Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a highly successful human pathogen that has evolved in response to human immune pressure. The common USA300 methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains express a number of toxins, such as Panton-Valentine leukocidin and LukAB, that have specificity for human receptors. Using nonobese diabetic (NOD)–scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice reconstituted with a human hematopoietic system, we were able to discriminate the roles of these toxins in the pathogenesis of pneumonia. We demonstrate that expression of human immune cells confers increased severity of USA300 infection. The expression of PVL but not LukAB resulted in more-severe pulmonary infection by the wild-type strain (with a 30-fold increase in the number of colony-forming units/mL; P < .01) as compared to infection with the lukS/F-PV (Δpvl) mutant. Treatment of mice with anti-PVL antibody also enhanced bacterial clearance. We found significantly greater numbers (by 95%; P < .05) of macrophages in the airways of mice infected with the Δpvl mutant compared with those infected with the wild-type strain, as well as significantly greater expression of human tumor necrosis factor and interleukin 6 (84% and 51% respectively; P < .01). These results suggest that the development of humanized mice may provide a framework to assess the contribution of human-specific toxins and better explore the roles of specific components of the human immune system in protection from S. aureus infection.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, pneumonia, lung, respiratory, host-pathogen, humanized, mouse model, PVL, Panton-Valentine leukocidin

(See the editorial commentary Bamberger on pages 1346–8.)

Staphylococcus aureus is a well-recognized human pathogen associated with infection in diverse hosts; it is an important cause of healthcare-associated infection but also a major cause of morbidity and mortality in healthy patients with no factors predisposing them to infection. Nasal colonization with S. aureus is associated with subsequent infection and occurs in up to 30% of unselected individuals [1, 2]. Yet, despite the prevalence of S. aureus in the general population, the specific correlates of protective immunity against staphylococcal infection are not well defined.

A number of S. aureus virulence factors, including several bicomponent toxins, are specific for human receptors [3, 4]. One of the first of these human-specific toxins to be fully characterized was Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), which targets neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes [5, 6]. Although epidemiologically linked to severe infection in humans [7, 8], the PVL null mutant (lukS/lukF) did not consistently demonstrate the expected phenotype in murine models [5, 8–13], although it was significantly attenuated in rabbit models of pneumonia [5]. The molecular basis for this discrepancy was ascribed to the high human (and rabbit) specificity for the PVL receptors, C5aR and C5L2 [14]. Additional toxins, LukAB and HlgCB, have also been shown to have high specificity to the human forms of the receptors, CD11b and C5aR, respectively [4, 14, 15]. These toxins with human receptor specificity are in contrast to those such as α-toxin, which recognizes ADAM-10 on murine cells, as well as human cells [16].

The recognition that several potentially important staphylococcal toxins only target human cells is not surprising, given the evolution of S. aureus in response to the pressures imposed by the human immune system [17]. The recent development of humanized mice, SCID mice reconstituted with a human hematopoietic immune system [18], may provide the opportunity to address the significance of the human-specific staphylococcal toxins in the setting of a well-characterized murine model of infection. Particularly in the lung, the activation of multiple inflammatory signaling pathways by S. aureus often results in significant pathology. Exactly which immune cell types are involved and what their functions are in pulmonary defenses are difficult to establish, especially if certain leukocyte populations are targeted by human-specific S. aureus toxins. Recent studies suggest that the resident alveolar macrophage populations are especially important in orchestrating staphylococcal clearance [19], whereas dendritic cells [20] and even CD4+ T cells have not been found to be essential in murine models of pneumonia [21]. The human-specific bicomponent toxins PVL and LukAB have been associated with activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [22–24]. However, the relative contribution of these toxins among the many virulence factors expressed by the widespread methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain USA300 has not been evaluated.

In the studies described in this report, we addressed the impact of 2 bicomponent, human-specific toxins, PVL and LukAB, in the pathogenesis of S. aureus pneumonia. Our intent was to determine whether the availability of human receptors, as presented on the immune cells of humanized mice, increase susceptibility to USA300 pneumonia and the extent to which this contributes to pulmonary pathology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Please see the Supplementary Materials.

RESULTS

Humanized Mice Express Substantial Numbers of Human Leukocytes in Lung, Blood, and Bone Marrow

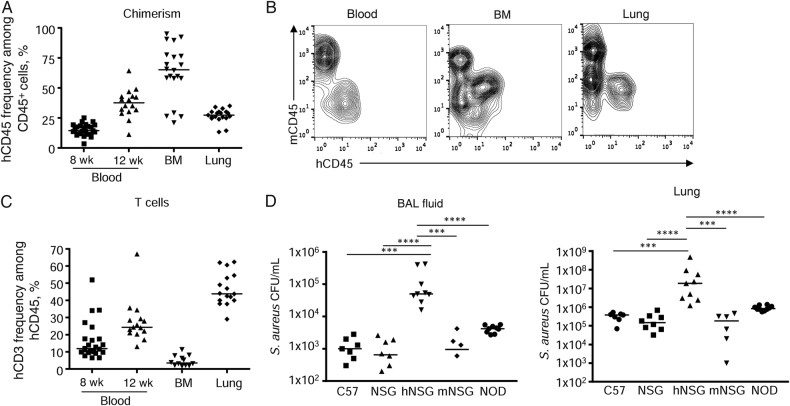

Mice expressing human immune cells that confer susceptibility to specific toxins, such as PVL, which targets the C5aR receptors, are expected to have increased susceptibility to S. aureus infection and more-severe pathological findings. To generate humanized mice, we used the nonobese diabetic (NOD)–scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) mouse that lacks B and T cells and functional natural killer (NK) cells and has defective myeloid cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) [18]. NSG mice were reconstituted with a human hematopoietic system through fetal hematopoietic stem cell (CD34+) and thymic tissue grafts [18]. At the time of infection, 12 weeks after transplantation, the humanized mice had on average 37% human chimerism (calculated as the percentage of hCD45+ cells among hCD45+ and mCD45+ cells) in the peripheral blood (Figure 1A and 1B). In the lung, human leukocytes represented 27% of all immune (CD45+) cells, while the bone marrow had higher levels, with 63% human chimerism (Figure 1A and 1B). Success of thymic engraftment was evident in CD3+ cell numbers (Figure 1C). CD3+ T cells composed 23% of the total human leukocyte population in peripheral blood. A total of 5% of lymphocytes in the bone marrow were human T cells, while the human lymphocyte population in the lung was 47% CD3+ cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Humanized mice are more susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nonobese diabetic (NOD)–scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice received human stem cells and underwent engraftment with thymus tissue before infection with S. aureus. A, Chimerism was analyzed by flow cytometry in the blood at 8 and 12 weeks and at 12 weeks in bone marrow (BM) and lung tissue. B, Examples of chimerism between mouse and human immune cells in blood, BM, and lung after 12 weeks of stem cell transfer and thymic engraftment. C, Thymus engraftment was assessed by the presence of T cells and analyzed by the presence of CD3+ T cells within the human CD45+ population. A and C, Data are from 4 independent experiments. D, Humanized (hNSG) and murinized (mNSG) mice 12 weeks after transfer and engraftment, as well as age-matched controls, were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus for 24 hours before bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed and lung tissue homogenized to determine bacterial numbers. Data are from 3 independent experiments. Each point represents a mouse. Two mNSG mice had bacteria below the detection level. Lines among data points represent median values. ****P < .0001 and ***P < .001. Abbreviations: hCD3, human CD3+ cells; hCD45, human CD45+ cells; mCD45, murine CD45+ cells.

Increased Severity of S. aureus Lung Infection in Humanized Mice

Having documented that a substantial proportion of the immune cells in the lung of the humanized mice were of human origin, we predicted that these mice would have more-severe infection than those lacking human immune cells. The capacity of C57BL/6J mice as a standard laboratory strain, humanized, murinized, nonhumanized NSG mice, and to control for the NSG background, NOD mice that lack the scid IL2Rγ mutation, to clear S. aureus USA300 pulmonary infection were quantified. Compared to C57BL/6J mice, humanized mice had 32-fold (0.012 × 105 vs 1.3 × 105 colony-forming units [CFU]/mL; P < .001) and 27-fold (0.033 × 107 vs 7.6 × 107 CFU/mL; P < .001) higher bacterial burdens in their airways and lung tissue, respectively (Figure 1D). Humanized mice also had significantly higher (40-fold in both the airway and lung) bacterial counts than nonhumanized NSG mice (BALF, 0.099 × 105 vs 1.3 × 105 CFU/mL; lung, 0.022 × 107 vs 7.6 × 107 CFU/mL [P < .0001]) and NOD control mice, with a 10-fold (P < .0001) higher number of CFU in the airway (0.042 × 105 vs 1.3 × 105 CFU/mL) and lung tissue (0.091 × 107 vs 7.6 × 107 CFU/mL; Figure 1D). Unlike the NSG mice, NOD mice are typically hyperglycemic at the age when infected, and therefore bacterial counts should be interpreted with this caveat [25]. To control for the process of humanizing the mice, we also generated murinized mice. These mice were reconstituted with murine bone marrow. The murinized mice had bacterial counts comparable to those of normal C57BL/6J mice (Figure 1D) and had significantly fewer bacteria in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and lung tissue (both P < .001) as compared to the humanized mice. These results suggest that the presence of human immune cells that are targeted by specific toxins confer increased susceptibility to S. aureus infection.

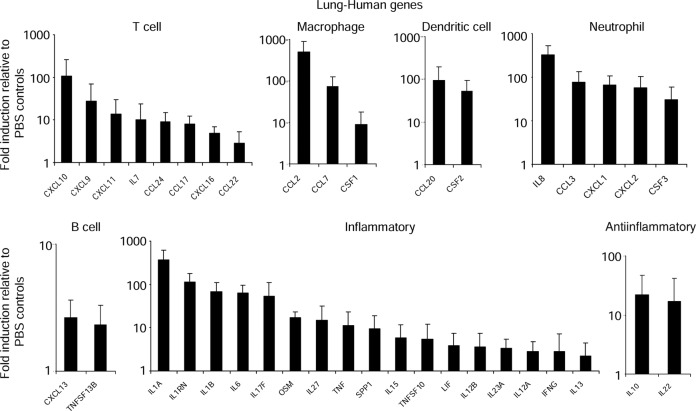

S. aureus Induce Human Cytokine Expression in Humanized Mice

To determine the extent of the participation of the human immune responses to S. aureus in the lung, human cytokine expression was analyzed using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction array (Figure 2). Robust human gene expression induced in response to infection was observed across several different categories. Several cytokines and chemokines associated with T cells were observed, including the CXCR3 chemokines and CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11. Over 400-fold induction of CCL2 was observed, in addition to genes encoding other macrophage chemokines, CCL7 and CSF1, consistent with the recruitment of macrophages into the airway (Figure 2). Genes associated with dendritic cells (CCL20 and CSF2), neutrophils (IL8, CCL3, CXCL1, CXCL2, and CSF3), and B cells (CXCL13 and TNFSF13B) were also observed (Figure 2). A large number of genes associated with inflammation were also induced upon infection. These included those encoding cytokines in the interleukin 1 (IL-1) family (IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1RN), interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin 17 (IL-17; Figure 2). We also observed induction of the antiinflammatory genes IL20 and IL22 (Figure 2). These data indicate there are sufficient human cells in the humanized mouse lung to induce robust human cytokine expression in response to S. aureus infection.

Figure 2.

Human cytokine gene expression in humanized mouse lungs in response to Staphylococcus aureus. Humanized mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus USA300 for 24 hours. RNA was extracted from lung tissue homogenate and a quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction array of various cytokines and chemokines, comparing uninfected and wild-type (WT) infected mice (n = 3 from 3 independent experiments). Abbreviation: PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

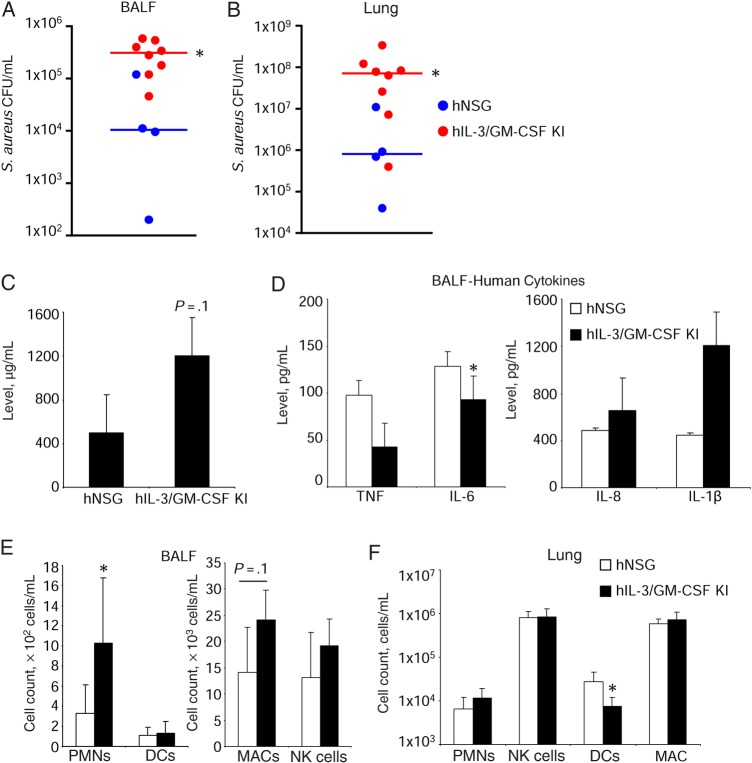

As further evidence that human immune cells confer increased susceptibility to infection in the humanized mouse, we used interleukin 3 (IL-3)/granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) knock-in mice. These mice express human IL-3 and GM-CSF and display improved myeloid cell reconstitution and the development of human alveolar macrophages [26]. There was an 8.8-fold increase (0.35 vs 3.1 × 105 CFU/mL; P < .05) of S. aureus in BALF in the knock-in mice, compared with the NSG humanized mice (Figure 3A), and a 285-fold increase in bacterial burden in the lung (0.32 × 107 vs 9.0 × 107 CFU/mL; P < .05; Figure 3B). This increased bacterial burden was associated with increased protein (as a measure of lung injury) in the BALF (Figure 3C). Human cytokine levels were not significantly different between the 2 groups of humanized mice (Figure 3D). We observed increased human neutrophil numbers in the IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice (3-fold; P < .05; Figure 3E), as well as an increase in human macrophages (1.7-fold; P = .1; Figure 3E), consistent with published data. No major changes were observed in the lung (Figure 3F). These experiments using the IL-3/GMCSF humanized mice also indicate that an increased number of human immune cells correlates with the increased severity of S. aureus infection.

Figure 3.

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)/interleukin 3 (IL-3) knock-in (KI) mice have increased susceptibility to Staphylococcus aureus infection as compared to nonobese diabetic (NOD)–scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) humanized mice. Humanized NSG and humanized IL-3/GM-CSF KI mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus USA300 for 24 hours. Bacterial counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (A) and lung homogenate (B). Each point represents a mouse. Lines among data points represent median values. C, Protein content in BALF. D, Human cytokine levels in BALF as assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Analysis of human immune cells in BALF (E) and lung homogenate (F). Data are for 4 humanized NSG and 8 IL-3/GM-CSF KI mice. Graphs display means with standard errors. *P < .05. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; MAC, macrophage; NK, natural killer; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell.

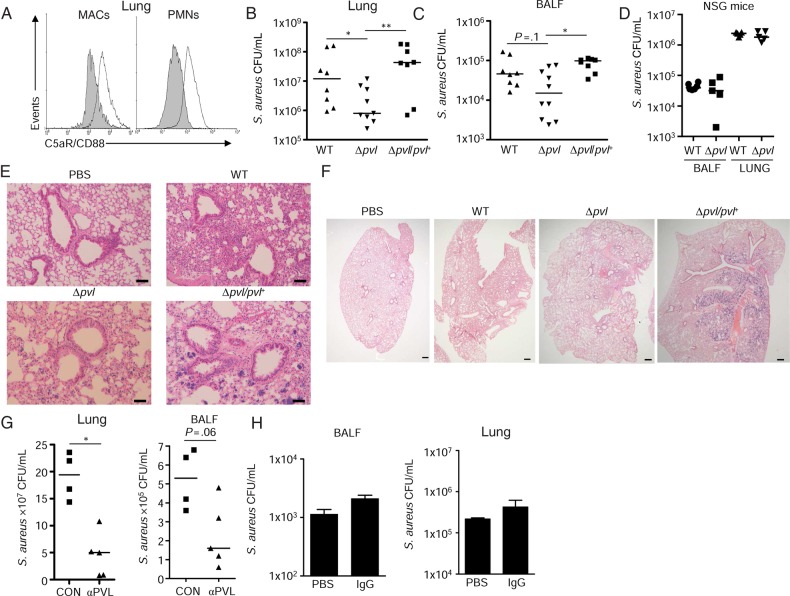

PVL Expression Contributes to the Pathogenesis of S. aureus Pulmonary Infection

We next examined the contribution of PVL to the pathogenesis of infection in the humanized mice, as several studies have demonstrated a lack of phenotype in the C57BL/6 background [12, 13, 27]. The presence of human immune cells expressing the PVL receptor C5aR [14, 28], as detected by flow cytometry (Figure 4A), should contribute to the pathology associated with infection caused by wild-type (WT) S. aureus but not by lukS-lukF (Δpvl) mutants. We infected the humanized mice with wild-type S. aureus USA300, a lukS/F-PV (Δpvl) mutant, and a complemented strain and observed that the Δpvl strain was cleared more efficiently (Figure 4B and 4C). Mice infected with the Δpvl mutant had 57% fewer bacteria in lung tissue (4.5 × 107 vs 0.32 × 107 CFU/mL; P < .05) than mice infected with WT S. aureus (Figure 4B). A similar trend in clearance was observed in the airway fluid (6.6 × 105 vs 2.8 × 105 CFU/mL; Figure 4C). The requirement for the human version of the PVL receptor was further evident when NSG, nonhumanized mice were infected with WT and Δpvl strains of S. aureus. There were no significant clearance differences in the airway or lung tissue between the strains in NSG, nonhumanized mice (Figure 4D). The improved clearance of the Δpvl mutant was evident in the substantially less lung consolidation and loss of alveolar airspaces than was associated with infection due to the WT USA300 or the complemented mutant (Figure 4E and 4F). Since there are additional S. aureus toxins that target the human C5a receptors [4], the contribution of PVL itself was confirmed by treating mice with a tetravalent bispecific PVL antibody, which was previously demonstrated to confer protection in a rabbit model of pneumonia [29], compared with mice treated with vehicle control. Mice treated with PVL antibody but not an IgG control had 76% fewer bacteria in the lung (1.9 × 108 vs 0.45 × 108 CFU/mL; P < .05) with a similar trend in the airway (5.3 × 105 vs 2.3 × 105 CFU/mL; Figure 4G and 4H).

Figure 4.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) participates in the pathogenesis of pneumonia in humanized mice. A, Expression of the PVL receptor C5a/CD88 on macrophages (MAC) and neutrophils (PMNs) isolated from lung tissue of humanized infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of Staphylococcus aureus USA300 or uninfected controls. Lung homogenate from control mice was stained with either isotype control (gray shading) or anti-CD88 antibody. Humanized mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus USA300, a Δpvl mutant, or a complemented strain (Δpvl/pvl+) for 24 hours. B and C, Bacterial counts in lung (B) and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) (C). D, Nonhumanized nonobese diabetic (NOD)–scid IL2Rγnull (NSG) mice were infected with 2 × 107 CFU of S. aureus USA300 or a Δpvl mutant for 24 hours. Each point represents a mouse. Lines among data points represent median values. Data are from 4 independent experiments. E and F, Hematoxylin-eosin staining of lung tissue, with an original magnification and scale bar of 100× and 50 μm, respectively (E) or 20× and 350 µm, respectively (F). G, Bacterial counts in lung tissue or BALF in mice infected after PVL antibody treatment. Each point represents a mouse. H, Bacterial counts in BALF and lung homogenate are shown from mice receiving vehicle control or immunoglobulin G (IgG; 10 mg/kg) 24 hours prior. **P < .01 and *P < .05. Abbreviations: CON, vehicle control; MAC, macrophage; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; WT, wild-type.

PVL Targets the Macrophage Population in Humanized Mice

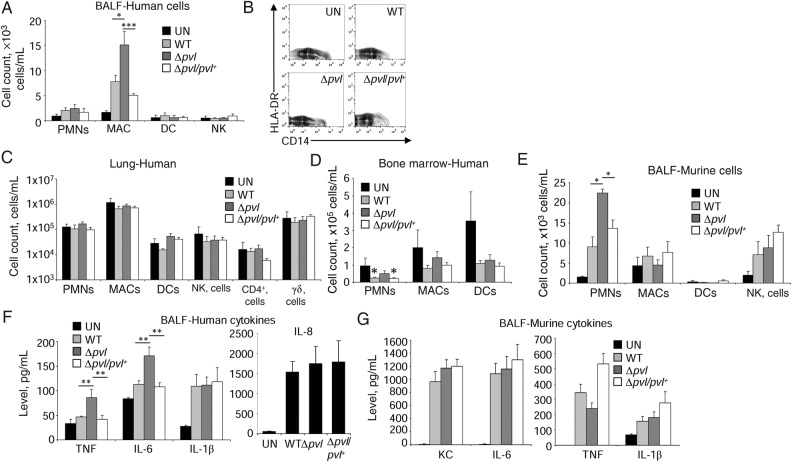

The types of human and murine immune cells recruited into the infected airways and lung tissue were characterized to determine whether PVL expression selectively targeted specific types of cells. The C5aR receptors are abundantly expressed on myeloid cells but not epithelial cells [30]. Infection with the Δpvl mutant resulted in 95% greater macrophage numbers in the BALF (P < .05; Figure 5A and 5B) as compared to WT infected mice, consistent with the expected PVL toxicity toward macrophages [6] but no difference in numbers of human neutrophils in the airway in WT and Δpvl S. aureus–infected mice (Figure 5A). No changes were observed in lung tissue (Figure 5C). There were slight decreases in human neutrophil numbers in the bone marrow in mice infected with PVL-expressing strains (Figure 5D). Substantially more murine neutrophils than human neutrophils were recruited into the lungs of the infected mice, and more murine neutrophils were found in the mice infected with the Δpvl mutant (Figure 5E), despite the presence of >105 human neutrophils/mL in the lung tissue and bone marrow (Figure 5C and 5D). There were no other significant differences in the types of murine immune cells recruited in response to infection. The improved clearance of the Δpvl strain was associated with greater amounts of human TNF (84% increase; P < .01) and IL-6 (51% increase; P < .01), but not IL-1β (Figure 5F) as compared to WT S. aureus–infected humanized mice. In contrast to the human cytokine response, we did not observe any differences in the murine cytokines examined in response to each of the bacterial strains (Figure 5G). Thus, the improved outcome from infection associated with the Δpvl strain correlated with the retention of greater numbers of macrophages within the airways and their local cytokine production.

Figure 5.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) reduces macrophage (MAC) numbers in humanized mice. Humanized mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of Staphylococcus aureus strains for 24 hours. A, Analysis of human immune cells in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). B, Representative contour plots of MAC populations from BALF of uninfected (UN) and S. aureus–infected mice. Human immune cells were quantitated by flow cytometry in homogenized lung tissue (C) or bone marrow (D). Data are from 4 independent experiments, with 4 UN mice, 10 each infected with wild-type (WT) or Δpvl strains, and 8 infected with Δpvl/Δpvl+ strains. E, Murine immune cells in BALF. Data are combined from at least 3 independent experiments, with 3 UN mice and 8 infected with S. aureus strains. F and G, Analysis of human (F) and murine (G) cytokines in BALF of infected humanized mice, using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are from 4 independent experiments, with 4 UN mice, 10 each infected with WT or Δpvl strains, and 8 infected with Δpvl/Δpvl+ strains. Graphs display means with standard errors. ***P < .001, **P < .01, and *P < .05. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; IL-1β, interleukin 1β; IL-6, interleukin 6; NK, natural killer; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

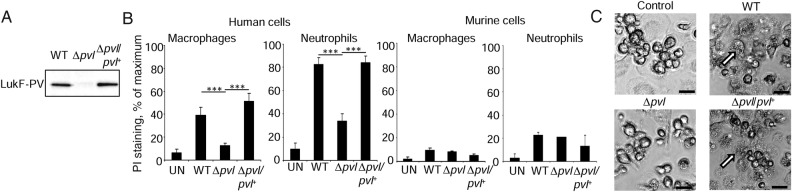

We confirmed the lytic effect of PVL on the human myeloid cells by differentiating human macrophages and neutrophils from the bone marrow of the humanized mice. Exposure of human macrophages and neutrophils to S. aureus culture supernatant (Figure 6A) harvested from WT but not Δpvl S. aureus led to significant increases in cell death, as indicated by propidium iodide staining (Figure 6B) and apparent lysis (Figure 6C). This was not evident with murine cells derived from humanized mice bone marrow (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) targets human immune cells. Bone marrow from humanized mice was differentiated into macrophages and neutrophils and incubated with Staphylococcus aureus (A) supernatants expressing PVL before staining with propidium iodide (PI; B). Results are from 2 independent experiments, with 4 uninfected (UN) mice, 6 each infected with wild-type (WT) or Δpvl, and 6 infected with Δpvl/Δpvl+. C, Microscopy of macrophages incubated with S. aureus supernatants. Examples of dead cells in WT and complemented wells are highlighted with white arrows. Scale bars indicate 20 µm. Graphs display means with standard errors. ***P < .001.

Expression of LukAB Does Not Contribute to S. aureus Lung Infection

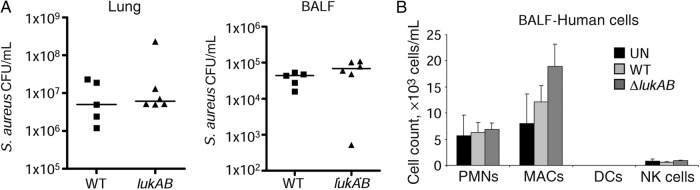

To confirm the hypothesis that the presence of human leukocytes confers susceptibility to the human-specific leukotoxins, we compared the clearance of WT and ΔlukAB MRSA. LukAB is a bicomponent S. aureus toxin with specificity for CD11b and targets human neutrophils [15], as well as monocytes/macrophages by activating NLRP3 [22] and inducing necroptosis [19]. Using the same model of infection in the Δpvl infection of humanized mice, we found no differences in the clearance of WT and lukAB MRSA or in the cell populations recruited (Figure 7A) or differences in the populations of human immune cells recruited to the lungs (Figure 7B). Thus, for LukAB, in contrast to PVL, its role in the pathogenesis of pneumonia does not correlate with the presence of human leukocytes in the humanized mouse model of infection.

Figure 7.

LukAB does not contribute to Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis in the humanized mouse model of pneumonia. Humanized mice were intranasally infected with 2 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU) of S. aureus USA300 or a lukAB mutant for 24 hours. A, Bacterial counts in lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). B, Analysis of human immune cells in BALF. Data are from 2 independent experiments. Each point represents a mouse. Lines among data points represent median values. Bar graphs display means with standard errors. Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; MAC, macrophage; NK, natural killer; PMN, polymorphonuclear cell; UN, uninfected; WT, wild-type.

DISCUSSION

S. aureus and especially MRSA is a major public health problem associated with tremendous morbidity and mortality, especially in select patient populations [28]. Despite ongoing intensive efforts, neither vaccines nor antistaphylococcal antibodies have proven effective in preventing S. aureus infection [31]. In many infectious diseases, murine models of infection have been exceptionally useful in defining both the bacterial and host factors critical to successful outcomes [32, 33], but their limitations, especially their resistance to S. aureus infection, is a well-recognized problem [33]. The recognition of human-specific receptors for PVL and other leukocidins, such as LukAB and HlgCB [3], has helped to explain why data generated from murine studies have not been fully applicable to humans. Our data suggest that the humanized mouse can provide insights into the importance of some of these human-specific toxins, and they provide insights into their targeting of specific human immune cells in the pathogenesis of acute pneumonia.

The severity of many USA300 pneumonias, particularly in light of the increased virulence of USA300 strains [34] and their production of several important toxins, led us to focus on USA300. The evolution of USA300 involved the acquisition of several genetic elements, including PVL [35], which has remained a controversial virulence factor, owing to its targeting of human cells and the lack of a suitable model to study it [5, 8–13]. Epidemiological studies in humans have suggested that PVL is linked to severe infection [7, 8, 36]. Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus strains also express human specific toxins, such as PVL, but at a lower overall rate [37], thus better understanding the role of PVL in infection is an important area of study. Our new data in the humanized mouse model support a role for PVL in the pathogenesis of S. aureus infection.

With the level of chimerism we achieved, the humanized mice were significantly more susceptible to S. aureus infection. These mice enabled us to observe an in vivo role for PVL in the pathogenesis of staphylococcal pneumonia and to identify the macrophage as a critical PVL target. Comparison of 2 different humanized mouse models, the NSG mouse model and the IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in model that supports human alveolar macrophage development [26], showed that increased severity of infection overall correlated with levels of human immune cells. However, just as there are substantial strain-specific differences in murine susceptibility to S. aureus infection, different mechanisms of human chimerization are likely to result in different outcomes from infection. Also, direct comparison of the immune response between these mice and humans is not possible because of the production of cytokines from both stromal and immune cells in humans. The humanized mice used in these studies, while having excellent reconstitution of T cells, monocytes, and macrophages, all of which are targets of S. aureus toxins [4, 14, 15, 19, 21], does not yet fully replicate a functioning human immune system. It has been recognized that neutrophil numbers are not optimal in the peripheral blood of humanized mice, and hence there may be a more limited number of cells to recruit; thus, this is an area to improve in subsequent models [38, 39].

Analysis of the immune response of the humanized mice to USA300 provided insights into the cell types that are critical in effective clearance of infection. While the importance of neutrophils in the response to S. aureus is well established, PVL targeting of macrophages correlated with the pulmonary pathology due to S. aureus infection, as has been demonstrated in other recent studies [19]. This is also consistent with recent studies that demonstrated that S. aureus induction of murine macrophage necroptosis in the early stages of pneumonia resulted in the loss of the immunomodulatory population of macrophages and contributed to the excessive inflammatory responses associated with S. aureus pneumonia [19]. Macrophages can play both proinflammatory and antiinflammatory roles and thus have many functions within the host [40]. Their loss can prevent proper bacterial clearance [19, 20], while their signaling cascades can contribute to inflammation and inefficient clearance [19]. Our results from the humanized mice suggest that human macrophages are especially susceptible to PVL-mediated lysis in vivo. Their loss is reflected in this model system by decreased expression of TNF and IL-6, as well as the impaired clearance of staphylococci from the airway. This increased cytokine production would aid in additional immune cell function, in addition to improved macrophage numbers to clear the bacteria in the absence of PVL. We did not observe a difference in human neutrophil numbers, possibly owing to their rapid replenishment as compared to alveolar macrophages. Bacterial clearance also did not correlate with human neutrophil numbers, but they did correlate with human macrophages, further confirming our recent observations in murine models of pneumonia that macrophages contribute to the modulation of the inflammatory response [19].

Despite the degree of chimerism we achieved, we did not observe a phenotype associated with the expression of LukAB, despite its known affinity for human CD11b. This may be explained by either additional targets that are recognized by this toxin, cellular targets not reconstituted in this model, and/or multiple conflicting effects of the LukAB/CD11b interaction. In a murine model of joint infection, LukAB and α-toxin were expressed together in biofilms, facilitating S. aureus growth and suppression of macrophage function [41], suggesting activity toward murine macrophages. However, single lukAB mutants have been shown to have a phenotype in a mouse renal abscess model [42] but not in models of bacteremia or rabbit skin and abscess formation [43]. LukAB is also recognized to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which can be associated with airway damage and decreased clearance of S. aureus [22, 44–46]. Thus, despite our increasing understanding of how these human toxins interact with their receptors, there are likely additional interactions that are highly relevant to human infection that remain to be identified.

Previous studies have used humanized mice to study different aspect of S. aureus pathogenesis. One study examined the role of PVL in skin infection. This study used a neonatal model of humanized mice, whereby pups are transferred with CD34+ cells without irradiation and thymic transplantation [47]. They too achieved high engraftment rates and saw a predominance of T lymphocytes over myeloid cells in the spleen. Subcutaneously infected humanized mice were more susceptible to infection, requiring a lower dose to achieve lesion sizes analogous to those in a standard C57BL/6J mouse [47]. Inactivation of PVL led to reduced lesion sizes but no changes in bacterial burden, and the nature of the immune cells involved in clearance was not defined. A sepsis study that relied on intraperitoneal injection observed increased mortality due to strain PS80 of S. aureus in humanized mice as compared to controls [48]. Like the previous study, this report also used neonatal mice that were transferred with CD34+ cells, but chimerism data do not exist for uninfected mice in various organs. This study demonstrated increased levels of T-cell activation, apoptosis, and Fas receptor expression in the humanized mice but did not identify a role for any human specific toxins [48]. Given the difficulties in development of an antistaphylococcal vaccine based on efficacy in murine models, these studies together suggest a potential role for humanized mice in predicting vaccine efficacy. Further studies to document adaptive and innate immune responses to S. aureus in the humanized mice may provide important insights into the nature of an effective immune response against this versatile pathogen.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at http://jid.oxfordjournals.org. Consisting of data provided by the author to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the author, so questions or comments should be addressed to the author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We wish to thank Nichole Danzl, for helpful discussions; Victor Torres, for the lukAB strain; and Dubravka Drabek, for the PVL antibody.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL079395 to A. P.) and the American Lung Association (to D. P.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Creech CB II, Kernodle DS, Alsentzer A, Wilson C, Edwards KM. Increasing rates of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005; 24:617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gorwitz RJ, Kruszon-Moran D, McAllister SK et al. Changes in the prevalence of nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2001–2004. J Infect Dis 2008; 197:1226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alonzo F III, Torres VJ. Bacterial survival amidst an immune onslaught: the contribution of the Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spaan AN, Vrieling M, Wallet P et al. The staphylococcal toxins gamma-haemolysin AB and CB differentially target phagocytes by employing specific chemokine receptors. Nat Commun 2014; 5:5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diep BA, Chan L, Tattevin P et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes mediate Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin-induced lung inflammation and injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:5587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loffler B, Hussain M, Grundmeier M et al. Staphylococcus aureus panton-valentine leukocidin is a very potent cytotoxic factor for human neutrophils. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6:e1000715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diep BA, Gillet Y, Etienne J, Lina G, Vandenesch F. Panton-Valentine leucocidin and pneumonia. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet 2002; 359:753–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Labandeira-Rey M, Couzon F, Boisset S et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin causes necrotizing pneumonia. Science 2007; 315:1130–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shallcross LJ, Fragaszy E, Johnson AM, Hayward AC. The role of the Panton-Valentine leucocidin toxin in staphylococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shallcross LJ, Williams K, Hopkins S, Aldridge RW, Johnson AM, Hayward AC. Panton-Valentine leukocidin associated staphylococcal disease: a cross-sectional study at a London hospital, England. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010; 16:1644–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Bae T, Otto M, Deleo FR, Schneewind O. Poring over pores: alpha-hemolysin and Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. Nat Med 2007; 13:1405–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Villaruz AE, Bubeck Wardenburg J, Khan BA et al. A point mutation in the agr locus rather than expression of the Panton-Valentine leukocidin caused previously reported phenotypes in Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia and gene regulation. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:724–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spaan AN, Henry T, van Rooijen WJ et al. The staphylococcal toxin Panton-Valentine Leukocidin targets human C5a receptors. Cell Host Microbe 2013; 13:584–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DuMont AL, Yoong P, Day CJ et al. Staphylococcus aureus LukAB cytotoxin kills human neutrophils by targeting the CD11b subunit of the integrin Mac-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:10794–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Inoshima I, Inoshima N, Wilke GA et al. A Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxin subverts the activity of ADAM10 to cause lethal infection in mice. Nat Med 2011; 17:1310–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thammavongsa V, Kim HK, Missiakas D, Schneewind O. Staphylococcal manipulation of host immune responses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2015; 13:529–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shultz LD, Brehm MA, Garcia-Martinez JV, Greiner DL. Humanized mice for immune system investigation: progress, promise and challenges. Nat Rev Immunol 2012; 12:786–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kitur K, Parker D, Nieto P et al. Toxin-induced necroptosis is a major mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus lung damage. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin FJ, Parker D, Harfenist BS, Soong G, Prince A. Participation of CD11c(+) leukocytes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clearance from the lung. Infect Immun 2011; 79:1898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parker D, Ryan CL, Alonzo F III, Torres VJ, Planet PJ, Prince AS. CD4+ T cells promote the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:835–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Melehani JH, James DB, DuMont AL, Torres VJ, Duncan JA. Staphylococcus aureus Leukocidin A/B (LukAB) Kills Human Monocytes via Host NLRP3 and ASC when Extracellular, but Not Intracellular. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1004970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holzinger D, Gieldon L, Mysore V et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin induces an inflammatory response in human phagocytes via the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Leukoc Biol 2012; 92:1069–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perret M, Badiou C, Lina G et al. Cross-talk between Staphylococcus aureus leukocidins-intoxicated macrophages and lung epithelial cells triggers chemokine secretion in an inflammasome-dependent manner. Cell Microbiol 2012; 14:1019–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peterson JD, Haskins K. Transfer of diabetes in the NOD-scid mouse by CD4 T-cell clones. Differential requirement for CD8 T-cells. Diabetes 1996; 45:328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Willinger T, Rongvaux A, Takizawa H et al. Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice support human alveolar macrophage development and human immune responses in the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bubeck Wardenburg J, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Otto M, Schneewind O, DeLeo FR. Panton-Valentine leukocidin is not a virulence determinant in murine models of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:1166–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bamberg CE, Mackay CR, Lee H et al. The C5a receptor (C5aR) C5L2 is a modulator of C5aR-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem 2010; 285:7633–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Laventie BJ, Rademaker HJ, Saleh M et al. Heavy chain-only antibodies and tetravalent bispecific antibody neutralizing Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:16404–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Klos A, Wende E, Wareham KJ, Monk PN. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. [corrected]. LXXXVII. Complement peptide C5a, C4a, and C3a receptors. Pharmacol Rev 2013; 65:500–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fowler VG, Allen KB, Moreira ED et al. Effect of an investigational vaccine for preventing Staphylococcus aureus infections after cardiothoracic surgery: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 309:1368–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buer J, Balling R. Mice, microbes and models of infection. Nat Rev Genet 2003; 4:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim HK, Missiakas D, Schneewind O. Mouse models for infectious diseases caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol Methods 2014; 410:88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Deleo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 2010; 375:1557–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Richardson AR. Virulence strategies of the dominant USA300 lineage of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012; 65:5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lina G, Piemont Y, Godail-Gamot F et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29:1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown ML, O'Hara FP, Close NM et al. Prevalence and sequence variation of panton-valentine leukocidin in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible staphylococcus aureus strains in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50:86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rongvaux A, Willinger T, Martinek J et al. Development and function of human innate immune cells in a humanized mouse model. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32:364–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ito R, Takahashi T, Katano I, Ito M. Current advances in humanized mouse models. Cell Mol Immunol 2012; 9:208–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hussell T, Bell TJ. Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scherr TD, Hanke ML, Huang O et al. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms Induce Macrophage Dysfunction Through Leukocidin AB and Alpha-Toxin. MBio 2015; 6:e01021–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dumont AL, Nygaard TK, Watkins RL et al. Characterization of a new cytotoxin that contributes to Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol 2011; 79:814–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Malachowa N, Kobayashi SD, Braughton KR et al. Staphylococcus aureus leukotoxin GH promotes inflammation. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1185–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cohen TS, Prince AS. Bacterial pathogens activate a common inflammatory pathway through IFNlambda regulation of PDCD4. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9:e1003682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kebaier C, Chamberland RR, Allen IC et al. Staphylococcus aureus alpha-hemolysin mediates virulence in a murine model of severe pneumonia through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:807–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Labrousse D, Perret M, Hayez D et al. Kineret(R)/IL-1ra blocks the IL-1/IL-8 inflammatory cascade during recombinant Panton Valentine Leukocidin-triggered pneumonia but not during S. aureus infection. PLoS One 2014; 9:e97546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tseng CW, Biancotti JC, Berg BL et al. Increased susceptibility of humanized NSG mice to Panton-Valentine leukocidin and Staphylococcus aureus skin infection. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1005292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Knop J, Hanses F, Leist T et al. Staphylococcus aureus Infection in Humanized Mice: A New Model to Study Pathogenicity Associated With Human Immune Response. J Infect Dis 2015; 212:435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Parker D, Martin FJ, Soong G et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA initiates type I interferon signaling in the respiratory tract. MBio 2011; 2:e00016–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Parker D, Planet PJ, Soong G, Narechania A, Prince A. Induction of type I interferon signaling determines the relative pathogenicity of Staphylococcus aureus strains. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10:e1003951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.