SUMMARY

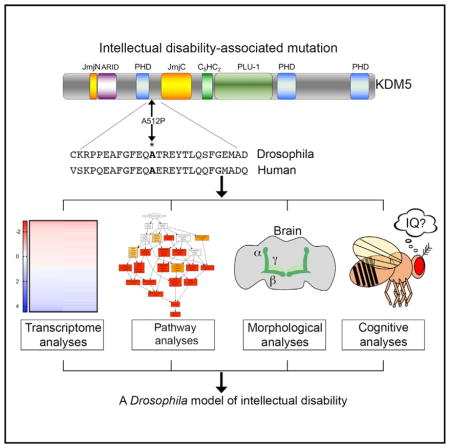

Mutations in KDM5 family histone demethylases cause intellectual disability in humans. However, the molecular mechanisms linking KDM5-regulated transcription and cognition remain unknown. Here, we establish Drosophila as a model to understand this connection by generating a fly strain harboring an allele analogous to a disease-causing missense mutation in human KDM5C (kdm5A512P). Transcriptome analysis of kdm5A512P flies revealed a striking downregulation of genes required for ribosomal assembly and function and a concomitant reduction in translation. kdm5A512P flies also showed impaired learning and/or memory. Significantly, the behavioral and transcriptional changes in kdm5A512P flies were similar to those specifically lacking demethylase activity. These data suggest that the primary defect of the KDM5A512P mutation is a loss of histone demethylase activity and reveal an unexpected role for this enzymatic function in gene activation. Because translation is critical for neuronal function, we propose that this defect contributes to the cognitive defects of kdm5A512P flies.

In Brief

In humans, mutations in the transcriptional regulator KDM5 result in intellectual disability (ID). Here, Zamurrad et al. generate a Drosophila strain harboring a KDM5 mutation equivalent to an ID-associated allele to reveal a conserved role for KDM5 in cognition and an unexpected role for KDM5′s enzymatic activity in gene activation.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with intellectual disability (ID) show an impaired ability to reason, learn, and solve problems and are defined by a score of less than 70 in an IQ test. Mutations in over 400 genes have been implicated in ID, although the underlying molecular links between genotype and phenotype for most of these genes remain unknown (Oortveld et al., 2013). Proteins that bind, remodel, or modify chromatin play key roles during development, and their dysfunction is linked to many diseases, including neurodevelopmental disorders like ID (Johansson et al., 2014). We focus here on one chromatin modifier, KDM5, that is essential for cognition in mammals and acts by binding to, and enzymatically altering, the tail region of histone H3. Mammals encode four KDM5 paralogs, KDM5A, KDM5B, KDM5C, and KDM5D, while organisms with smaller genomes such as Drosophila and C. elegans encode a single KDM5 protein. KDM5 family proteins share a similar domain structure that allows them to influence gene expression through several distinct mechanisms. The Jumonji C (JmjC) domain is the enzymatic core of KDM5 proteins, and its only known role is to demethylate histone H3 that is trimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me3) (Klose and Zhang, 2007). In addition to removing H3K4me3, KDM5 proteins have two other domains that recognize the methylation status of H3K4. The C-terminal PHD motif binds to H3K4me2/3 and the N-terminal PHD recognizes histone H3 that is unmethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me0) (Li et al., 2010; Torres et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2009). In addition to chromatin-based activities, KDM5 can also bind DNA in vitro through its A/T-rich interaction domain (ARID) (Tu et al., 2008; Yao et al., 2010).

In all organisms examined, KDM5 proteins bind predominantly to promoter regions surrounding the transcriptional start site (TSS) (Iwase et al., 2016; Liu and Secombe, 2015; Lopez-Bigas et al., 2008; Xie et al., 2011). One means by which KDM5 proteins find their target genes is through interactions with sequence-specific transcription factors, including E2F, Myc, Foxo, and the Su(H) complex that acts downstream of Notch signaling (Liefke et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014; Secombe et al., 2007; van Oevelen et al., 2008). Once at a promoter, KDM5 can affect transcription by demethylating promoter H3K4me3, which is a hallmark of transcriptionally active genes (Johansson et al., 2014). This activity is therefore primarily thought of as repressing target gene expression, a prediction that holds true for some KDM5 targets (Christensen et al., 2007). KDM5 proteins can also repress or activate transcription by demethylase-independent mechanisms. For example, KDM5 proteins can interact with the NuRD chromatin remodeling and sin3A/HDAC histone deacetylase complexes that impact transcription by altering nucleosome positioning and histone acetylation mechanisms, respectively (Barrett et al., 2007; Gajan et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2007, 2009; Nishibuchi et al., 2014).

In humans, mutations in KDM5A, KDM5B, and KDM5C are found in patients with ID, implicating KDM5-regulated transcription in the development or activity of neuronal tissues (Vallianatos and Iwase, 2015). KDM5D is Y-linked, and its role in cognition remains uncharacterized. Mutations in KDM5C are the most well studied and are predicted to account for 0.7%–3% of males with X-linked ID (XLID) (Gonçalves et al., 2014; Ropers and Hamel, 2005). To date, 31 mutations in KDM5C have been observed segregating in families with non-syndromic or syndromic ID (Gonçalves et al., 2014; Grafodatskaya et al., 2013; Vallianatos and Iwase, 2015). One mutation in KDM5A has been identified in a family study of autosomal recessive non-syndromic ID (Najmabadi et al., 2011). Notably, this missense mutation affects an arginine that is also found altered in KDM5C in XLID patients, providing additional support for a causal link between this mutation and cognitive defects (Tzschach et al., 2006). Genome-wide correlative studies have also identified nine missense, nonsense, and frameshift mutations in KDM5B in autism patients who display ID (De Rubeis et al., 2014; Iossifov et al., 2014). While nonsense and frameshift mutations are expected to result in a loss of KDM5 proteins, missense mutations are more likely to alter the transcription of a clinically relevant subset of target genes. Emphasizing the importance of residues affected by missense alleles, all disease-associated mutations in KDM5A, KDM5B, and KDM5C characterized to date occur in amino acids that are evolutionarily conserved between humans and Drosophila.

Current models propose that disrupting the enzymatic activity of KDM5 proteins leads to cognitive impairment in human patients (Vallianatos and Iwase, 2015). Consistent with this, eight of nine missense mutations in KDM5C examined show significantly reduced in vitro histone demethylase activity (Brookes et al., 2015; Iwase et al., 2007; Rujirabanjerd et al., 2010; Tahiliani et al., 2007). However, these effects were modest (≤2-fold), and no mutant proteins have been examined for demethylase activity defects in an in vivo context. This point is particularly salient in light of the fact that missense mutations in KDM5 proteins do not cluster in the catalytic JmjC domain and are instead spread throughout the protein (Vallianatos and Iwase, 2015). Whether the enzymatic activity of KDM5 proteins is a critical contributor to neuronal function therefore remains unknown.

Direct genotype-phenotype investigations in human patients have been confounded by the variability in clinical presentation of patients with a mutation in KDM5C. Mutations predicted to be genetic null alleles cause mild to severe ID and can be non-syndromic or syndromic with other features such as short stature, seizures, and aggression (Gonçalves et al., 2014; Tzschach et al., 2006). Diverse genetic backgrounds may contribute to this variability. In addition, clinical severity may be influenced by the efficiency of compensation by other KDM5 family proteins since KDM5B expression was upregulated in lymphoblastoid cells from a patient with a frameshift KDM5C mutation (Jensen et al., 2010).

The molecular links between KDM5 family proteins and neuronal (dys)function remain unclear, underscoring the need for a genetically amenable model. A major step forward in this goal came from the generation of a KDM5C knockout mouse strain designed to model the effects of nonsense and other mutations expected to result in a complete loss of KDM5C gene function (Iwase et al., 2016; Scandaglia et al., 2017). KDM5C knockout mice had defective learning, aberrant social interactions, hyperreflexia, and propensity for seizures. Despite recapitulating many of the clinical features of patients with mutations in KDM5C, genome-wide transcriptome analyses of frontal cortex and amygdala neurons in KDM5C knockout mice did not reveal any clear pathways linked to ID (Iwase et al., 2016). An additional animal model could therefore provide insight into the genes and pathways that are dysregulated by ID-associated mutations in KDM5 family proteins.

Drosophila is a well-established model to investigate the molecular and cellular defects underlying human neurodevelopmental disorders (Oortveld et al., 2013; van der Voet et al., 2014). Here, we establish Drosophila as a model for understanding the mechanisms linking mutations in KDM5 family proteins and cognitive defects. Specifically, we generated a fly strain harboring a missense allele of kdm5 analogous to a mutation in KDM5C found in ID patients that does not alter protein levels (kdm5A512P). We show that kdm5A512P mutant flies have learning and/or memory deficits and define the gene expression defects associated with this allele. These analyses revealed a striking dysregulation of genes involved in cytoplasmic translation that we propose to be a key cause of the cognitive phenotypes associated with this mutation.

RESULTS

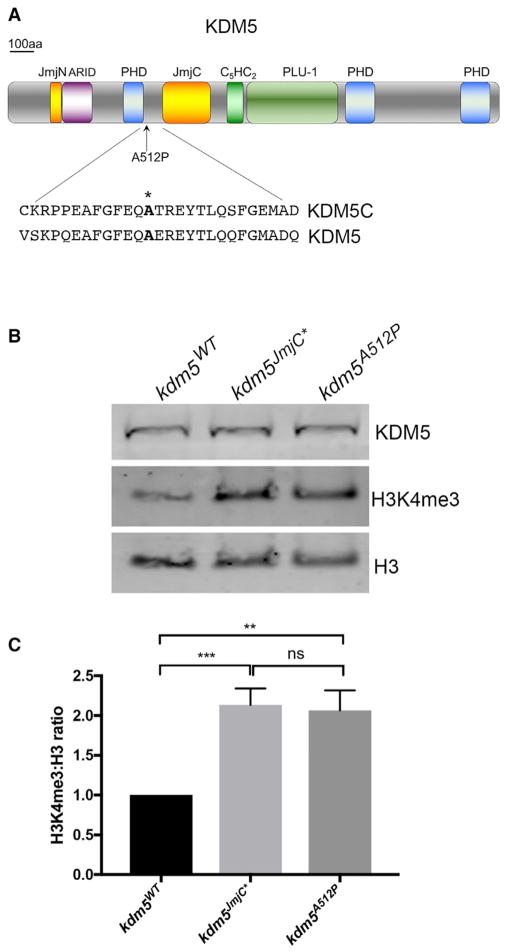

The ID-Associated Allele kdm5A512P Disrupts Transcription

Mutations in KDM5 family genes result in cognitive phenotypes in humans and mice (Vallianatos and Iwase, 2015). To establish Drosophila as a model to define the molecular defects of disease-associated alleles, we generated a mutation in fly kdm5 equivalent of the human disease-associated mutation KDM5CA388P (kdm5A512P) (Jensen et al., 2005). The kdm5A512P mutation lies between the N-terminal PHD motif that binds to histone H3 (Li et al., 2010) and the JmjC demethylase domain (Figure 1A). Because the mutation lies outside of the histone H3 binding region of the PHD motif, it is not expected to disrupt this activity. It is, however, likely to affect the adjacent JmjC domain, as KDM5CA388P decreases in vitro demethylase activity toward a histone peptide substrate by 55% (Iwase et al., 2007). The extent of its enzymatic defects in vivo is unknown. Thus, it is not clear whether the cognitive effects of this allele are caused by its attenuated enzymatic activity or whether this mutant protein has additional defects.

Figure 1. Generation of the ID-Associated Mutation kdm5A512P.

(A) Drosophila A512P mutation and homology between human KDM5C and fly KDM5.

(B) Western showing levels of KDM5, H3K4me3, and histone H3.

(C) Quantification of H3K4me3:H3 ratio. H3K4me3 levels are 1.9 ± 0.08- and 1.8 ± 0.1-fold higher, respectively (**p = 0.002; ***p = 0.0007). Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

We previously generated transgenes encoding wild-type KDM5 or a JmjC domain point mutant form of KDM5 that abolishes demethylase activity, that are expressed under the control of the kdm5 endogenous promoter (Li et al., 2010; Navarro-Costa et al., 2016). We similarly generated a transgene encoding KDM5A512P. The wild-type, demethylase inactive (kdm5JmjC*) and kdm5A512P transgenes were crossed into a kdm5140 null mutant background such that the transgene was the sole source of KDM5. kdm5JmjC* and kdm5A512P homozygous mutant flies were viable, appeared morphologically normal, and expressed KDM5 at wild-type levels (Figure 1B). To determine the enzymatic deficit of KDM5A512P, we quantified levels of H3K4me3 as an indirect measure of demethylase activity and found a 2-fold increase in this chromatin mark that was indistinguishable from the demethylase-inactive kdm5JmjC* strain (Figures 1B and 1C). This suggests that the KDM5A512P point mutation has a more severe effect on enzymatic activity in vivo than predicted based on in vitro data.

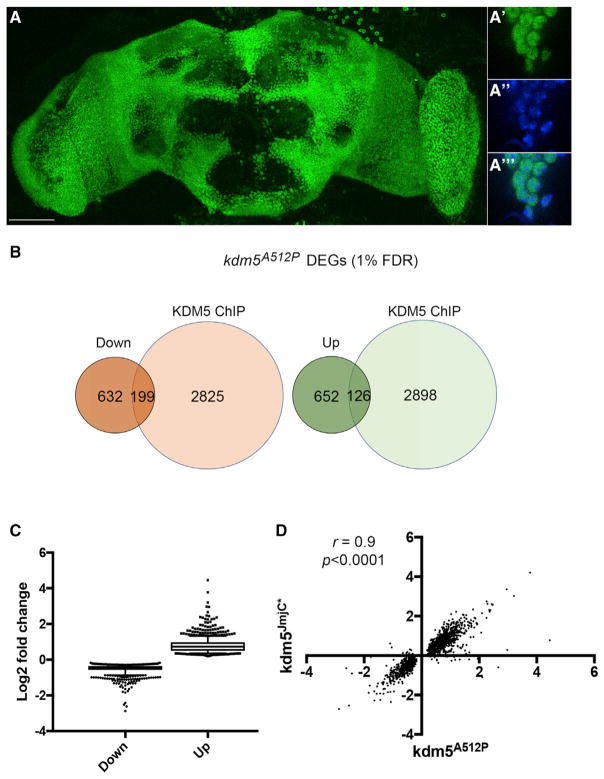

Defining how ID-associated mutations in KDM5 disrupt its ability to regulate transcription is key to understanding their link to disease. Because KDM5 is a nuclear-localized protein found uniformly throughout the adult Drosophila brain (Figure 2A), we carried out mRNA sequencing (mRNA-seq) from whole kdm5A512P mutant adult heads. Compared to kdm5WT, kdm5A512P mutants had 1,609 differentially expressed genes, 778 of which were upregulated and 831 of which were downregulated (1% false-discovery rate [FDR]; Figure 2B; Table S1). We further categorized dysregulated genes into direct and indirect targets using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data generated using adult flies (Liu and Secombe, 2015), and found that 20% of affected genes had significant KDM5 binding at their promoter region (p = 5.1e-08). KDM5A512P affects the ability of KDM5 to activate and repress transcription, since 16% of upregulated and 24% of downregulated genes are direct targets (Figure 2B; Table S1). As previously seen in Drosophila and mammalian systems, changes to gene expression of direct and indirect targets were mild (Iwase et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2014; Liu and Secombe, 2015; Lopez-Bigas et al., 2008; Lussi et al., 2016) (Figure 2C). Because KDM5A512P affects histone demethylase activity, we also carried out RNA-seq of kdm5JmjC* adult heads to determine the extent to which loss of enzymatic activity contributed to the transcriptional defects of kdm5A512P animals. Examining all 1,609 genes that were dys-regulated in kdm5A512P revealed that these changes were strikingly similar in kdm5JmjC* flies (r = 0.9; p < 0.0001; Figure 2D). The loss of enzymatic activity is therefore likely to be the primary defect of the KDM5A512P mutant protein.

Figure 2. KDM5 Is Broadly Expressed in Nuclei of the Adult Brain and Is Required for Normal Gene Expression Programs.

(A) kdm5WT adult brain of showing KDM5:HA expression using an anti-HA antibody. (A′, A′, A‴) Pars intercerebralis region showing nuclear localized KDM5:HA (A′), DAPI (A′), and a merged image (A‴). Scale bar, 50 microns.

(B) Direct and indirect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in kdm5A512P heads using a 1% FDR cutoff.

(C) Boxplot showing range of changes to gene expression.

(D) Correlation between gene expression changes in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* for all 1,609 DEGs (1% FDR).

Transcriptome Analyses of kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* Reveal the Downregulation of Genes Required for Ribosome Function

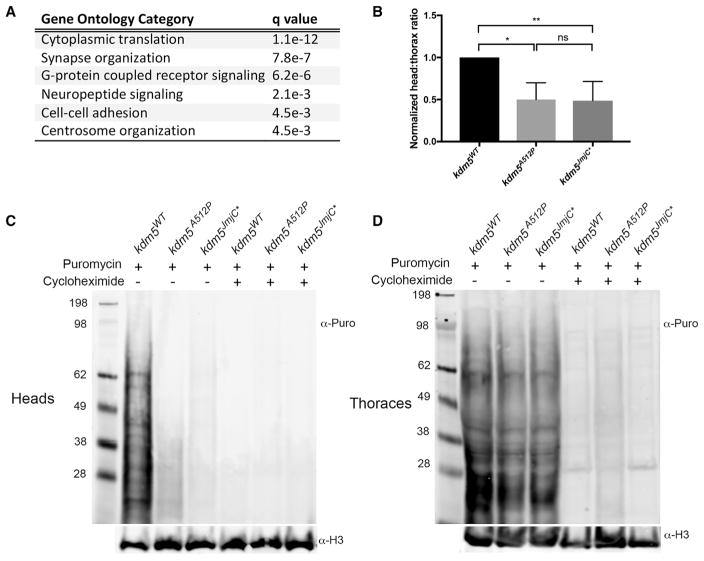

To determine whether genes dysregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* were enriched for functional categories, we utilized programs that mine gene ontology (GO) information, including GO David (Huang et al., 2009) and GOrilla (Eden et al., 2009). The most significantly enriched category of genes affected in the kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* datasets was cytoplasmic translation, a process well-established to be essential in forming long-term memories (Figure 3A) (Korte and Schmitz, 2016). All genes in this category were downregulated and 92% were direct KDM5 targets. Interestingly, this included genes involved in several aspects of translation, including 34 ribosomal protein (39% of all Rp) genes, genes involved in ribosomal RNA processing and modification (e.g., fibrillarin, Nop5, hoi-palloi), and factors necessary for translation initiation and elongation (e.g., eIF3b, eEF1gamma) (Aylett and Ban, 2017). Other GO-enriched categories were consistent with a role for KDM5 in neuronal function, including synapse function and G-protein-coupled signaling (Figure 3A). Genes in these categories did not have an associated KDM5 ChIP peak at their promoters so are likely to be indirectly affected in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutant flies. Dysregulated genes required at synapses and in cell-cell communication included genes that encode immunoglobulin domain transmembrane proteins involved in determining the specificity of synaptic connections between neurons and their target cells (Carrillo et al., 2015). Within the G-protein signaling category, notable genes included those required for the production (Tdc1, Tdc2) and reception (Oamb, Octbeta3R) of the neurotransmitter octopamine that is well-established to be necessary for appetitive olfactory short-term learning and memory (Kim et al., 2013).

Figure 3. kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* Flies Show Reduced Translation in Head Tissue.

(A) GO analyses using 1,293 DEGs that met the 1% FDR statistical cutoff for both kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC*.

(B) Quantitation of head:thorax ratio of puromycin incorporation after histone H3 normalization. *p = 0.02; **p = 0.01. n = 3. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

(C) Anti-puromycin and anti-histone H3 (loading control) western blots using adult heads. Flies were fed puromycin (lanes 1–3) or puromycin and cycloheximide (lanes 4–6). Genotypes are as indicated.

(D) Thorax tissue from head samples shown in (C).

Based on the large number of genes required for translation that were downregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* brains, and the importance of this process to cognition, we directly assessed levels of de novo translation. Consistent with our transcriptome data, heads from kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutant flies fed the aminoacyl tRNA analog puromycin showed a 2-fold reduction in nascent polypeptide synthesis (Figures 3B and 3C). Importantly, ribosome function was unaffected in thorax tissue, suggesting that reduced translation is not globally affected in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* animals (Figure 3D). Co-feeding of puromycin and the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide served as a specificity control in these assays (Figures 3C and 3D).

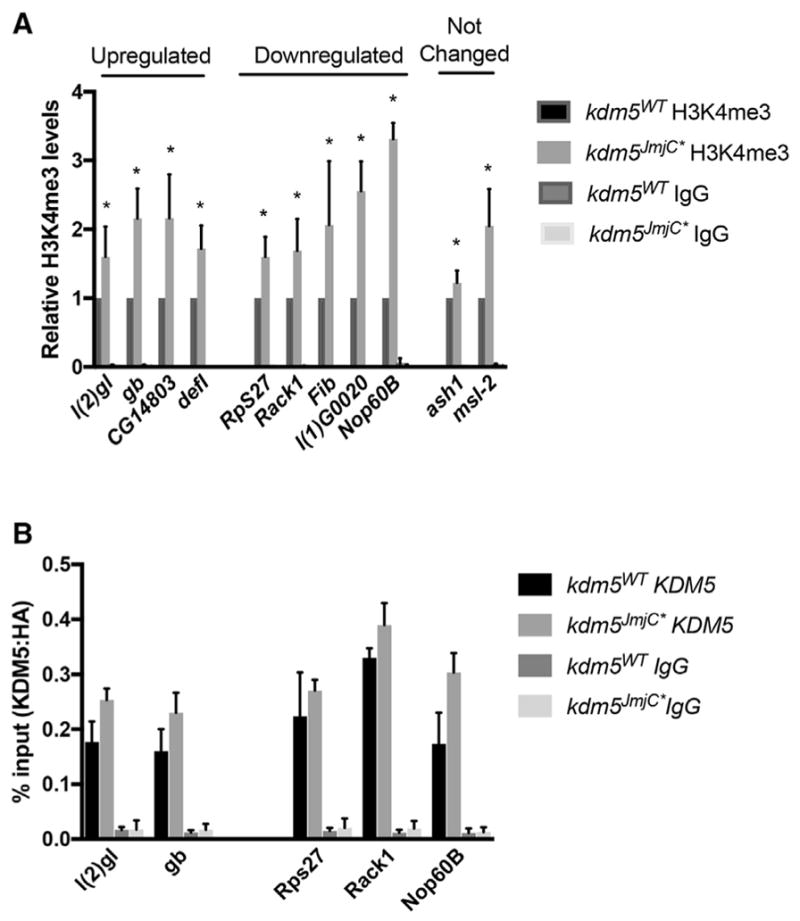

The Demethylase Activity of KDM5 Is Required for Transcriptional Activation

Because H3K4me3 is associated with the promoter region of actively transcribed genes (Greer and Shi, 2012), KDM5-mediated demethylation is traditionally thought to lead to transcriptional repression. Accordingly, 37% of the KDM5-bound genes dysregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* were upregulated. However, the remaining 63% of directly regulated genes were downregulated, implicating the demethylase activity of KDM5 in gene activation. We therefore examined levels of promoter H3K4me3 at KDM5-bound genes whose expression was upregulated (gb, l(2)gl, CG14803, defl), downregulated (RpS27, Rack1, Fib, l(1)G0020, Nop60B), or unaffected (ash1 and msl-2) in kdm5JmjC* flies. These analyses revealed that genes in all three classes showed significantly increased levels of promoter H3K4me3 (Figure 4A). Increased H3K4me3 levels therefore did not correlate with the changes to gene expression observed. To confirm that the changes to gene expression were not a consequence of the mutant KDM5JmjC* protein failing to be recruited to some or all of its target promoters, we analyzed promoter binding by ChIP. As shown in Figure 4B, KDM5WT and KDM5JmjC* are recruited equivalently to promoters of upregulated and downregulated genes.

Figure 4. Analyses of Promoter H3K4me3 Levels and KDM5 Recruitment.

(A) Anti-H3K4me3 and control IgG ChIP from kdm5WT and kdm5JmjC* flies using primers near the TSS. Shown as a ratio compared to wild type. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

(B) Anti-HA (KDM5) and control IgG ChIP from kdm5WT and kdm5JmjC* flies showing similar promoter recruitment at genes that were upregulated or downregulated in RNA-seq analyses.

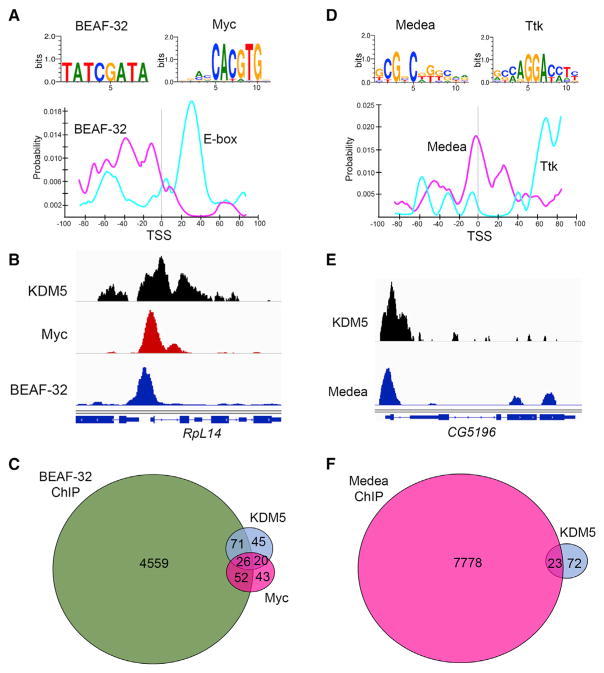

One means by which KDM5 could activate and repress transcription in a context-dependent manner is through recruitment by distinct transcription factor complexes at target promoters. However, interrogation of KDM5-bound sequences at genes that were dysregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* using MEME-ChIP did not reveal any significant enrichment for any known transcription factor binding sites (Machanick and Bailey, 2011). Likewise, the DNA binding ARID motif of KDM5 is unlikely to contribute to promoter recruitment as no significant enrichment was observed for its known in vitro binding site CCGCCC (Tu et al., 2008). We therefore explored the differences between direct KDM5 target genes that were upregulated or downregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* by analyzing their core promoter regions using CentriMo (Bailey and Machanick, 2012). The TSS ± 100 bp of downregulated genes were enriched for two sequences with known cognate binders. Binding sites for the insulator protein BEAF-32 were observed upstream of the TSS (p = 2.4e-9) (Figure 5A). We confirmed this correlation using BEAF-32 ChIP-seq data generated using cultured Drosophila S2 cells (Nègre et al., 2010) (p = 2.2e-16; Figures 5B and 5C). Slightly downstream of the TSS, E-box sequences were enriched (CACGTG; p = 2.1e-9; Figure 5A). Although the E-box motif is bound by several basic-helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors, we focused on the transcription factor Myc because it is a well-established activator of genes required for translation and cell growth (Gallant, 2013). Additionally, Myc genetically and physically interacts with KDM5 in Drosophila and mice (Li et al., 2010; Outchkourov et al., 2013; Secombe et al., 2007). We therefore compared our data to the Myc bound and regulated targets identified using S2 cells (Herter et al., 2015) and found that 28% of KDM5 downregulated genes were directly regulated by Myc (p = 2.5e-7; Figures 5B and 5C). A significant number of KDM5 targets were also bound by both Myc and BEAF-32 (p = 2.2e-16; Figure 5C).

Figure 5. KDM5-Activated Genes Are Enriched for Promoter-Proximal Myc Binding and Insulator Elements.

(A) Consensus BEAF-32 and Myc sites (Shazman et al., 2014) and Centrimo (Bailey and Machanick, 2012) using TSS ± 100 bp of downregulated genes. BEAF-32, p = 2.4e-9. E-box, p = 2.1e-9.

(B) ChIP-seq read data showing binding of KDM5 (Liu and Secombe, 2015), Myc (Herter et al., 2015), and BEAF-32 (Nègre et al., 2010).

(C) Overlap of KDM5 regulated genes and those bound by BEAF-32 and those bound and regulated by Myc.

(D) Consensus Medea (Med; p = 5e-4) and Tram-track sites (Ttk; p = 2e-3) using TSS ± 100-bp upregulated genes and Centrimo.

(E) Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) view of KDM5 and Med ChIP-seq (Van Bortle et al., 2015).

(F) Overlap between KDM5-bound upregulated genes and those bound by Medea.

Similar analyses of the TSS ± 100-bp region of upregulated genes showed modest enrichment for two transcription factors, Medea and Tramtrack. Medea sites were observed surrounding the TSS (Med; p = 6.7e-3), whereas Tramtrack sites were downstream of the TSS (Ttk; p = 2e-3; Figure 5D). Ttk is a transcription factor with established roles in a number of processes, including neuronal and neuromuscular development (Chaharbakhshi and Jemc, 2016). Ttk ChIP data are not available, preventing us from verifying the enrichment for this transcriptional repressor at KDM5 targets. Medea interacts with Mad to mediate the transcriptional consequences of BMP/TGF-β signaling that is necessary for many developmental processes (Hamaratoglu et al., 2014). Using ChIP-seq data from cultured Kc cells in response to exogenous treatment with a Drosophila BMP, Decapentaplegic (DPP) (Van Bortle et al., 2015), we confirmed the overlap between KDM5 upregulated genes and those bound by Medea (p = 5e-4; Figures 5E and 5F). KDM5 may therefore act at a subset of BMP/Medea-regulated genes to facilitate transcriptional repression.

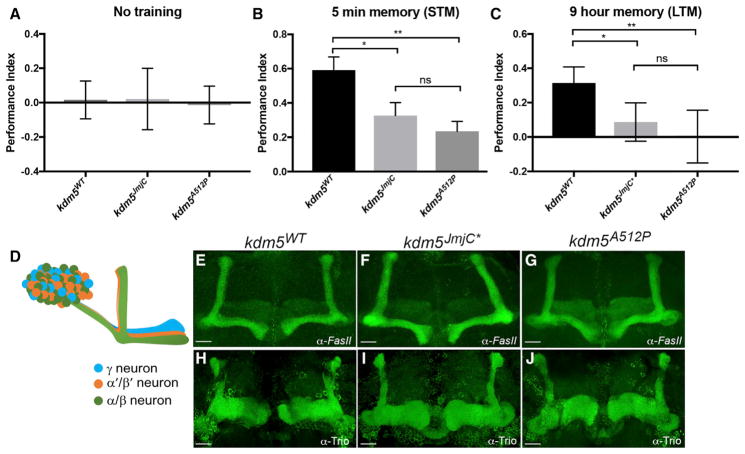

kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* Mutant Flies Show Short- and Long-Term Cognitive Phenotypes

To characterize the cognitive deficits of kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* flies, we tested their ability to form and/or retrieve memories using an appetitive associative olfactory learning assay. In this assay, flies are trained by pairing a sucrose reward with an air current containing 4-methylcyclohexanol (MCH) or octanol (OCT). The ability to remember the sucrose-associated odor is then tested using a T-maze by presenting both odors simultaneously in the absence of a reward for 2 min. A key advantage of this system is that a single round of training is sufficient to form short-term and long-term memories that are formed independently of each other through distinct mechanisms (Trannoy et al., 2011).

In the absence of training, kdm5WT, kdm5A512P, and kdm5JmjC* flies did not show a preference for either MCH or OCT (Figure 6A). After training, wild-type flies formed robust short- and long-term memories and show a clear preference for the sucrose-associated odor (Figures 6B and 6C). In contrast, kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* flies showed a significant defect at 5 min and 9 hr, and so had reduced short- and long-term learning and/or memory (Figures 6B and 6C). This assay relies on the ability to smell MCH and OCT, which flies find innately aversive compared to air. We therefore confirmed that, in the absence of training, kdm5WT, kdm5A512P, and kdm5JmjC* flies showed similar odor acuity (Figure S1). All genotypes also preferred sucrose solution over water, confirming this as an appropriate stimulus in the learning and memory assays (Figure S1). The KDM5A512P and KDM5JmjC* mutant proteins therefore disrupt the acquisition, processing, and/or retrieval of short- and long-term memories.

Figure 6. kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* Show a Learning and Memory Defect without Affecting MB Neuronal Morphology.

(A) When presented together, kdm5WT, kdm5JmjC*, and kdm5A512P do not prefer OCT or MCH in the absence of training.

(B) Five-minute (short-term) memory after one round of training. *p = 0.003; **p < 0.0001.

(C) Nine-hour (long-term) memory after one round of training. *p = 0.006; **p = 0.002.

(D) Diagram of MB α′/β′ and γ neurons and their cell bodies (Kenyon cells).

(E–G) Adult brains stained with anti-FasII to show α and β MB lobes of kdm5WT (n = 37) (E), kdm5JmjC* (n = 38) (F), and kdm5A512P (n = 51) (G). Scale bar, 20 microns.

(H–J) Anti-Trio staining of adult brains showing and γ lobes (and α′/β′ lobes) in kdm5WT (n = 38) (H), kdm5JmjC* (n = 31) (I), and kdm5A512P (n = 33) (J). Scale bar, 20 microns.

In (A)–(C), data are shown as mean ± SEM.

To determine whether kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutant flies had neuronal defects that could contribute to their cognitive deficits, we examined the morphology of the mushroom body, a paired structure in the adult brain that mediates olfactory learning and memory (Figure 6D). The α and β lobes of the mushroom body (MB) are necessary for acquisition and retrieval of long-term memory, and can be visualized using an antibody specific for the NCAM-like neural cell adhesion molecule Fasciclin II (FasII) (Kahsai and Zars, 2011). FasII antibody strongly stains α/β-lobe neuropil and weakly stains γ-lobe neuropil within the MB of the adult brain. Our analysis revealed that 100% of kdm5JmjC* mutant flies and 96% of kdm5A512P flies had morphologically normal α and β MB neurons (Figures 6E–6G). It should be noted that, although 4% (2/51 flies) of kdm5A512P flies showed α-lobe growth defects (Figure S1), it is improbable that this low frequency accounts for the learning and/or memory phenotypes observed. The acquisition and retrieval of short-term memories requires γ-lobe MB Kenyon cell neurons that express the Rho GEF Trio (Awasaki et al., 2000). Trio antibody strongly stains γ, as well as α′/β′ Kenyon cells, although we limited our analysis to the former for its role in short-term memory. Similar to our findings for α/β lobes, no gross morphological γ-lobe defects were observed in kdm5JmjC* or kdm5A512P brains (Figures 6H–6J). kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutant flies therefore do not have obvious physical defects that would explain their learning and memory deficits.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present key findings regarding the gene expression and cognitive defects of a Drosophila kdm5 allele (kdm5A12P) that is analogous to a KDM5C mutation found in ID patients (KDM5CA388P). The KDM5A512P mutation did not affect protein levels, distinguishing this model from the previous mouse KDM5C knockout model (Iwase et al., 2016; Scandaglia et al., 2017), and caused dramatic changes to the neuronal transcriptome and to the cognitive abilities of the fly. kdm5A512P mutants behaved indistinguishably from the demethylase-inactive strain (kdm5JmjC*), suggesting that loss of enzymatic activity is the primary defect associated with this mutation. Our analyses also showed that the demethylase activity of KDM5 is required for both gene activation and gene repression in a manner that correlates with distinct promoter elements. Together, our data are consistent with an evolutionarily conserved neuronal function for KDM5 family proteins.

Based on analyses of kdm5A512P in flies, human KDM5CA388P likely exerts its effects through a demethylase-dependent mechanism. This suggests that, while previous in vitro data of KDM5CA388P showed that this protein retained 45% of its demethylase activity (Iwase et al., 2007), the in vivo effect of this mutation is more dramatic. Because this mutation lies outside the catalytic JmjC domain, the molecular basis for the effect of KDM5A512P on enzymatic activity is not immediately obvious. Although the existing crystal structure data of KDM5 proteins do not include the residue affected by this missense mutation, it shows that domains in the N-terminal half of KDM5 family proteins interact extensively (Vinogradova et al., 2016). It is therefore likely that the tertiary structure of KDM5 places alanine 512 in close proximity to catalytically critical regions of the protein. The similarity between the phenotypes of kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* raises questions regarding the mechanism by which other alleles of KDM5 family genes lead to disease. It is possible that all missense mutations, independent of whether they reside within the JmjC domain, ultimately affect the histone demethylase activity of KDM5. This would be expected to result in the dys-regulation of a common set of target genes. In support of this possibility, six of the eight missense mutations in KDM5C that have observable in vitro demethylase activity defects lie outside the JmjC domain (Brookes et al., 2015; Iwase et al., 2007; Rujirabanjerd et al., 2010; Tahiliani et al., 2007). It is, however, noteworthy that one mutation, KDM5CD87G, showed only minimal defects to in vitro demethylase activity (Tahiliani et al., 2007) and the remaining mutations remain untested. It is therefore also possible that there is more than one mechanism by which mutations in KDM5 family proteins disrupt transcription to impair cognition.

As with previous transcriptome studies of KDM5 mutants across a number of species, the changes to gene expression observed in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutants were mild (Iwase et al., 2016; Liu and Secombe, 2015; Lopez-Bigas et al., 2008; Lussi et al., 2016). KDM5 therefore likely acts by “fine-tuning” the expression of numerous genes within pathways essential to neuronal function. Consistent with this model, the majority of direct KDM5 target genes that were downregulated genes in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutants have been previously implicated in ribosome assembly, structure, and function. Demonstrating the significance of these transcriptional changes, kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* mutant head, but not thorax, tissue showed attenuated translation. Short-term memory formation relies on the modification of existing proteins, whereas long-term memory is dependent on de novo protein synthesis to stabilize synaptic changes within the brain (Gal-Ben-Ari et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2012; Slomnicki et al., 2016). Thus, defective translation could contribute to the long-term learning and/or memory defects observed in our mutants either alone or in combination with the dysregulation of other genes involved in neuronal function. The link between translational regulation and cognitive impairment is highlighted by the observation that dysregulation of the Akt-mTOR pathway that regulates translation rates is found in patients with fragile X, Down syndrome, and Rett syndrome (Troca-Marín et al., 2012). Impaired ribosomal production or assembly is also linked to the neuronal dysfunction observed in Alzheimer’s disease and other tauopathies (Meier et al., 2016). KDM5-mediated regulation of growth pathways that impact neuronal function may be evolutionarily conserved, as brain tissue of KDM5C knockout mice showed dysregulation of genes required for growth, including ribosomal protein genes (Iwase et al., 2016).

While reduced protein synthesis provides a model to explain the long-term memory defects of kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* flies, new translation is not required for short-term memories. The chronic reduction in translation observed in mutant fly strains may, however, lower the levels of proteins necessary for short-term memory formation. Alternatively, defects in distinct pathways may cause the short- and long-term phenotypes. For example, genes required for the production and transmission of octopamine, a neurotransmitter required for short-term memory (Schwaerzel et al., 2003), were downregulated in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* flies. It is also possible that other dysregulated genes in kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* flies contribute to both the short- and long-term learning and/or memory defects.

Our analyses of two mutations that abolish the demethylase activity of KDM5 have provided key insights into potential mechanisms of transcriptional regulation. Promoter proximal H3K4me3 is found at transcriptionally active genes and is recognized by many proteins, including components of the transcriptional initiation machinery (Vermeulen et al., 2007). Because they demethylate H3K4me3, the enzymatic activity of KDM5 proteins is regarded as one that represses transcription. However, we find that KDM5 can directly activate or repress transcription in a demethylase-dependent manner. This is not due to the enzymatic activity of KDM5 varying at different targets, since levels of promoter-proximal H3K4me3 increase similarly at upregulated, downregulated, and unaffected genes. The observation that levels of promoter H3K4me3 are not a driving force in defining gene expression levels has been noted previously (Benayoun et al., 2014; Lussi et al., 2016).

Because we were unable to find enrichment for specific transcription factors at KDM5-regulated genes, KDM5 may be recruited downstream of other events that occur at its target promoters to facilitate transcriptional activation or repression. Supporting this model, we found that genes activated by KDM5 were often bound also by the transcription factor Myc and by the insulator protein BEAF-32. Indeed, Myc and BEAF-32 binding have previously been observed to correlate in cultured Drosophila Kc cells, although whether these proteins act to coordinate chromatin domains or transcriptional events is not known (Yang et al., 2013). We and others have also observed a physical interaction between KDM5 and Myc proteins in flies and mammalian cells (Li et al., 2010; Outchkourov et al., 2013; Secombe et al., 2007). However, because Myc and KDM5 peaks at co-regulated genes are not always coincident, it is not clear whether this interaction is important in the context of the adult brain. It is interesting to note that mutations in human N-Myc cause the cognitive disorder Feingold syndrome (Cognet et al., 2011), and knockdown of Drosophila Myc results in synaptic defects (Oortveld et al., 2013). Transcriptional cooperation between Myc and KDM5 in neurons may thus contribute to these cognitive phenotypes through the regulation of genes required for translation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly Strains

The gKDM5:HAWT and gKDM5:HAJmjC* transgenes are published (Navarro-Costa et al., 2016). gKDM5:HAA512P was similarly generated using the “thebestgene.com.” Other strains were from the Bloomington Stock Center. kdm5140 is a null (deletion) allele (described in detail elsewhere).

Immunostaining and Western Blot

Three- to 5-day-old adult flies were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 hr at 4°C. Brains were dissected, blocked in 5% normal donkey serum, incubated with anti-FasII, 1D4 (DSHB), or anti-HA at 4°C for 2 days and then incubated with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Cell Signaling) for 16 hr. Brains were mounted in Vectashield and imaged on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Western blots were carried out as previously described (Liu and Secombe, 2015).

Learning and Memory

Single-round training appetitive learning and memory assays were carried out as described previously (Trannoy et al., 2011) using 3- to 5-day-old flies and a T-maze purchased from CelExplorer Labs. Memory was quantified using a performance index (PI) calculated by subtracting the number of flies avoiding sucrose-associated odor from the number of flies preferring the sucrose-associated odor and dividing by the total number of flies. Ability to sense OCT and MCH was tested by calculating the PI for the odor versus air. Sucrose drive was quantified by starving flies for 16 hr and placing them in a T-maze apparatus for 5 min to choose between water-soaked and 2 M sucrose-soaked Whatman. At least 80 flies were used per experiment, which were carried out a minimum of five times.

Translation Quantification

Translation levels in adult brains were examined as previously described (Belozerov et al., 2014). Briefly, 2- to 5-day-old flies were starved for 6 hr and fed 600 μM puromycin (Sigma) or puromycin/35 mM cyclohexamide (Sigma) in a 3% ethanol/5% sucrose solution for 16–24 hr. Incorporated puromycin was quantified by western blot with anti-puromycin, 3RH11 (Kerafast), and normalized with histone H3 (Active Motif).

RNA-Seq

RNA-seq was carried out at the New York Genome Center. RNA was prepared in triplicate from kdm5WT, kdm5JmjC*, and kdm5A512P 3- to 5-day-old heads using Trizol and RNAeasy (QIAGEN). Libraries were prepared using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Preparation Kit. Samples were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer (v4 chemistry) using 2 × 50-bp cycles. Raw reads were aligned with STAR aligner and normalized, and differential expression was determined with DESeq2. GO analyses used GO David (Huang et al., 2009) and GOrilla (Eden et al., 2009). TSS analyses utilized MEME-suite (Bailey et al., 2009). Consensus DNA binding elements for transcription factors were from flyfactor (Shazman et al., 2014).

Chromatin IP

Anti-H3K4me3 and anti-HA (for KDM5:HA) ChIPs were carried out as described previously (Liu and Secombe, 2015). Primers sequences are provided in Table S2.

Statistical Analyses

Experiments were done in biological triplicate (minimum). R program was used for Fisher’s exact test; Student’s t test, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and Pearson correlation analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism, version 7. The accession number for the KDM5 ChIP-seq data is GEO: GSE70589 (Liu and Secombe, 2015), the accession number for the BEAF-32 ChIP-seq data is GEO: GSE16245 (Nègre et al., 2010), the accession number for the Medea ChIP-seq data is GEO: GSM1678114 (Van Bortle et al., 2015), and the accession number for the Myc ChIP and RNA-seq data is EMBL-EBI: E-MTAB-3209 (Herter et al., 2015).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Drosophila kdm5A512P is analogous to an intellectual-disability-causing mutation

kdm5A512P behaves similarly to a mutant allele that abolishes demethylase activity

kdm5A512P disrupts the transcription of genes important for cognition

kdm5A512P flies show short-term and long-term memory deficits

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Secombe laboratory members and Peter Gallant. We are grateful for funding from the March of Dimes (6-FY17-315) and NIH R01GM112783 to J.S., NIH Training Grant T32GM007288 to H.A.M.H., the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), the NY Genome Center, and the Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA013330).

Footnotes

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The accession number for the kdm5A512P and kdm5JmjC* RNA-seq data reported in this study is GEO: GSE100578.

Supplemental Information includes one figure and two tables and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2018.02.018.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.S., S.Z., and H.A.M.H. designed experiments. S.Z. generated fly strains and carried out learning tests and RNA-seq. J.S. and S.Z. analyzed RNA-seq. H.A.M.H. carried out puromycin and confocal analyses, C.D. did ChIP experiments, and H.M.B. characterized kdm5140. J.S., S.Z., and H.A.M.H. wrote the paper.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Awasaki T, Saito M, Sone M, Suzuki E, Sakai R, Ito K, Hama C. The Drosophila trio plays an essential role in patterning of axons by regulating their directional extension. Neuron. 2000;26:119–131. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylett CH, Ban N. Eukaryotic aspects of translation initiation brought into focus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372:20160186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Machanick P. Inferring direct DNA binding from ChIP-seq. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A, Santangelo S, Tan K, Catchpole S, Roberts K, Spencer-Dene B, Hall D, Scibetta A, Burchell J, Verdin E, et al. Breast cancer associated transcriptional repressor PLU-1/JARID1B interacts directly with histone deacetylases. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:265–275. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belozerov VE, Ratkovic S, McNeill H, Hilliker AJ, McDermott JC. In vivo interaction proteomics reveal a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Rack1 pathway regulating proteostasis in Drosophila muscle. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:474–484. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00824-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Ucar D, Mahmoudi S, Karra K, Wong ED, Devarajan K, Daugherty AC, Kundaje AB, Mancini E, et al. H3K4me3 breadth is linked to cell identity and transcriptional consistency. Cell. 2014;158:673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes E, Laurent B, Õunap K, Carroll R, Moeschler JB, Field M, Schwartz CE, Gecz J, Shi Y. Mutations in the intellectual disability gene KDM5C reduce protein stability and demethylase activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:2861–2872. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo RA, Õzkan E, Menon KP, Nagarkar-Jaiswal S, Lee PT, Jeon M, Birnbaum ME, Bellen HJ, Garcia KC, Zinn K. Control of synaptic connectivity by a network of Drosophila IgSF cell surface proteins. Cell. 2015;163:1770–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaharbakhshi E, Jemc JC. Broad-complex, tramtrack, and bric-à-brac (BTB) proteins: critical regulators of development. Genesis. 2016;54:505–518. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Agger K, Cloos PA, Pasini D, Rose S, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Hansen KH, Salcini AE, Helin K. RBP2 belongs to a family of demethylases, specific for tri-and dimethylated lysine 4 on histone 3. Cell. 2007;128:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cognet M, Nougayrede A, Malan V, Callier P, Cretolle C, Faivre L, Genevieve D, Goldenberg A, Heron D, Mercier S, et al. Dissection of the MYCN locus in Feingold syndrome and isolated oesophageal atresia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:602–606. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, Kou Y, Liu L, Fromer M, Walker S, et al. DDD Study; Homozygosity Mapping Collaborative for Autism; UK10K Consortium. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature. 2014;515:209–215. doi: 10.1038/nature13772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajan A, Barnes VL, Liu M, Saha N, Pile LA. The histone demethylase dKDM5/LID interacts with the SIN3 histone deacetylase complex and shares functional similarities with SIN3. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2016;9:4. doi: 10.1186/s13072-016-0053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal-Ben-Ari S, Kenney JW, Ounalla-Saad H, Taha E, David O, Levitan D, Gildish I, Panja D, Pai B, Wibrand K, et al. Consolidation and translation regulation. Learn Mem. 2012;19:410–422. doi: 10.1101/lm.026849.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant P. Myc function in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:a014324. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a014324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncçalves TF, Gonçalves AP, Fintelman Rodrigues N, dos Santos JM, Pimentel MM, Santos-Rebouças CB. KDM5C mutational screening among males with intellectual disability suggestive of X-linked inheritance and review of the literature. Eur J Med Genet. 2014;57:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafodatskaya D, Chung BH, Butcher DT, Turinsky AL, Goodman SJ, Choufani S, Chen YA, Lou Y, Zhao C, Rajendram R, et al. Multi-locus loss of DNA methylation in individuals with mutations in the histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase KDM5C. BMC Med Genomics. 2013;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:343–357. doi: 10.1038/nrg3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaratoglu F, Affolter M, Pyrowolakis G. Dpp/BMP signaling in flies: from molecules to biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;32:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herter EK, Stauch M, Gallant M, Wolf E, Raabe T, Gallant P. snoRNAs are a novel class of biologically relevant Myc targets. BMC Biol. 2015;13:25. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iossifov I, O’Roak BJ, Sanders SJ, Ronemus M, Krumm N, Levy D, Stessman HA, Witherspoon KT, Vives L, Patterson KE, et al. The contribution of de novo coding mutations to autism spectrum disorder. Nature. 2014;515:216–221. doi: 10.1038/nature13908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Lan F, Bayliss P, de la Torre-Ubieta L, Huarte M, Qi HH, Whetstine JR, Bonni A, Roberts TM, Shi Y. The X-linked mental retardation gene SMCX/JARID1C defines a family of histone H3 lysine 4 demethylases. Cell. 2007;128:1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase S, Brookes E, Agarwal S, Badeaux AI, Ito H, Vallianatos CN, Tomassy GS, Kasza T, Lin G, Thompson A, et al. A mouse model of X-linked intellectual disability associated with impaired removal of histone methylation. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1000–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LR, Amende M, Gurok U, Moser B, Gimmel V, Tzschach A, Janecke AR, Tariverdian G, Chelly J, Fryns JP, et al. Mutations in the JARID1C gene, which is involved in transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling, cause X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:227–236. doi: 10.1086/427563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LR, Bartenschlager H, Rujirabanjerd S, Tzschach A, Nümann A, Janecke AR, Spörle R, Stricker S, Raynaud M, Nelson J, et al. A distinctive gene expression fingerprint in mentally retarded male patients reflects disease-causing defects in the histone demethylase KDM5C. PathoGenetics. 2010;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1755-8417-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson C, Tumber A, Che K, Cain P, Nowak R, Gileadi C, Oppermann U. The roles of Jumonji-type oxygenases in human disease. Epigenomics. 2014;6:89–120. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Yoon BC, Holt CE. Axonal mRNA localization and local protein synthesis in nervous system assembly, maintenance and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:308–324. doi: 10.1038/nrn3210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahsai L, Zars T. Learning and memory in Drosophila: behavior, genetics, and neural systems. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;99:139–167. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387003-2.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Lee HG, Lim J, Han KA. Appetitive learning requires the alpha1-like octopamine receptor OAMB in the Drosophila mushroom body neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1672–1677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3042-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose RJ, Zhang Y. Regulation of histone methylation by demethylimination and demethylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Schmitz D. Cellular and system biology of memory: timing, molecules, and beyond. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:647–693. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Norman J, Shilatifard A, Shiekhattar R. Physical and functional association of a trimethyl H3K4 demethylase and Ring6a/MBLR, a polycomb-like protein. Cell. 2007;128:877–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Jones RS, Zhang Y. The H3K4 demethylase lid associates with and inhibits histone deacetylase Rpd3. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1401–1410. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01643-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Greer C, Eisenman RN, Secombe J. Essential functions of the histone demethylase lid. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefke R, Oswald F, Alvarado C, Ferres-Marco D, Mittler G, Rodriguez P, Dominguez M, Borggrefe T. Histone demethylase KDM5A is an integral part of the core Notch-RBP-J repressor complex. Genes Dev. 2010;24:590–601. doi: 10.1101/gad.563210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Secombe J. The histone demethylase KDM5 activates gene expression by recognizing chromatin context through its PHD reader motif. Cell Rep. 2015;13:2219–2231. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Greer C, Secombe J. KDM5 interacts with Foxo to modulate cellular levels of oxidative stress. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Bigas N, Kisiel TA, Dewaal DC, Holmes KB, Volkert TL, Gupta S, Love J, Murray HL, Young RA, Benevolenskaya EV. Genome-wide analysis of the H3K4 histone demethylase RBP2 reveals a transcriptional program controlling differentiation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussi YC, Mariani L, Friis C, Peltonen J, Myers TR, Krag C, Wong G, Salcini AE. Impaired removal of H3K4 methylation affects cell fate determination and gene transcription. Development. 2016;143:3751–3762. doi: 10.1242/dev.139139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machanick P, Bailey TL. MEME-ChIP: motif analysis of large DNA datasets. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1696–1697. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier S, Bell M, Lyons DN, Rodriguez-Rivera J, Ingram A, Fontaine SN, Mechas E, Chen J, Wolozin B, LeVine H, 3rd, et al. Pathological tau promotes neuronal damage by impairing ribosomal function and decreasing protein synthesis. J Neurosci. 2016;36:1001–1007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3029-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W, Hosseini M, Behjati F, Haas S, Jamali P, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Costa P, McCarthy A, Prudêncio P, Greer C, Guilgur LG, Becker JD, Secombe J, Rangan P, Martinho RG. Early programming of the oocyte epigenome temporally controls late prophase I transcription and chromatin remodelling. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12331. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nègre N, Brown CD, Shah PK, Kheradpour P, Morrison CA, Henikoff JG, Feng X, Ahmad K, Russell S, White RA, et al. A comprehensive map of insulator elements for the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishibuchi G, Shibata Y, Hayakawa T, Hayakawa N, Ohtani Y, Sinmyozu K, Tagami H, Nakayama J. Physical and functional interactions between the histone H3K4 demethylase KDM5A and the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:28956–28970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.573725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oortveld MA, Keerthikumar S, Oti M, Nijhof B, Fernandes AC, Kochinke K, Castells-Nobau A, van Engelen E, Ellenkamp T, Eshuis L, et al. Human intellectual disability genes form conserved functional modules in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outchkourov NS, Muiño JM, Kaufmann K, van Ijcken WF, Groot Koerkamp MJ, van Leenen D, de Graaf P, Holstege FC, Grosveld FG, Timmers HT. Balancing of histone H3K4 methylation states by the Kdm5c/SMCX histone demethylase modulates promoter and enhancer function. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropers HH, Hamel BC. X-linked mental retardation. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:46–57. doi: 10.1038/nrg1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rujirabanjerd S, Nelson J, Tarpey PS, Hackett A, Edkins S, Raymond FL, Schwartz CE, Turner G, Iwase S, Shi Y, et al. Identification and characterization of two novel JARID1C mutations: suggestion of an emerging genotype-phenotype correlation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:330–335. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandaglia M, Lopez-Atalaya JP, Medrano-Fernandez A, Lopez-Cascales MT, Del Blanco B, Lipinski M, Benito E, Olivares R, Iwase S, Shi Y, Barco A. Loss of Kdm5c causes spurious transcription and prevents the fine-tuning of activity-regulated enhancers in neurons. Cell Rep. 2017;21:47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaerzel M, Monastirioti M, Scholz H, Friggi-Grelin F, Birman S, Heisenberg M. Dopamine and octopamine differentiate between aversive and appetitive olfactory memories in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10495–10502. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-33-10495.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secombe J, Li L, Carlos L, Eisenman RN. The Trithorax group protein Lid is a trimethyl histone H3K4 demethylase required for dMyc-induced cell growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:537–551. doi: 10.1101/gad.1523007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shazman S, Lee H, Socol Y, Mann RS, Honig B. OnTheFly: a database of Drosophila melanogaster transcription factors and their binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D167–D171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomnicki LP, Pietrzak M, Vashishta A, Jones J, Lynch N, Elliot S, Poulos E, Malicote D, Morris BE, Hallgren J, Hetman M. Requirement of neuronal ribosome synthesis for growth and maintenance of the dendritic tree. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:5721–5739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.682161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Mei P, Fang R, Leonor T, Rutenberg M, Shimizu F, Li J, Rao A, Shi Y. The histone H3K4 demethylase SMCX links REST target genes to X-linked mental retardation. Nature. 2007;447:601–605. doi: 10.1038/nature05823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres IO, Kuchenbecker KM, Nnadi CI, Fletterick RJ, Kelly MJ, Fujimori DG. Histone demethylase KDM5A is regulated by its reader domain through a positive-feedback mechanism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6204. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trannoy S, Redt-Clouet C, Dura JM, Preat T. Parallel processing of appetitive short- and long-term memories in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1647–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troca-Marín JA, Alves-Sampaio A, Montesinos ML. Deregulated mTOR-mediated translation in intellectual disability. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;96:268–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu S, Teng YC, Yuan C, Wu YT, Chan MY, Cheng AN, Lin PH, Juan LJ, Tsai MD. The ARID domain of the H3K4 demethylase RBP2 binds to a DNA CCGCCC motif. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:419–421. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschach A, Lenzner S, Moser B, Reinhardt R, Chelly J, Fryns JP, Kleefstra T, Raynaud M, Turner G, Ropers HH, et al. Novel JARID1C/SMCX mutations in patients with X-linked mental retardation. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:389. doi: 10.1002/humu.9420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallianatos CN, Iwase S. Disrupted intricacy of histone H3K4 methylation in neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics. 2015;7:503–519. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortle K, Peterson AJ, Takenaka N, O’Connor MB, Corces VG. CTCF-dependent co-localization of canonical Smad signaling factors at architectural protein binding sites in D. melanogaster. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:2677–2687. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1053670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Voet M, Nijhof B, Oortveld MA, Schenck A. Drosophila models of early onset cognitive disorders and their clinical applications. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;46:326–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oevelen C, Wang J, Asp P, Yan Q, Kaelin WG, Jr, Kluger Y, Dynlacht BD. A role for mammalian Sin3 in permanent gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2008;32:359–370. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen M, Mulder KW, Denissov S, Pijnappel WW, van Schaik FM, Varier RA, Baltissen MP, Stunnenberg HG, Mann M, Timmers HT. Selective anchoring of TFIID to nucleosomes by trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4. Cell. 2007;131:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova M, Gehling VS, Gustafson A, Arora S, Tindell CA, Wilson C, Williamson KE, Guler GD, Gangurde P, Manieri W, et al. An inhibitor of KDM5 demethylases reduces survival of drug-tolerant cancer cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:531–538. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GG, Song J, Wang Z, Dormann HL, Casadio F, Li H, Luo JL, Patel DJ, Allis CD. Haematopoietic malignancies caused by dysregulation of a chromatin-binding PHD finger. Nature. 2009;459:847–851. doi: 10.1038/nature08036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Pelz C, Wang W, Bashar A, Varlamova O, Shadle S, Impey S. KDM5B regulates embryonic stem cell self-renewal and represses cryptic intragenic transcription. EMBO J. 2011;30:1473–1484. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Sung E, Donlin-Asp PG, Corces VG. A subset of Drosophila Myc sites remain associated with mitotic chromosomes colocalized with insulator proteins. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1464. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Peng Y, Lin D. The flexible loop L1 of the H3K4 demethylase JARID1B ARID domain has a crucial role in DNA-binding activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.