were counted as identified. In addition, each confidently identified protein had at least one unique peptide. For protein quantization, it was required that a protein contained at least two unique spectra. The quantitative protein ratios were weighted and normalized using the median ratio in Mascot. Proteins scoring higher than 60, ratios with P-values <0.05 (expectation value), and fold-changes >1.5 were considered as significant.

Secreted proteins with signaling peptides were predicted using the Signal-P V3 program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/) as previously described (Bendtsen et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2006). In addition, the Secretome P 1.0 Server was also used for the prediction of potential CWPs secreted through a non-classic secretion pathway (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP-1.0/) (Bendtsen et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2006).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from soybean roots and transgenic bean hairy roots using the RNA-solve reagent (OMEGA bio-tek, USA). Total RNA was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen, USA) to remove genomic DNA prior the production of reverse-transcripts using MMLV-reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA) following the instructions in the manuals. Synthesized first-strand cDNA was used for SYBR Green-monitored qRT-PCR analysis on a Rotor-Gene 3000 real-time PCR system (Corbett Research, Australia). qRT-PCR primer pairs (Table S3 at Dryad) were designed according to the deduced cDNA sequences of the differentially expressed CWPs. Primer pairs for GmEF-1a (accession no. X56856; 5′-TGCAAAGGAGGCTGCTAACT-3′ and 5′-CAGCATCACCGTTCTTCAAA-3′) and PvEF-1a (accession no. PvTC3216; 5′-TGAACCACCCTGGTCAGATT-3′ and 5′-TCCAGCATCACCATTCTTCA-3′) were used as housekeeping-gene controls to normalize the expression of the corresponding genes in soybean and the expression of GmPAP1-like in transgenic bean hairy roots, respectively.

Assay of APase activity

Internal APase activity was determined using the extracts from soybean roots. Root proteins were extracted and incubated in 45 mM sodium acetate buffer containing 1 mM ρ-nitrophenylphosphate (ρ-NPP) at 35 ℃ for 15 min as previously descried (Liang et al., 2010). The amount of released nitrophenol from ρ-NPP was then quantified by measuring absorbance at 405 nm (A405).

Quantitative and staining analyses of root-associated APase activity were conducted following published protocols (Liu et al., 2016). Briefly, for quantitative analysis, transgenic bean hairy roots were incubated for 20 min in 45 mM Na-acetate buffer containing 2 mM ρ-NPP (pH 5.0). The reaction was terminated by adding 1 ml of 1 M NaOH prior to measuring A405. Root-associated APase activity was expressed as micromoles of ρ-NPP hydrolysed per minute per gram of roots.

For root-associated APase activity staining, soybean roots and transgenic bean hairy roots were placed on solid Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium and covered with 0.5% (w/v) agar containing 0.02% (w/v) of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP; Sigma, USA). After 2 h of incubation at 25 °C, root-associated APase activity was indicated by the intensity of blue color on root surfaces. Images were then captured by a single-lens reflex camera (Canon, Japan).

Isolation and subcellular localization of GmPAP1-like protein

Full-length cDNA of soybean purple acid phosphatase 1-like, GmPAP1-like, was amplified and sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence of the GmPAP1-like protein together with PAP homologues from other plant species were used for phylogenetic tree analysis using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates in the MEGA 5 program.

The primers, 5′-CTCTAGCGCTACCGGTATGATGATGA GTGGGATGG-3′ and 5′-CATGGTGGCGACCGGTGCAGAT GCTAGTGTTGTAGCTGGAC-3′ were used to amplify GmPAP1-like. The PCR product was subsequently cloned into the pEGAD vector to produce a GmPAP1-like-GFP construct. The construct was then transformed into bean hairy roots following published methods (Liang et al., 2010). The pEGAD empty vector with GFP expression driven by a CaMV 35S promoter was used as a control. Cell walls were indicated by propidium iodide (PI) staining (Liang et al., 2010). Green fluorescence derived from GFP and red fluorescence derived from PI were observed by confocal scanning microscopy at 488 nm and 636 nm, respectively (LSM780, Zeiss, Germany).

Functional characterization of GmPAP1-like in bean hairy roots

The full length of GmPAP1-like was then subcloned into the modified pEGAD vector to produce a 35S::GmPAP1-like over-expression construct. Plasmids of the GmPAP1-like over-expression construct and the empty vector were transformed into bean hairy roots as previously described (Liang et al., 2010). Transgenic hairy roots verified by qRT-PCR analysis were then used to analyse root-associated APase activity and the utilization of extracellular dNTPs by GmPAP1-like. The dNTP utilization experiments were conducted as described previously (Liang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016) with minor modifications. Briefly, uniform transgenic bean hairy roots were supplied with either 1.2 mM KH2PO4 or 0.4 mM dNTP in solid MS medium as the sole external P source. Fresh weight and P content of hairy roots were determined 14 d after initiation of the P treatments. Three independent lines were tested with each treatment using four biological replicates.

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed by Student’s t-test using SPSS software (SPSS Institute, USA).

Results

Effects of Pi starvation on soybean biomass and P content

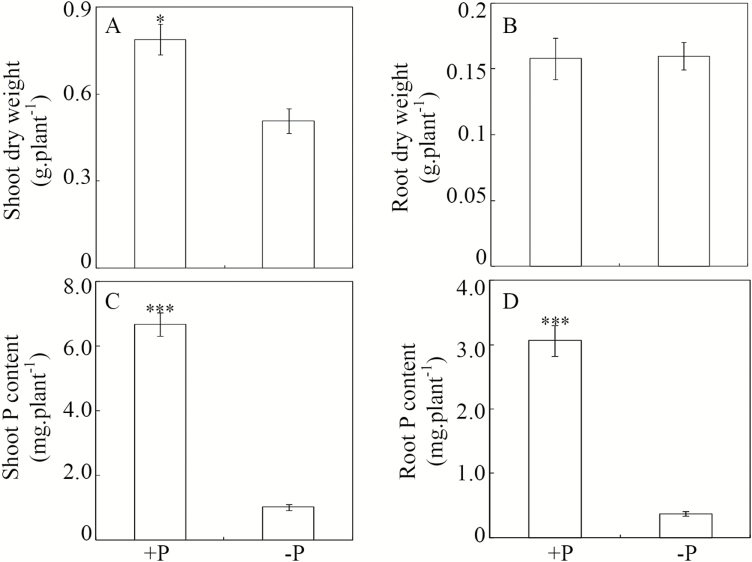

Low P availability significantly affected soybean growth in hydroponic culture, as reflected by decreases in plant dry weight and total P content relative to plants grown in +P solutions (Fig. 1). P-deficient plants exhibited a 35% reduction in shoot dry weight compared with the P-sufficient plants (Fig. 1A). In contrast, no significant difference in root dry weight was observed between the two P treatments (Fig. 1B). Total P content was significantly lower in plants grown under low-P conditions than in those grown under P-sufficient conditions. Total shoot and root P contents were 6.6 and 8.2 times lower, respectively, in P-deficient plants than in P-sufficient plants (Fig. 1C, D).

Fig. 1.

Effects of P availability on soybean dry weight and P content. Soybean seedlings were treated with +P (250 μM KH2PO4) or –P (5 μM KH2PO4). Data are means of four replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two P treatments: *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

Effects of Pi starvation on soybean root morphology

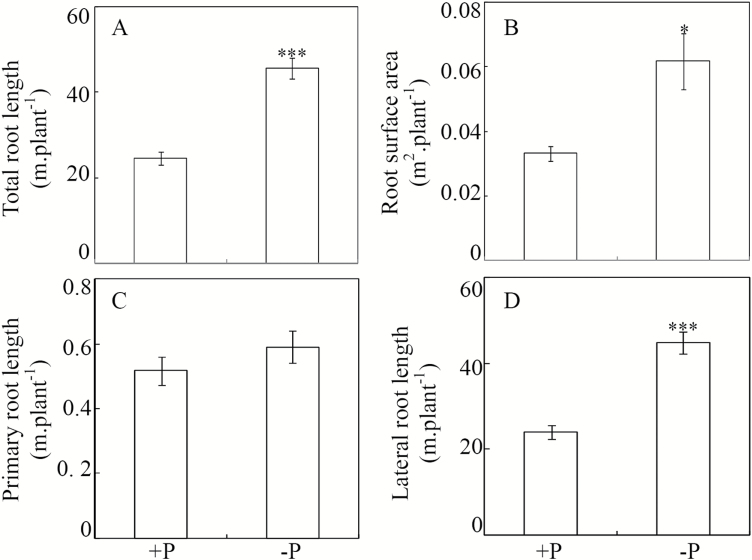

Soybean roots were significantly affected by Pi starvation. Compared to P-sufficient control plants, total root length and surface area were 1.8- and 1.9-fold higher, respectively, in the P-deficient treatment (Fig. 2A, B). Primary root lengths did not vary significantly (Fig. 2C), but lateral root lengths nearly doubled in P-deficient plants relative to P-sufficient plants (Fig. 2D). This suggests that the significant increase in total root length caused by P deficiency was mainly due to enhanced growth of lateral roots. Furthermore, it was observed that the root average diameter at the high-P level was higher than that at the low P-level (Fig. S1 at Dryad), suggesting that Pi starvation resulted in thinner soybean roots.

Fig. 2.

Effects of P availability on soybean root growth. Soybean seedlings were treated with +P (250 μM KH2PO4) or –P (5 μM KH2PO4). Data are means of four replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two P treatments: *P<0.05; ***P<0.001.

Effects of Pi starvation on APase activity in soybean roots

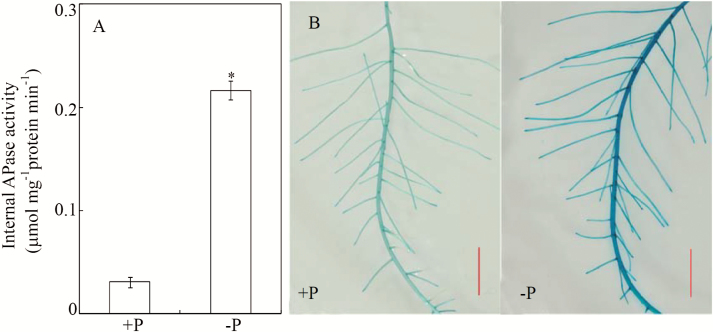

To further characterize the effects of P deficiency on soybean roots, APase activity was investigated at the two P levels. The results showed that APase activity increased with Pi starvation (Fig. 3). Internal APase activity in P-deficient soybean roots was about six times higher than in the P-sufficient roots (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the root-associated APase activity was also enhanced by Pi starvation, as indicated by the higher intensity of blue color derived from BCIP hydrolysis along root surfaces (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effects of P availability on the APase activity of soybean roots. (A) Internal APase activity in soybean roots subjected to +P (250 μM KH2PO4) or –P (5 μM KH2PO4) conditions. Data are means of four replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two P treatments: *P<0.05. (B) APase activity on root surfaces of +P and –P soybean plants detected by BCIP staining. Scale bars are 2 cm.

Identification of Pi starvation-responsive CWPs in soybean roots

Cell wall proteins collected from soybean roots subjected to different P treatments were analysed using the iTRAQ technique. In total, 71 proteins were found to be significantly regulated by Pi starvation, including 30 with enhanced and 41 with suppressed accumulation (Tables S1, S2 at Dryad). Among these 71 differentially accumulated proteins, 53 were predicated as secreted and considered as cell wall-associated proteins according to Signal-P V3 and Secretome P 1.0 Server analysis, including 27 up-regulated and 26 down-regulated proteins, which were classified into six groups according to their potential functions (Table 1). The up-regulated CWPs were classified into the functional groups as follows: carbohydrate metabolism accounted for seven proteins, oxido-reduction for five, protein modification and turnover for three, miscellaneous functions for three, and unknown functions for nine. In the miscellaneous group, two purple acid phosphatases were identified, including purple acid phosphatase 1-like (GmPAP1-like) and purple acid phosphatase 22-like (GmPAP22-like), which respectively exhibited 1.7- and 2.3-fold more accumulation in P-deficient roots than in P-sufficient roots (Table 1).

Table 1.

iTRAQ identification of proteins regulated by Pi starvation and predicted to be CWPs.

| Number | Description | Locus name | Protein accession | Putative function | Fold-change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | |||||

| 1 | Laccase-7-like | Glyma.U027400 | XP_003520942 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 7.0 |

| 2 | Polygalacturonase PG1 precursor | Glyma.19G006200 | NP_001238091 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 6.9 |

| 3 | Polygalacturonase inhibitor 2 precursor | Glyma.08G079100 | XP_003531065 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 5.7 |

| 4 | Probable polygalacturonase isoform X2 | Glyma.08G017300 | XP_003532926 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 3.3 |

| 5 | Probable polygalacturonase | Glyma.09G256100 | XP_003533597 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 1.8 |

| 6 | Dirigent protein 20-related | Glyma.11G150400 | NP_001238114 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 1.7 |

| 7 | Dirigent protein 22-like | Glyma.01G127200 | XP_003516990 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 1.7 |

| 8 | Cationic peroxidase 1-like-1 | Glyma.03G038700 | XP_003522119 | Oxido-reduction | 2.4 |

| 9 | Cationic peroxidase 1-like-2 | Glyma.18G211000 | XP_003552297 | Oxido-reduction | 2.2 |

| 10 | Peroxidase 39-like | Glyma.12G195600 | XP_003540317 | Oxido-reduction | 1.7 |

| 11 | Reticuline oxidase-like protein-like | Glyma.15G134300 | XP_003546286 | Oxido-reduction | 6.2 |

| 12 | Peroxidase A2-like | Glyma.15G129200 | XP_014623798 | Oxido-reduction | 4.6 |

| 13 | Glu S.griseus protease inhibitor | Glyma.20G205800 | XP_003556368 | Protein modification and turnover | 4.3 |

| 14 | Kunitz trypsin protease inhibitor-like precursor | Glyma.16G211700 | NP_001237751 | Protein modification and turnover | 4.2 |

| 15 | Aspartic proteinase nepenthesin-1-like | Glyma.11G157000 | XP_003538263 | Protein modifcation and turnover | 1.8 |

| 16 | Purple acid phosphatase 1-like | Glyma.08G291600 | XP_003532035 | Miscellaneous protein | 1.7 |

| 17 | Purple acid phosphatase 22-like | Glyma.10G071000 | XP_003537064 | Miscellaneous protein | 2.3 |

| 18 | Nuclease S1-like | Glyma.01G083300 | XP_003516835 | Miscellaneous protein | 4.9 |

| 19 | Polyvinylalcohol dehydrogenase-like | Glyma.09G239900 | XP_006587758 | Unknown | 3.5 |

| 20 | Clathrin light chain 1-like | Glyma.15G072100 | XP_003545895 | Unknown | 2.4 |

| 21 | AIR12 precursor | Glyma.03G088900 | NP_001237825 | Unknown | 2.1 |

| 22 | Early nodulin-like protein | Glyma.06G061200 | NP_001235764 | Unknown | 1.8 |

| 23 | Vacuolar-sorting receptor 1-like isoform 1 | Glyma.01G242800 | XP_003517598 | Unknown | 1.6 |

| 24 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.15G131400 | XP_014623068 | Unknown | 4.7 |

| 25 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.09G025200 | XP_003534773 | Unknown | 3 |

| 26 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.02G154700 | XP_003520231 | Unknown | 2.3 |

| 27 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.11G150300 | NP_001238117 | Unknown | 2.0 |

| Down-regulated | |||||

| 1 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase-like | Glyma.18G291500 | XP_003552703 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.3 |

| 2 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase, basic isoform-like | Glyma.15G142400 | XP_003546326 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.5 |

| 3 | Germin-like protein 3 | Glyma.16G060900 | NP_001236994 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.3 |

| 4 | Germin-like protein subfamily 1 member 7 | Glyma.19G086000 | XP_003547666 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.5 |

| 5 | NADH dehydrogenase | Glyma.20G108500 | NP_001235228 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.1 |

| 6 | Extensin-like protein-like | Glyma.13G178700 | XP_003528459 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.3 |

| 7 | Polygalacturonase inhibitor-like | Glyma.19G145200 | XP_003554195 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.7 |

| 8 | Alpha-xylosidase-like | Glyma.01G081300 | XP_003516826 | Carbohydrate metabolism | 0.5 |

| 9 | Peroxidase 16-like-1 | Glyma.09G057100 | XP_003533723 | Oxido-reduction | 0.4 |

| 10 | Peroxidase 16-like-2 | Glyma.13G098400 | XP_003543742 | Oxido-reduction | 0.5 |

| 11 | Peroxidase 3-like | Glyma.03G208200 | XP_003520731 | Oxido-reduction | 0.6 |

| 12 | Copper amino oxidase precursor | Glyma.17G019300 | NP_001237211 | Oxido-reduction | 0.6 |

| 13 | Serine carboxypeptidase-like | Glyma.09G226700 | XP_003534383 | Protein modification and turnover | 0.2 |

| 14 | Subtilisin-like protease | Glyma.12G031800 | XP_003540860 | Protein modification and turnover | 0.4 |

| 15 | Aspartic proteinase nepenthesin-1-like | Glyma.08G321200 | XP_003530761 | Protein modification and turnover | 0.6 |

| 16 | Agamous-like MADS-box protein AGL8-like | Glyma.13G052100 | XP_003544014 | Signal transduction | 0.4 |

| 17 | Acyl CoA binding protein | Glyma.09G214500 | NP_001237529 | Miscellaneous protein | 0.6 |

| 18 | Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase precursor | Glyma.13G267900 | NP_001235549 | Miscellaneous protein | 0.6 |

| 19 | Bark storage protein A isoform X1 | Glyma.07G083900 | XP_003528930 | Miscellaneous protein | 0.6 |

| 20 | Osmotin-like protein-like | Glyma.12G064300 | XP_003539684 | Unkown | 0.2 |

| 21 | Programmed cell death protein 5-like | Glyma.08G082100 | XP_003524788 | Unkown | 0.4 |

| 22 | Polyadenylate-binding protein 2-like | Glyma.02G103900 | XP_003518706 | Unkown | 0.5 |

| 23 | Protein EXORDIUM-like | Glyma.04G100400 | XP_003522788 | Unkown | 0.6 |

| 24 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.11G048100 | NP_001239639 | Unkown | 0.5 |

| 25 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.10G090100 | NP_001239749 | Unkown | 0.5 |

| 26 | Uncharacterized protein | Glyma.06G319500 | XP_003526379 | Unkown | 0.6 |

The down-regulated proteins separated into the functional groups as follows: carbohydrate metabolism accounted for eight proteins, oxido-reduction for four, protein modification and turnover for three, signal transduction for one, miscellaneous functions for three, and unknown functions for seven (Table 1).

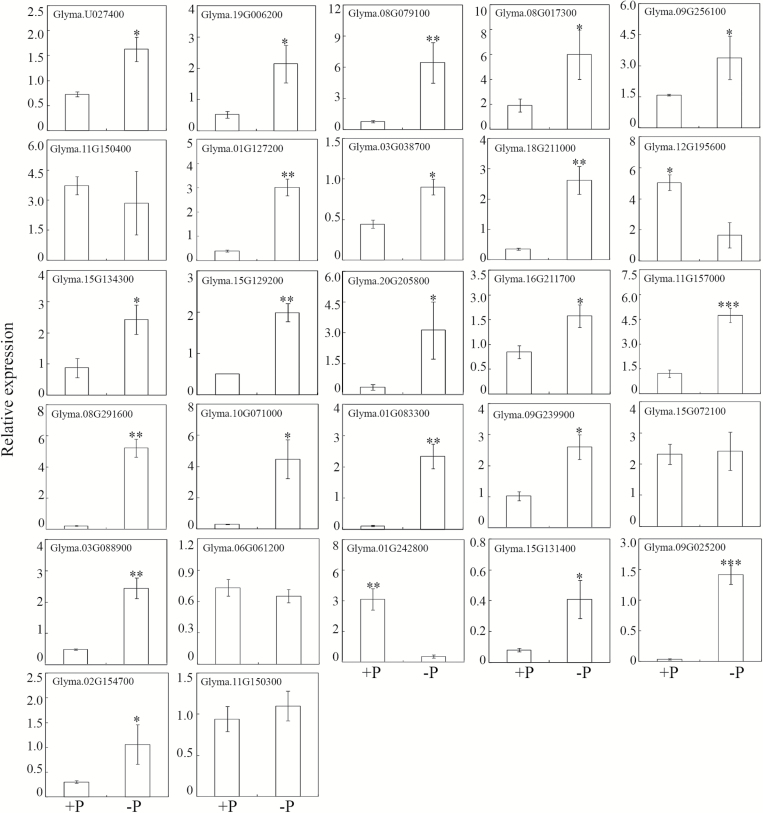

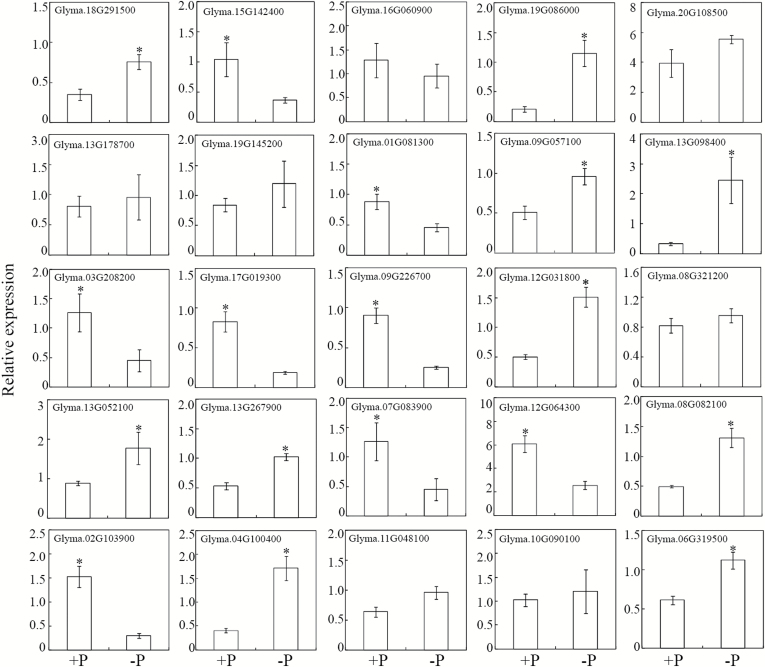

Expression patterns of corresponding genes encoding CWPs in response to Pi starvation

The transcriptional levels of genes encoding all the 53 differentially accumulated CWPs were analysed through qRT-PCR, except for the Acyl CoA binding protein (accession number NP_001237529), since no specific PCR primers could be designed to detect its expression. Consistent with the protein accumulation patterns, the transcription levels of 21 genes encoding Pi-starvation up-regulated proteins were significantly increased by P deficiency in soybean roots (Fig. 4). Among them, the transcription of GmPAP1-like and GmPAP22-like increased by 25- and 9-fold, respectively, in response to P deficiency. Of the remaining up-regulated CWPs, the transcription of four genes was not affected by Pi starvation, and the transcription of two genes was down-regulated (Fig. 4). For down-regulated proteins, the transcription levels of only eight corresponding genes were suppressed, while transcription of seven corresponding genes was not affected, and ten were even up-regulated by Pi starvation (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Transcription levels of genes encoding Pi-starvation up-regulated CWPs. qRT-PCR was conducted to analyse gene expression in roots subjected to +P (250 μM KH2PO4) or –P (5 μM KH2PO4) treatments. Data are means of four independent replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two P treatments: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Fig. 5.

Transcription levels of genes encoding Pi-starvation down-regulated CWPs. qRT-PCR was conducted to analyse gene expression in roots subjected to +P (250 μM KH2PO4) or –P (5 μM KH2PO4) treatments. Data are means of four independent replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the two P treatments: *P<0.05.

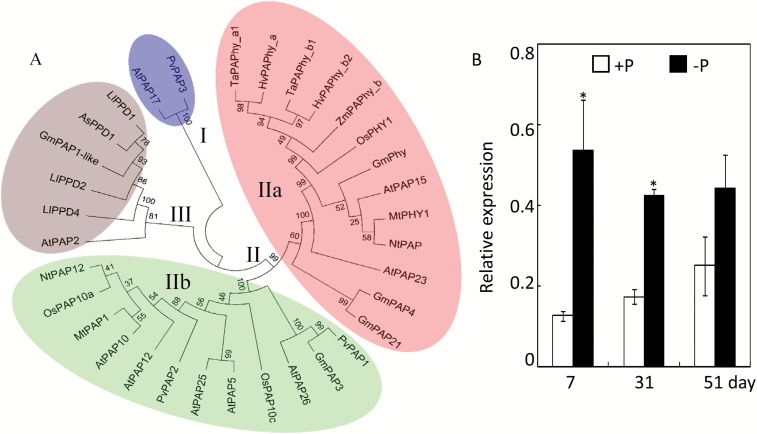

Phylogenetic analysis and expression patterns of GmPAP1-like

A phylogenetic tree of GmPAP1-like, GmPAP22-like, and 32 other PAPs with known functions was constructed based on amino acid sequences. The phylogenetic tree showed that the PAPs could be classified into three distinct clades (I–III; Fig. 6A). Clade I consisted of two PAPs, AtPAP17 and PvPAP3. Clade II was further divided into two subgroups (IIa and IIb), with GmPAP22-like (also reported as GmPAP21) together with other PAPs identified as phytases falling into clade IIa. GmPAP1-like clustered with AtPAP2, three diphosphonucleotide phosphatase/phosphodiesterase (PPD) proteins from white lupin (LjPPD1/2/4), and one PPD from Astragalus sinicus (AsPPD1) to form clade III. This clustering indicates that GmPAP1-like belongs to the PPD subfamily of plant PAPs (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic analysis and expression patterns of GmPAP1-like. (A) Phylogenetic analysis of soybean GmPAP1-like and GmPAP22-like (also named as GmPAP21) with other plant PAPs. The first two letters of each PAP protein label represent the abbreviated species name: As, Astragalus sinicus; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Gm, Glycine max; Hv, Hordeum vulgare; Ll, Lupinus luteus; Mt, Medicago truncatula; Nt, Nicotiana tabacum; Os, Oryza sativa; Pv, Phaseolus vulgaris; Ta, Triticum aestivum; Zm, Zea mays. The numerals I, II, and III designate the three groups of PAP proteins. Group II was further divided into two subgroups (IIa and IIb). Bootstrap values (%) are indicated for major branches. (B) Expression patterns of soybean GmPAP1-like in response to Pi starvation at different growth stages. *P<0.05. (This figure is available in color at JXB online.)

Since GmPAP22-like has recently been suggested to be involved in soybean nodule growth (Li et al., 2017), GmPAP1-like was further selected and characterized to test for functions in soybean root adaptation to Pi starvation. Expression patterns of GmPAP1-like were investigated at different growth stages in soybean roots at the two P levels. The results showed that expression increased significantly in response to Pi starvation in both seedlings and flowering plants (Fig. 6B), as indicated by 5- and 2.5-fold increases in transcription, respectively, in –P compared to +P treatments. In contrast, there was no significant difference for GmPAP1-like expression between the two P treatments at the maturity stage. In addition, the expression of GmPAP1-like in response to Pi starvation was also investigated in nine other soybean genotypes. After 10 d of low-P treatment the transcripts of GmPAP1-like in the roots of all the genotypes were markedly up-regulated by Pi starvation (Fig S2 at Dryad). In contrast, no genotypic differences were observed under P-deficient conditions.

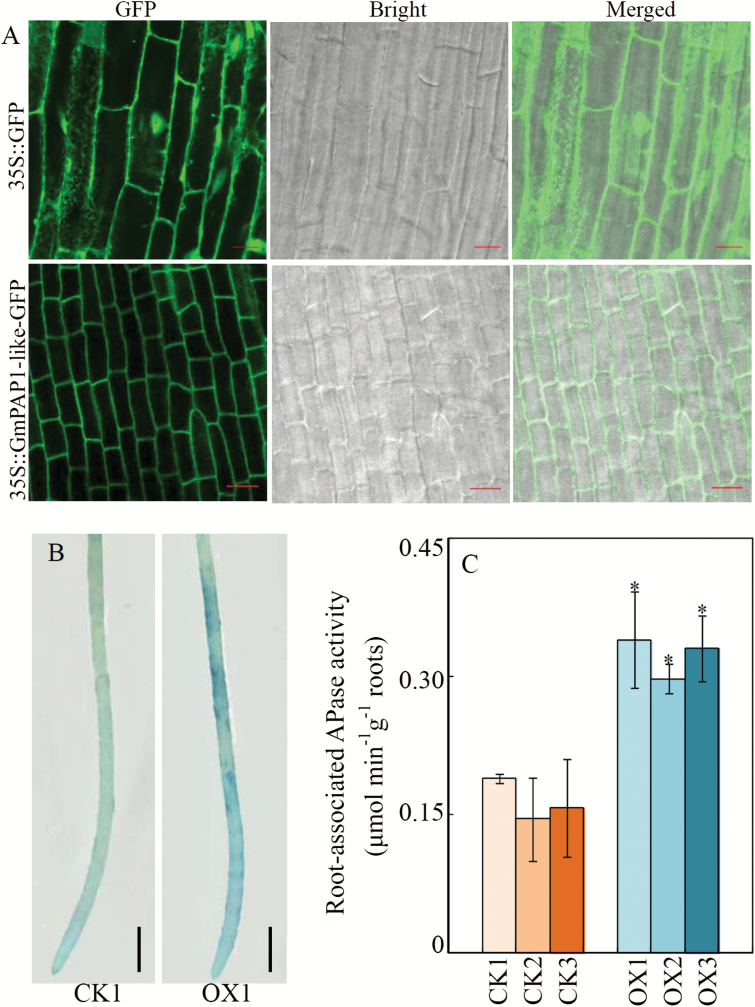

Contribution of cell wall-localized GmPAP1-like to the enhanced APase activity in transgenic bean hairy roots

To further test whether GmPAP1-like is a cell wall-localized protein, GmPAP1-like was fused with GFP and overexpressed in bean hairy roots. Compared with the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of GFP in the empty-vector control, the green fluorescence of GmPAP1-like-GFP was predominantly detected on the cell periphery (Fig. 7A; Fig. S3 at Dryad), and it merged with the red fluorescence derived from PI staining, strongly suggesting that GmPAP1-like is localized in cell walls.

Fig. 7.

Subcellular localization of GmPAP1-like and root-associated APase activity in transgenic bean hairy roots overexpressing GmPAP1-like. (A) Bean hairy roots expressing 35S::GFP (top row) and 35S:: GmPAP1-like-GFP (bottom row) were observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Scale bars are 20 μm; (B) Root-associated APase activity of bean hairy roots transformed with the empty vector (CK1) or GmPAP1-like (OX1) detected by BCIP staining. Scale bars are 5 mm. (C) Root-associated APase activity of transgenic bean hairy roots. CK1, CK2, and CK3 represent three transgenic hairy root lines transformed with the empty vector; OX1, OX2, and OX3 indicate three transgenic hairy root lines with GmPAP1-like overexpression. Data are means of four biological replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between GmPAP1-like overexpression lines and CK lines: *P<0.05.

Root-associated APase activity was also determined in bean hairy roots with GmPAP1-like overexpression in vivo. The results showed that GmPAP1-like overexpression significantly enhanced root-associated APase activity, as indicated by the development of darker BCIP staining on the surfaces of GmPAP1-like over-expressing hairy roots (Fig. 7B). Consistent with the staining, root-associated APase activity measured using ρ-NPP as the substrate was 2.1-, 1.8-, and 2.0-fold higher for three GmPAP1-like over-expression lines compared with the empty-vector controls (Fig. 7C).

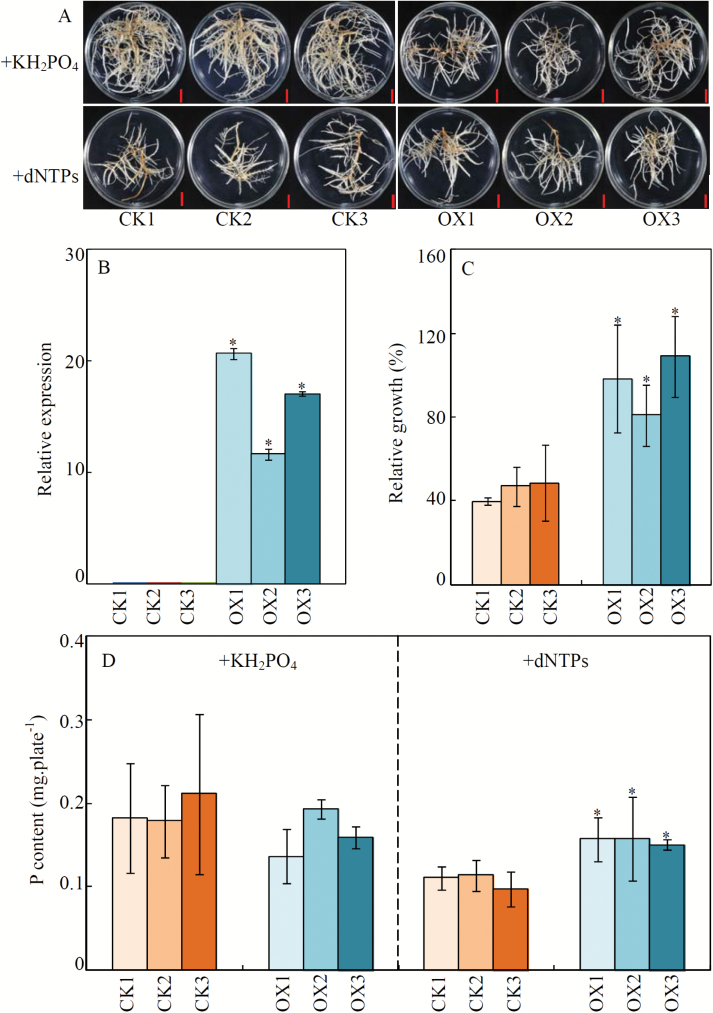

Overexpression of GmPAP1-like enhances extracellular dNTP utilization

To investigate the potential function of GmPAP1-like in relation to organic-P utilization, transgenic bean hairy roots overexpressing GmPAP1-like were generated and confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8B). Uniform transgenic lines were then supplied with one of two P sources, either KH2PO4 or dNTP, for 2 weeks. The results showed that when dNTP was supplied as the sole P source, the fresh weight of control lines (CK) was significantly lower than that observed when KH2PO4 was the P source (Fig. 8A; Fig. S4 at Dryad). The fresh weight of all three GmPAP1-like overexpression lines (OX) did not vary between KH2PO4 and dNTP treatments, which thereby resulted in a higher relative growth with dNTP for the OX lines than for the CK lines (Fig. 8A, C; Fig. S4 at Dryad).

Fig. 8.

Growth and P content of transgenic bean hairy roots supplied with different P sources. (A) Phenotypes of transgenic bean hairy roots supplied with different P sources. Scale bars are 1 cm. (B) Expression levels of GmPAP1-like in transgenic been hairy roots. (C) Relative growth of transgenic bean hairy roots. Relative growth (%) = 100×(Increase of fresh weight in dNTP / Increase of fresh weight in KH2PO4). (D) P content in transgenic bean hairy roots. Uniform transgenic bean hairy roots were grown on MS medium supplied with 1.2 mM KH2PO4 or 0.4 mM dNTP for 14 d. Fresh weight and P content were measured, and the fresh weight was further used for the calculation of relative growth of the roots. CK1, CK2, and CK3 are three transgenic lines transformed with an empty vector; OX1, OX2, and OX3 represent transgenic lines with GmPAP1-like overexpression. Data are means of four biological replicates ±SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences between GmPAP1-like overexpression lines and CK lines: *P<0.05.

Consistent with the observed effects of P source on relative growth, P contents in the dNTP treatment were 46%, 47%, and 40% higher in the three OX lines compared with the CK lines (Fig. 8D). On the other hand, the P content was similar between the OX and CK lines when KH2PO4 was supplied as the sole source of P (Fig. 8D). These results suggest that GmPAP1-like participates in extracellular dNTP utilization in soybean.

Discussion

Low Pi availability is one of the primary factors limiting plant growth on many soils. Over time, plants have evolved many adaptations to maintain growth in low-P soils, including alteration of root morphology and increased exudation of APase, both of which might involve modifications in root cell walls (Cassab and Varner, 1988; Kaplan and Hagemann, 1991; Chiou and Lin, 2011; Liang et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2016a). Cell wall modifications are continuously controlled by the enzymatic actions of CWPs, which account for about 10% of the cell wall dry weight (Cassab, 1998). It is therefore important to study the regulation of CWP accumulation by low-P stress, as well as to determine how this might underlie the physiological and morphological adaptations of plant roots to Pi starvation.

Various methods have been applied to extract CWPs, which can be loosely or tightly bound to the cell wall matrix in higher plants, green alga, and fungi (Fry, 1988; Pardo et al., 2000; Chivasa et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Watson et al., 2004; Feiz et al., 2006; Jung et al., 2008; Calderan-Rodrigues et al., 2014). Among the various methodologies, those developed by Feiz et al. (2006) are considered to be optimum for the extraction of water-soluble and weakly bound plant CWPs, with yields that include up to 73% of the proteins identified as potential CWPs (Feiz et al., 2006). Following these methods, CWPs were extracted from both P-sufficient and P-deficient soybean roots and yielded a total of 71 proteins regulated by Pi starvation (Tables S1 and S2 at Dryad). Moreover, 53 of the 71 differentially expressed proteins (74.6%) were implicated as potential CWPs by SignalP and Secretome analyses (Table 1). The identification of these root CWPs with differential accumulation strongly suggests the presence of complex strategies for remodeling root cell walls in adaptive responses to P deficiency.

The CWPs with differential accumulation in response to P deficiency fell into six functional groups, namely carbohydrate metabolism, oxido-reduction, protein modification and turnover, miscellaneous proteins, signal transduction, and unknown (Table 1). Among the proteins in the carbohydrate metabolism category, three polygalacturonases were found to be up-regulated. Polygalacturonase orthologues have been reported to function as pectin-digesting enzymes in a wide range of developmental processes, such as cell separation, fruit ripening, and cell growth in many plant species (Hadfield and Bennett, 1998; Torki et al., 1999; Daher and Braybrook, 2015). A recent study showed that overexpressing a polygalacturonase gene, PGX1, resulted in enhanced hypocotyl elongation (Xiao et al., 2014). On the other hand, mutation of an exo-polygalacturonase gene, NIMNA, caused cell elongation defects in the early embryo, and markedly reduced suspensor length in Arabidopsis (Babu et al., 2013). Hence we suggest that the polygalacturonases identified in the present study might play similar roles in cell wall loosening, thus enabling the enhanced elongation of soybean roots under P-deficiency (Fig. 2). Other proteins in the carbohydrate metabolism category, such as dirigent-like protein, beta-glucosidase, and extensin-like protein, have been well documented as functioning in the biosynthesis and differentiation of cell walls in other plant species (Davin and Lewis, 2000; Baiya et al., 2014; Draeger et al., 2015). Placing our current results in the context of previous reports suggests that soybean root cell walls undergo complex modifications mediated through changes in abundance of CWPs in response to low-P stress.

Another large group of P-responsive CWPs appears to participate in the metabolism of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Table 1). The dynamics of ROS in plant cell walls has been considered to play direct roles in cell wall loosening via polysaccharide cleavage (Fry, 1998; Fry et al., 2001; Liszkay et al., 2003), thereby affecting cell extension and growth (Rodriguez et al., 2002; Liszkay et al., 2004; Chacón-López et al., 2011). Furthermore, ROS production has recently been reported to be spatially and temporally regulated by Pi starvation in Arabidopsis, which subsequently affects the meristem exhaustion process triggered by Pi-starvation (Tyburski et al., 2009; Chacón-López et al., 2011). Hence the proteins identified in this study as functioning in oxido-reduction might be involved in the processes of cell wall stiffening/loosening through precise regulation of local ROS concentrations, which thus regulates soybean root growth under P-deficient conditions (Fig. 2).

The CWPs identified as functioning in signal transduction, protein modification and turnover, miscellaneous functioning, and unknown functions further reflect the complexity of cell wall modifications associated with soybean adaptation to low-P stress. The agamous-like MADS-box proteins, for example, have been reported to be involved in root development and nutrient-deficiency responses in a wide range of plants, including Arabidopsis, rice and orange (Zhang and Forde, 1998; Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2000; Burgeff et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2016b). Moreover, subtilisin-like proteases have also been suggested to function in the modulation of plant morphology in Arabidopsis, with reported roles in epidermal development for ALE1 (Tanaka et al., 2001), lateral root formation for AIR3 (Neuteboom et al., 1999), and xylem development for XSP1 (Zhao et al., 2000). In the current study, therefore, the subtilisin-like protease and agamous-like MADS-box protein identified as P-responsive CWPs might have roles in regulating soybean root development and growth in response to P deficiency. Other proteins, such as acyl-CoA-binding protein and EXORDIUM-like, might also be associated with development and phytohormone-regulated root growth, respectively (Coll-Garcia et al., 2004; Du et al., 2016). However, elucidation of their exact functions in soybean root responses to Pi starvation will require further investigation.

We found that soybean root-associated APase activity significantly increased with Pi starvation (Fig. 3). Further analysis identified two PAPs, GmPAP22-like and GmPAP1-like, in the CWP fraction with enhanced transcription and protein accumulation in response to low-P stress (Table1, Fig. 4). It is well documented that increased root-associated APase activity in response to Pi-starvation is conserved among diverse plant species (Asmar et al., 1995; George et al., 2008; Tian and Liao, 2015). These responses have been correlated with increased transcription and post-transcriptional modification of PAPs (Robinson et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2016). Placing our current expression and APase activity results in the context of previous reports, it is reasonable to suggest that GmPAP22-like and GmPAP1-like contribute significantly to the increased root-associated APase activity observed in soybean in response to low-P stress.

GmPAP22-like, which is also named GmPAP21, has been suggested to function in P recycling and metabolism in soybean (Li et al., 2012, 2017). In contrast, little information is available on the functional characterization of GmPAP1-like in soybean, and hence it was chosen for more detailed analysis. The phylogenetic tree showed that GmPAP1-like had high similarity and clustered with PPDs, such as AsPPD1 in Astragalus sinicus and LlPPD1 in Lupinus luteus (Fig. 6A). The PPD proteins have been characterized as a subfamily of PAPs, with differences from typical PAPs in certain features (Olczak et al., 2000, 2009).

The limited information available suggests that the PPDs identified to date have divergent functions and are not directly involved in plant adaptations to P deficiency. For example, AsPPD1 from A. sinicus plays a role in controlling the symbiotic ADP levels (Wang et al., 2015), while AtPAP2 in Arabidopsis has been found to modulate carbon metabolism in plastids and mitochondria (Sun et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). In the present study, it was found that GmPAP1-like overexpression in bean hairy roots significantly increased dNTP utilization efficiency, as indicated by higher P content and relative growth of overexpressing lines compared to control lines (Fig. 8C, D). Utilization of nucleic acid P has been reported for a variety of plant PAPs, including PvPAP1 in bean, OsPAP10a in rice, AtPAP12 and AtPAP26 in Arabidopsis, and SgPAP7, SgPAP10, and SgPAP26 in stylo (Liang et al., 2012; Robinson et al., 2012; Tian et al., 2012; Tian and Liao, 2015; Liu et al., 2016). Therefore, GmPAP1-like might play a role in soybean P nutrition by facilitating Pi acquisition from organic P sources, which is similar in functionality to typical PAPs. However, the fresh weights of GmPAP1-like overexpression bean hairy roots were lower than those of control lines under normal conditions (Fig. S4 at Dryad). This is consistent with the observation that overexpression of GmPAP21 inhibits growth in soybean (Li et al., 2017). Taken together, the results suggest that PAP might also affect internal P-derivative metabolism, and thus influences plant growth, which merits further investigation for other roles of GmPAP1-like.

In summary, it is well known that P efficiency in plants is largely determined by root morphology and architecture, which are affected by root cell wall modification and metabolism that rely on the enzymatic activities of CWPs. However, there is a lack of proteomics data available for CWP responses to P deficiency, which is vital to further understand molecular mechanisms underlying root adaptations to P deficiency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify CWPs responsive to Pi starvation in plants through proteomics analysis. Our results strongly suggest that CWPs with diverse functions participate in complex modifications of root cell walls in soybean responses to P deficiency. Among the CWPs that have been identified, a cell wall-localized purple acid phosphatase, GmPAP1-like, contributes to the enhanced root-associated APase activity in response to Pi starvation and is involved in the acquisition of Pi from extracellular dNTPs.

Data deposition

The following data are available at Dryad Data Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6t1f5.

Dataset 1. Mass spectrometry/spectra information for the iTRAQ analysis of soybean cell wall proteins.

Table S1. General information for the 41 proteins with abundance down-regulated in response to low-P stress.

Table S2. General information for the 30 proteins with abundance up-regulated in response to low-P stress.

Table S3. Primer pairs for qRT-PCR analysis of corresponding genes responsive to Pi starvation.

Fig. S1. Phenotype and average root diameter of soybean subjected to P-sufficient and P-deficient conditions.

Fig. S2. Expression patterns of GmPAP1-like in response to Pi starvation among different soybean genotypes.

Fig. S3. Subcellular localization of GmPAP1-like in transgenic bean hairy roots overexpressing GmPAP1-like.

Fig. S4. Effects of overexpression of GmPAP1-like on the growth of transgenic bean hairy roots.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672220 and 31422046), the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0100700), Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars (2015A030306034), Guangdong High-level Personnel of Special Support Program (2015TQ01N078, 2015TX01N042, and YQ201530) and Research Team Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016A030312009). The authors thank Dr Thomas Walk for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Alvarez-Buylla ER, Liljegren SJ, Pelaz S, Gold SE, Burgeff C, Ditta GS, Vergara-Silva F, Yanofsky MF. 2000. MADS-box gene evolution beyond flowers: expression in pollen, endosperm, guard cells, roots and trichomes. The Plant Journal 24, 457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao JH, Fu JB, Tian J, Yan XL, Liao H. 2010. Genetic variability for root morph-architecture traits and root growth dynamics as related to phosphorus efficiency in soybean. Functional Plant Biology 37, 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Asmar F, Gahoonia T, Nielsen NE. 1995. Barley genotypes differ in activity of soluble extracellular phosphatase and depletion of organic phosphorus in the rhizosphere soil. Plant and Soil 172, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Babu Y, Musielak T, Henschen A, Bayer M. 2013. Suspensor length determines developmental progression of the embryo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 162, 1448–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiya S, Hua Y, Ekkhara W, Ketudat Cairns JR. 2014. Expression and enzymatic properties of rice (Oryza sativa L.) monolignol β-glucosidases. Plant Science 227, 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer EM, Bottrill AR, Walshaw J, Vigouroux M, Naldrett MJ, Thomas CL, Maule AJ. 2006. Arabidopsis cell wall proteome defined using multidimensional protein identification technology. Proteomics 6, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen JD, Jensen LJ, Blom N, Von Heijne G, Brunak S. 2004. Feature-based prediction of non-classical and leaderless protein secretion. Protein Engineering, Design & Selection 17, 349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan D, Pandey A, Chattopadhyay A, Choudhary MK, Chakraborty S, Datta A, Chakraborty N. 2006. Extracellular matrix proteome of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) illustrates pathway abundance, novel protein functions and evolutionary perspect. Journal of Proteome Research 5, 1711–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borderies G, Jamet E, Lafitte C, Rossignol M, Jauneau A, Boudart G, Monsarrat B, Esquerré-Tugayé MT, Boudet A, Pont-Lezica R. 2003. Proteomics of loosely bound cell wall proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana cell suspension cultures: a critical analysis. Electrophoresis 24, 3421–3432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgeff C, Liljegren SJ, Tapia-López R, Yanofsky MF, Alvarez-Buylla ER. 2002. MADS-box gene expression in lateral primordia, meristems and differentiated tissues of Arabidopsis thaliana roots. Planta 214, 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderan-Rodrigues MJ, Jamet E, Bonassi MB, Guidetti-Gonzalez S, Begossi AC, Setem LV, Franceschini LM, Fonseca JG, Labate CA. 2014. Cell wall proteomics of sugarcane cell suspension cultures. Proteomics 14, 738–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassab GI. 1998. Plant cell wall proteins. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 49, 281–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassab GI, Varner JE. 1988. Cell wall proteins. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 39, 321–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón-López A, Ibarra-Laclette E, Sánchez-Calderón L, Gutiérrez-Alanis D, Herrera-Estrella L. 2011. Global expression pattern comparison between low phosphorus insensitive 4 and WT Arabidopsis reveals an important role of reactive oxygen species and jasmonic acid in the root tip response to phosphate starvation. Plant Signaling & Behavior 6, 382–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou TJ, Lin SI. 2011. Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 62, 185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivasa S, Ndimba BK, Simon WJ, Robertson D, Yu XL, Knox JP, Bolwell P, Slabas AR. 2002. Proteomic analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana cell wall. Electrophoresis 23, 1754–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll-Garcia D, Mazuch J, Altmann T, Müssig C. 2004. EXORDIUM regulates brassinosteroid-responsive genes. FEBS Letters 563, 82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosgrove DJ. 1997. Assembly and enlargement of the primary cell wall in plants. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 13, 171–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher FB, Braybrook SA. 2015. How to let go: pectin and plant cell adhesion. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davin LB, Lewis NG. 2000. Dirigent proteins and dirigent sites explain the mystery of specificity of radical precursor coupling in lignan and lignin biosynthesis. Plant Physiology 123, 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio HA, Ying S, Park J, Knowles VL, Kanno S, Tanoi K, She YM, Plaxton WC. 2014. The cell wall-targeted purple acid phosphatase AtPAP25 is critical for acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana to nutritional phosphorus deprivation. The Plant Journal 80, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draeger C, Ndinyanka Fabrice T, Gineau E, et al. . 2015. Arabidopsis leucine-rich repeat extensin (LRX) proteins modify cell wall composition and influence plant growth. BMC Plant Biology 15, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du ZY, Arias T, Meng W, Chye ML. 2016. Plant acyl-CoA-binding proteins: an emerging family involved in plant development and stress responses. Progress in Lipid Research 63, 165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiz L, Irshad M, Pont-Lezica RF, Canut H, Jamet E. 2006. Evaluation of cell wall preparations for proteomics: a new procedure for purifying cell walls from Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Plant Methods 2, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 1988. The growing plant cell wall: chemical and metabolic analysis. Harlow, UK: Longman Scientific & Technical. [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC. 1998. Oxidative scission of plant cell wall polysaccharides by ascorbate-induced hydroxyl radicals. The Biochemical Journal 332, 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry SC, Dumville JC, Miller JG. 2001. Fingerprinting of polysaccharides attacked by hydroxyl radicals in vitro and in the cell walls of ripening pear fruit. The Biochemical Journal 357, 729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TS, Gregory PJ, Hocking P, Richardson AE. 2008. Variation in root-associated phosphatase activities in wheat contributes to the utilization of organic P substrates in vitro, but does not explain differences in the P-nutrition of plants when grown in soils. Environmental and Experimental Botany 64, 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Zhao J, Li X, Qin L, Yan X, Liao H. 2011. A soybean β-expansin gene GmEXPB2 intrinsically involved in root system architecture responses to abiotic stresses. The Plant Journal 66, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield KA, Bennett AB. 1998. Polygalacturonases: many genes in search of a function. Plant Physiology 117, 337–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herridge DF, Peoples MB, Boddey RM. 2008. Global inputs of biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural systems. Plant and Soil 311, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehenwarter W, Mönchgesang S, Neumann S, Majovsky P, Abel S, Müller J. 2016. Comparative expression profiling reveals a role of the root apoplast in local phosphate response. BMC Plant Biology 16, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley BA, Tran HT, Marty NJ, Park J, Snedden WA, Mullen RT, Plaxton WC. 2010. The dual-targeted purple acid phosphatase isozyme AtPAP26 is essential for efficient acclimation of Arabidopsis to nutritional phosphate deprivation. Plant Physiology 153, 1112–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamet E, Albenne C, Boudart G, Irshad M, Canut H, Pont-Lezica R. 2008. Recent advances in plant cell wall proteomics. Proteomics 8, 893–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamet E, Canut H, Boudart G, Pont-Lezica RF. 2006. Cell wall proteins: a new insight through proteomics. Trends in Plant Science 11, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YH, Jeong SH, Kim SH, Singh R, Lee JE, Cho YS, Agrawal GK, Rakwal R, Jwa NS. 2008. Systematic secretome analyses of rice leaf and seed callus suspension-cultured cells: workflow development and establishment of high-density two-dimensional gel reference maps. Journal of Proteome Research 7, 5187–5210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida R, Hayashi T, Kaneko TS. 2008. Purple acid phosphatase in the walls of tobacco cells. Phytochemistry 69, 2546–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida R, Satoh Y, Bulone V, Yamada Y, Kaku T, Hayashi T, Kaneko TS. 2009. Activation of beta-glucan synthases by wall-bound purple acid phosphatase in tobacco cells. Plant Physiology 150, 1822–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida R, Serada S, Norioka N, Norioka S, Neumetzler L, Pauly M, Sampedro J, Zarra I, Hayashi T, Kaneko TS. 2010. Potential role for purple acid phosphatase in the dephosphorylation of wall proteins in tobacco cells. Plant Physiology 153, 603–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan DR, Hagemann W. 1991. The relationship of cell and organism in vascular plants. BioScience 41, 693–703. [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu S, Yanagawa Y. 2013. Cell wall proteomics of crops. Frontiers in Plant Science 4, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Saravanan RS, Damasceno CM, Yamane H, Kim BD, Rose JK. 2004. Digging deeper into the plant cell wall proteome. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 42, 979–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Gui S, Yang T, Walk T, Wang X, Liao H. 2012. Identification of soybean purple acid phosphatase genes and their expression responses to phosphorus availability and symbiosis. Annals of Botany 109, 275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li C, Zhang H, Liao H, Wang X. 2017. The purple acid phosphatase GmPAP21 enhances internal phosphorus utilization and possibly plays a role in symbiosis with rhizobia in soybean. Physiologia Plantarum 159, 215–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhao J, Walk TC, Liao H. 2014. Characterization of soybean β-expansin genes and their expression responses to symbiosis, nutrient deficiency, and hormone treatment. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 98, 2805–2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Piñeros MA, Tian J, Yao Z, Sun L, Liu J, Shaff J, Coluccio A, Kochian LV, Liao H. 2013. Low pH, aluminum, and phosphorus coordinately regulate malate exudation through GmALMT1 to improve soybean adaptation to acid soils. Plant Physiology 161, 1347–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Sun L, Yao Z, Liao H, Tian J. 2012. Comparative analysis of PvPAP gene family and their functions in response to phosphorus deficiency in common bean. PLoS ONE 7, e38106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Tian J, Lam HM, Lim BL, Yan X, Liao H. 2010. Biochemical and molecular characterization of PvPAP3, a novel purple acid phosphatase isolated from common bean enhancing extracellular ATP utilization. Plant Physiology 152, 854–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Wang J, Zhao J, Tian J, Liao H. 2014. Control of phosphate homeostasis through gene regulation in crops. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 21, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszkay A, Kenk B, Schopfer P. 2003. Evidence for the involvement of cell wall peroxidase in the generation of hydroxyl radicals mediating extension growth. Planta 217, 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liszkay A, van der Zalm E, Schopfer P. 2004. Production of reactive oxygen intermediates O2·–, H2O2, and ·OH by maize roots and their role in wall loosening and elongation growth. Plant Physiology 136, 3114–3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PD, Xue YB, Chen ZJ, Liu GD, Tian J. 2016. Characterization of purple acid phosphatases involved in extracellular dNTP utilization in Stylosanthes. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 4141–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Qiu W, Gao W, Tyerman SD, Shou H, Wang C. 2016. OsPAP10c, a novel secreted acid phosphatase in rice, plays an important role in the utilization of external organic phosphorus. Plant, Cell & Environment 39, 2247–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minic Z, Jamet E, Négroni L, Arsene der Garabedian P, Zivy M, Jouanin L. 2007. A sub-proteome of Arabidopsis thaliana mature stems trapped on Concanavalin A is enriched in cell wall glycoside hydrolases. Journal of Experimental Botany 58, 2503–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Riley JP. 1962. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Neuteboom LW, Ng JM, Kuyper M, Clijdesdale OR, Hooykaas PJ, van der Zaal BJ. 1999. Isolation and characterization of cDNA clones corresponding with mRNAs that accumulate during auxin-induced lateral root formation. Plant Molecular Biology 39, 273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olczak M, Ciuraszkiewicz J, Wójtowicz H, Maszczak D, Olczak T. 2009. Diphosphonucleotide phosphatase/phosphodiesterase (PPD1) from yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus L.) contains an iron-manganese center. FEBS Letters 583, 3280–3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olczak M, Kobiałka M, Watorek W. 2000. Characterization of diphosphonucleotide phosphatase/phosphodiesterase from yellow lupin (Lupinus luteus) seeds. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1478, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo M, Ward M, Bains S, Molina M, Blackstock W, Gil C, Nombela C. 2000. A proteomic approach for the study of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall biogenesis. Electrophoresis 21, 3396–3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxton WC, Lambers H. 2015. Phosphorus: back to the roots. In: Plaxton WC, Lambers H, eds. Annual Plant Reviews, Volume 48, Phosphorus metabolism in plants. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Zhao J, Tian J, Chen L, Sun Z, Guo Y, Lu X, Gu M, Xu G, Liao H. 2012. The high-affinity phosphate transporter GmPT5 regulates phosphate transport to nodules and nodulation in soybean. Plant Physiology 159, 1634–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghothama KG. 1999. Phosphate acquisition. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 50, 665–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WD, Park J, Tran HT, Del Vecchio HA, Ying S, Zins JL, Patel K, McKnight TD, Plaxton WC. 2012. The secreted purple acid phosphatase isozymes AtPAP12 and AtPAP26 play a pivotal role in extracellular phosphate-scavenging by Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 6531–6542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez AA, Grunberg KA, Taleisnik EL. 2002. Reactive oxygen species in the elongation zone of maize leaves are necessary for leaf extension. Plant Physiology 129, 1627–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares NC, Francisco R, Ricardo CP, Jackson PA. 2007. Proteomics of ionically bound and soluble extracellular proteins in Medicago truncatula leaves. Proteomics 7, 2070–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C, Bauer S, Brininstool G, et al. . 2004. Toward a systems approach to understanding plant cell walls. Science 306, 2206–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Suen PK, Zhang Y, Liang C, Carrie C, Whelan J, Ward JL, Hawkins ND, Jiang L, Lim BL. 2012. A dual-targeted purple acid phosphatase in Arabidopsis thaliana moderates carbon metabolism and its overexpression leads to faster plant growth and higher seed yield. New Phytologist 194, 206–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Tian J, Zhang H, Liao H. 2016a. Phytohormone regulation of root growth triggered by P deficiency or Al toxicity. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 3655–3664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun LM, Zhang JZ, Hu CG. 2016b. Characterization and expression analysis of PtAGL24, a SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE/AGAMOUS-LIKE 24 (SVP/AGL24)-type MADS-box gene from trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.). Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Onouchi H, Kondo M, Hara-Nishimura I, Nishimura M, Machida C, Machida Y. 2001. A subtilisin-like serine protease is required for epidermal surface formation in Arabidopsis embryos and juvenile plants. Development 128, 4681–4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Liao H. 2015. The role of intracellular and secreted purple acid phosphatases in plant phosphorus scavenging and recycling. In: Plaxton WC, Lambers H, eds. Annual Plant Reviews, Volume 48, Phosphorus metabolism in plants. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Liao H, Wang XR, Yan XL. 2003. Phosphorus starvation-induced expression of leaf acid phosphatase isoforms in soybean. Acta Botanica Sinica 45, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Wang C, Zhang Q, He X, Whelan J, Shou H. 2012. Overexpression of OsPAP10a, a root-associated acid phosphatase, increased extracellular organic phosphorus utilization in rice. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 54, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torki M, Mandaron P, Thomas F, Quigley F, Mache R, Falconet D. 1999. Differential expression of a polygalacturonase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecular & General Genetics 261, 948–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran HT, Hurley BA, Plaxton WC. 2010a. Feeding hungry plants: the role of purple acid phosphatases in phosphate nutrition. Plant Science 179, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tran HT, Qian W, Hurley BA, She YM, Wang D, Plaxton WC. 2010b. Biochemical and molecular characterization of AtPAP12 and AtPAP26: the predominant purple acid phosphatase isozymes secreted by phosphate-starved Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell & Environment 33, 1789–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyburski J, Dunajska K, Tretyn A. 2009. Reactive oxygen species localization in roots of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings under phosphate deficiency. Plant Growth Regulation 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vance CP, Uhde-Stone C, Allan DL. 2003. Phosphorus acquisition and use: critical adaptations by plants for securing a nonrenewable resource. New Phytologist 157, 423–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Uexküll HR, Mutert E. 1995. Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant and Soil 171, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Si Z, Li F, Xiong X, Lei L, Xie F, Chen D, Li Y, Li Y. 2015. A purple acid phosphatase plays a role in nodule formation and nitrogen fixation in Astragalus sinicus. Plant Molecular Biology 88, 515–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Li Z, Qian W, et al. . 2011. The Arabidopsis purple acid phosphatase AtPAP10 is predominantly associated with the root surface and plays an important role in plant tolerance to phosphate limitation. Plant Physiology 157, 1283–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lu S, Zhang Y, Li Z, Du X, Liu D. 2014. Comparative genetic analysis of Arabidopsis purple acid phosphatases AtPAP10, AtPAP12, and AtPAP26 provides new insights into their roles in plant adaptation to phosphate deprivation. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 56, 299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SB, Hu Q, Sommerfeld M, Chen F. 2004. Cell wall proteomics of the green alga Haematococcus pluvialis (Chlorophyceae). Proteomics 4, 692–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yan X, Liao H. 2010. Genetic improvement for phosphorus efficiency in soybean: a radical approach. Annals of Botany 106, 215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson BS, Lei Z, Dixon RA, Sumner LW. 2004. Proteomics of Medicago sativa cell walls. Phytochemistry 65, 1709–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Shou H, Xu G, Lian X. 2013. Improvement of phosphorus efficiency in rice on the basis of understanding phosphate signaling and homeostasis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 16, 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Lin Y, Liu P, Chen Q, Tian J, Liang C. 2017. Data from: Association of extracellular dNTP utilization with a GmPAP1-like protein identified in cell wall proteomic analysis of soybean roots. Dryad Digital Repository. https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6t1f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Somerville C, Anderson CT. 2014. POLYGALACTURONASE INVOLVED IN EXPANSION1 functions in cell elongation and flower development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26, 1018–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Liang C, Zhang Q, Chen Z, Xiao B, Tian J, Liao H. 2014. SPX1 is an important component in the phosphorus signalling network of common bean regulating root growth and phosphorus homeostasis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3299–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Su S, Xu Y, Zhao Y, Yan A, Huang L, Ali I, Gan Y. 2014. The effects of fluctuations in the nutrient supply on the expression of five members of the AGL17 clade of MADS-box genes in rice. PLoS ONE 9, e105597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Forde BG. 1998. An Arabidopsis MADS box gene that controls nutrient-induced changes in root architecture. Science 279, 407–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yu L, Yung KF, Leung DY, Sun F, Lim BL. 2012. Over-expression of AtPAP2 in Camelina sativa leads to faster plant growth and higher seed yield. Biotechnology for Biofuels 5, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Johnson BJ, Kositsup B, Beers EP. 2000. Exploiting secondary growth in Arabidopsis. Construction of xylem and bark cDNA libraries and cloning of three xylem endopeptidases. Plant Physiology 123, 1185–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Fu J, Liao H, He Y, Nian H, Hu Y, Qiu L, Dong Y, Yan X. 2004. Characterization of root architecture in an applied core collection for phosphorus efficiency of soybean germplasm. Chinese Science Bulletin 49, 1611–1620. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CQ, Zhu XF, Hu AY, Wang C, Wang B, Dong XY, Shen RF. 2016. Differential effects of nitrogen forms on cell wall phosphorus remobilization are mediated by nitric oxide, pectin content, and phosphate transporter expression. Plant Physiology 171, 1407–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Alvarez S, Marsh EL, et al. . 2007. Cell wall proteome in the maize primary root elongation zone. II. Region-specific changes in water soluble and lightly ionically bound proteins under water deficit. Plant Physiology 145, 1533–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Chen S, Alvarez S, Asirvatham VS, Schachtman DP, Wu Y, Sharp RE. 2006. Cell wall proteome in the maize primary root elongation zone. I. Extraction and identification of water-soluble and lightly ionically bound proteins. Plant Physiology 140, 311–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XF, Shi YZ, Lei GJ, et al. . 2012. XTH31, encoding an in vitro XEH/XET-active enzyme, regulates aluminum sensitivity by modulating in vivo XET action, cell wall xyloglucan content, and aluminum binding capacity in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 24, 4731–4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]