Phyllogen, a bacterial virulence factor, induced phyllody in various eudicot species, and had broad-spectrum degradation activity on MADS domain transcription factors of plants, suggesting phyllogen universally functions in plants.

Keywords: ABCE model, floral development, MADS domain transcription factor, phyllody, phyllogen, phytoplasma

Abstract

ABCE-class MADS domain transcription factors (MTFs) are key regulators of floral organ development in angiosperms. Aberrant expression of these genes can result in abnormal floral traits such as phyllody. Phyllogen is a virulence factor conserved in phytoplasmas, plant pathogenic bacteria of the class Mollicutes. It triggers phyllody in Arabidopsis thaliana by inducing degradation of A- and E-class MTFs. However, it is still unknown whether phyllogen can induce phyllody in plants other than A. thaliana, although phytoplasma-associated phyllody symptoms are observed in a broad range of angiosperms. In this study, phyllogen was shown to cause phyllody phenotypes in several eudicot species belonging to three different families. Moreover, phyllogen can interact with MTFs of not only angiosperm species including eudicots and monocots but also gymnosperms and a fern, and induce their degradation. These results suggest that phyllogen induces phyllody in angiosperms and inhibits MTF function in diverse plant species.

Introduction

Flowers exhibit a wide variety of shapes and colors, and sometimes have abnormal phenotypes (Meyer, 1966), including phyllody (replacement of floral organs by leaf-like structures) and double flowers (flowers with extra petals or petal-like structures). Plants with such abnormal flower phenotypes have often been used as commercial cultivars (Kanno, 2016) and genetic resources to study molecular mechanisms of floral development (Meyerowitz et al., 1989; Wellmer et al., 2014). In model eudicots such as Arabidopsis thaliana, the identity of floral organs is regulated by floral homeotic genes divided into ABCE-classes based on function (the ABCE-model): A- and E-class genes specify sepal identity; A-, B-, and E-class genes petal identity; B-, C-, and E-class genes stamen identity; and C- and E-class genes carpel identity (Krizek and Fletcher, 2005; Soltis et al., 2007; Rijpkema et al., 2010). ABCE-class genes mostly encode type II MADS domain transcription factors (MTFs), which are thought to form quaternary complexes in each floral organ (the floral quartet model; Honma and Goto, 2001; Theißen et al., 2016). Homologs of ABCE-class genes are often found in angiosperms (Zahn et al., 2005a, b; Shan et al., 2007; Dreni and Kater, 2014), and the functions of B-, C-, and E-class MTFs are thought to be conserved (Cui et al., 2010; Heijmans et al., 2012b; Wang et al., 2015). Thus, the ABCE model is considered to be applicable in diverse angiosperms, especially core eudicots (Soltis et al., 2007), although differences between plant species have been observed (Rijpkema et al., 2010; Yoshida and Nagato, 2011; Teixeira da Silva et al., 2014).

Aberrant expression of the MTFs can alter floral organ identity and morphology, and result in the production of abnormal flowers in many plant species. For example, gene knockdown or knockout of C-class MTFs leads to the development of petal-like stamens in model plants, such as A. thaliana, petunia (Petunia×hybrida), and Antirrhinum majus (Yanofsky, 1990; Bradley et al., 1993; Heijmans et al., 2012a). Other reports have also shown that down-regulation of E-class MTFs leads to the replacement of all or partial flower organs by leaf-like structures in A. thaliana, petunia, and rice (Angenent et al., 1994; Pelaz et al., 2000; Vandenbussche et al., 2003; Ditta et al., 2004; Cui et al., 2010). Additionally, it has been reported that MTF genes are aberrantly expressed in several horticultural varieties with unique flower characteristics (Sun et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2016).

Phytoplasmas (‘Candidatus Phytoplasma’ spp.) are phloem-limited plant pathogenic bacteria that infect hundreds of plant species. They are capable of inducing various symptoms, including abnormal development of flowers such as phyllody, virescence (green coloration of floral organs), and a loss of floral meristem determinacy (production of stem-like pistils) (Lee et al., 2000; Arashida et al., 2008; Chaturvedi et al., 2010; Maejima et al., 2014b). Such flower malformations associated with phytoplasmas are widely observed in both eudicot and monocot species (Chaturvedi et al., 2010), and sometimes considered very attractive and valuable (Wang and Maramorosch, 1988; Strauss, 2009). Recently, it was shown that a family of highly conserved phytoplasma virulence factors, designated as a phyllody-inducing gene (phyllogen) family, induces phyllody and other floral malformation in A. thaliana (MacLean et al., 2011; Maejima et al., 2014a; Yang et al., 2015). PHYL1OY, a phyllogen from the ‘Ca. P. asteris’ onion yellows strain (OY), interacts directly with APETALA1 (AP1) and SEPALLATA1 (SEP1)–SEP4 (A- and E-class MTFs, respectively) of A. thaliana (Maejima et al., 2014a, 2015), and induces their degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner (Maejima et al., 2014a). Another phyllogen, SAP54, was also reported to bind to and induce degradation of A- and E-class MTFs, but it did not bind to APETALA3 (AP3) and PISTILLATA (PI; B-class MTFs), or to AGAMOUS (AG; C-class MTF; MacLean et al. 2014). Therefore, phyllogen-mediated degradation of the A- and E-class MTFs is regarded as the molecular mechanism responsible for phyllody symptoms in A. thaliana plants associated with phytoplasma infection. Considering that phyllody symptoms are often observed in angiosperms infected by phytoplasmas, it is interesting to verify whether phyllogen could induce phyllody in diverse plant species by mediating degradation of MTFs, as is the case in A. thaliana.

In this study, phyllogen was expressed in several plant species known to show phyllody symptoms in response to phytoplasma infection; petunia (Himeno et al., 2011; Faghihi et al., 2014), sunflower (Guzmán et al., 2014), aster (Sinha and Paliwal, 1969), and sesame (Akhtar et al., 2009). Furthermore, it was examined whether phyllogen targets A- and E-class MTFs and their homologous MTFs from diverse plant species. The results indicate that phyllogen can inhibit MTF function in angiosperms and, surprisingly, also in gymnosperms and ferns, functioning as a broad-spectrum virulence factor manipulating floral morphology.

Materials and methods

Materials

Petunia (cv. Vakara White; Sakata Seed, http://www.sakata.com), Nicotiana benthamiana, sunflower (Helianthus annuus cv. Big Smile; Takii Seed, http://www.takii.co.jp), China aster (Callistephus chinensis cv. Nene White Imp; Takii Seed), and sesame (Sesamum indicum cv. Gomao; Takii Seed) were used. The plants were grown from seed under natural light conditions at 25 °C.

Among the MTF genes shown in Table 1, SEP3 was cloned in a previous study (Maejima et al., 2014a), and the ORFs of the other MTF genes used in the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) reporter assays were synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific (https://www.thermofisher.com). The synthesized sequences lacked stop codons, but had additional sequences: 5'-AAGGAACCAATTCAGTC-3' at their 5' end and 5'-TATCTAGACCCAGCTT-3' at their 3' end. The synthesized LMADS3 and CRM6 gene sequences additionally lacked the codons for several N-terminal amino acids, because the corresponding nucleotide sequence was not available in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). The LMADS6 gene was synthesized with codon optimization because of the difficulty of synthesis (Supplementary Fig. S1A at JXB online).

Table 1.

Plant genes used in this study

| Gene | Plant | Family | Division | Class/function | Purpose | Reference | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEP3 | A. thaliana | Brassicaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | E | Y2H, reporter assay | Pelaz et al. (2000) | NM_102272 |

| PFG | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Aa | Y2H, YFP reporter assay, qRT-PCR | Immink et al. (1999) | AF176782 |

| FBP29 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Aa | qRT-PCR | Immink et al. (2003) | AF335245 |

| PhAP2A b | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Aa | qRT-PCR | Maes et al. (2001) | AF132001 |

| GLO1 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | B | qRT-PCR | Vandenbussche et al. (2004) | AY532265 |

| DEF | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | B | qRT-PCR | van der Krol et al. (1993) | DQ539416 |

| FBP6 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | C | qRT-PCR | Kater et al. (1998) | X68675 |

| pMADS3 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | C | qRT-PCR | Tsuchimoto et al. (1993) | X72912 |

| FBP2 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | E | Y2H, YFP reporter assay, qRT-PCR | Ferrario et al. (2003) | M91666 |

| FBP5 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | E | qRT-PCR | Immink et al. (2002) | AF335235 |

| FBP13 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Flowering time genec | qRT-PCR | Immink et al. (2003) | AF335237 |

| FBP25 | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Flowering time genec | qRT-PCR | Immink et al. (2003) | AF335243 |

| UNS | P. hybrida | Solanaceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | Flowering time gene | qRT-PCR | Ferrario et al. (2004) | AF335238 |

| CDM111 | C. morifolium | Asteraceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | A | Y2H, reporter assay | Shchennikova et al. (2004) | AY173054 |

| CDM44 | C. morifolium | Asteraceae | Angiospermae (eudicot) | E | Y2H, reporter assay | Shchennikova et al. (2004) | AY173057 |

| OsMADS14 | O. sativa | Poaceae | Angiospermae (monocot) | Aa | Y2H, reporter assay | Jeon et al. (2000) | AF058697 |

| OsMADS8 | O. sativa | Poaceae | Angiospermae (monocot) | E | Y2H, reporter assay | Cui et al. (2010) | U78892 |

| LMADS6 d | L. longiflorum | Liliaceae | Angiospermae (monocot) | A | Y2H, reporter assay | Chen et al. (2008) | HQ149332 |

| LMADS3 e | L. longiflorum | Liliaceae | Angiospermae (monocot) | Ef | Y2H, reporter assay | Tzeng et al. (2003) | AY826062 |

| CjMADS14 | C. japonica | Cupressaceae | Gymnospermae | Unknown | Y2H, reporter assay | Futamura et al. (2008) | AB359029 |

| DAL1 | P. abies | Pinaceae | Gymnospermae | Unknown | Y2H, reporter assay | Carlsbecker et al. (2004) | X80902 |

| CRM6 e | C. pteridoides | Pteridaceae | Pteridophyta | Unknown | Y2H, reporter assay | Münster et al. (1997) | Y08242 |

a Genes belonging phyllogenetically to A-class, but with undetermined functions.

b Gene encodes a non-MTF protein.

c Putative homolog of AGL24, a flowering time gene of A. thaliana, but with undetermined functions.

d Gene was used with codon optimization.

e Partial gene sequence was used.

f Gene belonging phyllogenetically to E-class, but with undetermined functions.

Two phyllogens were used in this study: PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB. PHYL1PnWB was isolated from peanut witches’ broom (PnWB) phytoplasma (Chung et al., 2013) and induced phyllody in A. thaliana (Yang et al., 2015). The PHYL1OY gene was cloned in a previous study (Maejima et al., 2014a). A plant codon-optimized PHYL1PnWB gene was also synthesized, as well as the MTFs, with a stop codon (Supplementary Fig. S1B). The synthesized genes were cloned into the pENTA vector (Himeno et al., 2010) digested by SalI-HF and EcoRV-HF (NEB; https://www.neb.com), using the GeneArt Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (Invitrogen; http://www.thermofisher.com), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Virus vector construction

To express phyllogen in a wide range of plants, each of the phyllogens were cloned into the Apple latent spherical virus (ALSV) vector system, which can express foreign proteins in many plant species (Li et al., 2004; Yamagishi et al., 2011). DNA fragments harboring the 35S promoter and viral cDNAs of pEALSR1 and pEALSR2L5R5 (Li et al., 2004) were cloned into the EcoRI and PmaCI sites of pCAMBIA1301, an Agrobacterium binary vector, using the GeneArt Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (pCAM-ALSV1 and pCAM-ALSR2L5R5, respectively). The multiple cloning sites (MCSs) of ALSV-RNA2 in pCAM-ALSR2L5R5 (XhoI, SmaI, and BamHI) were replaced with 5'-GTCGACCCTAGGAGCGCTGGATCC-3' (SalI, BlnI, Aor51HI, and BamHI; designated pCAM-ALSV2), because two XhoI sites and one SmaI site were also present outside of the MCS of the pCAM-ALSR2L5R5 vector.

To construct pCAM-ALSV2, the new MCS was added at one end of an amplicon by a PCR, using 1301ALSV-newRest-F and 1301ALSV-newRest-R primers (Supplementary Table S1) and the ALSV-RNA2 cDNA template. The amplicon was inserted into the SacI and BamHI sites of the pCAM-ALSR2L5R5 vector by replacing the corresponding region. Furthermore, synonymous nucleotide substitutions were introduced in the vicinity of the duplicated cleavage site, just before the MCS, as follows: 5'-TTGTTGGAGGGACAAGGACCAGACTTTACT-3' (mutated sites are underlined; designated pCAM-ALSV2opt), to improve the stability of foreign genes in the virus vector. To construct pCAM-ALSV2opt, the synthesized DNA fragment with synonymous nucleotide substitutions was added at one end of an amplicon by PCR, using 1301ALSV-newRest-F and ALSV-NewCodon-R primers (Supplementary Table S1), and the ALSV-RNA2 cDNA template. The amplicon was inserted into the SacI and SalI sites of pCAM-ALSV2 by replacing the corresponding region. PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB genes were inserted into the SalI and BamHI sites of pCAM-ALSV2opt. pCAM-ALSV1 and pCAM-ALSV2opt, carrying no gene or either of the PHYL1 genes, were used to transform the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105.

ALSV infiltration and detection

Agrobacterium cells containing ALSV-RNA1, each of the ALSV-RNA2 constructs, and a viral silencing suppressor P19, were adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0, and mixed at a ratio of 10:10:1, as described previously (Senshu et al., 2009). They were co-infiltrated into 3-week-old petunia and N. benthamiana leaves, 2-week-old sunflower leaves, and 4-week-old China aster and sesame leaves. Inoculated plants were grown under a constant photoperiod (18 h light/6 h dark) at 25 °C.

Virus infection and foreign gene retention were confirmed by a two-step reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR). Total RNA was extracted from plants ~30 d after inoculation, using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Chang et al., 1993) with minor modifications. Reverse transcription was performed as described previously (Minato et al., 2014b). PCR was performed using KOD FX (Toyobo, http://www.toyobo.co.jp) and the primers 2600F and 3000R (Supplementary Table S1), which amplify a part of ALSV-RNA2, including the MCS region.

Y2H assay

The Matchmaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 kit (Clontech; http://www.clontech.com) was used for Y2H assays, as described previously (Yamaji et al., 2006). The BD-fused PHYL1OY and AD-fused SEP3 were constructed as previously reported (Maejima et al., 2014a). For construction of the other AD-fused MTFs, the MTFs were amplified using the primers shown in Supplementary Table S1, and cloned into the pGADT7 vector (Clontech) digested by NdeI and EcoRI-HF (NEB), as described above. The BD-fused PHYL1PnWB was constructed in the same manner, using the pGBKT7 vector (Clontech), digested by NdeI and EcoRI-HF.

Lithium acetate-treated yeast cells (strain AH109) were co-transformed with pairs of appropriate pGADT7 and pGBKT7 vectors. Successful co-transformants were selected on synthetically defined medium (SD) lacking tryptophan and leucine (SD/–LW). To evaluate the protein interaction, the co-transformants were cultured on three selective media: leucine/tryptophan/histidine-lacking SD (SD/–LWH), SD/–LWH containing 5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Sigma-Aldrich) (SD/–LWH+3AT), and leucine/tryptophan/adenine/histidine-lacking SD (SD/–LWAH).

Fluorescence microscopy

Constructs for the in planta expression of PHYL1OY, β-glucuronidase (GUS), YFP-fused bZIP63, or YFP-fused SEP3 were produced in a previous study (Maejima et al., 2014a). Constructs for the expression of the other YFP-fused MTFs were obtained from pENTA carrying the MTFs and pEarleyGate101 binary vector (Earley et al., 2006), using Gateway technology (Invitrogen). Protein expression, involving fluorescence observation in N. benthamiana leaves, was performed as described previously (Maejima et al., 2014a). The number of fluorescent nuclei in a leaf area of 2.4 mm2 was quantified using Image J ver. 10.2 software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). The experiments were repeated independently three times.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

A construct for transient expression of PHYL1PnWB was produced from pENTA carrying PHYL1PnWB and the pFAST-G02 binary vector (Shimada et al., 2010), using Gateway technology. Agrobacterium cells carrying SEP3–YFP and either PHYL1PnWB or GUS constructs were co-infiltrated at a ratio of 1:1 into N. benthamiana leaves (4 weeks old) as described above. The leaves were collected 36 h after infiltration and pulverized in liquid nitrogen. Total protein was extracted with SDS sample buffer containing 5% 3-mercapto-1,2-propanediol. The extract was centrifuged at 15 000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris, and the supernatant was incubated for 5 min at 95 °C. The proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE, blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and detected using an anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (#1814460, Roche; http://www.roche.com). An immunoblotting assay of PHYL1OY was performed using Agrobacterium cells carrying YFP-fused proteins and either PHYL1OY or GUS constructs mixed in a ratio of 1:10. The experiments were repeated independently twice.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from buds (<5 mm in diameter) of ALSV-PHYL1OY- or ALSV-empty-infected petunia plants, after confirming flower malformations in the ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected plants. Nine plants per ALSV construct were used. RNA extraction, purification, and reverse transcription were performed according to a previous report (Himeno et al., 2011). A total of 500 ng of total RNA was used for reverse transcription. A qRT-PCR assay was performed using the Thermal Cycler Dice real-time PCR system (TaKaRa; http://www.takara-bio.co.jp) with SYBR Premix ExTaq (TaKaRa). A 2 µL aliquot of each 10-fold diluted cDNA was used as a template. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene was used for normalization, according to a previous report (Rijpkema et al., 2006b; Himeno et al., 2011). The primers used for qRT-PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S1. The PCR was repeated three times for each gene.

Results

Induction of phyllody phenotypes by PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB in solanaceous plants

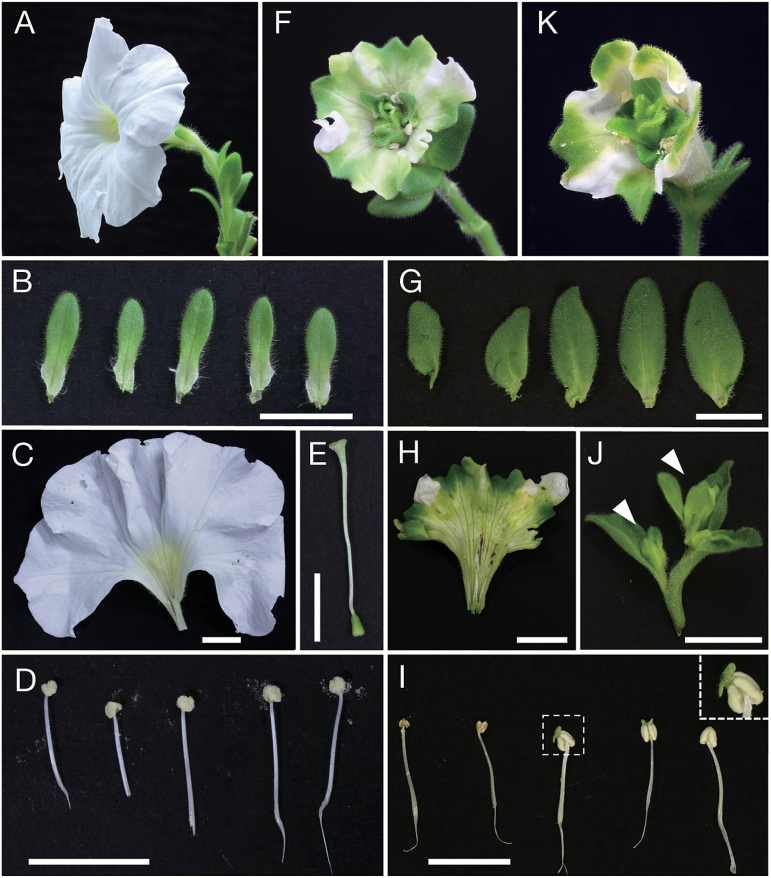

Two phyllogens (PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB) were initially expressed in petunia, a model solanaceous plant for genetic studies of floral organ development. Before the experiment, it was confirmed that PHYL1PnWB interacted with SEP3 in yeast cells and induced its degradation in planta (Supplementary Fig. S2). Each phyllogen was expressed in petunia plants using ALSV. The constructed vectors (ALSV-PHYL1OY and ALSV-PHYL1PnWB) and the ALSV-empty vector were introduced into Agrobacterium and inoculated into petunia plants. Successful infection of these plants was confirmed by RT–PCR (data not shown). At 40–60 d after inoculation, petunia plants infected with ALSV-PHYL1OY showed phyllody phenotypes (Fig. 1F–J), while those infected with the ALSV-empty vector produced normal flowers (Fig. 1A–E). All floral organs in ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected petunia plants were affected. Sepals became large, and were converted into a leaf-like, round shape (Fig. 1G). Petals became green, especially at the tips and edges of the limbs, and their size was reduced (Fig. 1H). Stamens occasionally had no pollen, and small leaf-like structures were formed on top of the anthers (Fig. 1I). In the development of pistils, leaf-like structures with trichomes replaced normal ovules, and new inflorescences with floral buds developed (Fig. 1J). ALSV-PHYL1PnWB also caused phyllody phenotypes in petunia, in a similar manner to ALSV-PHYL1OY (Fig. 1K).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of phyllogen-induced phyllody in petunia flowers. Whole flower (A) and each of the floral organs (B–E) of ALSV-empty-infected plants: (B) sepals, (C) petals, (D) stamens, and (E) a pistil. No malformation was observed in any floral organ. Whole flower (F) and each of the floral organs (G–J) of ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected plants. Flower malformations were observed in each floral organ. (G) Sepals showing leaf-like round shapes. (H) Petals becoming small and green at the tips and edges of the limbs. (I) Stamens with no pollen, but with small leaf-like structures on top of their anthers. Two left stamens did not show malformation, but pollen was already shed. An enlarged view of an abnormal anther (dotted square) is shown in the upper right of the picture. (J) Pistil replaced by leaf-like structures with trichomes. Arrowheads indicate newly developed floral buds. (K) Flower of ALSV-PHYL1PnWB-infected petunia. The observed phyllody was very similar to that of ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected petunia plants. Bars indicate 1 cm.

PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB also affected flower morphology in another solanaceous plant, N. benthamiana (Supplementary Fig. S3). In ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected N. benthamiana, the sepals were initially enlarged (Supplementary Fig. S3B), and the pistils turned into leaf-like structures (Supplementary Fig. S3C). Then the flowers developed small, greenish, and fused petals (Supplementary Fig. S3D). In later flowers, all floral organs were converted into leaf-like structures as in phyllody (Supplementary Fig. S3E). ALSV-PHYL1PnWB caused flower malformations very similar to those caused by ALSV-PHYL1OY (Supplementary Fig. S3F).

PHYL1PnWB induces phyllody in various plant species

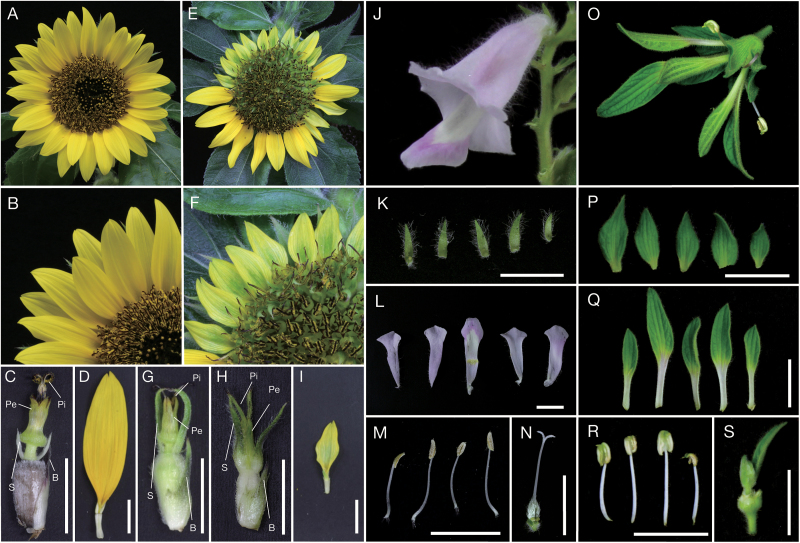

ALSV-PHYL1 was inoculated to sunflower (family Asteraceae), China aster (family Asteraceae), and sesame (family Pedaliaceae). Because the inserted sequence of the PHYL1OY gene was less stable in the ALSV viral vector compared with that of PHYL1PnWB in sunflower (data not shown), ALSV-PHYL1PnWB was used in this experiment. While ALSV-empty-infected sunflowers developed normal flowers (Fig. 2A–D), ALSV-PHYL1PnWB-infected sunflowers showed flower malformations (Fig. 2E–I). Specifically, bracts and sepals of disc florets were changed into green organs, and sepals were elongated (Fig. 2G). In severely affected disc florets, petals became green, and pistils changed into leaf-like structures (Fig. 2H). In ray florets, the size of the corolla was occasionally reduced and the color changed slightly to green (Fig. 2I). ALSV-PHYL1PnWB-infected China asters also exhibited similar flower malformations (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

Characteristics of PHYL1PnWB-induced phyllody on sunflower and sesame flowers. (A–D) Flowers of ALSV-empty-infected sunflower. A disc floret and ray floret are shown in (C) and (D), respectively. No flower malformation was observed in any floral organ. (E–I) Flowers of ALSV-PHYL1PnWB-infected sunflower. Flower malformations were observed on both disk and ray florets. (G) Disk floret showing mild malformations. Bract and sepals became green and elongated. (H) Disk floret showing severe malformations. Petals became green and a pistil changed into a leaf-like structure. (I) Ray floret showing malformations. Corolla became small, and its color changed slightly to green. (J–S) Characteristics of phyllogen-induced phyllody in sesame flowers. Whole flower (J) and each of the floral organs (K–N) of ALSV-empty-infected sesame plants: (K) sepals, (L) separated petals, (M) stamens, and (N) a pistil. No malformation was observed in any floral organ. Whole flower (O) and each of the floral organs (P–S) of ALSV-PHYL1PnWB-infected plants. Flower malformations were observed in each floral organ. (P) Sepals showing large leaf-like structures. (Q) Petals becoming green from the tips. (R) Stamens with no pollen, but with small leaf-like structures on top of their anthers. (S) Pistils replaced by leaf-like structures. Bars indicate 1 cm. B, bracts; S, sepals; Pe, petals; Pi, pistils.

PHYL1PnWB expression resulted in phyllody phenotypes in all floral organs of sesame (Fig. 2J–S), in a manner very similar to that observed in petunia. Sepals were converted into large leaf-like structures (Fig. 2P), petals became green from the tips (Fig. 2Q), stamens occasionally had no pollen and also became green from the tops of the anthers (Fig. 2R), and pistils were replaced by leaf-like structures (Fig. 2S).

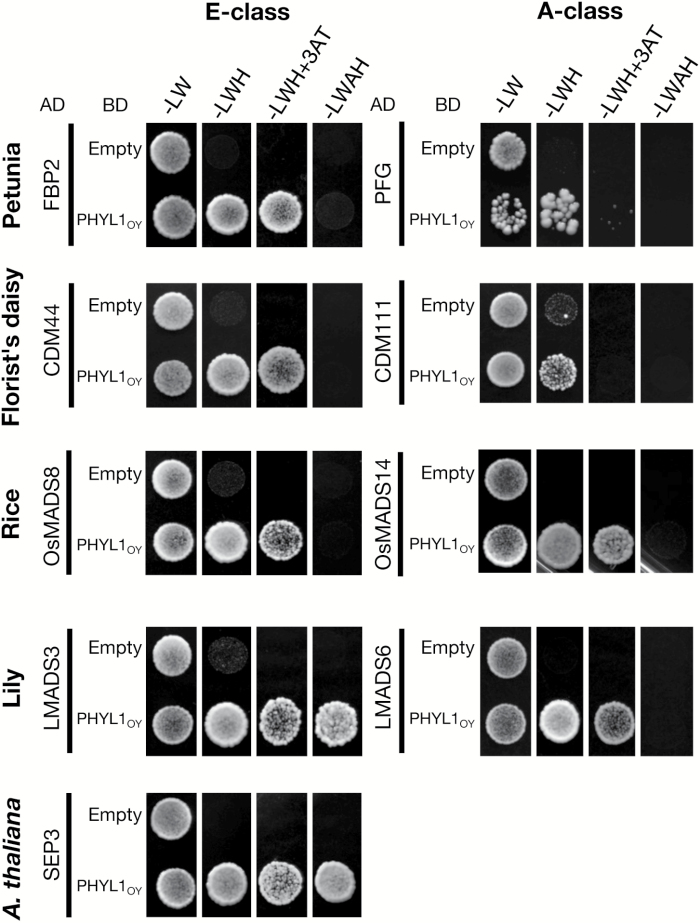

PHYL1OY targets A- and E-class MTFs of various plant species

To investigate whether PHYL1OY interacts with A- and E-class MTFs of diverse plant species and leads to their degradation, as in the case of A. thaliana, the activities of PHYL1OY against the MTFs from several angiosperms (Table 1) were examined. These MTFs were selected not only from the two eudicot species petunia (family Solanaceae) and florist’s daisy (Chrysanthemum morifolium, family Asteraceae), but also from the monocot species rice (Oryza sativa, family Poaceae) and lily (Lilium longiflorum, family Liliaceae). SEP3 of A. thaliana was used as a positive control. Yeast cells expressing BD-fused PHYL1OY (BD-PHYL1OY), and each of the AD-fused MTFs, grew on selective media, while no growth was observed in yeast expressing empty BD and the AD-fused MTFs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

PHYL1OY interacts with A- and E-class MADS domain transcription factors (MTFs) of angiosperms in yeast cells. The MTFs listed in Table 1 were fused to the GAL4 activation domain (AD). These AD-fused MTFs were expressed in the yeast strain AH109, with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD) or BD-fused PHYL1OY. The AD-fused SEP3 is a positive control, which interacts with PHYL1OY (Maejima et al., 2014a). Yeast cells harboring the appropriate AD and BD vectors were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.1. Aliquots (10 µl) of these cells were spotted on synthetically defined medium lacking leucine/tryptophan (–LW), lacking leucine/tryptophan/histidine (–LWH), lacking leucine/tryptophan/histidine and containing 5 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (–LWH+3AT), or lacking tryptophan/leucine/adenine/histidine (–LWAH). The plates were incubated for 4 d at 30 °C.

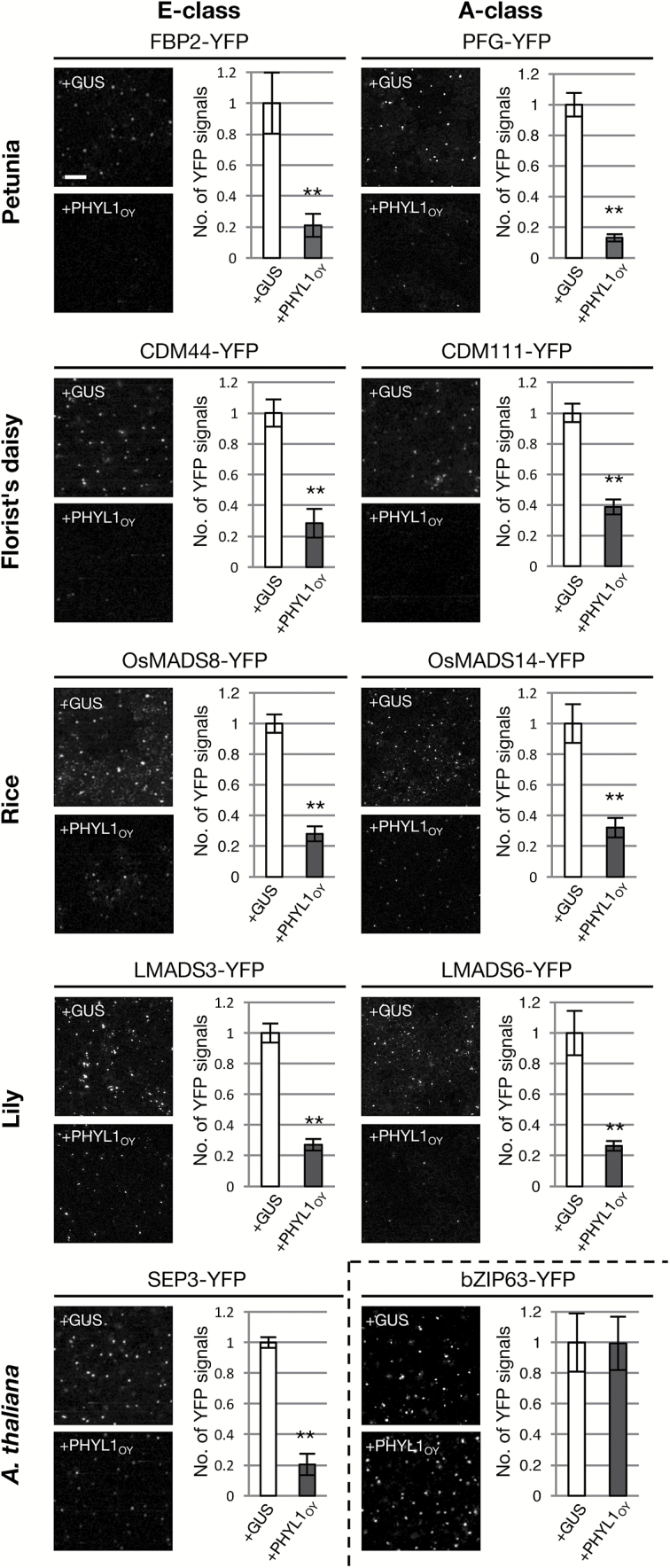

Next, to test whether the MTFs were degraded in the presence of PHYL1OYin planta, each of the YFP-fused MTFs was expressed transiently with PHYL1OY or GUS in N. benthamiana leaves by agro-infiltration. When GUS was co-expressed, YFP fluorescence signals were observed, mainly in the cell nuclei (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the YFP fluorescence signals were significantly reduced upon co-expression with PHYL1OY (Fig. 4), showing that PHYL1OY induced degradation of all of the MTFs used in this experiment. Co-expression of PHYL1OY did not affect the accumulation and subcellular localization of YFP-fused bZIP63, a nuclear-localized leucine zipper transcription factor (control).

Fig. 4.

PHYL1OY induces degradation of A- and E-class MADS domain transcription factors (MTFs) of angiosperms in Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells. Each of the MTFs was fused to the YFP protein and co-expressed with either GUS or PHYL1OY. We used bZIP63–YFP and SEP3–YFP as negative and positive controls, respectively. Agrobacterium cultures (OD600=1.0) carrying each of the YFP-fused proteins and those carrying either GUS or PHYL1OY were mixed at a ratio of 1:10, and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. YFP fluorescence was observed 36 h after infiltration. Graphs show the number of the YFP signals quantified in a relative manner. The average YFP signal of each MTF expressed with GUS was set as 1.0. Each bar represents the average of YFP signals observed in four leaf areas of 2.4 mm2. The bar indicates 100 µm. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with GUS (**P<0.01 by the one-tailed Student’s t-test). The experiment was performed independently three times. (This figure is available in colour at JXB online.)

PHYL1OY represses MTF gene expression in petunia

To investigate the indirect effects of phyllogen on the MTFs, the expression levels of ABCE-class genes and flowering time genes was examined in floral buds of petunia plants affected by PHYL1OY. The expression of MTF genes shown in Table 1 in ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected plants was analyzed by qRT-PCR and compared with that in ALSV-empty-infected plants (Fig. 5). The A-class genes (PFG, FBP29, and PhAP2A) were not affected by PHYL1OY. On the other hand, the B- (DEF and GLO1), C- (pMADS3 and FBP6), and E- (FBP2 and FBP5) class genes were down-regulated in ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected plants, although the differences were not statistically significant for pMADS3 (P=0.0573). The flowering time genes (UNS, FBP13, and FBP25) were not affected by PHYL1OY (Fig. 5). These results show that PHYL1OY affects the expression levels of the B-, C-, and E-class MTF genes in floral buds of petunia. Considering the induction of degradation of the A- and E-class MTF proteins (Fig. 4), PHYL1OY has negative effects on the expression of all of the ABCE-class MTFs in petunia at the mRNA or protein levels.

Fig. 5.

qRT-PCR analyses of MADS domain transcription factor (MTF) genes in floral buds of ALSV-empty- and ALSV-PHYL1OY-infected plants. Each bar represents the average of nine plants. The expression levels of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH) were used for normalization. The average expression levels in the control were set as 1.0. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the control (*P<0.05 by the two-tailed Student’s t-test).

PHYL1OY targets MTFs of gymnosperms and a fern

The interactions between PHYL1OY and the MTFs of two gymnosperms (CjMADS14 of Cryptomeria japonica and DAL1 of Picea abies; Supplementary Fig. S5) and the MTF of a fern (CRM6 of Ceratopteris pteridoides; Supplementary Fig. S5) were investigated by a Y2H assay. Yeast cells expressing BD-PHYL1OY and each of the AD-fused MTFs grew on selective media, while those expressing empty BD and the AD-fused MTFs did not (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, accumulation of each MTF in N. benthamiana leaves was evaluated using the YFP reporter assay, in combination with either the GUS protein or PHYL1OY. Because the subcellular localization of each of the YFP-fused MTFs was not limited to nuclei, the protein accumulation was confirmed by immunoblotting. Compared with GUS, co-expression with PHYL1OY decreased the amount of these MTFs significantly (Fig. 6B). These results showed that PHYL1OY interacted with, and induced degradation of these MTFs.

Fig. 6.

PHYL1OY targets the MTFs of gymnosperms and a fern. MADS domain transcription factors (MTFs) were chosen from two gymnosperms (CjMADS14 from Cryptomeria japonica and DAL1 from Picea abies) and a fern (CRM6 from Ceratopteris pteridoides). (A) A yeast two-hybrid assay showed interaction between PHYL1OY and the MTFs in yeast cells. Each of the AD-fused MTFs was expressed in the yeast strain AH109, with BD or BD-fused PHYL1OY. Experimental details are described in the legend to Fig. 3. (B) The YFP reporter assay showed PHYL1OY-dependent degradation of the MTFs in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Accumulation of each MTF was evaluated by immunoblotting using an anti-GFP antibody.

Discussion

The function and molecular mechanism of phyllogen as a phyllody-inducing factor has been elucidated only in A. thaliana, a well-studied and easily transformed model plant (MacLean et al., 2011; Maejima et al., 2014a; Yang et al., 2015). In this study, it was investigated whether phyllogen could induce phyllody phenotypes in various plants. Two phyllogens (PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB) were initially expressed in petunia, a model plant for genetic studies of floral organ development (Gerats and Vandenbussche, 2005; Rijpkema et al., 2006a). The results showed that PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB have phyllody-inducing activity in petunia (Fig. 1). They also induced phyllody and abnormal flower development in another solanaceous plant, N. benthamiana (Supplementary Fig. S3), indicating that PHYL1OY and PHYL1PnWB can induce phyllody in solanaceous plants. Moreover, PHYL1PnWB induced phyllody in sunflower (family Asteraceae; Fig. 2), China aster (family Asteraceae; Supplementary Fig. S4), and sesame (family Pedaliaceae; Fig. 2) when it was expressed using ALSV vector. Reports from previous studies on phyllogen-induced phyllody phenotypes in A. thaliana (MacLean et al., 2011; Maejima et al., 2014a; Yang et al., 2015) and the results from the current study indicate that phyllogen can induce phyllody phenotypes in eudicots, at least those belonging to the four families Brassicaceae, Solanaceae, Asteraceae, and Pedaliaceae. Furthermore, PHYL1OY recognized and induced degradation of the A- and E-class MTFs of two eudicots (petunia and the florist’s daisy), and also those of two monocots (rice and lily; Figs 3, 4), as in A. thaliana (Maejima et al., 2014a, 2015). This strongly suggests that PHYL1OY and other phyllogens can recognize A- and E-class MTFs in diverse angiosperms. In A. thaliana, phyllogen induces degradation of target MTFs via a proteasome-mediated pathway (MacLean et al., 2014; Maejima et al., 2014a). Considering that the ABCE-class MTF genes and the proteasome-mediated protein degradation pathway are conserved in plants (Ingvardsen and Veierskov, 2001; Zahn et al., 2005a; Kater et al., 2006), our results strongly suggest that phyllogen is a broad-spectrum virulence factor that can repress the functions of A- and E-class MTFs in a large range of angiosperm species.

It will be interesting to investigate whether phyllogen-mediated degradation of the MTFs (Figs 3, 4) affects the floral morphology of monocots. In rice, RNA silencing of two E-class genes (OsMADS7 and OsMADS8) causes severe morphological alterations of floral organs, including their conversion into leaf-like organs (Cui et al., 2010). In other monocot species, although information on loss-of-function mutants of A- and E-class genes is very limited, many reports suggest that A-class and E-class gene homologs are involved in floral organ development (Caporali et al., 2000; Yu and Goh, 2000; Adam et al., 2007; Acri-Nunes-Miranda and Mondragón-Palomino, 2014; Kubota and Kanno, 2015). Therefore, it is likely that phyllogen-mediated degradation of the A- and E-class MTFs induces phyllody or other flower malformations in monocots.

The phenotypes of PHYL1-affected petunia flowers were very similar to those of E-class knockdown or knockout petunia mutants, in terms of the development of size-reduced green corollas, transformation of stamens into green petaloid structures, and development of inflorescences in the axils of the carpels (Fig. 1; Angenent et al., 1994; Vandenbussche et al., 2003). In contrast, knockdown of A-class MTF genes in petunia does not produce leaf-like flower malformations (Immink et al., 1999). Moreover, in the petunia buds expressing PHYL1OY, the B- and C-class genes were down-regulated (Fig. 5), which was similar to the expression pattern in E-class knockdown in petunia (Angenent et al., 1994). These data suggest that downregulation of E-class MTFs, rather than A-class MTFs, contributes mainly to phyllogen-induced phyllody symptoms. This might be because E-class MTFs play an important role as mediators of every higher order complex formation in the floral quartet model (Smaczniak et al., 2012). Considering the previous findings that phyllogen also induces phyllody phenotypes and loss of floral meristem determinacy like E-class mutants (Pelaz et al., 2000; Ditta et al., 2004), and degrades all E-class MTFs of A. thaliana (Maejima et al., 2014a, 2015), it is reasonable to conclude that phyllody phenotypes induced by the expression of phyllogen are attributed largely to the degradation of E-class MTFs.

Gymnosperms and ferns have MTF genes phylogenetically related to MTFs of angiosperms (Theissen et al., 2000; Becker and Theissen, 2003; Gramzow et al., 2010; Gramzow et al., 2014). This work has shown that, in addition to recognizing MTFs from angiosperms, PHYL1OY recognized and induced degradation of MTFs from gymnosperms (CjMADS14 and DAL1; Fig. 6). CjMADS14 and DAL1 are assumed to belong to the AGL6-like protein family (Tandre et al., 1995; Futamura et al., 2008), being phylogenetically related to A- and E-class MTFs (Kim et al., 2013). AGL6, whose homologs exhibit E-class functions in some angiosperms (Rijpkema et al., 2009; Dreni and Zhang, 2016), has been shown to interact with a member of the phyllogen family, SAP54 (MacLean et al., 2014). Our data and the cited reports suggest that phyllogens generally recognize these closely related MTFs. Furthermore, PHYL1OY is shown to target CRM6, an MTF from a fern (Fig. 6). These data indicate that phyllogen may recognize a motif conserved in MTFs across the Plantae. MacLean et al. (2014) reported that SAP54 recognized the K-domains of MTFs of A. thaliana. Based on this report and the X-ray crystal structure of the K-domain of SEP3 (Puranik et al., 2014), Rümpler et al., (2015) suggested a hypothesized mode of interaction between SAP54 and MTFs. Our data will be useful to elucidate the conserved motif in the K-domain recognized by phyllogen, and to improve the hypothesis.

Broad-spectrum activity of phyllogen suggests that it can be used as a tool for engineering functions of MTFs. Because MTF repression could lead to unique and highly attractive flower malformations, MTFs are considered important targets for the genetic engineering of floral traits (Mol et al., 1995; Matsubara et al., 2008). RNA silencing is widely used to repress MTFs in many plant species (Angenent et al., 1994; Cui et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2015). Because RNA silencing is a sequence-specific repression method (Brodersen and Voinnet, 2006; Martínez de Alba et al., 2013), sequence information on target MTF genes is utilized for gene silencing in most studies (Aida et al., 2008; Galimba et al., 2012; Nakatsuka et al., 2015). However, the floral MTF sequences have not yet been elucidated for many horticultural plants. This study suggests that phyllogen induces phyllody and other flower malformations in a wide range of angiosperms, even if the plant species are not well studied genetically (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs S3, S4). Thus, phyllogen may be a useful alternative tool to engineer flower organs in a genetically dominant fashion. In addition, phyllogen is indicated to target MTFs of gymnosperms and ferns (Fig. 6). The functions of MTF genes in gymnosperms and ferns remain unclear, largely due to the lack of loss-of-function mutants. For example, ectopic expression analyses of CjMADS14 or DAL1 in A. thaliana suggest that these genes have been presumed to play a role during reproductive organ development (Carlsbecker et al., 2004; Katahata et al., 2014), but their actual functions in gymnosperms are not confirmed. This study suggests that phyllogen expression in gymnosperms and ferns would cause the inhibition of their MTF functions, which might be helpful to study their roles.

Considering that phytoplasmas infect hundreds of plant species, it appears that they have strategies to infect diverse host plants. Phytoplasmas are phloem-limited bacteria, and phyllody symptoms increase leaf-like organs where they can colonize (Arashida et al., 2008; Su et al., 2011). We found that phyllogen could induce phyllody in diverse plant species. This indicates that phyllogen creates favorable conditions for phytoplasma colonization in diverse angiosperms. Moreover, phytoplasmas can infect gymnosperms and cause symptoms such as stunting and needle malformations (Paltrinieri et al., 1998; Schneider et al., 2005; Davis et al., 2010; Kamińska and Berniak, 2011). It would be interesting to study whether phyllogen is involved in these symptoms through the degradation of the MTFs, although further studies are needed to understand the functions of phyllogen and MTFs in gymnosperms. Additionally, a recent report suggested that SAP54 was involved in insect attraction, independent of phyllody induction, in A. thaliana (Orlovskis and Hogenhout, 2016). Given the importance of insect transmission to phytoplasmas, it will be interesting to explore whether phyllogen also enhances insect preferences in other plant species.

It is common for functionally analyzed phytoplasma virulence factors to target diverse plant species. To date, three virulence factors have been identified in phytoplasmas: phyllogen, TENGU (Hoshi et al., 2009; Sugawara et al., 2013; Minato et al., 2014a), and SAP11 (Sugio et al., 2011, 2014; Tan et al., 2016; Janik et al., 2017). Functions of each protein were tested in several plant species belonging to different families. Functions of phyllogen were tested in A. thaliana, petunia, N. benthamiana, sunflower, China aster, and sesame; functions of TENGU were tested in A. thaliana and N. benthamiana; and functions of SAP11 were tested in A. thaliana and N. benthamiana. SAP11 was also suggested to function in apple (Tan et al., 2016). Virulence factors targeting diverse plants might be a common strategy for phytoplasmas to infect diverse plant species.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. The optimized nucleotide sequences of LMADS6 and PHYL1PnWB used in the present study.

Fig. S2. PHYL1PnWB interacts with SEP3 and induces its degradation.

Fig. S3. Characteristics of Nicotiana benthamiana flowers exhibiting phyllody.

Fig. S4. Characteristics of China aster flowers exhibiting phyllody.

Fig. S5. Unrooted phylogenetic tree of MTFs used in this study.

Table S1. Sequences of the primers used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (category ‘S’ of Scientific Research Grant 25221201) and Grants-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (Grant 15J11207) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

References

- Acri-Nunes-Miranda R, Mondragón-Palomino M. 2014. Expression of paralogous SEP-, FUL-, AG- and STK-like MADS-box genes in wild-type and peloric Phalaenopsis flowers. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam H, Jouannic S, Orieux Y, Morcillo F, Richaud F, Duval Y, Tregear JW. 2007. Functional characterization of MADS box genes involved in the determination of oil palm flower structure. Journal of Experimental Botany 58, 1245–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida R, Komano M, Saito M, Nakase K, Murai K. 2008. Chrysanthemum flower shape modification by suppression of chrysanthemum-AGAMOUS gene. Plant Biotechnology 25, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar KP, Sarwar G, Dickinson M, Ahmad M, Haq MA, Hameed S, Iqbal MJ. 2009. Sesame phyllody disease: its symptomatology, etiology, and transmission in Pakistan. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 33, 477–486. [Google Scholar]

- Angenent GC, Franken J, Busscher M, Weiss D, Tunen AJ. 1994. Co-suppression of the petunia homeotic gene fbp2 affects the identity of the generative meristem. The Plant Journal 5, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arashida R, Kakizawa S, Ishii Y, Hoshi A, Jung HY, Kagiwada S, Yamaji Y, Oshima K, Namba S. 2008. Cloning and characterization of the antigenic membrane protein (Amp) gene and in situ detection of Amp from malformed flowers infected with Japanese hydrangea phyllody phytoplasma. Phytopathology 98, 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker A, Theissen G. 2003. The major clades of MADS-box genes and their role in the development and evolution of flowering plants. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 29, 464–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Carpenter R, Sommer H, Hartley N, Coen E. 1993. Complementary floral homeotic phenotypes result from opposite orientations of a transposon at the plena locus of Antirrhinum. Cell 72, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Voinnet O. 2006. The diversity of RNA silencing pathways in plants. Trends in Genetics 22, 268–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporali E, Spada A, Losa A, Marziani G. 2000. The MADS box gene AOM1 is expressed in reproductive meristems and flowers of the dioecious species Asparagus officinalis. Sexual Plant Reproduction 13, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Carlsbecker A, Tandre K, Johanson U, Englund M, Engström P. 2004. The MADS-box gene DAL1 is a potential mediator of the juvenile-to-adult transition in Norway spruce (Picea abies). The Plant Journal 40, 546–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S, Puryear J, Cairney J. 1993. A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 11, 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi Y, Rao GP, Tiwari AK, Duduk B, Bertaccini A. 2010. Phytoplasma on ornamentals: detection, diversity and management. Acta Phytopathologica et Entomologica Hungarica 45, 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- Chen MK, Lin IC, Yang CH. 2008. Functional analysis of three lily (Lilium longiflorum) APETALA1-like MADS box genes in regulating floral transition and formation. Plant and Cell Physiology 49, 704–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WC, Chen LL, Lo WS, Lin CP, Kuo CH. 2013. Comparative analysis of the peanut witches’-broom phytoplasma genome reveals horizontal transfer of potential mobile units and effectors. PLoS One 8, e62770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui R, Han J, Zhao S, Su K, Wu F, Du X, Xu Q, Chong K, Theissen G, Meng Z. 2010. Functional conservation and diversification of class E floral homeotic genes in rice (Oryza sativa). The Plant Journal 61, 767–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RE, Dally EL, Zhao Y, Lee I-M, Jomantiene R, Detweiler AJ, Putnam ML. 2010. First report of a new subgroup 16SrIX-E (‘Candidatus Phytoplasma phoenicium’-related) phytoplasma associated with juniper witches’ broom disease in Oregon, USA. Plant Pathology 59, 1161. [Google Scholar]

- Ditta G, Pinyopich A, Robles P, Pelaz S, Yanofsky MF. 2004. The SEP4 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana functions in floral organ and meristem identity. Current Biology 14, 1935–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreni L, Kater MM. 2014. MADS reloaded: evolution of the AGAMOUS subfamily genes. New Phytologist 201, 717–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreni L, Zhang D. 2016. Flower development: the evolutionary history and functions of the AGL6 subfamily MADS-box genes. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 1625–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS. 2006. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. The Plant Journal 45, 616–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi MM, Taghavi SM, Salehi M, Sadeghi MS, Samavi S, Siampour M. 2014. Characterisation of a phytoplasma associated with Petunia witches’ broom disease in Iran. New Disease Reports 30, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario S, Busscher J, Franken J, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M, Angenent GC, Immink RG. 2004. Ectopic expression of the petunia MADS box gene UNSHAVEN accelerates flowering and confers leaf-like characteristics to floral organs in a dominant-negative manner. The Plant Cell 16, 1490–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrario S, Immink RG, Shchennikova A, Busscher-Lange J, Angenent GC. 2003. The MADS box gene FBP2 is required for SEPALLATA function in petunia. The Plant Cell 15, 914–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futamura N, Totoki Y, Toyoda A, et al. 2008. Characterization of expressed sequence tags from a full-length enriched cDNA library of Cryptomeria japonica male strobili. BMC Genomics 9, 383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galimba KD, Tolkin TR, Sullivan AM, Melzer R, Theißen G, di Stilio VS. 2012. Loss of deeply conserved C-class floral homeotic gene function and C- and E-class protein interaction in a double-flowered ranunculid mutant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, E2267–E2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. 2005. A model system for comparative research: Petunia. Trends in Plant Science 10, 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L, Ritz MS, Theißen G. 2010. On the origin of MADS-domain transcription factors. Trends in Genetics 26, 149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramzow L, Weilandt L, Theißen G. 2014. MADS goes genomic in conifers: towards determining the ancestral set of MADS-box genes in seed plants. Annals of Botany 114, 1407–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán F, Giolitti F, Fernández F, Nome C, Lenardon S, Conci L. 2014. Identification and molecular characterization of a phytoplasma associated with sunflower in Argentina. European Journal of Plant Pathology 138, 679–683. [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans K, Ament K, Rijpkema AS, Zethof J, Wolters-Arts M, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. 2012a Redefining C and D in the petunia ABC. The Plant Cell 24, 2305–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans K, Morel P, Vandenbussche M. 2012b MADS-box genes and floral development: the dark side. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 5397–5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himeno M, Maejima K, Komatsu K, Ozeki J, Hashimoto M, Kagiwada S, Yamaji Y, Namba S. 2010. Significantly low level of small RNA accumulation derived from an encapsidated mycovirus with dsRNA genome. Virology 396, 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himeno M, Neriya Y, Minato N, et al. 2011. Unique morphological changes in plant pathogenic phytoplasma-infected petunia flowers are related to transcriptional regulation of floral homeotic genes in an organ-specific manner. The Plant Journal 67, 971–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honma T, Goto K. 2001. Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 409, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi A, Oshima K, Kakizawa S, et al. 2009. A unique virulence factor for proliferation and dwarfism in plants identified from a phytopathogenic bacterium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 6416–6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immink RG, Ferrario S, Busscher-Lange J, Kooiker M, Busscher M, Angenent GC. 2003. Analysis of the petunia MADS-box transcription factor family. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 268, 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immink RGH, Gadella TWJ, Ferrario S, Busscher M, Angenent GC. 2002. Analysis of MADS box protein–protein interactions in living plant cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 99, 2416–2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immink RGH, Hannapel DJ, Ferrario S, Busscher M, Franken J, Campagne ML, Angenent GC. 1999. A petunia MADS box gene involved in the transition from vegetative to reproductive development. Development 126, 5117–5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvardsen C, Veierskov B. 2001. Ubiquitin- and proteasome-dependent proteolysis in plants. Physiologia Plantarum 112, 451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janik K, Mithöfer A, Raffeiner M, Stellmach H, Hause B, Schlink K. 2017. An effector of apple proliferation phytoplasma targets TCP transcription factors—a generalized virulence strategy of phytoplasma?Molecular Plant Pathology 18, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JS, Lee S, Jung KH, Yang WS, Yi GH, Oh BG, An G. 2000. Production of transgenic rice plants showing reduced heading date and plant height by ectopic expression of rice MADS-box genes. Molecular Breeding 6, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiñska M, Berniak H. 2011. Detection and identification of three ‘Candidatus phytoplasma’ species in Picea spp. trees in Poland. Journal of Phytopathology 159, 796–798. [Google Scholar]

- Kanno A. 2016. Molecular mechanism regulating floral architecture in monocotyledonous ornamental plants. Horticulture Journal 85, 8–22. [Google Scholar]

- Katahata SI, Futamura N, Igasaki T, Shinohara K. 2014. Functional analysis of SOC1-like and AGL6-like MADS-box genes of the gymnosperm Cryptomeria japonica. Tree Genetics and Genomes 10, 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kater MM, Colombo L, Franken J, Busscher M, Masiero S, Campagne MML, Angenent GC. 1998. Multiple AGAMOUS homologs from cucumber and petunia differ in their ability to induce reproductive organ fate. The Plant Cell 10, 171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater MM, Dreni L, Colombo L. 2006. Functional conservation of MADS-box factors controlling floral organ identity in rice and Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 3433–3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. 2013. AGL6-like MADS-box genes are sister to AGL2-like MADS-box genes. Journal of Plant Biology 56, 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Krizek BA, Fletcher JC. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of flower development: an armchair guide. Nature Reviews Genetics 6, 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota S, Kanno A. 2015. Analysis of the floral MADS-box genes from monocotyledonous Trilliaceae species indicates the involvement of SEPALLATA3-like genes in sepal–petal differentiation. Plant Science 241, 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IM, Davis RE, Gundersen-Rindal DE. 2000. Phytoplasma: phytopathogenic mollicutes. Annual Review of Microbiology 54, 221–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Sasaki N, Isogai M, Yoshikawa N. 2004. Stable expression of foreign proteins in herbaceous and apple plants using Apple latent spherical virus RNA2 vectors. Archives of Virology 149, 1541–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean AM, Orlovskis Z, Kowitwanich K, Zdziarska AM, Angenent GC, Immink RG, Hogenhout SA. 2014. Phytoplasma effector SAP54 hijacks plant reproduction by degrading MADS-box proteins and promotes insect colonization in a RAD23-dependent manner. PLoS Biology 12, e1001835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean AM, Sugio A, Makarova OV, Findlay KC, Grieve VM, Tóth R, Nicolaisen M, Hogenhout SA. 2011. Phytoplasma effector SAP54 induces indeterminate leaf-like flower development in Arabidopsis plants. Plant Physiology 157, 831–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima K, Iwai R, Himeno M, et al. 2014a Recognition of floral homeotic MADS domain transcription factors by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen, induces phyllody. The Plant Journal 78, 541–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima K, Kitazawa Y, Tomomitsu T, Yusa A, Neriya Y, Himeno M, Yamaji Y, Oshima K, Namba S. 2015. Degradation of class E MADS-domain transcription factors in Arabidopsis by a phytoplasmal effector, phyllogen. Plant Signaling and Behavior 10, e1042635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maejima K, Oshima K, Namba S. 2014b Exploring the phytoplasmas, plant pathogenic bacteria. Journal of General Plant Pathology 80, 210–221. [Google Scholar]

- Maes T, Van de Steene N, Zethof J, Karimi M, D’Hauw M, Mares G, Van Montagu M, Gerats T. 2001. Petunia Ap2-like genes and their role in flower and seed development. The Plant Cell 13, 229–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de Alba AE, Elvira-Matelot E, Vaucheret H. 2013. Gene silencing in plants: a diversity of pathways. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1829, 1300–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Shimamura K, Kodama H, Kokubun H, Watanabe H, Basualdo IL, Ando T. 2008. Green corolla segments in a wild Petunia species caused by a mutation in FBP2, a SEPALLATA-like MADS box gene. Planta 228, 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer VG. 1966. Flower abnormalities. Botanical Review 32, 165–218. [Google Scholar]

- Meyerowitz EM, Smyth DR, Bowman JL. 1989. Abnormal flowers and pattern formation in floral development. Development 106, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Minato N, Himeno M, Hoshi A, et al. 2014a The phytoplasmal virulence factor TENGU causes plant sterility by downregulating of the jasmonic acid and auxin pathways. Scientific Reports 4, 7399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minato N, Komatsu K, Okano Y, Maejima K, Ozeki J, Senshu H, Takahashi S, Yamaji Y, Namba S. 2014b Efficient foreign gene expression in planta using a Plantago asiatica mosaic virus-based vector achieved by the strong RNA-silencing suppressor activity of TGBp1. Archives of Virology 159, 885–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol JNM, Holton TA, Koes RE. 1995. Floriculture: genetic engineering of commercial traits. Trends in Biotechnology 13, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Münster T, Pahnke J, Di Rosa A, Kim JT, Martin W, Saedler H, Theissen G. 1997. Floral homeotic genes were recruited from homologous MADS-box genes preexisting in the common ancestor of ferns and seed plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 94, 2415–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka T, Saito M, Yamada E, Fujita K, Yamagishi N, Yoshikawa N, Nishihara M. 2015. Isolation and characterization of the C-class MADS-box gene involved in the formation of double flowers in Japanese gentian. BMC Plant Biology 15, 182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlovskis Z, Hogenhout SA. 2016. A bacterial parasite effector mediates insect vector attraction in host plants independently of developmental changes. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltrinieri S, Martini M, Pondrelli M, Bertaccini A. 1998. X-disease related phytoplasmas in ornamental trees and shrubs with witches’ broom and malformation symptoms. Journal of Plant Pathology 80, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz S, Ditta GS, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF. 2000. B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405, 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puranik S, Acajjaoui S, Conn S, et al. 2014. Structural basis for the oligomerization of the MADS domain transcription factor SEPALLATA3 in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 26, 3603–3615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema A, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. 2006a Genetics of floral development in Petunia. Advances in Botanical Research 44, 237–278. [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema AS, Royaert S, Zethof J, van der Weerden G, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. 2006b Analysis of the Petunia TM6 MADS box gene reveals functional divergence within the DEF/AP3 lineage. The Plant Cell 18, 1819–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema AS, Vandenbussche M, Koes R, Heijmans K, Gerats T. 2010. Variations on a theme: changes in the floral ABCs in angiosperms. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 21, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijpkema AS, Zethof J, Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. 2009. The petunia AGL6 gene has a SEPALLATA-like function in floral patterning. The Plant Journal 60, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rümpler F, Gramzow L, Theißen G, Melzer R. 2015. Did convergent protein evolution enable phytoplasmas to generate ‘zombie plants’?Trends in Plant Science 20, 798–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Torres E, Martín MP, Schröder M, Behnke HD, Seemüller E. 2005. ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma pini’, a novel taxon from Pinus silvestris and Pinus halepensis. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 55, 303–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senshu H, Ozeki J, Komatsu K, Hashimoto M, Hatada K, Aoyama M, Kagiwada S, Yamaji Y, Namba S. 2009. Variability in the level of RNA silencing suppression caused by triple gene block protein 1 (TGBp1) from various potexviruses during infection. Journal of General Virology 90, 1014–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan H, Zhang N, Liu C, Xu G, Zhang J, Chen Z, Kong H. 2007. Patterns of gene duplication and functional diversification during the evolution of the AP1/SQUA subfamily of plant MADS-box genes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44, 26–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchennikova AV, Shulga OA, Immink R, Skryabin KG, Angenent GC. 2004. Identification and characterization of four chrysanthemum MADS-box genes, belonging to the APETALA1/FRUITFULL and SEPALLATA3 subfamilies. Plant Physiology 134, 1632–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada TL, Shimada T, Hara-Nishimura I. 2010. A rapid and non-destructive screenable marker, FAST, for identifying transformed seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 61, 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha RC, Paliwal YC. 1969. Association, development, and growth cycle of mycoplasma-like organisms in plants affected with clover phyllody. Virology 39, 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaczniak C, Immink RGH, Angenent GC, Kaufmann K. 2012. Developmental and evolutionary diversity of plant MADS-domain factors: insights from recent studies. Development 139, 3081–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Chanderbali AS, Kim S, Buzgo M, Soltis PS. 2007. The ABC model and its applicability to basal angiosperms. Annals of Botany 100, 155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E. 2009. Phytoplasma research begins to bloom. Science 325, 388–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su YT, Chen JC, Lin CP. 2011. Phytoplasma-induced floral abnormalities in Catharanthus roseus are associated with phytoplasma accumulation and transcript repression of floral organ identity genes. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 24, 1502–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara K, Honma Y, Komatsu K, Himeno M, Oshima K, Namba S. 2013. The alteration of plant morphology by small peptides released from the proteolytic processing of the bacterial peptide TENGU. Plant Physiology 162, 2005–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio A, MacLean AM, Grieve VM, Hogenhout SA. 2011. Phytoplasma protein effector SAP11 enhances insect vector reproduction by manipulating plant development and defense hormone biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, E1254–E1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio A, MacLean AM, Hogenhout SA. 2014. The small phytoplasma virulence effector SAP11 contains distinct domains required for nuclear targeting and CIN–TCP binding and destabilization. New Phytologist 202, 838–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Fan Z, Li X, Liu Z, Li J, Yin H. 2014. Distinct double flower varieties in Camellia japonica exhibit both expansion and contraction of C-class gene expression. BMC Plant Biology 14, 288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan CM, Li CH, Tsao NW, et al. 2016. Phytoplasma SAP11 alters 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine biosynthesis in Nicotiana benthamiana by suppressing NbOMT1. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 4415–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandre K, Albert VA, Sundås A, Engström P. 1995. Conifer homologues to genes that control floral development in angiosperms. Plant Molecular Biology 27, 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira da Silva JA, Aceto S, Liu W, Yu H, Kanno A. 2014. Genetic control of flower development, color and senescence of Dendrobium orchids. Scientia Horticulturae 175, 74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Theissen G, Becker A, Di Rosa A, Kanno A, Kim JT, Münster T, Winter KU, Saedler H. 2000. A short history of MADS-box genes in plants. Plant Molecular Biology 42, 115–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theißen G, Melzer R, Rümpler F. 2016. MADS-domain transcription factors and the floral quartet model of flower development: linking plant development and evolution. Development 143, 3259–3271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchimoto S, van der Krol AR, Chua NH. 1993. Ectopic expression of pMADS3 in transgenic petunia phenocopies the petunia blind mutant. The Plant Cell 5, 843–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng TY, Hsiao CC, Chi PJ, Yang CH. 2003. Two lily SEPALLATA-like genes cause different effects on floral formation and floral transition in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 133, 1091–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbussche M, Zethof J, Royaert S, Weterings K, Gerats T. 2004. The duplicated B-class heterodimer model: whorl-specific effects and complex genetic interactions in Petunia hybrida flower development. The Plant Cell 16, 741–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbussche M, Zethof J, Souer E, Koes R, Tornielli GB, Pezzotti M, Ferrario S, Angenent GC, Gerats T. 2003. Toward the analysis of the Petunia MADS box gene family by reverse and forward transposon insertion mutagenesis approaches: B, C, and D floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA-like MADS box genes in petunia. The Plant Cell 15, 2680–2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Krol AR, Brunelle A, Tsuchimoto S, Chua NH. 1993. Functional analysis of petunia floral homeotic MADS box gene pMADS1. Genes and Development 7, 1214–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MQ, Maramorosch K. 1988. Earliest historical record of a tree mycoplasma disease: beneficial effect of mycoplasma-like organisms on peonies. In: Maramorosch K, Raychaudhuri SP, eds. Mycoplasma diseases of crops. Heidelberg: Springer, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Liao H, Zhang W, Yu X, Zhang R, Shan H, Duan X, Yao X, Kong H. 2015. Flexibility in the structure of spiral flowers and its underlying mechanisms. Nature Plants 2, 15188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmer F, Graciet E, Riechmann JL. 2014. Specification of floral organs in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagishi N, Sasaki S, Yamagata K, Komori S, Nagase M, Wada M, Yamamoto T, Yoshikawa N. 2011. Promotion of flowering and reduction of a generation time in apple seedlings by ectopical expression of the Arabidopsis thaliana FT gene using the Apple latent spherical virus vector. Plant Molecular Biology 75, 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaji Y, Kobayashi T, Hamada K, Sakurai K, Yoshii A, Suzuki M, Namba S, Hibi T. 2006. In vivo interaction between Tobacco mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase and host translation elongation factor 1A. Virology 347, 100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Zhang H, Wang Q, et al. 2016. The Rosa chinensis cv. Viridiflora phyllody phenotype is associated with misexpression of flower organ identity genes. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CY, Huang YH, Lin CP, Lin YY, Hsu HC, Wang CN, Liu LY, Shen BN, Lin SS. 2015. MicroRNA396-targeted SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE is required to repress flowering and is related to the development of abnormal flower symptoms by the phyllody symptoms1 effector. Plant Physiology 168, 1702–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanofsky MF, Ma H, Bowman JL, Drews GN, Feldmann KA, Meyerowitz EM. 1990. The protein encoded by the Arabidopsis homeotic gene agamous resembles transcription factors. Nature 346, 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Nagato Y. 2011. Flower development in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 4719–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Goh CJ. 2000. Identification and characterization of three orchid MADS-box genes of the AP1/AGL9 subfamily during floral transition. Plant Physiology 123, 1325–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn LM, Kong H, Leebens-Mack JH, Kim S, Soltis PS, Landherr LL, Soltis DE, dePamphilis CW, Ma H. 2005a The evolution of the SEPALLATA subfamily of MADS-box genes. Genetics 169, 2209–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn LM, Leebens-Mack J, DePamphilis CW, Ma H, Theissen G. 2005b To B or not to B a flower: the role of DEFICIENS and GLOBOSA orthologs in the evolution of the angiosperms. Journal of Heredity 96, 225–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.