Evolution of C3–C4 intermediate and C4 lineages are resolved in Salsoleae (Chenopodiaceae), and a model for structural and biochemical changes for the evolution of the Salsoloid form of C4 is considered.

Keywords: Ancestral character state reconstruction, C2 pathway, C3–C4 intermediates, CO2 compensation point, leaf anatomy, TEM, western blots

Abstract

While many C4 lineages have Kranz anatomy around individual veins, Salsoleae have evolved the Salsoloid Kranz anatomy where a continuous dual layer of chlorenchyma cells encloses the vascular and water-storage tissue. With the aim of elucidating the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Salsoleae, a broadly sampled molecular phylogeny and anatomical survey was conducted, together with biochemical, microscopic, and physiological analyses of selected photosynthetic types. From analyses of photosynthetic phenotypes, a model for evolution of this form of C4 was compared with models for evolution of Kranz anatomy around individual veins. A functionally C3 proto-Kranz phenotype (Proto-Kranz Sympegmoid) and intermediates with a photorespiratory pump (Kranz-like Sympegmoid and Kranz-like Salsoloid types) are considered crucial transitional steps towards C4 development. The molecular phylogeny provides evidence for C3 being the ancestral photosynthetic pathway but there is no phylogenetic evidence for the ancestry of C3–C4 intermediacy with respect to C4 in Salsoleae. Traits considered advantageous in arid conditions, such as annual life form, central sclerenchyma in leaves, and reduction of surface area, evolved repeatedly in Salsoleae. The recurrent evolution of a green stem cortex taking over photosynthesis in C4 clades of Salsoleae concurrent with leaf reduction was probably favoured by the higher productivity of the C4 cycle.

Introduction

Reconstructing the evolution of C4 photosynthesis is challenging as it requires the complex coordination of anatomical, ultrastructural, biochemical, and gene regulatory changes from C3 ancestors (Hibberd and Covshoff, 2010; Gowik and Westhoff, 2011; Sage et al., 2012, 2014; Williams et al., 2012; Hancock and Edwards, 2014). In bringing together these aspects, a model of C4 evolution where Kranz anatomy is formed around individual veins has been developed over the last 30 years, which includes potential evolutionary precursors and a number of transitional, evolutionary-stable states (Monson et al., 1984; Edwards and Ku, 1987; Sage, 2004; Gowik and Westhoff, 2011; Sage et al., 2012, 2014). These hypothetical states are based on distinct phenotypes observed in nature in close relatives of C4 lineages and are characterized by a combination of C3 and C4 characteristics. From these, a stepwise progression from C3 to proto-Kranz to photosynthetic intermediates, and finally to C4 photosynthesis was proposed with a progressive reduction in photorespiration (Sage et al., 2014; hereafter named the ‘Flaveria model’ based on photosynthetic phenotypes studied in this genus).

In dicots, there are many anatomical forms of Kranz anatomy that differ in the arrangement of a dual layer of chlorenchyma cells performing the C4 pathway. These includes forms where Kranz anatomy develops around individual veins; however, there are also nine forms where two concentric chlorenchyma layers surround all veins (Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011). According to Brown (1975), in C4 plants we refer to cells of the inner chlorenchyma layer that become specialized for C4 photosynthesis, irrespective of their position in the leaf, as Kranz cells (KC) and the outer layer as mesophyll (M) cells (Edwards and Voznesenskaya, 2011; Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). In C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes the inner layer of chlorenchyma, which has become specialized to support the C2 cycle, is referred to as Kranz-like cells (KLC; Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). In C3 species vascular bundles (VB) are surrounded by non-specialized parenchymatic bundle sheath (BS) cells.

Proto-Kranz phenotypes, first described in Heliotropium and Flaveria, are suggested to represent the initial phase of C4 evolution where overall vein density is increased and BS cells have an increased number of organelles, with enlarged mitochondria located internally to chloroplasts in a centripetal position towards the VB (Muhaidat et al., 2011; Sage et al., 2012, 2013, 2014). C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes, which have been found in grasses and in a number of dicot families, have in common increased development of chloroplasts and mitochondria in the KLCs. Both M and KLC chloroplasts have Rubisco and the C3 cycle. In the KLCs there is a distinctive layer of mitochondria that are located internally to the chloroplasts in a centripetal position. In C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes glycine decarboxylase (GDC) is selectively localized in the KLC mitochondria, which support a C2 cycle by establishing a photorespiratory CO2 pump. In the C2 cycle photorespiratory glycine produced in the M cells is shuttled for decarboxylation by GDC to the KLCs where photorespired CO2 is concentrated, enhancing its capture by KLC Rubisco (see Edwards and Ku, 1987; Sage et al., 2012, 2014; Voznesenskaya et al., 2013; Khoshravesh et al., 2016).

For the ‘Flaveria model’ C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes have been classified into two general groups: Type I and Type II C3–C4 species (Edwards and Ku, 1987; alternatively called Type 1 C2 and Type 2 C2, Sage et al., 2014). Type I C3–C4 species have developed little or no capacity for function of a C4 cycle as activities/quantities of C4 enzymes are low, similar to C3 species. These intermediates mainly reduce losses of the CO2 generated by photorespiration by its partial refixation in the KLCs. Type II intermediates have substantial expression of a C4 cycle; e.g. the levels of the C4 cycle enzymes phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC), pyruvate phosphate dikinase (PPDK), and NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) are two- to five-fold higher in Type II C3–C4 species than in C3 species (Ku et al., 1983, 1991; Edwards and Ku, 1987; Moore et al., 1987; Muhaidat et al., 2011; Sage et al., 2012). The values of CO2 compensation points (Γ) in C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes are in between those of C3 and C4 species.

The fact that C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes thrive, persist, and occasionally have been found in lineages without any C4 relatives, suggests that they represent an evolutionary-stable condition in their own right (Monson et al., 1984; Edwards and Ku, 1987). Their predominant occurrence close to C4 groups may be strongly biased by the more intensive screening in these lineages. Thus, C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes do not necessarily represent transitional states that always lead to the establishment of C4 photosynthesis. A C2 cycle might already be favourable in conditions of high photorespiration, e.g. in hot, dry, and saline environments (Keerberg et al., 2014). The ‘Flaveria model’ is functionally plausible, and supported by phenotypes that actually exist in nature (Sage et al., 2014); however, phylogenetic evidence for the ancestry of the C3–C4 intermediate condition is scarce, and is hampered by the generally low number of species with intermediate phenotypes.

C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes have been recognized in 16 angiosperm genera (Sage et al., 2012, 2014; Khoshravesh et al., 2016). Often, the ancestry of the C3–C4 intermediate condition is inferred from a sister-group relationship of a C4 lineage and a C3–C4 intermediate lineage (Sage et al., 2011, 2012) because the intermediate condition is a priori considered as less derived. However, in such cases it is impossible to distinguish between ancestry and a de novo evolution of the C3–C4 intermediate condition (compare with Hancock and Edwards, 2014). If those cases in which C3–C4 intermediate photosynthesis seems to precede C4 photosynthesis, as suggested in Sage et al. (2011; 2012), are critically tested for unequivocal phylogenetic evidence, only Flaveria (Asteraceae) studied by McKown et al. (2005) holds up. In this case, a stepwise acquisition of C4 photosynthesis in one lineage of Flaveria was shown (McKown et al., 2005; Lyu et al., 2015).

There are four other promising groups that are rich in C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes and therefore potentially informative lineages in terms of disentangling the steps of C4 evolution and ancestral state reconstruction for C3–C4 intermediacy: Blepharis (Fisher et al., 2015), Anticharis (Khoshravesh et al., 2012), Heliotropium (Sage et al., 2012), and Salsoleae sensu stricto (s.s.; Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). A better understanding of C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes in Salsoleae is particulary important as these, in contrast to the other groups, seem to deviate from the ‘Flaveria model’ (see ‘Salsoleae model’, Voznesenskaya et al., 2013).

Salsoleae, especially the former section Coccosalsola, has long been known to contain C3 and C4 species (Winter, 1981; Akhani et al., 1997). In fact, Salsoleae has repeatedly been suspected to contain species that represent reversions from C4 back to C3 photosynthesis (Carolin et al., 1975; P’yankov et al., 1997; Kadereit et al., 2014); however, this has been questioned by Kadereit et al. (2003). According to a survey by Voznesenskaya et al. (2013, see table 5) there are at least 21 species with δ13C values within the typical range of C3 species in Salsoleae. So far, four of these have been shown to possess either proto-Kranz (Salsola montana), or a C3–C4 intermediate phenotype (S. arbusculiformis, S. divaricata, and S. laricifolia (Voznesenskaya et al., 2013 and references therein; Wen and Zhang, 2015). In the ‘Flaveria model’ Kranz anatomy is formed around individual veins, requiring a series of anatomical changes in progression from C3 to C4. In Salsoleae, however, the photosynthetic tissue in leaves forms a continuous layer that surrounds all the vascular and water-storage tissue, i.e. in C3 species by multiple layers of mesophyll tissue (Sympegmoid-type anatomy), and in C4 species by a dual layer of chlorenchyma tissue forming a Kranz anatomy (Salsoloid-type anatomy). Voznesenskaya et al. (2013) proposed a model for transitions from C3 to proto-Kranz to C3–C4 intermediates to C4 in Salsoleae, based on limited photosynthetic phenotypes, which would require very different changes in leaf anatomy and regulation of development of the dual layer of chlorenchyma cells compared to that in the ‘Flaveria model’ for development of Kranz anatomy around individual veins.

Here, we conduct a large-scale analysis of Salsoleae, including species with C3-type δ13C values. The results of a molecular phylogenetic study of 74 species and an anatomical survey of 77 species of Salsoleae s.s, and some outgroup species, are presented. Furthermore, in a search for additional C3–C4 intermediates in the tribe, anatomical, ultrastructural, enzyme content, and gas exchange analyses were performed on a number of species that have C3-type δ13C values. Molecular clock and character optimization analyses were used to reconstruct the evolution of the C4 pathway in Salsoleae. The following questions were addressed. (1) Is there evidence for additional C3–C4 intermediates in Salsoleae? (2) What is the current model for evolution of C4 in Salsoleae based on analyses of photosynthetic phenotypes? (3) In what ways does this model differ from the ‘Flaveria model’ proposed in Sage et al. (2012, 2014)? (4) Where and when did C4 photosynthesis originate in Salsoleae, and is there phylogenetic evidence for a reversion from C4 back to C3? (5) Does the C3–C4 intermediate condition represent an ancestral state to C4 in Salsoleae?

Material and methods

Plant material and sampling

Species and samples included in the analyses with their respective voucher information are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online. We used herbarium samples and plants grown in the greenhouse at the Botanical Gardens of the University of Mainz, Germany, and at Washington State University (WSU), Pullman, WA, USA, and leaves of specimens that were fixed during various expeditions, mainly by H. Freitag. A few samples were kindly provided by other institutions. Species of the Kali clade were mostly left out, because in the trees based on chloroplast sequence data they are separated from the Salsoleae s.s.

In WSU, plants were grown in 15-cm diameter pots with commercial potting soil in a growth chamber (model GC-16; Enconair Ecological Chambers Inc., Winnipeg, Canada) under a 14/10 h 25/18 °C day/night cycle under mid-day PPFD of ~500 μmol quanta m−2 s−1, and 50% relative humidity for ~2 months. Plants were watered daily and fertilized once per week with Peter’s Professional fertilizer (20:20:20 Scotts Miracle-Gro, Marysville, OH, USA).

Our sampling of Salsoleae for the molecular phylogenetic analyses comprised 74 species representing all currently accepted genera (Supplementary Table S2) and included 15 species with C3-like carbon isotope (δ13C) values (compare with table 5 in Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). Furthermore, representatives of other primary clades of Salsoloideae (Supplementary Table S2) as well as representatives of Camphorosmoideae were included. For rooting and dating purposes Suaedoideae and Salicornioideae were sampled as outgroups (Supplementary Table S1). For light microscopy 77 species were examined, mostly from the same material (Supplementary Table S1), including 34 species studied for the first time. Data for eight species were taken from the literature. Six species having different anatomical types (most not previously known in that respect) were chosen for study by electron microscopy, and δ13C, in situ immunolocalization, western blot, and gas exchange analyses.

With respect to nomenclature, apart from a few exceptions we follow previous accounts of the different subfamilies, in particular Botschantzev (1989), Akhani et al. (2007), and Kadereit and Freitag (2011), although we are aware that more nomenclatural adjustments are required.

Sequencing and phylogenetic inference

Total DNA was extracted from dried or fresh leaf material using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) or innuPREP Plant DNA Kit (Analytik Jena, Germany) following the manufacturers’ protocols but increasing incubation times. PCRs for five markers (atpB-rbcL intergenic spacer, ndhF-rpL32 spacer, trnQ-rps16 spacer, rpl16 intron, ITS) were carried out in a T-Professional or T-Gradient Thermocycler (Biometra, Germany), or a PTC100 Thermocycler (MJ Research, USA). Primers sequences, PCR recipes, and cycler programs are documented in Supplementary Table S3. PCR products were checked on 0.8% agarose gels and purified using the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR clean-up-Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany) or ExoSAP (Affymetrix, USA) following the manufacturers’ instructions. The Big Dye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems) combined with the primers mentioned above was used for the sequencing reactions, followed by a purification step using IllustraTM SephadexTM G-50 Fine DNA Grade (GE Healthcare, UK). Sequencing was performed following the Sanger method on a 3130xI Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., USA). The raw forward and reverse sequences were checked and automatically aligned in Sequencher 4.1.4 (Gene Codes Corporation, USA). The refined alignment was performed in Mesquite 2.75 (http://mesquiteproject.org) and carefully checked visually. The program SequenceMatrix (v. 1.7.8; Vaidya et al., 2011) was used to combine the four chloroplast (cp) marker data sets.

Phylogenetic analyses under the settings outlined below were initially conducted individually for the five selected DNA regions. Results of the individual analyses of the four cp markers revealed no topological conflict [i.e. incongruence with ML Bootstrap ≥65% and Posterior Probability (PP) ≥0.90] among individual markers and combination of the cp markers distinctly increased the resolution and support values. For the cp data further analyses were performed using two large and different data sets: (1) a data set with 106 taxa (106t data set) including a broad outgroup sampling; and (2) a data set with 75 taxa (75t data set) in which only Salsola genistoides served as the outgroup. The 106t data set was used to reveal primary clades in Salsoloideae and for estimation of divergence time, whereas the 75t data set was used for character optimization (see below). Since the ITS tree and the cp tree showed supported conflict at basal branches, and the combination of cp data and ITS for the 75t data set led to a significant decrease of resolution and support values in some parts of the tree, we concentrated on the cp tree for further analyses and only include the ITS tree for comparison. First, the best-fitting substitution model for the combined cp data sets was inferred using jModelTest (Posada, 2008). CIPRES (Cyberinfrastructure for Phylogenetic Research) Science Gateway V. 3.3. ML phylogenetic analyses were performed using RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006; Stamatakis et al., 2008), including bootstrapping that was halted automatically following the majority-rule ‘autoMRE’ criterion. Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was conducted using BEAST (Bayesian Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees v.1.8.2; Drummond and Rambaut, 2007) with GTR+G (general time-reversible; best-fitting according to jModeltest under AIC criterion) with a gamma-distribution in four categories as the substitution model. A birth-and-death demographic model was used as the tree prior. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis was performed with the following settings: randomly generated starting tree, 20 000 000 (106t data set) or 10 000 000 iterations (75t data set), discarded burn-in of 10%, and sampling every 1000 steps (totalling 10 000). For the 106t data set a relaxed clock model was implemented in which rates for each branch are drawn independently from an exponential distribution (Drummond et al., 2006). The crown node of Salsoloideae and Camphoromoideae was set to 47.0–25.5 mya based on divergence-time estimates in the Chenopodiaceae/Amaranthaceae complex (Kadereit et al., 2012). We assumed a uniform distribution within the age bounds set. Other settings were left in default.

Light and electron microscopy

For light microscopy, after routine checks by manual sectioning, the middle parts of well-developed leaves were selected for transections by a rotary microtome (Leitz 1515). The semi-thin sections of material fixed in FAA [2% (v/v) formaldehyde, 0.5% (v/v) acetic acid, 70% (v/v) ethanol] were studied under a Dialux 20 (Leitz, Wetzlar). Some were first examined and photographed in water to get a better contrast between lignified (blue) and non-lignified (purple) cell walls before embedding into Depex (Serva) for documentation. For detailed study, middle parts of fully developed leaves were fixed and processed in a similar way to that described in Voznesenskaya et al. (2013).

For screening purposes, leaf samples from herbarium specimens were first boiled for about 1–3 minutes and hand-cut sections were preserved in glycerol–gelatin. Selected samples for microtome transections were soaked in a 10% solution of NH3 for 10 d, dehydrated in ethanol, and embedded in Technovit 7100 (Heraeus Kulzer). The samples were sectioned at 5–20 µm using a rotary microtome. Sections were stained in a 6:6:5:6 mixture of Azur II, Eosin Y, methylene blue, and distilled water and mounted in Eukitt (O. Kindler) after drying. Images of the sections were taken using a Leitz Diaplan light microscope combined with Leica Application Suite 2.8.1.

For ultrastructural characterization, ultra-thin sections were taken from the same samples prepared for the light microscopy study and embedded in Spurr’s resin as described in Voznesenskaya et al. (2013). The number and sizes of mitochondria in chlorenchyma cells were estimated per cell section (about 10–15 cell images from 2–3 separate leaf samples) using an image analysis program (ImageJ 1.37v, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html).

δ13C values

Carbon isotope composition of plant samples was determined at Washington State University using a standard procedure relative to PDB (Pee Dee Belemnite) limestone as the carbon isotope standard (Bender et al., 1973). Leaf samples (from plants growing in the WSU growth chamber) were dried at 60 °C for 24 h, and then 1–2 mg were placed in a tin capsule and combusted in a Eurovector elemental analyser. The resulting N2 and CO2 gases were separated by gas chromatography and admitted into the inlet of a Micromass Isoprime isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) for determination of 13C/12C ratios (R). δ13C values were determined where δ = 1000 × (Rsample/Rstandard) − 1.

In situ immunolocalization

Sample preparation and immunolocalization by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were carried out according to Voznesenskaya et al. (2013). The antibody used (raised in rabbit) was against the P subunit of glycine decarboxylase (GDC) from Pisum sativum L. (courtesy of D. Oliver, Iowa State University). Pre-immune serum was used for controls. The density of labeling was determined by counting the gold particles on electron micrographs and calculating the number per unit area (µm2) using ImageJ 1.37v. For each cell type, replicate measurements were made on parts of cell sections (n = 10–15 cell images). Immunolabeling procedures were performed separately for different species; the difference in the labeling intensity reflects the difference between cell types but not between species. The level of background labeling was low in all cases.

Western blot analysis

Extraction of total soluble proteins, protein separation, and blotting onto a nitrocellulose membrane were carried out according to Voznesenskaya et al. (2013). A loading control with protein samples (20 µg) separated by 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1. Western blots were performed using anti-Amaranthus hypochondriacus NAD-malic enzyme (NAD-ME) IgG, which was prepared against the 65-kDa α subunit (courtesy of J. Berry; Long and Berry, 1996) (1:5000), anti-Zea mays 62-kDa NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME) IgG (courtesy of C. Andreo; Maurino et al., 1996) (1:5000), anti-Zea mays PEPC IgG (1:100 000), and anti-Zea mays pyruvate,Pi dikinase (PPDK) IgG (courtesy of T. Sugiyama) (1:5000). The intensities of bands in western blots were quantified using ImageJ 1.37v and expressed relative to the level in the C4 species S. oppositifolia, which was set at 100%.

CO2 compensation point

Measurements of CO2 compensation points (Γ) were made on an individual lateral branch using a Li-Cor lighted chamber (LI-6400-22L; Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) designed for terete or semi-terete conifer leaves. For each species, a part of a branch of an intact plant was enclosed in the chamber and illuminated with a PPFD of 1000 μmol quanta m−2 s−1 under 400 μmol mol−1 CO2 at 25 ºC until a steady-state rate of CO2 fixation was obtained (generally 45–60 min). For varying CO2 experiments, the CO2 level was first decreased, and then increased up to 400 μmol mol−1 at 5 min intervals. Γ was determined by extrapolation of the initial slope of rate of CO2 fixation (A) versus the intercellular CO2 concentration in the leaf (Ci) through the x-axis where the net rate of CO2 assimilation equals zero. The leaf area exposed to the incident light was calculated by taking a digital image of the part of the branch that was enclosed in the chamber, and then determining the exposed leaf area using ImageJ 1.37v.

Statistical analysis

Where indicated, standard errors were determined, and ANOVA was performed using Statistica 7.0 software (StatSoft, Inc.). Tukey’s HSD (honest significant difference) test was used to analyze differences between amounts of gold particles in BS/KLC/KC versus M for each species, and δ13C and Г values in different species. All analyses were performed at the 95% significance level.

Character coding and analyses of character evolution

Analyses of character evolution were conducted for five traits: (1) type of photosynthesis; (2) KC/KLC function; (3) life form; (4) leaf sclerenchyma; and (5) leaf reduction (Table 1). Traits were optimized over 1000 trees of 74 Salsoleae and Salsola genistoides as the outgroup obtained in a Bayesian analysis (see above) using the ML criterion in Mesquite (http://mesquiteproject.org). The fit of single- versus two-rate models was tested for traits with two character states using a likelihood ratio test. Table 1 gives information about the coding of the character states of the five traits.

Table 1.

Traits of photosynthetic pathway, leaf anatomy and life form in Salsoleae s.s. Trait 1: type of photosynthesis according to carbon isotope value; coding trait 2: C3 = 0, C4 = 1. Trait 2: function of bundle sheath (BS), Kranz-like (KLC) and Kranz cells (KC); coding trait 2: C3 type BS cells around peripheral VB (few or no organelles) = 0, KLC with increased number of organelles mostly in centripetal position, GDC only expressed in KLC cells, C3-C4 species = 1, C4 type Kranz cells = 2. Trait 3: Life form according to standard floras and our own observations in the field; coding trait 3: perennial l = 0, annual = 1. Trait 4: presence of sclerenchyma by replacement of major parts of the central water storage tissue; coding trait 4: no = 0, yes = 1. Trait 5: sites of major photosynthetic function; coding trait 5: predominantly in leaves and leaf-like structures (0), ± equally in leaves and stems (1), predominantly in stems due to reduction of leaves or their trans-formation into thorns (2). References for photosynthetic pathway and leaf anatomy see below table. Species are classified according to carbon isotope composition of leaf tissue as C3 or C4. Species are classified as C3, proto-kranz, C3-C4 intermediates, and C4 based on analyses of leaf anatomy, Trait 2 and C isotope composition, (see text).

| Species of Salsoleae s.s. | Isolate no. for molecular analysis | Trait 1: Type of photosynthesis according to carbon isotope ratio | Leaf anatomy; type names according to Voznesenskaya et al. (2013) | Trait 2 | Trait 3 | Trait 4 | Trait 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anabasis aphylla L. | chen 2743/2017 | C4 (1, 2, 12) | salsoloid+H (1, 6, 8, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anabasis articulata (Forssk.) Moq. | chen 2360 | C4 (7) | salsoloid+H (6, 8, 12, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anabasis brevifolia C.A. Mey. | chen 2407 | C4 (12) | salsoloid+H (2, 11, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Anabasis calcarea (Charif & Aellen) Bokhari & Wendelbo | chen 1841 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (1, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anabasis ehrenbergii Schweinf. ex Boiss. | chen 2403/2741 | C4 (12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Anabasis setifera Moq. | chen 2373 | C4 (7) | salsoloid+H (1, 2, 6, 12, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Arthrophytum betpakdalense Korov. | chen 0229 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Arthrophytum gracile Aellen | chen 2603 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Arthrophytum lehmannianum Bunge | chen 2637 | C4 (4) | salsoloid+H (5, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cornulaca amblyacantha Bunge | chen 0350 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cornulaca monacantha Delile | chen 0212 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid+H+S (2, this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cornulaca setifera (DC.) Moq | chen 0304 | C4 (12) | salsoloid+H+S (6, this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cyathobasis fruticulosa (Bunge) Aellen | chen 0082 | C4 (12) | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Girgensohnia diptera Bunge | chen 2639 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Girgensohnia minima E. Korov. | chen 2601 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Girgensohnia oppositiflora (Pall.) Fenzl | chen 0033 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid+H+S (2, 6, this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | (1)2 |

| Gyroptera gillettii Botsch | chen 2819 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Halogeton alopecuroides (Delile) Moq. | chen 0300 | C4 (1, 7, 12) | salsoloid+H (6, 8, 12, this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Halogeton arachnoideus Moq. | chen 2605 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Halogeton glomeratus (M. Bieb.) C.A. Mey. | chen 0030 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (2) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Halogeton sativus (L.) Moq. | chen 1229 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (8, this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Halothamnus bottae Jaub. & Spach | chen 0351 | C4 (12) | salsoloid (7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Halothamnus ferganensis Botsch. | chen 0197 | C4 ** | salsoloid (7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Halothamnus iliensis (Lipsky) Botsch. | chen 2668 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid (7) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Halothamnus somalensis (N.E. Br.) Botsch. | chen 2584 | C4 ** | salsoloid (7) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Haloxylon ammodendron (C.A. Mey.) Bunge | chen 0035 | C4 (1, 2, 12) | salsoloid+H (11, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Haloxylon persicum Bunge ex Boiss. | chen 2815 | C4 (7, 12) | salsoloid+H (11) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada articulata (Moq.) O. Bolos & Vigo | chen 0196 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (2, 6, this study)) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada eriantha Botsch. | chen 2813 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada griffithii (Moq.) Iljin | chen 2635 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Hammada negevensis Iljin & Zoh. | chen 2814 | C4 (7, 12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada salicornica (Moq.) Iljin | chen 2752 | C4 (1, 7) | salsoloid+H (2, 8, 12, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada schmittiana (Pomel) Botsch. | chen 2629 | C4 (7, 12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Hammada thomsonii (Bunge) Iljin | chen 0178 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Horaninowia capitata Sukhor. | chen 0188 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Horaninowia platyptera Charif & Aellen | chen 2602 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H+S (this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Horaninowia ulicina Fisch. & C.A. Mey. | chen 2589 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H+S (15, this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Iljinia regelii (Bunge) Korovin | chen 0182 | C4 (4) | salsoloid+H (11, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lagenantha cycloptera (Stapf) M.G. Gilbert & Friis | chen 2809 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Noaea minuta Boiss. & Bal. | chen 0079 | C4 (12) | salsoloid+S (this study) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Noaea mucronata (Forssk.) Asch. & Schweinf. | chen 0019 | C4 (1, 2, 7) | salsoloid+S (6, 9, this study) | 2 | 0 | 1 | (1)2 |

| Nucularia perrinii Batt. | chen 2627 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (8, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhaphidophyton regelii (Bunge) Iljin | chen 0075 | C3 (4) | kranz-like salsoloid+S (this study) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Salsola abrotanoides Bunge | chen 2996 | C3 (4, 6, 9) | sympegmoid (11, this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola acutifolia (Bunge) Botsch. | chen 2640 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola arbusculiformis Drob. | chen 0176 | C3 (1, 2, 6, 8, 11) | kranz-like sympegmoid (13, 16, this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola botschantzevii Kurbanov | chen 2630 | C3 (9) | proto-kranz sympegmoid (this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola cyrenaica (Maire & Weiller) Brullo | chen 0354 | C4 (9) | salsoloid+H (3, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola deschaseauxiana Litard. & Maire | chen 2758 ( = 2641) | C3 (9) | kranz-like salsoloid (this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola divaricata Masson ex Link | chen 2779 | C3 (6, 9) | kranz-like salsoloid (14, this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola drobovii Botsch. | chen 0175 | C3 (4, 6, 9) | proto-kranz sympegmoid (this study)*** | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola florida (M. Bieb.) Poir. | chen 2811 | C4 (1, 12) | salsoloid+H (2, 6, this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola foliosa (L.) Schrad. | chen 0103 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (11, this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola grandis Freitag, Vural & N. Adιgüzel | chen 0105 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (4, this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola gymnomaschala Maire | chen 0355 | C3 (9) | kranz-like salsoloid (this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola junatovii Botsch. | not included | C3 (9) | proto-kranz sympegmoid (this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola kerneri (Woł.) Botsch. | chen 2642 | C4 (1, 6) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola laricifolia Turcz. ex Litv. | chen 1355 | C3 (6, 9, 10, 11) | kranz-like salsoloid (14, 15, 16, this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola lipschitzii Botsch. | not included | C3 (9) | proto-kranz sympegmoid (this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola melitensis Botsch. | chen 2644 | C4 (9) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola montana Litv. | chen 2591 | C3 (1, 2, 5, 6, 9) | proto-kranz sympegmoid (14) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola oppositifolia Desf. | chen 0099 | C4 (1, 6, 9, 12) | salsoloid+H (8, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola oreophila Botsch. | chen 2847 | C3 (5, 9) | sympegmoid (10, this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola pachyphylla Botsch. | chen 2762 | C3 (5, 6) | sympegmoid (11, this study)) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola rosmarinus (Ehrenb. ex Boiss.) Akhani | chen 0303 | C4 (1, 7) | salsoloid+H (2, 6, this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola schweinfurthii Solms-Laub. | chen 2827 | C4 (1, 6, 7, 12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola soda L. | chen 2834 | C4 (1, 7) | salsoloid+H (9, this study) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola stocksii Boiss. | chen 2646 | C4 (1) | salsoloid+H (2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Salsola tianschanica Botsch. | not included | C3 (9) | sympegmoid (this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola tunetana Brullo | chen 2647 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola verticillata Schousboe | chen 2648 | C3 (this study)* | kranz-like salsoloid (this study) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola webbii Moq. | chen 2828 | C3 (1, 6, 9, 12) | sympegmoid (2, 8, 14, this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola zygophylla Batt. & Trab. | chen 2756 | C4 (1, 6, 12) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola zygophylloides (Aellen & Townsend) Akhani | chen 2593 | C4 ** | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sevada schimperi Moq. | chen 2590 | C4 (3) | salsoloid+H (this study) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sympegma regelii Bunge | chen 383a/2766 | C3 (4, 11) | sympegmoid (2, 9, 16, this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Salsola genistoides Juss. ex Poir. (outgroup) | chen 1155/1362 | C3 (1, 9) | sympegmoid (11, this study) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

References for C 3 versus C 4 type carbon isotope ratio: 1 = Akhani et al. (1997), 2 = Akhani and Ghasemkhani (2007), 3 = Carolin et al. (1975), 4 = Freitag and Stichler (2000), 5 = P’yankov et al. (1997), 6 = Pyankov et al. (2001), 7 = Shomer-Ilan et al. (1981), 8 = Voznesenskaya et al. (2001), 9 = Voznesenskaya et al. (2013), 10 = Wen and Zhang (2011), 11 = Wen and Zhang (2015), 12 = Winter (1981).

References for leaf anatomy: 1 = Bokhari and Wendelbo (1978), 2 = Carolin et al. (1975), 3 = Freitag and Duman (2000), 4 = Freitag et al. (1999), 5 = Freitag and Stichler (2000), 6 = Khatib (1959), 7 = Kothe-Heinrich (1993), 8 = Maire (1962), 9 = Monteil (1906), 10 = P’yankov et al. (1997), 11 = Pyankov et al. (2001), 12 = Volkens (1887), 13 = Voznesenskaya et al. (2001), 14 = Voznesenskaya et al. (2013), 15 = Wen and Zhang (2011), 16 = Wen and Zhang (2015).

*In Voznesenskaya et al. (2013) this species was mentioned to have the C4 pathway. However, samples for the carbon isotope value were taken from a wrongly identified specimen [D. Podlech 44954 (P)]. The correct identification for this specimen is Salsola oppositifolia, which indeed is a C4 species.

** C4 metabolism deduced from leaf anatomy, no carbon isotope values available.

*** Classified as sympegmoid in Freitag and Duman (2000), Pyankov et al. (2001) and Khatib (1959).

Results

Leaf anatomy

Light microscopy

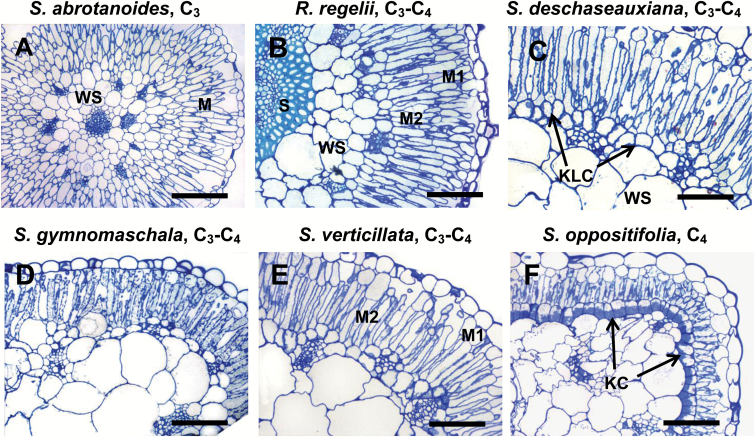

Figure 1A shows that S. abrotanoides (C3) mostly had two layers of palisade M cells. The peripheral vascular bundles (VBs) were surrounded by a layer of bundle sheath (BS) cells, which looked similar to the adjacent cells of the water-storage (WS) tissue but were smaller.

Fig. 1.

General anatomy in leaves of five Salsola species (A, C–F) and Rhaphidophyton regelii (B). Salsola abrotanoides (A), S. deschaseauxiana (C), S. gymnomaschala (D), S. verticillata (E), and S. oppositifolia (F). The images show light microscopy on leaf cross-sections illustrating the position of the palisade mesophyll (M) and bundle sheath (BS)/Kranz-like cells (KLCs)/Kranz cells (KCs). Note the continuous layer of KLCs in R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, and S. verticillata, and the difference between the outer (M1) and inner (M2) layers of mesophyll. Sclerenchyma (S) and water-storage (WS) tissue are also indicated. Scale bars = 200 μm for (A); 100 μm for (B–F).

Four species (all C3–C4), R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, and S. verticillata (Fig. 1B–E) were similar in having two layers of chlorenchyma cells underneath the epidermis. While the inner layer consisted of elongated palisade cells (M2), the cells of the outer layer (M1) were 2–5 times shorter with a reduction to varying degrees in the number of chloroplasts depending on species and growth conditions. In R. regelii the M1 cells were elongated (Figs 1B and 2), but in the other species the M1 cells appeared almost globular to polyhedral in shape; they were wider than the M2 palisade cells and more similar to the typical hypodermis of C4 species (Fig. 1C–E). These species had a clearly defined continuous (or almost continuous in R. regelii) layer of chlorenchymatous Kranz-like cells (KLCs), which was situated above and between the peripheral VBs.

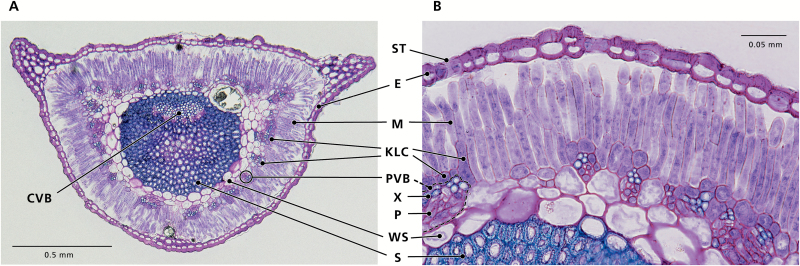

Fig. 2.

Leaf cross-sections of Rhaphidophyton regelii, a C3–C4 species with Kranz-like Salsoloid leaf anatomy. (A) Cross-section of entire leaf, and (B) close-up of the chlorenchyma. Abbreviations: E, epidermis; M, mesophyll; KLC, Kranz-like cells; WS, water storage tissue; S, sclerenchyma; CVB, central vascular bundle; PVB, peripheral vascular bundles; X, xylem; P, phloem; ST, stoma.

In S. oppositifolia (C4) the palisade M2 cells were rather short and M1 cells were represented by a typical hypodermis consisting of large globular cells that were almost devoid of chloroplasts. The KCs had organelles in a centripetal position; they formed a continuous layer just beneath the palisade cells (Fig. 1F).

Among the Salsola species in this study, C3S. abrotanoides had the lowest volume of WS tissue. In R. regelii, the inner part of the WS tissue was replaced by massive sclerenchyma tissue, which accounted for half of the leaf diameter and for the stiff appearance of the leaves (Fig. 2). Crystal-bearing idioblasts were preferentially located in the hypodermis or hypodermis-like layer, and in the Kranz-like layer between the peripheral bundles, but they could occur scattered elsewhere. In S. gymnomaschala and in S. verticillata the epidermis was partially doubled. In all Salsola species the main vein was located more or less in the center of the leaf and surrounded by 2-4 layers of WS tissue.

Transmission electron microscopy

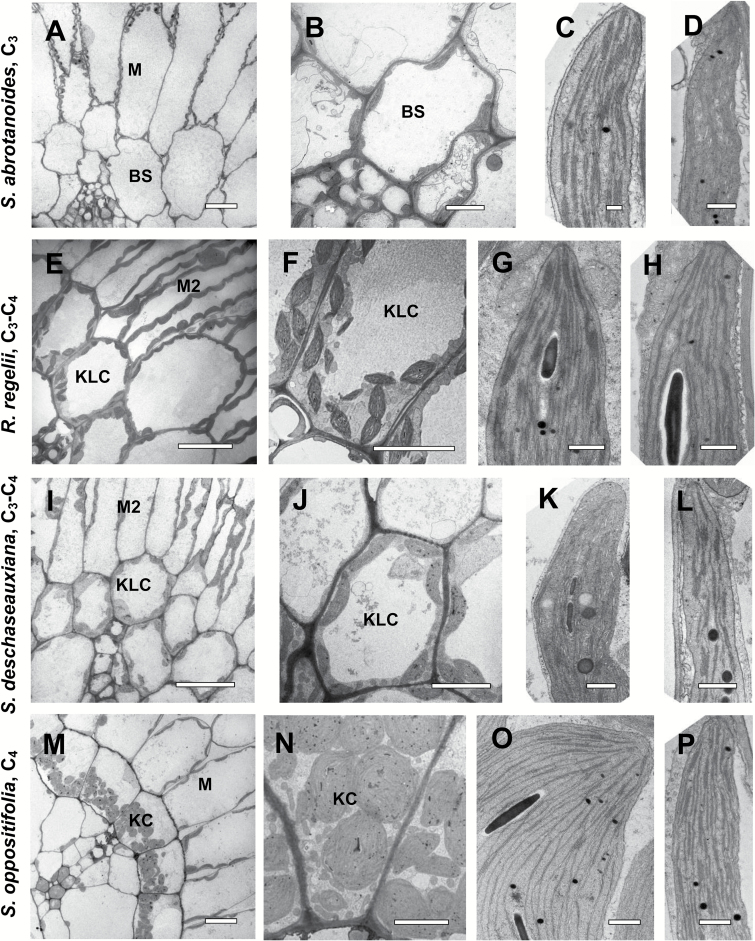

Figure 3 shows obvious differences in the quantity, position, size, and level of development of BS cell organelles in the C3 species and in the corresponding KLCs in intermediates and the KCs of the C4 species.

Fig. 3.

Electron microscopy of bundle sheath (BS)/Kranz-like cells (KLCs)/Kranz cells (KCs) and mesophyll (M) chlorenchyma cells in leaves of three Salsola species and Rhaphidophyton regelii: S. abrotanoides (A–D), R. regelii (E–H), S. deschaseauxiana (I–L), and S. oppositifolia (M–P). (A, E, I, M) Micrographs show M and BS/KLC/KC around vascular bundles. (B, F, J, N) Organelle distribution in BS/KLC/KC at a higher magnification. Note the difference in abundance of organelles in BS/KLC/KC between species, and the numerous mitochondria in KLCs of R. regelii (F) and S. deschaseauxiana (J), and in KCs in S. oppositifolia (N). (C, G, K, O) Chloroplast structure in BS/KLC/KC. (D, H, L, P) Structure of M chloroplasts. Scale bars = 20 μm for (A, I, M); 10 μm for (E,J, M); 5 μm for (N); 1 μm for (F); 0.5 μm for (B–D, G, H, K, L, O, P).

C3Salsola abrotanoides (Fig. 3A, B) had the lowest number of organelles in BS cells; a few chloroplasts and mitochondria were distributed more or less evenly along the cell wall, with some mitochondria located in a centrifugal position. The structure of the thylakoid system was similar for BS and M chloroplasts (Fig. 3C, D).

In the KLCs of four species identified as C3–C4 intermediates, R. regelii (Fig. 3E, F), S. deschaseauxiana (Fig. 3I, J), S. gymnomaschala, and S. verticillata (not shown), the chloroplasts were at least twice as numerous (per cell section) than those of the BS in S. abrotanoides; they were distributed along the cell wall but tended to be enriched in the centripetal position. The mitochondria were also twice as numerous (per cell section) and 1.5–2 times larger than in BS cells of S. abrotanoides; and most of them were located in the centripetal position, close to the inner periclinal or radial cell walls (Fig. 3F, J). KLC chloroplasts (Fig. 3G, K) and M chloroplasts (Fig. 3H, L) in R. regelii and S. deschaseauxiana (and the other two Salsola intermediates, not shown) had a similar structure with a well-developed system of medium-sized grana consisting of 7–11 thylakoids.

The KCs in C4S. oppositifolia contained numerous organelles in the centripetal position (Fig. 3M, N). The chloroplast structure differed remarkably among M cells and KCs: while the M chloroplasts had small to medium-sized grana of 2–5 thylakoids in stacks (Fig. 3P), the KC chloroplasts had numerous single thylakoids that interconnect small grana of paired thylakoids, or a few grana consisting mostly of 3–5 thylakoids (Fig. 3O).

Mitochondria in BS and M cells of S. abrotanoides had a similar size and structure (~0.4 µm), whereas in the KLCs of S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and R. regelii they were about 1.3–1.5 times larger compared to the M cells. In KCs and M cells of S. oppositifolia the mitochondria were almost identical in size (~0.5 µm).

Carbon isotope composition (δ13C) and CO2 compensation point (Г)

Of the species studied biochemically and physiologically here, S. oppositifolia had C4 δ13C values (–13.7 ‰) while the other species had δ13C values ranging from –28.8 to –31.5‰, typical for C3 plants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Carbon isotope discrimination (δ13C) and CO2 compensation point (Г) for a subset of Salsoleae s.s. Values with different letters are significantly different according to one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey HSD.

| Species | Carbon isotope discrimination δ13C, o/oo | CO2 compensation point, Г, µmol mol–1 |

|---|---|---|

| S. abrotanoides, C3 | -31.2 ± 0.6 (n = 4) a | 61.2 ± 0.7 (n = 2) a |

| R. regelii, C3–C4 | -31.5 ± 0.3 (n = 8) a | 36.1 ± 2.2 (n = 4) b |

| S. deschaseauxiana, C3–C4 | -29.9 ± 0.3 (n = 6) ab | 31.9 ± 1.8 (n = 4) b |

| S. gymnomaschala, C3–C4 | -28.8 ± 0.3 (n = 12) b | 31.2 ± 1.0 (n = 3) b |

| S. divaricata, C3–C4 | -29.9 ± 0.3 (n = 16) ab | 33.3 ± 2.5 (n = 3) b |

| S. verticillata, C3–C4 | -29.1 ± 0.4 (n = 14) b | 32.2 ± 2.0 (n = 6) b |

| S. oppositifolia, C4 | -13.0 ± 0.3 (n = 6) c | 3.7 ± 0.9 (n = 4) c |

Г was measured at 25 °С, 1000 PPFD, and 20% O2 in mature leaves of six Salsola species and R. regelii (Table 2). Г values were characteristic of C4 species for S. oppositifolia (3.7 µmol mol−1) and characteristic of C3 species for S. abrotanoides (61.2 µmol mol−1). The Г values in the other five species (R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and S. divaricata) were intermediate between C3 and C4, being about 32 µbar in the four Salsola species and 36.2 µmol mol−1 in R. regelii (Table 2).

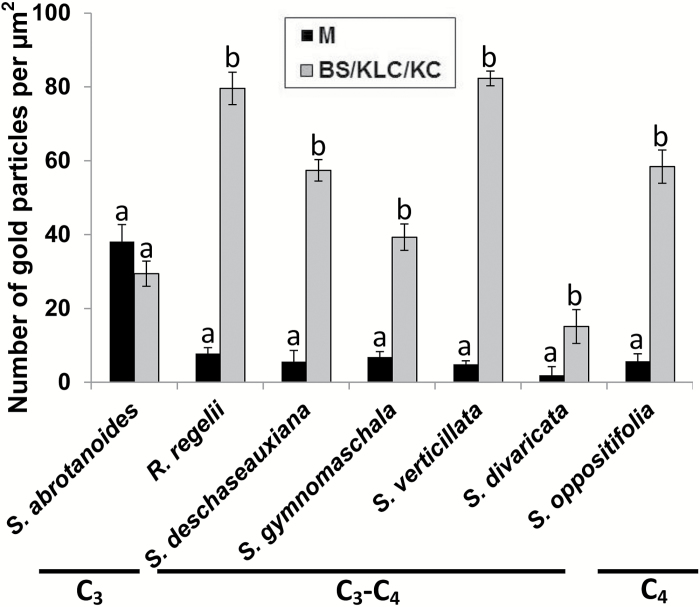

Immunolocalization of GDC

In situ immunogold labeling for GDC using the antibody to the P protein was examined by electron microscopy, and a quantitative analysis was made based on the density of gold particles, in C3S. abrotanoides, C3–C4R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, and S. verticillata, along with the C3–C4 species S. divaricata and C4S. oppositifolia. Analysis of the immunolabeling distribution showed that there was no significant difference in density of the gold particles between the mitochondria of M and BS cells in C3S. abrotanoides (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, in the C4 species S. oppositifolia gold particles were selectively localized in KC mitochondria with low labeling in M mitochondria, with a 10-fold difference in their number. In the intermediates R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, and S. verticillata, as well as in S. divaricata, the number of gold particles was also ~5.8–10 times higher in KLCs compared to M mitochondria (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Quantitative data on GDC immunolabeling in mesophyll (M) and bundle sheath (BS)/Kranz-like cells (KLC)/Kranz cells (KC) for a subset of Salsoleae. The background labeling was low and did not exceed 4.0. Different letters indicate significant differences between M and BS/KLC/KC according to Tukey’s HSD (honest significant difference) test.

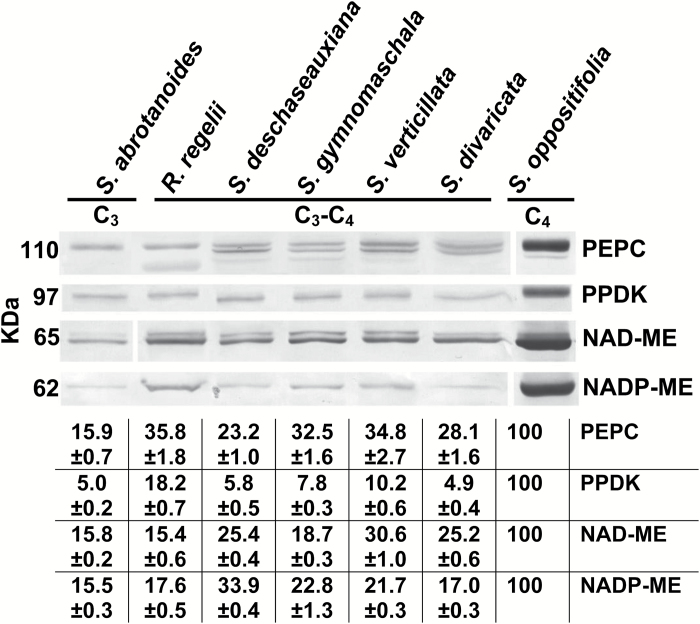

Western blot analysis of key C4 enzymes

Immunoblots for the key C4 cycle enzymes PEPC, PPDK, NAD-ME, and NADP-ME from total soluble proteins extracted from leaves of the studied species are presented in Fig. 5. The C4 species S. oppositifolia had very high labelling for the C4 pathway enzymes, PEPC and PPDK, and the two decarboxylases, NADP-ME and NAD-ME. Compared to the C4 species, the C3 species S. abrotanoides and the C3–C4 intermediates R. regelii, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and S. divaricata had very low labelling for the C4 cycle enzyme PPDK and, to varying degrees, less labelling for PEPC, NAD-ME, and NADP-ME.

Fig. 5.

Western blots for C4 enzymes from soluble proteins extracted from leaves of six Salsola s.l. species, S. abrotanoides, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, S. divaricata, S. oppositifolia, and Rhaphidophyton regelii. Blots were probed with antibodies raised against PEPC, PPDK, NAD-ME, and NADP-ME: representative western blots are presented showing detection of each protein. The originals were modified for alignment according to species; there were no selective changes in the mass or densities of bands on the membrane. The molecular mass is indicated to the left of the blots. The table gives a quantitative representation of the western blot data in percentage terms, where 100% refers to the level found in leaves of C4S. oppositifolia.

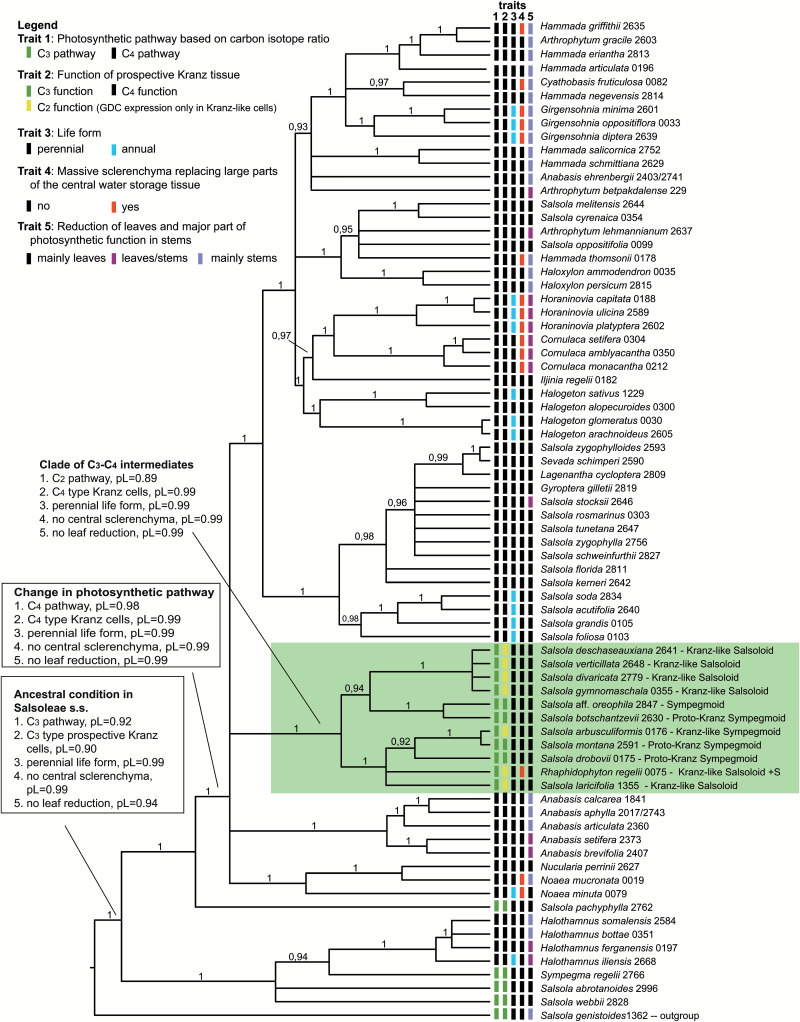

Molecular phylogeny of Salsoleae and mapping of key traits

The molecular phylogenetic analysis of the chloroplast genome revealed two unambiguous C4 lineages in Salsoleae s.s., (1) Halothamnus, and (2) Anabasis clade + Noaea clade + Haloxylon clade. Since the Anabasis clade, Noaea clade, and Haloxylon clade formed a polytomy with two C3–C4 intermediate clades, a higher number of three or four C4 origins is possible (Supplementary Fig. S3). When using a narrower outgroup (only Salsola genistoides) the two C3–C4 intermediate clades merged into a monophyletic group that still formed a polytomy with the Anabasis clade, Noaea clade, and Haloxylon clade (Fig. 6). From the crown group age of Halothamnus (7.9–1.3 mya), Anabasis (10.2–2.6 mya), and Noaea (10.3–2.8 mya) it can be assumed that in these lineages C4 photosynthesis has been present since the Late Miocene/Early Pliocene. Only for the Haloxylon clade can a distinctly older minimum age for the origin of C4 photosynthesis of 16.9–6.6 mya be inferred from the molecular dating. In the case of common ancestry of the Anabasis clade + Noaea clade + Haloxylon clade, C4 photosynthesis might date back to 19.2–7.6 mya (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Fig. 6.

Molecular phylogenetic tree of Salsoleae s.s. (Chenopodiaceae) based on four cp markers (atpB-rbcL spacer, ndhF-rpl32 spacer, trnQ-rps16 spacer, rpl16 intron) and 74 representative species. The tree was calculated using the program package BEAST (posterior probabilities are shown above branches) and was rooted with Salsola genistoides. Character optimization was conducted using Mesquite and ancestral conditions are indicated for selected nodes (pL = proportional likelihood).

The ML character optimization inferred a perennial life form and fully developed leaves without massive central sclerenchyma as the ancestral condition in Salsoleae s.s. (Fig. 6). An annual life form evolved at least six times independently in the tribe. A massive central sclerenchyma also evolved repeatedly (Fig. 6). In some cases, this feature was characteristic at the generic level, as in Girgensohnia, Horaninovia, Cornulaca, Raphidophyton, and Noaea. The reduction or complete loss of a true leaf lamina and a shift of photosynthetic function to the young stems was a common feature in Salsoleae and evolved multiple times in C4 lineages of Salsoleae s.s., but also in S. genistoides. The occurrence of leafless species was clustered in certain genera, such as Anabasis, Haloxylon, and Hammada, the latter of which seemed to be highly polyphyletic.

Furthermore, the ML character optimization inferred a C3 metabolism and C3-type BS cells as ancestral in Salsoleae s.s. According to the ancestral character state reconstruction, a switch towards C4 seems to have already occurred along the branch leading to the large sister group of the C3 species Salsola pachyphylla, which contains three C4 subclades but also one clade of C3 and C3–C4 intermediates (highlighted green in Fig. 6). This clade of C3 and C3–C4 intermediate species did not contain any C4 species, and the clade was part of a polytomy of C4 clades; thus, there is no indication in the cp tree that the C3–C4 intermediates represent ancestral states leading towards full C4 photosynthesis.

Resolution in the ITS tree was weak in many parts of the tree (Supplementary Fig. S4). Combining cp and ITS data resulted in very low resolution (tree not shown) due to conflicting topologies. Branches that were in conflict between the two data sets (with bootstrap >75) are marked on the ITS tree (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

Evidence for newly identified C3–C4 species in Salsoleae

Results from gas exchange (Γ), compartmentation of GDC between M cells and KLCs, analyses of carbon isotope composition, and analyses of levels of C4 enzymes, along with the structure of the respective cells, indicated that four species, S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and R. regelii, are C3–C4 intermediates, while S. abrotanoides operates C3 photosynthesis. Analyses of the carbon isotope composition of these four intermediates as well as the C3–C4 intermediate S. divaricata showed they all have values in the range of those of C3 species compared to the C4-type value in S. oppositifolia (Table 2). However, values for plants grown in growth chambers are more negative (i.e. up to 4–7‰) than samples from natural habitats (Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). The more positive δ13C values in the natural habitat may be due to growth under arid conditions limiting CO2 diffusion into leaves (Cerling, 1999), or to induction of a partially functional C4 cycle. According to our study, among Salsoleae there are at least 19 species with C3 isotope values, seven of which are C3–C4 species (Table 1).

Structural, biochemical, and functional analyses are needed in order to determine whether species having C3-type δ13C values are C3, proto-Kranz, or C3–C4. An important test is measurement of Γ, since values are lower in C3–C4 than in C3 plants, which is indicative of a reduction in photorespiration (Edwards and Ku, 1987). Gas exchange analyses of S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and R. regelii showed that all these species have Γ values that are intermediate between C4S. oppositifolia and C3S. abrotanoides (Table 2). Additionally, C3–C4 intermediates, like C4 species, have selective compartmentation of GDC in KLC mitochondria (Rawsthorne et al., 1988; Voznesenskaya et al., 2001, 2013; Sage et al., 2012, 2014), supporting refixation of photorespired CO2. Analysis of GDC levels by immunolocalization in these four intermediates indicated selective localization in mitochondria of Kranz-like cells (KLCs), while in the C3 species S. abrotanoides the density of immunolabeling for GDC was similar in M and BS mitochondria.

Western blot analysis of C4 enzymes showed that levels in the C3 species S. abrotanoides and the C3–C4 intermediates S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and R. regelii were very low compared to the C4 species S. oppositifolia. The levels of PEPC in the four C3–C4 intermediate species were higher than in the C3 species S. abrotanoides. However, except for R. regelii, levels of PPDK were low and barely detectable in both the C3 and intermediate species. R. regelii had higher levels of PPDK, but low levels of C4 decarboxylases similar to the C3 species.

Currrently, the results suggest that all seven known C3–C4 species of Salsoleae, R. regelii, S. arbusculiformis, S. deschaseauxiana, S. divaricata, S. gymnomaschala, S. laricifolia, and S. verticillata (Voznesenskaya et al., 2001, 2013; Wen and Zhang, 2015; this study, Table 1), are Type I, where the reduction of Г comes from refixation of photorespired CO2 in KLCs with little or no function of a C4 cycle (Edwards and Ku, 1987). Whether there is a contribution from a limited C4 cycle to photosynthesis in these intermediates could be more directly analyzed by the method of Alonso-Cantabrana and von Caemmerer (2016) via online measurements of photosynthesis and carbon isotope discrimination.

A model for evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Salsoleae based on identified photosynthetic phenotypes

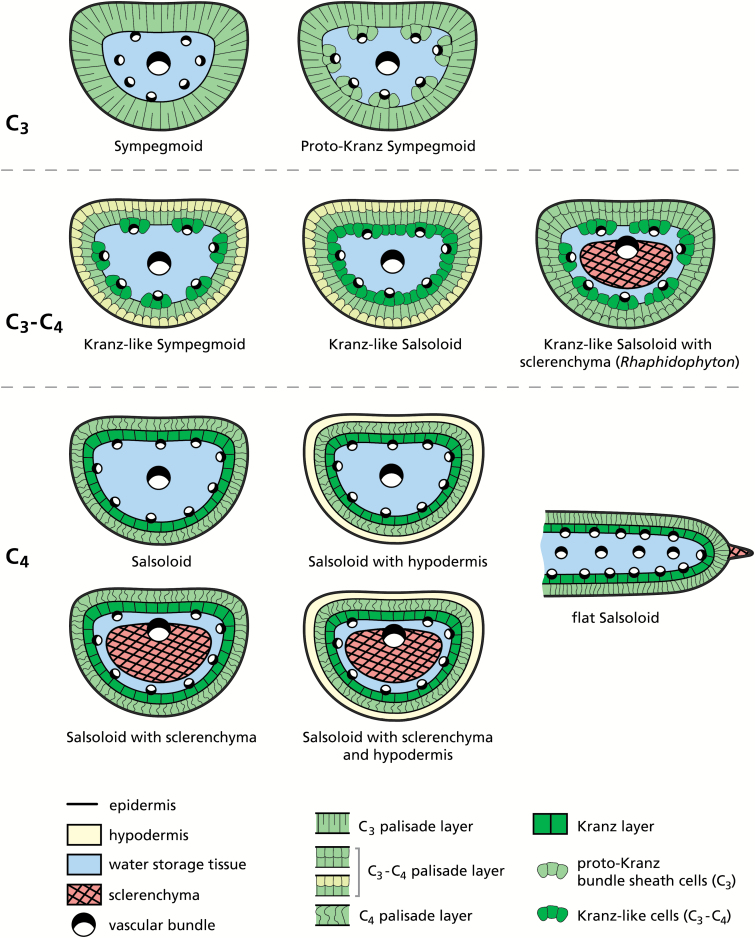

Of the 77 species of Salsoleae analyzed, without those of the Kali clade (Table 1), 24 species were studied for the first time. Our sampling was comprehensive and surpasses Carolin et al. (1975) with 43 species and Pyankov et al. (2001) with 38 species. Of the 77 species, 19 had C3-type carbon isotope composition (consisting of seven C3 species, five proposed proto-Kranz species, and seven C3–C4 intermediates) while 58 were C4 species with C4-type carbon isotope composition and Salsoloid-type leaf anatomy (Table 1). In Fig. 7 five photosynthetic phenotypes in Salsoleae are described based on the anatomical, ultrastructural, and biochemical analyses of species in the current study together with a few species described by Voznesenskaya et al. (2013). In this model, C4 is proposed to have evolved structurally and functionally from C3 Sympegmoid to Proto-Kranz Sympegmoid to C3–C4 Kranz-like Sympegmoid to C3–C4 Kranz-like Salsoloid to C4 Salsoloid-type anatomy. There are two subtypes of Kranz-like Salsoloid C3–C4 intermediates (with or without sclerenchyma) and five anatomical subtypes with Salsoloid type.

Fig. 7.

Anatomical schemes of leaf types found in Salsoleae s.s.

Non-Kranz anatomy, functionally C3

The Sympegmoid leaf type is anatomically and functionally C3. It is characterized by usually two well-developed layers of palisade M cells (M1 and M2) and indistinct C3-type BS cells around peripheral VBs containing only a few organelles. Species of this type have C3 δ13C values, C3-type Γ values, and structural features of M and BS cells characteristic of C3 plants (including the occurrence of GDC in both M and BS mitochondria). It is found in S. abrotanoides (this study, Figs. 1A, 3, 4), S. genistoides, S. oreophila, S. pachyphylla, S. webbii (Carolin et al., 1975; Voznesenskaya, 1976; P’yankov et al., 1997; Pyankov et al., 2001; Voznesenskaya et al., 2013), and Sympegma regelii (Wen and Zhang, 2011). Based on anatomical evidence alone, we conclude that Salsola tianschanica. belongs to this group, which would then comprise seven species in total (Table 1). An additional trait observed in this group is the comparatively low volume of water storage (WS) tissue and the position of peripheral VBs embedded in the WS tissue rather than at its periphery (Fig. 1A). From known data and the taxonomic literature, in particular the pertinent revisions of section Coccosalsola by Botschantzev (1976, 1989), the occurrence of this leaf type in other species is unlikely.

Proto-Kranz anatomy, functionally C3

Proto-Kranz species have anatomical changes in BS cells that may be the earliest phase of C4 evolution, preceding development of the C2 cycle (Sage et al., 2014). In Salsoleae, the Proto-Kranz Sympegmoid type only differs from the Sympegmoid type by having distinct cells with chloroplasts and mitochondria arranged preferentially along the inner and the radial walls between peripheral VBs and the chlorenchyma (Fig. 7). Currently this type is only documented in S. montana (Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). It has C3-like δ13C and Γ values, and immunolabeling for GDC is similar for M and BS mitochondria. However, based on analysis of leaf anatomy (by light microscopy of fresh leaf or herbarium samples fixed in FAA) there are additional probable candidates for proto-Kranz anatomy among the Central Asian Salsola species that have C3 δ13C values, namely S. botschantzevii, S. drobovii, S. junatovii, and S. lipschitzii (Table 1).

Kranz-like anatomy, functionally C3–C4 intermediate

Anatomically there are two types of intermediates in Salsoleae, the Kranz-like Sympegmoid type, and the Kranz-like Salsoloid type (Fig. 7). They resemble C4Salsola species in having KLCs with numerous organelles in the centripetal position. Both have C3-type δ13C values, selective localization of GDC in KLC mitochondria, and intermediate Γ values indicating functionally C2-type species.

The Kranz-like Sympegmoid type is very similar to the aforementioned Sympegmoid forms; but the outer M cells (M1) are distinctly shorter and smaller than the inner M cells (M2) and the KLCs are restricted to the peripheral VBs. This type of structure has so far only been found in S. arbusculiformis (Voznesenskaya et al., 2001), and it is suggested to represent the first functional step towards C4-type anatomy.

In the Kranz-like Salsoloid type of intermediacy, the M1 appear more like the hypodermal cells in C4 species, while still containing more or less numerous chloroplasts. M1 cell size and M/KLC ratio is reduced in comparison with the Sympegmoid types, and the KLCs form a more or less continuous layer (interrupted by crystal-containing idioblasts) around the leaf, as in C4Salsola species. The KLCs contain chloroplasts and numerous large mitochondria positioned towards the inner cell wall, characteristic of other C3–C4 intermediate species (Edwards and Ku, 1987; Rawsthorne and Bauwe, 1998; Voznesenskaya et al., 2007, 2010; Muhaidat et al., 2011; Sage et al., 2012, 2014). This type is currently found in six species (Table 1): S. laricifolia (Wen and Zhang, 2011, 2015), S. divaricata (Voznesenskaya et al., 2013), and S. deschaseauxiana, S. gymnomaschala, S. verticillata, and R. regelii (this study, Figs 1 and 7). However, R. regelii represents a different subtype by its very strong central sclerenchyma (Fig. 2), which, according to our knowledge, is unique among the C3–C4 intermediates identified in Salsoloideae.

Of note in the Kranz-like Salsoloid type, considerable variation occurs, mainly in the size, shape and the number of organelles in the M1 cell layer and the arrangement of the KLCs. Sometimes multiple sections within species revealed a certain degree of variation, showing phenotypes more similar to the Kranz-like Sympegmoid type or phenotypes approaching C4 plants with typical Salsoloid leaf anatomy. Therefore, more detailed studies are needed to assess the phenotypic plasticity of the functionally intermediate types.

Kranz-type anatomy, functionally C4

The Salsoloid leaf anatomy in C4 lineages of Salsoleae differs substantially from C4 eudicots having Atriplicoid-type leaf anatomy with Kranz anatomy around individual veins in flat leaves. Species with Salsoloid-type anatomy are functionally C4, with a continuous layer of Kranz cells (KC) around WS tissue and VBs. If the M1 layer of cells is present it occurs as a hypodermis with few or no organelles. There is a further reduction in the M/KC ratio, with organelles in the KCs in a centripetal (or, rarely, in centrifugal) position. In other lineages, as in Halothamnus, Noaea, Kali, Nanophyton, and Climacoptera, the hypodermis is lacking (Kadereit et al., 2003; Wen and Zhang, 2011). Our data on S. oppositifolia, and on several other C4 species that had not previously been studied, do not add substantially to the well-known Salsoloid-type anatomy. Together with 40 other species, S. oppositifolia displayed the most common Salsoloid type that has a hypodermis and lacks central sclerenchyma; on the other hand only 12 species account for the variant with central sclerenchyma. The Salsoloid type without a hypodermis and without central sclerenchyma was represented in our sampling by four species of Halothamnus only. This form is present in many other species of that genus (Kothe-Heinrich, 1993), and in almost all species of Kali (Rilke, 1999), while the variant with a central sclerenchyma was seen only in the two Noaea species.

Comparison with the ‘Flaveria model’ for C4 evolution

The various photosynthetic phenotypes in Salsoleae fit the general model of evolution from C3 to proto-Kranz, to intermediates, to Kranz anatomy with a progressive reduction in functional losses due to photorespiration. However, in the ‘Flaveria model’ where Kranz anatomy forms around individual veins (Edwards and Ku, 1987; Sage et al., 2012) the structural modifications are very different from the modifications from a Sympegmoid type to a Salsoloid Kranz type where the Kranz anatomy is formed around all veins and WS tissue. In evolution from C3 to C4 with Kranz anatomy around individual veins, there is increased vein density and size of BS cells around veins as they develop KC features. In contrast, in the Salsoleae the vein density in C4 species does not appear to be higher than in the C3 species. In addition, the size of the KCs is not significantly increased in the C4 species in comparison with their forerunners in C3 species (Voznesenskaya et al., 2013). Furthermore, in the Salsoleae model (see fig. 9 in Voznesenskaya et al., 2013) a decrease in the M/KC ratio might also be a precondition, as in grasses (Christin et al., 2013) and dicots (Sage et al., 2012); however, it happens by development of a continuous layer of KCs and reduction in the M1 layer rather than by an increase of veins and BS size.

Where and when did C4 photosynthesis originate in Salsoleae?

The chloroplast gene tree of Salsoloideae resolves five primary clades in the subfamily, namely the Nanophyton clade, the Caroxyloneae clade, the Salsola genistoides clade, the Kali clade, and the Salsoleae s.s. clade (Supplementary Fig. S3; Kadereit and Freitag, 2011), with the first four forming the sister group to Salsoleae s.s. (Supplementary Fig. S3). Molecular trees based on the nrDNA marker ITS (Supplementary Fig. S4) also reveal these clades but they are contradictory in their positions (for a short discussion on this matter see Supplemetary Fig. S3). According to our results in both data sets only two clearly independent C4 lineages in Salsoleae seem likely. The first lineage is Halothamnus, with a crown age of 7.9–1.3 mya, and probably plus the Kali clade in the ITS data set. Most species of both clades have Salsoloid leaf anatomy and lack a hypodermis (e.g. as in Traganum). In the cp tree the monospecific C3 genus Sympegma is sister to Halothamnus while in the ITS tree it is sister to all C3–C4 intermediates and C4 clades in the Salsoleae sensu lato (s.l., Supplementary Fig. S4). The Halothamnus and Kali clades seem to have no close relatives with a C3–C4 intermediate phenotype. The second C4 lineage in Salsoleae s.s. probably consists of all other C4 species. Since the C4 clades of Anabasis, Noaea, and Haloxylon form a polytomy with the C3–C4 intermediates clade in the cp tree (Fig. 6), one large monophyletic C4 clade and a sister-group relationship to the C3–C4 intermediates remains possible. Unfortunately, the weak resolution of this particular part of the ITS tree within Salsoleae s.s. does not support this (Supplementary Fig. S4). The overall similar Salsoloid leaf anatomy with hypodermis (except for the two species of Noaea) and NADP-ME biochemistry is in favor of common ancestry of the C4 syndrome in this lineage. The predicted age of this large C4 lineage in Salsoleae s.s. is 19.2–7.6 mya (Supplementary Fig. S3), which is in accordance with the origin of many other C4 lineages during the Middle to Late Miocene (Christin et al., 2011).

Does the C3–C4 intermediate condition represent an ancestral state to C4 in Salsoleae? Is there phylogenetic evidence for a reversion from C4 back to C3?

The ML optimization suggests that early Salsoleae were shrubs or subshrubs that performed C3 photosynthesis in well-developed leaves with a Sympegmoid leaf type (Fig. 6). Along with one C3 species (S. oreophila), 10 species (consisting of proto-Kranz and C3–C4 intermediates) in Salsoleae form one (Fig. 6) or two clades (Supplementary Fig. S3) in the cp trees. Lack of resolution in the phylogenetic trees just at the node where these phenotypes and their closest C4 relatives arise hampers a reconstruction of these proto-Kranz and C3–C4 intermediates as ancestral (see also Supplementary Fig. S4). The ML optimization even suggests that the node from which these phenotypes arise was most likely C4 (pL=0.98, Fig. 6), which would imply the origin of these C3–C4 species from C4. However, in general a reversion from C4 back to C3 or intermediate phenotypes seems to be exceedingly rare, if not improbable. Although a few cases have been reported in which C3 species or C3–C4 intermediates are nested in a C4 clade, there has also been plausible evidence for a scenario of multiple C4 origins (e.g. Ocampo et al., 2013; Bohley et al. 2015). In the case of Salsoleae s.s., we assume that a convincing reconstruction is severely hampered by the low number of C3–C4 intermediate lineages (not by the low number of intermediate species) since all C3–C4 intermediate species seem to belong to just one lineage.

This C3–C4 intermediate-rich lineage might, however, be of major interest for future studies. Studying the ecology, physiology, and biochemistry of closely related proto-Kranz and C3–C4 intermediate species with and without selective localization of GDC might provide further insights into the selective advantage of proto-Kranz anatomy and the C2 pathway. So far the selective advantage of displacement of BS organelles towards the centripetal position in proto-Kranz compared to C3 species is not clear. Possibly the proto-Kranz state leads to a slight increase in refixation of the CO2 generated by GDC in BS cells; however, this could be difficult to detect experimentally (e.g. by measurements of Γ). A C2 cycle is indeed able to generate distinctly higher CO2 levels in leaves (Keerberg et al., 2014) and therefore has an ecophysiological advantage. Since a reversion from intermediate to C3 still seems possible in this clade (S. oreophila), there is a need for further sampling and deeper resolution within this lineage.

Reduction of leaf lamina combined with photosynthesis being taken over by the green stem cortex evolved multiple times in Salsoleae; however, except for S. genistoides, this is only observed in the C4 clades. We hypothesize that the higher productivity of the C4 cycle in Salsoleae allows for a reduction in the surface area and the amount of photosynthetic tissue, reduction of transpiration, and an increase in water use efficiency. This is obviously advantageous in the extremely dry habitats of the Eurasian deserts and semi-deserts that the Salsoleae have successfully colonized.

Conclusions

In the model for evolution of C4 in Salsoleae, putative C3 ancestors have M tissue surrounding the entity of veins with a limited volume of WS tissue; differentiation occurs with development of KLCs next to minor veins, reduction in size of M cells, and ultimately development of an internal layer of KLCs that surrounds all the vascular and WS tissue. Compared to the ‘Flaveria model’ for C4 development around individual veins, in Salsoleae the proposed biochemical and functional transitions suggest convergence; however, there is obvious divergence in how structural changes were made in C3 ancestors to develop Kranz anatomy. In Salsoleae, a number of structural changes that are important in the evolution of C4 flat-leaved species are missing: individual KC size often does not increase, but KC volume increases due to the formation of the continuous layer, a decrease of the M/KC ratio occurs mainly due to the reduction of the M1 layer, and the density of venation does not change. These differences might be related to the succulent nature of Salsoleae, with an increase of the volume of WS tissue during the transition from C3 to C3–C4 intermediates and to C4 species.

The Salsoleae phylogenies unambiguously reveal all C3 species, except for S. oreophila, in basal positions, and both the C4 species and the C3–C4 intermediates as derived, but occurring in different clades. Intermediates, proto-Kranz, and one C3 species are clustered in one (cp tree) or four (ITS tree) monophyletic groups that might either be sister to a large C4 clade or nested within it. In the absence of closely related C4 species, their intermediacy cannot be determined as ancestral; although they display logical stepwise, ‘model-conforming’ phenotypes from C3 to C4 photosynthesis. From a phylogenetic point of view, they may represent an evolutionarily independent solution, enabling the respective species to survive in harsh environments, even in competition with distantly related species of the same tribe possessing full C4 photosynthesis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online

Table S1. Details of the specimens of Salsoleae and outgroups included in the molecular analyses.

Table S2. Sampling of primary clades of Salsoloideae (Salsoleae, Caroxyloneae, Nanophyton clade, Salsola kali clade and Salsola genistoides clade).

Table S3. Primers, PCR recipes and cycler programs.

Fig. S1. Representative membrane stained with Ponceau S after transfer of proteins to a nitrocellulose membrane and before immunoblotting.

Fig. S2. Electron microscopy of in situ immunolocalization of GDC in chlorenchyma cells of Salsola abrotanoides (C3),

Rhaphidophyton regelii (C3–C4), S. verticillata (C3–C4), and S. oppositifolia (C4).

Fig. S3. Dated molecular phylogenetic tree of Salsoloideae (Chenopodiaceae) based on four cp markers (atpB-rbcL spacer, ndhF-rpl32 spacer, trnQ-rps16 spacer, rpl16 intron).

Fig. S4: ML tree based on ITS sequences of Salsoleae and Caroxyloneae with representatives of Salicornioideae and Suaedoideae as the outgroup.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under funds MCB #1146928 to GEE, EV, NK; partly by the Russian Foundation of Basic Research under grants 12-04-00721 and 15-04-03665 for EV, NK; and by the German Science Foundation (DFG; grant KA1816/7-1 to GK). We are grateful to the Core Facility Center ‘Cell and Molecular Technologies in Plant Science’ of Komarov Botanical Institute (St Petersburg, Russia) and Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center of Washington State University for use of their facilities and staff assistance, and to C. Cody for plant growth management. We thank D. Franke (Mainz) for help with the illustrations and C. Wild (Mainz) for curating the chenopod living collection at Mainz Botanical Garden.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BS

bundle sheath in C3 species

- Г

CO2 compensation point

- GDC

glycine decarboxylase

- KC

Kranz cell (for C4 species)

- KLC

Kranz-like cell (for C3–C4 intermediate phenotypes)

- M

mesophyll

- ML

maximum likelihood

- NAD-ME

NAD-malic enzyme

- NADP-ME

NADP-malic enzyme

- PEPC

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase

- PPDK

pyruvate, Pi dikinase

- VB

vascular bundle

- WS

water storage.

References

- Akhani H, Edwards G, Roalson EH. 2007. Diversification of the Old World Salsoleae s.l. (Chenopodiaceae): Molecular phylogenetic analysis of nuclear and chloroplast data sets and a revised classification. International Journal of Plant Sciences 168, 931–956. [Google Scholar]

- Akhani H, Ghasemkhani M. 2007. Diversity of photosynthetic organs in Chenopodiaceae from Golestan National Park (NE Iran) based on carbon isotope composition and anatomy of leaves and cotyledons. Nova Hedwigia Beiheft 131, 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Akhani H, Trimborn P, Ziegler H. 1997. Photosynthetic pathways in Chenopodiaceae from Africa, Asia and Europe with their ecological, phytogeographical and taxonomical importance. Plant Systematics and Evolution 206, 187–221. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Cantabrana H, von Caemmerer S. 2016. Carbon isotope discrimination as a diagnostic tool for C4 photosynthesis in C3–C4 intermediate species. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 3109–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender MM, Rouhani I, Vines HM, Black CC., Jr 1973. 13C/12C ratio changes in Crassulacean Acid Metabolism plants. Plant Physiology 52, 427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohley K, Joos O, Hartmann H, Sage R, Liede-Schumann S, Kadereit G. 2015. Phylogeny of Sesuvioideae (Aizoaceae) – Biogeography, leaf anatomy and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 17, 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bokhari MH, Wendelbo P. 1978. On anatomy, adaptions to xerophytism and taxonomy of Anabasis inclusive Esfandiaria (Chenopodiaceae). Botaniska Notiser 131, 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Botschantzev VP. 1976. Conspectus specierum sectionis Coccosalsola Fenzl generis Salsola L. Novosti Sistematiki Vysshikh rastenii, 13, 74–102 [in Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- Botschantzev VP. 1989. De genere Darniella Maire et Weiller et relationes ejus ad genus Salsola L. (Chenopodiaceae). Novosti Sistematiki Vysshikh Rastenii 26, 79–90 [In Russian]. [Google Scholar]

- Brown WV. 1975. Variations in anatomy, associations, and origin of Kranz tissue. American Journal of Botany 62, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Carolin R, Jacobs S, Vesk M. 1975. Leaf structure in Chenopodiaceae. Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie 95, 226–255. [Google Scholar]

- Cerling TE. 1999. Paleorecords of C4 plants and ecosystems. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, eds. C4plant biology.New York: Academic Press, 445–469. [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Osborne CP, Sage RF, Arakaki M, Edwards EJ. 2011. C4 eudicots are not younger than C4 monocots. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 3171–3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christin PA, Osborne CP, Chatelet DS, Columbus JT, Besnard G, Hodkinson TR, Garrison LM, Vorontsova MS, Edwards EJ. 2013. Anatomical enablers and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in grasses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 1381–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Ho SYW., Phillips MJ., Rambaut A. 2006. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLOS Biology 4, e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7, 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Ku MS. 1987. Biochemistry of C3–C4 intermediates. The Biochemistry of Plants 10, 275–325. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards GE, Voznesenskaya EV. 2011. C4 photosynthesis: Kranz forms and single-cell C4 in terrestrial plants. In: Raghavendra AS, Sage RF, eds. C4 photosynthesis and related CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Dordrecht: Springer, 29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AE, McDade LA, Kiel CA, Khoshravesh R, Johnson MA, Stata M, Sage TL, Sage RF. 2015. Evolutionary history of Blepharis (Acanthaceae) and the origin of C4 photosynthesis in section Acanthodium. International Journal of Plant Sciences 176, 770–790. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag H, Duman H. 2000. An unexpected new taxon of Salsola from Turkey. Edinburgh Journal of Botany 57, 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag H, Stichler W. 2000. A remarkable new leaf type with unusual photosynthetic tissue in a Central Asiatic genus of Chenopodiaceae. Plant Biology 2, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag H, Vural M, Adigüzel N. 1999. A remarkable new Salsola and some new records of Chenopodiaceae from Central Anatolia, Turkey. Willdenowia 29, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gowik U, Westhoff P. 2011. The path from C3 to C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 155, 56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock L, Edwards EJ. 2014. Phylogeny and the inference of evolutionary trajectories. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3491–3498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd JM, Covshoff S. 2010. The regulation of gene expression required for C4 photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology 61, 181–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit G, Ackerly D, Pirie MD. 2012. A broader model for C4 photosynthesis evolution in plants inferred from the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae s.s.). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 279, 3304–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit G, Borsch T, Weising K, Freitag H. 2003. Phylogeny of Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. International Journal of Plant Sciences 164, 959–986. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit G, Freitag H. 2011. Molecular phylogeny of Camphorosmeae (Camphorosmoideae, Chenopodiaceae): implications for biogeography, evolution of C4-photosynthesis and taxonomy. Taxon 60, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit G, Lauterbach M, Pirie MD, Arafeh R, Freitag H. 2014. When do different C4 leaf anatomies indicate independent C4 origins? Parallel evolution of C4 leaf types in Camphorosmeae (Chenopodiaceae). Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3499–3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keerberg O, Pärnik T, Ivanova H, Bassüner B, Bauwe H. 2014. C2 photosynthesis generates about 3-fold elevated leaf CO2 levels in the C3–C4 intermediate species Flaveria pubescens.Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3649–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]