Summary

IFITM3 rs12252 was not associated with susceptibility to influenza-related critical illness or with disease severity outcomes in a multicenter cohort of US children admitted to the intensive care unit. Our data do not support rs12252 being a splice site.

Keywords: interferon-inducible transmembrane protein, IFITM3, pediatric, influenza, genetic susceptibility.

Abstract

Background.

Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) restricts endocytic fusion of influenza virus. IFITM3 rs12252_C, a putative alternate splice site, has been associated with influenza severity in adults. IFITM3 has not been evaluated in pediatric influenza.

Methods.

The Pediatric Influenza (PICFLU) study enrolled children with suspected influenza infection across 38 pediatric intensive care units during November 2008 to April 2016. IFITM3 was sequenced in patients and parents were genotyped for specific variants for family-based association testing. rs12252 was genotyped in 54 African-American pediatric outpatients with influenza (FLU09), included in the population-based comparisons with 1000 genomes. Splice site analysis of rs12252_C was performed using PICFLU and FLU09 patient RNA.

Results.

In PICFLU, 358 children had influenza infection. We identified 22 rs12252_C homozygotes in 185 white non-Hispanic children. rs12252_C was not associated with influenza infection in population or family-based analyses. We did not identify the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform in RNAseq data. The rs12252 genotype was not associated with IFITM3 expression levels, nor with critical illness severity. No novel rare IFITM3 functional variants were identified.

Conclusions.

rs12252 was not associated with susceptibility to influenza-related critical illness in children or with critical illness severity. Our data also do not support it being a splice site.

Identifying the role of host genetics in influenza susceptibility is paramount for designing effective methods for preventing and treating severe influenza virus infection. Members of the interferon-induced transmembrane (IFITM) protein family prevent influenza and other viruses such as dengue, Ebola, and West Nile from traversing the cell membrane [1]. Animal and in vitro data have confirmed that IFITM protein 3 (IFITM3) restricts influenza virus replication by preventing it from accessing the cytosol [2–4]. Despite growing data from animal models confirming the important role of IFITM3 in suppressing influenza infection [5, 6], confirmatory human data that IFITM3 variants influence influenza susceptibility or severity are contradictory.

IFITM3 rs12252_C was first identified as a risk allele for influenza disease severity by Everitt and colleagues. They reported that 3 of 53 white patients in the United Kingdom hospitalized with 2009H1N1 influenza during the pandemic were homozygous for the rs12252_C variant, a frequency that was higher than expected when compared with multiple control groups [4]. A large population dataset [7] reports that the rs12252_C allele is carried by only 8% (41/499) of Europeans. In contrast, carriage of the C allele in individuals with Hispanic, African, and East Asian ancestry is common with 3%, 7%, and 30% of individuals, respectively, predicted to be homozygous, potentially conferring high population-attributable risk. Three studies have identified an association between rs12252_CC homozygotes and influenza infection in adult cohorts. Zhang et al reported that rs12252_CC genotype was associated with influenza severity in Han Chinese [8]. Wang et al reported an increase in viral titers, inflammatory cytokines, and mortality in CC homozygotes in 16 Han Chinese patients infected with H7N9 influenza, a strain that has resulted in increased pathogenicity compared with seasonal influenza [9]. In contrast, Mills and colleagues were unable to replicate an association with rs12252_CC and severe influenza in a large mostly white multicenter cohort, although 2 of 232 patients with mild influenza were homozygous [10].

A mechanistic connection between IFITM3 rs12252_C and influenza disease has not been fully elucidated. Although it is a putative splice-site altering polymorphism proposed to encode an IFITM3 isoform (Δ21 IFITM3) lacking 21 amino acids at the amino terminus [4], the splice variant (ENST00000526811) was not detected in the HapMap lymphoblastoid cell lines with CC genotype [4]. Overexpression of full-length IFITM3 and Δ21 IFITM3 did show a difference in restriction of viral replication in A549 cells, however Williams and colleagues found that the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform effectively restricted entry of influenza H1, H3, H5, and H7 viruses and efficiently suppressed replication of H1N1 with an attenuated effect on H3N2 [11]. Additionally, the transcript support level in Ensembl (accessed 2 February 2017) [12] states that the alternate transcript is not currently supported by either messenger RNA or an expressed sequence tag (EST).

The aim of this study was to determine if the IFITM3 rs12252 variant was associated with influenza infection in a multicenter cohort of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with confirmed influenza-related critical illness. We also sought to identify additional relevant mutations, so we sequenced IFITM3 and evaluated linkage disequilibrium across identified variants. We evaluated rs12252 for association with influenza infection susceptibility and severity using family-based (parent-to-child transmission) and population-based approaches. We also assessed the genotype distribution of rs12252 in a second population of African American children with outpatient influenza infection. In addition, we used patient RNA to determine if rs12252 was a splice site in our populations.

METHODS

We prospectively enrolled children (age <21 years) across 38 Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network PICUs that voluntarily participated in the Pediatric Influenza (PICFLU) Genetic Susceptibility Study from November 2008 to April 2016. Patients presenting to the PICU with critical illness (acute respiratory failure and/or vasopressors) suspected of having an influenza infection (tested and/or influenza antivirals ordered) were eligible. We excluded those with immunosuppressive or severe underlying respiratory, metabolic cardiac, neurologic, or other condition(s) predisposing them to more severe illness. Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Data. We collected patient demographic and clinical data, flocked nasopharyngeal swabs, and endotracheal aspirates for additional viral testing, and samples from children (blood) and parents (saliva) for DNA extraction. The institutional review boards at each site approved the study and at least 1 parent gave informed consent. Parental genotypes were used as a family-based control group.

Influenza infection was confirmed by a positive viral test. Bacterial respiratory coinfection was defined as a clinical report of culture of an organism from the endotracheal, blood and/or pleural fluid within 72 hours of PICU admission with concomitant diagnosis by treating physicians. Severity of illness was assessed by Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III score. Additional definitions are in the Supplementary Data.

African American children from the FLU09 cohort (outpatients with polymerase chain reaction [PCR]–confirmed influenza infection) were included to enrich the number of subjects in this ethnic group and to control for influenza illness severity [13]. The 1000 Genomes Project database (http://www.1000genomes.org/) served as the population-based control group [7].

Genotyping and Gene Expression

Human IFITM3 sequences were amplified for probands using nested PCR. Analysis was performed using SeqScape version 2.5 analysis software (Applied Biosystems). We genotyped DNA from parents (rs12252, and variants rs1136853 and rs34481144 to create haplotypes) and PICU controls (rs12252) using TaqMan assays at a core facility. The Supplementary Data include additional details of sequencing and PICFLU and FLU09 genotyping methods. Total RNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 45 FLU09 influenza-infected patients who had mild to severe clinical outcomes. Quality and quantity of RNA samples were determined prior to their processing by RNA-seq. The concentration of RNA samples was determined using NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Scientific) and the integrity of RNA was determined by Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies). One microgram of total RNA was used as an input material for library preparation using TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit version 2 (Illumina). Size of the libraries was confirmed using Fragment Analyzer (Advanced Analytical Technologies) and their concentration was determined by quantitative PCR–based method using Library quantification kit (KAPA). The libraries were multiplexed and then sequenced on Illumina HiSeq2500 (Illumina) to generate 30M of single-end 50 base pair reads. FASTQ sequences were mapped to the human hg19 genome by a pipeline that employs STAR [14] and BWA [15]. Mapped reads were counted with HTSEQ [16] and gene-level fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) values were computed, and the data were log2 transformed. Exon junctions were extracted by mapping them to a combined database of known and potential exon junctions derived from Refseq, Aceview, and Ensembl annotations using an in-house pipeline. Quality control, statistical analyses, and visualizations were performed using Partek Genomics Suite 6.6 (St Louis, Missouri) and Stata MP/14.1 (College Station, Texas). From these samples, 44 were successfully genotyped for rs12252 and used for eQTL analysis. eQTL analysis for FLU09 RNAseq data was performed using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test in RStudio. Power was calculated using G*Power Version 3.1.9.2 [17] using α = .05 and effect size from the published GTEX rs12252 eQTL for IFITM3 in whole blood (www.gtexportal.org/home/; accessed 30 March 2017). For our sample size at the published effect size, we had 91% power to detect an association. Power remained >80% for our analysis even if the effect size was reduced to <0.5. RNA samples from PICFLU were assayed using the HuGene-1 st v1 array (Affymetrix, Mountain View, California). The CEL files were processed and splicing was analyzed using the ANOVA model in Partek Genomics Suite 6.6.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical variables were compared using χ2 test or Fisher exact tests and continuous variables with the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. Linkage disequilibrium among the IFITM3 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was evaluated with Haploview (www.broadinstitute.org) [18]. Allele frequencies of rs12252 varied by ethnic group in 1000 Genomes [7] (Supplementary Table 3). To minimize confounding by population substructure, we used a family-based analysis with transmission disequilibrium testing for the 3 principal SNPs using all subjects and white subjects. The software FBAT/PBAT [19, 20] (www.hsph.harvard.edu/fbat) was used to analyze the pedigrees using first the basic FBAT test and then HBAT to explore haplotype transmission (minimum informative families = 10) testing additive, dominant, and recessive models and PBAT to calculate the final transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) results and statistical power.

We used PLINK [21] (available at http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/) to explore the associations in PICFLU whites of the rs12252 IFITM3 SNP with the continuous phenotype of PRISM-III severity of illness score (untransformed and log-transformed) and with the dichotomous outcomes of mechanical ventilation, receipt of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), mortality, and acute lung injury. We also assessed whether rs12252 was associated with a clinical diagnosis of bacterial coinfection or type of influenza (A or B). Association was tested using the allele test.

RESULTS

We enrolled 393 children and included 358 (259 white) with a positive test for influenza virus from their respiratory tract in the PICFLU study. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients and the types of viral and bacterial infections identified. Severity of illness was high; 85% of children received some form of mechanical ventilator support for acute respiratory failure, 41% received vasoactive agents for cardiovascular support, and 6% of patients died.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Clinical Course, and Viral and Bacterial Pathogens Identified in Children Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit With Influenza Infection (N = 358)

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 144 (40.2) |

| Hispanic | 96 (26.8) |

| Race | |

| White | 259 (72.3) |

| African-American | 56 (15.6) |

| Asian | 14 (3.9) |

| Mixed or other | 29 (8.1) |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 6.4 (2.2–11.1) |

| Baseline health status | |

| Previously healthy | 222 (62.0) |

| Mild chronic respiratory | 99 (27.7) |

| Neurologic | 34 (9.5) |

| Other | 32 (8.9) |

| Support and complications | |

| Mechanical ventilation | |

| None | 54 (15.1) |

| Noninvasive only | 49 (13.7) |

| Endotracheal | 255 (71.2) |

| Acute lung injury/ARDS | 145 (40.5) |

| Shock plus vasopressors | 149 (41.6) |

| Extracorporeal life support | 44 (12.3) |

| PRISM score, median (IQR) | 5 (2–11) |

| PICU stay, d, median (IQR) | 6.4 (3.4–13) |

| Mortality | 22 (6.1) |

| Pathogen | |

| Respiratory-related bacterial pathogensa |

107 (29.9) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 66 (17.1) |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 29 (8.1) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 12 (3.3) |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | 9 (2.5) |

| Other | 41 (11.5) |

| Other virusesa | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 19 (5.3) |

| Adenovirus | 16 (4.5) |

| Rhinovirus | 37 (10.3) |

| Other noninfluenza virus | 28 (7.8) |

| Influenza type | |

| Influenza A | 291 (81.3) |

| A H3 | 63 (17.6) |

| A 2009 H1 | 151 (42.2) |

| A seasonal H1 | 13 (3.6) |

| A no subtype | 64 (17.9) |

| Influenza B | 65 (18.2) |

| Influenza A and Bb | 2 (0.5) |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; PICU, pediatric intensive care unit; PRISM, Pediatric Risk of Mortality.

aThirty-four patients had >1 noninfluenza viral and/or bacterial pathogen identified.

bOne patient had both influenza A and influenza B on repeated polymerase chain reaction testing and 1 had recently received influenza vaccine live, intranasally, but thought to be true infection.

IFITM3 rs1136853 and rs12252 were significantly out of Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the influenza-positive patients overall and in non-Hispanic whites (Table 2), with higher than expected rare homozygotes. However, comparisons of the distribution of PICFLU genotypes in the cases vs the 1000 Genomes European and control group did not reach significance. Carriage of the C allele is higher in African cohorts compared with whites in 1000 Genomes. As shown in Table 2, there was also no evidence of higher than expected rs12252_CC homozygotes in 56 African American children in PICFLU or in 54 African American children from the FLU09 study [13]. There was an increase in carriage of the rs34481144 A allele in PICFLU subpopulations compared to Europeans and Africans. Comparisons with the much smaller subset of individuals in 1000 genomes from US subpopulations included in European (n = 99 Utah Residents [CEPH] with Northern and Western European Ancestry [CEU]) and African (n = 61 Americans of African Ancestry in SW USA [ASW]) populations showed no significant differences for the variants (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 2.

Genotype Distributions for 3 IFITM3 Variants Compared to 1000 Genomes Project in Children With Influenza-Related Critical Illness (PICFLU) and Outpatient Pediatric Influenza Illness (FLU09)

| Cohort | SNP | Race | Total No. |

Major Allele, No. (%) |

Hetero-zygotes, No. (%) |

Minor Allele, No. (%) |

Hardy-Weinberg P Value |

Case-Control P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | AC | AA | ||||||

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | All | 358 | 335 (93.6) | 20 (5.6) | 3 (0.8) | .008 | … |

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | White non-Hispanic | 185 | 174 (94) | 9 (4.9) | 2 (1.1) | .02 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs1136853 | EUR | 503 | 474 (94.2) | 29 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | .54 |

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | AFR-Am | 56 | 50 (89.3) | 5 (8.9) | 1 (1.8) | .18 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs1136853 | AFR | 661 | 596 (90.2) | 61 (9.2) | 4 (0.6) | .09 | .63 |

| TT | CT | CC | ||||||

| PICFLU | rs12252 | All | 358 | 284 (79.3) | 62 (17.3) | 12 (3.4) | .002 | … |

| PICFLU | rs12252 | White non-Hispanic | 185 | 173 (93.5) | 10 (5.4) | 2 (1.1) | .02 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs12252 | EUR | 503 | 462 (91.8) | 41 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | .80 |

| PICFLU | rs12252 | AFR-Am | 56 | 31 (55.4) | 21 (37.5) | 4 (7.1) | 1.00 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs12252 | AFR | 661 | 363 (54.9) | 252 (38.1) | 46 (7) | .84 | .97 |

| FLU09 | rs12252 | AFR-Am | 54 | 34 (63) | 19 (35.2) | 1 (1.8) | .67 | .17 |

| GG | AG | AA | ||||||

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | All | 358 | 169 (47.2) | 142 (39.7) | 47 (13.1) | .06 | … |

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | White non-Hispanic | 185 | 44 (23.8) | 99 (53.5) | 42 (22.7) | .38 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs34481144 | EUR | 503 | 148 (29.4) | 245 (48.7) | 110 (21.9) | .65 | .001 |

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | AFR-Am | 56 | 42 (75) | 14 (25) | 0 (0) | .58 | Ref |

| 1000 Gen | rs34481144 | AFR | 661 | 605 (91.5) | 55 (8.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1.00 | <.001 |

1000 Gen indicates 1000 Genomes database (1000genomes.org), accessed 23 January 2017.

Abbreviations: AFR-Am, African American; AFR, African; EUR, European; PICFLU, Pediatric Influenza study; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

aAllelic test; P < .05 is highlighted in bold.

To identify rare variants with pathogenic potential, we sequenced IFITM3 in PICFLU patients. All variants identified are shown in Supplementary Table 2. There were no novel rare variants with pathogenic potential detected, nor were there any patients with rare homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the exons of IFITM3.

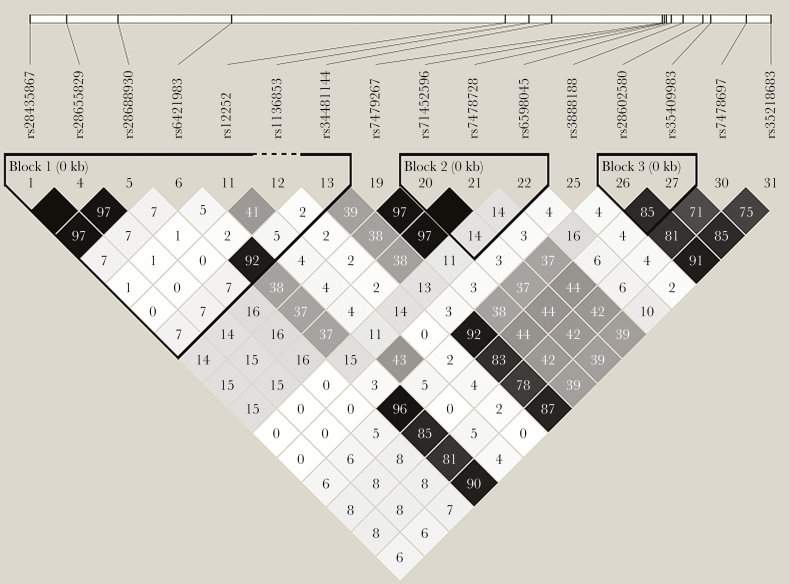

Using family-based analyses to control for potential confounding by racial stratification, we did not identify significant overtransmission of alleles from heterozygous parents for the 3 SNPs tested including rs12252_C (Table 3). Although there was a trend (P = .11 for rs12252, the trend was for increased transmission of the T allele. Power to detect an association at P < .05 was 100% for all models. Figure 1 shows the linkage disequilibrium among the SNPs identified in IFITM3. The 3 SNPs we evaluated were had high D’ but low r2 showing that some haplotypes were missing and consistent with the haplotypes identified using HBAT (distribution shown in Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, the rs12252_C allele was never carried with the rs34481144_A allele in parents or children in the PICFLU cohort. In addition, the 2 non-Hispanic individuals homozygous for the rare variant missense variant rs1136853_A were also homozygous for rs12252_C. With only 4 informative families, we lacked statistical power to test transmission of rs1136853AA in the recessive model (Table 3). Of note, the 2 haplotypes that include the rs12252_C allele were also not associated using HBAT analysis in the additive model (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Genotype and Phenotype Association Results for Family-Based Analyses Using PBAT

| Population | SNP | Allele | Frequency % | Familiesa | Model | Powerb | PBATP Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | A | 3.8 | 33 | Additive | 1.00 | .50 |

| PICFLU | rs12252 | C | 12.4 | 76 | Additive | 0.99 | .29 |

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | A | 34.4 | 146 | Additive | 1.00 | .56 |

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | A | 3.9 | 32 | Dominant | 1.00 | .33 |

| PICFLU | rs12252 | C | 12.4 | 69 | Dominant | 1.00 | .11 |

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | A | 34.4 | 113 | Dominant | 1.00 | .55 |

| PICFLU | rs1136853 | A | 3.9 | 4 | Recessive | 0.05 | .40 |

| PICFLU | rs12252 | C | 12.4 | 19 | Recessive | 1.00 | .45 |

| PICFLU | rs34481144 | A | 34.4 | 64 | Recessive | 1.00 | .08 |

| Whitec | rs1136853 | A | 3.9 | 25 | Additive | 1.00 | .18 |

| Whitec | rs12252 | C | 12.2 | 42 | Additive | 1.00 | .19 |

| Whitec | rs34481144 | A | 34.7 | 126 | Additive | 1.00 | .70 |

Abbreviations: PICFLU, Pediatric Influenza study; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

aFamilies with at least 1 heterozygous parent are included.

bThe probability that under binary outcome and modeling assumptions, the transmission disequilibrium test with this number of families would have detected a difference of α < .05, 2-sided.

cPICFLU cohort restricted to families self-identifying as white.

Figure 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (r2) in the white and influenza-positive subjects (n = 259) using a minor allele frequency of 0.01 as calculated by Haploview (www.broadinstitute.org) [18]. The following color scheme applies: white: r2 = 0; shades of gray: r2 = 0 to <1; black: r2 = 1. The r2 values are listed within each cell.

We were interested to examine whether the published association of rs12252_C carriage with increased disease severity in hospitalized Chinese populations extends to our predominantly white pediatric cohort. The phenotype analysis by allele for the rs12252 SNP in 259 white children did not reveal associations for higher carriage of the rs12252_C allele with PRISM severity of illness scores (untransformed P = .87; log-transformed P = .74). rs12252_C carriage was also not higher in the 73% of children who received mechanical ventilation (n = 188; odds ratio [OR], 1.1; P = .80), in the 13% who received ECMO support (n = 33; OR, 1.87; P = .13), or in the 16 children who died (OR, 0.38; P = .33). Diagnosis of acute lung injury (n = 110 [42.5%]; OR, 0.58; P = .12) or bacterial coinfection (n = 82 [32%]; OR, 0.84; P = .63) were not associated. There was no difference in allele distribution between 207 children (80%) with influenza A vs 52 (20%) with influenza B (OR, 1.03; P = .94).

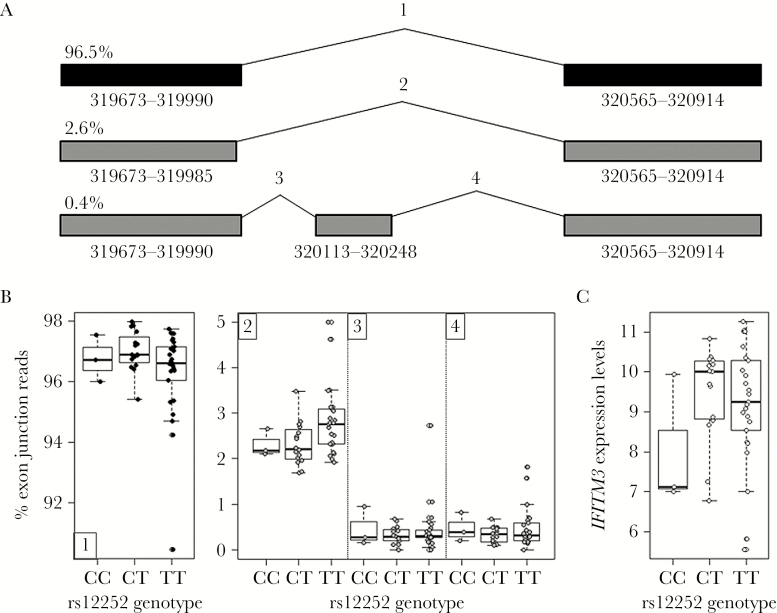

The lack of observed association of rs12252 in our critically ill predominantly white influenza cohort prompted us to examine whether a truncated RNA encoding the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform predicted by the rs12252 splice site variant could be detected in rs12252_CC carriers. We investigated RNAseq data from 44 influenza-infected patients from the FLU09 study for any evidence of the splice isoform. From this dataset, 3 individuals were homozygous for the C allele of rs12252. Despite having 3 homozygous individuals, the putative rs12252 splice isoform ENST00000526811 [4] was not observed (Figure 2). We did find a very small frequency of other isoforms represented in Figure 2, none of which were the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform (Figure 2). We also found no evidence of the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform in expression data from a subset of PICFLU patients (Supplementary Figure 2). These data show that in our cohorts we found no evidence for a functional consequence of rs12252 genotype on IFITM3 splicing, with the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform not detected and no eQTL association found (P = .25; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A, IFITM3 isoforms identified in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from the FLU09 cohort using RNAseq data. Each isoform is labeled with the percentage of normalized exon junction reads (counts per million) detected from only IFITM3 exon junction reads. Canonical full length IFITM3 comprised >96% of total IFITM3 exon junction reads. Coordinates for the exons are found below each exon with italicized coordinates indicating an alternative splice junction. Each splice junction is labeled with a number corresponding to the rs12252 genotype analysis below. B, Genotype analysis displays the percentage of exon junction reads (cpm) graphed by genotype of rs12252. Full-length IFITM3 (1) is graphed separately from the alternative splice junctions (2–4). The putative rs12252 splice isoform ENST00000526811 was not observed. C, IFITM3 expression levels measured by RNAseq (log2 [FPKM]) in PBMCs of influenza-positive individuals from the FLU09 cohort plotted based on genotype of rs12252 (P = .25).

DISCUSSION

Publications of genetic associations in existing cohorts of otherwise healthy, severely ill humans with influenza infection have been relatively small and results are inconsistent across cohorts, thus limiting conclusions about the role of host genetics [22]. Children have been particularly understudied, despite being an at-risk population. We sought to address this by developing the PICFLU cohort, a large representative group of US children with influenza-related critical illness without underlying conditions predisposing them to such severe infection. Collection of parental DNA allowed us to use both family- and population-based methods to evaluate potential gene–disease associations. The IFITM3 rs12252_C allele, previously reported as strongly associated with influenza susceptibility and/or severity in adults, was not associated with susceptibility for influenza critical illness in these children using a family-based analysis or with severity of illness within the cohort. This was also true for African American children, where carriage of the C allele is more common than in whites. In addition, we did not find evidence of the truncated RNA encoding the Δ21 IFITM3 isoform to support rs12252 as a splice site, suggesting that prior observed associations between rs12252 and influenza disease severity in adult populations may result from a yet undescribed mechanism.

Despite enrolling across a representative sample of US PICUs since 2008 and during the 2009 pandemic, our cohort of 358 children was mainly comprised of whites and has limited power to assess IFITM3 in multiple ethnic subgroups. Although our results were confirmed in a second pediatric African American outpatient population, we did not have sufficient numbers of Hispanic or East Asian patients to evaluate rs12252 where C is the major allele and homozygosity is common. In addition, the PICFLU cohort included only severe cases of influenza infection; we were not able to evaluate associations with milder cases. We report important linkage disequilibrium between rs12252 and rs34481144 in the IFITM3 gene; the C allele of the first SNP is not carried with the A allele of the second, indicating 2 possible risk haplotypes. In the 1000 Genomes Project database [7], the rs34481144_A allele is carried by 46.2% of Europeans whereas <1% of East Asians carry it (accessed 27 January 2017, 1000genomes.org).

Because the C allele of rs12252 is rare in individuals of European ancestry, homozygosity is even more infrequent, with none identified in 503 subjects from the 1000 genomes control population [7]. Most reported associations between rs12252 and influenza susceptibility in white cohorts have rested on identification of a small number of CC homozygotes in Europeans with influenza infection compared to few to none in larger population control cohorts. Everitt et al reported homozygosity in 3 of 53 adults hospitalized with 2009H1N1 [4]. In whites, Mills et al identified 2 in 259 with mild influenza vs 4 in 2623 controls [10]. López-Rodríguez et al found 1 in 58 individuals with mild influenza illness but zero in 60 patients with severe influenza infection [23]. We identified 2 rs12252_CC homozygotes in 185 white non-Hispanic children with influenza critical illness. Predicted to be even more uncommon, these 2 individuals were also homozygous for the rare minor allele of the IFITM3 H3Q rs1136853 missense mutation; however, it is predicted to be benign and upon stably induced challenge of influenza virus infected cell lines was indistinguishable from wild type [24]. Given the high level of admixture in the white population in the United States, we believe that use of parental genotype with family-based testing adequately controls for racial stratification. In a cohort with sufficient statistical power, we did not identify overtransmission of the rs12252_C allele from heterozygous parents in additive or recessive models. This evidence does not support rs12252_C homozygosity as a susceptibility genotype for severe influenza in white children, but we lacked sufficient power to test the rs1136853_A/rs12252_C homozygous genotype.

The PICFLU cohort is a major strength of this study. Children were enrolled across multiple large PICUs, diagnostic testing was rigorous, and extensive clinical phenotype information was collected. Influenza critical illness is not common in children without known risk factors for severe disease, enriching the cohort for genetic factors. In summary, we failed to confirm an association between the rs12252_C allele of IFITM3 and influenza susceptibility in 2 cohorts of children. Future studies in large clinically characterized cohorts with diverse ethnicities are important to better understand how genetics shapes the susceptibility to and severity of influenza infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

APPENDIX: PALISI PICFLU STUDY INVESTIGATORS

We acknowledge the hard work and collaboration of the following PALISI PICFLU Study Site Investigators who critically reviewed the initial study proposal and all modifications, and enrolled and collected data on the patients in this study: Children’s of Alabama, Birmingham (Michele Kong, MD, Kate Sewell, RN, BSN); Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Little Rock (Ronald C. Sanders, MD, Glenda Hefley, RN, MNsc); Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, Arizona (David Tellez, MD, Courtney Bliss, MS, Aimee Labell, MS, RN, Danielle Liss, BA, Ashely L. Ortiz, BA); Banner Children’s/Diamond Children’s Medical Center, Tucson, Arizona (Katri Typpo, MD, Jen Deschenes, MPH); Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, California (Barry Markovitz, MD, Jeff Terry, MBA, Rica Sharon P. Morzov, RN, BSN, CPN); Children’s Hospital Central California, Madera (Ana Lia Graciano, MD, Melita Baldwin, BS); UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, California (Heidi Flori, MD, Natalie Cvijanovich, MD, Becky Brumfield, RCP, Julie Simon, RN); Children’s Hospital of Orange County, Orange, California (Nick Anas, MD, Adam Schwarz, MD, Chisom Onwunyi, RN, BSN, MPH, CCRP, Stephanie Osborne, RN, CCRC, Tiffany Patterson, BS, CRC, Ofelia Vargas-Shiraishi, BS, CCRC); UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco, California (Anil Sapru, MD, Maureen Convery, BS, Victoria Lo, BA); Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora (Angela Czaja, MD, Peter Mourani, MD, Valeri Batara Aymami, RN, MSN-CNS, Susanna Burr, CRC, Megan Brocato, CCRC, Stephanie Huston, BS, RPSGT, CRC, Emily Jewett, Sandra B. Lindahl, RN, Danielle Loyola, RN, BSN, MBA, Yamila Sierra, MPH); Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Hartford (Christopher Carroll, MD, MS, Kathleen A. Sala, MPH, Sherell Thornton-Thompson, BA); Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, New Haven, Connecticut (John S. Giuliano Jr., MD, Joana Tala, MD); Holtz Children’s Hospital, Miami, Florida (Gwenn McLaughlin, MD); Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, Georgia (Matthew Paden, MD, Chee-Chee Manghram, Stephanie Meisner, RN, BSN, CCRP, Cheryl L. Stone, RN, Rich Toney, RN); Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Illinois (Bria M. Coates, MD, Avani Shukla); The University of Chicago Medicine Comer Children’s Hospital, Chicago, Illinois (Juliane Bubeck Wardenburg, MD, PhD, Andrea DeDent, PhD); Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville, Kentucky (Vicki Montgomery, MD, FCCM, Tracy Evans, RN, Kara Richardson, RN); Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Adrienne G. Randolph, MD, MSc, Anna A. Agan, MPH, Ellen M. Smith, BS, Ryan M. Sullivan, RN, BSN, CCRN, Grace Yoon, RN, NNP, Michael Kiers, RN, Shannon M. Keisling, BA); Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, Baltimore, Maryland (Melania Bembea, MD, MPH, Elizabeth D. White, RN, CCRP); Children’s Hospital and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis (Stephen C. Kurachek, MD, Angela A. Doucette, CCRP, Erin Zielinski, MS); St Louis Children’s Hospital, St Louis, Missouri (Allan Doctor, MD, Mary Hartman, MD, Rachel Jacobs, BA, Shivan Shetty, MPH); Children’s Hospital of Nebraska, Omaha (Edward Truemper, MD, Machelle Dawson, RN, BSN, MEd, CCRC); Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Daniel L. Levin, MD, J. Dean Jarvis, MBA, BSN); The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, New York (Chhavi Katyal, MD); Golisano Children’s Hospital, Rochester, New York (Kate Ackerman, MD, L. Eugene Daugherty, MD, Laurel Baglia, PhD); Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, Ohio (Ryan Nofziger, MD, FAAP, Healther Anthony, RN); Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital, Cleveland, Ohio (Steve Shein, MD, Ramon Adams, BA, Susan Bergant, Eloise Lemon, MSN, MHA, RN, CCRC, Lisa Petersen, RN, BSN); Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio (Mark W. Hall, MD, Kristin Greathouse, BSN, MS, Lisa Steele, RN, BSN, CCRN); Penn State Children’s Hospital, Hershey, Pennsylvania (Neal Thomas, MD, Jill Raymond, RN, MSN, Debra Spear, RN); Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Julie Fitzgerald, MD, Mark Helfaer, MD, Scott L. Weiss, MD, Jenny L. Bush, RNC, BSN, Mary Ann Diliberto, RN, Jillian Egan, RN, Brooke B. Park, RN, BSN, Martha Sisko, RN, BSN, CCRC); Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, Tennessee (Frederick E. Barr, MD, Judi Arnold, RN); Dell Children’s Medical Center of Central Texas, Austin (Renee Higgerson, MD, LeeAnn Christie, RN); Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, Texas (Marita Thompson, MD); Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston (Laura L. Loftis, MD, Nancy Jaimon, RN, MSN-Ed, Ursula Kyle, MS); University of Virginia Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville (Douglas F. Willson, MD, Christine Traul, MD, Robin L. Kelly, RN); Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee (Rainer Gedeit, MD, Briana E. Horn, Kate Luther, MPH, Kathy Murkowski, RRT, CCRC); Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (Philippe A. Jouvet, MD, Anne-Marie Fontaine, BSc); Centre Hospitalier de l’Université Laval, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada (Marc-André Dugas, MD).

Notes

Author contributions. A. G. R., W. K. Y., A. A. A., S. A. A., Y. Z., E. K. A., T. R. B., D. F., P. T., C. R., H. F., P. M., M. H., and H. S. all made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study, and the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data for this work. A. G. R., W. K. Y., A. A. A., S. A. A., and E. K. A. drafted the work and Y. Z., E. K. A., P. T., H. F., P. M., M. H., H. S., and C. R. revised it critically for important content. A. G. R., W. K. Y., A. A. A., S. A. A., Y. Z., E. K. A., T. R. B., D. F., P. T., C. R., H. F., P. M., M. H., and H. S. gave final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgments. We acknowledge the input of Jill Ferdinands, PhD, Influenza Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the early part of the study and Maikke B. Ohlson, PhD, for assisting with the FLU09 Study cohort genotyping.

Disclaimer. This work represents the findings of the authors and not necessarily the views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIH (AI084011 to A. G. R.); the CDC (contract to A. G. R.); DHHS (contract number HHSN272201400006C); St Jude Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (to P. G. T.); Genentech, Inc (to P. G. T., T. R. B., and C. M. R.); and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (to Y. Z. and H. C. S.). Sequencing reactions were carried out at the DNA Resource Core of Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (funded in part by the National Cancer Institute cancer center support grant 2P30CA006516-48).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Contributor Information

for the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network Pediatric Influenza (PICFLU) Investigators:

Michele Kong, Kate Sewell, Ronald C. Sanders, Glenda Hefley, David Tellez, Courtney Bliss, Aimee Labell, Danielle Liss, Ashely L. Ortiz, Katri Typpo, Jen Deschenes, Barry Markovitz, Jeff Terry, Rica Sharon P. Morzov, Ana Lia Graciano, Melita Baldwin, Heidi Flori, Natalie Cvijanovich, Becky Brumfield, Julie Simon, Nick Anas, Adam Schwarz, Chisom Onwunyi, Stephanie Osborne, Tiffany Patterson, Ofelia Vargas-Shiraishi, Anil Sapru, Maureen Convery, Victoria Lo, Angela Czaja, Peter Mourani, Valeri Batara Aymami, Susanna Burr, Megan Brocato, Stephanie Huston, Emily Jewett, Sandra B. Lindahl, Danielle Loyola, Yamila Sierra, Christopher Carroll, Kathleen A. Sala, Sherell Thornton-Thompson, John S. Giuliano, Jr., Joana Tala, Gwenn McLaughlin, Matthew Paden, Chee-Chee Manghram, Stephanie Meisner, Cheryl L. Stone, Rich Toney, Bria M. Coates, Avani Shukla, Juliane Bubeck Wardenburg, Andrea DeDent, Vicki Montgomery, Tracy Evans, Kara Richardson, Adrienne G. Randolph, Anna A. Agan, Ellen M. Smith, Ryan M. Sullivan, Grace Yoon, Michael Kiers, Shannon M. Keisling, Melania Bembea, Elizabeth D. White, Stephen C. Kurachek, Angela A. Doucette, Erin Zielinski, Allan Doctor, Mary Hartman, Rachel Jacobs, Shivan Shetty, Edward Truemper, Machelle Dawson, Daniel L. Levin, J. Dean Jarvis, Chhavi Katyal, Kate Ackerman, L. Eugene Daugherty, Laurel Baglia, Ryan Nofziger, Healther Anthony, Steve Shein, Ramon Adams, Susan Bergant, Eloise Lemon, Lisa Petersen, Mark W. Hall, Kristin Greathouse, Lisa Steele, Neal Thomas, Jill Raymond, Debra Spear, Julie Fitzgerald, Mark Helfaer, Scott L. Weiss, Jenny L. Bush, Mary Ann Diliberto, Jillian Egan, Brooke B. Park, Martha Sisko, Monroe Carell, Jr., Frederick E. Barr, Judi Arnold, Renee Higgerson, LeeAnn Christie, Marita Thompson, Laura L. Loftis, Nancy Jaimon, Ursula Kyle, Douglas F. Willson, Christine Traul, Robin L. Kelly, Rainer Gedeit, Briana E. Horn, Kate Luther, Kathy Murkowski, Philippe A. Jouvet, Anne-Marie Fontaine, and Marc-André Dugas

References

- 1. Bailey CC, Zhong G, Huang IC, Farzan M. IFITM-family proteins: the cell’s first line of antiviral defense. Annu Rev Virol 2014; 1:261–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell 2009; 139:1243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jia R, Xu F, Qian J et al. Identification of an endocytic signal essential for the antiviral action of IFITM3. Cell Microbiol 2014; 16:1080–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Everitt AR, Clare S, Pertel T et al. ; GenISIS Investigators; MOSAIC Investigators IFITM3 restricts the morbidity and mortality associated with influenza. Nature 2012; 484:519–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siegrist F, Ebeling M, Certa U. The small interferon-induced transmembrane genes and proteins. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2011; 31:183–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang D, Weidner JM, Qing M et al. Identification of five interferon-induced cellular proteins that inhibit West Nile virus and dengue virus infections. J Virol 2010; 84:8332–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Auton A, Brooks LD et al. ; 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015; 526:68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang YH, Zhao Y, Li N et al. Interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 genetic variant rs12252-C is associated with severe influenza in Chinese individuals. Nat Commun 2013; 4:1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Z, Zhang A, Wan Y et al. Early hypercytokinemia is associated with interferon-induced transmembrane protein-3 dysfunction and predictive of fatal H7N9 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:769–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mills TC, Rautanen A, Elliott KS et al. IFITM3 and susceptibility to respiratory viral infections in the community. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1028–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams DE, Wu WL, Grotefend CR et al. IFITM3 polymorphism rs12252-C restricts influenza A viruses. PLoS One 2014; 9:e110096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aken BL, Achuthan P, Akanni W et al. Ensembl 2017. Nucleic Acids Res 2017; 45:D635–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oshansky CM, Gartland AJ, Wong SS et al. Mucosal immune responses predict clinical outcomes during influenza infection independently of age and viral load. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 189:449–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013; 29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2015; 31:166–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39:175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:263–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laird NM, Horvath S, Xu X. Implementing a unified approach to family-based tests of association. Genet Epidemiol 2000; 19(suppl 1):S36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lange C, DeMeo D, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Laird NM. PBAT: tools for family-based association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2004; 74:367–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81:559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horby P, Nguyen NY, Dunstan SJ, Baillie JK. An updated systematic review of the role of host genetics in susceptibility to influenza. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013; 7(suppl 2):37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. López-Rodríguez M, Herrera-Ramos E, Solé-Violán J et al. IFITM3 and severe influenza virus infection. No evidence of genetic association. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 35:1811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. John SP, Chin CR, Perreira JM et al. The CD225 domain of IFITM3 is required for both IFITM protein association and inhibition of influenza A virus and dengue virus replication. J Virol 2013; 87:7837–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.