Abstract

Background.

In India, antimicrobial consumption is high, yet systematically collected data on the epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes of antimicrobial-resistant infections are limited.

Methods.

A prospective study of adults and children hospitalized for acute febrile illness was conducted between August 2013 and December 2015. In-hospital outcomes were recorded, and logistic regression was performed to identify independent predictors of community-onset antimicrobial-resistant infections.

Results.

Among 1524 patients hospitalized with acute febrile illness, 133 isolates were found among 115 patients with community-onset infections; 66 isolates (50.0%) were multidrug resistant and, of 33 isolates tested for carbapenem susceptibility, 12 (36%) were resistant. Multidrug-resistant infections were associated with recent antecedent antibiotic use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–19.7) and were independently associated with mortality (aOR, 6.06; 95% CI, 1.2–55.7).

Conclusion.

We found a high burden of community-onset antimicrobial-resistant infection among patients with acute febrile illness in India. Multidrug-resistant infection was associated with prior antibiotic use and an increased risk of mortality.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, community onset, clinical isolates, India.

The emergence of antimicrobial resistance has become a global crisis. Contributing factors include unregulated access to antimicrobials, clinical overuse, inadequate diagnosis, agricultural antimicrobial use, and ineffective infection control [1–3]. Management of life-threatening, drug-resistant bacterial infections is challenging. Therapeutic options are limited, often require parenteral administration, are costlier, and have more adverse effects. Drug-resistant infections also incur increased hospitalization costs, length of stay, and mortality. These issues are magnified in low-income and middle-income settings.

With a population of 1.2 billion, India is among the countries with greatest global bacterial disease burden [1]. Antimicrobial use is common in India and has increased dramatically over the past 20 years [3]. However, systematically collected data on antimicrobial resistance are limited in both inpatient and community settings. Knowledge of antimicrobial resistance patterns and the availability of appropriate antimicrobials are essential to prevent the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with drug-resistant infections.

Most studies to date have focused on single organisms or outbreaks rather than on broader evaluation of the epidemiology of bacterial infections [2, 4–7]. In 2009–2010, there was a worldwide emergence of an organism containing multiple resistance determinants, coined “New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases,” that in part originated from a tertiary care hospital in New Delhi [8]. The emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases highlighted the antimicrobial resistance problem in India, demonstrated how rapidly an organism can spread throughout the world, and highlighted the lack of systematically collected antimicrobial resistance data in India and most low-income and middle-income countries. While organisms expressing New Delhi metallo-β-lactamases may be the most well-known example of multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative organisms in India, numerous studies have long documented the rising rates of resistance to commonly used antimicrobials, as well as extended-spectrum β-lactamases, among gram-negative organisms [9, 10]. However, little is known about antimicrobial resistance in community-onset febrile illness.

Understanding antimicrobial resistance in India may serve several purposes [2], including generating evidence to support advocacy for the regulation of currently unregulated antibiotic prescription; to develop evidence-based treatment guidelines; to guide policy for antibiotic stewardship programs, which are presently nonexistent in most settings; and to emphasize the need for universal, standardized infection control guidelines. We aimed to describe the burden, risk factors, and outcomes of community-onset bacterial infection among adults and children admitted with acute febrile illness (AFI) to a large, public tertiary care facility in western India.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a study of adults and children admitted to Byramjee Jeejeebhoy Government Medical College and Sassoon General Hospitals (BJGMC-SGH) with AFI between July 2013 and December 2015. BJGMC-SGH is a 1400-bed tertiary care public teaching hospital in Pune, Maharashtra, serving a population of approximately 7 million in urban, semiurban, and rural areas. Eligible participants ages >6 months were identified from admission logbooks in inpatient medicine and pediatric wards, which were reviewed on working days for history of AFI. Patients with a self-reported or documented temperature of ≥38ºC for a duration of ≥24 hours were approached for enrollment. Patients transferred directly from another healthcare facility to BJGMC-SGH or those reporting hospitalization or surgery in the 3 months before admission were excluded.

Informed consent was obtained from eligible adult patients and from the legal guardian of eligible children aged <18 years; assent was obtained for children aged >12 years. This study was approved by the BJGMC-SGH Ethics Committee and the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Assessments

A dedicated study physician and social worker recorded each participant’s clinical history by means of a standardized method, and provisional admission diagnoses made by the hospital clinical team were recorded. Treating clinicians used a case record form to record clinical features at admission and discharge, as well as the results of routine laboratory investigations. On admission, the study team collected blood from all participants as per study protocol. Participants’ skin was cleansed, and a 5-mL blood sample was collected for aerobic and anaerobic blood culture. Additional specimens were collected to determine AFI etiology. All participants with unknown human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status were offered and consented to undergo rapid HIV testing. In addition to systematically collection blood specimens at admission for culture, the study team used medical and laboratory records to abstract all additional bacterial culture results for any type of specimen as part of routine care until discharge.

Laboratory Procedures

Bactec standard aerobic bottles were loaded into the Bactec Microbial Detection system (Becton Dickinson) and incubated for 5 days. Standard methods were used to identify bloodstream isolates, which included subculture in blood and MacConkey agar. Bacterial species identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed according to Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (Wayne, PA) guidelines, using the Phoenix Automated Microbiology System (Becton Dickinson) [11]. For cultures other than those of blood samples, specimens were directly plated onto blood and MacConkey agar and underwent manual identification of bacterial species and testing for drug susceptibility. During the study, the laboratory had positive results of relevant external quality assurance assessments by the College of American Pathologists and the Viral Quality Assurance program of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group.

Study Outcomes and Definitions

Primary outcomes were culture-positive community-onset infection and detection of MDR pathogens. Isolates identified as coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, Micrococcus species, Dermacoccus species, Bacillus species, and other environmental flora were considered to be contaminants and excluded from analysis. Additionally, enterococcus isolated in urine culture was considered to be a contaminant. Community-onset and hospital-onset infections were defined by the presence of positive clinical cultures obtained ≤2 and >2 days after admission, respectively, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention surveillance definitions [12, 13]. Pathogenic isolates were classified as MDR according to consensus definitions from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [11]. MDR was defined as nonsusceptibility to at least 1 agent in at least 3 antimicrobial categories specific to the following groupings: Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus species, Enterobacteriaceae other than Shigella and Salmonella, Pseudomonas species, and Acinetobacter species. As consensus definitions did not include Salmonella, Shigella, and Streptococcus species, existing definitions from other sources were used. Salmonella isolates resistant to ≥2 of the following antimicrobials were classified as MDR: amoxicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, or tetracyclines. Shigella isolates resistant to ≥3 classes of antimicrobials were classified as MDR. Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates not susceptible to penicillin and at least 2 other non–β-lactam antimicrobial classes were classified as MDR [14]. Carbapenem-resistant gram-negative rods (GNRs) with insufficient data to otherwise meet the above guidelines were also considered to be MDR. Secondary outcomes included length of hospitalization and in-hospital all-cause mortality. Severe malnutrition among children was defined as a weight-for-height score <3 standard deviations below the median, using the World Health Organization growth charts for children aged <5 years and the Indian Academy of Pediatrics growth charts for children ages 5–12 years [15].

Analyses

Data were entered into Microsoft Access software. Baseline categorical and continuous variables are summarized using proportions and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), respectively, and compared using the Fisher exact test or Wilcoxon rank sum test as appropriate; P values of <.05 were deemed statistically significant. To evaluate predictors for MDR organisms, we assessed selected clinical and demographic variables, using univariate regression and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Multivariate models were fitted to estimate the odds ratio (OR) that adjusted for covariates with P values of <.1 in univariate analysis, covariates known to be associated with a risk of infection with MDR organisms, and demographic variables. A multivariable model was created to evaluate the association of community-onset infection with MDR organisms, with adjustment for demographic variables and the type of infection. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.2.1; available at: http://www.cran.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

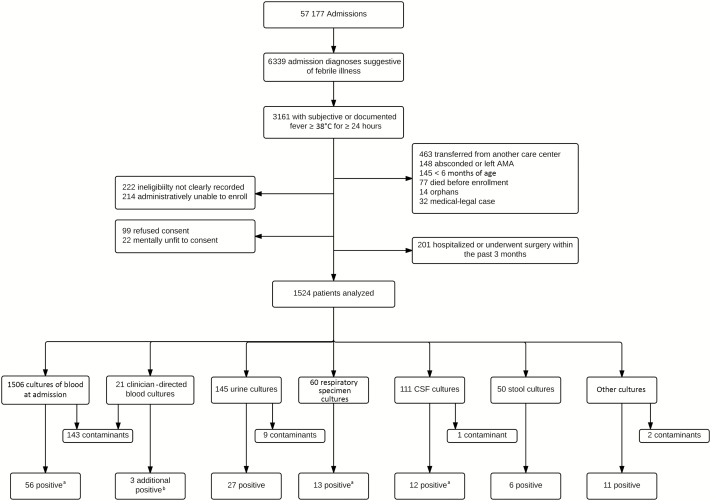

Of 57177 patients admitted to BJGMC-SGH medicine and pediatric wards during the study period, 6339 with admission logbook diagnoses suggestive of AFI were screened. Of these 6339 patients, 3161 met criteria for AFI, and 1524 met study-specific inclusion criteria. Reasons for noninclusion are shown in Figure 1. The study population comprised 842 adults and adolescents (ie, individuals aged ≥12 years; median age, 29 years [IQR, 21–45 years]) and 682 children ages 6 months through 11 years (median age, 2 years [IQR, 1–6 years]). Overall, 58% were male, 52% received intravenous antibiotics before a blood specimen was obtained for culture, and 12% of adults and 1% of children had documented or reported HIV infection (Table 1). Patients who received in-hospital antibiotics prior to collection of blood specimens for culture were more likely to be adults (P < .01) and less likely to be admitted to the ICU (P = .01).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study enrollments and collection of cultures among adults and children hospitalized for acute febrile illness (AFI) in Pune, India. AMA, against medical advice; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid. aOne blood culture, 2 respiratory specimen cultures, and 2 CSF cultures grew 2 organisms. bResults of 4 cultures were positive; 1 positive result was already identified by culture of a blood specimen obtained at admission.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Adults and Children Hospitalized With Acute Febrile Illness, by Isolation of a Bacterial Pathogen From Any Clinical Culture

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 1524) | Pathogen Isolated | Adults (n = 842), Pathogen Isolated | Children (n = 682), Pathogen Isolated | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 1409) | Yes (n = 115) | P | No (n = 777) | Yes (n = 65) |

P | No (n = 632) | Yes (n = 50) | P | ||

| Age, y | 17 (3–31) | 17 (3–30) | 21 (3–43.5) | .06 | 28 (21–43) | 40 (30–56) | <.01 | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–6) | .52 |

| Male sex | 882 (58) | 823 (58) | 59 (51) | .14 | 466 (60) | 36 (55) | .51 | 357 (56) | 23 (46) | .18 |

| Alcohol use (adults only)a | … | … | … | 66 (10) | 10 (24) | .02 | … | … | ||

| Smoking (adults only)a | … | … | … | 81 (13) | 3 (7) | .46 | … | … | ||

| Income <5000 rupees/mo | 605 (40) | 538 (38) | 67 (58) | <.01 | 281 (36) | 38 (58) | <.01 | 257 (41) | 29 (58) | .02 |

| Blood cultures performed before antibiotic useb | 712 (48) | 658 (48) | 54 (48) | 1 | 278 (37) | 21 (34) | .68 | 380 (62) | 33 (66) | .65 |

| Diabetes mellitusa | 42 (3) | 36 (3) | 6 (9) | .03 | 35 (5) | 6 (14) | .03 | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| HIV positivec | 109 (13) | 95 (13) | 14 (19) | .1 | 83 (12) | 13 (23) | .04 | 12 (18) | 1 (7) | .44 |

| Severe malnutrition (children only) | … | … | … | … | … | 116 (21) | 4 (9) | .05 | ||

| Antibiotic use within past mo | 357 (23) | 332 (24) | 25 (22) | .73 | 203 (26) | 17 (26) | 1 | 129 (20) | 8 (16) | .58 |

| Antibiotic use within past wk | 324 (21) | 302 (21) | 22 (19) | .64 | 187 (24) | 16 (25) | .88 | 115 (18) | 6 (12) | .34 |

| Length of stay, d | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–7) | 5 (3–12) | <.01 | 3 (2–5) | 4 (3–7.25) | <.01 | 6 (4–10) | 6.5 (4–13.8) | .23 |

| In-hospital mortality | 119 (8) | 101 (7) | 18 (16) | <.01 | 53 (7) | 10 (16) | .02 | 48 (8) | 8 (17) | .05 |

Data are median (interquartile range) or no. (%) of participants. Adults and adolescents are defined as participants aged ≥12 years. Children are defined as participants aged 6 months to 12 years. Nonpathogenic isolates have been excluded.

aData for alcoholism, smoking, and diabetes were not collected for the first 5 months of the study. Percentages reflect a denominator of 688 adults and 545 children.

bInformation was not available for 41 patients.

cHuman immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status was known for 746 adults; data were not systematically collected for all children.

Any Bacterial Infection

Of 1524 participants admitted with AFI, blood specimens were collected from 1506 patients at admission for culture, of whom 203 had positive culture results, including 148 with contaminants and 59 (4%) with noncontaminant organisms. Cultures for 1 patient grew 2 pathogenic organisms. An additional 69 patients had community-onset infections with positive results of cultures involving specimens from other sites, including 27 cultures of urine specimens, 15 cultures of respiratory specimens, 14 cultures of CSF specimens, and 17 cultures of specimens from other sources; 4 patients had 2 isolates detected on culture. Thus, 133 pathogenic isolates were obtained from 115 patients (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1), comprising 97 patients with monomicrobial infections, 15 patients with polymicrobial infections, and 3 patients with the same organism recovered from 2 different specimen sources. Patients with culture-positive community-onset infections represented 7% of the study population, which comprised 65 adults/adolescents (8%) and 50 children (7%). Patients with a culture-positive community-onset bacterial infection were more likely to report lower income (P < .01) and diabetes mellitus (P = .03) than those with culture-negative AFI (Table 1). Among adults and adolescents, those with a culture-positive bacterial infection were older (median age, 40 years [IQR, 30–56 years] vs 28 years [IQR, 21–43 years]; P < .01), more likely to report alcohol abuse (P = .02), have lower income (P < .01), have a longer hospitalization duration (P < .01), and have higher in-hospital mortality (P = .02) than those with culture-negative AFI (Table 1). Among children, we observed lower household income (P = .02) and higher in-hospital mortality (P = .05) in those with culture-positive community-onset bacterial infection.

Table 2.

Species of Community-Onset Pathogenic Bacterial Isolates Recovered on Culture Among 115 Patients, by Clinical Specimen Cultured

| Organism | Overall (n = 133) | Blood, Collected Before Antibiotic Treatment (n = 25) | Blood, Collected After Antibiotic Treatment (n = 35) | CSF (n = 14)a | Urine (n = 27) | Respiratory (n = 15)b | Other (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative rods | |||||||

| Escherichia coli | 31 (23) | … | 9 (26) | 2 (14) | 12 (44) | 3 (20) | 5 (29) |

| Acinetobacter species | 18 (13) | 7 (28) | 6 (18) | 2 (14) | 2 (7) | 1 (7) | … |

| Pseudomonas species | 12 (9) | 1 (4) | … | 3 (21) | 3 (11) | 2 (13) | 3 (18) |

| Klebsiella species | 11 (8) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 2 (14) | 4 (15) | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Enterobacter | 7 (5) | … | … | 1 (7) | 3 (11) | 2 (13) | 1 (6) |

| Unspecified | 5 (4) | … | 1 (3) | 1 (7) | 1 (4) | 2 (13) | … |

| Burkholderia cepacia | 4 (3) | … | 4 (12) | … | … | … | … |

| Citrobacter | 4 (3) | … | … | … | 2 (7) | 2 (13) | … |

| Salmonella species | 2 (2) | 2 (8) | … | … | … | … | … |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis | 3 (2) | 3 (12) | … | … | … | … | … |

| Shigella flexneri | 2 (1) | 1 (4) | … | … | … | … | 1 (6) |

| Pasteurella aerogenes | 1 (1) | … | 1 (3) | … | … | … | … |

| Vibrio cholera | 1 (1) | … | … | … | … | … | 1 (6) |

| Aeromonas species | 1 (1) | … | 1 (3) | … | … | … | … |

| Gram-positive cocci | |||||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 12 (9) | 4 (16) | 2 (6) | 1 (7) | … | 1 (7) | 4 (23) |

| Enterococcus species | 6 (4) | 4 (16) | 2 (6) | … | … | … | … |

| Streptococcus species | 6 (4) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) | 1 (7) | … | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Aerococcus species | 4 (3) | 1 (4) | 3 (9) | … | … | … | … |

| Rhodococcus equi | 2 (1) | … | 2 (3) | … | … | … | … |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 (1) | … | … | 1 (7) | … | … | … |

Data are no. (%) of clinical cultures.

aCerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens were obtained from 12 patients; cultures for 2 patients were mixed.

bRespiratory specimens were obtained from 13 patients; cultures from 2 patients were mixed.

Of 133 bacterial pathogenic isolates from patients with community-onset infections, 102 (77%) were GNR, primarily composed of Enterobacteriaceae (n = 57; predominantly Escherichia coli [31 {23%}], Klebsiella [11 {8%}], Acinetobacter (18 {13%}], and Pseudomonas [12 {9%}]); 31 pathogenic isolates were gram-positive organisms, primarily S. aureus (12 [9%]), Enterococcus (6 [4%]), and Streptococcus species 6 (4%; Table 2). E. coli was the predominant species in urinary tract (12 [44.4%]) and respiratory (3 [20%]) specimens.

Among 1524 enrolled patients, 140 isolates were recovered from 105 with hospital-onset infections. The species of hospital-onset bacterial isolates, by specimen source and antimicrobial-susceptibility patterns, are described in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2. Interestingly, there were similar species and high MDR prevalence noted among GNR isolated from patients with hospital-onset or community-onset infections. The species breakdown of the 155 contaminant isolates obtained from 148 participants was as follows: 64 were coagulase-negative Staphylococcus species, 31 were Micrococcus or Dermacoccus species, 14 were Bacillus species, 8 were Enterococcus from urine specimens, and 43 were other species (Supplementary Table 3). Among the 155 contaminant cultures, 143 were derived from blood. Hereafter we focus on community-onset infections.

Table 3.

Species of Hospital-Onset Pathogenic Bacterial Isolates Recovered on Culture Among 105 Patients, by Clinical Specimen Cultured

| Organism | Overall (n = 140) | Blood (n = 47) | CSF (n = 1) | Urine (n = 26) | Respiratory (n = 49) | Other (n = 17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-negative rods | ||||||

| Escherichia coli | 32 (23) | 9 (19) | … | 15 (58) | 4 (8) | 4 (23) |

| Acinetobacter species | 26 (19) | 14 (30) | 1 (100) | … | 10 (20) | 1 (6) |

| Klebsiella species | 20 (14) | 3 (6) | … | 1 (4) | 15 (31) | 1 (6) |

| Pseudomonas species | 18 (13) | 6 (13) | … | 2 (8) | 7 (14) | 3 (18) |

| Citrobacter | 13 (9) | 3 (6) | … | 7 (27) | 3 (6) | … |

| Enterobacter | 6 (4) | 1 (2) | … | … | 5 (10) | … |

| Unspecified | 6 (4) | 2 (4) | … | 1 (4) | 3 (6) | … |

| Gram-positive cocci | ||||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 8 (6) | 5 (11) | … | … | 1 (2) | 2 (12) |

| Enterococcus species | 5 (4) | 3 (6) | … | … | … | 2 (12) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | … | … | … | … |

| Streptococcus species (other) | 5 (4) | … | … | … | 1 (2) | 4 (23) |

Data are no. (%) of clinical cultures.

Abbreviation: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Bloodstream Infections

Of 115 patients with community-onset culture-positive bacterial infections, 59 (51%) had 60 confirmed bloodstream pathogens. The most common pathogenic isolates were Acinetobacter species (13 [21.7%]), followed by E. coli (9 [15%]; Table 2). We noted that blood culture positivity was similar among patients who did and those who did not receive antibiotics prior to collection of blood specimens for culture (P = .50).

Community-Onset MDR Bacterial Infection (Table 4)

Table 4.

Association of Clinical Factors With Multidrug Resistance Among 87 Patients With Community-Onset Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections

| Risk Factor | Community-Onset Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections, No. | Multidrug Resistance, No. With Risk Factor (% | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted ORa (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 44 | 27 (61) | 0.94 (.4–2.2) | 1 | 0.85 (.33–2.16) | .73 |

| Age | ||||||

| <12 y | 31 | 16 (52) | 0.51 (.2–1.2) | .17 | 0.7 (.24–2.03) | .51 |

| >50 y | 22 | 16 (73) | 1.89 (.7–5.5) | .31 | 1.29 (.38–4.63) | .69 |

| HIV seropositive | 12 | 6 (50) | 0.37 (.1–1.4) | .17 | … | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 | 4 (67) | 1.56 (.3–9.3) | 1 | … | |

| Severe malnutrition | 4 | 2 (50) | 1 (.1–8.3) | 1 | … | |

| Income <5000 rupees/mob | 56 | 38 (68) | 1.98 (.8–4.9) | .17 | … | |

| Vegetarian | 17 | 11 (65) | 1.15 (.4–3.5) | 1 | … | |

| Works with animals | 20 | 16 (80) | 3.05 (.9–10.1) | .07 | 3.14 (.96–12.39) | .07 |

| Farmer | 11 | 9 (82) | 3.1 (.6–15.3) | .19 | … | |

| Antibiotic use in past wk | 16 | 13 (81) | 3.17 (.8–12.1) | .09 | … | |

| Antibiotic use in past mo | 18 | 15 (83) | 3.85 (1–14.5) | .05 | 4.17 (1.19–19.7) | .04 |

| Prior visit to general practitioner | 43 | 28 (65) | 1.21 (.5–3.1) | .81 | … |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

aAdjusted for age, sex, and working with animals.

bFor children, parental income is reported.

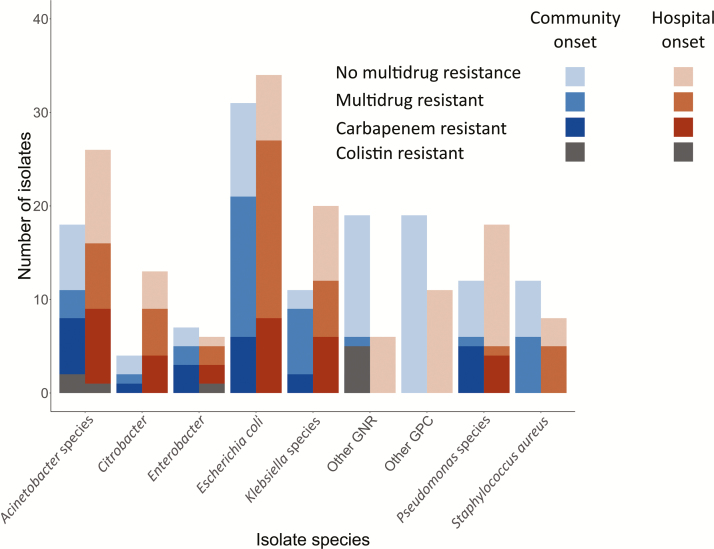

The majority of community-onset bacterial infections, involving 60 of 115 patients (52%) and 66 of 133 isolates (50%), were due to MDR organisms (Figure 2). Overall, the vast majority of MDR organisms (60 [91%]) were GNRs, representing 59% of all GNR isolates (see Supplementary Table 1 for complete source and resistance profiles). There were 43 Enterobacteriaceae isolates (75%) resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. Carbapenem resistance testing performed on 72 of 102 gram-negative isolates revealed that 27 (38%) were resistant to carbapenem. There were 4 gram-negative isolates resistant to all antibiotics tested other than colistin; 2 of 17 isolates (12%) were colistin resistant (Figure 2). Among 58 isolates from sources other than blood or CSF, 11 (16%) were not susceptible to any oral antibiotic. Of 12 S. aureus isolates, 6 (50%) were methicillin-resistant. None of the 6 enterococcus isolates were vancomycin resistant.

Figure 2.

Total, multidrug-resistant, and carbapenem-resistant pathogenic bacterial isolates among adults and children with microbiologically infection by species and classification as community versus hospital onset. Blue bars represent community-onset bacterial infections, orange bars represent hospital-onset bacterial infections. Increasing shading intensity represents broader antimicrobial resistance. Abbreviations: GPC, gram-positive cocci; GNR, gram-negative rod.

Three hundred and fifty-seven patients (23%) reported having received antibiotics ≤1 month prior to admission, and 324 (21%) reported having used them ≤1 week prior to admission. In a multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for age, sex, and working with animals, antibiotic use ≤1 month prior to hospital admission was associated with increased odds of infection with a MDR clinical isolate (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19–19.7; Table 4).

In-Hospital Outcomes

Patients with a culture-positive community-onset bacterial infection had a longer median hospital length of stay than culture-negative patients (5 vs 4 days; P < .01). A total of 119 of 1524 patients (8%) died during hospitalization. Of these 119 patients, 18 (15%) were found to have culture-positive community-onset infections, including 13 with bacteremia (2 also had positive results of a urine culture, and 1 had a positive result of a respiratory specimen culture), 1 had a positive respiratory specimen culture without bacteremia, and 1 each had positive results of CSF, pericardial, stool, and throat swab cultures. Among the 87 patients with a GNR isolate, 14 (16%) died during hospitalization. In-hospital mortality was more common among patients with MDR GNR isolates (23%) than among those with drug-susceptible GNR isolates (6%; OR, 4.5; 95% CI, .9–12.6). In a multivariable logistic regression model that adjusted for age, sex, and diagnosis of pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, and urinary tract infection, isolation of a MDR GNR was independently associated with mortality (aOR, 6.1; 95% CI, 1.2–55.7).

DISCUSSION

The disease burden due to drug-resistant organisms is high among patients hospitalized for community-onset AFI in India [16]. Our study of 1524 adults and children hospitalized with AFI is among the largest prospective surveillance studies of community-onset antimicrobial resistance in India [17] and identifies a number of key findings. We report high overall antimicrobial resistance burden among microbiologically confirmed community-onset bacterial infections. Community-onset, carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections were common, and isolates resistant to colistin were also detected [5]. We also observed a 5-fold increased risk of mortality associated with community-onset MDR GNR infections.

Only 4% of patients were found to have bacteremia, despite systematic and clinician-directed collection of blood specimens for culture. Although this is lower than the bacteremia rate in studies conducted in Africa, similar studies of patients with AFI in India and Southeast Asia have shown bacteremia in 0%–6% of patients [18–21]. Patients who received antibiotics prior to blood culture collection were less ill and more likely to be an adult but did not have any difference in frequencies of positive culture results as compared to patients who underwent collection of a blood specimen for culture prior to antibiotic administration. E. coli was only isolated in cultures of blood specimens that were collected after antibiotic administration, and all were unsurprisingly MDR. However, Acinetobacter was isolated in blood cultures performed before and after antibiotic administration in nearly equal proportions. Furthermore, administration of antibiotics prior to collection of blood specimens for culture was not significant when added to the model of clinical factors associated with community-onset, MDR gram-negative bacterial infection.

Consistent with other studies, E. coli was the most common causative gram-negative bacterium [2, 16, 22–24]. Notably, the second most common pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii, is typically a hospital-acquired organism, yet it accounted for the majority of community-onset, MDR (particularly carbapenem-resistant) gram-negative bacterial infections. Acinetobacter appears to be a particularly prevalent infection in antimicrobial resistance studies in India. Furthermore, colistin-resistant gram-negative organisms and carbapenem-resistant organisms detected among community-onset bacterial infections indicate wide dissemination of MDR organisms in the environment in India [25]. Finally, as in other studies of E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from India [26–28], we found high rates of resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. As third-generation cephalosporins are currently commonly used as empirical antibiotics for suspected serious bacterial infections, these findings have major implications for empirical antimicrobial choice in inpatient settings. Notably, we observed that a greater than expected proportion of carbapenem-resistant organisms were susceptible to fluoroquinolones, which is likely due to Indian prescribing practices that discourage routine fluoroquinolone use, to reserve these drugs for management of drug-resistant tuberculosis [29, 30].

In contrast to emerging data from India, however, we observed a relatively low rate of infection due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus [31, 32]. We also noted very low rates of invasive pneumococcal infections. Notably, nearly half of our study population received intravenous antibiotics before a blood culture was performed, and close to one third of patients received oral antibiotics prior to hospitalization, which may explain this finding.

As in prior studies, we also observed that antimicrobial exposure is a risk factor for subsequent infection due to MDR GNR [9, 33, 34] and that such infections lead to adverse outcomes, including increased length of hospitalization and mortality [35, 36]. In fact, we observed a 6-fold higher mortality among patients with MDR gram-negative bacterial infections. Increased in-hospital mortality has also been observed in another study in India focused on Acinetobacter bloodstream infections [37].

Our study highlights several unique population characteristics that may identify target populations with AFI with possible bacterial infections for whom empirical treatment regimens may differ. These include febrile patients who are older, patients with diabetes mellitus, and those with history of alcohol abuse and lower income. We also observed a high rate of HIV infection (13%) among adult febrile patients with bacterial infections as compared to the community HIV infection rate of 0.21%. This is in part because our site has a collocated HIV treatment center on its premises and caters to a predominantly poor, urban population. Although our study did not identify malnutrition as a risk factor for MDR bacterial infections in children, the fact that >58000 neonatal deaths are estimated to be attributed to drug-resistant infections should inform that this vulnerable group be adequately managed with local formulary antimicrobials.

Taken together, our findings underscore the critical need to implement an evidence based antimicrobial stewardship program [38, 39]. Because mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance differ by organism, commonly implemented unilateral preventive approaches, such as isolation precautions, cohorting, and screening for asymptomatic carriage, targeting single organisms may be inadequate [40, 41]. Further, protecting existing antimicrobials against increasing resistance becomes a priority with increasing global antimicrobial consumption [3], the availability in India of inexpensive antibiotics without prescription, and the slow pace of new antimicrobial discovery. In India, the Chennai Declaration is an important step in this direction to scale up awareness among health professionals, policy makers, and the general public.

Our study has some limitations. This study does not reflect the overall epidemiology of bacterial infections and antimicrobial resistance patterns in the community because we enrolled patients hospitalized for AFI and thus selected for more–severely ill patients. In addition, we may have underestimated the burden of pathogenic bacterial infections. Although blood cultures were systematically performed for all participants, cultures from other sources were only performed according to the treating clinician’s discretion. Carbapenem resistance testing was not uniformly performed for clinician-directed cultures, involving primarily sources other than blood. Further, a sizeable proportion of participants received prior antibiotics. Despite these limitations, our study is one of few prospectively evaluating the epidemiology and drug resistance patterns of community-onset bacterial infections among adults and children.

In conclusion, our results indicate a high burden of bacterial infections and resistance to commonly used antimicrobials among patients hospitalized for AFI. Our findings support the urgent need to regulate antimicrobial use in the community, as well as in healthcare settings, so that existing antimicrobials may be preserved to combat serious bacterial infections. Furthermore, there is a staggering lack of data on adverse consequences of MDR bacterial infections in low-income and middle-income countries, where the problem is substantial [16, 42, 43]. Future studies should assess the burden of bacterial infections and drug resistance patterns in outpatient settings, to inform the choice of empirical antibiotics; the risk factors associated with acquisition or emergence of resistance; long-term morbidity and mortality; the impact of drug-susceptible and drug-resistant organisms on quality of life; and the risk factors for infection with these organisms.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank the study participants and study staff for their immense contribution.

V. M., An. K., D. K., Aa. K., JZ, AG conceived the study. V. M., A. C., An. K, San. K., D. K., R. B., V. D., Aa. K., P. R., San. K., S. J., Sav. K., J. S., C. V., U. B., V. K., and I. M. conducted the study and collected data. V. M., M. R., and I. M. performed data analyses. V. M. drafted the initial manuscript, and all authors assisted in the manuscript preparation and approved the manuscript. A. G. obtained funding for the study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Ujala Foundation, the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine and the Sacharuna Foundation, the Gilead Foundation, the Wyncote Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) BWI HIV Clinical Trials Unit (grant U01 AI069497 to V. M., N. S., San. K., U. B., V. K., I. M., and A. G.), and the UJMT Fogarty Global Health Fellows Program (NIH research training grant R25 TW009340 to M. R. and J. S. and NIH training grant T32 AI007291 to M. R.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganguly NK, Arora NK, Chandy SJ, et al. ; Global Antibiotic Resistance Partnership–India Working Group Rationalizing antibiotic use to limit antibiotic resistance in India. Indian J Med Res 2011; 134:281–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016; 387:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aggarwal P, Uppal B, Ghosh R, et al. Multi drug resistance and extended spectrum beta lactamases in clinical isolates of Shigella: A study from New Delhi, India. Travel Med Infect Dis 2016; 14:407–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kotwal A, Biswas D, Kakati B, Singh M. ESBL and MBL in cefepime resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: an update from a rural area in Northern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2016; 10:Dc09–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar R, Gupta N; Shalini Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever. Indian J Pediatr 2007; 74:39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaur A, Garg A, Prakash P, Anupurba S, Mohapatra TM. Observations on carbapenem resistance by minimum inhibitory concentration in nosocomial isolates of Acinetobacter species: an experience at a tertiary care hospital in North India. J Health Popul Nutr 2008; 26:183–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laxminarayan R, Heymann DL. Challenges of drug resistance in the developing world. BMJ 2012; 344:e1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hawser SP, Bouchillon SK, Hoban DJ, Badal RE, Hsueh PR, Paterson DL. Emergence of high levels of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing gram-negative bacilli in the Asia-Pacific region: data from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART) program, 2007. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:3280–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:268–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, et al. Health care–associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Identifying healthcare-associated infections (HAI) for NHSN surveillance. In: National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) patient safety component manual. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richter SS, Heilmann KP, Dohrn CL, Riahi F, Beekmann SE, Doern GV. Changing epidemiology of antimicrobial-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States, 2004–2005. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48:e23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khadilkar V, Yadav S, Agrawal KK, et al. Revised IAP growth charts for height, weight and body mass index for 5- to 18-year-old Indian children. Indian Pediatr 2015; 52:47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laxminarayan R, Chaudhury RR. Antibiotic resistance in India: drivers and opportunities for action. PLoS Med 2016; 13:e1001974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prasad N, Murdoch DR, Reyburn H, Crump JA. Etiology of severe febrile illness in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0127962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joshi R, Colford JM, Jr, Reingold AL, Kalantri S. Nonmalarial acute undifferentiated fever in a rural hospital in central India: diagnostic uncertainty and overtreatment with antimalarial agents. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 78:393–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kasper MR, Blair PJ, Touch S, et al. Infectious etiologies of acute febrile illness among patients seeking health care in south-central Cambodia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2012; 86:246–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuchuloria T, Imnadze P, Mamuchishvili N, et al. Hospital-based surveillance for infectious etiologies among patients with acute febrile illness in Georgia, 2008–2011. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2016; 94:236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayxay M, Castonguay-Vanier J, Chansamouth V, et al. Causes of non-malarial fever in Laos: a prospective study. Lancet Glob Health 2013; 1:e46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jean SS, Coombs G, Ling T, et al. Epidemiology and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of pathogens causing urinary tract infections in the Asia-Pacific region: Results from the Study for Monitoring Antimicrobial Resistance Trends (SMART), 2010–2013. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016; 47:328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gagliotti C, Balode A, Baquero F, et al. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus: bad news and good news from the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net, formerly EARSS), 2002 to 2009. Euro Surveill 2011; 16:pii: 19819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS. Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008–2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 73:354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akiba M, Sekizuka T, Yamashita A, et al. Distribution and relationships of antimicrobial resistance determinants among extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant or carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from rivers and sewage treatment plants in India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:2972–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Datta S, Wattal C, Goel N, Oberoi JK, Raveendran R, Prasad KJ. A ten year analysis of multi-drug resistant blood stream infections caused by Escherichia coli & Klebsiella pneumoniae in a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Med Res 2012; 135:907–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holloway K, Mathai E, Sorensen T, Gray T. Community-based surveillance of antimicrobial use and resistance in resources-constrained settings: report on five pilot projects. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Center for Disease Dynamics Economics & Policy. Resistance maps https://resistancemap.cddep.org/AntibioticResistance.php Accessed 5 January 2017.

- 29. National Centre for Disease Control. National treatment guidelines for antimicrobial use in infectious diseases. New Delhi, India: Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. ; Pneumonia Guidelines Working Group Guidelines for diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: joint ICS/NCCP(I) recommendations. Lung India 2012; 29:S27–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alvarez-Uria G, Reddy R. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rural area of India: is MRSA replacing methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in the community? ISRN Dermatol 2012; 2012:248951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goud R, Gupta S, Neogi U, et al. Community prevalence of methicillin and vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in and around Bangalore, southern India. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2011; 44:309–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Field N, Cohen T, Struelens MJ, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Molecular Epidemiology for Infectious Diseases (STROME-ID): an extension of the STROBE statement. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Curcio D. Multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections: are you ready for the challenge? Curr Clin Pharmacol 2014; 9:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dik JW, Vemer P, Friedrich AW, et al. Financial evaluations of antibiotic stewardship programs-a systematic review. Front Microbiol 2015; 6:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:159–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raman G, Avendano E, Berger S, Menon V. Appropriate initial antibiotic therapy in hospitalized patients with gram-negative infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tamma PD, Holmes A, Ashley ED. Antimicrobial stewardship: another focus for patient safety? Curr Opin Infect Dis 2014; 27:348–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schuts EC, Hulscher ME, Mouton JW, et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:847–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bonomo RA, Szabo D. Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:S49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tenover FC. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am J Infect Control 2006; 34:S3–10; discussion S64–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marquet K, Liesenborgs A, Bergs J, Vleugels A, Claes N. Incidence and outcome of inappropriate in-hospital empiric antibiotics for severe infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2015; 19:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crump JA, Ramadhani HO, Morrissey AB, et al. Invasive bacterial and fungal infections among hospitalized HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults and adolescents in northern Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.