Protection against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Brassica napus is mediated via dynamic transcription factor networks and cellular redox homeostasis directly at the site of infection.

Keywords: Brassica napus, disease, oilseed rape, plant-pathogen interactions, RNA seq, redox, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, transcription factor network

Abstract

Brassica napus is one of the world’s most valuable oilseeds and is under constant pressure by the necrotrophic fungal pathogen, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, the causal agent of white stem rot. Despite our growing understanding of host pathogen interactions at the molecular level, we have yet to fully understand the biological processes and underlying gene regulatory networks responsible for determining disease outcomes. Using global RNA sequencing, we profiled gene activity at the first point of infection on the leaf surface 24 hours after pathogen exposure in susceptible (B. napus cv. Westar) and tolerant (B. napus cv. Zhongyou 821) plants. We identified a family of ethylene response factors that may contribute to host tolerance to S. sclerotiorum by activating genes associated with fungal recognition, subcellular organization, and redox homeostasis. Physiological investigation of redox homeostasis was further studied by quantifying cellular levels of the glutathione and ascorbate redox pathway and the cycling enzymes associated with host tolerance to S. sclerotiorum. Functional characterization of an Arabidopsis redox mutant challenged with the fungus provides compelling evidence into the role of the ascorbate-glutathione redox hub in the maintenance and enhancement of plant tolerance against fungal pathogens.

Introduction

Brassica napus (oilseed rape) is the second most valuable oilseed crop in the world and is vulnerable to white stem rot caused by the necrotrophic ascomycete Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, one of the most devastating fungal crop pathogens (Bolton, 2006; Hegedus and Rimmer, 2005). Currently, control of S. sclerotiorum relies heavily on the application of broad-spectrum fungicides (Bradley et al., 2006) as few resistant cultivars have been developed and microbial biocontrol methods, although promising, have yet to be implemented (Fernando et al., 2007; Khot et al., 2011). Developing new strategies to combat yield losses in B. napus requires a thorough understanding of the genes and gene regulatory networks underlying the plant defense response, especially in existing tolerant breeding cultivars (Garg et al., 2010a).

B. napus is vulnerable to carpogenic attack from S. sclerotiorum; however, for the fungus to penetrate the host plant, ascospores require an external energy source (Garg et al., 2010b; Hegedus and Rimmer, 2005; Mclean, 1958). Field-based evidence has shown that fungal colonization of petals may provide a nutrient source for producing the infection cushions required for penetrating mature leaves (Jamaux et al., 1995; Huang et al. 2008). Unfortunately, all recent work directed at understanding the pathosystem uses either an artificial sugar-phosphate based ascospore assay (Garg et al., 2013) or a myceliogenic infection using sclerotia germinated on fungal growth media (Wu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2009). As defense activation likely occurs at the petal inoculum-leaf interface, there is a need to understand global transcriptional responses directly at the infection site under conditions reflective of natural Sclerotinia disease transmission.

Plants have dynamic signalling networks to carefully balance growth and defense processes and maximize fitness (Huot et al., 2014). Pathogen perception in the host is orchestrated in part through pathogen associated molecular pattern (PAMP) detection via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Following PRR activation, subsequent signal transduction to the nucleus transcriptionally reprograms the cell (Park and Ronald, 2012; Zipfel, 2014). PAMP detection elicits a signalling cascade through Ca2+ channel activation, nitric oxide signalling, reactive oxide species (ROS) bursts, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades (Boller and Felix, 2009; Meng and Zhang, 2013). Effective signal transduction leads to activation of transcription factors (TFs) that regulated bioprocesses responsible for plant defense (Schluttenhofer and Yuan, 2015; Tsuda and Somssich, 2015). Defense to necrotrophic fungi is partially controlled via jasmonic acid (JA)/ethylene (ET) hormone signalling (Denancé et al., 2013). These hormones activate defense genes and stimulate production of antimicrobial compounds including glucosinolates and their derivatives (Wu et al., 2014). Restriction of pathogen growth via PAMP signalling is referred to as PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI), and is generally synonymous with basal plant defense.

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum produces a suite of digestive enzymes to degrade its host, however its main pathogenicity factor is oxalic acid (OA, Cessna et al., 2000). OA has a dual role of initially suppressing host cell ROS signalling, then subsequently eliciting ROS and plant cell death (Horbach et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011). The ascorbate-glutathione (ASC-GSH) pathway is at the core of the plant antioxidant system, which protects ROS signalling and reduces H2O2 toxicity (Foyer and Noctor, 2011; de Pinto et al., 2012). Previous microarray-based experiments have implicated the antioxidant response in B. napus defense against S. sclerotiorum (Yang et al., 2007); however, the physiological changes contributing to antioxidant-mediated defenses and the transcriptional regulation of these processes has yet to be studied.

Recent work profiling infected B. napus stem tissue has provided insight into the molecular processes that underlie defense to S. sclerotiorum (Wu et al., 2016). For example, genes involved in glucosinolate biosynthesis and chitinase activity were highly upregulated early in the defense response in resistant B. napus (Wu et al., 2016) and is consistent with findings in resistant B. napus leaves infected with the facultative necrotroph Leptosphaeria maculans (Becker et al. 2017a). In B. napus cv. Zhongyou821 (ZY821), a moderately tolerant cultivar, a putative resistance-associated quantitative trait locus has been identified as INDOLE GLUCOSINOLATE METHYL TRANSFERASE 5 (Li et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2013). Activation of glucosinolate biosynthesis is transcriptionally controlled through gene regulatory networks at the leaf surface (Schweizer et al., 2013; Sønderby et al., 2010). Thus, thorough analyses of the transcriptional circuitry operative directly at the host pathogen interface at the leaf surface should identify regulatory elements that control disease progression.

In this study, we present a structural, molecular, and physiological investigation of the B. napus defense response to S. sclerotiorum in susceptible and tolerant hosts. The use of a petal inoculation method with S. sclerotiorum ascospores mimics disease transmission under real-world conditions. Global transcriptome profiling coupled with a comprehensive bioinformatic analysis revealed distinct biological processes not previously described in this system directly at the site of infection. Further, we used the latest information of B. napus TFs and promoter motifs to develop predictive gene regulatory networks responsible for disease tolerance in ZY821. This includes a putative ethylene response factor-controlled transcriptional circuit regulating redox state homeostasis genes that slows disease progression directly at and adjacent to the first site of infection in the leaf.

Materials and methods

Brassica napus growth conditions

The two B. napus cultivars used for all experiments are the susceptible B. napus L. cv. Westar (Westar) and B. napus L. cv. Zhongyou821 (ZY821). Westar seeds stored at 4°C were planted in Sunshine Mix No.1 soil and grown at 22°C with 50–70% humidity in a growth chamber with long day conditions (16 hours light, 8 hours dark 150–200 µE/m2/s). ZY821 plants were treated similarly, however 1 month after planting they were subjected to a four-week vernalization treatment (8 hours light, 16 hours dark, 40% humidity, 8–10°C and 100 µE/m2/s), before being transferred back to long day conditions. Both cultivars were inoculated at 30–50% bloom stage.

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum inoculum preparation

Sclerotinia sclerotiorum field-collected ascospores were provided by Dr. K. Rashid, (Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, Morden, Manitoba), and stored at 4°C in desiccant in the dark. Inoculum was made by suspending ascospores at a concentration of 8 x104 spores per mL in a 0.02% Tween80 (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/) solution. Following, 30µL of the solution was pipetted onto senescing petals placed in a sterile empty petri plate and sealed with parafilm. The Tween80 solution without ascospores was applied to petals and used for a mock inoculation control. Petals were incubated for 72 hours prior to being used in the leaf inoculation experiments to allow ascospore germination.

Leaf inoculation and tissue collection

At approximately 1PM, either mock-inoculated petals or infected petals and S. Sclerotiorum hyphae were placed onto healthy leaves and incubated in clear plastic bags to increase humidity and promote S. sclerotiorum infection. Lesion size was measured at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120hpi (hours post inoculation). For RNA collection and redox assays, lesions and surrounding 1cm of healthy leaf tissue were excised and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. For each biological replicate, lesions were pooled from a minimum of 3 different plants and ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen.

Light microscopy

Leaf tissues directly at the infection site were fixed in a solution of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1.6% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS. Tissue processing, mounting, and imaging was carried out exactly as described in Chan and Belmonte (2013).

Scanning electron microscopy

Fresh leaf tissues were mounted on aluminum stubs using double stick carbon tape. Images were taken of fresh leaves on a Hitachi TM-1000 Tabletop microscope and collected using the TM-1000 software.

RNA Isolation and cDNA sequencing library synthesis

RNA was isolated using Invitrogen Plant RNA Purification Reagent, and subsequently treated with the Ambion Turbo DNA-free DNase kit per the manufacturer’s protocol (https://www.thermofisher.com). Quantity and purity were assessed spectrophotometrically and quality of RNA samples was verified using RNA Nano Chips on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (http://www.genomics.agilent.com/). Following, mRNA was isolated from the total RNA pool using the NEB Next® Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs, https://www.neb.ca/) per manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications: all reaction volumes were halved and only 7.5µL of Oligo d(T)25 beads were used per sample. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared from isolated mRNA using the alternate HTR protocol (C2) described in Kumar et al. (2012) beginning at first strand cDNA synthesis with the following modifications: NEXTflex™ ChIP-Seq Barcodes (Bioo Scientific, http://www.biooscientific.com/) were used as adaptors for the adapter ligations and NEXTflex™ PCR Primer Mix was used for the library PCR enrichment. Library size was verified using a High Sensitivity DNA chip on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Libraries were pooled and size selected using an E-Gel® SizeSelect™ 2% agarose gel (Life Technologies, www.thermofisher.com) isolating 250–500 base pair fragments. Fragments were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform at the Génome Québec Innovation Centre (Montreal, Canada, http://gqinnovationcenter.com/). Sequencing was performed in high output mode, producing 100bp single end reads.

Bioinformatics pipeline

Raw Fastq files were cleaned using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014), clipping adapter sequences, performing a 6 base head crop, clipping reads when the average base quality score fell below 30 in 4 base sliding window, and dropping remaining reads shorter than 50nt. The splice junction mapping software TopHat (v2.0.13, Trapnell et al., 2012, http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) was used to align and map the trimmed reads to B. napus genome v5.0 (Chalhoub et al., 2014, http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/brassicanapus/) and the S. sclerotiorum genome (Amselem et al., 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_AAGT00000000.1). Transcripts from each sample were assembled with Cufflinks (v2.2.1, https://github.com/cole-trapnell-lab/cufflinks) using the transcript annotation files to guide assembly. Individual samples’ transcript assemblies were merged with the reference. For a conservative and robust prediction of novel transcripts, the merged assembly was used to predict open reading frames with Transdecoder (v2.0.1, https://transdecoder.github.io/), and predicted genes were only kept if they were located within intergenic regions and the largest translated ORF had a blast hit using BLASTp (v2.2.30, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to Arabidopsis TAIR10 (http://arabidopsis.org), with an E-value cut off<1 × 10-10. Quantification of mapped reads was done with the Tuxedo package (v2.2.1, http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks). This included differential expression analysis, and normalization of transcript abundances across samples in FPKM. Fuzzy k-means clustering analysis was performed per Belmonte et al. (2013). Following, selected gene sets were used as input into SeqEnrich (Becker et al., 2017b), a program adapted for B. napus from ChipEnrich (Belmonte et al., 2013). SeqEnrich contains the most current information on B. napus TFs, promoter motifs, and gene ontology (GO) available, and uses these data to produce predictive regulatory networks. Networks produced with SeqEnrich were visualized in Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

One microgram of total RNA from each biological replicate was used to construct cDNA libraries for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using the Maxima First Strand Synthesis Kit (https://www.thermofisher.com/). qPCR was carried out using SsoFast Evagreen Supermix (http://www.bio-rad.com/), following manufacturer’s instructions, but proportionally adjusting to a 10µL reaction volume. Reaction steps were performed as follows: 95°C for 30 seconds, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 2 seconds and 60°C for 5 seconds. The ΔΔCt method, using the ubiquitin family protein BnaC08g11930D as a housekeeping gene in B. napus, was used to calculate fold changes between mock and S. sclerotiorum inoculated treatments in both cultivars. For Arabidopsis experiments, EF1ALFA (AT5G60390) was used as a housekeeping gene (Nicot et al., 2005). Statistical significance was calculated using the Students t-test (P<0.05) and all primer sequences used are presented in Table S9.

Enzyme assays

S. sclerotiorum inoculation and tissue collection was carried out as described above. Quantification of reduced and oxidized forms of ascorbate and glutathione were carried out per Zhang and Kirkham (1996). Enzymatic activity of ascorbate peroxidase (APX), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDAR), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), and glutathione reductase (GR) were carried out exactly as described in Belmonte and Stasolla (2009).

Arabidopsis pathogenicity experiments

Arabidopsis thaliana and T-DNA insertion lines were obtained from The Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (Ohio State University, https://abrc.osu.edu/). Seeds were surface sterilized using 75% ethanol and grown on Murashige and Skrooge medium (Phytotechnology Labratories) with 1% phytagel at pH 5.7. Seeds were vernalized for 3 days at 4 °C before being transferred to an incubation chamber for two weeks. Seedlings were then transplanted into Sunshine Mix #1 soil and kept at 22 °C a 16-h photoperiod. For vitamin c defective 2 (SALK_146824) Arabidopsis plants, T-DNA insertion was verified with PCR. One rosette leaf of four-week old Arabidopsis plants was inoculated with a 4.5mm diameter agar plug containing growing S. sclerotiorum hyphae under high humidity levels maintained with a large clear plastic bag. Progression of infection at 24 and 48hpi was determined by measuring the leaf length and width and calculating elliptical area of infection in at least 14 plants per treatment. Progression of infection at 72hpi was determined by dividing total number of infected rosette leaves by total number of inoculated rosette leaves. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR reactions were carried out as described above. Quantification of ascorbic acid (ASC) levels was performed as per Gillespie and Ainsworth (2007).

Accession numbers

Raw and processed sequence data are available from the National Center for Biotechnology’s (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus as GEO Series GSE81545.

Results

Petal inoculation is essential for S. sclerotiorum infection

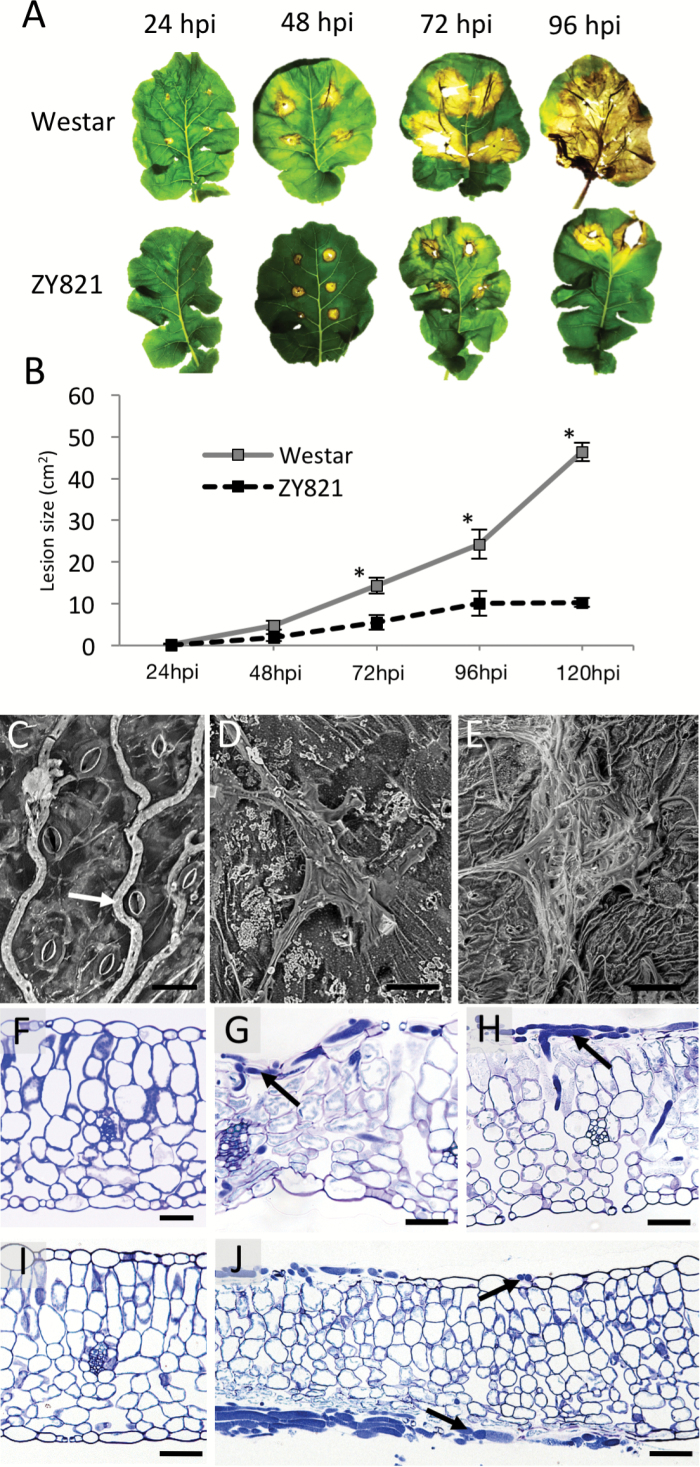

We developed a S. sclerotiorum petal inoculation method to identify how B. napus responds to fungal attack at the earliest stage of the infection process. Disease progression was assayed in universally susceptible (cv. Westar) and tolerant (cv. ZY821) genotypes of B. napus. The petal inoculation method replicates the infection process that naturally occurs in the field (Jamaux et al., 1995; Huang et al. 2008). When leaves were infected with a senescing petal, we observed 100% infection compared to 20% with a fresh petal. Profound differences in disease progression were observed at 48hpi, with little green tissue remaining by 96hpi in the susceptible host (Fig. 1A). We measured lesion area and observed statistically larger lesions in susceptible hosts at 72, 96, and 120hpi, with a 78% increase by 120hpi (Fig. 1B). Scanning electron microscopy revealed topographic features of the infection process directly at the infection site. S. sclerotiorum hyphae did not appear to penetrate host tissues via stomata (Fig. 1C). Infection cushions were observed in both cultivars (Fig. 1D and 1E); however, they were qualitatively larger and more abundant on the ZY821 leaf surface.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of the Brassica napus-Sclerotinia sclerotiorum pathosystem. (A) S. sclerotiorum lesion progression in B. napus susceptible (cv. Westar) and tolerant (cv. ZY821) genotypes. (B) Lesion size measurements±standard deviation from 24–120 hours post-inoculation (hpi) in Westar and ZY821, * indicates ANOVA P-value<0.05. (C) Scanning electron micrograph of S. sclerotiorum hyphae (arrow) avoiding stomata on the adaxial epidermis of Westar 24hpi. Representative S. sclerotiorum infection cushions on abaxial epidermis of (D) Westar and (E) ZY821. (F-J) Light microscopy of transverse leaf sections stained with Toluidine Blue O. (F) Un-inoculated section of healthy Westar tissue. (G) Westar leaf 48hpi showing extensive membrane shrinkage caused by S. sclerotiorum, and darkly staining hyphae (arrow). (H) Infection cushion (arrow) on adaxial epidermis of Westar 48hpi. (I) Un-inoculated healthy section of ZY821 tissues. (J) Cross-section of infected ZY821 leaves showing limited cellular degradation in advance of S. sclerotiorum hyphae (arrows). Scale bars, C: 80µm; D: 60µm; E: 120µm; F-J: 50µm.

We then used light microscopy directly at the infection site in the susceptible (Fig. 1F-H) and tolerant (Fig. 1I-J) hosts. Data revealed S. sclerotiorum growth inside susceptible epidermal cells at 48hpi and membrane shrinkage in advance of the infecting hyphae (Fig. 1G). Cellular degradation indicated by membrane shrinkage was only observed in the cells surrounding the hyphae in the tolerant cultivar. Similarly, fungal hyphae could penetrate the mesophyll in susceptible leaf tissues (Fig. 1H) more readily than in tolerant hosts (Fig. 1J).

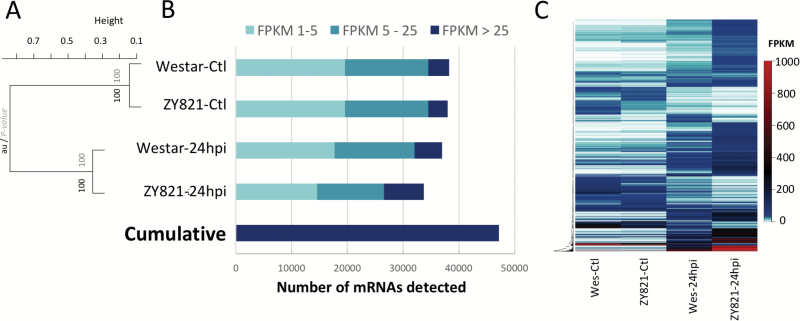

Global patterns of gene activity in response to S. sclerotiorum

To interrogate global changes in gene activity and elucidate potential regulatory elements contributing to the tolerant phenotype observed in ZY821, we performed high-throughput RNA-seq on both genotypes at 24hpi using ascospore- and mock-inoculated petals (Fig. 2). Reads were mapped to the reference assembly of B. napus v5.0 (Chalhoub et al., 2014) and S. sclerotiorum (Amselem et al., 2011). Total numbers of reads per biological replicate for each species are presented in Tables S1 and S2 respectively. For plant transcripts, we considered a transcript ‘detected’ if the Fragments Per Kilobase of gene per Million reads mapped (FPKM) level was≥1 (Bhardwaj et al., 2015; Chan et al., 2016). Hierarchical clustering of detected transcripts grouped samples together based on treatment, indicating both cultivars underwent a broad shift in gene activity in response to S. sclerotiorum infection (Fig. 2A). Transcripts were further divided into those with low (1≤FPKM<5), moderate (5≤FPKM<25), or high (FPKM≥25) accumulation levels. Mock-inoculated samples in both cultivars had a similar distribution of lowly, moderately, and highly accu mulating mRNAs (Fig. 2B). In these mock treatments, a total of 38,254 transcripts were detected in Westar and 37,977 in ZY821. In leaf tissues infected with S. sclerotiorum, we detected 36,986 mRNAs in the susceptible host and 9% fewer (33,720) in ZY821. In the tolerant host, a greater percentage of detected transcripts had an FPKM>25 (21.1%) as compared to susceptible Westar (13.4%). Inclusive of all treatment groups we detected 47,154 mRNAs, with the most abundant 10,000 mRNAs showing distinct accumulation patterns between the two cultivars and treatments (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

RNA Sequencing of susceptible (Westar) and tolerant (ZY821) genotypes of B. napus infected with S. sclerotiorum. (A) Hierarchical clustering of genes detected with a minimum FPKM of 1, with approximately unbiased (au) values in black and bootstrap P-values in grey. (B) Distribution of transcript abundances in FPKM normalized across the four treatments. (C) Clustered heatmap of top 10,000 most highly abundant mRNAs.

Identification of unannotated genes with roles in plant defense

To identify whether previously unannotated genes play a role in B. napus defense to S. sclerotiorum, reads of individual samples were assembled, merged, and compared with the existing B. napus transcriptome annotation (Table S1, Chalhoub et al., 2014; Trapnell et al., 2012). To strengthen predictive power, only detected transcripts outside of existing gene models with protein blast hits to A. thaliana were retained. Using these criteria, a total of 1,233 previously unannotated transcripts were identified (Table S3) and graphed as a heatmap (Fig.S1). The 20 most abundant novel transcripts are presented in Table S4, and include potential homologues of characterized Arabidopsis lipid transfer genes, sulfur assimilators (ATP SULFURYLASE 1), protein regulators (POLYUBIQUITIN 10), and signal transducers (MAP KINASE 4; MPK4).

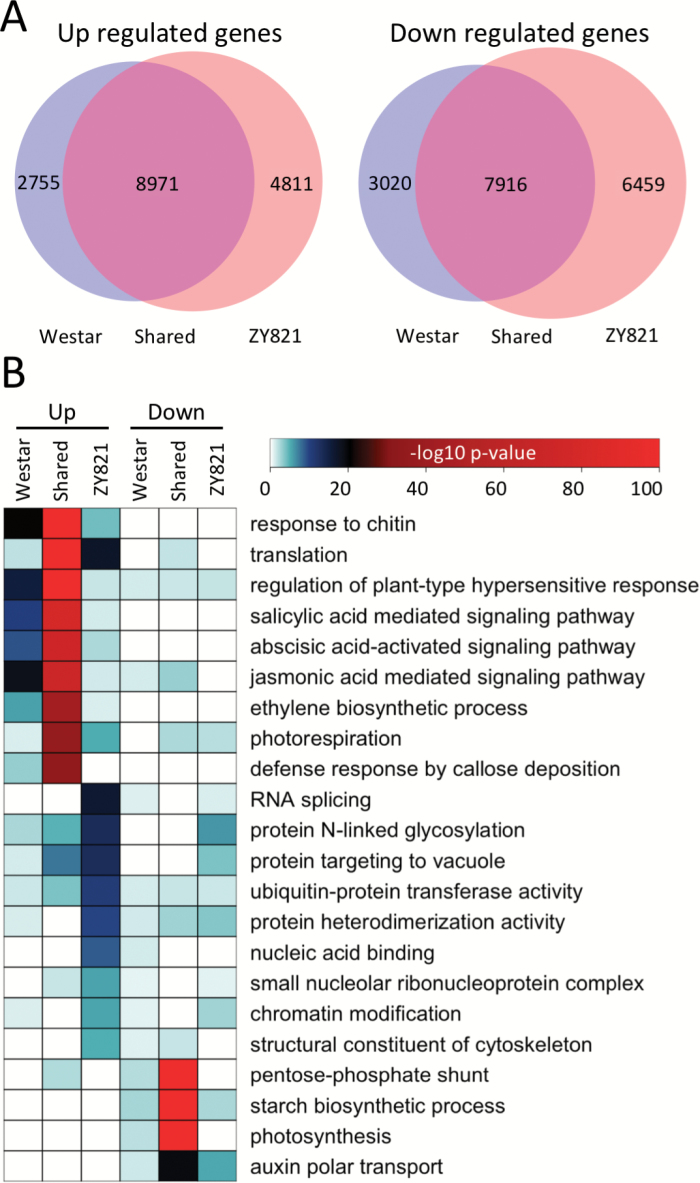

Differential gene activity in response to S. sclerotiorum infection

We then identified gene sets activated in B. napus in response to S. sclerotiorum in both susceptible and resistant cultivars. We found 53% of genes detected were differentially expressed (false discovery rate<0.05) in susceptible leaves with a total of 11,726 genes being differentially up- and 10,936 differentially downregulated. Overall, 65% of the genes were differentially expressed in the tolerant cultivar, with 13,782 up- and 14,375 downregulated. Although the majority of differentially expressed genes were shared between the two cultivars, we found relatively large number of genes specifically differentially expressed in each cultivar (Fig. 3A). This suggests large coordinated shifts in gene expression in susceptible and resistant hosts at early stages of the infection process.

Fig. 3.

Differential gene expression and gene ontology (GO) analysis. (A) Euler diagrams showing number of genes differentially expressed in susceptible (Westar) and tolerant (ZY821) genotypes of B. napus infected with S. sclerotiorum (false discovery rate<0.05). Overlapping segments represent genes differentially expressed in both genotypes. (B) Heatmap of a subset of significantly enriched GO terms. GO terms are considered statistically significant if the hypergeometric P-value<0.001. See also Table S5.

Gene ontology analysis reveals biological processes shared between tolerant and susceptible B. napus plants responding to S. sclerotiorum

To query the biological processes encoded within differentially expressed gene sets, we used the GO enrichment function of SeqEnrich (Becker et al., 2017b). GO terms were considered significantly enriched if the hypergeometric P-value<0.001 (Fig. 3B, Table S5). We predicted plant defense hormones to be active in both susceptible and tolerant leaves in response to S. sclerotiorum. Salicylic acid (P=2.72E-79), abscisic acid (P=1.85E-73), and jasmonic acid (P=2.73E-71) signalling processes, as well as response to ethylene (P=1.89E-69), were all enriched in genes upregulated in response to the fungus in both treatments (Table S5).

In response S. sclerotiorum, both susceptible and resistant hosts activated genes enriched for photorespiration (P=2.67E-36) and downregulated genes enriched for photosynthesis (P=5.06E-137) and starch biosynthetic processes (P=1.27E-180), suggesting inhibition of growth-related bioprocesses in response to pathogen. Likewise, in both genotypes shared downregulated genes were associated with auxin-activated signaling pathways (P=3.27E-06) and auxin polar transport (P=4.69E-06). Together, this is indicative of large-scale transcriptional reprogramming following infection with S. sclerotiorum in both genotypes that may modulate growth and metabolism.

Identification of biological processes activated specifically in B. napus tolerant to S. sclerotiorum

Next, we were interested in exploring the biological processes active in the 4,811 genes upregulated exclusively in tolerant hosts following pathogen exposure (Fig. 3B). We identified bioprocesses previously unassociated with B. napus defense against S. sclerotiorum, including RNA-splicing (P=3.49E-17) and chromatin modification (P=3.43E-06). Additionally, this gene set was associated with GO terms related to protein sorting and trafficking, including protein N-linked glycosylation (P=4.26E-14) and protein targeting to vacuole (P=5.52E-14), in which VACUOLAR SORTING RECEPTOR 1, vSNARE protein family members, and BZIP53 transcripts were also differentially up-regulated. Interestingly, the data also point to a role of the structural component of the cytoskeleton (P=8.60E-06), with both ACTIN 2 (ACT2) and TUBULIN BETA CHAIN 4 upregulated in ZY821 (Fig. S4, Table S6).

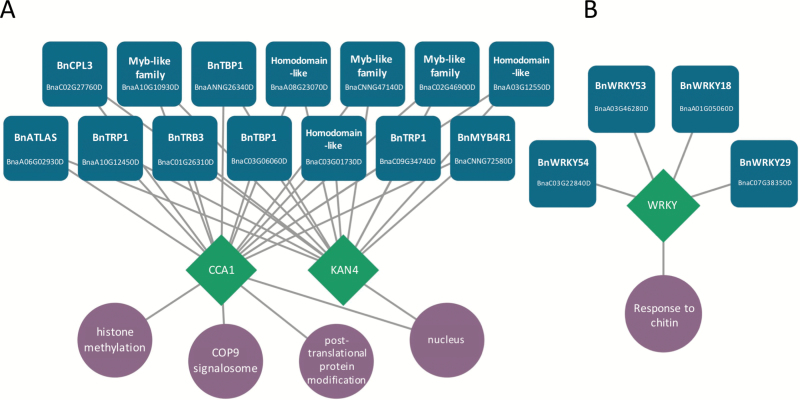

To identify potential regulatory networks controlling these biological processes, we used SeqEnrich (Becker et al., 2017b), which contains a curated database containing all current information on B. napus TFs, DNA sequence motifs, and GO terms. Using this program, TFs were associated with DNA sequence motifs overrepresented (P<0.001) in gene promoters within enriched GO terms. Two networks were identified in genes specifically upregulated in tolerant hosts at 24hpi (Table S7). C-terminal domain phosphatase-like 3 (BnaC02G27760D) and MYB TFs were predicted to bind to the CCA1 and KAN DNA promoter motifs upstream of genes enriched for histone methylation and protein modification (Fig. 4A). The same analysis also identified four WRKY DNA-binding proteins (WRKYs) predicted to contribute to the plant response to chitin (P=3.44E-05, Fig. 4B). The association of the CCA1 DNA motif with genes specifically upregulated in the tolerant cultivar led us to investigate whether circadian rhythm-regulated genes were globally affected at the RNA level in the two cultivars following exposure to S. sclerotiorum. We plotted the corresponding FPKMs of homologous genes shown to be circadian regulated in Arabidopsis (Covington et al., 2008), and show clear differences in how circadian clock associated gene sets respond to S. sclerotiorum in the two B. napus genotypes (Fig. S2). Both homologues of the master clock regulator CCA1 shared similar expression profiles in both genotypes, however LHY homologues accumulated at an average of 4.5 times higher in ZY821 control samples (Table S6).

Fig. 4.

Putative transcriptional regulation of Sclerotinia tolerance in B. napus. (A) Putative circuit controlled by CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED 1 (CCA1) and KAN4 binding sites. Transcription factors (blue squircles) are predicted to bind to the over-represented (P<0.001) DNA motifs (green diamonds) to control GO terms (purple circles). (B) Putative transcriptional circuit regulated by WRKY DNA binding motif.

Coexpression analysis reveals distinct patterns of gene activity and regulatory networks between susceptible and tolerant genotypes

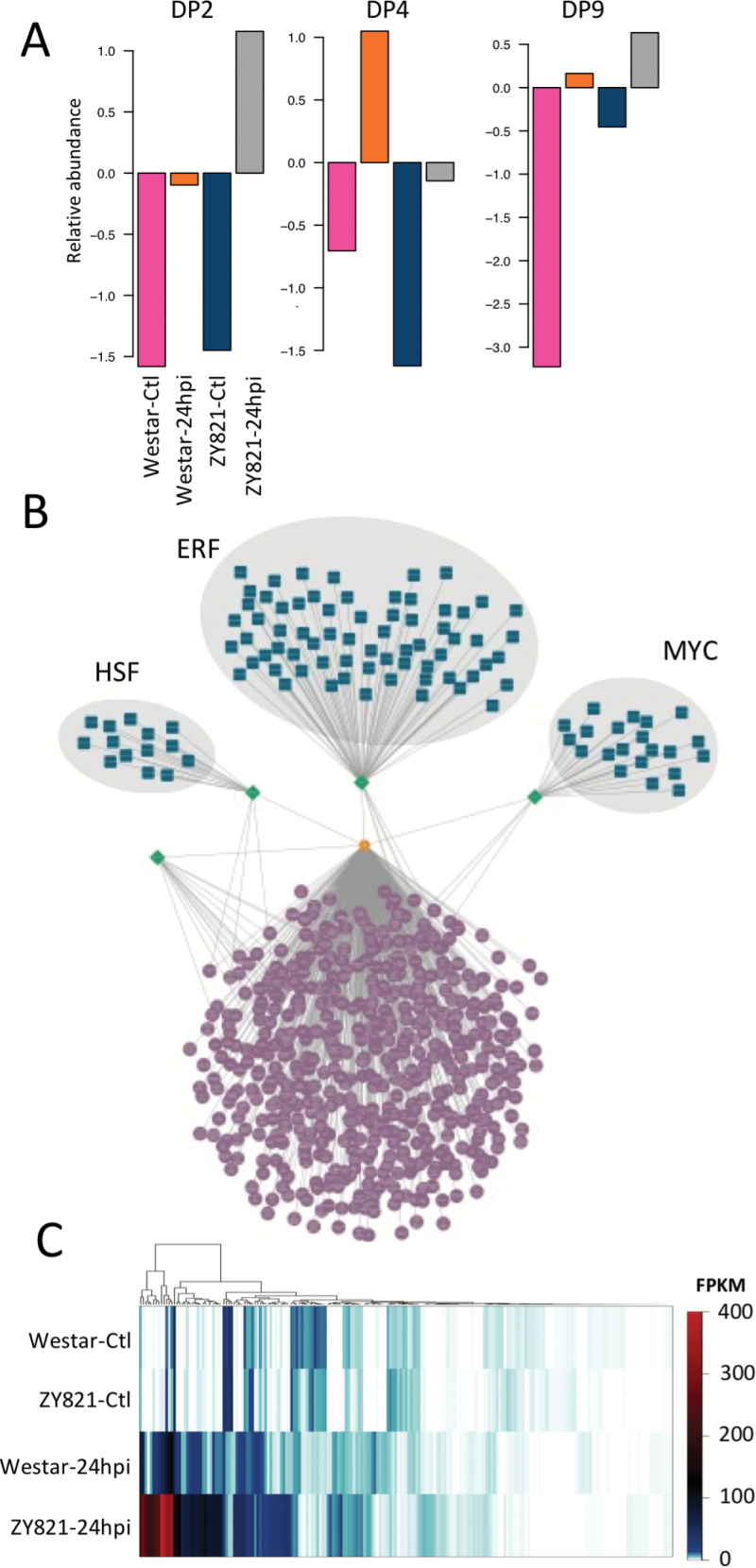

We used a modified fuzzy K-means clustering algorithm to identify coexpressed transcripts with finer patterns of gene activity than detectable with differential expression, and to group genes of similar expression profiles (Belmonte et al., 2013). Ten dominant patterns of gene activity (DPs) were determined, each containing anywhere from 599 to 9,536 genes with a median of 1,284 (Table S8). Our analysis identified patterns containing mRNAs abundant in infected Westar (DP4), infected ZY821 (DP2), or in both genotypes during infection (DP9; Fig. 5A). We also resolved patterns containing mRNAs that accumulated based on genotype. For example, mRNAs of DP8 accumulated primarily in Westar, and DP3 mRNAs primarily in ZY821 (Fig. S3).

Fig. 5.

Dominant patterns (DPs) of gene activity in susceptible (Westar) and tolerant (ZY821) genotypes of B. napus infected with S. sclerotiorum using fuzzy k-means clustering and enrichment analysis. (A) Bar plots representing relative abundance of mRNAs assigned to three DPs. (B) Predicted transcriptional module identified in DP2 (gold hexagon) accumulating primarily in the tolerant B. napus genotype at 24hpi. Sets of Heatshock Factors (HSF), Ethylene Response Factors (ERF) and MYC transcription factors (blue squircles) are predicted to bind to their overrepresented DNA motifs (P<0.001) up stream of genes enriched for gene ontology terms (purple circles). (C) Heatmap of all putative ERF coding transcripts.

Predicted TF-promoter interactions identified a putative transcriptional circuit in mRNAs accumulating in tolerant leaves at 24hpi (DP2). Heat-shock transcription factors (HSPs), ethylene responsive element binding factors (ERFs), and MYC-family TFs (MYCs) were predicted to control biological processes including defense signaling, protein biosynthesis and trafficking, secondary metabolite production, and redox regulation (Fig. 5B, Table S7). Further investigation of ERF-coding transcripts showed that the majority were upregulated in both genotypes following infection, but accumulated to much higher levels in the tolerant host (Fig. 5C).

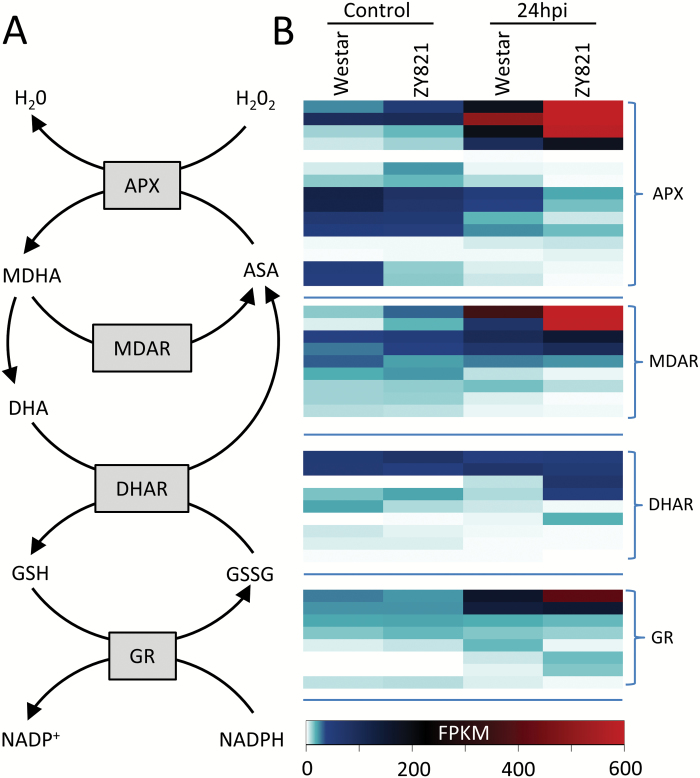

Activation of the cellular redox system in tolerant B. napus leaves

Identification of enriched redox-related GO terms in DP2 (Table S5) led us to investigate differences in the ascorbate-glutathione redox cycle between the two genotypes in response to pathogen attack (Fig. 6A). Transcripts encoding homologues of integral enzymes in the ascorbate-glutathione pathway including cytosolic ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE (APX) and GLUTATHIONE REDUCTASE (GR) accumulated up to 15- and 33-fold higher respectively, in infected leaves of tolerant ZY821 than in Westar (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Transcript analysis of ascorbate-glutathione redox cycling pathway in susceptible (Westar) and tolerant (ZY821) genotypes of B. napus infected with S. sclerotiorum. (A) Overview of the ascorbate-glutathione redox enzymes and products. (B) Accumulation of transcripts from all homologues of enzymes involved in pathway represented as heatmap.

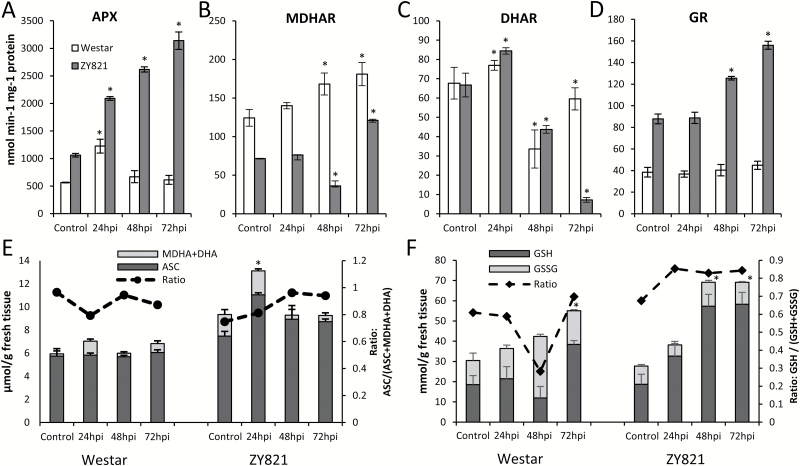

To study whether elevated transcript levels corresponded to real changes in ascorbate-glutathione redox balance we measured enzyme activities by quantifying small-molecule substrates (Fig. 7). APX activity was between 41–80% higher across each time point in ZY821 compared to Westar (Fig. 7A). Additionally, GR activity doubled in tolerant plants by 72hpi, whereas there was no significant increase in susceptible hosts (Fig. 7D). The total cellular ascorbate pool in ZY821 was higher than Westar for all time points, with only the ZY821 24hpi treatment showing a significant deviation from the endogenous levels in the control (Fig. 7E). Total glutathione levels and the glutathione redox ratio (GSH/(GSH+GSSG)) were similar in controls of both genotypes. In ZY821, the glutathione redox ratio remained relatively constant following infection and the total glutathione pool increased 60% at 48hpi. In Westar, the glutathione redox ratio decreased from 0.6 to 0.3 over the same period and the total glutathione pool increased by only 28% at 48hpi (Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Physiological measurements of ascorbate-glutathione redox cycling pathway in susceptible (Westar) and tolerant (ZY821) genotypes of B. napus infected with S. sclerotiorum. (A) Ascorbate peroxidase, (B) monodehydroascorbate reductase, (C) dehydroascorbate reductase, and (D) glutathione reductase enzymatic activity measured from infected leaves of B. napus. Levels and ratios of reduced and oxidized (E) ascorbate and (F) glutathione. Data represent mean of biological replicates±standard deviation, statistically significant change from control levels indicated by *. Abbreviations: APX, ascorbate peroxidase; ASC, reduced ascorbate; DHA, dehydroascorbate; DHAR, dehydroascorbate reductase; GR, glutathione reductase; GSH, reduced glutathione; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; MDHA, monodehydroascorbate; MDHAR, monodehydroascorbate reductase; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidized form; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced form.

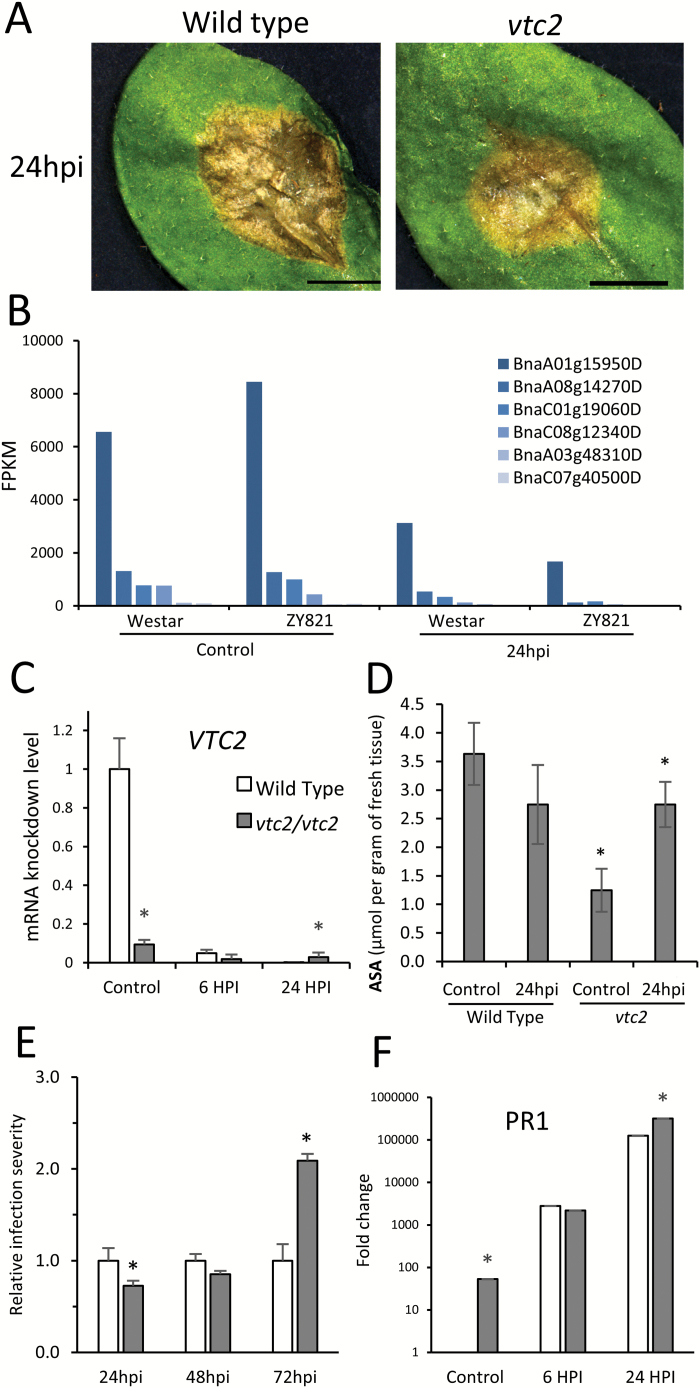

Redox homeostasis mutants in Arabidopsis are hyper-susceptible to Sclerotinia

To further validate the role of redox homeostasis in the plant defense response to S. sclerotiorum, we studied an Arabidopsis knockdown line of the rate-limiting enzyme of ascorbate biosynthesis, vitamin c defective 2 (vtc2, Fig. 8A). Loss-of-function mutants produce 10–25% of wild-type ascorbate levels (ASC, Pavet et al., 2005), limiting their capacity to buffer redox stress through the ascorbate-glutathione cycle. In B. napus, all VTC2 homologues are downregulated in response to infection at 24hpi (Fig. 8B), which corresponds to our observations in Arabidopsis as measured by qPCR (Fig. 8C). We assayed ASC levels at 24hpi in wild-type and vtc2 Arabidopsis plants. Although we found a 70% reduction of ASC in mock-inoculated vtc2, we observed a rescue to wild-type levels during infection (Fig. 8D). Phenotypically, infected vtc2 plants initially showed a delayed lesion spread; however, at 72hpi, the infection is twice as severe (Fig. 8E). We assessed activation of the plant defense response via qPCR detection of marker PATHOGENESIS-RELATED 1 (PR1; Fig. 8F) and found higher baseline levels in vtc2 plants, with increased abundances in both lines following contact with the pathogen.

Fig. 8.

Redox control of Sclerotinia infection in Arabiodpsis (A) Wild-type Col and vtc2 mutants infected with Sclerotinia 24hpi(B) FPKM levels of all detected homologues of VTC2 in S. sclerotiorum infected leaves of B. napus. (C) Relative mRNA levels of VTC2 at 6 and 24hpi in infected leaves measured by qPCR. (D) Ascorbate levels in wild-type and vtc2 Arabidopsis. (E) Lesion progression measured 72hpi compared to WT control (F) qPCR relative mRNA levels of infected plants for PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE 1 (PR1). Data represent mean of biological replicates±standard error, statistical significance was determined using a Students t-test with a minimum P<0.05 for statistical significance.

Discussion

Our analysis of the B. napus-S. sclerotiorum interaction directly at the host pathogen interface provides novel insight into the structural, molecular, and physiological changes in the B. napus leaf at the earliest stages of the infection process. We identified putative transcription factor circuits controlling biological processes and defense genes within the host plant in response to S. sclerotiorum controlling lesion spread and disease progression. A comprehensive investigation of redox homeostasis following S. sclerotiorum infection revealed pronounced genotypic differences between our two experimental host plants, providing physiological evidence for the tolerant phenotype of ZY821.

Previous studies investigating this pathosystem towards the later stages of the infection process in stem tissues used artificial nutrient sources to promote infection and is not reflective of disease transmission in the field (Wu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2009). Our method of using senescing petals simulates field conditions, as senescing petals likely provide the nutrients required for Sclerotinia to finance the production of toxins, cell wall degrading enzymes, and appressoria required to penetrate host tissues (Bolton, 2006). Interestingly, we did not observe stomatal penetration of leaves in either genotype, even though stomata are directly regulated via OA (Stotz and Guimaraes, 2004) and serve as ideal entry points for other pathogenic fungi (Kim et al., 2011). Instead, SEM and light microscopy data revealed advancing hyphae penetrating the physical barriers of the plant via infection cushions, the occurrence of which is correlated to Sclerotinia pathogenicity (Jurick and Rollins, 2007). An abundance of complex appressoria on the epidermis of ZY821 suggests S. sclerotiorum requires additional resources for colonization of the tolerant host. The cellular differences observed between the susceptible and tolerant cultivars provide additional structural evidence for the colonization strategy of S. sclerotiorum on the leaf surface.

Global RNA profiling of the B. napus infection site within the first 24 hours of the host pathogen interaction revealed large and coordinated shifts in gene activity. While large numbers of differentially expressed genes have been reported in stem tissues of Sclerotinia-resistant plants (Wu et al., 2016), we show a transcriptional response in ZY821 within hours of infection that may limit S. sclerotiorum penetration and colonization with the leaf. We discovered many differences in the amplitudes and attenuations of genes fundamental to the defense process, providing a new understanding of the molecular foundations of tolerance to Sclerotinia. For example, activation of both SA and JA/ethylene signal transduction networks in leaves 24 hpi supports a conserved defense response in both stem and leaf tissues following Sclerotinia infection (Wu et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2009). Interestingly, transcripts for SA biosynthesis, including ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE 1 (ICS1) homologues accumulated up to six times more in the susceptible line than in ZY821. This contradicts previous work of Zhao et al. (2009) who found ICS1 homologues downregulated in stem tissues of the same two genotypes 24hpi using a B. napus microarray. Although these differences may be explained by differential activation of homologues not included in the array used by Zhao et al. (2009), however, Wu et al. (2016) also found downregulation of ICS1 levels in both susceptible and resistant stem tissues. Thus, our work suggests organ-specific transcriptional regulation of hormone biosynthesis in response to S. sclerotiorum.

Further, mRNAs associated with ethylene biosynthesis and signaling were more abundant in tolerant leaves. Levels of OCTADECANOID-RESPONSIVE ARABIDOPSIS 59 (ORA59), a key transcriptional activator of ethylene and JA signaling (Caarls et al., 2015), were 6.5-fold higher in tolerant hosts. Given that SA directly represses ORA59 transcription (Caarls et al., 2015), accumulation of SA through ICS1 in susceptible host leaves may be responsible for limiting JA/ethylene associated defence activation in foliar tissues. This suggests that upstream restriction of SA biosynthesis may prevent SA-mediated JA antagonism (Van der Does et al., 2013) in tolerant B. napus leaves and highlights the importance of studying the plant response at the first point of contact with S. sclerotiorum.

MAPK signalling cascades are essential to defense and transduce JA signals to transcriptional reprogramming (Meng and Zhang, 2013; Takahashi et al., 2007). Our study identified differentially expressed MAPK genes between both genotypes, suggesting differences in how cells interpret and respond to biotic stressors. In Arabidopsis, MPK4 is a important regulator of PTI and activator of WRKY33 (Qiu et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012). We identified an unannotated MPK4 homologue (CUFF.20400.1) detected exclusively and abundantly in infected ZY821 through our transcriptional analysis, and validated using qPCR. Thus, CUFF.20400.1-mediated signaling may contribute to S. sclerotiorum tolerance in ZY821 additionally. This also illustrates how RNA sequencing is an effective tool to identify critical genetic differences in cultivar-specific defense transcripts beyond existing genome assemblies.

Suppression of fungal attack relies on timely activation of TFs controlling defense gene networks. We identified a suite of WRKY TFs putatively controlling the plant response to chitin within 24hpi in tolerant hosts. Specifically, WRKY18, which contributes to Arabidopsis defense against the necrotroph Botrytis cinerea (Xu et al., 2006), was identified in our TF network. This suggests that WRKY18, along with additional WRKY TFs including WRKY 29, 53 and 54, may have evolved to play a regulatory role in mitigating attack from necrotrophic fungi. Thus, our predictive transcription factor network activated specifically in the tolerant cultivar provides a platform for future studies to uncover the role of WRKY TFs as master regulators of necrotrophic defense in B. napus and other crop species.

Following infection of tolerant B. napus, our data predict development of complex TF-DNA motif interactions that include ERF and MYC TFs shown to be downstream of JA signalling (Lorenzo et al., 2004; Niu et al., 2011). Among these TFs are homologues of MYC3, a bHLH TF that interacts with MYBs to activate glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (Schweizer et al., 2013). All three homologues of INDOLE GLUCOSINOLATE METHYLTRANSFERASE 5 detected in this study (BnaA07G33060D, BnaC06G37610D, and BnaC06G21620D) are co-expressed and predicted to be controlled through network interactions, offering novel insight into how glucosinolate production is transcriptionally controlled in response to S. sclerotiorum. Although the interactions remain putative, our network analyses provide an elegant and direct avenue for further investigation using functional characterization pipelines.

Global transcriptional reprogramming observed in tolerant leaf tissues, which expressed fewer genes following infection than the susceptible line provides evidence for genome-wide control of the genetic regulatory machinery following interaction with Sclerotinia. Enrichment of genes associated with DNA methylation controlled by TELEMORIC BINDING PROTEIN homologues in genes specifically expressed in ZY821, and higher accumulation levels of SET homologues hint at differences in how the two cultivars adjust chromatin and chemical modifications of genetic material in response to fungal infection. Since DNA methylation is essential to plant defense (Dowen et al., 2012), and transcriptional regulation of JA/ET genes requires the histone methyltransferase SET DOMAIN GROUP8 in Arabidopsis (Berr et al., 2010), epigenetic control mechanisms may directly contribute to tolerance to S. sclerotiorum.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced through the PTI pathway serve as important defense signalling molecules, but can also damage the host’s molecular machinery causing cell death (Scheler et al., 2013; Tripathy and Oelmüller, 2012). Within 24 hours of infection, at the leaf-fungal interface, we observed elevated redox buffering capacity in tolerant leaf tissues through genes contributing to oxidative stress and glutathione metabolic processes. Enzyme activity of APX and GR further validated gene expression data through the qualification of their small molecule substrates, ASC and GSH - critical components of the plant immune system (Foyer and Noctor, 2011; Ishikawa and Shigeoka, 2008). Interestingly, increased ASC at 24hpi in tolerant leaves does not correspond to transcript levels of VTC2, the rate-limiting enzyme in ASC biosynthesis. All VTC2 homologues were downregulated during infection in both genotypes, however transcript levels of ERF98, a positive regulator of ASC biosynthesis (Wang et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2012), were considerably higher in tolerant leaf tissues. These data further support our transcriptional circuit that places an ERF98 homologue, BnaA07G06750D, as a regulator of redox related defense processes, and provides novel insight into the transcriptional regulation of the complex networks underlying tolerance to S. sclerotiorum.

Activation of the ASC-GSH pathway in tolerant leaves of ZY821 likely contributes to the lack of cellular degradation observed in advance of fungal hyphae, thus limiting nutrient availability from OA-induced cell death (Kim et al., 2008). The importance of redox regulation and homeostasis in defense against S. sclerotiorum is further validated by the hyper-susceptible phenotype of vtc2 Arabidopsis. Delayed lesion growth in vtc2 plants at early infection stages is likely due to defense priming caused in part by the activation and nuclear localization of redox sensitive Nonexpressor of PR Genes 1 (NPR1), which transcriptionally activates PR1 and other defense regulators (Tada et al., 2008; Pavet et al., 2005). The vtc2 Arabidopsis plants constitutively express PR1 among other antimicrobial genes and accumulate phytoalexins at higher levels than wild-type plants (Colville et al., 2008), amounting to elevated defense capacities at the initial contact with the pathogen. Although this offers protection initially, inability to appropriately respond to S. sclerotiorum and buffer OA-induced ROS compromises defense over time, as seen in vtc2 plants infected with necrotrophic fungal pathogen Alternaria brassicola (Botanga et al., 2012). Taken together, we show that the coordination and functioning of cellular redox buffering systems at the host-pathogen interface has a profound role in the defense response against S. sclerotiorum, providing a physiological mechanism responsible for management of tissue damage and the tolerant phenotype of ZY821.

The current study presents a timely investigation into the transcriptional and physiological changes contributing to S. sclerotiorum tolerance in the ZY821 genotype directly at the site of infection at the host-pathogen interface of the leaf. While we have yet to fully understand the molecular underpinnings of S. sclerotiorum infection severity in B. napus or the full spectrum of genes required for genetic resistance, we have uncovered new molecular and physiological processes associated with tolerance at the first point of infection under real-world conditions. The wholesale transcriptional reprogramming undergone by plant cells infected with fungal pathogens is an intricately regulated process controlled through the activity of transcriptional circuits. This regulatory analysis highlighted the transcriptional control of redox response and highlights the critical nature of redox homeostasis for B. napus tolerance to S. sclerotiorum.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Clustered heatmap of all 1233 newly identified genes based on FPKM levels

Fig. S2. Heatmap of transcript levels in FPKM of all homologues of genes identified as circadian regulated in Arabidopsis (Covington et al., 2008).

Fig. S3. Dominant patterns of gene activity discovered using fuzzy k-means clustering analysis. Bar plots represent relative accumulation level of transcripts belonging to each pattern.

Fig. S4. Enzymatic and ascorbic acid (ASC) analysis. Enzyme activity levels of (A) monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDAR) and (B) dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR) from healthy and infected leaf tissues. (C) Levels of reduced ascorbate (ASC) and oxidized oxidized forms monodehyrdoascorbate (MDHA) and dehydroascorbate (DHA), and ASC redox ratio.

Fig. S5. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR of select genes. Relative fold changes from RNA-sequencing data are displayed as bars with qPCR levels as dots.

qPCR of selected transcripts

Table S1. Number of Illumina sequence reads that map to the Brassica napus genome.

Table S2. Number of Illumina sequence reads that map to the Sclerotinia sclerotiorum genome.

Table S3. Gene annotation and FPKM levels.

Table S4. Top 20 most highly abundant transcripts uncovered in the novel transcript discovery analysis.

Table S5. Gene Ontology summary.

Table S6. Transcript levels in FPKM of selected genes.

Table S7. Module tables.

Table S8. Fuzzy K means dominant patterns gene lists.

Table S9. Primer sequences used for quantitative reverse transcription PCR and genotyping of Arabidopsis mutants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. K. Rashid (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) for generously supplying the inoculum used for this study. This work was supported through a Manitoba Agriculture Rural Development Initiatives Growing Forward 2 and a Canola Agronomic Research Program (CARP) grant through Canola Council of Canada to M.F.B., T.D.K., and W.G.D.F. M.G.B was supported by a National Science and Engineering Research Council Vanier Scholarship and I.J.G. through a Manitoba Graduate Fellowship. S.L., C.T., and J.H. were supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101007) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471536).

References

- Amselem J, Cuomo CA, van Kan JA et al. 2001. Genomic analysis of the necrotrophic fungal pathogens Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. PLoS Genetics, 7, e1002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MG, Chan A, Mao X, Girard IJ, Lee S, Elhiti M, Stasolla C, Belmonte MF. 2014. Vitamin C deficiency improves somatic embryo development through distinct gene regulatory networks in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 5903–5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MG, Zhang X, Walker PL et al. 2017. Transcriptome analysis of the Brassica napus-Leptosphaeria maculans pathosystem identifies receptor, signaling and structural genes underlying plant resistance. The Plant Journal 90, 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MG, Walker PL, Pulgar-Vidal NC, Belmonte MF. 2017. SeqEnrich: A tool to predict transcription factor networks from co-expressed Arabidopsis and Brassica napus gene sets. PLoS ONE 12, e0178256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte MF, Kirkbride RC, Stone SL et al. 2013. Comprehensive developmental profiles of gene activity in regions and subregions of the Arabidopsis seed. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, E435–E444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmonte MF, Stasolla C. 2009. Altered HBK3 expression affects glutathione and ascorbate metabolism during the early phases of Norway spruce (Picea abies) somatic embryogenesis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry: PPB 47, 904–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berr A, McCallum EJ, Alioua A, Heintz D, Heitz T, Shen WH. 2010. Arabidopsis histone methyltransferase SET DOMAIN GROUP8 mediates induction of the jasmonate/ethylene pathway genes in plant defense response to necrotrophic fungi. Plant Physiology 154, 1403–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj AR, Joshi G, Kukreja B et al. 2015. Global insights into high temperature and drought stress regulated genes by RNA-Seq in economically important oilseed crop Brassica juncea. BMC Plant Biology 15, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller T, Felix G. 2009. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annual Review of Plant Biology 60, 379–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton MD, Thomma BP, Nelson BD. 2006. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary: biology and molecular traits of a cosmopolitan pathogen. Molecular Plant Pathology 7, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botanga CJ, Bethke G, Chen Z, Gallie DR, Fiehn O, Glazebrook J. 2012. Metabolite profiling of Arabidopsis inoculated with Alternaria brassicicola reveals that ascorbate reduces disease severity. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions: MPMI 25, 1628–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley CA, Lamey H, Endres GJ et al. 2006. Efficacy of fungicides for control of Sclerotinia stem rot of canola. Plant Disease 90, 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breusegem FV, Dat JF. 2013. Reactive oxygen species in plant cell death. American Society of Plant Biologists 141, 384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caarls L, Pieterse CM, Van Wees SC. 2015. How salicylic acid takes transcriptional control over jasmonic acid signaling. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cessna SG, Sears VE, Dickman MB, Low PS. 2000. Oxalic acid, a pathogenicity factor for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, suppresses the oxidative burst of the host plant. The Plant cell 12, 2191–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub B, Denoeud F, Liu S et al. 2014. Early allopolyploid evolution in the post-Neolithic Brassica napus oilseed genome. Science 345, 950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AC, Belmonte MF. 2013. Histological and ultrastructural changes in canola (Brassica napus) funicular anatomy during the seed lifecycle. Botany 91, 671–679. [Google Scholar]

- Chan AC, Khan D, Girard IJ, Becker MG, Millar JL, Sytnik D, Belmonte MF. 2016. Tissue-specific laser microdissection of the Brassica napus funiculus improves gene discovery and spatial identification of biological processes. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 3561–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaouch S, Queval G, Vanderauwera S, Mhamdi A, Vandorpe M, Langlois-Meurinne M, Van Breusegem F, Saindrenan P, Noctor G. 2010. Peroxisomal hydrogen peroxide is coupled to biotic defense responses by ISOCHORISMATE SYNTHASE1 in a daylength-related manner. Plant Physiology 153, 1692–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colville L, Smirnoff N. 2008. Antioxidant status, peroxidase activity, and PR protein transcript levels in ascorbate-deficient Arabidopsis thaliana vtc mutants. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 3857–3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington MF, Maloof JN, Straume M, Kay SA, Harmer SL. 2008. Global transcriptome analysis reveals circadian regulation of key pathways in plant growth and development. Genome Biology 9, R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denancé N, Sánchez-Vallet A, Goffner D, Molina A. 2013. Disease resistance or growth: the role of plant hormones in balancing immune responses and fitness costs. Frontiers in Plant Science 4, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does D, Leon-Reyes A, Koornneef A et al. 2013. Salicylic acid suppresses jasmonic acid signaling downstream of SCFCOI1-JAZ by targeting GCC promoter motifs via transcription factor ORA59. The Plant cell 25, 744–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen RH, Pelizzola M, Schmitz RJ et al. 2012. Widespread dynamic DNA methylation in response to biotic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 109, E2183–E2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando WGD, Nakkeeran S, Zhang Y, Savchuk S. 2007. Biological control of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary by Pseudomonas and Bacillus species on canola petals. Crop Protection 26, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. 2011. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiology 155, 2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg H, Atri C, Sandhu PS et al. 2010a. High level of resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in introgression lines derived from hybridization between wild crucifers and the crop Brassica species B. napus and B. juncea. Field Crops Research 117, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Garg H, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Barbetti MJ. 2013. Differentially expressed proteins and associated histological and disease progression changes in cotyledon tissue of a resistant and susceptible genotype of brassica napus infected with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS One 8, e65205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg H, Li H, Sivasithamparam K, Kuo J, Barbetti MJ. 2010. The infection processes of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in cotyledon tissue of a resistant and a susceptible genotype of Brassica napus. Annals of Botany 106, 897–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie KM, Ainsworth EA. 2007. Measurement of reduced, oxidized and total ascorbate content in plants. Nature Protocols 2, 871–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus DD, Rimmer SR. 2005. Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: when “to be or not to be” a pathogen?FEMS Microbiology Letters 251, 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horbach R, Navarro-Quesada AR, Knogge W, Deising HB. 2011. When and how to kill a plant cell: infection strategies of plant pathogenic fungi. Journal of Plant Physiology 168, 51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Buchenauer H, Han Q, Zhang X, Kang Z. 2008. Ultrastructural and cytochemical on the infection process of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in oilseed rape. Journal of Plant Diseases and Protection 115, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huot B, Yao J, Montgomery BL, He SY. 2014. Growth-defense tradeoffs in plants: a balancing act to optimize fitness. Molecular Plant 7, 1267–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Shigeoka S. 2008. Recent advances in ascorbate biosynthesis and the physiological significance of ascorbate peroxidase in photosynthesizing organisms. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 72, 1143–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamaux I, Gelie B, Lamarque C. 1995. Early stages of infection of rapeseed petals and leaves by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum revealed by scanning electron microscopy. Plant Pathology 44, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jurick WM 2nd, Rollins JA. 2007. Deletion of the adenylate cyclase (sac1) gene affects multiple developmental pathways and pathogenicity in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44, 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khot SD, Bilgi VN, del Río LE, Bradley CA. 2011. Identification of Brassica napus lines with partial resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Health Progress Online, doi:10.1094/PHP-2010-0422-01-RS [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Ridenour JB, Dunkle LD, Bluhm BH. 2011. Regulation of stomatal tropism and infection by light in Cercospora zeae-maydis: evidence for coordinated host/pathogen responses to photoperiod?PLoS Pathogens 7, e1002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Min JY, Dickman MB. 2008. Oxalic acid is an elicitor of plant programmed cell death during Sclerotinia sclerotiorum disease development. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions: MPMI 21, 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Ichihashi Y, Kimura S, Chitwood DH, Headland LR, Peng J, Maloof JN, Sinha NR. 2012. A High-Throughput Method for Illumina RNA-Seq Library Preparation. Frontiers in Plant Science 3, 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CX, Li H, Sivasithamparam K et al. 2006. Expression of field resistance under Western Australian conditions to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Chinese and Australian Brassica napus and Brassica juncea germplasm and its relation with stem diameter. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 57, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo O, Chico JM, Sánchez-Serrano JJ, Solano R. 2004. JASMONATE-INSENSITIVE1 encodes a MYC transcription factor essential to discriminate between different jasmonate-regulated defense responses in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 16, 1938–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mclean D. 1958. Role of dead flower parts in infection of certain crucifers by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary. Plant Disease Report 42, 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Zhang S. 2013. MAPK cascades in plant disease resistance signaling. Annual review of phytopathology 51, 245–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot N, Hausman JF, Hoffmann L, Evers D. 2005. Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 56, 2907–2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Figueroa P, Browse J. 2011. Characterization of JAZ-interacting bHLH transcription factors that regulate jasmonate responses in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2143–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CJ, Ronald PC. 2012. Cleavage and nuclear localization of the rice XA21 immune receptor. Nature Communications 3, 920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavet V, Olmos E, Kiddle G, Mowla S, Kumar S, Antoniw J, Alvarez ME, Foyer CH. 2005. Ascorbic acid deficiency activates cell death and disease resistance responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 139, 1291–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pinto MC, Locato V, De Gara L. 2012. Redox regulation in plant programmed cell death. Plant, Cell & Environment 35, 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Fiil BK, Petersen K et al. 2008. Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates gene expression through transcription factor release in the nucleus. The EMBO Journal 27, 2214–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheler C, Durner J, Astier J. 2013. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in plant biotic interactions. Current opinion in plant biology 16, 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluttenhofer C, Yuan L. 2015. Regulation of specialized metabolism by WRKY transcription factors. Plant Physiology 167, 295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer F, Fernández-Calvo P, Zander M, Diez-Diaz M, Fonseca S, Glauser G, Lewsey MG, Ecker JR, Solano R, Reymond P. 2013. Arabidopsis basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors MYC2, MYC3, and MYC4 regulate glucosinolate biosynthesis, insect performance, and feeding behavior. The Plant cell 25, 3117–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sønderby IE, Burow M, Rowe HC, Kliebenstein DJ, Halkier BA. 2010. A complex interplay of three R2R3 MYB transcription factors determines the profile of aliphatic glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 153, 348–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz HU, Guimaraes RL. 2004. Oxalate production by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum deregulates guard cells during infection. Plant Physiology 136, 3703–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada Y, Spoel SH, Pajerowska-Mukhtar K, Mou Z, Song J, Wang C, Zuo J, Dong X. 2008. Plant immunity requires conformational changes [corrected] of NPR1 via S-nitrosylation and thioredoxins. Science 321, 952–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi F, Yoshida R, Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Seo S, Yonezawa M, Maruyama K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. 2007. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade MKK3-MPK6 is an important part of the jasmonate signal transduction pathway in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 19, 805–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols 7, 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathy BC, Oelmüller R. 2012. Reactive oxygen species generation and signaling in plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior 7, 1621–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K, Somssich IE. 2015. Transcriptional networks in plant immunity. New Phytologist 206, 932–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhang Z, Huang R. 2013. Regulation of ascorbic acid synthesis in plants. Plant Signaling & Behavior 8, e24536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams B, Kabbage M, Kim HJ, Britt R, Dickman MB. 2011. Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathogens 7, e1002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Cai G, Tu J et al. 2013. Identification of QTLs for resistance to Sclerotinia stem rot and BnaC.IGMT5.a as a candidate gene of the major resistant QTL SRC6 in Brassica napus. PLoS One 8, e67740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhao Q, Yang Q, Liu H, Li Q, Yi X, Cheng Y, Guo L, Fan C, Zhou Y. 2016. Comparative transcriptomic analysis uncovers the complex genetic network for resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in Brassica napus. Scientific Reports 6, 19007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Shan L, He P. 2014. Microbial signature-triggered plant defense responses and early signaling mechanisms. Plant Science 228, 118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Chen C, Fan B, Chen Z. 2006. Physical and functional interactions between pathogen-induced Arabidopsis WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 transcription factors. The Plant Cell 18, 1310–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Srivastava S, Deyholos MK, Kav NNV. 2007. Transcriptional profiling of canola (Brassica napus L.) responses to the fungal pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Science 173, 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Kirkham MB. 1996. Antioxidant responses to drought in sunflower and sorghum seedlings. New Phytologist 132, 361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Wu Y, Gao M et al. 2012. Disruption of PAMP-induced MAP kinase cascade by a Pseudomonas syringae effector activates plant immunity mediated by the NB-LRR protein SUMM2. Cell Host & Microbe 11, 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Buchwaldt L, Rimmer SR et al. 2009. Patterns of differential gene expression in Brassica napus cultivars infected with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Molecular Plant Pathology 10, 635–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel C. 2014. Plant pattern-recognition receptors. Trends in Immunology 35, 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.