Analysis of the genus Moricandia, which contains C3 and C3–C4 intermediate plants, reveals potential environmental and anatomical constraints to the evolution of C4 photosynthesis.

Keywords: Bundle sheath, C3–C4 intermediacy, C4 photosynthesis, evolution, glycine decarboxylase, Moricandia

Abstract

Evolution of C4 photosynthesis is not distributed evenly in the plant kingdom. Particularly interesting is the situation in the Brassicaceae, because the family contains no C4 species, but several C3–C4 intermediates, mainly in the genus Moricandia. Investigation of leaf anatomy, gas exchange parameters, the metabolome, and the transcriptome of two C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia species, M. arvensis and M. suffruticosa, and their close C3 relative M. moricandioides enabled us to unravel the specific C3–C4 characteristics in these Moricandia lines. Reduced CO2 compensation points in these lines were accompanied by anatomical adjustments, such as centripetal concentration of organelles in the bundle sheath, and metabolic adjustments, such as the balancing of C and N metabolism between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells by multiple pathways. Evolution from C3 to C3–C4 intermediacy was probably facilitated first by loss of one copy of the glycine decarboxylase P-protein, followed by dominant activity of a bundle sheath-specific element in its promoter. In contrast to recent models, installation of the C3–C4 pathway was not accompanied by enhanced activity of the C4 cycle. Our results indicate that metabolic limitations connected to N metabolism or anatomical limitations connected to vein density could have constrained evolution of C4 in Moricandia.

Introduction

C4 plants evolved in warm, open, and often arid regions, where the C4 concentrating mechanism leads to enhanced photosynthetic carbon fixation efficiency (Sage, 2004). In most C4 species, this is achieved by upstream CO2 fixation through phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC) in the mesophyll (MS) and transport of the synthesised C4 metabolites to the bundle sheath (BS) cells (Hatch, 1987). Decarboxylation of C4 metabolites in the BS cells increases CO2 concentration around Ribulose-1,5 bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), thus promoting the carboxylase reaction while reducing photorespiration (Hatch and Slack, 1970; Bowes et al., 1971; Hatch, 1987). Division of photosynthetic biochemistry between two different cell types requires anatomical adaptation including high vein density, reduction of MS tissue, and enlarged, chloroplast-rich BS cells (Dengler et al., 1994; McKown and Dengler, 2007; Christin et al., 2013). Despite its complexity, the C4 trait evolved independently more than 60 times in flowering plants (Sage et al., 2012; Sage, 2016). Soon after the discovery of C4 photosynthesis, it became apparent that transition from C3 to C4 photosynthesis could not have been realised in one giant step, but more likely evolved via a series of transitory states (Kennedy and Laetsch, 1974). Potential C3–C4 intermediates were identified by their CO2 compensation point, which lay between the values of C3 and C4 species, as well as some C4-like anatomical features in the BS cells (Kennedy and Laetsch, 1974; Krenzer et al., 1975). The Brassicaceae species Moricandia arvensis was among the first species classified as a potential C3–C4 intermediate (Krenzer et al., 1975).

The genus Moricandia consists of eight accepted species (www.theplantlist.org), all originating from Mediterranean or Saharo-Sindian areas (Tahir and Watts, 2010). Based on CO2 compensation points, Moricandia includes C3 species (M. moricandioides, M. foetida, and M. foleyi) as well as C3–C4 intermediates (M. arvensis, M. suffruticosa, M. nitens, M. spinosa, and M. sinaica; Brown and Hattersley, 1989; Apel et al., 1997). Besides a low CO2 compensation point, the C3–C4 candidates exhibit lower sensitivity to O2 (Holaday et al., 1982) and high incorporation of 14C into glycine and serine (Holaday and Chollet, 1983; Hunt et al., 1987). The BS area per cell profile is increased as well as the number of chloroplasts, mitochondria, and peroxisomes in the BS (Holaday and Chollet, 1983; Hunt et al., 1987). In contrast to C4 species, these potential intermediates possess a C3-like δ13C signature, C3-like Rubisco kinetics (Bauwe and Apel, 1979; Holbrook et al., 1985), and low activities of typical C4 enzymes such as PEPC, pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK), NADP malic enzyme (NADP-ME), NAD-ME, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) (Holaday et al., 1981; Holaday and Chollet, 1983).

Rawsthorne and colleagues showed that the P-subunit of the glycine decarboxylase multi-enzyme system (GLDP) is exclusively localised to the BS of the leaf of M. arvensis (Rawsthorne et al., 1988a, b; Rylott et al., 1998), while all other enzymes of the photorespiratory or photosynthetic pathways, such as the L, H, and T subunits of GLD, serine hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT), glycolate oxidase (GOX), and Rubisco, are found in MS as well as BS tissues (Rawsthorne et al., 1988b, Morgan et al., 1993). These findings led to the first experimentally verified model of photosynthesis in C3–C4 intermediates (Rawsthorne, 1992). The interruption of the photorespiratory cycle in the MS caused by the absence of the functioning GLD/SHMT complex leads to an accumulation of glycine and its diffusion to the BS cells. There, its decarboxylation creates a local CO2 enrichment, thus increasing the carboxylation activity of Rubisco in the BS and therefore reducing the CO2 compensation point of the leaf (Rawsthorne, 1992). This process is also named the glycine shuttle, photorespiratory CO2 pump, or C2 photosynthesis (Sage et al., 2014).

Species with C3–C4 intermediate characteristics have been identified in diverse groups of plants (Krenzer et al., 1975; Rajendrudu et al., 1986; Moore et al., 1987; Hylton et al., 1988; Apel et al., 1997; Muhaidat et al., 2011; Sage et al., 2011b; Wen and Zhang, 2015; Khoshravesh et al., 2016). Phylogenetic studies have shown that many of these C3–C4 plants are closely related to C4 siblings, and it is therefore likely that intermediates served as transitory states on the evolutionary path from C3 to C4 (McKown et al., 2005; Christin et al., 2011a; Fisher et al., 2015; Lyu et al., 2015). The possibility that C3–C4 intermediates bridge the evolutionary gap between C3 and C4 states has also recently been supported by different computational modelling approaches (Heckmann et al., 2013; Williams et al., 2013; Mallmann et al., 2014; Brautigam and Gowik, 2016). Experimental as well as computational models predict that under favourable genetic and anatomic pre-conditions, the shift of GLD to the BS is a decisive step for installation of the glycine shuttle and the transition from C3 to C3–C4 photosynthesis. Because the GLD/SHMT reaction in the BS releases not only CO2 but also NH3, rebalancing of the N metabolism between the two cell types is required (Mallmann et al., 2014). For re-balancing of N metabolism, the current model suggests additional metabolite shuttles, e.g. glutamate–2-oxoglutarate, alanine–pyruvate, and aspartate–malate. Parts of these shuttles and the associated biochemical enzymes also play an important role in C4 photosynthesis. Existing C4 enzymes and transporters can create a primordial C4 cycle in the C3–C4 background on which selection can act as long as selective pressure for efficient C assimilation persists (Aubry et al., 2011; Mallmann et al., 2014; Brautigam and Gowik, 2016). In essence, altered GLD localisation is predicted to initiate a smooth path to C4 (Heckmann et al., 2013; Brautigam and Gowik, 2016; Schluter and Weber, 2016). In support of this model, over 90% of plant lineages with C3–C4 intermediates also contain C4 species (Mallmann et al., 2014).

The model, however, fails to explain the presence of evolutionary stable C3–C4 intermediates. The situation in the Brassicaceae is therefore particularly interesting; to date no sensu stricto C4 species have been identified in this family, but it contains multiple lines of C3–C4 intermediates, including members of the genus Moricandia (Hylton et al., 1988), Diplotaxis tenuifolia (Apel et al., 1997; Ueno et al., 2006), and Brassica gravinae (Ueno, 2011). In this current study, the C3–C4 metabolism in the genus Moricandia was investigated in more detail by simultaneous analyses of phylogeny, leaf anatomy, gas exchange, and metabolite and transcript patterns in closely related C3 (M. moricandioides) and C3–C4 species (M. arvensis line MOR1 and M. suffruticosa). The data were used for testing hypotheses related to C4 evolution or lack thereof: (i) phylogenetic patterns of GLDP explain the evolution of intermediacy in just one specific branch of the Brassicaceae; (ii) metabolic differences between C3 and intermediate species relate to the N-shuttle; and (iii) differences with the genus Flaveria, which evolved full C4, indicate where Moricandia species might be restricted in evolution towards C4.

Material and methods

Plant cultivation

Seeds for different Moricandia lines were obtained from botanic gardens and seed collections (Moricandia moricandioides, 04-0393-10-00 from Osnabrück Botanic Gardens; M. arvensis, line 12-0020-10-00 from Osnabrück Botanic Gardens, lines 0119708, 0000321, 0084187 from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, lines MOR1 and MOR3 from IPK Gatersleben; M. suffruticosa, line 0105433 from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew; M. nitens, 0209858 from the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew). Seeds were vapour-sterilised by incubation in a desiccator together with a freshly prepared mix of 100 ml 13% Na-hypochloride with 3 ml of 37% HCl for 2 h. The sterilised seeds were then germinated on plates containing 0.22% (w/v) Murashige Skoog medium, 50 mM MES pH 5.7 and 0.8% (w/v) Agar. After about a week, seedlings were transferred to pots containing a mixture of sand and soil (BP substrate, Klasmann & Deilmann GmbH, Germany) at a ratio of 1:2. In the first experiment, testing all the Moricandia lines, plants were grown in a greenhouse (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf) in September 2013, where they received natural light ranging from 300 and 600 µmol s−1 m−2. For our more detailed studies of C3–C4 intermediate metabolism in Moricandia, we chose one species from each Moricandia C3–C4 subgroup presented in Fig. 1A (M. suffruticosa from group I and M. arvensis line MOR1 from group II) and compared them to their C3 relative M. moricandioides. For all following experiments, plants were cultivated in a climate chamber (CLF Mobilux Growbanks, Wertingen, Germany) under 12-h day conditions with 23/20 °C day/night temperatures. The plants were exposed to ambient CO2 concentrations and irradiance at plant level was ~200 µmol s−1 m−2. All experiments were conducted before the transition to the reproductive state. Mature leaf material was harvested from M. moricandioides, M. arvensis (line MOR1), and M. suffruticosa ~2 h after the start of the light period by flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen. The material was homogenised into a fine powder by grinding in liquid nitrogen. The material was stored at –80 °C and used for analysis of elements, metabolites, transcripts, and proteins.

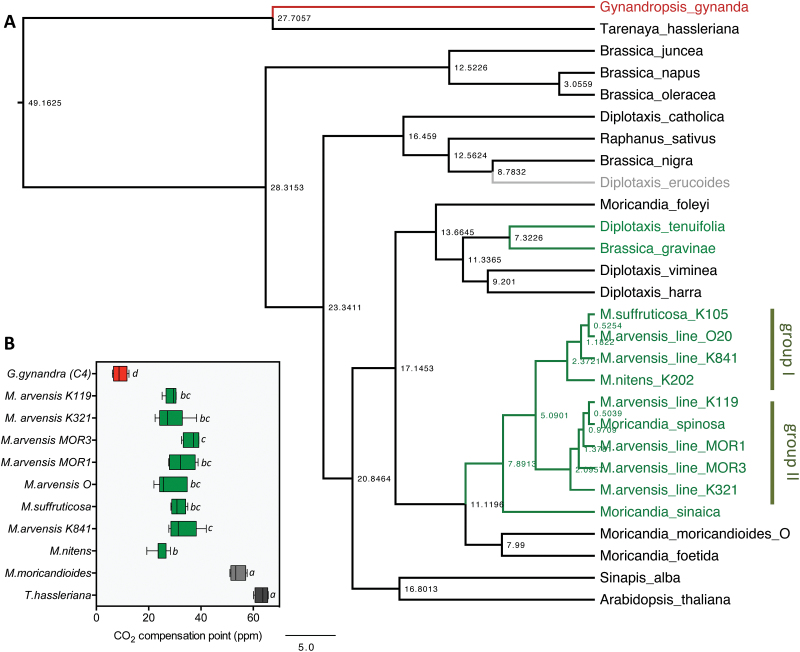

Fig. 1.

C3-C4 intermediate species in the Brassicaceae. (A) Time-calibrated phylogeny of the Brassicaceae species selected for this study. The Moricandia species build one branch of the tree with an early separation of the C3 species M. moricandioides and M. foetida, and the C3–C4 intermediate species M. suffruticosa, M spinosa, M. sinaica, M. nitens, and different M. arvensis lines. Additional independently established C3–C4 intermediate species are Diplotaxis tenuifolia and Brassica gravinae. The closest C4 relative G. gynandra belongs to the Cleomaceae. C3 species are in black; C3–C4 intermediate species in green, with gray for the potential intermediate D. erucoides; C4 species in red. The scale bar is 5 Ma. (B) CO2 compensation points determined from A-Ci curves in C3 and C3–C4Moricandia lines compared with C3 and C4 species from the Cleomaceae. Significant differences were determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD multiple comparison test with alpha ≤0.01.

Phylogeny

Relationships between Moricandia species and their closest relatives were determined using sequences from the ITS nuclear region. DNA was extracted from all the Moricandia lines available in our study, Diplotaxis tenuifolia (line ‘Wilde Rauke’, origin: N.L. Chrestensen Erfurter Samen-und Pflanzenzucht GmbH), and D. viminea (line GB.31066, origin: Rijk Zwaan Distribution B.V., Netherlands). The ITS sequences were amplified and sequenced using the primers ITS1 (O’Kane et al., 1996) and ITS4 (White et al., 1990). Additional ITS sequences were retrieved from the NCBI database (see Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). The sequences were aligned with Muscle (Edgar, 2004), and the alignment was used to infer a time-calibrated phylogeny following a relaxed molecular clock approach, as implemented in Beast (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). The analysis was run for 10 000 000 generations, sampling a tree every 1000 generations under a GTR+G+I substitution model, a log-normal relaxed clock, and a Yule speciation prior. The tree was rooted by forcing the monophyly of both the outgroup (the two ‘Cleome’ species) and the ingroup (Brassicaceae). The tree was calibrated by setting the age of the crown of Brassicaceae with a normal distribution with a mean of 29.3 Ma and a standard deviation of 3.0, based on estimates from markers across nuclear genomes (Christin et al., 2014). The convergence of the analysis and adequacy of the burn-in period were verified using Tracer (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007). Medians of node ages for tree samples after a burn-in period of 1 000 000 generations were mapped on the maximum-credibility tree using Treeannotator (Drummond and Rambaut, 2007).

GLDP-specific mRNA sequences were retrieved from online databases (see Supplementary Table S2). GLDP-specific coding sequences for Moricandia and Diplotaxis lines were obtained from the assembly of next-generation sequencing reads produced in our own lab (see below). The phylogenetic tree was constructed with the help of the Phylogeny.fr webtool (http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr) in the default mode consisting of alignment by Muscle, G-block building, maximum-likelihood tree generation by PhyML, and visualisation by TreeDyn.

Plant anatomy

Vein density measurements were done on the top third of fully grown rosette leaves. The leaf material was cleared in an acetic acid:ethanol mix (1:3) overnight followed by staining of cell walls in 5% safranin O in ethanol, and de-staining in 70% ethanol. Pictures were taken using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope equipped with a ProgRes MF camera (Jenoptik, Jena, Germany), at 4× magnification. At least six leaves were analysed for vein density per line, always with five pictures measured and averaged per leaf using ImageJ open software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

For histological and ultrastructural analysis 2-mm2 sections from mature rosette leaves were used for combined conventional and microwave-proceeded fixation, dehydration, and resin embedding in a PELCO BioWave®34700-230 (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding CA, USA) as described in Supplementary Table S3. Semi-thin sections with a thickness of approximately 2.5 µm were mounted on slides and stained for 2 min with 1 % methylene blue / 1% Azur II in 1% aqueous borax at 60 °C prior to light microscopical examination in a Zeiss Axio Imager M2 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). Ultra-thin sections with a thickness of approximately 70 nm were cut with a diamond knife, transferred onto TEM-grids and contrasted in a LEICA EM STAIN (Leica Microsystems, Vienna, Austria) with uranyl acetate and Reynolds’ lead citrate prior to analysis using a Tecnai Sphera G2 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands) at 120 kV.

Photosynthetic gas exchange

Mature rosette leaves were used for gas exchange measurements with a LICOR 6400XT (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, USA). The settings were a flow of 300 µmol s−1, light of 1500 µmol m−2 s−1, leaf temperature of 25 °C, and the vapour pressure deficit was kept below 1.5 kPa. Initial analysis of the Moricandia lines and comparison with the related C3 plants Brassica oleraceae and Tarenaya hassleriana, the C3–C4 intermediate Diplotaxis tenuifolia, and the C4 plant Gynandropsis gynandra were done with A-Ci curves, with measurments at 400, 50 100, 200, 400, 800, 1200, and 1800 ppm CO2. Significance of the differences in the CO2 compensation points between lines was tested using a one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test.

More detailed A-Ci curves were measured on the selected species M. moricandioides, M. arvensis MOR1, and M. suffruticosa. After acclimation, an A-Ci curve was determined starting at a CO2 concentration (Ca) of 400 ppm, then going down to 20 ppm in nine steps, then going back to 400 ppm and raising the CO2 concentration stepwise up to 1800 ppm. Measurements at the lowest six CO2 concentrations were used to extract the CO2 compensation point and the initial slope of the graph corresponding to the carboxylation efficiency. Maximal assimilation was determined at CO2 concentrations of 1600 to 1800 ppm. At least six plants were measured per line, and statistical significance between values for the different species was evaluated using Student’s t-test.

Metabolite and element analysis

The homogenized leaf material was extracted for metabolite analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) according to Fiehn et al. (2000) using a 7200 GC-QTOF (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). Data analysis was conducted with the Mass Hunter Software (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). For relative quantification, all metabolite peak areas were normalized to the peak area of an internal standard of ribitol added prior to extraction. The same homogenised leaf material was used for determination of δ13C and CN ratios. After lyophilisation, the material was analysed using an Isoprime 100 isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled to an ISOTOPE cube elemental analyzer (both from Elementar, Hanau, Germany) according to Gowik et al. (2011). Measurements were always done on ten biological replicates. Statistical significance was analysed using Student’s t-test.

Transcript analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the homogenized leaf material using the GeneMatrix Universal RNA purification kit (Roboklon GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The RNA was treated with DNase for a few seconds only and quality controlled on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). Subsequently, mRNA purification and adapter ligation was performed with the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, USA) using 1 μg of total RNA. After a second quality control on the Bioanalyzer, samples were sent to Beckmann Coulters Genomics (Danvers, MA, USA) and sequenced on a HiSeq2500 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) as single-end 100-bp reads. Three to four biological replicates were used per Moricandia species with between 13 and 17 million reads per sample. The reads were aligned to a minimal set of coding sequences of the TAIR 10 release of the Arabidopsis genome (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) using BLAT (Kent, 2002) in protein space. The best BLAT hit for each read was determined by (1) the lowest e-value and (2) the highest bit score (Brautigam et al., 2011). Raw read counts were transformed to reads per million (rpm) to normalize for the number of reads available at each sampling stage. Cross-species mapping takes advantage of the completeness and annotation of the Arabidopsis genome. In all samples, 80 to 86% of reads mapped to the reference genome. Comparison of the transcript pattern between species was performed with the edgeR tool (Robinson et al., 2010) in R (www.R-project.org) using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery test with a cut-off at false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.01 for significant differences. The agriGO webtool was employed for gene ontology (GO) term analysis (Du et al., 2010). The transcriptome data was deposited at the GEO repository (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE87343.

For construction of the specific Moricandia transcript assemblies, one sample per line was sequenced as pair-end 150-bp reads on an Illumina HiSeq2000 platform at the BMFZ (Biologisch-Medizinisches Forschungszentrum) of the Heinrich Heine University (Düsseldorf, Germany). The resulting reads were trimmed using the trimmomatic tool (Bolger et al., 2014) followed by assembly using Trinity (Haas et al., 2013), which yielded between 68 000 and 91 000 contigs. Sequences for transcripts from D. tenuifolia, D. viminea, and D. muralis were obtained following the same protocol.

PEPC activity

Total soluble proteins were extracted from the homogenised leaf material in 50 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton-X-100, 0.1% ß-mercaptoethanol. For the PEPC assay, 20 µl of the extract were mixed with assay buffer consisting of 100 mM Tricine-KOH pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM KHCO3, 0.2 mM NADH, 5 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 2 U ml−1 malate dehydrogenase in a microtiter plate (Ashton et al., 1990). The reaction was started after addition of phosphoenolpyruvate to a final concentration of 5 mM in the assay. Absorbance at 340 nm was measured with a Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). Protein content of the solutions was determined with the Bradford assay (Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay kit, BioRad). The ratio between fresh and dry weight of the leaf material was determined by weighing a second mature leaf from the same plants before and after drying it at 70 °C overnight.

Results

Occurrence of C3–C4 intermediates in the Brassicaceae

The phylogenetic relationships between all the Moricandia accessions available in our study were investigated by sequencing their ITS region and in comparison with data available in the NCBI database (Fig. 1A). We aimed at testing whether the C3–C4 character evolved independently or in one single event in different Moricandia lines. With the exception of M. foleyi, all Moricandia species formed a monophyletic group in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1A). Within this clade, a C3 group (M. moricandioides, M. foetida) was sister to the C3–C4 intermediate species (M. arvensis, M. suffruticosa, M. nitens, M. sinaica, M. spinosa; Fig. 1A), indicating that the evolution of the C3–C4 intermediate character is most-parsimoniously explained by a single event in the Moricandia genus. Intermediates with smaller, more ellipse-shaped leaves (group I, Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S1) formed a monophyletic group, while the intermediates with mainly longer petioles formed a paraphyletic clade (group II). Lines taxonomically assigned to M. arvensis could be found within both groups.

Besides the Moricandia C3–C4 species, very similar features, such as significantly reduced CO2 compensation points, occur in Diplotaxis tenuifolia and Brassica gravinae (Apel et al., 1997; Ueno, 2003, 2011). The development of C3–C4 intermediacy in these species was clearly independent from the events in Moricandia (Fig. 1A). Phylogenetic trees of the Brassicaceae with higher species density (Warwick and Sauder, 2005; Arias et al., 2014) suggest that these species belong to different branches of the tree and that C3–C4 intermediacy also evolved independently in D. tenuifolia and B. gravinea. In the list of Apel et al. (1997), single measurements of CO2 compensation points in D. muralis and D. erucoides also indicated low CO2 compensation points. Diplotaxis muralis is a hybrid between D. viminea (C3) and D. tenuifolia (C3–C4) and usually closer to C3 in its gas exchange characteristics (Ueno et al., 2006), but detailed studies are lacking for D. erucoides. It is also remarkable that C3–C4 intermediates were only found in the Oleracea group of the Brassciceae tribe, in the lineage II Brassicaceae (Apel et al., 1997; Warwick and Sauder, 2005; Arias et al., 2014), but no C3–C4 intermediates have so far been identified in any other subgroup of this large family.

Physiological features allow differentiation of C3 and C3–C4Moricandia lines

Many details of the C3–C4 intermediate photosynthesis character were investigated in the 1980s and 1990s at the University of Nebraska (see Holaday et al., 1981, 1982; Holaday and Chollet, 1983), in Gatersleben in Germany (see Bauwe and Apel, 1979; Apel et al., 1997), and at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, UK (see Rawsthorne et al., 1988a, b; Rylott et al., 1998). Since the stock seed material from these initial analyses could no longer be obtained, CO2 compensation points in genotyped greenhouse-grown lines were characterized (Fig. 1B) and compared with data from the C3 plant T. hassleriana and the C4 plant G. gynandra from the neighbouring Cleomaceae family. The measurements of the CO2 compensation points clearly allowed classification of the tested lines as a C3, C3–C4, or C4 species (Fig. 1B). All C3–C4 intermediate lines had CO2 compensation points that were significantly lower than in the C3 species, but also significantly higher than in the C4. On the other hand, no significant differences could be observed among the C3–C4 intermediate lines.

The selected accessions M. moricandioides, M. arvensis MOR1, and M. suffruticosa were then grown under controlled environmental conditions in a climate chamber. Under these conditions, the differences in the CO2 compensation point of the C3 and C3–C4Moricandia species were even more pronounced (Fig. 2A, B). A closer inspection of the shape of A-Ci curves showed that, despite the low CO2 compensation point, the curve of the intermediates looked much more similar to the C3 curve than the one of the C4 species G. gynandra, which had a very steep initial ΔA/ΔCi slope of 0.557 (Fig. 2A). The initial slope of the A-Ci curve is connected to the carboxylation efficiency in the photosynthetic system, the PEPC efficiency in C4, and the Rubisco carboxylation efficiency in C3 (von Caemmerer, 2000). A comparison of the A-Ci curves in the C3 and C3–C4Moricandias showed that the initial slope was actually steeper in the C3 species than in the C3–C4 intermediate lines (Fig. 2A, C).

Fig. 2.

Physiological features in the C3 species M. moricandioides, and the C3–C4 intermediate species M. suffruticosa and M. arvensis line MOR1. (A) Representative examples of A-Ci curves from M. moricandioides, M. suffruticosa, and M. arvensis line MOR1 in comparison with the curve from the C4 species G. gynandra. (B) CO2 compensation points; (C) initial A-Ci slope; (D) assimilation rate under ambient conditions with ca of 400 ppm; (E) δ13C signature of leaf material; (F) protein content per plant dry weight; (G) PEPC activity; (H) vein density in the top part of mature leaves. All box-whisker plots show data summarised from 8–10 biological replicates. The asterisks indicate significant differences of the C3–C4 intermediate species in comparison with the C3 species M. moricandioides, as determined by a t-test (P≤0.01). Mmori, M. moricandioides; Marv, M. arvensis line MOR1; Msuff, M. suffruticosa. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

The assimilation at ambient CO2 was lower in the C3–C4 intermediate species than in the C3 species (Fig. 2D). Differences in conductance were not responsible for this variation, and the maximal CO2 assimilation at high CO2 reached similar levels in all species tested (see Supplementary Table S4). In addition, measurements of PEPC activity in extracts from mature leaves indicated that PEPC did not play a major role in the primary fixation of CO2 in C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia species (Fig. 2G). No significant differences could be observed in the carbon isotope ratio of the C3 and C3–C4 intermediate species (Fig. 2E). The protein content per total dry weight tended to be lower in the intermediates as compared to the related C3 species M. moricandioides; however, these results were only significant for one C3–C4 line, M. arvensis (Fig. 2F).

Differences in CO2 compensation points are connected to anatomical changes

The development of C3–C4 intermediate physiology relies on functional specification of metabolism in the MS and BS cells and an increase in the metabolite exchange between the two cell types. Differences among photosynthetic types were therefore expected to be closely connected to changes in the anatomy, which were evaluated on a histological and ultrastructural level.

Measurements of vein length per area revealed that the C3–C4Moricandia species had lower or equal vein density when compared to the C3 relative (Fig. 2H). In the top view of cleared leaves, veins of C3–C4 intermediate species appeared thicker than in the C3 species (Fig. 3A–C), probably connected to the large number of chloroplasts, which were centripetally arranged around the veins in the leaf cross-sections (Fig. 3D–I). In-depth ultrastructural analysis showed a high number of mitochondria located predominantly in the cytoplasm between the chloroplasts and the cell wall of adjacent cells of the vascular tissue of C3–C4 plants (Fig. 3J–L). The C3 species M. moricandioides had eight cell layers, while M. suffruticosa and M. arvensis both had one MS cell layer fewer (Supplementary Table S4, Fig. 3D–F). Such a reduction in the MS tissue alone could be responsible for a shift in the leaf cell profile towards a higher proportion of BS cells (McKown and Dengler, 2007).

Fig. 3.

Anatomy of the C3 species M. moricandioides (A, D, G, J), and the C3–C4 intermediate species M.suffruticosa (B, E, H, K) and M.arvensis line MOR1 (C, F, I, L). (A–C) Top view of cleared leaves showing the general vein pattern; (D–F) overview of cross-sections; (G–I) close-up of the arrangement of chloroplasts in the bundle sheath cells; (J–L) transmission electron microscopy of bundle sheath cells with organelles arranged next to the vein cell. Arrow heads indicate vascular bundles. BS, bundle sheath cell; Xy, xylem cell; CC, companion cell.

Specific metabolite pattern in C3–C4 intermediates

The metabolite pattern of the leaves is expected to be influenced by species-specific differences as well as by the photosynthesis type. The overall metabolite patterns in M. moricandioides, M. suffruticosa, and M. arvensis were first assessed by principal component analysis (PCA) (see Supplementary Fig. S2A). In the first principal component (PC1), samples from the C3 species M. moricandioides localised predominantly to the right, next to samples of C3–C4 intermediate species. PC2 mainly separated the two C3–C4 intermediate species. The samples from both C3–C4 intermediates were also characterised by high variation. Three metabolites showed significantly (P≤0.01) different concentrations in all tested comparisons (M. arvensis vs M. moricandioides, M. suffruticosa vs M. moricandioides, and M. suffruticosa vs M. arvensis): maleic acid, serine, and threonine (Supplementary Fig. S2B). To distinguish between C3 and C3–C4 intermediate species, we screened for metabolites that significantly differed between the C3 and the two C3–C4 species, but not between the two intermediates. Among the nine metabolites in this category were alanine, glycine, GABA, gluconic acid, leucine, malate, malonic acid, and valine (Supplementary Fig. S2B, Supplementary Table S4).

The predicted N shuttle metabolites (Mallmann et al., 2014), glutamate, alanine, and malate, had higher concentrations in both intermediate Moricandia lines. Aspartate was only increased in M. suffruticosa (Fig. 4). Glycolate and glycerate are part of the photorespiratory pathway, but no significant differences in the concentration of these two metabolites were detected in leaves of the C3 and C3–C4Moricandia species (Fig. 4), confirming that these metabolites do not play a major role in coordination of metabolism between MS and BS cells.

Fig. 4.

Selected metabolites in the C3 species M. moricandioides, and the C3–C4 intermediate species M. suffruticosa and M. arvensis line MOR1. The box-whisker plots represent summaries of 10–12 biological replicates. The asterisks indicate significant differences between the C3–C4 and the C3 species as determined by a t-test (P≤0.01). Mmori, M. moricandioides; Marv, M. arvensis line MOR1; Msuff, M. suffruticosa. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

Transcript patterns do not show a strong specific C3–C4 signature

Next-generation sequencing allows an analysis and comparison of the transcriptomes of species for which no reference genome is available by mapping the reads against the minimal transcriptome of Arabidopsis thaliana (Brautigam et al., 2011). In all Moricandia samples, between 79% and 86% reads were mapped, which is higher than in previous work with Asterales species (Gowik et al., 2011). PCA showed that the transcript pattern was most prominently influenced by the species (see Supplementary Fig. S3A). PC1 clearly separated samples from M. moricandioides, M. arvensis, and M. suffruticosa, while PC2 only separated M. moricandioides and M. arvensis from M. suffruticosa (Supplementary Fig. S3A). Subsequent PCs were already influenced by replicate-specific differences. An influence of the photosynthesis type was not detected in the first three PCs (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

The abundance of 1671 transcripts was significantly different in the C3 and the C3–C4 intermediate leaves, but not between the two intermediates. All of these had changed in both C3–C4 intermediate species to the same direction: 797 were commonly enhanced in C3–C4 while 874 were commonly reduced in C3–C4 (Supplementary Fig. S3C, Supplementary Table S5). GO term analysis of both groups of transcripts revealed quite diverse categories. Only two GO terms were enriched among transcripts enhanced in C3–C4, while 21 process GO-terms were enriched in transcripts reduced in C3–C4. The latter included high-level terms such as cellular compound, nitrogen metabolism, and carbohydrate metabolism. The cellular compartment mainly affected by transcript reduction in C3–C4 intermediates appeared to be the chloroplast (see Supplementary Table S6).

The metabolism in C3–C4 intermediate leaves is predicted to differ from C3 leaves mainly with respect to cellular distribution of photorespiratory processes and subsequent re-adjustment of C and N balance by metabolite shuttle mechanisms (Mallmann et al., 2014). Transcripts predicted to be involved in all these processes were therefore studied in more detail. No changes were observed for transcripts encoding components of the photorespiratory pathway, in particular the GLDP protein, which is only present in the BS cell of C3–C4 intermediates (Fig. 5). Not all transcripts of the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle did show significant differences between C3 and C3–C4 species. It was, however, noticeable that almost all transcripts tended to be reduced in the C3–C4 intermediate species when compared to C3 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Transcriptional changes in selected pathways. The heat maps indicate the log2-fold changes in transcript level between C3–C4 species M. arvensis line MOR1 (left column) and M. suffruticosa (right column) and the C3 species M. moricandioides. Blue indicates reduced transcript abundance in C3–C4, red indicates enhanced transcript abundance in C3–C4.

Expression of transcripts belonging to the photorespiratory and CBB pathways is generally lower in C4 than C3 species (Brautigam et al., 2011). The evolutionary trajectory of pathway expression from C3 via C3–C4 to C4 metabolism can be followed in Flaveria species and compared to the results from Moricandia. No large changes in the average transcript abundance of the photorespiratory pathway were detected in the intermediate Flaveria species. The abundance of photorespiratory transcripts decreased only in the C4-like F. brownii and then even more in the C4 species (Fig. 6). The same pattern was also observed for the CBB cycle. A decrease of CBB cycle transcripts in intermediates without increased C4 cycle activity, as we found in the two investigated Moricandia species, was not observed in Flaveria (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the changes in transcript levels of the Moricandia species and Flaveria species with different degrees of C4 features. The graphs show the relative amount (z-score normalised data of mean rpm values) from transcripts belonging to the selected pathways. The general trend in the transcription pattern of a pathway is indicated in red as the median of the individual transcripts values. Species abbreviations are: Mmori, M. moricandioides; Marv, M. arvensis; Msuff, M. suffruticosa; Fpri, F. pringlei; Frob, F. robusta; Fchl, F. chloraefolia; Fpub, F. pubescence; Fano, F. anomala; Fram, F. ramosissima; Fbro, F. brownii; Fbid, F. bidentis; Ftri, F. trinervia.

Transcripts encoding enzymes with potential functions in the metabolite shuttles between MS and BS cells were inspected in detail. Only the aspartate aminotransferase (AspAT) encoding genes were enhanced in both intermediates compared to the C3 species (Fig. 5). Furthermore, transcripts that could potentially be recruited into a C4 cycle were tested for their pattern (Fig. 5). In Flaveria, basic C3–C4 intermediates were characterised by increases in alanine aminotransferase (AlaAT) and NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) transcripts, in the evolutionary series this was followed by increases in PEPC transcripts, which were enhanced in all but one of the basic Flaveria intermediates (F. chloraefolia; Fig. 6). In C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia species, AlaAT transcripts were not enhanced, and only slight increases in NADP-ME transcripts were observed (Fig. 5). Another potential C4 decarboxylating enzyme, PEPCK, showed enhanced transcript abundance in the C3–C4Moricandia intermediates (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S7). The same was true for the PPDK transcripts. Two PEPC transcripts with C3-like characteristics (Paulus et al., 2013) were found in noticeable amounts in Moricandia leaves. The higher-abundant form was actually reduced compared to the C3 transcriptome, and only the lower-abundant form was enhanced in the intermediates (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S7).

The GLD/SHMT reaction in the BS also produces NADH and this may require adjustments of the redox balance in the cells. Strong increases were observed for transcripts encoding alternative oxidases (AOX) in the C3–C4 intermediates. The same tendency was found for the uncoupling protein (UCP) and the dicarboxylate transporter DIC2 (see Supplementary Table S7). A NADH dehydrogenase transcript on the other hand was reduced in the C3–C4 leaves (Fig. 5). Increases in AOX and UCP transcripts were not unique to Moricandia, but were also observed in the C3–C4Flaveria intermediates. In the C4-like and C4Flaveria species, the AOX and UCP transcripts decreased again compared to the C3 plant. Hence the increase in AOX transcript abundance was a common feature in C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia and Flaveria species (Figs 5 and 6).

Moricandia species possess only a single copy of the GLDP gene

The number of GLDP copies and their phylogenetic relationship was investigated in the Brassicaceae. Only species where full genome information was available were considered for the comparison. Arabidopsis thaliana has two copies of the gene, AtGLDP1 and AtGLDP2 (Engel et al., 2007). Comparison with other Brassicaceae revealed that other species from the Brassicaceae lineage I (Arabidopsis lyrata, Camalina sativa, Capsella rubella) as well as species from the extended lineage II (Eutrema salsugineum, Thellungiella halophila) also possess transcripts with high similarity to both Arabidopsis genes (Fig. 7). From Arabis alpina only the AtGLDP2-like gene was identified. In the Brassica species B. rapa, B. oleracea, and B. napus on the other hand, only AtGLDP1-like copies were found (Fig. 7). Transcriptomes from mature leaves of M. moricandioides, M. suffruticosa, M. arvensis, Dipoltaxis tenuifolia, D. viminea, and D. muralis also assembled only copies with high similarity to the AtGLDP1 gene. In all these species, GLDP was represented by one unique transcript. Two transcripts were assembled only in D. muralis, one with a high similarity to the sequence of D. tenuifolia and the other one with high similarity to the D. viminea sequence. Since D. muralis is a hybrid between these two species, this was expected and underlines the successful assembly of the GLDP gene sequences in our study. An assembly of gene sequences from a leaf transcriptome could still miss copies that are simply not expressed at all in the leaves examined. The complete absence of AtGLDP2-like sequences also in the genome of the sequenced Brassica species, however, indicated that the AtGLDP2 copy was absent in the whole Brassiceae subgroup containing Brassica, Moricandia, and Diplotaxis species, most likely by loss at the base of Brassiceae subgroup.

Fig. 7.

Phylogenetic tree of the glycine decarboxylase P-protein (GLDP) coding sequences in selected Brassicaceae. The GLDP copies from Arabidopsis thaliana are highlighted in blue, Moricandia species are in red, and Diplotaxis species are in green. Species abbreviations are: At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Alyt, Arabidopsis lyrata; Aalp, Arabis alpina; Bna, Brassica napus; Bo, B. oleraceae; Bra, B. rapa; Eutsa, Eutrema salsugineum; Thal, Thellungiella halophile; Csat, Camelina sativa; Carub, Capsella rubella; Thass, Tarenaya hassleriana; Mmori, Moricandia moricandioides; Mnit, Moricandia nitens; Marv, Moricandia arvansis line MOR1; Msuff, Moricandia suffruticosa; Dvim, Diplotaxis viminea; Dten, Diplotaxis tenuifolia; Dmur, Diplotaxis muralis). Branch support is determined by an approximate likelihood ratio test.

Discussion

Evolution from C3 to C3–C4 was promoted by lack of a second GLDP copy in the Brassiceae

Evolution of C4 photosynthesis is not equally distributed across the plant kingdom, being frequent in some groups but completely absent from many others with similar growth forms (Sage et al., 2011a; Sage, 2016). In the Brassicaceae we find no true C4, but possibly three independent C3–C4 lines (Moricandia, Diplotaxis tenuifolia, Brassica gravinae), and all these lines belong to the Oleracea group of the Brassiceae (Warwick and Sauder, 2005; Arias et al., 2014).

The decisive step from C3 to C3–C4 intermediacy is associated with a shift of the activity of photorespiratory GLD from ubiquitous expression to almost exclusive expression in the BS (Heckmann et al., 2013; Khoshravesh et al., 2016). Detailed studies of the promoter sequences of the GLDP in Flaveria have shown that the regulatory elements mediating BS-specific expression were already present in the C3 ancestors (Schulze et al., 2013). Flaveria species possess two copies of the GLDP gene: one is ubiquitously expressed in the leaf tissue (GLDPB), while transcripts of the other one were found exclusively in the BS (GLDPA). The transition from C3 to C3–C4 photosynthesis in Flaveria was then realised via a gradual decrease and finally pseudogenization of the ubiquitously expressed copy and exclusive expression of the BS-specific gene (Schulze et al., 2013).

Arabidopsis thaliana belongs to the lineage I of the Brassicaceae and also possesses two copies of the GLDP gene, AtGLDP1 and AtGLDP2, and both are abundantly expressed in leaf tissue (Engel et al., 2007). Orthologs of the genes were also detected in species from the same lineage and also in the extended lineage II of Brassicaceae. Only in the Brassiceae subgroup, which includes all known C3–C4 Brassicaceae species, was the AtGLDP2-like copy missing (Fig. 7). The step from C3 to C3–C4 photosynthesis in the Brassicaceae was apparently facilitated by loss of the GLDP2 copy. Analysis of the promoter region from the AtGLDP1 gene revealed the presence of an MS (M-box) as well as a BS/vein (V-box) -specific element and these were highly conserved throughout the Brassicaceae family (Adwy et al., 2015). Changes in the M-box of the promoter could therefore easily lead to loss of gene function in the mesophyll, and without a second copy of the gene, BS-specific GLDP expression typical for the C3–C4 species could be realised, driven by the V-box. This scenario is supported by the absence of the M-box but the conserved presence of the V-box in the GLDP promoter of the C3–C4 species Moricandia nitens (Zhang et al., 2004; Adwy et al., 2015). In Flaveria, it has been hypothesised that a gradual decrease of MS GLDP expression might have been crucial for the adjustment of intercellular metabolism (Schulze et al., 2013). It will be interesting to investigate whether single nucleotide changes are sufficient to completely disrupt the function of the Brassicaceae M-box. So despite the differences in the order of events in Flaveria and Moricandia, in both genera BS-specific elements were present in the GLDP promoter sequences of C3 ancestors and the transition from C3 to C3–C4 photosynthesis could be promoted by small changes in the genome.

C3–C4 characteristics are stable in different Moricandia species

Moricandia species had been characterised for their specific physiological, anatomical, and biochemical properties (Bauwe and Apel, 1979; Rawsthorne et al., 1988a, b; Brown and Hattersley, 1989), but direct comparisons of the results from the different laboratories could be problematic because the features investigated might vary among different accessions of the same species (Sayre and Kennedy, 1977). We therefore tested CO2 compensation points and phylogenetic relationships between one C3M. moricandioides line and eight different C3–C4 intermediate lines. In the phylogenetic tree, all C3–C4 intermediates of Moricandia formed a monophyletic clade, indicating that the evolution of C3–C4 photosynthesis probably occurred once, with subsequent speciation (Fig. 1A). The CO2 compensation points of all the C3–C4 lines tested were significantly lower than in C3 relatives and higher than in the C4 species G. gynandra, but the lines did not differ amongst each other (Fig. 1B).

In the C3–C4 accessions M. arvensis line MOR1 and M. suffruticosa, the reduction in CO2 compensation point was closely associated with an increase in organelle number and their centripetal arrangement in the BS cells of the mature leaf (Fig. 3). A very similar picture has been described for the C3–C4 species Moricandia spinosa (Brown and Hattersley, 1989) and M. arvensis (Holaday et al., 1981), as well as C3–C4 species from other plant families (McKown and Dengler, 2007; Muhaidat et al., 2011; Khoshravesh et al., 2016). BS cells in the C3–C4 intermediates are still in direct contact with the intercellular space and CO2 can diffuse in and out of the cell. Therefore, the efficiency of the glycine shuttle and re-fixation of the released CO2 depends on the close arrangement of the mitochondria, where CO2 is released, and the chloroplasts, where the carboxylation reaction of Rubisco can profit from the proximate increase in CO2 concentration.

After establishment of the photorespiratory glycine shuttle, further fitness gains are predicted by support of the glycine shuttle by C4 acids, which serve as carbon backbones for re-assimilation of photorespiratory ammonia (Heckmann et al., 2013; Mallmann et al., 2014). The majority of Flaveria C3–C4 intermediates are characterised by enhanced PEPC activity and a limited C4 cycle (Vogan and Sage, 2011; Mallmann et al., 2014). In C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia species, the PEPC activity was not changed compared to the C3 species (Fig. 2G). Earlier measurements of PEPC activity in M. arvensis showed a slight two-fold increase in comparison to the C3 species M. foetida (Holaday et al., 1981). However, 14C labelling experiments gave no further evidence for a significant contribution of C4 acids to the photosynthetic carbon assimilation (Holaday and Chollet, 1983; Hunt et al., 1987). Values for δ13C, which would indicate a substantial contribution of PEPC to primary CO2 fixation, were also indistinguishable between C3 and C3–C4Moricandia species. In Flaveria, the installation of the glycine shuttle led to implementation of different degrees of the C4 cycle, including true C4 photosynthesis, but in the Moricandia species analysed similar developments were not accompanied by a substantial C4 pathway contribution.

C3–C4 specific metabolism influences metabolite but not transcript patterns in Moricandia

The absence of GLD is thought to induce enhanced glycine concentration in the MS, followed by diffusion of the metabolite to the BS (Rawsthorne and Hylton, 1991). As expected, an increase in the glycine concentration was detectable in total leaf extracts from M. arvensis and M. suffruticosa (Fig. 4). Serine, as the direct product of the GLD/SHMT, reaction is most likely one of the metabolites transported back to the MS cell. Just like glycine, its steady-state pool is typically increased in C3–C4 intermediate leaf extracts and it is characterised by a high turnover rate in the illuminated leaf (Fig. 4; Rawsthorne and Hylton, 1991). The pools of metabolites suggested to maintain N-balance (e.g. glutamate, alanine, malate) were also increased in the C3–C4Moricandia lines when compared to the C3 relative species; only aspartate was enhanced in just one intermediate line. A strong preference for one of the suggested shuttle mechanisms could, however, not be detected. The results tend to suggest that many shuttles contribute to the metabolic balancing between the cells (Fig. 8), and it is very well possible that further metabolites are involved.

Fig. 8.

Model of metabolite shuttle network active between the mesophyll cells (left) and bundle sheath cells (right) of C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia species. The inactivity of the photorespiratory glycine decarboxylating complex in the mesophyll cells leads to glycine accumulation and transport to the bundle sheath. In the mitochondria of bundle sheath cells two molecules of glycine are converted by the GLD/SHMT complex to serine, CO2, NH3, and NADH. In the adjacent chloroplasts the bundle sheath Rubisco is exposed to enhanced CO2 conditions. The imbalance created by parallel release of NH3 requires further adjustment of C and N metabolism that is probably realised by a whole network of reactions, including additional shuttling of amino acids from the bundle sheath to the mesophyll (dark blue arrows), and re-shuttling of organic acids (light blue arrows). Enzymes highlighted in bold could be associated with an increased abundance of at least one transcript copy.

In contrast to the metabolite patterns, a C3–C4-related transcript pattern could not be detected in the PCA of Moricandia transcriptomes. The partly random enrichment of GO-terms in the commonly up- and down-regulated transcripts also suggested that species-specific differences had a major influence on the transcript pattern. The results differed considerably from the picture obtained for comparisons of transcriptomes from C3 and C4 species (Brautigam et al., 2011, 2014; Gowik et al., 2011), which were always characterised by a very strong C4 signature with very high abundance of all transcripts encoding the C4 photosynthesis proteins, including PEPC, PPDK, ME, NADP-MDH, AspAT, and adenosine monophosphate kinase (Brautigam et al., 2014). Changes in the Moricandia lines were on a much smaller scale, but some transcripts encoding enzymes associated with C4 metabolism, such as PPDK, PEPCK, a plastidic NADP-MDH, a cytosolic NAD-MDH, and three copies of AspAT, were also enhanced in both C3–C4 intermediate species. The same was true for one PEPC copy (Supplementary Table S5).

In Flaveria, only F. chorifoliae displayed a similar level of C3–C4 metabolism as the Moricandia species tested, with no significant contribution of PEPC and the C4 cycle. However, even this basic C3–C4 intermediate species showed increases in transcript abundance of AlaAT and NADP-ME, and these changes were associated with the operation of the N-balancing shuttle mechanisms. The fact that the transcript changes in the C3–C4 intermediate Moricandias were usually moderate or small compared with true C4 species supported the hypothesis that there was not one main shuttle operating. Not all steps predicted in the model shown in Fig. 8 were accompanied by increases in transcript levels. This might not be necessary because the required enzymes are not only present in a C3 background (Aubry et al., 2011), but also of high enough abundance. It is furthermore possible that transcripts did not change in their general abundance between C3 and C3–C4 species, but that they were affected in their post-transcriptional regulation or cellular distribution instead. Overall, metabolite as well as transcript patterns indicated that the N metabolism between MS and BS was adjusted by multiple pathways.

Redox balance requires transcriptional changes

When the GLD reaction is shifted to the BS, it increases not only the release of CO2 and NH4 in the BS mitochondria, but also produces high amounts of NADH (Fig. 8). In Moricandia, three AOX and one UCP transcripts were more abundant in the leaves of C3–C4 intermediate species than in the C3 relative, suggesting that re-balancing the redox metabolism of the mitochondria is supported by alternative electron transport. Increases in AOX are usually found under stress, but AOX expression is also affected in photorespiratory mutants (Voss et al., 2013). The association of enhanced alternative electron transport in C3–C4 photosynthesis could be verified by comparisons with the transcript patterns in different Flaveria species. Increases in AOX transcripts were also present in the intermediate species but they returned to C3 levels in the C4 species (Fig. 6), indicating that redox balance is harmonised again after full implementation of the C4 cycle. This model predicts the irretrievable loss of the mitochondrial NADH transported by the photorespiratory pump.

Anatomical and environmental constrains could be responsible for impeded evolution towards C4 in Moricandia

In the model presented by Mallmann et al. (2014), the initial shift of the GLD in the C3–C4 intermediates promotes a smooth transition to C4 by gradual enhancement of the C4 cycle, but it does not provide a straightforward explanation why some species remain stuck in intermediacy. In Moricandia, the analysis of potential C4 cycle genes indicated that they are expressed, albeit at low level, in the intermediates and are theoretically capable of forming a C4 cycle. So possible reasons for abidance of Moricandia in the C3–C4 state could be lack of time or the absence of some genetic, anatomic, or environmental drivers for the transition to C4 to take place (Mallmann et al., 2014; Heckmann, 2016).

Estimates of the time of split between C3 and C3–C4Moricandias are between 11 Ma (Fig. 1A) and 2 Ma (Arias et al., 2014). The same period was predicted to have passed since the separation of C3 and C3–C4 intermediate Diplotaxis species (Fig. 1A). In Flaveria, one of the youngest lines evolving C4 photosynthesis, C3–C4 metabolism is thought to have evolved about 3 Ma ago and, in at least one line, evolution to full C4 photosynthesis was completed about 1–0.5 Ma ago (Christin et al., 2011a). Although accurate timing of these evolutionary events is difficult, the results indicate that evolution from C3–C4 to C4 might have been generally possible in the 2–11 Ma that elapsed since the origin of C3–C4 in Moricandia, but it would probably depend on several beneficial pre-conditions. Stability of C3–C4 metabolism for several Ma has also been described for a second lineage in Flaveria (F. sonorensis; Christin et al., 2011a) and Mollugo (Christin et al., 2011b).

Environmental conditions promoting C4 evolution can generally be associated with conditions of high photorespiration, such as high temperatures and C limitation of photosynthesis, which can be found in hot, open environments with water limitation and high salinity (Osborne and Sack, 2012; Brautigam and Gowik, 2016). In many habitats, nutrients other than carbon, for example bio-available nitrogen or phosphorus, restrict plant growth (Korner, 2015). The low carboxylation efficiency of Moricandia intermediates, as indicated by low initial slopes in the A-Ci curves (Fig. 2C), point to low N-content in leaves (Sage et al., 1987), probably due to reduced levels of Rubisco and CBB cycle enzymes (Fig. 5). Lower leaf N-content was supported by higher C/N ratios and lower protein content per leaf dry-weight (Fig. 2). The advantages of intermediate Moricandias were thus probably limited to very low CO2 partial pressures, as occur when stomata are closed due to water limitations, while C3Moricandias reached higher assimilation rates under ambient CO2, as encountered when stomata are open. The low leaf protein content pointed to an evolutionary history of adaptation to N-limited environments. A comparison with A-Ci curves from other C3–C4 intermediate species showed that the phenotype is specific for Moricandia. In intermediate species of Heliotropium, the carboxylation efficiency of C3–C4 intermediates was slightly higher than in related C3 species (Vogan and Sage, 2011), and the carboxylation efficiency presented for C3–C4 intermediate Flaveria species are also similar to the C3 relatives (Dai et al., 1996). Expression of CBB cycle genes was only reduced in Flaveria species with at least C4-like metabolism, while transcription remained comparable to C3 species in all C3–C4 intermediates (Fig. 6; Mallmann et al., 2014). In both the C3–C4 intermediate Moricandia lines that were tested, on the other hand, the CBB cycle genes were already reduced at the basic intermediate state (Figs 5 and 6). Transcripts belonging to nitrogen as well as carbohydrate metabolism are enriched in the group of genes commonly reduced in the intermediate species. Thus, possibly both C and N limitation promoted the evolution of C3–C4 intermediacy in these species.

Finally, Moricandia provided new insights into the importance of anatomic enablers not only for the transition from C3 to C3–C4 but also for further evolution towards C4. Activation of BS cells and high vein density are essential pre-conditions for establishment of an efficient C4 cycle (Christin et al., 2013; Khoshravesh et al., 2016). The efficiency of the glycine shuttle and connected C- and N-balancing mechanisms depend on enhanced metabolite exchange between the MS and BS cells and are therefore also dependent on a limited distance between the two cell types. The importance of the narrow vein spacing increases with the increasing contribution of a C4 cycle in advanced C3–C4 intermediates and finally through to full C4 (McKown and Dengler, 2007). Plant families in which C4 photosynthesis evolved such as Flaveria and Heliotropium are generally characterised by vein densities considerably higher than in Moricandia (McKown et al., 2005; Muhaidat et al., 2011). It is therefore possible that limited anatomical pre-conditions hampered evolution to C4 in the Brassiceae.

Conclusions

Current models suggest that after implementation of the photorespiratory CO2 pump, re-balancing of N and C metabolism promotes further shuttle mechanisms involving C4 metabolites between the MS and BS cells, and finally installation of highly efficient C4 photosynthesis (Mallmann et al., 2014; Brautigam and Gowik, 2016). In Moricandia, the installation of a glycine shuttle was definitely successful, and they possessed BS-specific GLDP expression, low CO2 compensation points, and BS cells with a high number of centripetally arranged organelles. The metabolite pattern also suggests the activity of additional metabolite shuttles in the intermediates leaves. Establishment of the C4 cycle was apparently not hampered as the C4 cycle genes were present and expressed. Thus far, the situation in Moricandia does not look very different from Flaveria, but while some Flaveria lines progressed to C4, all Moricandia lines remained at the basic intermediate state. Lack of progression to C4 in the Brassicaceae could still be connected to chance, but our Moricandia data now provide evidence for possible constrains on the path to C4, namely anatomical limitation of efficient metabolite exchange or insufficient evolutionary pressure due to limitation in nutrients other than carbon, i.e. nitrogen. In contrast to C3–C4 lines with C4 relatives, intermediate Brassicaeae grow in colder climates (MR Lundgren and PA Christin, unpublished data), so pressure to reduce photorespiration might also be limited. In the end, limited environmental pressure and anatomical constrains might have led to metabolic balancing by multiple pathways rather that continued promotion of the C4 cycle in Moricandia. The analyses of additional intermediates with no closely related C4 species, especially with respect to their leaf architecture and N metabolism, will hopefully provide further glimpses into the evolution of intermediacy and of C4.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Figure S1. Phenotypes of the tested Moricandia lines.

Figure S2. Statistical summary of Moricandia metabolite patterns.

Figure S3. Statistical summary of Moricandia transcript patterns.

Table S1. ITS sequences extracted from the NCBI database.

Table S2. Sequences for the glycine decarboxylase P-protein.

Table S3.: Protocol for combined conventional and microwave-proceeded fixation, dehydration, and resin embedding of Moricandia leaf sections for histological and ultrastructural analysis.

Table S4. Summary of metabolite, element, gas exchange, anatomy, and protein measurements.

Table S5. Transcripts significantly different in abundance between the three Moricandia species (M. moricandioides, M. arvensis line MOR1 and M. suffruticosa)

Table S6. GO-terms enriched in commonly regulated transcripts in the comparison between C3–C4 and C3Moricandia species, but not different between the two C3–C4Moricandia species.

Table S7. Changes in abundance of transcripts belonging to selected pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The technical assistance of Maria Graf, Elisabeth Klemp, and Katrin L. Weber was greatly appreciated. The work was funded by the DFG Priority program ‘Adaptomics’ 1529, the 3to4 EU Collaborative Project, and the Cluster of Excellence on Plant Sciences CEPLAS (EXC1028).

References

- Adwy W, Laxa M, Peterhansel C. 2015. A simple mechanism for the establishment of C2-specific gene expression in Brassicaceae. The Plant Journal 84, 1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel P, Horstmann C, Pfeffer M. 1997. The Moricandia syndrome in species of the Brassicaceae – evolutionary aspects. Photosynthetica 33, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Arias T, Beilstein MA, Tang M, McKain MR, Pires JC. 2014. Diversification times, among Brassica (Brassicaceae) crops suggest hybrid formation after 20 million years of divergence. American Journal of Botany 101, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton AR, Burnell JN, Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Hatch MD. 1990. The enzymes in C4 photosynthesis. In: Lea PJ, Harborne JB, eds. Enzymes of primary metabolism. London, UK: Academic Press, 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry S, Brown NJ, Hibberd JM. 2011. The role of proteins in C3 plants prior to their recruitment into the C4 pathway. Journal of Experimantal Botany 62, 3049–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H, Apel P. 1979. Biochemical characterization of Moricandia arvensis (L.) DC., a species with features intermediate between C3 and C4 photosynthesis, in comparison with the C3 species Moricandia foetida Bourg. Biochemie und Physiologie der Pflanzen 174, 251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes G, Ogren WL, Hageman RH. 1971. Phosphoglycolate production catalyzed by ribulose diphosphate carboxylase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 45, 716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam A, Gowik U. 2016. Photorespiration connects C3 and C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimantal Botany 67, 2953–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam A, Kajala K, Wullenweber J, et al. 2011. An mRNA blueprint for C4 photosynthesis derived from comparative transcriptomics of closely related C3 and C4 species. Plant Physiology 155, 142–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam A, Schliesky S, Kulahoglu C, Osborne CP, Weber AP. 2014. Towards an integrative model of C4 photosynthetic subtypes: insights from comparative transcriptome analysis of NAD-ME, NADP-ME, and PEP-CK C4 species. Journal of Experimantal Botany 65, 3579–3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RH, Hattersley PW. 1989. Leaf anatomy of C3-C4 species as related to evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 91, 1543–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Osborne CP, Chatelet DS, Columbus JT, Besnard G, Hodkinson TR, Garrison LM, Vorontsova MS, Edwards EJ. 2013. Anatomical enablers and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in grasses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 1381–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Osborne CP, Sage RF, Arakaki M, Edwards EJ. 2011a C4 eudicots are not younger than C4 monocots. Journal of Experimantal Botany 62, 3171–3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Sage TL, Edwards EJ, Ogburn RM, Khoshravesh R, Sage RF. 2011b Complex evolutionary transitions and the significance of C3-C4 intermediate forms of photosynthesis in Molluginaceae. Evolution 65, 643–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Spriggs E, Osborne CP, Stromberg CA, Salamin N, Edwards EJ. 2014. Molecular dating, evolutionary rates, and the age of the grasses. Systematic Biology 63, 153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Ku MB, Edwards GE. 1996. Oxygen sensitivity of photosynthesis and photorespiration in different photosynthetic types in the genus Flaveria. Planta 198, 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dengler NG, Dengler RE, Donnelly PM, Hattersley PW. 1994. Quantitative leaf anatomy of C3 and C4 grasses (Poaceae): bundle sheath and mesophyll surface area relationships. Annals of Botany 73, 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7, 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Z, Zhou X, Ling Y, Zhang Z, Su Z. 2010. agriGO: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community. Nucleic Acids Research 38, W64–W70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel N, van den Daele K, Kolukisaoglu U, Morgenthal K, Weckwerth W, Parnik T, Keerberg O, Bauwe H. 2007. Deletion of glycine decarboxylase in Arabidopsis is lethal under nonphotorespiratory conditions. Plant Physiology 144, 1328–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiehn O, Kopka J, Dörmann P, Altmann T, Trethewey R, Willmitzer L. 2000. Metabolite profiling for plant functional genomics. Nature Biotechnology 18, 1157–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AE, McDade LA, Kiel CA, Khoshravesh R, Johnson MA, Stata M, Sage TL, Sage RF. 2015. Evolutionary history of Blepharis (Acanthaceae) and the origin of C4 photosynthesis in section Acanthodium. International Journal of Plant Sciences 176, 770–790. [Google Scholar]

- Gowik U, Brautigam A, Weber KL, Weber AP, Westhoff P. 2011. Evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the genus Flaveria: how many and which genes does it take to make C4?The Plant Cell 23, 2087–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, et al. 2013. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols 8, 1494–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. 1987. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 895, 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD, Slack CR. 1970. Photosynthetic CO2-fixation pathways. Annual Review of Plant Biology 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann D. 2016. C4 photosynthesis evolution: the conditional Mt. Fuji. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 31, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann D, Schulze S, Denton A, Gowik U, Westhoff P, Weber AP, Lercher MJ. 2013. Predicting C4 photosynthesis evolution: modular, individually adaptive steps on a Mount Fuji fitness landscape. Cell 153, 1579–1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday AS, Chollet R. 1983. Photosynthetic/photorespiratory carbon metabolism in the C3-C4 intermediate species, Moricandia arvensis and Panucum milioides. Plant Physiology 73, 740–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday AS, Harrison AT, Chollet R. 1982. Photosynthetic/photorespiratory CO2 exchange characteristics of the C3-C4 intermediate species, Moricandia arvensis. Plant Science Letters 27, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Holaday AS, Shien Y-J, Lee KW, Chollet R. 1981. Anatomical, ultrastructural and enzymatic studies of leaves of Moricandia arvensis, a C3-C4 intermediate species. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 637, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook GP, Jordan DB, Chollet R. 1985. Reduced apparent photorespiration by the C3-C4 intermediate species, Moricandia arvensis and Panicum milioides. Plant Physiology 77, 578–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt S, Smith AM, Woolhouse HW. 1987. Evidence for a light-dependent system for reassimilation of photorespiratory CO2, which does not include a C4 cycle, in the C3-C4 intermediate species Moricandia arvensis. Planta 171, 227–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylton CM, Rawsthorne S, Smith AM, Jones DA, Woolhouse HW. 1988. Glycine decarboxylase is confined to the bundle-sheath cells of leaves of C3-C4 intermediate species. Planta 175, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy RA, Laetsch WM. 1974. Plant species intermediate for C3, C4 photosynthesis. Science 184, 1087–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. 2002. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Research 12, 656–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshravesh R, Stinson CR, Stata M, Busch FA, Sage RF, Ludwig M, Sage TL. 2016. C3-C4 intermediacy in grasses: organelle enrichment and distribution, glycine decarboxylase expression, and the rise of C2 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimantal Botany 67, 3065–3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner C. 2015. Paradigm shift in plant growth control. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 25, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenzer EGJ, Moss DN, Crookston RK. 1975. Carbon dioxide compensation points of flowering plants. Plant Physiology 56, 194–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu M-JA, Gowik U, Kelly S, et al. 2015. RNA-Seq based phylogeny recapitulates previous phylogeny of the genus Flaveria (Asteraceae) with some modifications. BMC Evolutionary Biology 15, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallmann J, Heckmann D, Bräutigam A, Lercher MJ, Weber APM, Westhoff P, Gowik U. 2014. The role of photorespiration during the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the genus Flaveria. eLife 3, e02478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKown AD, Dengler NG. 2007. Key innovations in the evolution of kranz anatomy and C4 vein pattern in Flaveria (Asteraceae). American Journal of Botany 94, 382–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKown AD, Moncalvo J-M, Dengler NG. 2005. Phylogeny of Flaveria (Asteraceae) and interference of C4 photosynthesis evolution. American Journal of Botany 92, 1911–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BD, Franceschi VI, Shu-Hua C, Wu J, Ku MB. 1987. Photosynthetic charcteristics of the C3-C4 intermediate Parthenium hystophorus. Plant Physiology 85, 984–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CL, Turner SR, Rawsthorne S. 1993. Coordination of the cell-specific distribution of the four subunits of glycine decarboxylase and serine hydroxymethyltransferase in leaves of C3–C4 intermediate species from different genera. Planta 190, 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- Muhaidat R, Sage TL, Frohlich MW, Dengler NG, Sage RF. 2011. Characterization of C3–C4 intermediate species in the genus Heliotropium L. (Boraginaceae): anatomy, ultrastructure and enzyme activity. Plant, Cell & Environment 34, 1723–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Kane SLJ, Schaal BA, Al-Shehbaz IA. 1996. The origins of Arabidopsis suecica (Brassicaceae) as indicated by nuclear rDNA sequences. Systematic Botany 21, 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne CP, Sack L. 2012. Evolution of C4 plants: a new hypothesis for an interaction of CO2 and water relations mediated by plant hydraulics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 367, 583–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus JK, Schlieper D, Groth G. 2013. Greater efficiency of photosynthetic carbon fixation due to single amino-acid substitution. Nature Communications 4, e1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendrudu G, Prasad JSR, Das VSR. 1986. C3-C4 intermediate species in Alternathera (Amaranthaceae). Plant Physiology 80, 409–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S. 1992. C3-C4 intermediate photosynthesis: linking physiology to gene expression. The Plant Journal 2, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM. 1991. The relatonship between post-illumination CO2 burst and glycine metabolism in leaves of C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia. Planta 186, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM, Smith AM, Woolhouse HW. 1988a Distribution of photorespiratory enzymes between bundle-sheath and mesophyll cells in leaves of the C3-C4 intermediate species Moricandia arvensis (L.) DC. Planta 176, 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne S, Hylton CM, Smith AM, Woolhouse HW. 1988b Photorespiratory metabolism and immunogold localization of photorespiratory enzymes in leaves of C3 and C3-C4 intermediate species of Moricandia. Planta 173, 298–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. 2010. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylott EL, Methlaff K, Rawsthorne S. 1998. Development and environmental effects on the expression of the C3-C4 intermediate phenotype in Moricandia arvensis. Plant Physiology 118, 1277–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2004. The evolution of C4 photosynthesis. New Phytologist 161, 341–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2016. A portrait of the C4 photosynthetic family on the 50th anniversary of its discovery: species number, evolutionary lineages, and Hall of Fame. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 4039–4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Christin PA, Edwards EJ. 2011a The C4 plant lineages of planet Earth. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 3155–3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Khoshravesh R, Sage TL. 2014. From proto-Kranz to C4 Kranz: building the bridge to C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3341–3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Pearcy RW, Seemann JR. 1987. The nitrogen use efficiency of C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiology 85, 355–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Sage TL, Kocacinar F. 2012. Photorespiration and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63, 19–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage TL, Sage RF, Vogan PJ, Rahman B, Johnson DC, Oakley JC, Heckel MA. 2011b The occurrence of C2 photosynthesis in Euphorbia subgenus Chamaesyce (Euphorbiaceae). Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 3183–3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre RT, Kennedy RA. 1977. Ecotypic differences in the C3 and C4 photosynthetic activity in Mollugo verticillata, a C3-C4 intermediate. Planta 134, 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter U, Weber AP. 2016. The road to C4 photosynthesis: evolution of a complex trait via intermediary states. Plant and Cell Physiology 57, 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze S, Mallmann J, Burscheidt J, Koczor M, Streubel M, Bauwe H, Gowik U, Westhoff P. 2013. Evolution of C4 photosynthesis in the genus Flaveria: establishment of a photorespiratory CO2 pump. The Plant Cell 25, 2522–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M, Watts R. 2010. Moricandia. In: Kole C, ed. Wild crop relatives: genomic and breeding resources. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno O. 2003. Structural and biochemical dissection of photorespiration in hybrids differing in genome constitution between Diplotaxis tenuifolia (C3-C4) and radish (C3). Plant Physiology 132, 1550–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno O. 2011. Structural and biochemical characterization of the C3-C4 intermediate Brassica gravinae and relatives, with particular reference to cellular distribution of Rubisco. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 5347–5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno O, Wada Y, Wakai M, Bang SW. 2006. Evidence from photosynthetic characteristics for the hybrid origin of Diplotaxis muralis from a C3-C4 intermediate and a C3 species. Plant Biology 8, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogan PJ, Sage RF. 2011. Water-use efficiency and nitrogen-use efficiency of C3 -C4 intermediate species of Flaveria Juss. (Asteraceae). Plant, Cell & Environment 34, 1415–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S. 2000. Biochemical models of leaf photosynthesis. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Voss I, Sunil B, Scheibe R, Raghavendra AS. 2013. Emerging concept for the role of photorespiration as an important part of abiotic stress response. Plant Biology 15, 713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warwick SI, Sauder CA. 2005. Phylogeny of tribe Brassiceae (Brassicaceae) based on chloroplast restriction site polymorphisms and nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer and chloroplast trnL intron sequences. Canadian Journal of Botany 83, 467–483. [Google Scholar]