Mutation of MURUS1 suppresses the highly serrated leaf phenotype that results from overexpression of CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 2 in Arabidopsis, revealing that GDP-L-fucose is involved in defining tissue boundaries during plant development.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, boundaries, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON 2, development, GDP-L-fucose, leaf

Abstract

The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC) transcription factors control plant boundary formation, thus allowing the emergence of novel growth axes. While the developmental roles of the CUC genes in different organs and across species are well characterized, upstream and downstream events that contribute to their function are still poorly understood. To identify new players in this network, we performed a suppressor screen of CUC2g-m4, a line overexpressing CUC2 that has highly serrated leaves. We identified a mutation that simplifies leaf shape and affects MURUS1 (MUR1), which is responsible for GDP-L-fucose production. Using detailed morphometric analysis, we show that GDP-L-fucose has an essential role in leaf shape acquisition by sustaining differential growth at the leaf margins. Accordingly, reduced CUC2 expression levels are observed in mur1 leaves. Furthermore, genetic analyses reveal a conserved role for GDP-L-fucose in different developmental contexts where it contributes to organ separation in the same pathway as CUC2. Taken together, our results reveal that GDP-L-fucose is necessary for proper establishment of boundary domains in various developmental contexts.

Introduction

In multicellular organisms, the development of distinct organs often requires the establishment of boundaries to individualize functional units. While physically separating organs, boundaries also act as organizing centers to control cell fate in neighboring tissues. Thus, formation and maintenance of boundaries is crucial to guide the establishment of reproducible developmental patterns (Dahmann et al., 2011).

Several transcriptional regulators are involved in the development of boundaries in plants, including the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC) transcription factors (reviewed in Žádníková and Simon, 2014; Hepworth and Pautot, 2015; Maugarny et al., 2015). They belong to the NAC (NO APICAL MERISTEM/ATAF1-2/CUC2) family, an evolutionarily conserved family of plant transcription factors notably involved in developmental processes and stress responses (Nuruzzaman et al., 2013). As players involved in boundary definition, CUC transcription factors are major regulators of plant architecture, controlling both shoot meristem maintenance (Aida et al., 1999) and correct organ separation in various developmental contexts (Aida et al., 1997; Burian et al., 2015; Gonçalves et al., 2015). In addition, CUC genes are master regulators of leaf shape through their roles in leaf margin development (Hasson et al., 2011; Nikovics et al., 2006). Detailed analysis of leaf morphogenesis has revealed the complex morphological effects of CUC activity: they repress growth locally while promoting growth in adjacent regions through a non-cell-autonomous mechanism involving auxin (Bilsborough et al., 2011; Biot et al., 2016; Blein et al., 2008; Kawamura et al., 2010; Nikovics et al., 2006). How this is mediated at the molecular level is still unclear, although some targets of the CUC transcription factors have been identified (Takeda et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2014).

In line with their complex roles, the specific expression patterns of CUC genes must be both spatially and quantitatively regulated. Their role in leaf dissection, for example, is tightly linked to expression levels: cuc2 loss-of-function mutants show smooth leaf margins, while strongly serrated leaves are observed in CUC2g-m4 plants that have increased CUC2 expression levels resulting from defective regulation of CUC2 by the microRNA miR164 (Hasson et al., 2011; Nikovics et al., 2006). More recently, hormonal pathways involving auxin and brassinosteroids have been identified as upstream regulators of CUC genes (Bilsborough et al., 2011; Gendron et al., 2012). In addition, several regulators, including the SWI/SNF chromatin remodelers BRAHMA and SPLAYED and the Polycomb-regulated transcriptional repressor DPA4, control the expression of CUC genes (Engelhorn et al., 2012; Kwon et al., 2006).

In order to gain further insights into the biological processes shaping plant boundaries, we designed a genetic screen to identify new components of CUC2-dependent developmental pathways. Using genetic approaches coupled with detailed morphometric analyses, we show that MURUS1 (MUR1), which encodes a GDP-D-mannose 4,6-dehydratase involved in GDP-L-fucose production, is required for leaf shape development and more generally for boundary definition in plants.

Methods

Plant material

The mur1-1 and mur1-2 mutant lines originated from an ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) screen performed in the Columbia (Col-0) genetic background and are described in Reiter et al. (1997). The T-DNA insertion mutant lines cuc2-3 and cuc3-105 in the Col-0 genetic background were reported by Hibara et al. (2006). The CUC2g-m4 line was first described by Nikovics et al. (2006). For the genetic screen, we used a double homozygous CUC2g-m4 line containing the pCUC2::GUS reporter, also described by Nikovics et al. (2006).

The reporter line pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS in the cuc2-3 mutant background is described in Gonçalves et al. (2015). The pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS cuc2-3 line was crossed into the mur1-1 mutant and plants were taken to generation F3 to produce a line homozygous for the pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS reporter in a double cuc2-3 mur1-1 homozygous mutant background.

A pCUC2::RFP reporter line was generated as follows: the N-terminal endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-targeting sequence of the pumpkin 2S albumin and the C-terminal ER retention signal HDEL (Matsushima et al., 2002; Zhong et al., 2008) were added by multiple rounds of PCR to the mRFP (monomeric red fluorescent protein) from pH7WGR2 (Karimi et al., 2007). After cloning into pGEM-T (Promega), the resulting ermRFP was cloned as a NotI fragment behind the 3.7 kb CUC2 promoter from the pGreen0129-t35S-ProCUC2 binary vector (Hasson et al., 2011). The resulting construct was transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 and wild-type Col-0 Arabidopsis plants were transformed by floral dipping. Primary transformants were selected in vitro for their resistance to hygromycin. The expression pattern of the pCUC2::RFP reporter was checked in the inflorescence meristem and leaves in multiple independent lines, and one line was selected for further analysis based on the quality of the fluorescence (level, pattern, and consistency between siblings) and a segregation indicating the integration of the transgene at a single locus. The pCUC2::RFP reporter was introduced into the mur1-2 mutant background by crossing and plants were taken to generation F3 to generate a line homozygous for the pCUC2::RFP reporter in an mur1-2 homozygous mutant background.

To generate the pMUR1::GUS reporter, we amplified a 2411 bp fragment upstream of the MUR1 coding sequence start site using the primers 5ʹ-AAGCTTCCCACTAGAAAAGTGACACAGT-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CCATGGTTGGGTTTTCGGATCTGGGA-3ʹ to introduce HindIII and NcoI restriction sites. The PCR product was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega). The promoter fragment was cloned into the pCAMBIA3301 binary vector using the HindIII/NcoI restriction site. The resulting construct was sequence verified and transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101, and Col-0 plants were transformed by floral dipping. Transformant plants were selected on kanamycin.

Growth conditions

M2 and M3 plants in the genetic screen were grown in a greenhouse under long-day conditions (16 h light at 23 °C and 8 h dark at 15 °C). Plants used in leaf development and morphological studies were grown in controlled-environment rooms in either short-day [1 h dawn (19 °C, 80 µmol m–2 s–1 light), 6 h day (21 °C, 120 µmol m–2 s–1 light), 1 h dusk (20 °C, 80 µmol m–2 s–1 light), 16 h dark (18 °C, no light)] or long-day [1 h dawn (19 °C, 80 µmol m–2 s–1 light), 14 h light (21 °C, 120 µmol m–2 s–1 light), 1 h dusk (20 °C, 80 µmol m–2 s–1 light) and 8 h dark (18 °C, no light)] conditions. For in vitro assays, plants were grown axenically in Arabidopsis growth medium (modified from Estelle and Somerville, 1987) containing 5 mM KNO3, 2.5 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 2 mM Ca(NO3)2, 70 µM H3BO3, 14 µM MnCl2, 0.5 µM CuSO4, 1 µM ZnSO4, 0.2 µM NaMoO4, 10 µM NaCl, 0.01 µM CoCl2, 0.005% (w/v) ammoniacal iron (III) citrate, 3.5 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 1% (w/v) saccharose, 1 mg l–1 calcium panthotenate, 0.01 mg l–1 biotin, 1 mg l–1 niacin, 1 mg l–1 pyridoxine, 1 mg l–1 thiamine, 100 mg l–1 inositol, 8 mg l–1 bromocresol purple, and 6 g l–1 agar, pH5.6. Plants were grown in a growth chamber under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) at 21 °C. For the L-fucose treatment, L-fucose (F2252, Sigma) was added to the medium at a final concentration of 10 mM and plants were grown in the same day length conditions.

All other phenotyping experiments were performed on plants grown in a greenhouse under long-day conditions (16 h light at 23 °C and 8 h dark at 15 °C).

Mutagenesis, genetic suppressor screen, and sequencing

We performed EMS mutagenesis on a CUC2g-m4 line. Seeds were mutagenized by agitation with 0.3% EMS for 17 hours, neutralized with 5 ml of 1 M sodium thiosulfate for 5 min, and washed in distilled water. Approximately 6000 mutagenized seeds were sown on soil and M2 seeds were harvested in bulks of 25 plants. Approximately 300 M2 plants per bulk were sown and screened for suppression of the leaf lobbing phenotype by visual inspection. An F2 mapping population was generated by backcrossing folivora to the parental CUC2g-m4 line. Genomic DNA was isolated from ~125 folivora mutants segregating within the F2 and pool sequenced using Illumina technology by the Earlham Institute (formerly The Genome Analysis Centre, Norwich, UK). Sequencing data were analyzed using the SHORE and SHOREmap pipelines for identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms with high frequency within the sequenced folivora population (Schneeberger et al., 2009).

Xyloglucan structural analysis

Xyloglucan analysis was based on the rapid phenotyping method using enzymatic oligosaccharide fingerprinting previously described (Lerouxel et al., 2002; Sechet et al., 2016). Mature rosette leaves were harvested and cleared in ethanol overnight at room temperature. After removal of ethanol and rehydration in water, xyloglucan oligosaccharides were generated by digesting the samples with endoglucanase in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5, in a final volume of 20 µl, overnight at 37 °C. An aliquot of 0.5 µl of the supernatant was dried on a matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass (MALDI-TOF) target, followed by the addition of 0.5 µl of super-DHB (9:1 mixture of 2,5-dihydroxy-benzoic acid and 2-hydroxy-5-methoxy-benzoic acid, Sigma-Aldrich) matrix, and dried under a fume hood prior to spectra acquisition. The MALDI-TOF mass spectra of the xyloglucan oligosaccharides were acquired with a MALDI/TOF Bruker Reflex III.

Leaf development and morphological studies

Sample preparation and scanning

Leaf silhouettes were prepared by sticking detached leaves on to a sheet of paper and scanning them using a Perfection V500 Photo scanner (Epson). For the developmental series, L6 leaves were dissected from the meristem under a stereomicroscope, mounted in water between a slide and coverslip, and imaged using an Axio Zoom.V16 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Jena, Germany; http://www.zeiss.com/). For leaf shape analysis of in vitro grown plants, L5 leaves were collected, mounted in water between a slide and coverslip, and imaged using a stereomicroscope (SMZ 1000, Nikon) coupled to a camera (ProgResC10plus, Jenoptik).

MorphoLeaf

Leaf silhouettes and measurements were obtained using MorphoLeaf software, which segments leaves and extracts relevant biological features (Biot et al., 2016). Output data analysis, statistics, and plots, both here and in subsequent experiments, were performed using R software (R Core Team, 2016) and the graphics package ggplot2.

Dissection index calculation

The leaf dissection index (DI) shape quantification method is inspired by work reported in Sicard et al. (2014). DI was calculated as leaf_DI=(leaf_perimeter2)/(4π*leaf_area) for each individual leaf. To take into account overall leaf shape, the same calculation was performed for the alpha-hull of each leaf, which is a generalization of the convex hull around the leaf serrations and petiole. Alpha-hull perimeter and area were obtained using the R package alphahull (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=alphahull). The alpha-hull DI was calculated using the formula ahull_DI=(ahull_perimeter2)/(4π*ahull_area). The final DI value, which was compared between genotypes, was calculated as the ratio between leaf_DI and ahull_DI and represents an integrative value to quantify leaf shape. The R script for the calculation of DI is available on request.

Expression data and quantification

Laser assisted microdissection and RNA extraction

Leaf margins were microdissected with the ZEISS PALM MicroBeam using the Fluar 5x/0.25 M27 objective. Leaves under 1 mm long were hand-dissected and placed on MMI membrane slides, and microdissected samples were collected in ZEISS AdhesiveCaps. Cutting parameters were adjusted throughout the experiment. Approximately 20 microdissected leaf margins were collected in each sample. RNA was extracted from samples using the Arcturus PicoPure RNA Isolation Kit, following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was controlled using the Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit.

Quantitative PCR analysis

Quantitative PCR analyses were performed on a Bio-Rad CFX connect machine using the SsoAdvance Universal SYBR Green Supermix following the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 10s, 63 °C for 10s, and 72 °C for 10s. Primers used for real-time PCR analysis are described in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online.

Imaging

The pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS reporter line was imaged with a Leica SP5 inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany; http://www.leica-microsystems.com/). Samples were excited using a 514 nm laser and fluorescence was collected with a hybrid detector at between 530 and 580 nm. The pCUC2::RFP reporter line was imaged using an Axio Zoom.V16 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy), using a custom-made filter block (excitation band pass filter 560/25, beam splitter 585, emission band pass filter 615/24, AHF, Tübingen, Germany; https://www.ahf.de/).

Image analysis

pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS signal quantification was performed manually using ImageJ. For each leaf, fluorescence was quantified in the distal sinuses of the first pair of teeth. The CUC2-VENUS levels shown in the Results are the mean intensity of the 12 most intense nuclei in each sinus, with intensity being measured on the medial plane of each nucleus.

To identify the sinus region showing pCUC2::RFP expression and quantify the fluorescence signal, we developed a dedicated macro (Qpixies) on ImageJ. This macro allows the semi-automatic identification of a zone where fluorescence signal levels are above the local background levels. By automatically defining a local background centered around the zone to quantify, this macro minimizes the variability of the quantification that may result from user definition bias. Further details of the Qpixies ImageJ macro are provided in Supplementary Protocol S1.

Results and discussion

CUC2g-m4 suppressor screen

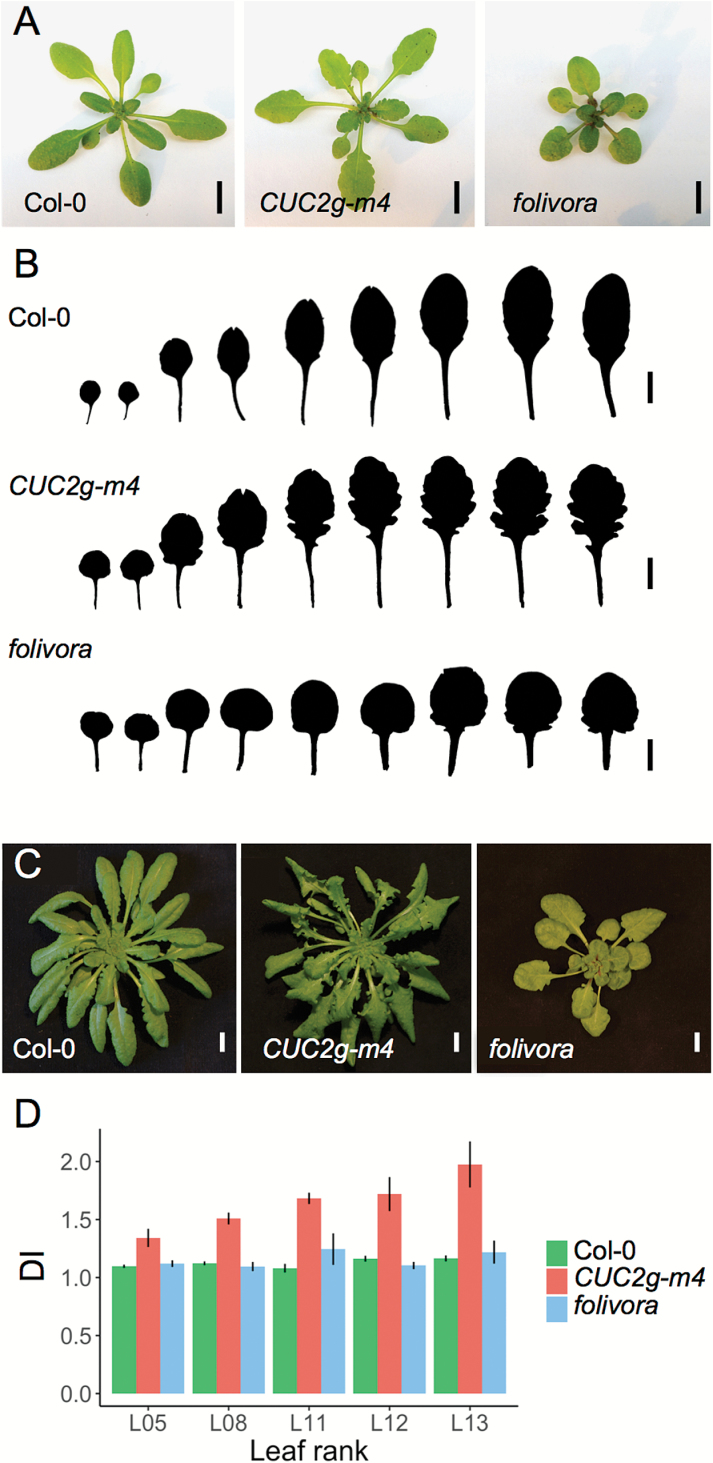

To identify new regulators involved in CUC2-dependent boundary establishment pathways, we performed a genetic suppressor screen of the CUC2g-m4 strongly dissected leaves (Fig. 1A, B) (Nikovics et al., 2006). Among the M2 plants obtained after EMS mutagenesis, we isolated a mutant with short stature, rounded leaves, and reduced leaf serrations compared with the original CUC2g-m4 line grown under long-day conditions (Fig. 1A, B). We named this mutant folivora, the Latin name for sloth, a mammal from the polyphyletic Edentata order (edentata meaning ‘toothless’). To test whether the folivora leaf phenotype depends on the growth conditions, we quantified the dissection level of leaves L5, L8, L11, L12, and L13 from wild type (Col-0), CUC2g-m4, and folivora plants grown in short-day conditions, using the DI as a shape descriptor. For all leaves analyzed, the DI in the folivora mutant was lower than that in the CUC2g-m4 line and similar to that observed in the wild type (Fig. 1C, D). This finding indicates that EMS-induced mutation(s) in folivora can suppress the increase in leaf dissection associated with the CUC2g-m4 transgene, regardless of the day length, highlighting the robustness of the folivora leaf phenotype.

Fig. 1.

Leaf phenotypes of CUC2g-m4 and the suppressor folivora. (A) Rosettes of 3-week-old Col-0, CUC2g-m4, and folivora plants grown in long-day conditions. (B) Leaf silhouettes of L1–L9 leaves of 4-week-old Col-0, CUC2g-m4, and folivora plants grown in long-day conditions. (C) Rosettes of 8-week-old Col-0, CUC2g-m4, and folivora plants grown in short-day conditions. (D) Mean dissection index (DI) of L5, L8, L11, L12, and L13 leaves of 8-week-day-old Col-0 (n=4 for each rank), CUC2g-m4 (L5, n=5; L8, n=5; L11, n=4; L12, n=6; L13, n=5), and folivora (n=6 for each leaf rank) plants grown in short-day conditions. Error bars represent SD. Scale bars=1 cm.

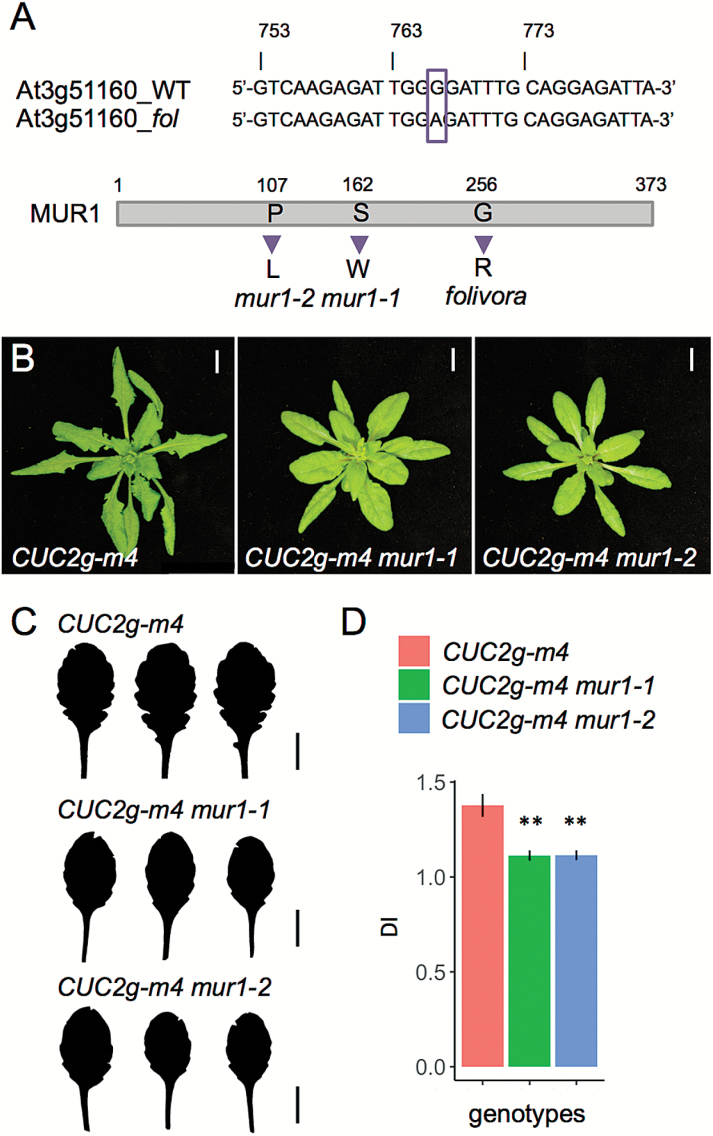

A mutation in MUR1 is responsible for CUC2g-m4 leaf phenotype suppression in folivora

To identify the causal mutation that suppresses the CUC2g-m4 leaf phenotype in folivora, we performed backcross bulk segregant analysis using the SHORE and SHOREmap pipeline (Schneeberger et al., 2009). We found an EMS-induced G-to-A mutation in the coding sequence of the locus At3g51160 leading to a G-to-R substitution at position 256 of the MURUS1 (MUR1) protein (Fig. 2A). MUR1 is a GDP-D-mannose 4,6-dehydratase involved in GDP-L-fucose production (Bonin et al., 1997). GDP-L-fucose is the activated form of L-fucose that is incorporated into cell wall glycoconjugates such as xyloglucans, rhamnogalacturonan II, and arabinogalactans (O’Neill et al., 2001; Rayon et al., 1999; Van Hengel and Roberts, 2002), and is involved in post-translational protein glycosylation (Strasser, 2016). MUR1 is expressed in young leaves and in most aerial parts of the plant, with some cell type specificity (Bonin et al., 2003; Supplementary Fig. S1). Expression data as well as analysis of loss-of-function mutants revealed that MUR1 is the major gene responsible for de novo production of GDP-L-fucose (Reiter et al., 1993; Bonin et al., 2003).

Fig. 2.

Mutations in MUR1 suppress the CUC2g-m4 leaf phenotype. (A) Partial genomic sequence of MUR1 locus in the wild-type (Col-0) and the folivora mutant showing the G-to-A EMS-induced mutation (indicated by the box), and the predicted MUR1 amino acid sequence in the mur1-1, mur1-2, and folivora mutants. (B) Rosettes of 4-week-old CUC2g-m4, CUC2g-m4 mur1-1, and CUC2g-m4 mur1-2 plants grown in long-day conditions. (C) Leaf silhouettes of three representative L6 leaves from 25-day-old CUC2g-m4, CUC2g-m4 mur1-1, and CUC2g-m4 mur1-2 plants grown in long-day conditions. (D) Mean dissection index (DI) of L6 leaves from 25-day-old CUC2g-m4 (n=12), CUC2g-m4 mur1-1 (n=14), and CUC2g-m4 mur1-2 (n=10) plants grown in long-day conditions. Error bars represent SD. **P<0.001 (Student’s t-test). Scale bars=1 cm.

The severely GDP-L-fucose-deficient mur1-1 mutant lacks fucosylated xyloglucans, instead harboring terminal α-L-galactosyl residues (Reiter et al., 1993; Zablackis et al., 1996). To show that the identified mutation in folivora MUR1 affects its encoded protein, we performed structural analysis of xyloglucans in folivora and compared the results to those for the previously described mur1-1, the wild-type, and the CUC2g-m4 line. Structural analysis of folivora xyloglucans revealed a dramatic decrease in fucosylated xyloglucans (XXFG/XLFG) and the presence of α-L-galactosyl residues (XLLG), mimicking the xyloglucan structure of mur1-1 (Supplementary Fig. S2A). We also performed allelism tests by crossing folivora to mur1-1, which bears a mutant allele of MUR1 (Reiter et al., 1993). The resulting F1 plants from mur1-1 x folivora crosses had smaller leaves than the control F1 Col-0 x folivora, a phenotype reminiscent of the homozygous mur1-1 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S2B; Reiter et al., 1993). Together, the analysis of xyloglucan structure and our genetic analysis suggest that folivora harbors a hypomorphic allele of MUR1.

Next, to test whether the inactivation of MUR1 is the genetic basis of the reduced leaf dissection in the folivora line, we introduced mur1 mutant alleles into the CUC2g-m4 background. The leaf shape of CUC2g-m4 plants carrying either homozygous mur1-1 or mur1-2 alleles was smoother than that of CUC2g-m4, as shown by both L6 leaf silhouettes and DI quantification (Fig. 2B–D). Furthermore, F1 plants from the mur1-1 x folivora and mur1-2 x folivora crosses had smaller and smoother leaves compared with Col-0 x folivora F1 plants (Supplementary Fig. S2C). Altogether, these results show that folivora carries an inactive form of MUR1 that suppresses the increased dissection of CUC2g-m4 leaves, suggesting a role for GDP-L-fucose in CUC2-dependent leaf margin morphogenesis.

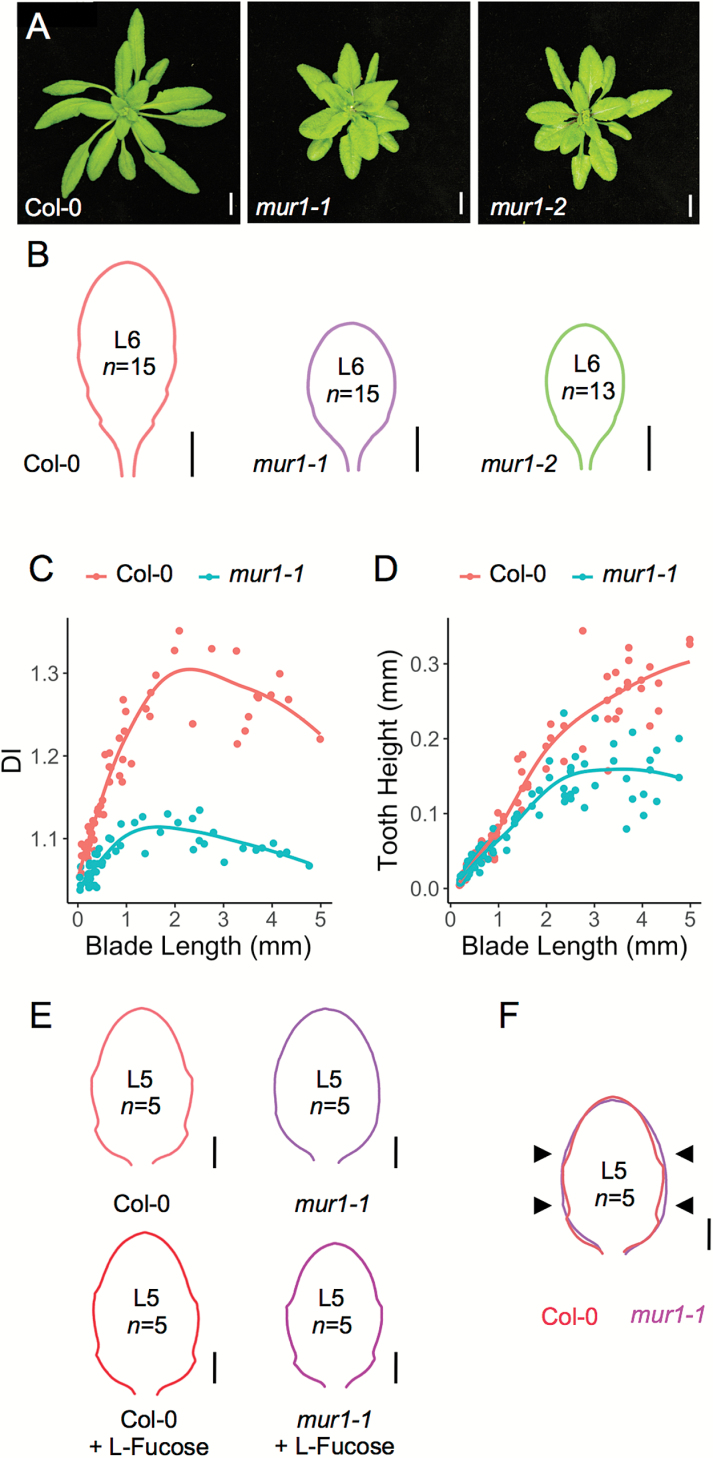

Lack of GDP-L-fucose in mur1 loss-of-function mutants leads to leaf serration defects

To dissect the role of MUR1 in leaf development, we performed a detailed morphometric analysis of mur1 loss-of-function mutants. mur1-1 and mur1-2 plants have smaller rosettes and leaves that appear smoother than wild-type leaves (Fig. 3A). The mature leaf shape of 25-day-old L6 leaves from Col-0, mur1-1, and mur1-2 was analyzed using MorphoLeaf software (Biot et al., 2016) (Fig. 3B). Mean leaf shape analysis showed that both alleles of mur1 mutants produce leaves that are smaller and less serrated than the wild type, suggesting that MUR1 is involved in leaf development.

Fig. 3.

mur1 mutants lacking GDP-L-fucose have less pronounced leaf serrations. (A) Rosettes of 4-week-old Col-0, mur1-1, and mur1-2 plants grown in long-day conditions. Scale bars=1 cm. (B) Mean silhouettes of L6 leaves from 25-day-old Col-0 (n=15), mur1-1 (n=15), and mur1-2 (n=13) plants grown in long-day conditions. Scale bars=5 mm. (C) Dissection index (DI) plotted against blade length of L6 leaves from Col-0 (red, n=61) and mur1-1 (blue, n=55) plants grown in long-day conditions. Each leaf is represented by a point, and a LOESS (local regression) curve is shown for each genotype to aid visual interpretation. (D) Tooth height of L6 first tooth plotted against blade length from Col-0 (red, n=109) and mur1-1 (blue, n=99) plants grown in long-day conditions. Each tooth is represented by a point, and a LOESS curve is shown for each genotype to aid visual interpretation. (E) Mean silhouettes of L5 leaves from 23-day-old Col-0 (n=5) and mur1-1 (n=5) plants grown in vitro in long-day conditions with and without 10 mM L-fucose supplementation. Scale bars=1 mm. (F) Superimposition of mean silhouettes of L5 leaves from Col-0 and mur1-1 shown in (E), showing altered sinus formation in the mur1-1 mutant (arrowheads). Scale bars=1 mm.

Next, we reconstructed detailed developmental trajectories of leaves using MorphoLeaf (Biot et al., 2016). Because the primordia initiation rate is comparable between mur1-1 and Col-0 (Supplementary Fig. S3A) and because L6 leaf growth rates are comparable for these two genotypes up to 5 mm length (Supplementary Fig. S3B), we chose to limit our morphometric analysis to this early stage and use leaf blade length as a proxy for leaf developmental stage. Plotting L6 DI evolution against blade length revealed that leaf primordia of mur1-1 are less dissected than the wild type, with clear shape differences appearing at an early developmental stage when leaves are <1 mm in length (Fig. 3C). To trace back the global difference in leaf shape revealed by the DI to changes in individual tooth shape, we plotted the first tooth height against blade length. This showed that mur1-1 tooth height is reduced compared with the wild type (Fig. 3D), leading to less dissected leaves. Together, these results suggest that MUR1 activity is required for the development of leaf serrations.

To further confirm the requirement of GDP-L-fucose for leaf serration development, we supplemented mur1-1 plants with exogenous L-fucose. GDP-L-fucose can be synthesized de novo via MUR1 or through a salvage pathway that converts free L-fucose via a bifunctional enzyme with L-fucokinase and GDP-L-fucose pyrophosphorylase activities (Kotake et al., 2008). Previous studies have shown that exogenous L-fucose applications can rescue mur1 growth defects and that exogenous L-fucose can be incorporated into cell walls, suggesting that the salvage pathway acts independently of MUR1 (Bonin et al., 1997; Reiter et al., 1993). In our study, mur1-1 plants grown in vitro in standard growth medium had smoother leaves than the wild type, while mur1-1 plants grown in medium supplemented with 10 mM L-fucose developed leaf serrations like the wild type (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 4); these results show that L-fucose itself is required for proper leaf serration in mur1 mutants, which are deficient in GDP-L-fucose biosynthesis. When L-fucose is provided, serrations can develop in the absence of a functional MUR1 protein, showing that MUR1 protein is not required for leaf serration. Interestingly, mur1-1 and Col-0 plants grown in vitro had comparable leaf sizes, showing that the leaf margin defect in the mutant does not result from the general growth defects seen in mur1 mutants in different growth conditions (Fig. 3E).

Leaf serrations are formed by alternating teeth and sinuses along the leaf margin. Superimposing mean leaf shapes from wild-type and mur1-1 mutant plants revealed that the mur1 leaf outline encompasses most of the wild-type leaf outline (Fig. 3F), suggesting that GDP-L-fucose deficiency affects sinus formation.

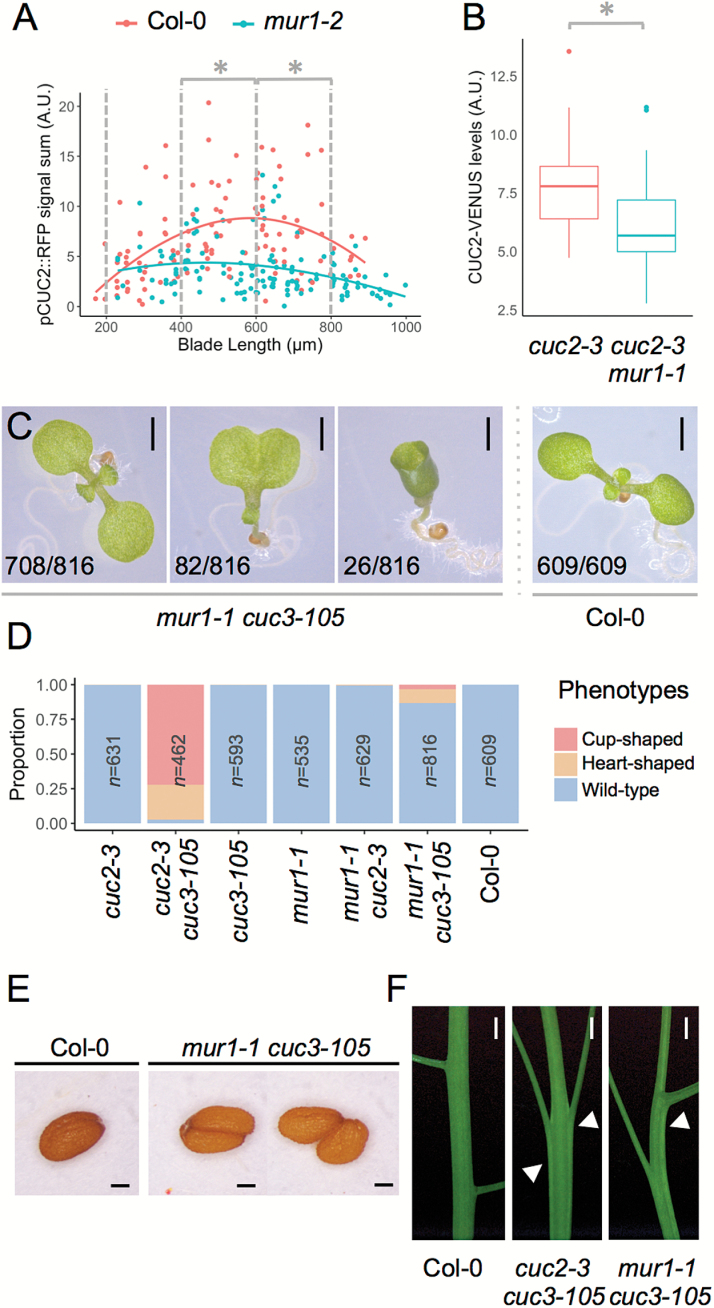

CUC2 expression is reduced in mur1 mutants

CUC2 is an important regulator of leaf serration development (Biot et al., 2016). Because GDP-L-fucose deficiency led to reduced leaf serration even in the highly serrated CUC2gm-4 line, we hypothesized that CUC2 expression is modified in the mur1 background. To test this hypothesis, we used a transgenic line reporting the transcriptional activity of the CUC2 promoter (pCUC2::RFP). We analyzed the expression of this reporter in developing leaves of both wild-type and mur1-2 mutant backgrounds by quantifying RFP fluorescence levels. CUC2 promoter activity was reduced in the sinuses at early developmental stages in mur1-2 compared with the wild type for leaves between 400 and 800 µm in length (Fig. 4A), suggesting that in the absence of GDP-L-fucose CUC2 promoter activity is impaired in developing leaves. We used laser-assisted microdissection to measure relative CUC2 mRNA accumulation in the wild-type and mur1-1 leaf margins. CUC2 mRNA levels were reduced in mur1-1 compared with the wild type (Supplementary Fig. S5), confirming the results obtained with the CUC2 transcriptional reporter.

Fig. 4.

Boundary defects in GDP-L-fucose deficient mutants. (A) Quantification of CUC2 promoter activity using a pCUC2::RFP transcriptional reporter in the wild-type and mur1-2 genetic background. Each point represents the accumulated signal intensity in the distal sinus of the first tooth of L6 leaves for Col-0 and mur1-2 plants grown in long-day conditions (see Materials and methods and Supplementary Fig. S3 for details), and a LOESS (local regression) curve is shown for each genotype to aid visual interpretation. Statistical significance was calculated on three blade length classes [200–400µm, Col-0 (n=35) and mur1-2 (n=22); 400–600 µm, Col-0 (n=30) and mur1-2 (n=38); 600–800 µm, Col-0 (n=37) and mur1-2 (n=42)]. *P<0.005 (Student’s t-test). (B) Quantification of CUC2 protein levels using the pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS translational fusion reporter in Col-0 (n=22) and mur1-1 (n=38). Leaves with blade length 250–500 µm were considered. *P<0.005 (Student’s t-test). (C) Cotyledon fusion defects in the cuc3-105 mur1-1 double mutant. From left to right: 9-day-old seedling grown in vitro with no cotyledon fusion (wild-type like); heart-shaped cotyledons; and cup-shaped cotyledons. A wild-type plant is shown in the rightmost panel. The numbers of seedlings showing each of these cotyledon phenotypes within the seedling population observed is indicated in the lower right corner of each image. Scale bars=1 mm. (D) Frequencies of cotyledon fusion defects in single and double mutants. (E) Wild-type Col-0 seed (left panel) and seed fusion defects in the cuc3-105 mur1-1 double mutant (right panel). Scale bars=100 µm. (F) Stem fusion (fasciation; arrowheads) defects in the cuc3-105 mur1-1 and cuc2-3 cuc3-105 double mutants, compared with a wild-type (Col-0) stem. Scale bars=1 mm.

Because CUC2 expression is regulated post-transcriptionally by a microRNA, miR164, we next determined whether the reduced transcriptional activity of CUC2 had an impact on CUC2 protein accumulation. For this, we measured CUC2 protein levels in mur1-1 leaves using a translational fusion reporter pCUC2::CUC2-VENUS that complements the cuc2-3 mutant allele. We quantified the CUC2-VENUS signal in distal leaf sinuses of tooth 1 and found that CUC2 protein levels are lower in the mur1-1 mutant background (Fig. 4B). Hence, CUC2 is expressed at lower levels in a GDP-L-fucose deficient mutant, in a manner consistent with the reduced sinus formation observed in the mur1-1 mutant.

GDP-L-fucose is required in CUC2-dependent boundary formation

The CUC2 transcription factor acts in a partially redundant manner with CUC3 to regulate several aspects of plant development that require boundary definition and tissue separation. Notably, CUC2 and CUC3 are required for proper separation of cotyledons, individualization of ovule primordia, and separation of the flower pedicel from the stem (Burian et al., 2015; Gonçalves et al., 2015; Hibara et al., 2006). To investigate whether GDP-L-fucose is generally required with CUC2 and/or CUC3 in such different developmental contexts, we generated the mur1-1 cuc2-3 and mur1-1 cuc3-105 double mutants and analyzed fusion phenotypes in cotyledons, stem, and seeds. cuc2-3 and cuc3-105 single mutants have low frequencies of heart-shaped cotyledon phenotypes but no cup-shaped cotyledon phenotypes (Hibara et al., 2006). While mur1-1 cuc2-3 double mutants show few to no cotyledon fusions, much like the respective single mutants, mur1-1 cuc3-105 double mutants show strong cotyledon fusions (cup- or heart-shaped cotyledons) like those observed in cuc2-3 cuc3-105 double mutants (Fig. 4C, D). Similarly, seed fusion and stem fasciation defects are observed in the mur1-1 cuc3-105 double mutant but not in the mur1-1 cuc2-3 mutant background or the single mutants (Fig. 4E, F). Because mur1-1 specifically enhances the phenotype of the cuc3-105 mutant and not that of cuc2-3, and because mur1-1 cuc3-105 double mutants phenocopy several defects of the cuc2-3 cuc3-105 double mutant, we propose that MUR1 acts in the same pathway as CUC2 to promote organ separation in different developmental contexts.

Conclusion

Collectively, our results show that GDP-L-fucose is required for the definition of organ boundaries during plant development, and that this occurs at least partially via a pathway involving CUC2. GDP-L-fucose has several roles during plant development. For instance, the dwarf phenotype of mur1-1 and mur1-2 mutants has been attributed to reduced fucose incorporation into rhamnogalacturonan II (O’Neill et al., 2001). Xyloglucan fucosylation is also impaired in the mur1, mutant which instead harbors terminal α-L-galactosyl residues (Reiter et al., 1993; Zablackis et al., 1996). Fucose can also be added to proteins in the ER by the activity of specific fucosyltransferases, which therefore have multiple roles depending on the fucosylated targets (Strasser, 2016). However, it is not known how GDP-L-fucose changes CUC2 expression levels. As GDP-L-fucose is involved in post-translational modifications of proteins, one hypothesis is that the activity of one or several upstream regulators of CUC2 expression is dependent on such modifications. Interestingly, a parallel can be drawn with Drosophila development, in which GDP-L-fucose deficiency affects cell-signaling mechanisms required for the proper expression of wingless (wg) at the dorsoventral boundary of imaginal wing discs. More precisely, O-fucosylation of the NOTCH cell-surface receptor impacts its ligand-binding capacity, thus fine-tuning NOTCH signaling and subsequent activation of wg expression (Ayukawa et al., 2012; Kopan, 2012; Okajima et al., 2005; Stanley, 2007). Another hypothesis is that CUC2 expression is indirectly impacted by changes in cell wall properties triggered by GDP-L-fucose deficiency. Finally, independently or downstream of CUC2 expression, such modifications of cell wall properties and/or post-translational modifications of proteins may also affect the differential growth that accompanies boundary function. Although further analyses will be necessary to pinpoint how GDP-L-fucose modulates plant boundary definition, here we provide evidence for a new role for GDP-L-fucose in leaf shape development and, more generally, boundary domain definition, and broaden our understanding of plant architecture development.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. MUR1 expression pattern.

Fig. S2. folivora harbors a hypomorphic allele of MUR1.

Fig. S3. Col-0 and mur1-1 leaf initiation and growth parameters.

Fig. S4. Original data showing that L-fucose treatment restores mur1-1 leaf serration phenotype in vitro.

Fig. S5. Analysis of CUC2 expression in wild type and mur1-1 leaf margins.

Table S1. List of qPCR primers used in this study.

Protocol S1. Qpixies macro for ImageJ.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

BG, PL, and NA conceived and designed the experiments. BG, AM-C, BA, AH, and NA performed the experiments with input from GM and PL. BG and EG performed xyloglucan structure analysis. NB and NA performed laser-assisted microdissection experiments. AH generated the pCUC2::RFP transgenic line. BG, MC, TB, and PL developed the Qpixies macro. BG, PL, and NA wrote the paper with input from the other authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stéphane Verger for his help with SHORE and SHOREmap pipelines; Jasmine Burguet for advice with R analysis; and Herman Höfte and Aline Voxeur for discussions. This work was supported by the Agence National de la Recherche grants LEAFNET (ANR-12-PDOC-0003) and MORPHOLEAF (ANR-10-BLAN-1614). MC was partly supported by the Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero. The IJPB benefits from the support of the Labex Saclay Plant Sciences-SPS (ANR-10-LABX-0040-SPS).

References

- Aida M, Ishida T, Fukaki H, Fujisawa H, Tasaka M. 1997. Genes involved in organ separation in Arabidopsis: an analysis of the cup-shaped cotyledon mutant. The Plant Cell 9, 841–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aida M, Ishida T, Tasaka M. 1999. Shoot apical meristem and cotyledon formation during Arabidopsis embryogenesis: interaction among the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON and SHOOT MERISTEMLESS genes. Development 126, 1563–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayukawa T, Matsumoto K, Ishikawa HO, Ishio A, Yamakawa T, Aoyama N, Suzuki T, Matsuno K. 2012. Rescue of Notch signaling in cells incapable of GDP-L-fucose synthesis by gap junction transfer of GDP-L-fucose in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 15318–15323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborough GGD, Runions A, Barkoulas M, Jenkins HW, Hasson A, Galinha C, Laufs P, Hay A, Prusinkiewicz P, Tsiantis M. 2011. Model for the regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana leaf margin development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 3424–3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biot E, Cortizo M, Burguet J et al. 2016. Multiscale quantification of morphodynamics: MorphoLeaf software for 2D shape analysis. Development 143, 3417–3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blein T, Pulido A, Vialette-Guiraud A, Nikovics K, Morin H, Hay A, Johansen IE, Tsiantis M, Laufs P. 2008. A conserved molecular framework for compound leaf development. Science 322, 1835–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin CP, Freshour G, Hahn MG, Vanzin GF, Reiter WD. 2003. The GMD1 and GMD2 genes of Arabidopsis encode isoforms of GDP-D-mannose 4,6-dehydratase with cell type-specific expression patterns. Plant Physiology 132, 883–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin CP, Potter I, Vanzin GF, Reiter WD. 1997. The MUR1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana encodes an isoform of GDP-D-mannose-4,6-dehydratase, catalyzing the first step in the de novo synthesis of GDP-L-fucose. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 94, 2085–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burian A, Raczyńska-Szajgin M, Borowska-Wykręt D, Piatek A, Aida M, Kwiatkowska D. 2015. The CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON2 and 3 genes have a post-meristematic effect on Arabidopsis thaliana phyllotaxis. Annals of Botany 115, 807–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahmann C, Oates AC, Brand M. 2011. Boundary formation and maintenance in tissue development. Nature Reviews Genetics 12, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhorn J, Reimer JJ, Leuz I, Göbel U, Huettel B, Farrona S, Turck F. 2012. Development-related PcG target in the apex 4 controls leaf margin architecture in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 139, 2566–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estelle MA, Somerville C. 1987. Auxin-resistant mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana with an altered morphology. Molecular and General Genetics 206, 200–206 [Google Scholar]

- Gendron JM, Liu JS, Fan M, Bai MY, Wenkel S, Springer PS, Barton MK, Wang ZY. 2012. Brassinosteroids regulate organ boundary formation in the shoot apical meristem of Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 21152–21157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves B, Hasson A, Belcram K et al. 2015. A conserved role for CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes during ovule development. The Plant Journal 83, 732–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson A, Plessis A, Blein T, Adroher B, Grigg S, Tsiantis M, Boudaoud A, Damerval C, Laufs P. 2011. Evolution and diverse roles of the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes in Arabidopsis leaf development. The Plant Cell 23, 54–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth SR, Pautot VA. 2015. Beyond the divide: boundaries for patterning and stem cell regulation in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 6, 1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibara K, Karim MR, Takada S, Taoka K, Furutani M, Aida M, Tasaka M. 2006. Arabidopsis CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3 regulates postembryonic shoot meristem and organ boundary formation. The Plant Cell 18, 2946–2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, Depicker A, Hilson P. 2007. Recombinational cloning with plant gateway vectors. Plant Physiology 145, 1144–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura E, Horiguchi G, Tsukaya H. 2010. Mechanisms of leaf tooth formation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 62, 429–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R. 2012. Notch signaling. Cold Spring Harbour Perspectives in Biology 4, a011213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake T, Hojo S, Tajima N, Matsuoka K, Koyama T, Tsumuraya Y. 2008. A bifunctional enzyme with L-fucokinase and GDP-L-fucose pyrophosphorylase activities salvages free L-fucose in Arabidopsis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283, 8125–8135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon CS, Hibara K, Pfluger J, Bezhani S, Metha H, Aida M, Tasaka M, Wagner D. 2006. A role for chromatin remodeling in regulation of CUC gene expression in the Arabidopsis cotyledon boundary. Development 133, 3223–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerouxel O, Choo TS, Séveno M, Usadel B, Faye L, Lerouge P, Pauly M. 2002. Rapid structural phenotyping of plant cell wall mutants by enzymatic oligosaccharide fingerprinting. Plant Physiology 130, 1754–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima R, Hayashi Y, Kondo M, Shimada T, Nishimura M, Hara-Nishimura I. 2002. An endoplasmic reticulum-derived structure that is induced under stress conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 130, 1807–1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugarny A, Gonçalves B, Arnaud N, Laufs P. 2015. CUC transcription factors: to the meristem and beyond. In: Plant transcription factors: evolutionary, structural and functional aspects. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Nikovics K, Blein T, Peaucelle A, Ishida T, Morin H, Aida M, Laufs P. 2006. The balance between the MIR164A and CUC2 genes controls leaf margin serration in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 18, 2929–2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuruzzaman M, Sharoni AM, Kikuchi S. 2013. Roles of NAC transcription factors in the regulation of biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants. Frontiers in Microbiology 4, 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill MA, Eberhard S, Albersheim P, Darvill AG. 2001. Requirement of borate cross-linking of cell wall rhamnogalacturonan II for Arabidopsis growth. Science 294, 846–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima T, Xu A, Lei L, Irvine KD. 2005. Chaperone activity of protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 promotes notch receptor folding. Science 307, 1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team 2016. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Raman S, Greb T, Peaucelle A, Blein T, Laufs P, Theres K. 2008. Interplay of miR164, CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON genes and LATERAL SUPPRESSOR controls axillary meristem formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 55, 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayon C, Cabanes-Macheteau M, Loutelier-Bourhis C, Salliot-Maire I, Lemoine J, Reiter WD, Lerouge P, Faye L. 1999. Characterization of N-glycans from Arabidopsis. Application to a fucose-deficient mutant. Plant Physiology 119, 725–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter WD, Chapple CC, Somerville CR. 1993. Altered growth and cell walls in a fucose-deficient mutant of Arabidopsis. Science 261, 1032–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter WD, Chapple C, Somerville CR. 1997. Mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana with altered cell wall polysaccharide composition. The Plant Journal 12, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger K, Ossowski S, Lanz C, Juul T, Petersen AH, Nielsen KL, Jørgensen JE, Weigel D, Andersen SU. 2009. SHOREmap: simultaneous mapping and mutation identification by deep sequencing. Nature Methods 6, 550–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechet J, Frey A, Effroy-Cuzzi D et al. 2016. Xyloglucan metabolism differentially impacts the cell wall characteristics of the endosperm and embryo during arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Physiology 170, 1367–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicard A, Thamm A, Marona C, Lee YW, Wahl V, Stinchcombe JR, Wright SI, Kappel C, Lenhard M. 2014. Repeated evolutionary changes of leaf morphology caused by mutations to a homeobox gene. Current Biology 24, 1880–1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley P. 2007. Regulation of Notch signaling by glycosylation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 17, 530–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R. 2016. Plant protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 26, 926–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Hanano K, Kariya A, Shimizu S, Zhao L, Matsui M, Tasaka M, Aida M. 2011. CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 transcription factor activates the expression of LSH4 and LSH3, two members of the ALOG gene family, in shoot organ boundary cells. The Plant Journal 66, 1066–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C, Zhang X, He J et al. 2014. An organ boundary-enriched gene regulatory network uncovers regulatory hierarchies underlying axillary meristem initiation. Molecular Systems Biology 10, 755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hengel AJ, Roberts K. 2002. Fucosylated arabinogalactan-proteins are required for full root cell elongation in arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 32, 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablackis E, York WS, Pauly M, Hantus S, Reiter WD, Chapple CC, Albersheim P, Darvill A. 1996. Substitution of L-fucose by L-galactose in cell walls of Arabidopsis mur1. Science 272, 1808–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Žádníková P, Simon R. 2014. How boundaries control plant development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 17, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Lin Z, Grierson D. 2008. Tomato ethylene receptor-CTR interactions: visualization of NEVER-RIPE interactions with multiple CTRs at the endoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.