Summary

Among 26 asymptomatic men enrolled in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, valganciclovir, 900 mg daily, substantially reduced both the proportion of days on which Epstein-Barr virus was detected on oropharyngeal swabs and the quantity of virus present.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, valganciclovir, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder, infectious mononucleosis, viral shedding

Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) causes infectious mononucleosis and can lead to lymphoproliferative diseases. We evaluated the effects of valganciclovir on oral EBV shedding in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Twenty-six men received oral valganciclovir or daily placebo for 8 weeks, followed by a 2-week “washout period” and then 8 weeks of the alternative treatment. Valganciclovir reduced the proportion of days with EBV detected from 61.3% to 17.8% (relative risk, 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], .21–.41; P < .001), and quantity of virus detected by 0.77 logs (95% CI, .62–.91 logs; P < .001). Further investigations into the impact of valganciclovir on EBV-associated diseases are needed.

Primary infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is usually subclinical; however, EBV is the main cause of infectious mononucleosis. Following acute infection, the virus persists in host B and T lymphocytes, monocytes, and epithelial cells; asymptomatic salivary viral shedding leads to onward transmission [1]. Unlike other herpesviruses, EBV can cause B-cell transformation and is associated with malignancies including Hodgkin, non-Hodgkin, Burkitt, and primary central nervous system lymphomas, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD), nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and gastric cancer [2].

The role of antiviral therapies in the treatment of acute and chronic EBV-associated disease is unclear. Acyclovir reduces EBV replication by inhibiting viral DNA polymerase, and studies have found that both acyclovir and the prodrug valacyclovir reduce oral shedding of EBV in patients with infectious mononucleosis. However, only 1 study suggested that valacyclovir (1 g every 8 hours for 14 days) expedited the resolution of clinical symptoms associated with infectious mononucleosis [3]. Furthermore, case reports and small studies have suggested a possible role for antiviral treatment of PTLD and EBV-associated hemophagocytic syndrome [4], although definitive data have remained elusive.

Valganciclovir, an oral valine ester prodrug of the antiviral ganciclovir, is indicated for treatment of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Few data exist examining the impact of valganciclovir on EBV replication in vivo, though a recent study of valganciclovir on T-cell activation in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–infected participants found a significant decline in levels of salivary EBV among those on valganciclovir [5]. Additionally, observational data support the role of valganciclovir in suppressing replication and reducing clinical disease associated with EBV [6]. Our group previously conducted a randomized controlled trial to determine the impact of valganciclovir on oral shedding rates of human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and CMV, and found the drug reduced shedding of both viruses significantly [7]. Using oral swabs collected from this study, we sought to determine the impact of valganciclovir on in vivo replication of EBV.

METHODS

Study Participants, Setting, and Design

Men with oropharyngeal HHV-8 detected on ≥40% of days in prior studies were recruited for enrollment [7]. We excluded potential participants if they were taking medications with known activity against human herpesviruses, had known bone marrow suppression, hypersensitivity to ganciclovir, renal or hepatic dysfunction, or a history of CMV disease. Persons with HIV on antiretroviral therapy (ART) were required to remain on a stable regimen throughout the study period. The study was conducted at the University of Washington Virology Research Clinic in Seattle, Washington, between February 2003 and February 2005. The study protocol was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Review Board and all participants signed a consent form.

The study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Randomization was completed through a computer-generated random number assignment and stratified by HIV status. Study participants were randomly assigned to receive either oral valganciclovir 900 mg daily or matching placebo, once daily for 8 weeks. Following the initial 8-week administration of either valganciclovir or placebo, participants received no study drug for a 2-week washout period. Subsequently, participants received the alternative treatment (valganciclovir or placebo) for a second 8-week period. All participants collected daily oropharyngeal swabs and maintained a diary of symptoms, missed school or work days, and visits to a healthcare provider.

Laboratory Analysis

Serum samples were tested for HIV and CMV antibodies using commercial enzyme immunoassays. DNA was extracted from oropharyngeal swabs for real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of EBV using primers to amplify the BALF5 gene. Swabs were considered positive for oral EBV shedding if PCR analysis detected ≥150 copies of EBV DNA per milliliter.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoint for this analysis was the reduction in frequency of oral EBV shedding, defined as the ratio of days on which EBV was detected of all days on which oral samples were obtained, during valganciclovir administration compared with placebo. Additionally, the reduction in the quantity of EBV shed was determined on the days with EBV detection. The crossover study design allowed each individual to serve as his own control.

To evaluate the efficacy of valganciclovir in reducing EBV shedding frequency, we created generalized linear mixed models using the Poisson distribution and log link. To evaluate the efficacy of valganciclovir in reducing the quantity of EBV, we used linear mixed-effects models. The mean log10 copies per milliliter of EBV detected was calculated using all days on which EBV was detected. We tested the period and sequence effect by creating covariates for time period and for the interaction between time period and treatment.

RESULTS

Twenty-six men were enrolled, with a median age of 42 years (range, 24–66 years). Most participants (65%) reported their race as white. All participants self-identified as men who have sex with men (MSM), and 16 participants (62%) were HIV-1 infected. Among HIV-1–infected men, the median HIV-1 RNA plasma level was log10 3.7 copies per mL (range, 1.2–5.3 copies/mL), and median CD4 T-cell count was 434 cells/μL (range, 49–936 cells/mL). Eight of 16 HIV-1–infected individuals were receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) with at least 3 medications [7].

Because swabs were collected daily for 8 weeks during both the placebo and drug arms, each participant was expected to submit 56 swabs per study arm, and an additional 14 swabs during the washout period. Participants collected a mean of 49 swabs (range, 29–62 swabs) on the valganciclovir arm and a mean of 50 swabs (range, 3–61 swabs) on the placebo arm. Of 3276 anticipated swabs, 2931 (89.5%) were submitted by participants for analysis.

Of 5560 pills dispensed, 286 (5.1%) were returned, resulting in an estimated median adherence rate of 97.1% (range, 73%–100%). Adherence rates were similar in the placebo and valganciclovir study arms (P = .68) [7]. Medication was well tolerated; no serious adverse events occurred throughout the study. No participant experienced renal insufficiency, anemia, or thrombocytopenia on either placebo or valganciclovir [7].

Impact of Valganciclovir on Oropharyngeal Shedding of EBV

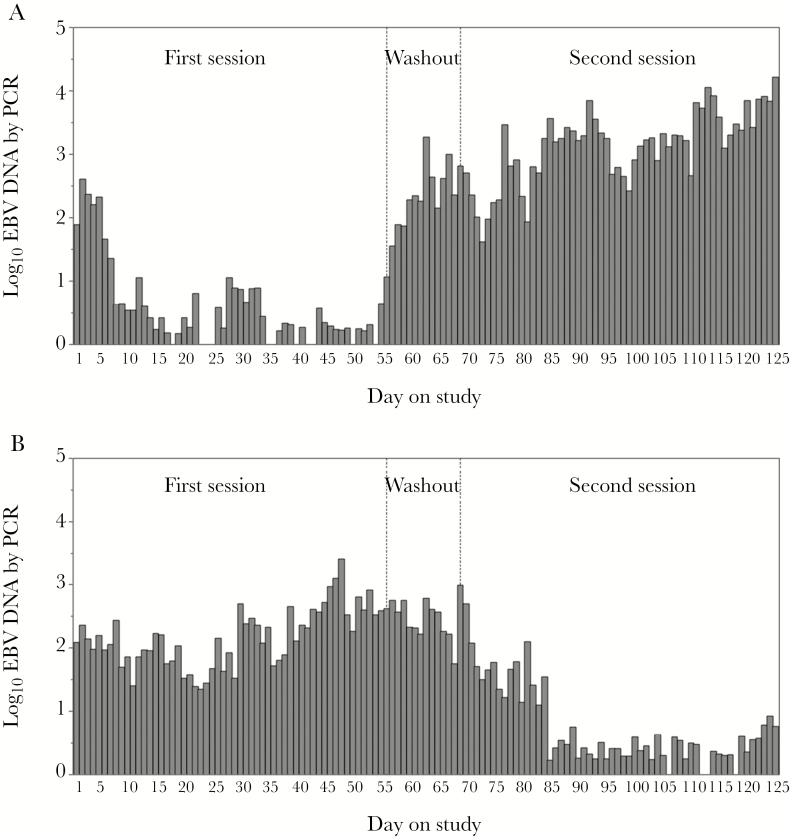

EBV was detected at least once in 25 of 26 participants. During valganciclovir administration, EBV was detected in oropharyngeal secretions on 229 of 1286 days (17.8%), compared with 803 of 1309 days (61.3%) on placebo, yielding a 72% reduction in the frequency of EBV shedding on valganciclovir compared with placebo (relative risk [RR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], .21–.41; P < .001). The quantity of EBV shed in the oropharynx on days with virus detected was also reduced from a mean of 4.3 log10 copies/mL (standard deviation [SD], 1.2 log10 copies/mL) of EBV during placebo administration compared with a mean of 3.6 (SD, 1.2 log10 copies/mL) of EBV during valganciclovir administration (Figure 1). Valganciclovir therefore reduced the quantity of EBV by 0.77 logs (95% CI, .62–.91 logs; P < .001) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Quantity of Epstein-Barr virus shed by study arm: valganciclovir administered first (A); valganciclovir administered second (B). Abbreviations: EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Table 1.

Rate and Quantity of Viral Shedding Among Study Participants by Human Immunodeficiency Virus Status, Antiretroviral Medication Use, and Study Arm

| Rate/Quantity | Valganciclovir | Placebo | Measure of Effect (95% CI)a |

P Valuea | ||||||

| HIV Infected (n = 16) |

HIV Uninfected (n = 10) | Total (N = 26) |

HIV Infected (n = 16) |

HIV Uninfected (n = 10) |

Total (N = 26) |

|||||

| HAART (n = 8) |

No HAART (n = 8) |

HAART (n = 8) |

No HAART (n = 8) |

|||||||

| EBV shedding rateb | 26.6 (110/414) | 20.5 (84/409) | 7.6 (35/463) | 17.8 (229/1286) | 81.1 (304/375) | 84.3 (359/426) | 27.6 (140/508) | 61.3 (803/1309) | RR, 0.28 (.21–.41) | <.001 |

| Mean quantity EBV detectedc,d | 3.9 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.2) | 4.2 (1.2) | 4.7 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.1) | 4.3 (1.2) | Coefficient –0.77 (.62–.91) |

<.001 |

| CMV shedding rateb | 4.6 (19/414) | 0.5 (2/407) | 2.0 (8/394) | 2.4 (29/1215) | 12.9 (48/373) | 12.2 (52/425) | 11.8 (54/457) | 12.3 (154/1255) | RR, 0.18 (.07–.47) | .001 |

| Mean quantity CMV detectedc,d | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 2.8 (0.4) | 4.5 (1.0) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.5 (1.0) | Coefficient –0.54 (.22–.87) |

<.001 |

| HHV-8 shedding rateb | 18.1 (78/430) | 40.6 (172/424) | 14.4 (73/506) | 23.8 (323/1360) | 45.2 (180/398) | 65.9 (280/425) | 28.6 (146/511) | 45.4 (606/1334) | RR, 0.54 (.33–.89) | .019 |

| Mean quantity HHV-8 detectedc,d | 4.0 (0.9) | 4.7 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.2) | 4.6 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.0) | 4.9 (1.1) | Coefficient –0.46 (.34–.58) |

<.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; HHV-8, human herpesvirus type 8; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; RR, relative risk.

aMeasure of effect and P value for comparison of valganciclovir to placebo.

bPercentage (positive swabs / total swabs collected).

cLog10 copies/mL.

dMean (standard deviation).

While on placebo, HIV-1–uninfected participants had EBV detected on 27.6% of days evaluated, compared with 81.1% for HIV-1–infected individuals receiving cART and 84.4% for HIV-infected individuals not receiving cART. While on valganciclovir, HIV-1–uninfected participants had EBV detected on 7.6% of days evaluated, compared with 26.6% for HIV-1–infected individuals receiving cART and 20.5% for HIV-1–infected individuals not receiving cART (Table 1). However, the effect of valganciclovir was similar regardless of HIV-1 status, with a 72.4% reduction in EBV shedding frequency among HIV-1–uninfected participants and a 71.5% reduction among HIV-1–infected participants.

When we adjusted for HIV status and cART use, the impact of valganciclovir on EBV shedding frequency and quantity remained unchanged. When we included the interactions of both HIV status and cART receipt on valganciclovir use in the model, we did not find a significant difference in the impact of valganciclovir use based on HIV status (P = .99). The model did not change when covariates accounting for either time period or interactions between time period and valganciclovir use were included, indicating that there was no sequence effect and that the 14-day washout period was sufficient.

Discussion

Our results indicate that oral valganciclovir administered once daily substantially reduced both the rate of oral EBV shedding and the quantity of virus shed. The effect was equally pronounced among HIV-infected and -uninfected men.

Prior studies have reported a similar impact of other antiviral therapies during acute EBV infection [3]. However, reduced viral shedding was not associated with significant changes in the duration of clinical symptoms or in overall clinical outcomes [8].

Recipients both of solid organ transplant (SOT) and of hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) are at risk for PTLD. Though the widespread use of rituximab therapy has dramatically improved PTLD survival rates, mortality following PTLD diagnosis remains approximately 27%–30% [9]. The effect of antiviral prophylaxis on the risk of PTLD varies between studies, with some showing no effect. However, one study reported a reduction in PTLD incidence from 3.9% to 0.5% of SOT recipients who received either acyclovir (administered orally 4 times daily) or ganciclovir (administered intravenously) during highly immunosuppressive antilymphocyte antibody therapy [10]. A subsequent multicenter case-control study evaluating renal-only transplants found up to an 83% reduction in the risk of PTLD, with variation between antiviral agents. Notably, ganciclovir was associated with a 38% risk reduction of early PTLD for each 30-day period during an individual’s first year posttransplant [11]. Despite these promising results, a definitive study of ganciclovir or valganciclovir in PTLD prevention has not been done, and further data are needed to better elucidate the role of valganciclovir in PTLD prophylaxis.

Individuals with HIV infection can also develop severe clinical manifestations of EBV infection, including oral hairy leukoplakia and lymphoma. However, few studies have evaluated the role of antiviral therapy for EBV in HIV-infected individuals in the cART era. Previous studies by our group showed increased EBV shedding associated with uncontrolled HIV viremia [12]; more recent data suggest that persistence of CMV and EBV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of HIV-infected MSM is associated with slower decay of HIV DNA. These findings indicate that replicating herpesviruses may promote persistence of the HIV viral reservoir [13], and suggest a possible role for antiviral therapy in HIV-infected individuals. The role valganciclovir could play in the clinical management of HIV-infected patients in the ART era remains to be defined.

Most prior studies evaluating antiviral therapy for EBV-associated disease have considered multiple drugs simultaneously. However, in vitro experiments revealed that EBV tyrosine kinase has variable affinity for the antiherpetic antivirals [14]. In prior studies examining HHV-8, valacyclovir and famciclovir led to reductions of 18% and 30%, respectively [15], while valganciclovir reduced shedding frequency by 46% [7], suggesting that valganciclovir could play a role in treating complicated acute EBV infection and preventing PTLD.

Our study has several limitations. First, all study participants were selected based on their history of HHV-8 shedding. Individuals with high rates of oral HHV-8 shedding could have higher rates of EBV shedding than the general population, indicating the need for cautious extrapolation from this patient population. Second, all study participants were men, although natural history does not suggest that the outcome of EBV infection varies with sex. Third, the optimal dose of valganciclovir needed to prevent EBV-related disease is unclear. The induction phase of CMV treatment generally requires 900 mg of valganciclovir given twice daily; subsequent maintenance therapy requires only 900 mg daily. Because of the potential drug toxicities and lack of clinical benefit in this proof-of-concept study, we used the lower dose. A higher dose could possibly result in a greater viral load reduction, though any resulting benefit may be offset by additional toxicities and costs. Further studies are needed to compare different dosing strategies and to determine differential clinical benefit and toxicity profiles.

In summary, we found a substantial decrease in oral shedding of EBV when participants received once-daily valganciclovir compared with placebo, suggesting that valganciclovir may have utility as an important prophylactic or therapeutic agent for EBV-related disease.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers UL1TR000423 to J. Y., P30 AI027757 and P30 CA015704 to C. C., K24 AI071113 and P01 AI030731 to A. W.) and Roche Pharmaceuticals.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Niederman JC, Miller G, Pearson HA, Pagano JS, Dowaliby JM. Infectious mononucleosis. Epstein-Barr-virus shedding in saliva and the oropharynx. N Engl J Med 1976; 294:1355–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thorley-Lawson DA, Gross A. Persistence of the Epstein-Barr virus and the origins of associated lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:1328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balfour HH, Jr, Hokanson KM, Schacherer RM, et al. A virologic pilot study of valacyclovir in infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Virol 2007; 39:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gomyo H, Shimoyama M, Minagawa K, et al. Effective anti-viral therapy for hemophagocytic syndrome associated with B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44:1807–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hunt PW, Martin JN, Sinclair E, et al. Valganciclovir reduces T cell activation in HIV-infected individuals with incomplete CD4+ T cell recovery on antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2011; 203:1474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gill H, Hwang YY, Chan TS, et al. Valganciclovir suppressed Epstein Barr virus reactivation during immunosuppression with alemtuzumab. J Clin Virol 2014; 59:255–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Casper C, Krantz EM, Corey L, et al. Valganciclovir for suppression of human herpesvirus-8 replication: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torre D, Tambini R. Acyclovir for treatment of infectious mononucleosis: a meta-analysis. Scand J Infect Dis 1999; 31:543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evens AM, David KA, Helenowski I, et al. Multicenter analysis of 80 solid organ transplantation recipients with post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease: outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:1038–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Darenkov IA, Marcarelli MA, Basadonna GP, et al. Reduced incidence of Epstein-Barr virus-associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder using preemptive antiviral therapy. Transplantation 1997; 64:848–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Funch DP, Walker AM, Schneider G, Ziyadeh NJ, Pescovitz MD. Ganciclovir and acyclovir reduce the risk of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2005; 5:2894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Griffin E, Krantz E, Selke S, Huang ML, Wald A. Oral mucosal reactivation rates of herpesviruses among HIV-1 seropositive persons. J Med Virol 2008; 80:1153–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gianella S, Anderson CM, Var SR, et al. Replication of human herpesviruses is associated with higher HIV DNA levels during antiretroviral therapy started at early phases of HIV infection. J Virol 2016; 90:3944–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tung PP, Summers WC. Substrate specificity of Epstein-Barr virus thymidine kinase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1994; 38:2175–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cattamanchi A, Saracino M, Selke S, et al. Treatment with valacyclovir, famciclovir, or antiretrovirals reduces human herpesvirus-8 replication in HIV-1 seropositive men. J Med Virol 2011; 83:1696–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]