Abstract

Mycoplasma genitalium is one of the major causes of nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) worldwide but an uncommon sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the general population. The risk of sexual transmission is probably lower than for Chlamydia trachomatis. Infection in men is usually asymptomatic and it is likely that most men resolve infection without developing disease. The incubation period for NGU caused by Mycoplasma genitalium is probably longer than for NGU caused by C. trachomatis. The clinical characteristics of symptomatic NGU have not been shown to identify the pathogen specific etiology. Effective treatment of men and their sexual partner(s) is complicated as macrolide antimicrobial resistance is now common in many countries, conceivably due to the widespread use of azithromycin 1 g to treat STIs and the limited availability of diagnostic tests for M. genitalium. Improved outcomes in men with NGU and better antimicrobial stewardship are likely to arise from the introduction of diagnostic M. genitalium nucleic acid amplification testing including antimicrobial resistance testing in men with symptoms of NGU as well as in their current sexual partner(s). The cost effectiveness of these approaches needs further evaluation. The evidence that M. genitalium causes epididymo-orchitis, proctitis, and reactive arthritis and facilitates human immunodeficiency virus transmission in men is weak, although biologically plausible. In the absence of randomized controlled trials demonstrating cost effectiveness, screening of asymptomatic men cannot be recommended.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, men, nongonococcal urethritis, nucleic acid amplification test, antimicrobial resistance

Mycoplasma genitalium is a sexually transmitted microorganism that has the potential to cause clinical disease, in men more so than women. Although it was first identified in men with nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) in 1980, much remains unclear about the natural history of untreated infection. While there is clear association with NGU in men, the clinical evidence that it causes epididymo-orchitis, proctitis, reactive arthritis and facilitates human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission in men is weak, although biologically plausible. It is not known how long asymptomatic infection persists in untreated men, nor the risk of developing disease if left untreated. Although there is evidence of sexual transmission from male to female, it is unclear how often this occurs and of the risk of developing reproductive tract disease.

With the advent of commercially available tests in some countries but not the United States, M. genitalium diagnosis is now possible in some settings. However, the cost effectiveness of screening and diagnostic testing using M. genitalium nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) has not been evaluated in randomized trials. Undertaking and interpreting such clinical studies will be complex as macrolide antimicrobial resistance is now common in many countries, most likely due to the widespread use of azithromycin 1 g to treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and fluoroquinolone resistance is beginning to emerge [1–4]. This emphasizes the importance of adopting the principles of good antimicrobial stewardship, including the use of accurate diagnostics (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15/chapter/1-Recommendations#terms-used-in-this-guideline) and undertaking a test of cure, when considering how best to manage this infection in clinical practice.[2]

In this review article, we examine the evidence available on the epidemiology, clinical presentation, and natural history in men, and also examine the potential benefits of utilizing M. genitalium NAAT testing in a diagnostic setting with and without antimicrobial resistance testing, not only in managing the patient but its potential role in informing partner notification and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

There are 2 large population-based survey studies of M. genitalium available that have provided us with unbiased information on the epidemiology of this emerging sexually transmitted pathogen in asymptomatic men [5, 6]. The first of these was based on Wave III of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health in the United States [6]. Young adults between the ages of 18 and 27 years were enrolled between 2001 and 2002. Mycoplasma genitalium prevalence in men was 1.1% and 0.8% in women, with an overall prevalence of 1.0%. In contrast, the prevalences of chlamydial, gonococcal, and trichomonal infections were 4.2%, 0.4%, and 2.3% respectively. After adjustment for other risk factors, M. genitalium infection was strongly associated with increasing numbers of sexual partners and black race. The second study was a probability sample survey in Britain, the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL-3), conducted between 2010 and 2012 among sexually experienced men and women between the ages of 16 and 44 [5]. In this study, the prevalence of M. genitalium in men was 1.2% and in 1.3% in women. Risk factors for M. genitalium infection included black race, increased numbers of total and new sex partners, and unsafe sexual practices. A smaller population-based survey of young men aged 21–24 years from Aarhus County, Denmark in 1997–1998 observed a similar prevalence of 1.1% and an association with increasing number of sexual partners [7].

Among males, the most common clinical manifestation of M. genitalium infection is NGU. It is currently unknown what proportion of men infected with M. genitalium develop NGU, but it is probably only a minority. If we assume a duration of infection of 1 year, we can estimate using data from England in 2011 that approximately 6500 of 125000 (5.2%) M. genitalium–positive men developed NGU [8–12]. In this supplement, McGowin and Totten review mechanisms of persistence and immune evasion by M. genitalium that enable it to establish chronic and persistent infection [13]. Women can resolve infection spontaneously and it is likely men can as well. The duration of infection in women varies from a few months to over a year; however, we do not know the duration of infection in men [14–17].

The proportion of cases caused by M. genitalium varies geographically and by socioeconomic status. Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the most common cause of urethritis in most developing regions of the world [18]. Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common pathogen associated with NGU followed by M. genitalium and, in the United States, Trichomonas vaginalis [19–21]. Mycoplasma genitalium can also cause infection in men with gonococcal urethritis, although C. trachomatis is more common [18, 22]. Mycoplasma genitalium is now recognized as the dominant organism associated with persistent NGU following treatment of NGU [19].

Survey studies of men who have sex with men (MSM) reveal higher rates of all STIs than observed in population-based surveys. In a survey of MSM attending saunas in Australia, Bradshaw et al [23] found the prevalence of M. genitalium to be 2.1% compared to prevalence rates of 8.1% for C. trachomatis and 4.8% for N. gonorrhoeae. Importantly, all organisms were significantly more common in the rectum than in either the urethra or the pharynx. These findings have been replicated in several other studies of different MSM populations [24–26]. Of interest, C. trachomatis and M. genitalium prevalence rates are lower among MSM with NGU than in heterosexual men, with a higher proportion of NGU cases being idiopathic in MSM [27, 28]. Soni et al [24] found that M. genitalium was more prevalent in men with HIV infection whereas the prevalence of C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae was not influenced by HIV status. If supported, this finding may provide clues to key differences in the host immune response to these organisms.

In summary, M. genitalium is one of the major causes of NGU worldwide but an uncommon STI in the general population. Infection in men is usually asymptomatic and it is likely that most men resolve infection without developing disease.

IMMUNOPATHOGENESIS: NGU AND PROCTITIS

Mycoplasma genitalium is a slow-growing microorganism that can replicate both intracellularly and extracellularly and is able to establish chronic infections [29]. During chronic epithelial cell infection, it produces proinflammatory cytokines that predominantly consist of potent chemotactic and/or activating factors for phagocytes [30]. This is discussed in more detail by McGowin and Totten in this supplement [13].

SEXUAL TRANSMISSION

Although it is now well established that M. genitalium is sexually transmitted, it is not known how often this occurs per episode of unprotected sexual intercourse [29]. Estimates for chlamydial transmission from men to women per episode of vaginal coitus have been based on observational studies and range from 10% to 39.5% with the lower estimate based on a recent transmission dynamic mathematical model using the dyad study of Quinn et al [31–33]. Studies of sexual dyads suggest that transmission is probably lower than that for C. trachomatis, which would be consistent with lower infectious load of M. genitalium compared to C. trachomatis [33–35]. It is likely that men with symptomatic NGU and presumably higher M. genitalium loads may be more infectious than men with asymptomatic infection [34, 36–38]. Studies of both C. trachomatis and M. genitalium in older men also provide additional insights into the relative transmission dynamics of these commonly associated STIs. Napierala et al [39] tested for M. genitalium in 2750 preserved specimens originally submitted to a reference laboratory for C. trachomatis testing from STI and community clinics including men ranging in age from adolescents to those >60 years of age. As has been shown in numerous STI clinic–based studies, the highest prevalence of C. trachomatis infection was in those aged <20 years with a progressive prevalence decrease to very low levels among individuals >40 years of age. In contrast, the age group with the highest prevalence of M. genitalium was in 20- to 30-year-olds. Though M. genitalium prevalence rates decreased in the over-30 age groups, the decline was not as steep as was observed for C. trachomatis and, strikingly, among men >40 years of age, M. genitalium was more common than C. trachomatis. These findings were corroborated by the NATSAL-3 population-based survey [5, 40]. Taken together, these observations suggest the hypothesis that the average duration of M. genitalium infection in men is longer than the average duration of C. trachomatis infection while the lower prevalence of M. genitalium infection in younger males compared to C. trachomatis provides further support for the hypothesis that infectivity of M. genitalium is lower than that of C. trachomatis.

As carriage of M. genitalium in the oropharynx appears to be very uncommon, transmission through oral sex is likely to be rare [41, 42]. It is unknown whether risk of transmission differs between anal and vaginal intercourse.

MYCOPLASMA GENITALIUM AND NGU

Given that M. genitalium was first identified in men with NGU and that it induces the release of proinflammatory cytokines, it is not surprising that M. genitalium has been strongly and consistently associated with NGU [29, 30]. Taylor-Robinson and Jensen in 2011 reviewed all the published literature and observed that M. genitalium has been detected in 15%–25% of men with symptomatic NGU, compared to about 5%–10% of those without disease (odds ratio [OR], 5.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 4.3–7.0) [29]. In several studies, the clinical characteristics of symptomatic NGU have not been shown to identify the pathogen-specific etiology [20, 21, 43].

Incubation Period of NGU

The recommended period for contact tracing in men presenting with NGU ranges from 4 weeks to 60 days from the onset of symptoms [19, 44]. For the European guideline, this is based on the assumption that the incubation period for chlamydial NGU is 2–4 weeks. Although the incubation period for the development of M. genitalium NGU is unknown, it is likely that M. genitalium’s slow replication rate compared to chlamydia would result in a more prolonged incubation period before NGU develops [29]. Thus, while the limited evidence available suggests this could be up to 60 days, it may be potentially even longer [30]. Comparison of infectious disease epidemiology in men with chlamydia and M. genitalium in NGU studies may provide insights as to whether this is the case. However, there are a number of biases that make these data difficult to interpret, including high-risk behavior of controls and attendance as a result of being a contact of an STI [9, 20]. Nevertheless, in the case-control study by Leung et al, men with M. genitalium NGU were no more likely to have had a new partner or >1 partner compared to controls whereas chlamydial NGU was associated with these behavioral risk factors [9]. Wetmore et al observed that the mean duration of relationship for the most recent partner for men with NGU was longer for M. genitalium–positive men (days) than for chlamydia-positive men (mean, 75 vs 16 days, respectively) [21]. These data provide additional support for the hypothesis that the infectivity of M. genitalium is less than that of C. trachomatis.

Definition of NGU and Initiating Treatment

There are 2 working definitions of NGU used in clinical practice [19, 44]. While both include the presence of urethral discharge, dysuria, and/or urethral irritation and the requirement for objective evidence of urethral inflammation, the European guideline uses ≥5 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNLs) per high-power field (hpf) (×1000) on a stained urethral smear and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guideline uses ≥2 PMNLs/hpf [19, 44]. Treatment using a lower cutoff may result in overtreatment of many men with low-grade urethritis (2–4 PMNLs/hpf) who do not have an infection (see below). In Europe it is recommended that symptomatic men with <5 PMNLs/hpf are reassured and asked to return for an early-morning smear if their symptoms do not settle and their NAAT tests for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae are negative [19]. This is because some men with low-grade urethritis will have been misclassified because of the inaccuracy of the urethral smear [8]. There is currently no evidence of significant morbidity in symptomatic chlamydia and gonorrhea NAAT-negative men with <5 PMNLs/hpf on a urethral smear who are reassured and do not receive antimicrobial therapy. Many of these men get better without treatment [19].

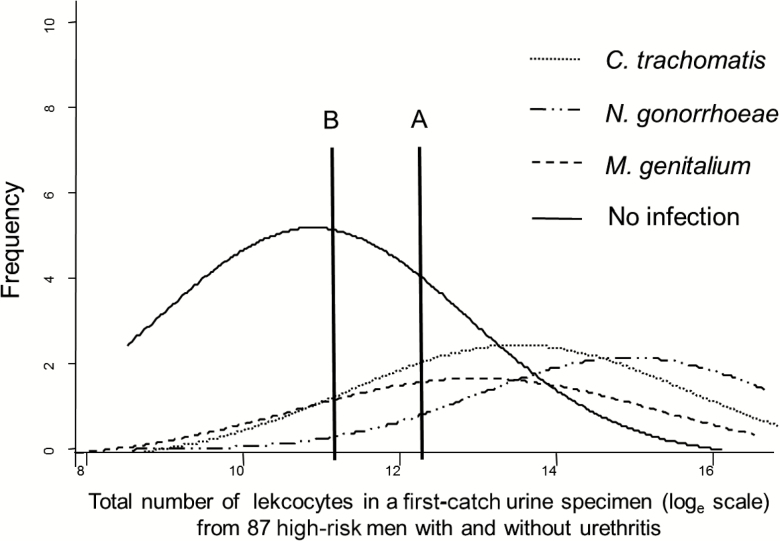

While reducing the PMNL count cutoff will increase the number of men identified and treated for presumptive chlamydia or M. genitalium infection, it will also disproportionately increase the number of men (and their partner[s]) without a sexually transmitted infection, diagnosed and treated for NGU. Figure 1 is a theoretical representation of the distribution of urinary leukocytes (ULs) of high-risk men infected with M. genitalium. This representation is based on the findings of Wiggins et al, who investigated the UL distribution in 87 high-risk men presenting to a genitourinary medicine department [45]. These men were tested for C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and urethritis but not M. genitalium. A previous study in the same population had demonstrated that M. genitalium prevalence was about half that of C. trachomatis, and the observations of Moi et al indicate that the inflammatory response is less marked [9, 46]. As the UL count and the PMNLs/hpf are correlated, changes in the UL count can be used to explore how changes in the urethral smear cutoff will affect detection of C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, and M. genitalium [45, 46]. When the UL threshold (Figure 1, threshold A), which approximated the urethral smear cutoff 5 PMNLs/hpf in the study, is lowered (Figure 1, threshold B), more high-risk men in the population tested for urethritis with M. genitalium, C. trachomatis, and N. gonorrhoeae will be identified. However, the specificity of urethritis for detecting men with these infections will also decrease and, as the cell count threshold is reduced, disproportionately more high-risk men (and their partners) with no infection compared to those with an infection will require treatment as a result of being diagnosed with NGU. This would also be expected to be the case with a urethral smear [45–47]. While other infections such as Ureaplasma urealyticum or Trichomonas vaginalis (in populations where this microorganism is prevalent) can account for some cases, the specific etiology in men not infected with STI pathogens is unclear [19]. This concept is also consistent with the observations that idiopathic NGU has a lower mean leukocyte count compared to men in whom an infection is detected [20, 21, 43].

Figure 1.

Hypothetical frequency distribution of urinary leukocyte counts for Mycoplasma genitalium and no infection in high-risk men presenting to a genitourinary medicine department who were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Line A correlates with the urethral smear cutoff of 5 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-power field for nongonococcal urethritis, and line B demonstrates the effect on sexually transmitted infection detection if the cutoff is decreased. Adapted from Wiggins et al [45].

In summary, reducing the PMNL count cutoff from ≥5 to ≥2 to for diagnosing NGU will increase the number of men identified and treated for presumptive chlamydia or M. genitalium infection but will also disproportionately increase the number of men (and their partner[s]) without a sexually transmitted infection, diagnosed, and treated for NGU.

NAAT Testing for M. genitalium in Men With Symptoms of NGU

Currently, NAAT testing is not available in many centers but is anticipated over the next few years. The European NGU guideline advises that M. genitalium NAAT testing, preferably with macrolide resistance testing in men with NGU, is likely to be cost effective, as this would enable the implementation of more effective treatment strategies. It is also likely that testing symptomatic men who do not meet the PMNL NGU diagnosis criteria for STI pathogens, including M. genitalium, and withholding treatment pending the results would reduce unnecessary antimicrobial therapy. Whether or not testing STI-pathogen NAAT negative, in this group of men, would reduce reattendance for an early-morning smear and/or the persistence of symptoms, as currently recommended in Europe, remains to be demonstrated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Exploring Potential Benefits Associated With Mycoplasma genitalium Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing With or Without Antimicrobial Resistance Testing in Men Presenting with Symptoms of Nongonococcal Urethritis Compared to Current Standards of Care

| No M. genitalium NAAT Testing Following European Guidelines | No M. genitalium NAAT Testing Following CDC Guidelines | M. genitalium NAAT Testing Plus Knowledge of Local AMR Prevalence | M. genitalium NAAT Testing Plus Macrolide AMR Testing and Knowledge of Local Quinolone AMR Prevalence | M. genitalium NAAT Testing Plus Macrolide and Quinolone AMR Testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms of NGU | Management | NAAT test for CT and NG and confirm patient has NGU based on ≥5 PMNLs/ hpf | NAAT test for CT and NG and confirm patient has NGU based on ≥2 PMNLs/hpf | Confirm man has NGU on microscopya | Confirm man has NGU on microscopya | Confirm man has NGU on microscopya |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | Unable to reassure if low- grade urethritis <5 PMNLs/ hpfb | More CT infected men are treated but disproportionately greater increase in treatment of men with no infection (Figure 1) | Able to reassure if low- grade urethritis <5 PMNLs/hpfc | Able to reassure if low- grade urethritis <5 PMNLs/hpfc | Able to reassure if low- grade urethritis <5 PMNLs/hpfc | |

| Confirmed NGU | Management | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d | Azithromycin 1 g or Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d (European guideline) | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d (European guideline) | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d (European guideline) |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Azithromycin 1 g associated with development of macrolide AMR in M. genitalium | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | |

| Contacts of NGU | Management | NAAT test for CT and NG then doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d | Azithromycin 1 g or Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d and test for M. genitaliuma | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d and test for M. genitaliuma | Doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d and test for M. genitaliuma |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Azithromycin 1 g associated with development of macrolide AMR in M. genitalium | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | Does not reduce antimicrobial therapeutic options if treatment is not effective | |

| Persistent/ recurrent NGU | Management | Azithromycin 5 d regimend plus metronidazole 400 mg bid 5 d | Moxifloxacin 400 mg of 7 d if treated with azithromycin 1 g initially; Azithromycin 1 g if initial treatment doxycycline 100 mg bid 7 d. Plus metronidazole/tinidazole 2 g if partner(s) female and Trichomonas vaginalis prevalent | Azithromycin 5 d regimend if M. genitalium negative. If M. genitalium positive, choice of azithromycin or moxifloxacin to be guided by local prevalence of macrolide and quinolone AMR. Plus metronidazolee | Azithromycin 5 d regimend if M. genitalium negative. If M. genitalium positive, choice of azithromycin or moxifloxacin to be guided by macrolide AMR result and knowledge of local prevalence of quinolone AMR. Plus metronidazolee | Azithromycin 5 d regimend if M. genitalium negative. If M. genitalium positive, choice of azithromycin or moxifloxacin to be guided by macrolide and quinolone AMR result. Plus metronidazolee |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | Likely to be effective unless macrolide-resistant M. genitalium etiology of NGU | Moxifloxacin effective against macrolide AMR M. genitalium. Azithromycin 1 g associated with development of macrolide AMR in M. genitalium | Improved cure rates following second-line therapy | Improved cure rates following second-line therapy | Improved cure rates following second-line therapy | |

| M. genitalium detected | Management | Test of cure: not possible | Test of cure: not possible | Test of cure ≥3 wk after start of treatment | Test of cure ≥3 wk after start of treatment | Test of cure ≥3 wk after start of treatment |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | Risk of spread of resistant strains that have developed following treatment | Risk of spread of resistant strains that have developed following treatment | Prevents spread of resistant strains that have developed following treatment but are asymptomatic | Prevents spread of resistant strains that have developed following treatment but are asymptomatic | Prevents spread of resistant strains that have developed following treatment but are asymptomatic | |

| Contacts of persistent/ recurrent NGU | Management | No further treatment | No further treatment | Treatment guided by NAAT results of tests prior to epidemiological treatment | Treatment guided by NAAT results of tests prior to epidemiological treatment | Treatment guided by NAAT results of tests prior to epidemiological treatment |

| Advantages/ disadvantages | At risk of reinfection if M. genitalium etiology of NGU | At risk of reinfection if M. genitalium etiology of NGU | Reduced risk of reinfection and inappropriate additional antimicrobial therapy | Reduced risk of reinfection and inappropriate additional antimicrobial therapy | Reduced risk of reinfection and inappropriate additional antimicrobial therapy | |

| Antimicrobial stewardship | Not good | Poor | Good | Very good | Very good |

Abbreviations: AMR, antimicrobial resistance; bid, twice daily; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CT, Chlamydia trachomatis; hpf, high-powered field; M. genitalium, Mycoplasma genitalium; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; NG, Neisseria gonorrhoeae; PMNL, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

aAssumes NAAT testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea, which would also include trichomonas depending on local population prevalence.

bMen are invited back for an early-morning smear after holding their urine overnight if symptoms do not settle and CT/NG NAAT negative.

cReassurance in these cases would be based on negative NAAT for M. genitalium, CT, and NG ± trichomonas.

dAzithromycin 500 mg immediately, then 250 mg for 4 days.

eIf trichomonas NAAT-positive. Metronidazole 400 mg bid 5 days currently recommended for treatment of possible bacterial vaginosis–associated bacteria in European guidelines [8], but benefit is unclear.

Retesting Men if M. genitalium NAAT Positive

The European guideline recommends that all persons testing M. genitalium NAAT-positive should be retested at the earliest 3 weeks after commencement of therapy due to the high prevalence of macrolide resistance either present pretreatment or developing during treatment with azithromycin [2]. Many patients enter a stage of few or no symptoms after treatment, but with persistent carriage and subsequent risk for spread of resistance in the community [2].

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY FOR ACUTE NGU

The European 2016 NGU treatment guideline recommends that azithromycin 1 g not be used as first-line therapy, due to the accumulating evidence that this regimen promotes macrolide antimicrobial resistance in M. genitalium and is only 87% effective in eradicating macrolide-sensitive infection [1, 4, 19]. This is contrary to the 2015 CDC sexually transmitted infection (STD) treatment guidelines and United Kingdom 2015 NGU treatment guidelines, which recommend azithromycin 1 g for NGU [44, 48]. These differences in treatment approach reflect how rapidly the evidence base concerning treatment of M. genitalium is changing. Given the new evidence and the imperative of good antimicrobial stewardship, the continued recommendation of azithromycin 1 g as first-line treatment for NGU in the United States and the United Kingdom should be reviewed [44, 48, 49]. There is some evidence that in macrolide-sensitive infection, azithromycin 500 mg followed by 250 mg for 4 days may be more effective and less likely to promote macrolide antimicrobial resistance, particularly if prescribed after a 7-day course of doxycycline [19, 50–52]. However, a recent retrospective study from Australia suggests that the extended azithromycin regimen may not be more effective than 1 g and also may be associated with promotion of macrolide antimicrobial resistance [4, 53]. It is unclear why the observations differ and may reflect differences in the populations studied, with the latter including high-risk MSM, in whom three-quarters of pretreatment M. genitalium strains were macrolide resistant [53].

The European guideline recommends doxycycline 100 mg bid for 7 days as first-line therapy for NGU [19]. It is effective against chlamydia and, although it has markedly reduced efficacy against M. genitalium in treatment of wild-type infection compared to azithromycin 1 g, it does not appear to promote tetracycline resistance. It also has the potential benefit of reducing bacterial load, which would theoretically reduce the risk of selection for both macrolide and quinolone resistance as a result of heterotypic resistance if these antimicrobials are subsequently prescribed in men who fail therapy [54, 55]. This is supported by the observational data from Anagrius et al and Gesink et al in which no macrolide antimicrobial resistance developed with the extended azithromycin after pretreatment with doxycycline [50, 52]. Doxycycline efficacy also would not be affected by the presence of macrolide resistance; thus, some macrolide resistant infections will also be eradicated.

In summary, the recommendation of azithromycin 1 g as first-line treatment for NGU by the United States and the United Kingdom should be reviewed. Given the recent conflicting evidence on the efficacy of the extended 5-day regimen as first-line therapy, it may be that doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days is the most logical choice for use as first-line therapy.

New Investigational Antimicrobials and Combination Therapy

Increasing rates of M. genitalium treatment failure due to antimicrobial resistance have resulted in an urgent need for new therapies, which Bradshaw et al discuss in detail elsewhere in this supplement [4].

Management of Persistent or Recurrent NGU Following Initial Treatment

In 15%–25% of men, persistent or recurrent symptoms can occur. While M. genitalium is an important cause, other etiologies such as T. vaginalis need to be considered. The management of persistent or recurrent NGU can be challenging, particularly in the absence of diagnostic testing for M. genitalium [19]. In men initially treated with doxycycline, the extended 5-day azithromycin regimen is recommended by the European guidelines [19]. The 2015 CDC STD treatment guidelines recommend azithromycin 1 g if the patient was initially treated with doxycycline, which given the recent change in the evidence base, should be reviewed [44, 49]. If azithromycin had been used as first-line therapy, then moxifloxacin 400 mg daily for 7–14 days is recommended [19, 44], although quinolone antimicrobial resistance is also beginning to emerge [2, 4]. A possible alternative approach in treatment failures initially treated with azithromycin, although not recommended in either the European or CDC treatment guidelines, is the use of doxycycline as second-line therapy. Doxycycline is 30%–40% effective in eradicating M. genitalium irrespective of whether or not it is macrolide and/or quinolone resistant [2, 4]. Moreover, doxycycline is significantly cheaper than moxifloxacin and may be safer.

In Europe, the concurrent administration of metronidazole is recommended in all men with NGU who fail first-line therapy, whereas in the United States this is only recommended in men who have sex with women where T. vaginalis is prevalent [19, 44].

In summary, the management of persistent and recurrent NGU is challenging in the absence of M. genitalium NAAT and antimicrobial resistance testing.

PARTNER NOTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT

Men With NGU

The primary aims of partner notification and treatment are to prevent reinfection of the index male, prevent complications of the infection in the partner(s), and reduce onward transmission. All current partner(s) should be tested and treated with the same treatment as the index patient and advised not to be sexually active until all have completed treatment and symptoms have resolved [2, 19]. This should be undertaken sensitively considering sociocultural issues and avoiding stigma [19]. This is a complex issue given the limited availability of M. genitalium NAATs, the poor efficacy of current first-line treatment regimens, the prevalence of M. genitalium macrolide resistance globally, and the observation that not all sexual partners are infected. The issue is even more complicated for other noncurrent partners in the 3 months prior to the index male’s diagnosis. Table 1 details the advantages of M. genitalium NAAT testing with or without antimicrobial resistance testing in managing partners of men presenting with symptoms of NGU. In the United States, there is no diagnostic test for M. genitalium that is cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for commercial use.

In summary, current sexual partners should be tested and treated with the same treatment as the index patient.

Persistent and Recurrent NGU

It is currently recommended that all recent sexual partner(s) (see above) should be tested for chlamydia and gonorrhea using a NAAT and offered treatment [19, 44]. In men with persistent NGU, in whom M. genitalium is common, in the absence of specific M. genitalium diagnostic testing it is unclear whether the partner should be re-treated. It is likely that re-treatment of the sexual partner with the same antimicrobial therapy effective in the index case will be beneficial if persistent/recurrent NGU in the index case resolves following extended therapy, but subsequently recurs following sexual intercourse [19].

OTHER CLINICAL SYNDROMES POTENTIALLY ASSOCIATED WITH M. GENITALIUM

Proctitis

Proctitis is characterized clinically as rectal pain and/or rectal discharge. There is one large study that demonstrates the association of M. genitalium with proctitis. Among 154 Australian MSM with proctitis, Bissessor et al [56] reported a M. genitalium prevalence of 12%; N. gonorrhoeae, 25%; chlamydia, 19%; and herpes simplex virus, 18%. Mycoplasma genitalium was the only bacterial infection significantly associated with HIV infection in this study. Soni et al made the same observation in a survey of asymptomatic rectal carriage of STI pathogens [24]. Bissessor et al [56] also found that the rectal M. genitalium bacterial load was significantly higher in men with proctitis compared to asymptomatic men. This finding parallels the results of quantitative studies of M. genitalium in urethral infections; however, treatment outcomes were not evaluated. There are no specific studies that have evaluated treatment effectiveness for M. genitalium proctitis.

Prostatitis

There is some data on the association of M. genitalium and prostatitis. Krieger et al [57] reported that biopsies from 4% of 135 men with chronic prostatitis were positive by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for M. genitalium. Mo et al [58] recently described evaluation of 235 Chinese men with prostatitis and 152 asymptomatic STI clinic controls who underwent the same specimen collection procedures including prostate massage. Using a quantitative M. genitalium PCR assay, 10% of men with clinical prostatitis had evidence of M. genitalium infection of the prostate based on detection of the organism only in expressed prostatic secretions and/or the post–prostatic massage urine specimen or 4-fold higher M. genitalium DNA concentrations in these specimens relative to concentrations in first-stream or midstream urine specimens. Only 3% of controls had evidence of M. genitalium in the prostate (P = .005). These data suggest that M. genitalium can be a cause of prostatitis in a small proportion of cases, but this requires confirmation.

Epididymitis

Given the parallels between clinical syndromes caused by C. trachomatis and M. genitalium, it would be expected that M. genitalium infection may result in epididymitis. Hamasuna [59] described a patient with classic epididymitis from whom M. genitalium was the only known pathogen identified. There was no clinical response to minocycline and cephalosporin antibiotics, but improvement was noted following the administration of levofloxacin. Ito et al [60] recently reported on 56 cases of epididymitis in men <40 years old. Chlamydia trachomatis was associated with 50% of the cases while M. genitalium was present in 8%. Although there are limited data, it is likely M. genitalium may cause epididymitis, though less commonly than C. trachomatis.

Syndromes Possibly Associated With M. genitalium

Given the association of C. trachomatis with postinfectious arthritis, there is a possibility that M. genitalium would be associated with this or other syndromes involving joint inflammation [61, 62]. Although Horner et al had reported that M. genitalium is associated with balanoposthitis, such an association was not observed in the recent study by Ito et al [43, 63].

HIV TRANSMISSION

Mycoplasma genitalium infection is associated with HIV acquisition in women [64], which may be due to its ability to induce a proinflammatory response. Genital tract infections can cause an inflammatory discharge, which has been associated with increased HIV shedding [65]. Whether M. genitalium–infected men practicing unprotected anal intercourse may be more likely to be at an increased risk of HIV acquisition and, if HIV infected, more likely to transmit HIV during unprotected anal and insertive oral intercourse is as yet unknown. The inflammatory response associated with M. genitalium infection in men is less marked than that observed with chlamydia and gonorrhea and one small study of men with NGU (M. genitalium was not tested for) did not demonstrate an increase in HIV load in the semen compared to controls. [66]

SCREENING FOR M. GENITALIUM IN MEN

In the absence of randomized controlled trials demonstrating cost effectiveness, screening asymptomatic men for M. genitalium cannot be recommended.

CONCLUSIONS

Mycoplasma genitalium is one of the major causes of NGU worldwide but an uncommon sexually transmitted infection in the general population. Effective treatment is complicated as macrolide antimicrobial resistance is now common in many countries, conceivably as a result of widespread use of azithromycin 1 g to treat STIs, and the limited availability of diagnostic tests for M. genitalium. Improved outcomes in men with NGU and better antimicrobial stewardship are likely to arise from introduction of diagnostic M. genitalium NAAT testing, including antimicrobial resistance testing in men with symptoms of NGU as well as in their current sexual partner(s). The cost effectiveness of these approaches needs further evaluation.

Notes

Disclaimer. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service (NHS), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the Department of Health, or Public Health England (PHE).

Financial support. This work is an outcome of a Mycoplasma genitalium Experts Technical Consultation that was supported by the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (contract number HHSN272201300012I), with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinical Trials Group. Additionally, this work was supported by the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol in partnership with PHE. D. H. M. is funded by the US National Institutes of Health (grant numbers R01 HD086794 and R01 AI097080).

Supplement sponsorship. This work is part of a supplement sponsored by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Sexually Transmitted Infections Clinical Trials Unit and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Potential conflicts of interest. P. J. H. reports personal fees from Crown Prosecution service; personal fees from the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV; grants from Mast Group Ltd; and nonfinancial support from Hologic. In addition, P. J. H. has a patent, “A sialidase spot test to diagnose bacterial vaginosis,” issued to the University of Bristol. D. H. M. reports no potential conflicts. Both authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Lau A, Bradshaw CS, Lewis D et al. . The efficacy of azithromycin for the treatment of genital Mycoplasma genitalium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1389–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Moi H. 2016 European guideline on Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016; 30:1650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horner P, Saunders J. Should azithromycin 1 g be abandoned as a treatment for bacterial STIs? The case for and against. Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93:85–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bradshaw C, Jensen J, Waites KB. New horizons in Mycoplasma genitalium treatment. J Infect Dis 2017;216(Suppl 2):S412–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sonnenberg P, Ison CA, Clifton S et al. . Epidemiology of Mycoplasma genitalium in British men and women aged 16–44 years: evidence from the Third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL-3). Int J Epidemiol 2015; 44:1982–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manhart LE, Holmes KK, Hughes JP, Houston LS, Totten PA. Mycoplasma genitalium among young adults in the United States: an emerging sexually transmitted infection. Am J Public Health 2007; 97:1118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andersen B, Sokolowski I, Østergaard L, Kjølseth Møller J, Olesen F, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence and behavioural risk factors in the general population. Sex Transm Infect 2007; 83:237–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Public Health England. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): annual data tables 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables. Accessed 3 February 2017.

- 9. Leung A, Eastick K, Haddon LE, Horn CK, Ahuja D, Horner PJ. Mycoplasma genitalium is associated with symptomatic urethritis. Int J STD AIDS 2006; 17:285–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox C, McKenna JP, Watt AP, Coyle PV. Ureaplasma parvum and Mycoplasma genitalium are found to be significantly associated with microscopy-confirmed urethritis in a routine genitourinary medicine setting. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27:861–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khatib N, Bradbury C, Chalker V et al. . Prevalence of Trichomonas vaginalis, Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum in men with urethritis attending an urban sexual health clinic. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26:388–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reynolds-Wright J, Verrall F, Hassan-Ibrahim M, Soni S. Implementing a test and treat pathway for Mycoplasma genitalium in men with urethritis attending a GUM clinic. Sex Transm Infect 2016; 92(suppl 1):A12. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGowin CL, Totten PA. The unique microbiology and molecular pathogenesis of Mycoplasma genitalium. J Infect Dis 2017;216(Suppl):S382–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tosh AK, Van Der Pol B, Fortenberry JD et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium among adolescent women and their partners. J Adolesc Health 2007; 40:412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oakeshott P, Aghaizu A, Hay P et al. . Is Mycoplasma genitalium in women the “new chlamydia?” A community-based prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51:1160–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vandepitte J, Weiss HA, Kyakuwa N et al. . Natural history of Mycoplasma genitalium infection in a cohort of female sex workers in Kampala, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40:422–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smieszek T, White PJ. Apparently-different clearance rates from cohort studies of Mycoplasma genitalium are consistent after accounting for incidence of infection, recurrent infection, and study design. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0149087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Black V, Magooa P, Radebe F, Myers M, Pillay C, Lewis DA. The detection of urethritis pathogens among patients with the male urethritis syndrome, genital ulcer syndrome and HIV voluntary counselling and testing clients: should South Africa’s syndromic management approach be revised? Sex Transm Infect 2008; 84:254–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horner PJ, Blee K, Falk L, van der Meijden W, Moi H. 2016 European guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27:928–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seña AC, Lensing S, Rompalo A et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in men with nongonococcal urethritis: predictors and persistence after therapy. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wetmore CM, Manhart LE, Lowens MS et al. . Demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of men with nongonococcal urethritis differ by etiology: a case-comparison study. Sex Transm Dis 2011; 38:180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottesman T, Yossepowitch O, Samra Z, Rosenberg S, Dan M. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium in men with urethritis and in high risk asymptomatic males in Tel Aviv: a prospective study. Int J STD AIDS 2017; 28:127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK, Lister NA, Chen SJ, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN. Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men at male-only saunas. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:432–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soni S, Alexander S, Verlander N et al. . The prevalence of urethral and rectal Mycoplasma genitalium and its associations in men who have sex with men attending a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect 2010; 86:21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zheng BJ, Yin YP, Han Y et al. . The prevalence of urethral and rectal Mycoplasma genitalium among men who have sex with men in China, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014; 14:195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fuchs W, Kreuter A, Hellmich M et al. . Asymptomatic anal sexually transmitted infections in HIV-positive men attending anal cancer screening. Br J Dermatol 2016; 174:831–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rane VS, Fairley CK, Weerakoon A et al. . Characteristics of acute nongonococcal urethritis in men differ by sexual preference. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:2971–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mezzini TM, Waddell RG, Douglas RJ, Sadlon TA. Mycoplasma genitalium: prevalence in men presenting with urethritis to a South Australian public sexual health clinic. Intern Med J 2013; 43:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from Chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24:498–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGowin CL, Annan RS, Quayle AJ et al. . Persistent Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human endocervical epithelial cells elicits chronic inflammatory cytokine secretion. Infect Immun 2012; 80:3842–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Althaus CL, Heijne JC, Low N. Towards more robust estimates of the transmissibility of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis 2012; 39:402–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Katz BP. Estimating transmission probabilities for chlamydial infection. Stat Med 1992; 11:565–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quinn TC, Gaydos C, Shepherd M et al. . Epidemiologic and microbiologic correlates of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in sexual partnerships. JAMA 1996; 276:1737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thurman AR, Musatovova O, Perdue S, Shain RN, Baseman JG, Baseman JB. Mycoplasma genitalium symptoms, concordance and treatment in high-risk sexual dyads. Int J STD AIDS 2010; 21:177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Walker J, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS et al. . The difference in determinants of Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium in a sample of young Australian women. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yoshida T, Deguchi T, Ito M, Maeda S, Tamaki M, Ishiko H. Quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium from first-pass urine of men with urethritis and asymptomatic men by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:1451–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jensen JS, Björnelius E, Dohn B, Lidbrink P. Use of TaqMan 5′ nuclease real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium DNA in males with and without urethritis who were attendees at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:683–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Falk L, Fredlund H, Jensen JS. Symptomatic urethritis is more prevalent in men infected with Mycoplasma genitalium than with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect 2004; 80:289–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Napierala M, Munson E, Wenten D et al. . Detection of Mycoplasma genitalium from male primary urine specimens: an epidemiologic dichotomy with Trichomonas vaginalis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2015; 82:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S et al. . Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL). Lancet 2013; 382:1795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bradshaw CS, Fairley CK, Lister NA, Chen SJ, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN. Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men at male-only saunas. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:432–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deguchi T, Yasuda M, Yokoi S et al. . Failure to detect Mycoplasma genitalium in the pharynges of female sex workers in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2009; 15:410–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ito S, Hanaoka N, Shimuta K et al. . Male non-gonococcal urethritis: From microbiological etiologies to demographic and clinical features. Int J Urol 2016; 23:325–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines http://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Accessed 3 February 2017.

- 45. Wiggins RC, Holmes CH, Andersson M, Ibrahim F, Low N, Horner PJ. Quantifying leukocytes in first catch urine provides new insights into our understanding of symptomatic and asymptomatic urethritis. Int J STD AIDS 2006; 17:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moi H, Reinton N, Moghaddam A. Mycoplasma genitalium is associated with symptomatic and asymptomatic non-gonococcal urethritis in men. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pond MJ, Nori AV, Patel S et al. . Performance evaluation of automated urine microscopy as a rapid, non-invasive approach for the diagnosis of non-gonococcal urethritis. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91:165–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haddow LJ, Bunn A, Copas AJ et al. . Polymorph count for predicting non-gonococcal urethral infection: a model using Chlamydia trachomatis diagnosed by ligase chain reaction. Sex Transm Infect 2004; 80:198–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Horner P, Blee K, O’Mahony C, Muir P, Evans C, Radcliffe K; Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV 2015 UK National Guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27:85–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Horner PJ. Editorial commentary: Mycoplasma genitalium and declining treatment efficacy of azithromycin 1 g: what can we do? Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1400–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Anagrius C, Loré B, Jensen JS. Treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium. Observations from a Swedish STD clinic. PLoS One 2013; 8:e61481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Falk L, Enger M, Jensen JS. Time to eradication of Mycoplasma genitalium after antibiotic treatment in men and women. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70:3134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gesink D, Racey CS, Seah C et al. . Mycoplasma genitalium in Toronto, Ont: Estimates of prevalence and macrolide resistance. Can Fam Physician 2016; 62:e96–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Read TR, Fairley CK, Tabrizi SN et al. . Azithromycin 1.5g over 5 days compared to 1g single dose in urethral Mycoplasma genitalium: impact on treatment outcome and resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2016. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mena LA, Mroczkowski TF, Nsuami M, Martin DH. A randomized comparison of azithromycin and doxycycline for the treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium–positive urethritis in men. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:1649–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jensen JS, Bradshaw C. Management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections—can we hit a moving target? BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bissessor M, Tabrizi SN, Bradshaw CS et al. . The contribution of Mycoplasma genitalium to the aetiology of sexually acquired infectious proctitis in men who have sex with men. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22:260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krieger JN, Riley DE, Roberts MC, Berger RE. Prokaryotic DNA sequences in patients with chronic idiopathic prostatitis. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:3120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mo X, Zhu C, Gan J et al. . Prevalence and correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium infection among prostatitis patients in Shanghai, China. Sex Health 2016. doi:10.1071/sh15155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hamasuna R. Editorial comment from Dr Hamasuna to “prevalence of genital mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas in men younger than 40 years-of-age with acute epididymitis.” Int J Urol 2012; 19:239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ito S, Tsuchiya T, Yasuda M, Yokoi S, Nakano M, Deguchi T. Prevalence of genital mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas in men younger than 40 years-of-age with acute epididymitis. Int J Urol 2012; 19:234–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chrisment D, Machelart I, Wirth G et al. . Reactive arthritis associated with Mycoplasma genitalium urethritis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 77:278–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Taylor-Robinson D, Gilroy CB, Horowitz S, Horowitz J. Mycoplasma genitalium in the joints of two patients with arthritis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1994; 13:1066–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Horner PJ, Taylor-Robinson D. Association of Mycoplasma genitalium with balanoposthitis in men with non-gonococcal urethritis. Sex Transm Infect 2011; 87:38–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mavedzenge SN, Van Der Pol B, Weiss HA et al. . The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV-1 acquisition in African women. AIDS 2012; 26:617–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Johnson LF, Lewis DA. The effect of genital tract infections on HIV-1 shedding in the genital tract: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35:946–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sadiq ST, Taylor S, Copas AJ et al. . The effects of urethritis on seminal plasma HIV-1 RNA loads in homosexual men not receiving antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect 2005; 81:120–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]