Hepatitis C virus reduces expression T-cell function by reducing a phosphatase (PTPRE) using an RNA-mediated mechanism. A related virus (yellow fever virus) also uses an RNA-mediated mechanism to reduce PTPRE and T-cell function while Zika virus does not.

Keywords: flavivirus, yellow fever virus, T-cell receptor, PTPRE, virus-derived short RNA

Abstract

The Flavivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family is comprised of many important human pathogens including yellow fever virus (YFV), dengue virus (DENV), and Zika virus (ZKV), all of which are global public health concerns. Although the related flaviviruses hepatitis C virus and human pegivirus (formerly named GBV-C) interfere with T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling by novel RNA and protein-based mechanisms, the effect of other flaviviruses on TCR signaling is unknown. Here, we studied the effect of YFV, DENV, and ZKV on TCR signaling. Both YFV and ZKV replicated in human T cells in vitro; however, only YFV inhibited TCR signaling. This effect was mediated at least in part by the YFV envelope (env) protein coding RNA. Deletion mutagenesis studies demonstrated that expression of a short, YFV env RNA motif (vsRNA) was required and sufficient to inhibit TCR signaling. Expression of this vsRNA and YFV infection of T cells reduced the expression of a Src-kinase regulatory phosphatase (PTPRE), while ZKV infection did not. YFV infection in mice resulted in impaired TCR signaling and PTPRE expression, with associated reduction in murine response to experimental ovalbumin vaccination. Together, these data suggest that viruses within the flavivirus genus inhibit TCR signaling in a species-dependent manner.

T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling is required to initiate T-cell responses to foreign antigens, and many viruses have evolved mechanisms to interfere with host T-cell function [1–3]. The Flaviviridae family is comprised of 4 genera: Hepacivirus, Pegivirus, Pestivirus, and Flavivirus. Prototype viruses for each genus include hepatitis C virus (HCV), human pegivirus (HPgV; previously called GB virus C), bovine viral diarrhea virus, and yellow fever virus (YFV), respectively. The Flavivirus genus includes many important human pathogens including YFV, Zika virus (ZKV), and dengue virus (DENV) [4], and ZKV and YFV recently emerged in the Americas and Africa [5–8].

HPgV and HCV dampen T-cell activation in vitro and in vivo at least in part by inhibiting TCR signaling [1, 9–11]. Incubation of T cells with HPgV virions, serum-derived vesicles, or recombinant envelope (E2) protein inhibits activation of the lymphocyte-specific Src kinase Lck [9, 10]. HCV also reduces proximal TCR signaling using 2 different mechanisms [1, 11]. HCV genomic RNA transferred into T cells by serum-derived virions and vesicles is sufficient to reduce TCR signaling. HCV genomic RNA is processed into virus-derived short RNAs (vsRNAs) [12] including an envelope (E2) coding vsRNA that targets and reduces expression of a Src-kinase regulatory phosphatase (protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon [PTPRE]) in vitro [1] and in vivo [11]. Reduction in PTPRE expression results in impaired Lck activation [1].

Because divergent viruses within the Flaviviridae inhibit TCR signaling, and YFV vaccination is associated with reduced response to subsequent heterologous vaccines [13, 14], we sought to determine if TCR inhibition is shared among flaviviruses. We found that YFV, but not ZKV or DENV, impaired TCR signaling. A YFV vsRNA derived from the envelope (env) coding RNA was sufficient to regulate TCR signaling, and targeted the same phosphatase (PTPRE) that HCV vsRNA targets, despite a lack of sequence homology between the viral sequences. Reduction of PTPRE expression impaired TCR signaling and enhanced YFV replication. Murine infection with YFV reduced interleukin 2 (IL-2) release following TCR engagement, and reduced PTPRE expression in tissues. This corresponded with a reduction in antigen-specific cytokine response following vaccination with ovalbumin. Together, these data identify a novel effect of YFV on TCR signaling and suggest that some viruses within the Flavivirus genus modulate T-cell function.

METHODS

See Supplementary Methods for more details.

Study Approval

Animal and human protocols were approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Review Board (IRB-01), respectively. All human participants provided written informed consent.

Cells

Jurkat cells expressing Lck (Jurkat E6.1) or not (JCAM 1.6), and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and murine splenocytes were prepared and maintained as described [15–17]. 293T, HepG2, Huh7, Huh7D (provided by Dr Dino Feigelstock), 293T HEK, BHK and Vero cells were maintained as described previously [1, 11, 15, 18, 19].

Viruses

YFV (17D; Sanofi), mumps virus (Jeryl Lynn strain; Merck), and ZKV (PR strain) were used in these studies. YFV, ZKV, and mumps virus replication was determined using either median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) or measuring viral RNA of cell culture supernatant fluids by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as described previously [16, 20, 21] (Supplementary Table 1). Viral titers correlated well between the 2 methods (supplementary figure 1A).

T-Cell Activation

PBMCs and Jurkat cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28 as described [1, 18]. Murine mononuclear cells were stimulated with antimurine CD3/CD28 antibody. TCR-mediated activation was determined by measuring human or murine IL-2 release by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as described previously [9, 10]. Lck and ZAP-70, PTPRE, YFV-ZKV-DENV env proteins were detected using immune blotting as described previously [1].

Small RNA Sequencing

Jurkat cell RNA was extracted from YFV-infected cells (3 days postinfection) or Jurkat cells stably expressing YFV env using mirVana miRNA Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentrations were determined by NanoDrop 1000, and RNA integrity determined by Agilent bioanalyzer. RNA libraries were generated from both samples using Truseq small RNA library preparation kit (Illumina), and purified cDNA libraries <200 nt in length were sequenced on the Illumina platform. Raw sequences were assembled and analyzed using SeqBuilder, and SeqMan Pro modules on Lasergene software (DNAStar).

Flavivirus Env Protein Expression

DENV serotype 2 env coding region (provided by Dr Lewis Markoff), YFV env coding region amplified from the infectious clone (17D strain, GenBank NC_002031 provided by Dr Charles Rice) [22, 23], and the ZKV env coding region was derived from infected cell–derived RNA. Env proteins were expressed in Tet-off Jurkat cells as described previously [1, 23, 24].

Murine Studies

C57BL/6N mice (Charles River Laboratories) were infected with 1 × 106 TCID50 YFV, or mumps virus intraperitoneally (IP). Mice were euthanized at indicated dates, and splenocytes, draining lymph nodes (LNs), and liver obtained for PTPRE analysis. Five mice were studied in each group and results describe 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Mice were inoculated IP with 200 μg of chicken egg ovalbumin (Grade V, Sigma) mixed with 50 μL of alum (Imject Alum, Invitrogen) in 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline (final volume) 7 and 14 days following YFV or mumps virus infection. Cells from the draining LNs and spleen were cultured with ovalbumin (1–2 × 105 cells per well) for 72 hours, and supernatants analyzed for ovalbumin-specific cytokines (IL-2, interferon gamma [IFN-γ], interleukin 13 [IL-13], interleukin 5 [IL-5]) as described previously [18].

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed using GraphPad software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software Inc). Analysis of variance was used to determine differences in viral replication kinetics. Two-sided t tests were used to compare results between test and controls on specific days postinfection. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Flavivirus T-Cell Replication and Envelope RNA Expression Effects on TCR Signaling

YFV replicates in transformed T-cell lines and PBMCs [16]; however, ZKV T-cell replication has not been described. We found that YFV, ZKV, and mumps virus replicated in a CD4+ T-cell line (Jurkat) (Figure 1A). Mumps was used as an RNA nonflavivirus control because, unlike ZKV, it infects wild-type mice [25].

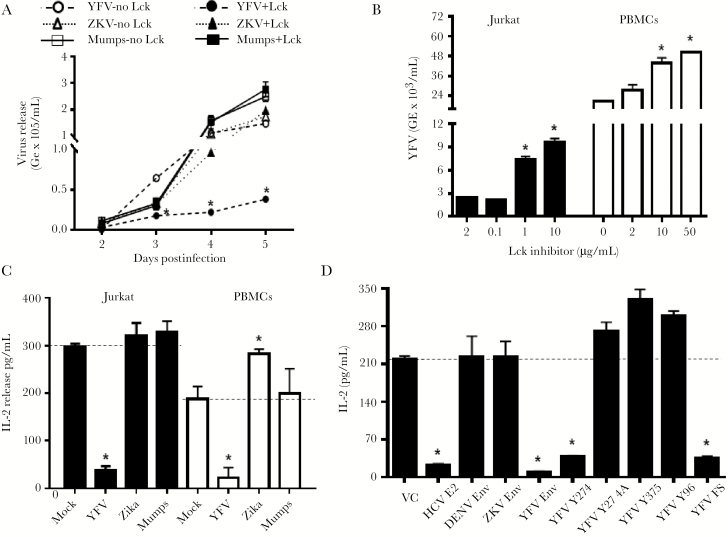

Figure 1.

Flavivirus replication and envelope (env) expression in resting and activated T cells. Yellow fever virus (YFV) replication was greater in Jurkat cells lacking Lck, whereas Zika virus (ZKV) and mumps virus replication was similar in Jurkat cells with and without Lck (A) (P < .01 analysis of variance; *P < .01 t test on individual days postinfection). Inhibition of Lck function with Lck inhibitor II prior to infection enhanced YFV replication in Jurkat cells and primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (B) in a dose-dependent manner. Infection of Jurkat cells and PBMCs with YFV reduced interleukin 2 (IL-2) release compared to uninfected cells (mock) following anti-CD3/CD28 whereas ZKV and mumps virus infection did not reduce IL-2 release (C). YFV and mumps virus multiplicity of infection was 0.5 and data represent IL-2 levels in culture supernatant fluids 5 days postinfection. IL-2 release 24 h post–TCR stimulation in Jurkat cell lines stably expressing the plasmid vector control (VC), hepatitis C virus envelope 2 protein (HCV E2), dengue virus serotype 2 envelope (DENV env), Zika virus envelope (ZKV env), and the YFV envelope (YFV env) proteins and frameshift expressing YFV env RNA without protein (D). GE indicates genomic equivalents. *P < .01 compared to control. All data represent averages (± standard error of the mean) of 3 independent experiments.

YFV replication was reduced in Jurkat cells expressing the lymphocyte-specific Src-kinase (Lck, Jurkat E6.1) [26] compared to Jurkat cells lacking Lck (JCaM1.6). In contrast, Lck expression did not affect ZKV or mumps virus replication (Figure 1A). Activation of Jurkat cells with anti-CD3/CD28 24 hours prior to YFV infection significantly reduced viral replication in Jurkat cells expressing Lck, but not in the Lck-negative Jurkat cells (supplementary figure 1B). TCR stimulation did not affect ZKV or mumps replication in Jurkat cells (not shown). YFV replication in Jurkat and PBMCs increased when Lck function was inhibited using a Lck-specific inhibitor II (Figure 1B), and YFV inhibited TCR-mediated IL-2 release (Figure 1C). Together, these data suggest that T-cell activation interferes with YFV, but not ZKV or mumps virus replication, and that TCR signaling through Lck is required for this inhibition.

HPgV E2 sequences contain conserved amino acids predicted to serve as Lck substrates [1, 10], and TCR-mediated Lck activation is inhibited by expression of HPgV E2 protein in Jurkat cells [1, 9, 10]. Examination of ZKV, YFV, and DENV envelope sequences identified 8 conserved tyrosine residues in the ZKV env (GenBank KX198135), 2 in YFV (17D) env (GenBank NC_003021), and 1 tyrosine in the DENV serotype 2 env (GenBank L10055.1) predicted to be Lck substrates [27].

Jurkat cell lines stably expressing ZKV, YFV, or DENV 2 env proteins were generated as described [10, 23] and env expression confirmed (representative data shown in supplementary figure 2A and 2B). YFV, but not ZKV or DENV2 envelope expression reduced IL-2 release in Jurkat cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 compared to the vector control (Figure 1D). Jurkat cell lines were generated expressing predicted YFV env Lck substrate peptide regions (Y274, Y375), or a peptide predicted to be a different Src-kinase (Fyn Y96) substrate (schematic in supplementary figure 2C). Cell lines expressing a Y274A substitution and the YFV env coding region with a frameshift mutation to abolish translation were also generated. Following TCR stimulation, IL-2 release was lower in cells expressing the YFV env protein and RNA without protein sequence, and the Y274 peptide, but not in cells expressing the Y375 peptide or the Fyn substrate Y96 peptide (Figure 1D).

Upon TCR engagement, Lck activation is initiated by dephosphorylation of tyrosine 505 (Y505) resulting in subsequent Lck-mediated autophosphorylation in trans at position Y394 [26]. Consistent with the IL-2 release data, Lck activation was reduced by YFV env (supplementary figure 3). Activated Lck phosphorylates ZAP-70 at Y319, and YFV env reduced phosphorylation of ZAP-70 Y319 following TCR engagement (supplementary figure 3). Thus, YFV env RNA impaired TCR-mediated IL-2 release.

YFV RNA Reduces Expression of the Src Kinase Regulatory Phosphatase PTPRE

Structural prediction of the YFV env indicates that it is a target for cellular RNA-exonuclease cleavage (supplementary figure 4A) [28], and suggests that YFV RNA regulates TCR via an RNA-based mechanism. The YFV RNA sequence coding the env Y274 peptide that inhibited TCR signaling (Figure 1D) was examined for complementary sequences with cellular genes. Two sites within the 3ʹ-UTR of a Src-kinase activating phosphatase (PTPRE) had considerable complementarity with this sequence (Figure 2A). PTPRE regulates Src-kinase signaling through the adaptor protein Grb2 [11, 29, 30], and Grb2 deficient T cells have impaired Lck activation [30]. Of note, PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR is also targeted by HCV E2 vsRNA [1] despite no sequence homology with the YFV vsRNA sequence (supplementary figure 4B). PTPRE mRNA was not reduced in Jurkat cells expressing YFV env RNA (data not shown); however, protein expression was reduced in these cells (Figure 2B). PTPRE was restored when the YFV env RNA was expressed with a Y274A substitution, but not Y274F. Y274F contains a single RNA base change (A to U) whereas Y274A has 2 changes (UA to GC; Figure 2B) within the RNA sequence complementary to the PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR (Figure 2A).

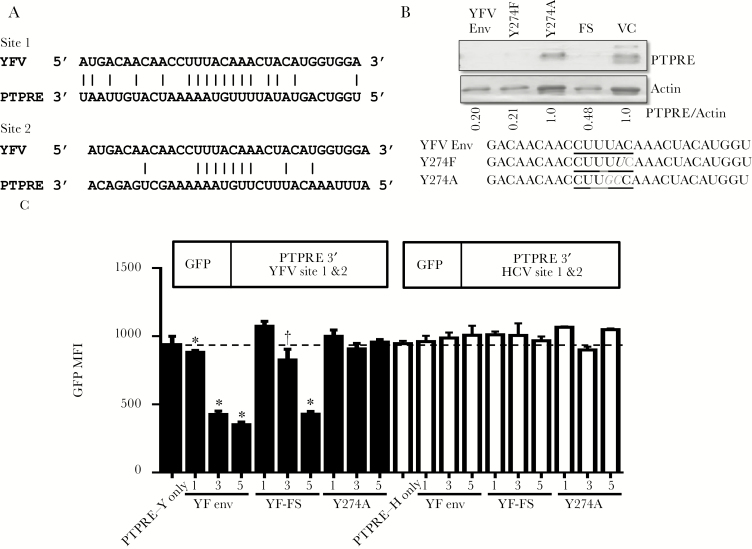

Figure 2.

Yellow fever virus (YFV) env RNA expression specifically regulates protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon (PTPRE) expression. YFV Y274 peptide coding sequence aligned with 2 sites on the 3ʹ-UTR of PTPRE (A). PTPRE expression in Jurkat cells expressing YFV env, YFV env with Y274F or Y274A substitutions, or the YFV env coding RNA with a frameshift to abolish protein translation (YFV-FS) (B). PTPRE expression was normalized using actin. The mutations introduced into the Y274 env RNA to generate amino acid mutations are underlined (B). To determine if YFV env RNA targets PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR sequences, HEK 293T cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding GFP with either the YFV PTPRE 3ʹUTR target site 1 and site 2 sequence or the HCV PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR site 1 and site 2 sequence. GFP expression in cells transfected with the GFP-PTPRE plasmids alone, or co-transfected with various concentrations of plasmid DNA encoding YFV native env, YFV env frameshift (with no protein translation; YFV-FS) or the Y274A mutant env were examined 72 h posttransfection (C). Data represent the averages (± standard error of the mean) of 3 independent transfection experiments. * P < .01; †P < .05. Abbreviations: FS, frameshift; GFP, green fluorescent protein; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MFI, mean fluorescent intensity; PTPRE, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon; VC, vector control; YFV, yellow fever virus.

To validate that PTPRE regulation required the 3ʹ-UTR RNA sequences, chimeric green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression plasmids containing either the YFV or HCV E2 PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR target sequences were constructed (Figure 2C) [1]. Following transient transfection of YFV env and GFP-PTPRE in HEK 293T cells, GFP expression was reduced in cells co-expressing the YFV env RNA in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C). In contrast, GFP was not reduced by co-transfection with the Y274A plasmid. YFV env RNA did not regulate GFP gene expression when PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR sequences targeted by HCV E2 were placed after GFP (Figure 2C). Transfection efficiency was not different in any of the transfected cells (supplementary figure 5).

YFV and ZKV replicated to higher levels in CD3+ enriched primary PBMCs than in bulk PBMCs (supplementary figure 6A and B), but only YFV regulated PTPRE 4 days postinfection (Figure 3A; supplementary figure 6C). Of note, anti-CD3 was not included in the media as it was in supplementary figure 1B. Cell viability was similar in YFV, ZKV, and mumps-infected cells (supplementary figure 6D). These data suggest that T cells support YFV replication to a greater extent than other PBMC cell populations, since an equal number of PBMCs and CD3+ enriched cells were infected. Three or more days of YFV infection was required to reduce PTPRE expression by >50% (supplementary figure 6C).

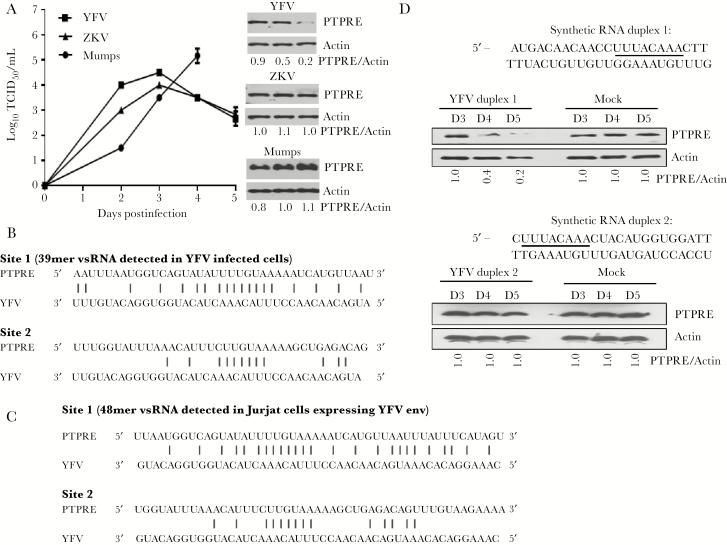

Figure 3.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon (PTPRE) is regulated by yellow fever virus (YFV) infection and synthetic YFV RNA sequences, and short YFV RNAs are generated during YFV infection of Jurkat cells. Replication of YFV, Zika virus (ZKV), and mumps virus in HepG2 cells (A). YFV, but not ZKV or mumps virus, regulated PTPRE expression 4 days postinfection (A). Using next-generation sequencing, YFV short RNA sequences were detected 3 days postinfection in Jurkat cells (B) and in Jurkat cells stably expressing YFV env RNA sequences (C). The level of complementarity with PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR target sites 1 and 2 are shown. HEK cells were transfected with synthetic YFV sequence duplex RNAs with the putative seed sequence (underlined) at the 3ʹ end (D) (YFV RNA duplex 1) or the 5ʹ end of the YFV sequence (YFV RNA duplex 2). PTPRE expression was reduced in cells transfected with RNA duplex 1 on days 4 and 5 posttransfection, but not by RNA duplex 2 (D). PTPRE expression was normalized to actin measured on the day of transfection (PTPRE/Actin). Abbreviations: PTPRE, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon; TCID50, median tissue culture infective dose; YFV, yellow fever virus; ZKV, Zika virus.

To determine if YFV env RNA sequences were sufficient to regulate PTPRE, synthetic duplex sequences were transfected into 293 HEK cells. The putative YFV “seed” sequence was placed at either the 3ʹ end (vsRNA duplex 1) or the 5ʹ end of the synthetic RNA (vsRNA -2). vsRNA duplex 1, but not duplex 2 reduced PTPRE expression compared to mock transfected cells (Figure 3C). Thus, YFV infection and RNA expression regulated PTPRE in Jurkat cells and regulated GFP via adding the PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR target sequence. Furthermore, transfection of synthetic YFV RNA representing this genome area was sufficient to regulate PTPRE following transfection of HEK cells. Thus, YFV and HCV independently evolved to inhibit PTPRE expression using an RNA-based mechanism [1].

To determine if the YFV-derived vsRNA sequences were present in YFV-infected Jurkat cells, next-generation RNA sequencing was performed using short (<200 nt) RNAs enriched from total cellular RNA obtained 4 days post–YFV infection [12]. In addition, short RNAs from Jurkat cells stably expressing the YFV envelope RNA were sequenced. YFV-specific vsRNAs containing the Y274 coding region were detected in infected Jurkat cells (Figure 3C) and Jurkat cells expressing YFV env RNA (Figure 3D). The size of the vsRNA sequences detected differed in the 2 cell types: a 39 nucleotide vsRNA present in YFV-infected cells and a 48-nt vsRNA in Jurkat cells expressing YFV env RNA. Both vsRNAs contained the PTPRE targeting sequence.

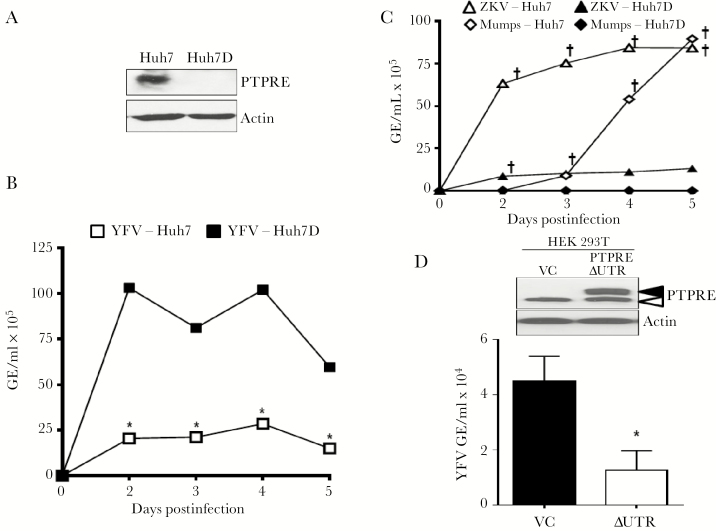

PTPRE Restricts YFV Replication In Vitro

Huh7 cells do not support HCV replication as well as the clonally derived Huh7D cells [31]. PTPRE expression was higher in Huh7 cells compared with Huh7D cells (Figure 4A). Like HCV, YFV replicated significantly better in Huh7D cells (Figure 4B), while ZKV and mumps replicated better in the parental Huh7 cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that PTPRE may restrict YFV replication and promote mumps and ZKV virus replication. To assess this further, HEK293T cells were transfected with a recombinant PTPRE expression plasmid in which the PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR was replaced with the bovine growth hormone 3ʹ-UTR lacking the YFV RNA “target” sequence (PTPREΔUTR). Endogenous cytoplasmic PTPRE variant 2 was detected in HEK293T cells transfected with either PTPREΔUTR or an empty vector control plasmid (VC); however, the transmembrane variant 1 was only observed in HEK 293T cells transfected with PTPRE ∆UTR (Figure 4D). YFV replication was reduced 5 days postinfection in HEK 239T cells expressing PTPRE ∆UTR compared to the VC (Figure 4D), demonstrating an inverse relationship between YFV replication and PTPRE expression, providing further evidence that YFV-mediated inhibition of PTPRE promotes viral replication in addition to reducing T-cell function.

Figure 4.

Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon (PTPRE) levels correlate with reduced yellow fever virus (YFV) and increased Zika and mumps virus replication. Huh7 cells express significantly more PTPRE than Huh7D cells (A), and YFV replication was significantly higher in Huh7D cells (B), whereas Zika virus (ZKV) and mumps virus replicated better in Huh7 cells (C). PTPRE expression in HEK 293T cells transfected with PTPRE variant 1 lacking the native 3ʹ-UTR (YFV ΔUTR) compared to the vector control (VC), and YFV replication in the VC and YFV ΔUTR transfected cells (D). Data represent 3 independent infections, and cell viability was equivalent between the different cell types on each day postinfection. P < .01 analysis of variance, Huh7 vs Huh7D for each virus. *P < .01 by t test at each day postinfection compared to Huh7 cells. †P < .01 greater viral replication compared to Huh7D cells. Abbreviations: GE, genomic equivalent; PTPRE, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon; VC, vector control; ZKV, Zika virus.

YFV Infection Reduces TCR Signaling and PTPRE Expression In Vivo

YFV and mumps infection of CD3+ enriched, murine lymphocytes obtained from C57BL/6N mice splenocytes demonstrated replication by both viruses (supplementary figure 7). As with human PBMCs, there was no difference in cell viability between YFV- and mumps-infected cells (not shown).

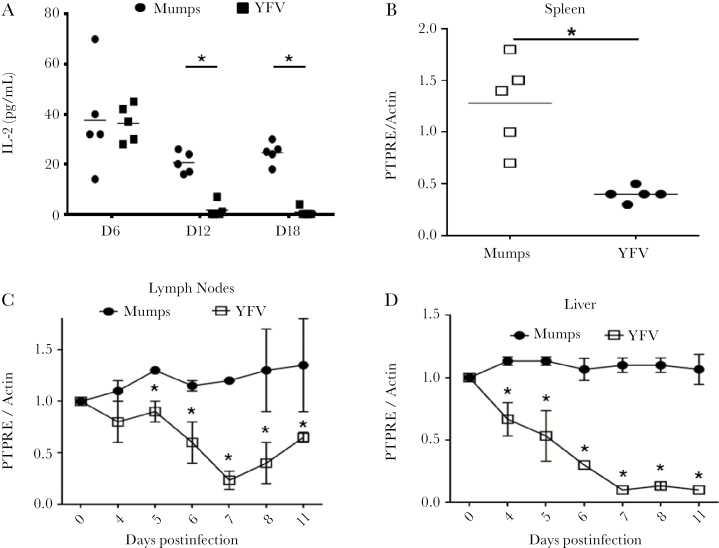

Sequence analysis determined that the human PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR YFV “seed” sequences are conserved in murine PTPRE. To determine if YFV infection regulated PTPRE expression in vivo, C57BL/6N mice were infected IP with YFV or mumps virus (2 × 106 TCID50 for each) using virus preparations generated in Vero cells. Mice were sacrificed on days 6, 12, and 18, and equal numbers of viable splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. IL-2 release was lower in mice inoculated with YFV on days 12 and 18 compared with mumps-infected mice (Figure 5A). Splenocyte, draining LNs, and liver PTPRE expression was also lower in YFV-inoculated mice compared to mice inoculated with mumps virus 7 days postinfection (Figure 5B–D and supplementary figure 8).

Figure 5.

Yellow fever virus (YFV), but not mumps virus, infection reduces T-cell receptor signaling in murine splenocytes and reduces protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon (PTPRE) protein expression in splenocytes, draining lymph nodes, and liver tissues. Mice (C57BL/6; n = 5 per group) were infected with 1 × 106 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) YFV or mumps virus intraperitoneally (IP), and sacrificed on the indicated days. Splenocytes were stimulated with anti-CD3 and interleukin 2 (IL-2) release measured (A). IL-2 measurements represent the average of 3 technical replicates and each experiment was independently repeated with consistent results. PTPRE levels relative to actin were measured in splenocytes 7 days postinfection (B), draining lymph nodes (C), and liver tissues (D) by immune blot analyses. *P < .01. Abbreviations: IL-2, interleukin 2; PTPRE, protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor epsilon; YFV, yellow fever virus.

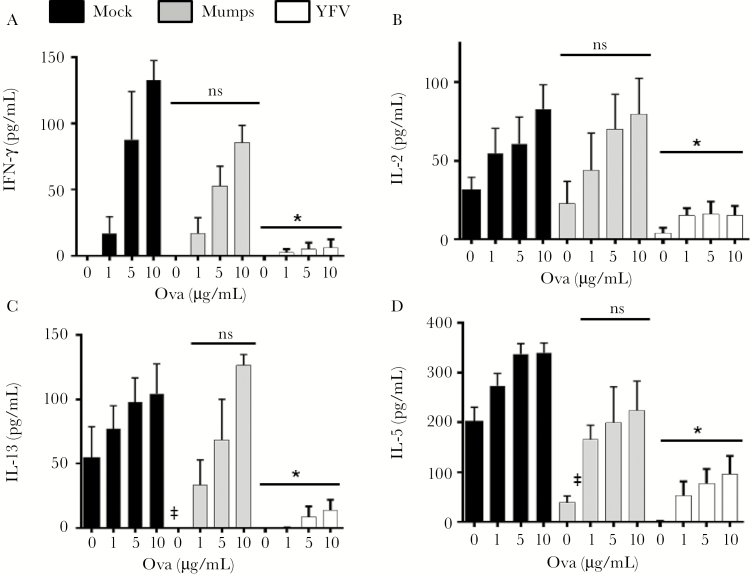

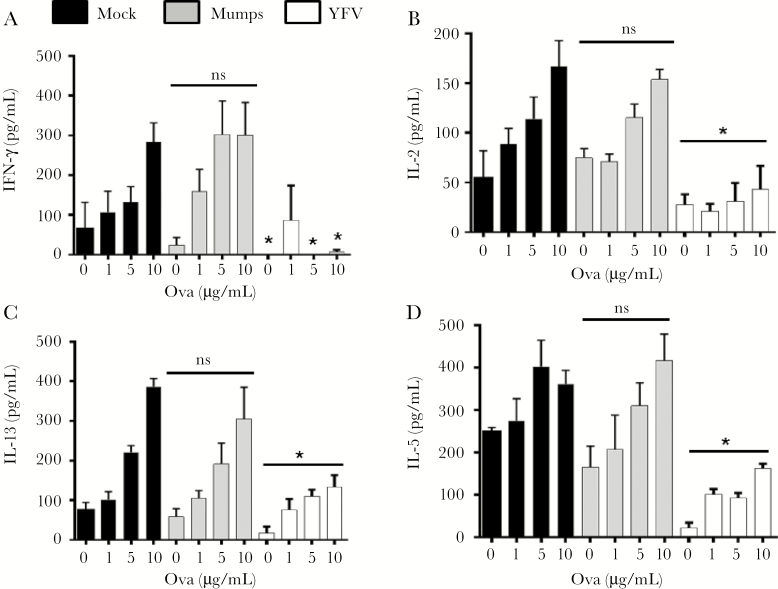

YFV vaccination is associated with reduced responsiveness to other vaccines [13, 14]. We examined the effect of YFV infection on immune responses to experimental vaccination. Mice infected with YFV, mumps virus, or uninfected controls (day 0) were inoculated IP with chicken ovalbumin in alum 7 and 14 days after YFV inoculation. On day 21, LN cells and splenocytes were restimulated with ovalbumin for 72 hours and ova-specific T-cell responses assessed by measuring IL-2, IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-13 in culture supernatant fluids. YFV-infected mice had a global reduction in LN and splenocyte cytokine levels compared to uninfected and mumps-infected mice (Figures 6 and 7). Taken together, these data suggest that YFV RNA regulates PTPRE expression, resulting in a reduction in T-cell receptor–mediated immune responses in vivo.

Figure 6.

Yellow fever virus (YFV) infection reduces ovalbumin (ova)–specific T-cell cytokines in lymph nodes following ova immunization in vivo. Mice (C57BL/6; n = 5 per group) were either mock-infected, or infected with 1 × 106 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) YFV or mumps virus intraperitoneally (IP) and sacrificed on the indicated days. Subsequently these mice were immunized IP with ova in alum 7 and 14 days after YFV or mumps virus infection (n = 5 per group). Animals were killed and lymph node cells prepared and stimulated with ova at the concentrations shown. The concentrations of interferon-γ, interleukin (IL) 2, IL-5, and IL-13 released into culture supernatants were measured 3 days later (A–D). *P < .01 compared to mumps- or mock-infected animals. Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; ns, not significant; YFV, yellow fever virus.

Figure 7.

Yellow fever virus (YFV) infection reduces ovalbumin (ova)–specific T-cell cytokines in splenocytes following ova immunization in vivo. Mice (C57BL/6; n = 5 per group) were either mock-infected, or infected with 1 × 106 median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) YFV or mumps virus intraperitoneally (IP) and sacrificed on the indicated days. Subsequently, these mice were immunized IP with ova in alum 7 and 14 days post-YFV or mumps virus infection (n = 5 per group). Animals were killed and splenocytes prepared and stimulated with ova at the concentrations shown. The concentrations of interferon-γ, interleukin (IL) 2, IL-5, and IL-13 released into culture supernatants were measured 3 days later (A–D). *P < .01 compared to mumps- or mock-infected animals. Abbreviations: IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; ns, not significant; YFV, yellow fever virus.

DISCUSSION

Expression of HCV and HPgV E2 protein reduces, but does not ameliorate, T-cell activation through the TCR [1, 9–11]. HCV and HPgV frequently cause persistent infection, and HPgV- and HCV-infected people have a demonstrable reduction in T-cell activation and ex vivo TCR signaling [1, 11, 17, 32]. We examined 3 flaviviruses that cause self-limited human infections to see if TCR signaling effects are conserved among the Flavivirus genus. ZKV and DENV-2 env expression did not reduce TCR signaling, nor did ZKV replication in Jurkat cells or primary human PBMCs. In contrast, YFV replication and expression of env coding RNA reduced TCR-mediated T-cell function. YFV is related to ZKV and DENV-2 more closely than HCV by phylogeny, transmission, and disease, so it is surprising that YFV and HCV share a TCR inhibition mechanism. Because PTPRE appears to restrict YFV and HCV replication, we speculate that these viruses evolved mechanisms to reduce PTPRE expression to allow amplification of replication. Since PTPRE enhanced ZKV and mumps virus replication, reducing PTPRE would be detrimental for these viruses.

The YFV-17D vaccine is one of the oldest and most effective human vaccines, and it elicits a broad repertoire of specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses [33]. At first glance, TCR inhibition may not seem biologically plausible. However, 2 features of YFV infection may contribute to our findings. First, YFV replication occurs in many cell types including epithelial cells, dendritic cells (DCs), T cells and B cells, and local virus replication disseminates by viremia [34, 35]. Thus, viral antigens are presented to T cells at multiple locations during infection, and YFV activates DCs [34]. Second, YFV regulated, but did not abolish, TCR signaling. Our data show that YFV infection modulates TCR signaling and PTPRE expression in mice, reducing T-cell cytokine production including IL-2, resulting in a blunting of immunological signals to numerous cell types in both the innate and adaptive immune systems [36]. As a result, YFV-mediated inhibition of TCR signaling may facilitate the establishment of infection and contribute to immune evasion by slowing the activation of the adaptive immune response.

Our study identified several novel features regarding YFV infection effects on T-cell function. First, YFV infection of primary T cells and transformed T-cell lines reduced TCR-mediated activation, and TCR stimulation prior to infection reduced YFV replication. Second, YFV infection of human and murine primary T cells and a transformed human T-cell line reduced expression of PTPRE, a Src kinase–activating phosphatase. This sequence targeted 2 sites on the PTPRE 3ʹ-UTR. Substitution of 2 residues in the YFV targeting sequence restored PTPRE expression and T-cell function. Third, transfection of a synthetic YFV vsRNA duplex reduced PTPRE expression in vitro. Fourth, PTPRE expression correlated with YFV replication, and expression of PTPRE lacking the 3ʹ-UTR reduced YFV replication in vitro. Thus, it appears that PTPRE may be a novel YFV restriction factor. Finally, PTPRE expression in liver, draining LN, and splenic mononuclear cells was reduced in YFV-infected mice, and this correlated with impaired TCR signaling and reduced responses to immunization with ovalbumin. Taken together, these data suggest that YFV RNA targets PTPRE, a novel restriction factor expressed by numerous cell types including T cells, to promote viral replication and impair host T-cell function.

The finding that YFV reduced T-cell function is consistent with clinical studies showing that coadministration of YFV vaccine results in a reduction in immune response to the other vaccine [13, 14]. Furthermore, the reduction in YFV replication following T-cell activation may explain why YFV vaccine efficacy is reduced in recipients with activated immune profiles compared to those without [37]. This effect is shared with HCV, but not 2 other viruses in the Flavivirus genus (ZKV, DENV). The finding that PTPRE inhibited YFV but not ZKV replication may explain why YFV evolved to target this Lck-regulating phosphatase.

Although DNA viruses and retroviruses encode small RNAs that influence viral replication and host immune responses [38, 39], there is controversy regarding the ability of strictly cytoplasmic RNA viruses to generate functional vsRNAs [40, 41]. Studies by Andrew Fire’s group and others identified vsRNAs in cells infected with several cytoplasmic RNA viruses [1, 12, 42–47]. Many of these vsRNAs have characteristics distinguishing them from RNAs generated by nonspecific degradation of full-length viral RNA [12]. A previous study concluded that vsRNAs do not influence YFV replication as replication was the same in 293T cells with or without Dicer 36 hours postinfection [41]. However, we found that 72 hours of YFV infection was required to reduce cellular PTPRE levels by 50% (Figure 4) [41]. Furthermore, Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis may occur [48, 49]. We identify a previously unrecognized role of vsRNAs during RNA virus replication, and YFV vsRNA may represent a novel posttranscriptional mechanism of host cell gene regulation that promotes viral replication while blunting T-cell immune responses.

Many DNA and RNA viruses interfere with TCR signaling [1, 3, 10]. For viruses that primarily grow in T lymphocytes, this likely maintains the balance between inducing activation required for viral growth (ie, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), and dampening levels of activation that lead to activation-induced-T-cell death. In contrast, reducing TCR signaling by viruses that replicate primarily in other cell types (eg, HCV and YFV) may provide a previously unrecognized mechanism of T-cell immune evasion. A previous study found that PTPRE facilitates HIV replication [50], and both ZKV and mumps virus infections were reduced in the Huh7D cells with low PTPRE levels (Figure 4). Thus, PTPRE may serve as either a restriction factor (YFV) or proviral factor (HIV, possibly ZKV and mumps). Future studies into the role of PTPRE in the viral replication cycle may identify novel targets for therapeutics.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank our healthy blood donors for their participation in these studies; Dr Charles Rice (Rockefeller University) for the YFV infectious clone; Drs Catherine Miller-Hunt (University of Western Illinois) and Wendy Maury (University of Iowa) for the ZKV PR strain virus; Dr Dino Feigelstock (Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration [FDA/CBER]) for Huh7D cells; Dr Lewis Markoff (FDA/CBER) for the DENV-2 env coding plasmid; and Dr Ceren Ciraci and Ms Vickie Knepper-Adrian for their technical assistance. We also thank Justin Fishbaugh of the University of Iowa Flow Cytometry Facility, and Einat Snir and Jennifer Bair of the University of Iowa DNA core research facility for their technical assistance.

Financial support. This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (merit review grants BX001241 to J. X. and BX000207 to J. T. S.). Work performed at the University of Iowa Flow Cytometry Facility and DNA core research facility (University of Iowa Genomics Division, Iowa Institute of Human Genetics) were both supported by the Carver College of Medicine/Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center, which is supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award number P30CA086862), and from a pilot grant from the University of the Vice President for Research, University of Iowa (to J. T. S.).

Potential conflicts of interest. J. X., J. T. S., N. B., and J. H. M. have a patent application related to the use of YFV envelope RNA or protein for therapeutic purposes. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: 23rd International Symposium on Hepatitis C Virus and Related Viruses (HCV2016), Kyoto, Japan, 11–15 October 2016. Poster P-17.

References

- 1. Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J, Kaufman TM, Stapleton JT. Conserved motifs within hepatitis C virus envelope (E2) RNA and protein independently inhibit T cell activation. PLoS Pathog 2015; 11:e1005183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medzhitov R, Janeway CA Jr. Innate immune recognition and control of adaptive immune responses. Semin Immunol 1998; 10:351–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jerome KR. Viral modulation of T-cell receptor signaling. J Virol 2008; 82:4194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol 2017; 98:2–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kraemer MU, Faria NR, Reiner RC Jr et al. Spread of yellow fever virus outbreak in Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo 2015–16: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:330–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jorge TR, Mosimann AL, Noronha L, Maron A, Duarte Dos Santos CN. Isolation and characterization of a Brazilian strain of yellow fever virus from an epizootic outbreak in 2009. Acta Trop 2017; 166:114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paules CI, Fauci AS. Yellow fever—once again on the radar screen in the Americas. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:1397–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paules CI, Fauci AS. Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: the dichotomy between acute outbreaks and chronic endemicity. JAMA 2017; 317:691–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J, Kaufman TM, Stapleton JT. GB virus C envelope protein E2 inhibits TCR-induced IL-2 production and alters IL-2-signaling pathways. J Immunol 2012; 189:2211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J, Landay AL, Chivero ET, Stapleton JT. GB virus C particles inhibit T cell activation via envelope E2 protein-mediated inhibition of TCR signaling. J Immunol 2013; 190:6351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhattarai N, McLinden JH, Xiang J et al. Hepatitis C virus infection inhibits a Src-kinase regulatory phosphatase and reduces T cell activation in vivo. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13:e1006232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parameswaran P, Sklan E, Wilkins C et al. Six RNA viruses and forty-one hosts: viral small RNAs and modulation of small RNA repertoires in vertebrate and invertebrate systems. PLoS Pathog 2010; 6:e1000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nascimento Silva JR, Camacho LA, Siqueira MM et al. ; Collaborative Group for the Study of Yellow Fever Vaccines Mutual interference on the immune response to yellow fever vaccine and a combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella. Vaccine 2011; 29:6327–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nasveld PE, Marjason J, Bennett S et al. Concomitant or sequential administration of live attenuated Japanese encephalitis chimeric virus vaccine and yellow fever 17D vaccine: randomized double-blind phase II evaluation of safety and immunogenicity. Hum Vaccin 2010; 6:906–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wünschmann S, Medh JD, Klinzmann D, Schmidt WN, Stapleton JT. Characterization of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HCV E2 interactions with CD81 and the low-density lipoprotein receptor. J Virol 2000; 74:10055–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xiang J, McLinden JH, Rydze RA et al. Viruses within the Flaviviridae decrease CD4 expression and inhibit HIV replication in human CD4+ cells. J Immunol 2009; 183:7860–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stapleton JT, Chaloner K, Martenson JA et al. GB virus C infection is associated with altered lymphocyte subset distribution and reduced T cell activation and proliferation in HIV-infected individuals. PLoS One 2012; 7:e50563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ciraci C, Janczy JR, Jain N et al. Immune complexes indirectly suppress the generation of Th17 responses in vivo. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0151252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Janczy JR, Ciraci C, Haasken S et al. Immune complexes inhibit IL-1 secretion and inflammasome activation. J Immunol 2014; 193:5190–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mohr EL, Xiang J, McLinden JH et al. GB virus type C envelope protein E2 elicits antibodies that react with a cellular antigen on HIV-1 particles and neutralize diverse HIV-1 isolates. J Immunol 2010; 185:4496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:1232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bredenbeek PJ, Kooi EA, Lindenbach B, Huijkman N, Rice CM, Spaan WJ. A stable full-length yellow fever virus cDNA clone and the role of conserved RNA elements in flavivirus replication. J Gen Virol 2003; 84:1261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiang J, McLinden JH, Chang Q, Kaufman TM, Stapleton JT. An 85-aa segment of the GB virus type C NS5A phosphoprotein inhibits HIV-1 replication in CD4+ Jurkat T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:15570–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xiang J, McLinden JH, Kaufman TM et al. Characterization of a peptide domain within the GB virus C envelope glycoprotein (E2) that inhibits HIV replication. Virology 2012; 430:53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J et al. Zika virus infection during pregnancy in mice causes placental damage and fetal demise. Cell 2016; 165:1081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davis SJ, van der Merwe PA. Lck and the nature of the T cell receptor trigger. Trends Immunol 2011; 32:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Xue Y, Liu Z, Cao J et al. GPS 2.1: enhanced prediction of kinase-specific phosphorylation sites with an algorithm of motif length selection. Protein Eng Des Sel 2011; 24:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahmed F, Kaundal R, Raghava GP. PHDcleav: a SVM based method for predicting human Dicer cleavage sites using sequence and secondary structure of miRNA precursors. BMC Bioinformatics 2013; 14(Suppl 14):S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levy-Apter E, Finkelshtein E, Vemulapalli V, Li SS, Bedford MT, Elson A. Adaptor protein GRB2 promotes Src tyrosine kinase activation and podosomal organization by protein-tyrosine phosphatase ϵ in osteoclasts. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:36048–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jang IK, Zhang J, Chiang YJ et al. Grb2 functions at the top of the T-cell antigen receptor-induced tyrosine kinase cascade to control thymic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:10620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Feigelstock DA, Mihalik KB, Kaplan G, Feinstone SM. Increased susceptibility of Huh7 cells to HCV replication does not require mutations in RIG-I. Virol J 2010; 7:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stapleton JT, Chaloner K, Zhang J et al. GBV-C viremia is associated with reduced CD4 expansion in HIV-infected people receiving HAART and interleukin-2 therapy. AIDS 2009; 23:605–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. James EA, LaFond RE, Gates TJ, Mai DT, Malhotra U, Kwok WW. Yellow fever vaccination elicits broad functional CD4+ T cell responses that recognize structural and nonstructural proteins. J Virol 2013; 87:12794–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Palmer DR, Fernandez S, Bisbing J et al. Restricted replication and lysosomal trafficking of yellow fever 17D vaccine virus in human dendritic cells. J Gen Virol 2007; 88:148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Douam F, Hrebikova G, Albrecht YE et al. Single-cell tracking of flavivirus RNA uncovers species-specific interactions with the immune system dictating disease outcome. Nat Commun 2017; 8:14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Xiao P, Tuero I, Patterson LJ, Robert-Guroff M. NK and CD4+ T cell cooperative immune responses correlate with control of disease in a macaque simian immunodeficiency virus infection model. J Immunol 2012; 189:1878–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Muyanja E, Ssemaganda A, Ngauv P et al. Immune activation alters cellular and humoral responses to yellow fever 17D vaccine. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:3147–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harwig A, Das AT, Berkhout B. Retroviral microRNAs. Curr Opin Virol 2014; 7:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kincaid RP, Sullivan CS. Virus-encoded microRNAs: an overview and a look to the future. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8:e1003018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cullen BR. Viruses and RNA interference: issues and controversies. J Virol 2014; 88:12934–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bogerd HP, Skalsky RL, Kennedy EM et al. Replication of many human viruses is refractory to inhibition by endogenous cellular microRNAs. J Virol 2014; 88:8065–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi J, Duan Z, Sun J et al. Identification and validation of a novel microRNA-like molecule derived from a cytoplasmic RNA virus antigenome by bioinformatics and experimental approaches. Virol J 2014; 11:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hussain M, Asgari S. MicroRNA-like viral small RNA from dengue virus 2 autoregulates its replication in mosquito cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:2746–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rouha H, Thurner C, Mandl CW. Functional microRNA generated from a cytoplasmic RNA virus. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38:8328–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shi J, Sun J, Wang B et al. Novel microRNA-like viral small regulatory RNAs arising during human hepatitis A virus infection. FASEB J 2014; 28:4381–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perez JT, Varble A, Sachidanandam R et al. Influenza A virus-generated small RNAs regulate the switch from transcription to replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:11525–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Y, Basavappa M, Lu J et al. Induction and suppression of antiviral RNA interference by influenza A virus in mammalian cells. Nat Microbiol 2016; 2:16250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shapiro JS, Langlois RA, Pham AM, Tenoever BR. Evidence for a cytoplasmic microprocessor of pri-miRNAs. RNA 2012; 18:1338–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shapiro JS, Varble A, Pham AM, Tenoever BR. Noncanonical cytoplasmic processing of viral microRNAs. RNA 2010; 16:2068–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rato S, Maia S, Brito PM et al. Novel HIV-1 knockdown targets identified by an enriched kinases/phosphatases shRNA library using a long-term iterative screen in Jurkat T-cells. PLoS One 2010; 5:e9276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.