Antarctic vascular plants show restrictions in mesophyll CO2 conductance due to morphological leaf adaptations to deal with the harsh climate. Rubisco kinetic parameters, however, compensate by optimizing photosynthesis and carbon balance.

Keywords: Antarctic plants, leaf traits, mesophyll conductance, photosynthesis, Rubisco, temperature

Abstract

Particular physiological traits allow the vascular plants Deschampsia antarctica Desv. and Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. to inhabit Antarctica. The photosynthetic performance of these species was evaluated in situ, focusing on diffusive and biochemical constraints to CO2 assimilation. Leaf gas exchange, Chl a fluorescence, leaf ultrastructure, and Rubisco catalytic properties were examined in plants growing on King George and Lagotellerie islands. In spite of the species- and population-specific effects of the measurement temperature on the main photosynthetic parameters, CO2 assimilation was highly limited by CO2 diffusion. In particular, the mesophyll conductance (gm)—estimated from both gas exchange and leaf chlorophyll fluorescence and modeled from leaf anatomy—was remarkably low, restricting CO2 diffusion and imposing the strongest constraint to CO2 acquisition. Rubisco presented a high specificity for CO2 as determined in vitro, suggesting a tight co-ordination between CO2 diffusion and leaf biochemistry that may be critical ultimately to optimize carbon balance in these species. Interestingly, both anatomical and biochemical traits resembled those described in plants from arid environments, providing a new insight into plant functional acclimation to extreme conditions. Understanding what actually limits photosynthesis in these species is important to anticipate their responses to the ongoing and predicted rapid warming in the Antarctic Peninsula.

Introduction

Antarctica is the coldest, driest, and windiest continent on Earth, with mean summer air temperatures <0 °C in continental Antarctica and between 0 and 2 °C in Maritime Antarctica (Convey, 1996). The study of how organisms behave in this hostile habitat is of particular interest to unravel functional adaptations to extreme conditions (see Alberdi et al., 2002; Cavieres et al., 2016).

Deschampsia antarctica Desv. (Poaceae) and Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. (Caryophyllaceae) are the only two vascular plants naturally colonizing these harsh conditions, being distributed along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and its associated islands (Maritime Antarctica) down to Lazarev Bay on the north-west coast of Alexander Island (69°22.0'S, 71°50.7'W) (Convey et al., 2011). Although several differences have already been described between these two species in dealing with the Antarctic conditions (Pérez-Torres et al., 2007; Cavieres et al., 2016), the performance of both Antarctic vascular species relies on a robust CO2 assimilation machinery, including a high activation state of Rubisco and stromal fructose-1,6-biphosphatase (Pérez-Torres et al., 2006). Deschampsia antarctica is more abundant and widely distributed along the Antarctic Peninsula than C. quitensis (Smith, 2003), colonizing different habitats ranging from mineral to organic soils, and from dry to waterlogged areas. In contrast, C. quitensis seems to be less tolerant to extreme conditions, preferring sparsely vegetated and sheltered sites with moist, but well-drained mineral soils (Smith, 2003). Although both species exhibit CO2 assimilation rates similar to those of other herbaceous species from low-temperature environments such as alpine or arctic habitats (Chapin and Shaver, 1985; Körner, 2003), D. antarctica has a higher photosynthetic capacity than C. quitensis (Montiel et al., 1999; Xiong et al., 1999). Under laboratory conditions, D. antarctica and C. quitensis are able to maintain ~30% of their maximum photosynthetic rates at 0 °C, but both species display maximal CO2 assimilation rates at 13 °C and 19 °C, respectively (Edwards and Smith, 1988). These findings led Xiong et al. (1999) to suggest that current and future warming would be beneficial for the carbon assimilation of these two Antarctic plants.

Although some information has been accrued on the responses of the Antarctic plants to the combination of cold and high light, and to the effect of temperature on their photosynthetic performance, most of these data come from laboratory-grown plants. Field assessments on the mechanisms involved in the photosynthetic regulation, on the anatomical and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis, and whether these limitations change among populations exposed to different environmental conditions are fundamental to understand the functional adaptations that these species have evolved to withstand the Antarctic conditions. This knowledge will equally provide powerful insights to anticipate how these species might respond to climate change.

Leaf mesophyll conductance of CO2 (gm) and Rubisco kinetic parameters are two key players in carbon assimilation needed for a proper understanding of the photosynthetic performance under field conditions. The kinetic traits describing Rubisco functioning differ among species (e.g. Delgado et al., 1995; Kubien and Sage, 2008; Hermida-Carrera et al., 2016; Orr et al., 2016), with habitat-dependent variations in some parameters, mostly related to contrasting thermal environment, CO2 concentration, and water availability (Galmés et al., 2005, 2014a, 2016). Regarding gm, several studies have quantified the importance of leaf anatomical traits in determining gm and, consequently, the photosynthetic capacity of different plant species (Terashima et al., 2001; Tomás et al., 2013; Flexas et al., 2016), or within the same species but growing under different environmental conditions (Peguero-Pina et al., 2015a). Contrasting environmental conditions can induce changes in several leaf traits that affect gm (Evans et al., 1994; Kogami et al., 2001; Terashima et al., 2001). Differences in leaf anatomical traits and chloroplast ultrastructure have been reported for D. antarctica growing along the Maritime Antarctica (Jellings et al., 1983; Gielwanowska and Szczuka, 2005). Regarding C. quitensis, plants growing at higher latitudes have smaller and thicker leaves than those grown at lower latitudes, evidenced by a smaller leaf cross-section, with higher mesophyll thickness, narrower adaxial surface, and reduced epidermis thickness (Cavieres et al., 2016). Although these changes have been related to plastic responses to the Antarctic climate (Romero et al., 1999), it is not clear to what extent they may affect the photosynthetic performance of these plants. More specifically, do ultrastructural mesophyll traits induce changes in gm and other photosynthetic parameters affecting the carbon assimilation capacity in these Antarctic plant species?

The main objective of the present study was to evaluate in situ the photosynthetic performance of two natural populations of D. antarctica and C. quitensis located at different latitudes within the Maritime Antarctica. In particular, we analyzed the response of photosynthesis to varying measurement temperatures and the diffusive and biochemical constraints to CO2 assimilation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first field study thoroughly analyzing the responses and limitations of photosynthesis on these species.

Materials and methods

Study area and plant material

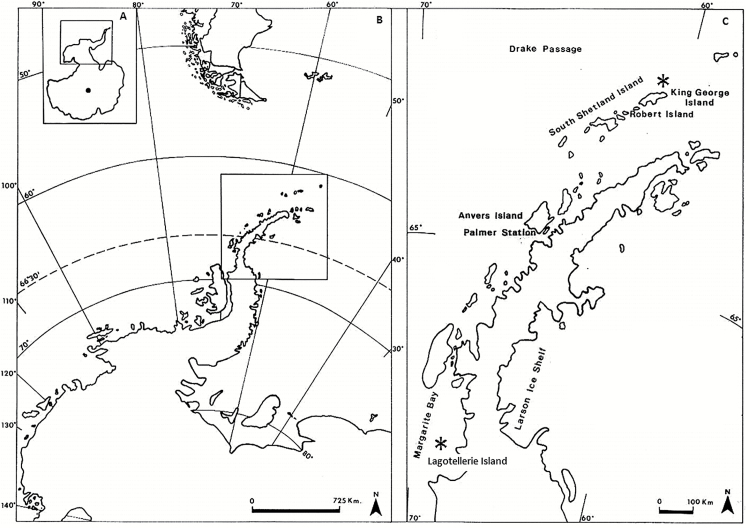

Two study sites were selected (Fig. 1): one located in King George Island (KGI), near to Henryk Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station (62°09'S, 58°28'W), and the other in Lagotellerie Island (LAG), in Marguerite Bay (67°53^20ʺS, 67°25ʹ30ʺW). These sites were selected based on the visual similarity of the vegetation, exposure, and elevation, as well as their distance from the coast. The sites are characterized by wide open and relatively flat areas (KGI) or terraces (LAG) covered by vegetation. In both sites, individuals of D. antarctica and C. quitensis (see Supplementary Fig. S1 at JXB online) were randomly selected, within an area of ~300 m2, for photosynthesis measurements and sampling of leaves during six sunny days in late January 2015 in LAG and during February 2015 in KGI.

Fig. 1.

The Antarctic continent (A), Antarctic Peninsula (B, inset from A), South Shetland Islands, and area of the Antarctic Peninsula (C, inset from B). Vascular plants from 62° to 67° South latitude, including the two study areas represented by an asterisk (*): King George Island (62°09'S, 58°28ʹW) and Lagotellerie Island (67°53ʹ20ʺS, 67°25ʹ30ʺW), Marguerite Bay (modified from Alberdi et al., 2002).

Climate

Precipitation in both sites falls mainly as snow. Annual precipitation, which occurs mostly during summer, is higher in the northernmost population (~1249 mm), while in Marguerite Bay it is ~360 mm (Turner et al., 2002). During summer, the day length in KGI is ~15 h, and the mean air temperature is 0.7 °C, with average maximum and minimum air temperature of 2.9 °C and –4.1 °C, respectively. In LAG, summer day length is ~17 h, with mean air temperature of –3.5 °C and average maximum and minimum of 1 °C and –10.9 °C, respectively (Utah State University Database; https://climate.usurf.usu.edu).

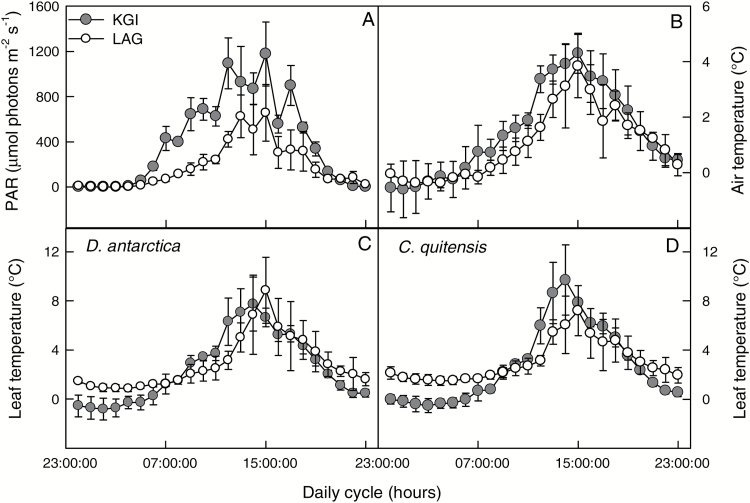

Daily microclimatic records of air temperature at 10 cm above ground level, leaf temperature, and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) were taken during 6 d in January 2015 (Fig. 2). According to these data, the daily integral of photosynthetic solar radiation in KGI was 30% greater than in LAG (Fig. 2A). Air temperature at KGI tended to be higher than at LAG during most of the daylight period (Fig. 2B). At both locations, leaf temperature of D. antarctica and C. quitensis was at least 2 °C above ambient temperature, reaching a maximum of ~10 °C (Fig. 2). Differences in leaf temperature between locations were evident during the night, where individuals of both species growing in LAG showed higher leaf temperature (~2 °C) compared with individuals from KGI (Fig. 2C, D). In contrast, during the day, there was a trend for higher leaf temperatures in KGI compared with LAG.

Fig. 2.

Diurnal course of photosynthetically active radiation (A), air temperature (B), and leaf temperature in D. antarctica (C) and C. quitensis (D) in King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG) between 17 and 22 January 17 2015. Values are means ± SE

Leaf gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence

Instantaneous gas exchange and Chl a fluorescence measurements (Li-6400XT, Li-6400-40 leaf chamber, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) were performed on a group of leaves (from a branch of C. quitensis or a tiller of D. antarctica), trying to cover all the IRGA’s chamber area and avoiding leaf overlap. When the leaf area was lower than the chamber area, a correction by actual leaf area inside the chamber was performed.

The response of net photosynthesis CO2 uptake (AN) to varying substomatal CO2 concentration (Ci) was studied with the so-called AN–Ci curves. All measurements were made at 1000 µmol photons m–2 s–1, air relative humidity of 40–50%, and at two leaf temperatures: 10 ºC and 15 ºC. These measurement temperatures corresponded to the maximal leaf temperatures recorded in the field (Fig. 2), and the average of optimal temperature for photosynthesis determined for these species in both populations, respectively (data not shown).

The AN–Ci curves were initiated by allowing the leaf to reach steady state (typically 20–30 min after clamping the leaf). Thereafter, AN–Ci curves were obtained at 11 different ambient CO2 concentrations (Cas) from 0 to 2000 μmol CO2 mol–1. Leaves were left to equilibrate at least 5 min at each CO2 concentration. Dark mitochondrial leaf respiration (Rdark) was obtained at pre-dawn at a Ca of 400 μmol CO2 mol–1 and the two measuring temperatures (10 ºC and 15 ºC). Leaf temperature was measured with a fine-wire thermocouple touching the abaxial surface for the group of leaves. Corrections for the leakage of CO2 into and out of the leaf chamber of the Li-6400 were applied to all gas exchange data, as described by Flexas et al. (2007).

The quantum efficiency of PSII-driven electron transport was determined using the equation: φPSII=(F 'm–Fs)/F 'm where Fs is the steady-state fluorescence in the light (PPFD 1000 μmol quanta m–2 s–1) and F 'm the maximum fluorescence obtained with a light-saturating pulse (8000 μmol quanta m–2 s–1). As φPSII represents the number of electrons transferred per photon absorbed by PSII, the electron transport rate (ETR) can be calculated as: ETR=φPSII×PPFD αβ, where PPFD is the photosynthetic photon flux density, α is the leaf absorptance, and β is the distribution of absorbed energy between the two photosystems, assumed to be 0.5. The leaf absorptance was directly measured in field-collected plants using a chlorophyll fluorescence system Imaging mini-PAM (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany). Successive illumination of the samples with red (R) and near infrared (NIR) light and the capture of each remission image allowed the calculation of leaf absorptance as follows: Abs=1–R/NIR. Leaf absorptance values were not significantly different between populations, with average values of 0.729 ± 0.02 for D. antarctica and 0.738 ± 0.02 for C. quitensis (mean ± SE, n=50).

The ratio of the electron transport rate and gross photosynthesis (ETR/AG) was calculated at a Ca of 400 μmol CO2 mol–1 air. Gross photosynthesis (AG) was calculated from the sum of the net CO2 assimilation rate (AN) and half of the mitochondrial respiration in the dark (Rdark).

Estimation of gm and Cc

Mesophyll conductance for CO2 (gm) was calculated from both combined gas-exchange and Chl a fluorescence measurements, and anatomical modeling. From the combined gas-exchange and Chl a fluorescence measurements, gm was calculated as in Harley et al. (1992): gm=AN/<Ci–{Γ*[ETR+8 (AN+RL)]/[ETR–4 (AN+RL)]}>, where AN and Ci were obtained from gas exchange measurements at saturating light. The non-photorespiratory CO2 evolution rate in the light (RL) was assumed to be half of Rdark, and the chloroplast CO2 compensation point (Γ*) was calculated according to Brooks and Farquhar (1985) from the Rubisco specificity factor (Sc/o) measured in vitro. Determination of gm was used to calculate the chloroplast CO2 concentration (Cc), converting AN–Ci curves into AN–Cc curves, as Cc=Ci –(AN/gm).

The maximum velocity of carboxylation (Vcmax) was derived from AN–Cc curves according to Farquhar et al. (1980) and using the kinetic constants for Rubisco determined for these species at the measurement temperatures (see below).

The approach of Tomás et al. (2013) was used for anatomical modeling of gm. In the field, the central portions of leaves were fixed in formaldehyde, acetic acid, and ethanol, and 4% glutaraldehyde for optical and transmission electron microscopy (JEM1200 EXII, Japan), respectively. Six to 10 micrographs were randomly selected to measure the mesophyll thickness; the mesophyll area exposed to the intercellular air space (Sm) to total leaf surface (S) area ratio (Sm/S); the chloroplast-exposed surface area to total surface area ratio (Sc/S); the chloroplast length (Lchl); the chloroplast thickness (Tchl); and the cell wall thickness (Tcw). All images were analyzed with image analysis software (ImageJ; Wayne Rasband/NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The one-dimensional gas diffusion model of Niinemets and Reichstein (2003) was employed to estimate the different leaf anatomical characteristics determining gm. The determinants of gm were divided between gas-phase conductance and the different components of the cellular phase conductances: the cell wall (lcw), the plasmalemma (lpl), and inside the cells through the cytosolic path (lcel,tot).

Rubisco kinetic characterization at varying temperature

The Rubisco Michaelis–Menten constant for CO2 under 21% O2 (Kcair) was determined in crude extracts obtained as detailed in Galmés et al. (2014a). Replicate measurements (n=3) were made using independent protein preparations from different individuals. To obtain the Rubisco carboxylase specific activity (kcatc), the maximum rate of carboxylation was extrapolated from the Michaelis–Menten fitted curve and divided by the number of Rubisco active sites in solution, quantified by [14C]CABP (2′-carboxyarabinitol-1, 5-bisphosphate) binding (Yokota and Canvin, 1985) as described in Galmés et al. (2013). The carboxylase catalytic efficiency was obtained as the ratio kcatc/Kcair.

Determination of the Rubisco specificity for CO2/O2 (Sc/o) at varying temperature

The Rubisco CO2/O2 specificity (Sc/o) was measured on purified extracts as in Gago et al. (2013), except that values were not normalized to those of wheat Rubisco. Measurements were performed at 5, 15, and 25 ºC, with 3–6 replicates per species and per assayed temperature. For comparative purposes, all Rubisco kinetic traits, including Sc/o, were also determined in wheat (Triticum aestivum ‘Cajerne’) at 25 ºC.

For all Rubisco assays, the pH of the assay buffers was accurately adjusted at each measurement temperature. The concentration of CO2 in solution in equilibrium with HCO3– was calculated assuming a pKa for carbonic acid of 6.31, 6.19, and 6.11 at 5, 15, and 25 ºC, respectively. The concentration of O2 in solution was assumed to be 400.5, 316.4, and 258.9 nmol ml–1 at 5, 15, and 25 ºC, respectively (Truesdale and Downing, 1954).

Temperature response of the Rubisco kinetic constants

The temperature response of the Rubisco kinetic parameters was fitted for each individual temperature response data set by an Arrhenius-type temperature response function:

| (1) |

where c is the scaling constant for the parameter, ΔHa (J mol−1) is the activation energy, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), and T (K) is the temperature. Equation 1 was fitted to the data by iteratively minimizing the sum of squares between the measured and predicted values of each kinetic parameter using the Microsoft Excel Solver function.

Statistical analyses

Fully factorial two-way ANOVAs were performed on each species to assess differences between populations and measurement temperatures. Differences between means were assessed by a posteriori Tukey test (P<0.05). These analyses were performed with the SPSS statistics 19.0 software package (IBM-software, New York, USA). A Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the anatomical derived gm and studied anatomical traits. Goodness of fit to saturation curves was assessed in: AN/gtot, AN/Cc, and AN/gm. All these analyses were done in Statistica 7.0 (Stat Soft Inc. Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Leaf carbon exchange in Antarctic plants at different measurement temperatures

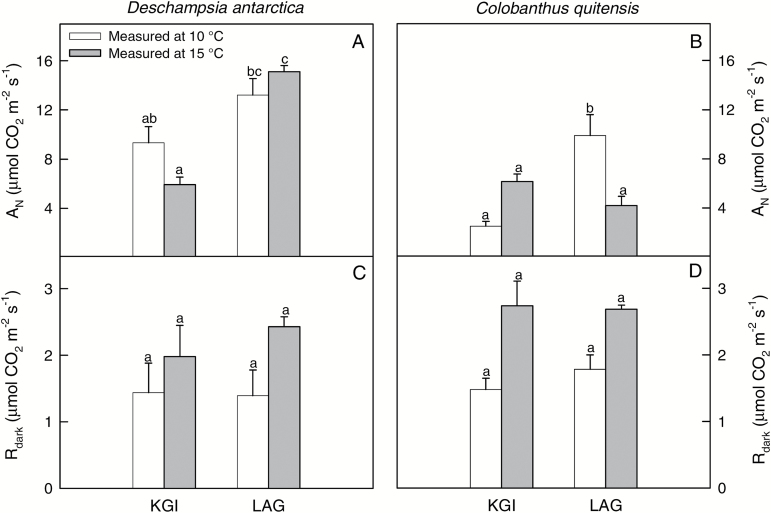

Plants from LAG exhibited higher net CO2 assimilation rates (AN) at ambient CO2 concentration than those from KGI, with no differences between measurement temperatures in the studied populations, although in both species the interaction between these two factors was significant (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Fig. S2). In D. antarctica, AN was higher in LAG at 15 °C (15.11 ± 0.51 µmol CO2 m–2 s–1) compared with KGI (5.93 ± 0.60 µmol CO2 m–2 s–1; Fig. 3A), but AN was similar across the two sites at 10 °C (~12 µmol CO2 m–2 s–1). In C. quitensis, the highest AN value was observed in LAG at 10 °C (9.88 ± 1.71 µmol CO2 m–2 s–1) and the lowest in KGI at 10 ºC (2.53 ± 0.37 µmol CO2 m–2 s–1; Fig. 3B). There were no differences in the dark respiration rate (Rdark) between populations or measurement temperatures (Fig. 3C, D; Supplementary Table S1). This indicates that the observed differences in AN were not due to differences in Rdark, but to differences in the photosynthetic process and its determinants.

Fig. 3.

The net photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate (AN) and dark respiration (Rdark) of D. antarctica (A, C) and C. quitensis (B, D) in King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG), measured at 10 °C (white bars) or 15 °C (gray bars). Values are means ± SE (n=5–7). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences for each species between populations and measurement temperature according to Tukey (P<0.05).

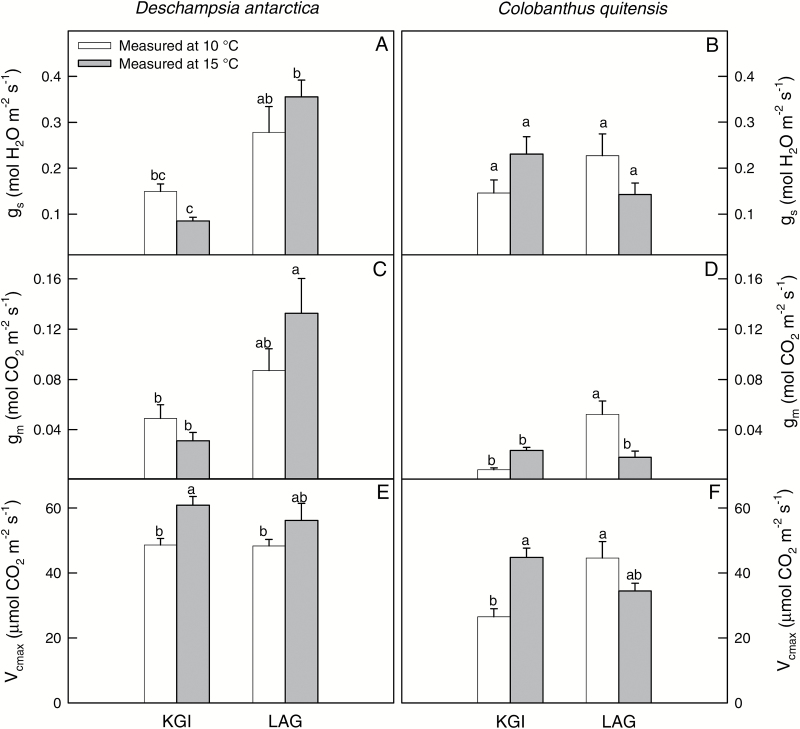

Diffusive limitations to photosynthesis

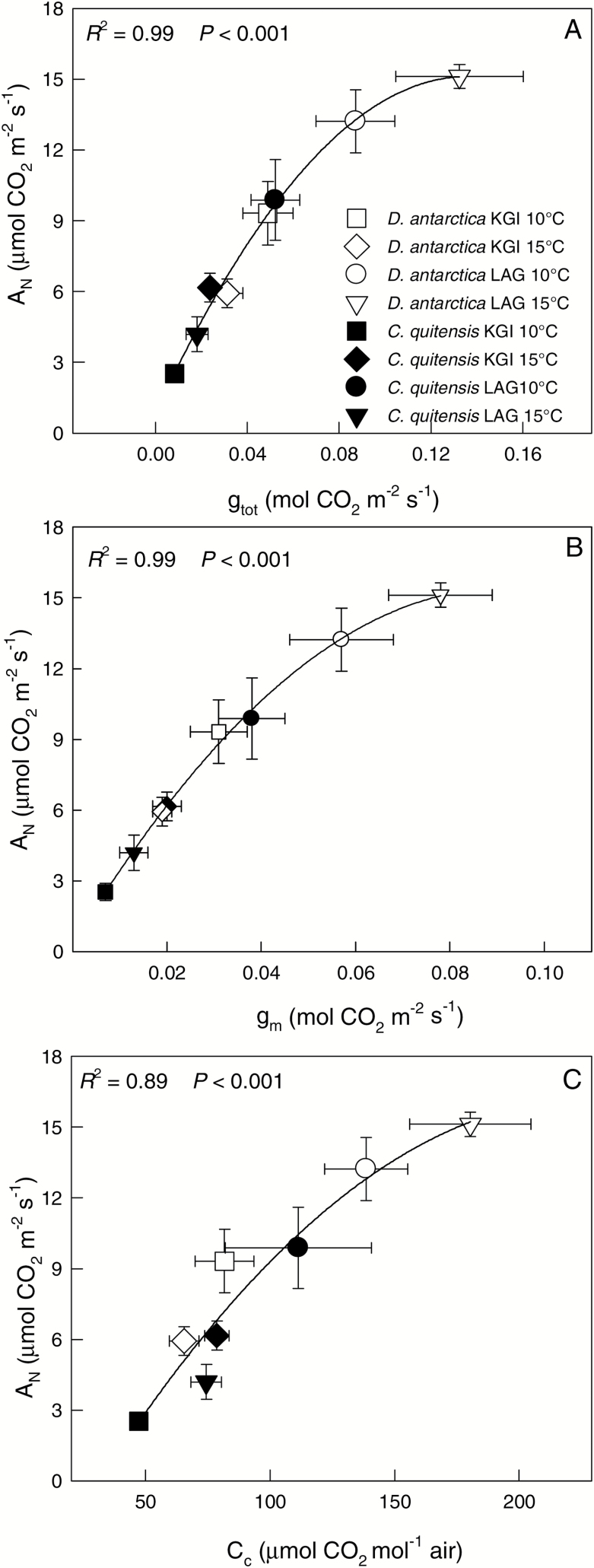

Stomatal (gs) and leaf mesophyll (gm) conductances for both species showed similar trends to those described for AN (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S1). Values of gs for D. antarctica ranged between 0.08 ± 0.01 mol H2O m–2 s–1 at KGI at 15 ºC and 0.35 ± 0.03 mol H2O m–2 s–1 in LAG at 15 ºC. For C. quitensis, gs varied from 0.14 ± 0.02 mol H2O m–2 s–1 in LAG at 15 ºC to 0.23 ± 0.03 mol H2O m–2 s–1 in KGI at 15 ºC (Fig. 4A, B). Estimated gm values were lower than those of gs, with the minimum value estimated in C. quitensis from KGI at 10 ºC (0.01 ± 0.01 mol CO2 m–2 s–1), and the highest in D. antarctica from LAG at 15 ºC (0.13 ± 0.02 mol CO2 m–2 s–1). The low gm determined low total leaf conductance to CO2 (gtot), which significantly correlated with AN (Fig. 5A). This indicates that the photosynthetic rates in the Antarctic vascular plants under field conditions were limited by diffusional components in general, and low gm in particular (Fig. 5B). The good correspondence between AN and the chloroplastic CO2 concentration (Cc) further confirms that carbon fixation in these species was constrained by low availability of CO2 at the carboxylation sites (Fig. 5C). In general, diffusion limitations to photosynthesis were more evident in C. quitensis (Figs 4, 5), which is consistent with the lowest CO2 assimilation rates found in this species (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 4.

The stomatal (A, B) and the leaf mesophyll (C, D) conductances, and the maximum rate of Rubisco carboxylation (E, F) of D. antarctica (left) and C. quitensis (right) in King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG), measured at 10 °C (white bars) or 15 °C (gray bars). Values are means ± SE (n=5–7). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between populations for each species and measurement temperature according to Tukey (P<0.05).

Fig. 5.

The relationship of (A) the total leaf conductance (gtot), (B) the leaf mesophyll conductance (gm), and (C) the chloroplast CO2 concentration (Cc) to the net photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate (AN) of D. antarctica (open circles) and C. quitensis (filled circles) in King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG). Goodness of fit with a saturation model is shown for both species and considering all populations and measurement temperatures together. Values are means ± SE (n=5–7).

Mesophyll conductance modeled from leaf anatomy

The studied populations of D. antarctica showed similar leaf anatomy, with the exception of the mesophyll thickness (Tmes), which was higher in plants from LAG, and the chloroplast surface area facing intercellular air spaces per leaf area (Sc/S), which was larger in plants from KGI (Table 1). No differences between populations were found in ultrastructural leaf characteristics (Supplementary Fig. S3) such as cell wall thickness (Tcw), average distance between chloroplasts (ΔLcyt), and their size (Lchl and Tchl). In addition, large numbers of organelles around chloroplasts were observed in both plant species (Supplementary Figs S3, S4). For C. quitensis, there were differences between populations in most of the anatomical parameters evaluated, except in Tmes and the chloroplast length (Lchl) (Table 1). In particular, C. quitensis plants from KGI exhibited higher Tcw, ΔLcyt, and chloroplast thickness (Tchl) than plants from LAG (Table 1). The contrasting anatomical traits between both populations of C. quitensis determined differences in gm modeled from leaf anatomy (0.013 ± 0.001 mol CO2 m–2 s–1 in KGI versus 0.039 ± 0.004 mol CO2 m–2 s–1 in LAG).

Table 1.

The mesophyll thickness between the two epidermal layers (Tmes), the cell wall thickness (Tcw), the average distance between chloroplasts (ΔLcyt), the chloroplast thickness (Tchl), the chloroplast length (Lchl), the CO2 transfer conductances across the intercellular air space (gias), the liquid phase (gliq), and the mesophyll conductance for CO2 (gm) calculated from leaf anatomical measurements, the mesophyll (Sm/S) and chloroplast (Sc/S) surface area facing intercellular air spaces per leaf area, for D. antarctica and C. quitensis from King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG)

| D. antarctica | C. quitensis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGI | LAG | KGI | LAG | |

| T mes (μm) | 101.03 ± 5.43 a | 136.27 ± 5.14 b | 322.29 ± 13.42 a | 290.77 ± 18.91 a |

| T cw (µm) | 0.26 ± 0.01 a | 0.22 ± 0.03 a | 0.35 ± 0.06 b | 0.21 ± 0.02 a |

| ΔLcyt (µm) | 0.68 ± 0.18 a | 0.3 ± 0.16 a | 0.53 ± 0.06 b | 0.05 ± 0.03 a |

| T chl (µm) | 2.96 ± 0.24 a | 3.58 ± 0.52 a | 5.12 ± 0.66 b | 1.64 ± 0.12 a |

| L chl (µm) | 4.40 ± 0.36 a | 5.48 ± 0.56 a | 5.32 ± 0.28 a | 5.92 ± 0.36 a |

| g ias (m s–1) | 0.046 ± 0.006 a | 0.031 ± 0.004 a | 0.013 ± 0.001 a | 0.019 ± 0.001 b |

| g liq (m s–1) | 0.0005 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0005 ± 0.0001 a | 0.0003 ± 0.0000 a | 0.0001 ± 0.0001 b |

| g m (mol m–2 s–1) | 0.022 ± 0.002 a | 0.023 ± 0.004 a | 0.013 ± 0.001 a | 0.039 ± 0.004 b |

| S m/S (m2 m–2) | 6.40 ± 0.75 a | 6.28 ± 0.51 a | 4.33 ± 0.48 a | 8.56 ± 0.53 b |

| S c/S (m2 m–2) | 2.24 ± 0.48 b | 1.16 ± 0.08 a | 2.06 ± 0.32 a | 4.42 ± 0.63 b |

Values are means ± SE (n=6–10).

Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between populations for each species (P<0.05).

In general, anatomy-based gm values were lower than those estimated in vivo by the method of Harley et al. (1992) (Table 1). It should be noted that anatomical measurements do not consider the different leaf temperatures recorded between populations (Fig. 2); therefore, the comparison with the ‘Harley’ gm should be treated with caution. Despite this limitation, some of the described trends for gm estimated by the method of Harley et al. (1992) were also found with the anatomy-based gm (compare Fig. 4D with Table 1). For example, C. quitensis from LAG at 10 ºC showed higher values compared with the KGI. In contrast, the higher ‘Harley’ gm found in D. antarctica from LAG compared with KGI (Fig. 4C) was not supported by the anatomical modeling of gm (Table 1).

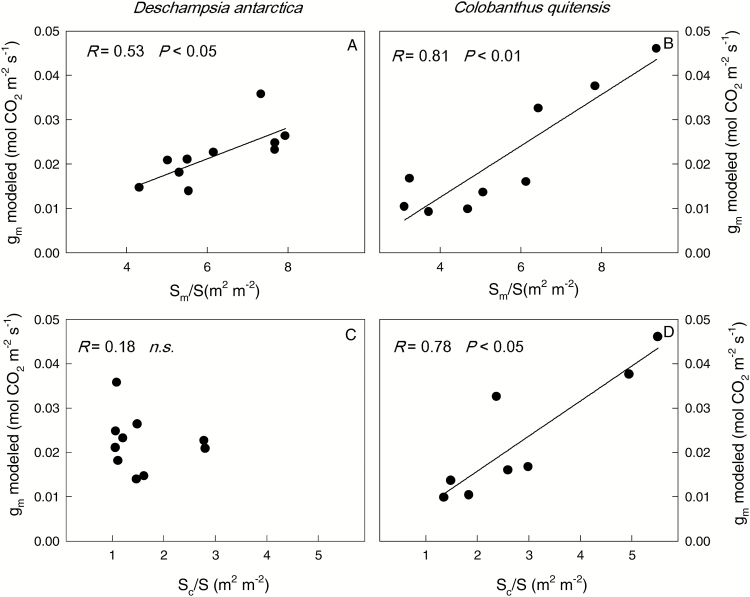

In C. quitensis, the mesophyll (Sm/S) and chloroplast (Sc/S) surface areas facing the intercellular air spaces per leaf area were significantly higher in LAG compared with KGI (Table 1), and the values of Sm/S and Sc/S correlated positively with gm modeled from leaf anatomy (Fig. 6). In D. antarctica, Sc/S but not Sm/S differed between populations, and only Sm/S but not Sc/S correlated with gm (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Correlations of the leaf mesophyll conductance modeled with anatomical parameters (gm modeled) with the mesophyll (Sm/S) and chloroplast (Sc/S) surface area facing intercellular air spaces per leaf area in D. antarctica (left) and C. quitensis (right). The Pearson correlation coefficient and the significance of the relationship are shown for each species considering both populations together. Values are means ± SE (n=3–5).

In both species, the CO2 transfer conductance across the liquid phase (gliq) was lower than that across the intercellular air space (gias) (Table 1), which yielded a low quantitative gm limitation by the intercellular air spaces (lias) (Table 2). Regarding the components of gliq: the cell wall (lcw), but mainly the cytoplasm and stroma (lcet,tot) limitations determined the low internal diffusion of CO2 observed in the Antarctic vascular plants.

Table 2.

Quantitative limitation analysis of the leaf mesophyll conductance to CO2 (gm) for D. antarctica and C. quitensis from King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG) due to different anatomical components of the diffusion pathway: intercellular spaces (lias), cell wall (lcw), plasmalemma (lpl), and inside the cell (lcel, tot)

| D. antarctica | C. quitensis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGI | LAG | KGI | LAG | |

| l ias (%) | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.7 ± 0.2 a | 2.5 ± 0.4 a | 4.6 ± 0.1 b |

| l cw (%) | 34.4 ± 1.3 a | 27.4 ± 2.1 b | 35.4 ± 5.4 a | 49.5 ± 6.2 a |

| l pl (%) | 2.3 ± 0.1 a | 2.3 ± 0.2 a | 2.0 ± 0.3 a | 3.3 ± 0.1 b |

| l cel, tot (%) | 62.3 ± 1.5 a | 68.4 ± 2.1 a | 59.8 ± 5.4 a | 42.5 ± 6.1 b |

Values are means ± SE (n=4–10).

Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between populations for each species (P<0.05).

Biochemical determinants of photosynthesis

The maximum rate of Rubisco carboxylation (Vcmax) increased with the measurement temperature in both plant species from KGI, but non-significant differences between measurement temperatures were found in plants from LAG (Fig. 4E, F). For all the range of AN–Cc curves, AN was linearly correlated to Cc (Supplementary Fig. S5), which impeded the estimation of the maximum rate of electron transport (Jmax).

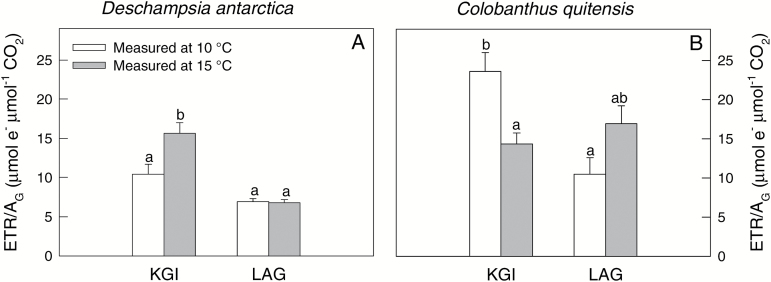

The ratio between the electron transport rate and gross CO2 assimilation rate (ETR/AG) which is used as a proxy of the amount of reducing power per unit of fixed CO2 (Flexas et al., 2002), varied between measurement temperatures and populations in both species (Fig. 7). In plants from KGI, the increase in the measurement temperature induced an increase in ETR/AG in D. antarctica but a decrease in C. quitensis. In plants from LAG, there were no temperature-driven changes in ETR/AG in either of the two species. The relationship between ETR/AG and Cc was highly significant and negative (Supplementary Fig. S6), indicative of enhanced photorespiration rates under low CO2 availability. Except for KGI at 15 ºC, C. quitensis exhibited higher values for ETR/AG—consistent with lower values for Cc.

Fig. 7.

The ratio of the electron transport rate and gross photosynthesis (ETR/AG) for D. antarctica (A) and C. quitensis (B) in King George (KGI) and Lagotellerie Island (LAG), measured at 10 °C (white bars) or 15 °C (gray bars). Values are means ± SE (n=5–7). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences for each species between populations and measurement temperatures according to Tukey (P<0.05).

Rubisco in vitro kinetic parameters and their temperature dependence

The affinity of Rubisco for CO2 measured as Kcair at 25 ºC was 18.7 ± 0.4 µM and 23.4 ± 1.8 µM for C. quitensis and D. antarctica, respectively (Table 3). The maximum rate of the carboxylase catalytic turnover (kcatc) was 3.76 ± 0.29 s–1 in C. quitensis and 4.10 ± 0.75 s–1 in D. antarctica. The carboxylase catalytic efficiency assessed by the kcatc/Kcair ratio ranged between 0.18 s–1 µM–1 and 0.20 s–1 µM–1 in both Antarctic species. At 25 ºC, the values of the Rubisco specificity factor (Sc/o) were 99.5 ± 4.8 mol mol–1 in D. antarctica and 97.1 ± 2.4 mol mol–1 in C. quitensis (Table 3).

Table 3.

In vitro Rubisco kinetic parameters and their temperature response in D. antarctica and C. quitensis

The Rubisco Michaelis–Menten constant affinity for CO2 under 21% O2 (Kcair), the maximum carboxylase catalytic turnover rate (kcatc), the carboxylase catalytic efficiency (kcatc/Kcair), and the specificity factor (Sc/o). For each parameter, the scaling constant (c) and the activation energy (ΔHa) are shown.

| Assay temperature | D. antarctica | C. quitensis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K c air (µM) | k cat c (s–1) | k cat c/Kcair (s–1 µM–1) | S c/o (mol mol–1) | K c air (µM) | k cat c (s–1) | k cat c/Kcair (s–1 µM–1) | S c/o (mol mol–1) | |

| 5 ºC | 10.9 ± 1.2 a* | 0.4 ± 0.1 a* | 0.04 ± 0.00 a | 167.5 ± 2.9 c | 6.9 ± 0.4 a* | 0.2 ± 0.1 a* | 0.03 ± 0.00 a | 172.4 ± 2.0 c |

| 15 ºC | 14.7 ± 0.8 a* | 1.4 ± 0.2 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 151.3 ± 4.5 b* | 11.1 ± 0.6 b* | 1.1 ± 0.1 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 b | 129.8 ± 3.7 b* |

| 25 ºC | 23.4 ± 1.8 b | 4.1 ± 0.8b | 0.18 ± 0.04 b | 99.5 ± 4.8 a | 18.7 ± 0.4 c | 3.8 ± 0.3 c | 0.20 ± 0.01 c | 97.1 ± 2.4 a |

| c | 14.5 ± 1.8 | 33.2 ± 0.8 | 18.4 ± 2.5 | –1.7 ± 0.6 | 17.1 ± 0.7 | 41.0 ± 2.7 | 20.9 ± 0.2 | –3.2 ± 0.5 |

| ΔHa (kJ mol–1) | 28.2 ± 4.4 | 78.8 ± 1.5* | 49.9 ± 5.6 | –15.9 ± 1.4 | 35.2 ± 1.6 | 98.3 ± 6.6* | 55.6 ± 0.5 | –19.3 ± 1.2 |

Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among assay temperatures in each species, and an asterisk denotes statistically significant differences between D. antarctica and C. quitensis for each assay temperature (P<0.05).

Values are means ± SE (n=3–6).

For comparative purposes, we also measured the kinetic parameters at 25 ºC in Rubisco from wheat (Triticum aesticum ‘Cajerne’). The values were as follows: Kcair=16.0 µM; kcatc=2.2 s−1; kcatc/Kcair=0.14 s–1 µM–1; Sc/o=101.1 mol mol–1.

Differences were observed in the temperature response of Rubisco between D. antarctica and C. quitensis (Table 3). For instance, D. antarctica presented higher values for Kcair than C. quitensis at 5 °C and 15 °C. Differences in kcatc between D. antarctica and C. quitensis were found only at 5 °C. In consequence, the Rubisco carboxylase catalytic efficiency did not differ between species at any of the assayed temperatures. Regarding Sc/o, differences between the two Antarctic plant species were observed only at 15 ºC, where D. antarctica presented higher values than C. quitensis (P<0.05).

The differences in the temperature response of Rubisco resulted in a trend for higher absolute values of the energy of activation (ΔHa) of the different kinetic parameters in C. quitensis, although significant differences between both species were only observed in ΔHa of kcatc (78.8 ± 1.5 kJ mol–1 in D. antarctica versus 98.3 ± 6.6 kJ mol–1 in C. quitensis).

Discussion

The leaf anatomical and biochemical traits described here for the Antarctic vascular plants growing at different latitudes within Antarctica and their implications on the photosynthetic performance of these species constitute new insights into the plant functional responses to cold conditions. While ultrastructural traits of the leaf mesophyll restricted CO2 transfer and limited the photosynthetic capacity of the two Antarctic vascular plants, the kinetic traits of Rubisco, characterized by high affinity for CO2 and relative high values for kcatc, seem crucial to optimize carbon assimilation despite the restrictions of CO2 transport inside the leaf. The former suggests an important functional adaptation that, together with other traits (Cavieres et al., 2016), allows D. antarctica and C. quitensis to survive and grow in the harsh climate conditions of the Antarctica. As these two Antarctic species differ in their habitat requirements, plant morphology, leaf anatomy, and photosynthetic optimum temperature (Cavieres et al., 2016), an interspecific comparison was not considered here, except for Rubisco kinetic parameters.

Leaf mesophyll conductance to CO2 limits carbon assimilation in Antarctic plants

This is the first study assessing gm in Antarctic vascular plants, and how changes in the ultrastructure of the mesophyll affect gm, and hence the carbon acquisition in these species. According to our results, the range of gm values and the gm/gs ratio of these plant species are among the lowest reported so far for higher plant species (De Lucía et al., 2003; Flexas et al., 2009, 2014; Tomás et al., 2013; Peguero-Pina et al., 2015a). Under certain conditions, gm can be the most significant photosynthetic limitation (Flexas et al., 2012; Tomás et al., 2013; Galmés et al., 2014a; Niinemets and Keenan, 2014; Carriquí et al., 2014; Peguero-Pina et al., 2015a, b). As the photosynthetic rates of the Antarctic vascular plants were highly correlated with gm (Fig. 5B), this factor seems to be the main constraint for the photosynthetic process in these plant species in the field. Positive correlations between AN and gm have been previously reported (e.g. Evans and Loreto, 2000; Warren, 2008), and recent meta-analyses suggest that gm is also associated with the structure of leaves, determining the diffusion limitations of photosynthesis (Niinemets and Sack, 2006; Warren, 2008). Thus, our results highlight that morphoanatomical leaf characteristics regulating gm are key determinants of the photosynthetic functioning in the two Antarctic vascular plant species.

Large differences in gm have been shown both between and within species with different leaf forms and habits (e.g. Flexas et al., 2008; Warren, 2008). The low gm found in the Antarctic vascular plants in the field seems to be related to leaf anatomical traits that affect CO2 diffusion across the intercellular air space (Table 1), especially with the limitations associated with cell walls, cytoplasm, and stroma (Table 2). The leaf mesophyll diffusion limitations were especially evident in C. quitensis, which is consistent with the low photosynthetic rate of this species and with the high values of ETR/AG (Fig. 7), indicative of enhanced photorespiration rates. Higher leaf mesophyll thickness is commonly associated with a greater number of leaf mesophyll cell layers (Niinemets et al., 2009). In C. quitensis, the highest leaf mesophyll thickness was accompanied by the largest area of leaf mesophyll exposed to intercellular air space (Sm), and thus the greatest Sm to total leaf surface area ratio (Sm/S) (Table 1). Provided that the numbers of chloroplasts are similar in mesophyll cells, a larger Sm/S also implies a greater ratio between the chloroplast-exposed surface area and the total surface area (Sc/S) (Terashima et al., 2005, 2006). As a larger Sc/S implies more parallel pathways for CO2 liquid-phase diffusion, gm correlates positively with Sc/S (Fig. 6). Actually, higher leaf density has been associated with reduced gas-phase volume, and smaller and more densely packed leaf mesophyll cells with thicker cell walls (Niinemets, 1999; Niinemets and Sack, 2006). Such modifications could reduce the liquid-phase diffusion conductance and gm (Terashima et al., 2005; Evans et al., 2009). In addition, the observed differences in gm between both populations of C. quitensis can be partially attributed to the variation in other leaf anatomical traits such as Tcw, ΔLcyt, and Tchl (Table 1). Specifically, the cell wall and the resistances imposed by the cytoplasm and stroma exerted the highest limitations in the gm (Table 2). Further, as was noted above, Sm/S and Sc/S are two of the most important anatomical traits influencing gm (Tosens et al., 2012; Peguero-Pina et al., 2012; Carriquí et al., 2014).

Anatomical characteristics could not be the only explanation for the observed differences in gm, as those were also found between measurement temperatures in plants growing in LAG (Fig. 4C, D). It seems likely that some (not yet fully understood) biochemical components of gm could be involved in the regulation of gm. Among them, carbonic anhydrase (CAs) (Fabre et al., 2007) and aquaporins (AQPs) (Terashima and Ono, 2002) have been shown to modify gmin vivo in response to varying measurement temperatures. The discrepancy between gm estimates based on anatomical measurements and those based on conventional gas-exchange methods suggests the existence of these facilitating mechanisms for CO2 diffusion. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the activity and abundance of these proteins in Antarctic vascular plants, and thus we cannot draw any general conclusion on this issue.

The anatomical features of the Antarctic species have been regarded as adaptive responses to the harsh climate conditions of Antarctica (Cavieres et al., 2016). Among them, the large number of organelles (mitochondria or peroxisomes) around the chloroplasts in both Antarctic species (Supplementary Figs S3, S4) have been suggested as facilitators for the CO2 exchange between respiration and photorespiration processes (Gielwanoeska and Szczuka, 2005). In addition, both species have xeromorphic leaf characteristics (Nobel, 1980; Vieira and Mantovani, 1995; Romero et al., 1999), which are related to the water limitations due to the low temperature and strong winds that characterize the Antarctic climate (Smith, 1993). Some features, such as the presence of two bundle sheaths in leaf vascular bundles (mestome), of D. antarctica have been associated with an adaptation to high radiation in order to optimize photosynthesis and water use efficiency (WUE) (Pyykkö, 1966). Evert et al. (1985) suggested that the mestome functions as a leaf endodermis, limiting apoplastic movement of water across the mesophyll. This trait, along with a high stomatal density and leaf mass area, confer a high capacity to control water loss on D. antarctica (Vieira and Mantovani, 1995; Xiong et al., 2000; Alberdi et al., 2002). Decreased water movement across the leaf mesophyll could be advantageous to avoid heat loss in cold environments, being an important adaptation for these habitats (Sage, 2001). These characteristics are consistent with the low gm values determined in the present study using both gas-exchange/fluorescence and anatomical methods.

The low gm values resulted in low gtot values, and therefore low Cc. According to our results, AN was highly correlated with gm, gtot, and Cc (Fig. 5), confirming the predominant role of leaf CO2 diffusion in the photosynthetic performance of Antarctic plant species. In this sense, reduced photosynthesis, due to low gm, seems to be the penalty of structurally robust leaves that the Antarctic plant species have to pay to survive in extremely stressful conditions.

Rubisco performance alleviates the low mesophyll conductance

The Rubisco kinetic parameters, and their temperature response, have been related to species differences in the photosynthetic performance under varying conditions (Galmés et al., 2014a, 2015, 2016; Sharwood et al., 2016). The temperature dependence of Rubisco kinetics revealed some differences between the two Antarctic angiosperm species. In particular, the energy of activation (ΔHa) for kcatc was higher in C. quitensis compared with D. antarctica, indicative of higher thermal sensitivity (Table 3). The values for ΔHa of kcatc in the two Antarctic species are among the highest in Streptophyta, and do not support the reported trend (see compilation by Galmés et al., 2015) that the Rubisco enzymes of C3 species adapted to cool habitats have a lower plastic response to temperature changes compared with Rubisco of C3 species from warm environments. The molecular and biochemical causes of this apparent discrepancy, already observed in other species from cool habitats such as Atriplex glabriuscula (Badger and Collatz, 1977), are unknown and should be explored in depth. In contrast, the high values for both Sc/o and ΔHa of kcatc observed in the Antarctic species are in accordance with the transition state theory of Tcherkez et al. (2006).

In fact, the values of Sc/o measured at 25 ºC in both Antarctic plants (Table 3) are among the highest values reported so far for higher plant species (e.g. Galmés et al., 2005; Orr et al., 2016). We note that for comparative purposes between data sets, we also measured Rubisco kinetic parameters in wheat at 25 ºC (shown in the footnotes of Table 3) and the obtained values were similar to previous data (e.g. Galmés et al., 2005; Prins et al., 2016; Orr et al., 2016). Regarding Kcair at 25 ºC, both Antarctic plants, but in particular D. antarctica, presented values comparable with those reported for species adapted to xeric environments (Galmés et al., 2014a). Notably, despite their high affinity for CO2, Rubisco from the Antarctic plant species retained high kcatc, similar to species closely related to D. antarctica such as Poa arctica and Poa pratensis (Sage, 2002). The high kcatc leads to values for the carboxylase catalytic efficiency (kcatc/Kcair) higher than those reported for species from xeric habitats (Galmés et al., 2014a). Further, at 15 ºC (a temperature similar to the maximal diurnal leaf temperature recorded in the field; Fig. 2), Rubisco from both Antarctic plants increased the specificity for CO2 to levels similar to that reported for xeromorphic species (Galmés et al., 2005).

Although it has been suggested that the selective pressures for greater CO2 affinity for Rubisco have been high in species adapted to high temperature and low soil water availability (Galmés et al., 2005, 2014a), there is also evidence that in cold environments the selective pressures may favor Rubisco with higher kcatc (Sage, 2002; Yamori et al., 2009). Interestingly, the Antarctic species have evolved under both dry and cold conditions, and here we found that their Rubiscos show a high affinity for CO2 and retain high kcatc. The high Sc/o in the Antarctic plants is additional evidence in favor of the hypothesis that CO2 limitations shaped the evolution of their Rubisco kinetics (e.g. Raven, 2000; Young et al., 2012; Galmés et al., 2014b). In the case of the Antarctic plants, the low availability of CO2 at the sites of carboxylation is driven by adaptive anatomical traits to resist the extreme climatic conditions of low temperature and strong winds. It has been demonstrated that under conditions that promote drought, higher Sc/o reduces ribulose bisphosphate (RuBP) oxygenation and favors the carboxylase reaction (Galmés et al., 2005). Thus, it seems likely that the anatomical features that determine a low CO2 diffusion in these species are partially counterbalanced by a highly efficient Rubisco. The concentration of active Rubisco, calculated from Vcmax=kcatc×[active Rubisco sites], was notably high in both Antarctic species at 15 ºC: ~44.57 ± 1.9 µmol m–2 and 42.31 ± 2.84 µmol m–2 in D. antarctica and C. quitensis, respectively. Although these data should be confirmed by direct measurements in leaf extracts, they suggest that the decrease in kcatc at low temperatures is compensated by increased amount of [active Rubisco sites], following trends already reported in other species (e.g. Yamori et al., 2005, 2006).

The high Sc/o and low Kcair, as well as the constitutive low gm of Antarctic plants, are not their unique traits, resembling those documented for drought-adapted species. The presence of bundle sheaths found in D. antarctica and also in C. quitensis (Vieira and Mantovani, 1995) is a characteristic of plants from xeric climates (Sage, 2001). In addition, Montiel et al. (1999) reported remarkably high values of instantaneous WUE in D. antarctica, more typical of C4 and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) species than of C3 species. The high WUE of D. antarctica is likely to be related to the diffusive and biochemical determinants identified in the present study.

Concluding remarks

The present study provides new field data on the photosynthetic performance and diffusive and biochemical limitations of the two Antarctic plants. This work incorporates leaf anatomical traits related to CO2 assimilation and increases the range of knowledge of the diversity of Rubisco kinetics parameters in two relevant species.

The ultrastructural traits of the leaf mesophyll in field-grown Antarctic plants ultimately restricted the CO2 leaf transfer capacity and limited the photosynthetic capacity of these species. Under the cold and dry climate conditions of the Antarctica, the high Rubisco affinity for CO2 and relatively high values for kcatc seem crucial to optimize carbon assimilation. Overall, these results constitute new insights regarding the functional adaptations to highly stressful conditions in plants and the properties that enable the distribution and abundance of vascular plants in Antarctica. Considering the strong climate changes experienced in the Antarctic Peninsula that include rapid warming during the last decades, and a pause of that warming during recent years (Turner et al., 2016), the next challenge should be to assess the effect of different durations of long-term exposure to warmer temperatures on the photosynthetic performance of D. antarctica and C. quitensis.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. ANOVA of the effects of populations, measurement temperature, and their interaction.

Fig. S1. Deschampsia antarctica (left) and Colobanthus quitensis (right).

Fig. S2. The response of the net photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate (AN) to varying internal CO2 concentration (Ci).

Fig. S3. Transverse section of the mesophyll and mesophyll cells of D. antarctica.

Fig. S4. Transverse section of the mesophyll and mesophyll cells of C. quitensis.

Fig. S5. The response of the net photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate (AN) to varying chloroplast CO2 concentration (Cc).

Fig. S6. The relationship between electron transport rate and gross photosynthesis ratio (ETR/AG) and CO2 concentration at the site of carboxylation (Cc).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by The National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FONDECYT 11130332), The Associative Research Program of CONICYT (CONICYT-PIA ART-1102), The Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH AN-02-12 and FI_02-13), and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (AGL2009-07999 and AGL2013-42364R awarded to JG). LAC acknowledge funds from F ICM P05-02 and PFB-023 supporting the Institute of Ecology and Biodiversity (IEB). The authors thank Dr Charles L. Guy (University of Florida) for English editing and help with grammar. Permits for entrance and plant collection in the ASPA 128 and 115 were provided by INACH.

References

- Alberdi M, Bravo LA, Gutiérrez A, Gidekel M, Corcuera LJ. 2002. Ecophysiology of Antarctic vascular plants. Physiologia Plantarum 115, 479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger MR, Collatz GJ. 1977. Studies on the kinetic mechanism of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase and oxygenase reactions, with particular reference to the effect of temperature on kinetic parameters. Carnegie Institute of Washington Yearbook 76, 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD. 1985. Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta 165, 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriquí M, Cabrera HM, Conesa MÀ, et al. 2015. Diffusional limitations explain the lower photosynthetic capacity of ferns as compared with angiosperms in a common garden study. Plant, Cell and Environment 38, 448–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavieres LA, Sáez P, Sanhueza C, Sierra-Almeida A, Rabert C, Corcuera LJ, Bravo LA. 2016. Ecophysiological traits of Antarctic vascular plants: their importance in the responses to climate change. Plant Ecology 217, 343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin FS, III, Shaver GR. 1985. Arctic. In: Chabot BF, Mooney HA, eds. Physiological ecology of North American plant communities. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 16–40. [Google Scholar]

- Convey P. 1996. The influence of environmental characteristics on life history attributes of Antarctic terrestrial biota. Biological Reviews 7, 191–225. [Google Scholar]

- Convey P, Hopkins D, Roberts S, Tyler A. 2011. Global southern limit of flowering plants and moss peat accumulation. Polar Research 30, 8929. [Google Scholar]

- De Lucia E, Whitehead D, Clearwater MJ. 2003. The relative limitation of photosynthesis by mesophyll conductance in cooccurring species in a temperate rainforest dominated by conifer Dacrydium cuperessinum. Functional.Plant Biology 30, 1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado E, Medrano H, Keys AJ, Parry MAJ. 1995. Species variation in Rubisco specificity factor. Journal of Experimental Botany 46, 1775–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JA, Smith RL. 1988. Photosynthesis and respiration of Colobanthus quitensis and Deschampsia antarctica from the maritime Antarctica. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 81, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Setchell BA, Hudson GS. 1994. The relationship between CO2 transfer conductance and leaf anatomy in transgenic tobacco with a reduced content of Rubisco. Functional Plant Biology 21, 475–495. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Loreto F. 2000. Acquisition and diffusion of CO2 in higher plant leaves. In: Leegood RC, Sharkey TD, von Caemmerer S, eds. Photosynthesis: physiology and metabolism. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 321–351. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I. 2009. Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2235–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evert RF, Botha CEJ, Mierzwa RJ. 1985. Free-space marker studies on the leaf of Zea mays L. Protoplasma 126, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre N, Reiter IM, Becuwe-Linka N, Genty B, Rumeau D. 2007. Characterization and expression analysis of genes encoding α and β carbonic anhydrases in Arabidopsis. Plant, Cell and Environment 30, 617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C 3 species. Planta 149, 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barbour MM, Brendel O, et al. 2012. Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Science 193, 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Barón M, Bota J, et al. 2009. Photosynthesis limitations during water stress acclimation and recovery in the drought-adapted Vitis hybrid Richter-110 (V. berlandieri×V. rupestris). Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2361–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Bota J, Escalona J, Sampol B, Medrano H. 2002. Effects of drought on photosynthesis in grapevines under field conditions: an evaluation of stomatal and mesophyll limitations. Functional Plant Biology 29, 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Diaz-Espejo A, Berry JA, et al. 2007. Analysis of leakage in IRGA’s leaf chambers of open gas exchange systems: quantification and its effects in photosynthesis parameterization. Journal of Experimental Botany 58, 1533–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Díaz-Espejo A, Conesa MA, et al. 2016. Mesophyll conductance to CO2 and Rubisco as targets for improving intrinsic water use efficiency in C3 plants. Plant, Cell and Environment 39, 965–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Díaz-Espejo A, Gago J, Gallé A, Galmés J, Gulías J, Medrano H. 2014. Photosynthetic limitations in Mediterranean plants: a review. Environmental and Experimental Botany 103, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Ribas-Carbó M, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmés J, Medrano H. 2008. Mesophyll conductance to CO2: current knowledge and future prospects. Plant, Cell and Environment 31, 602–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago J, Coopman RE, Cabrera HM, et al. 2013. Photosynthesis limitations in three fern species. Physiologia Plantarum 149, 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Andralojc PJ, Kapralov MV, et al. 2014b. Environmentally driven evolution of Rubisco and improved photosynthesis and growth within the C3 genus Limonium (Plumbaginaceae). New Phytologist 203, 989–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Flexas J, Keys AJ, et al. 2005. Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment 28, 571–579. [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Hermida-Carrera C, Laanisto L, Niinemets Ü. 2016. A compendium of temperature responses of Rubisco kinetic traits: variability among and within photosynthetic groups and impacts on photosynthesis modeling. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 5067–5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Andralojc PJ, Conesa MÀ, Keys AJ, Parry MA, Flexas J. 2014a. Expanding knowledge of the Rubisco kinetics variability in plant species: environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant, Cell and Environment 37, 1989–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Kapralov MV, Copolovici LO, Hermida-Carrera C, Niinemets Ü. 2015. Temperature responses of the Rubisco maximum carboxylase activity across domains of life: phylogenetic signals, trade-offs, and importance for carbon gain. Photosynthesis Research 123, 183–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés J, Perdomo JA, Flexas J, Whitney SM. 2013. Photosynthetic characterization of Rubisco transplantomic lines reveals alterations on photochemistry and mesophyll conductance. Photosynthesis Research 115, 153–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielwanowska I, Szczuka E. 2005. New ultrastructural features of organelles in leaf cells of Deschampsia antarctica Desv. Polar Biology 28, 951–955. [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD. 1992. Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiology 98, 1429–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermida-Carrera C, Kapralov MV, Galmés J. 2016. Rubisco catalytic properties and temperature response in crops. Plant Physiology 171, 2549–2561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellings AJ, Usher MB, Leech RM. 1983. Variation in the chloroplast to cell area index in Deschampsia antarctica along a 16 degrees latitudinal gradient. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 61, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kogami H, Hanba YT, Kibe T, Terashima I, Masuzawa T. 2001. CO2 transfer conductance, leaf structure and carbon isotope composition of Polygonum cuspidatum leaves from low and high altitudes. Plant, Cell and Environment 24, 529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Körner C. 2003. Alpine plant life: functional plant ecology of high mountain ecosystems. 2nd edn Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kubien DS, Sage RF. 2008. The temperature response of photosynthesis in tobacco with reduced amounts of Rubisco. Plant, Cell and Environment 31, 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montiel P, Smith A, Keiller D. 1999. Photosynthetic responses of selected Antarctic plants to solar radiation in the southern maritime Antarctic. Polar Research 18, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü. 1999. Research review. Components of leaf dry mass per area—thickness and density—alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytologist 144, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets U, Díaz-Espejo A, Flexas J, Galmés J, Warren CR. 2009. Role of mesophyll diffusion conductance in constraining potential photosynthetic productivity in the field. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 2249–2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Keenan TF. 2014. Photosynthetic responses to stress in Mediterranean evergreens: mechanisms and models. Environmental and Experimental Botany 103, 24–41. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Reichstein M. 2003. Controls on the emission of plant volatiles through stomata: a sensitivity analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research 108, 4211. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Sack L. 2006. Structural determinants of leaf light-harvesting capacity and photosynthetic potentials. In: Esser K, Lüttge U, Beyschlag W, Murata J, eds. Progress in botany. Berlin: Springer: 385–419. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. 1980. Leaf anatomy and water use efficiency. In: Turner NC, Kramer PJ. eds. Adaptation of plant to water and high temperature stress. New York: Wiley, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Orr DJ, Alcântara A, Kapralov MV, Andralojc PJ, Carmo-Silva E, Parry MA. 2016. Surveying rubisco diversity and temperature response to improve crop photosynthetic efficiency. Plant Physiology 172, 707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Flexas J, Galmés J, et al. 2012. Leaf anatomical properties in relation to differences in mesophyll conductance to CO2 and photosynthesis in two related Mediterranean Abies species. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 2121–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Sancho-Knapik D, Flexas J, Galmés J, Niinemets Ü, Gil-Pelegrín E. 2015a. Light acclimation of photosynthesis in two closely related firs (Abies pinsapo Boiss. and Abies alba Mill.): the role of leaf anatomy and mesophyll conductance to CO2. Tree Physiology 36, 300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Sisó S, Fernández-Marín B, Flexas J, Galmés J, García-Plazaola JI, Niinemets Ü, Sancho-Knapik D, Gil-Pelegrín E. 2015b. Leaf functional plasticity decreases the water consumption without further consequences for carbon uptake in Quercus coccifera L. under Mediterranean conditions. Tree Physiology 36, 356–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Torres E, Bascuñán L, Sierra-Almeida A, Bravo LA, Corcuera LJ. 2006. Robustness of activity of Calvin cycle enzymes after high light and low temperature conditions in Antarctic vascular plants. Polar Biology 29, 909–916. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Torres E, Bravo LA, Corcuera LJ, Johnson GN. 2007 Is electron transport to oxygen an important mechanism in photoprotection? Contrasting responses from Antarctic vascular plants. Physiologia Plantarum 130, 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Prins A, Orr D, Andralojc P, et al. 2016. Rubisco catalytic properties of wild and domesticated relatives provide scope for improving wheat photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 1827–1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkö M. 1966. The leaf anatomy of East Patagonian xeromorphic plants. Annales Botanici Fennici 3, 453–622. [Google Scholar]

- Raven JA. 2000. Land plant biochemistry. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 355, 833–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero M, Casanova A, Iturra G, Reyes A, Montenegro G, Alberdi M. 1999. Leaf anatomy of Deschampsia antarctica (Poaceae) from the Maritime Antarctic and its plastic response to changes in the growth conditions. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural 72, 411–425. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2001. Environmental and evolutionary preconditions for the origin and diversification of the C4 photosynthetic syndrome. Plant Biology 3, 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2002. Variation in the kcat of Rubisco in C3 and C4 plants and some implications for photosynthetic performance at high and low temperature. Journal of Experimental Botany 53, 609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharwood RE, Ghannoum O, Kapralov MV, Gunn LH, Whitney SM. 2016. Temperature responses of Rubisco from Paniceae grasses provide opportunities for improving C3 photosynthesis. Nature Plants 2, 16186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RIL. 1993. Dry coastal ecosystems of Antarctica. In: van der Maarel E, ed. Ecosystems of the world. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RIL. 2003. The enigma of Colobanthus quitensis and Deschampsia antarctica in Antarctica. In: Huiskes AHL, Gieskes WWC, Rozema J, Schorno RML, van der Vies SM, Wolff WJ, eds. Antarctic biology in a global context. Leiden: Backhuys Publishers, 234–239. [Google Scholar]

- Tcherkez GG, Farquhar GD, Andrews TJ. 2006. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 103, 7246–7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Araya T, Miyazawa S, Sone K, Yano S. 2005. Construction and maintenance of the optimal photosynthetic systems of the leaf, herbaceous plant and tree: an eco-developmental treatise. Annals of Botany 95, 507–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tazoe Y, Vyas P, Yano S. 2006. Irradiance and phenotype: comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Miyazawa SI, Hanba YT. 2001. Why are sun leaves thicker than shade leaves? Consideration based on analyses of CO2 diffusion in the leaf. Journal of Plant Research 114, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Ono K. 2002. Effects of HgCl2 on CO2 dependence of leaf photosynthesis: evidence indicating involvement of aquaporins in CO2 diffusion across the plasma membrane. Plant and Cell Physiology 43, 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás M, Flexas J, Copolovici L, et al. 2013. Importance of leaf anatomy in determining mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2 across species: quantitative limitations and scaling up by models. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 2269–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T, Niinemets U, Vislap V, Eichelmann H, Castro Díez P. 2012. Developmental changes in mesophyll diffusion conductance and photosynthetic capacity under different light and water availabilities in Populus tremula: how structure constrains function. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 839–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truesdale GA, Downing AL. 1954. Solubility of oxygen in water. Nature 173, 1236. [Google Scholar]

- Turner T, Lachlan-Cope A, Marshall GJ, Morris EM, Mulvaney R, Winter W. 2002. Spatial variability of Antarctic Peninsula net surface mass balance. Journal of Geophysical Research 107, 4173. [Google Scholar]

- Turner J, Lu H, White I, et al. 2016. Absence of 21st century warming on Antarctic Peninsula consistent with natural variability. Nature 535, 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira RC, Mantovani A. 1995. Leaf anatomy of Deschampsia antarctica Desv. (Gramineae). Revista Brasileira de Botânica 18, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR. 2008. Does growth temperature affect the temperature responses of photosynthesis and internal conductance to CO2? A test with Eucalyptus regnans. Tree Physiology 28, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong FS, Ruhland CT, Day TA. 1999. Photosynthetic temperature response of the Antarctic vascular plants Colobanthus quitensis and Deschampsia antarctica. Physiologia Plantarum 106, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi K, Hanba YT, Terashima I. 2006. Effects of internal conductance on the temperature dependence of the photosynthetic rate in spinach leaves from contrasting growth temperatures. Plant and Cell Physiology 47, 1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi K, Hikosaka K, Terashima I. 2009. Cold-tolerant crop species have greater temperature homeostasis of leaf respiration and photosynthesis than cold-sensitive species. Plant and Cell Physiology 50, 203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Noguchi KO, Terashima I. 2005. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis in spinach leaves: analyses of photosynthetic components and temperature dependencies of photosynthetic partial reactions. Plant, Cell and Environment 28, 536–547. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota A, Canvin DT. 1985. Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase content determined with [14C]carboxypentitol bisphosphate in plants and algae. Plant Physiology 77, 735–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JN, Rickaby RE, Kapralov MV, Filatov DA. 2012. Adaptive signals in algal Rubisco reveal a history of ancient atmospheric carbon dioxide. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 367, 483–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.