Abstract

The transition of macrophages from the pro-inflammatory M1 to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype is crucial for the progression of normal wound healing. Persistent M1 macrophages within the injury site may lead to an uncontrolled macrophage-mediated inflammatory response and ultimately a failure of the wound healing cascade, leading to chronic wounds. Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have been widely reported to promote M1 to M2 macrophage transition; however, it is unclear whether MSCs can drive this transition in the hypoxic environment typically observed in chronic wounds. Here we report on the effect of hypoxia (1% O2) on MSCs’ ability to transition macrophages from the M1 to the M2 phenotype. While hypoxia had no effect on MSC secretion, it inhibited MSC-induced M1 to M2 macrophage transition, and suppressed macrophage expression and production of the anti-inflammatory mediator interleukin-10 (IL-10). These results suggest that hypoxic environments may impede the therapeutic effects of MSCs.

Innovation

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have been tested in a variety of therapeutic applications involving inflammation and tissue injury. A potentially promising area is to treat injuries that fail to heal using current therapies, thus leading to refractory chronic wounds. While pre-clinical studies have shown that MSCs have the ability to modulate inflammation and improve wound healing, MSC therapeutic ability has yet to be demonstrated in human chronic wounds. Pre-clinical studies often exclude conditions such as disrupted blood flow and hypoxia that are attributed to chronic wounds. Herein, we report on an assay to demonstrate the impact of the local hypoxic wound environment on the ability of MSCs to modulate inflammation. This study shows that hypoxia decreases macrophage polarization from the pro-inflammatory M1 to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, needed to promote wound healing. Thus, the local injury environment must be taken into account when evaluating the therapeutic potential of MSCs.

Introduction

Wounds heal by a series of events including an inflammatory phase to recruit immune cells that kill bacteria and remove dead cells, followed by a proliferation phase where the cells that reform the damaged tissue components proliferate and migrate1. The mechanisms that control the transition from the inflammatory to the proliferative phases are complex and multi-faceted, and recent evidence suggests that macrophages play a key role in coordinating this process. For example, macrophages present at the wound site switch from a classically activated M1 to an alternatively activated M2 phenotype to resolve the inflammation1–3. Macrophages polarized towards the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, in the presence of inflammatory stimuli such as LPS or IFN-γ, produce high levels of pro-inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-232, 3. In contrast, anti-inflammatory stimuli such as IL-4 or prostaglandin-E2 (PGE2) drive macrophage polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype2, 4, 5. These M2 macrophages express high levels of the mannose receptor (CD206) and produce high levels of IL-10 and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1and low levels of TNF-α and IL-122, 6. Furthermore, M2 macrophages can be divided into subpopulations depending on their secretion and expression profiles, but in general they regulate cellular migration into the wounds and local cell proliferation2, 3, 6.

Disruption of the wound healing process in skin leading to non-healing chronic wounds is a common occurrence in skin of older individuals who have advanced diabetes and/or vascular disease. Although chronic wounds may have different etiologies, a common denominator is impaired blood flow that causes tissue hypoxia, impaired cellular functions, and ultimately cell death1–3, 7. As a result, chronic wounds appear to be “stuck” at the inflammatory stage1–3, 7. Sindrilaru et al. showed that macrophages isolated from chronic venous ulcers fail to differentiate into the M2 phenotype to initiate the tissue repair process3. Furthermore, ischemia impairs some of the bacterial killing mechanisms, such that ischemic chronic wounds are often infected8. The continual presence of bacterial- derived products also promotes persistent secretion of pro-inflammatory factors by macrophages3, 8.

Recent studies have shown that adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) secrete soluble factors that promote macrophage differentiation from the M1 to the M2 phenotype in vitro, including PGE22, 6. Furthermore, there is evidence that MSCs may promote wound healing in experimental animals, albeit these studies were carried out in acute wounds that are expected to experience normoxic conditions6, 9, 10. Herein, we explored if MSC-derived M2 macrophage polarization is impaired under conditions of hypoxia, as would be expected to occur in human chronic wounds.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture maintenance

Human bone marrow-derived MSCs were purchased from the Institute of Regenerative Medicine at Texas A&M at passage 1 and cultured as previously described11, 12. Briefly, MSCs were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), 1% v/v penicillin-streptomycin (pen-strep; Life Technologies) and 4mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies). Passage 3 cells were cultured until 70% confluency and immobilized in alginate sheets as previously described12. Briefly, 5 × 105 MSCs were mixed with 3% soluble alginate, placed in a 2 × 2cm PDMS mold, and submerged in a 500mM CaCl2 bath.

Primary peripheral blood-derived macrophages were isolated from peripheral blood as previously described13. Briefly, human whole blood was purchased from the Blood Center of New Jersey (East Orange, NJ) and mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. Following mononuclear cell separation, CD14+ monocytes were isolated using magnetic activated cell sorting. Ten million CD14+ monocytes were cultured in advanced RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% v/v FBS, 1% v/v pen-strep and 4mM L-glutamine for 2 hours to allow for cell attachment. Then cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells and cultured in fresh medium supplemented with 5ng/ml granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; R&D, Minneapolis, MN) for 7 days. CD14+ monocytes stimulated with GM-CSF produce a subset of macrophages expressing M1 phenotype13, 14. After 7 days in culture, cells were detached from the flasks using trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies) and 1 × 106cells/cryovial were frozen in 1 ml advanced RPMI 1640 medium with 40% v/v FBS, 1% pen-strep, 4mM L-glutamine, and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). For subsequent studies, macrophages were thawed, the viability was assessed using trypan blue staining and cells were plated and allowed to recover overnight before experiments commenced.

Cellular viability

M1 macrophages (5 × 104cells) were cultured in normoxia (5% CO2, 21% v/v O2, balance N2) or hypoxia (5% CO2, 1% v/v O2, balance N2) for 48 hours. The cells were then incubated at 37°C with 3μM calcein-AM + 6μM ethidium homodimer-1 and the nucleus counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) for 15 min in advanced RPMI 1640 with 10% v/v FBS, 1% pen-step and 4mM L-glutamine. The cells were washed briefly with medium and imaged on an Olympus fluorescent microscope using 10× objective. Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO) was used to quantify the number of live (green fluorescence), dead (red fluorescence), and total (blue fluorescence) cells to calculate the percent viability as described elsewhere12, 15.

Cytokine secretion

M1 macrophages (5 × 104cells/ml) or immobilized MSCs (2.5 × 105cells/ml) were cultured alone, with LPS or PGE2 for 48 hours in hypoxia or normoxia. The cell supernatant was collected and assayed for TNF-α (BioLegend, San Diego, CA), IL-10 (BioLegend), PGE2 (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI), and TGF-β1 (BioLegend) using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits.

MSC-conditioned medium

MSC-conditioned medium was made by culturing immobilized MSCs (2.5 × 105cells/ml) with LPS (MSC-CM+LPS) or without LPS (MSC-CM) for 48 hours in normoxia. For the control group (LPS), sham-conditioned medium was made by culturing cell-free alginate sheets with LPS for 48 hours in normoxia. Before M1 macrophages were cultured in the conditioned medium, 1μg/ml LPS was added to the medium to stimulate the macrophages. The control group in this study is defined as macrophages cultured in sham-conditioned medium.

Macrophage co-culture with MSCs

M1 macrophages (5 × 104cells/ml) were plated on 24mm and 3μm-pore size transwell inserts (Corning; Corning, NY) in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 1% pen-strep and 4 mM L-glutamine and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, the medium in the inserts was replaced with medium supplemented with 1μg/ml LPS and immobilized MSCs (2.5 × 105cells/ml) with LPS (MSC+LPS) or without LPS (MSC) or alginate sheets alone with LPS (LPS) was added to the bottom well. The cells were cultured in this configuration for 48 hours in normoxia or hypoxia and the medium was collected from the transwell and bottom well and assayed for TNF-α, IL-10, and TGF-β1. The control group in this study is defined as macrophages co-cultured with alginate sheets and LPS alone.

Western blot

M1 macrophages (2 × 105cells) cultured in normoxia or hypoxia and with or without LPS were treated with 1× RIPA Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA) with 1% protease inhibitor, 1% EDTA and 1% phosphatase inhibitor and then detached from the well using a cell scraper. Total protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Thermo Fisher). Equal amounts of total protein were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) followed by blotting to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat milk (Bio-Rad) or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma) in tris-buffered saline and tween-20 for 2 hours and then incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-1α antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After washing, the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Signals were detected by staining the membrane with SuperSignal™ west pico chemiluminescent (Thermo Fisher) for 5 min and bands digitized with a scanner.

Immunocytochemistry

M1 macrophages (5 × 104cells/ml) were cultured on glass bottom 24-well plates in normoxia or hypoxia for 48 hours with MSC-conditioned medium or sham conditioned medium with or without 1μg/ml LPS. Cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were washed 3 times and incubated in 1% w/v BSA (Sigma) + 10% v/v goat serum (Sigma) + 0.1% v/v Tween-20 (Sigma) + 0.1% v/v Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 hour to permeabilize the cell membranes and to block non-specific protein-protein binding. Cells were washed again and incubated with the anti-mannose receptor antibody (CD206; 1:100 dilution; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Then, the cells were incubated with the secondary antibody (1:500 dilution; Abcam) and the nucleus counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1:5000 dilution; Life Technologies) for 1 hour. Cells were imaged on an Olympus fluorescent microscope using a 10× objective. Slidebook software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations) was used to quantify the total number of cells (blue fluorescence) and CD206+ (green fluorescence) cells and calculate the percent of CD206+ cells.

Quantitative real-time PCR

M1 macrophages (2 × 105cells) were cultured in medium with 1μg/ml LPS in normoxia or hypoxia for 48 hours. After which, the medium was removed, cells were washed with PBS and lysed with QiaShredder (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was isolated and purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Equal amounts of RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using the Reverse Transcription System (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For qualitative PCR, the cDNA was combined with SYBR green master mix containing distilled water and primers to target genes and then polymerized using the PikoReal Real Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher). Specific primer sequences utilized for target genes are listed in table 1. Relative fold induction was calculated via the ΔΔCT method and values were normalized with GAPDH as the endogenous control.

Table 1.

Selection of primers for genes differentially expressed by macrophages

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| IL-10 | 5′ CATCGATTTCTTCCCTGTGAA 3′ | 5′ TCTTGGAGCTTATTAAAGGCATTC 3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′ ATGAGCACTGAAAGCATGATCC 3′ | 5′ GAGGGCTGATTAGAGAGAGGTC 3′ |

| IDO | 5′ CAAAGGTCATGGAGATGTCC 3′ | 5′ CCACCAATAGAGAGACCAGG 3′ |

| GAPDH | 5′ ACAACTTTGGTATCGTGGAA 3′ | 5′ AAATTCGTTGTCATACCAGG 3′ |

Statistical analysis

All numerical results are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis of three or more independent experiments were assessed using two-tail Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fischer post hoc analysis where p<0.05 represents statistical significance.

Results

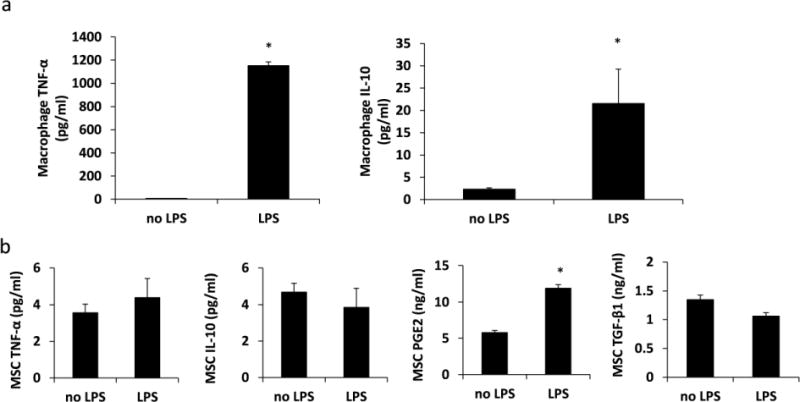

LPS augmented macrophage and MSC secretion

Primary macrophages were differentiated from monocytes isolated from human whole blood and treated with GM-CSF to acquire the M1 phenotype13, 14, 16. In general, macrophages secrete very little cytokine in the absence of a stimulus6, 17. Therefore, we first cultured M1 macrophages alone with 1μg/ml LPS under normoxia for 48 hours and examined their secretion of TNF-α and IL-10. As shown in figure 1A, LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages secreted significantly more TNF-α and IL-10 than M1 macrophages cultured without LPS. In addition, very little IL-10 was measured from these M1 macrophages cultured without LPS. The effect of LPS on MSC secretion of PGE2 was also examined because MSCs induce the M2 phenotype in macrophages by secretion of PGE24–6. Our results show that LPS induced a significant increase in MSC secretion of PGE2 but had minimal effect on MSC secretion of TNF-α, IL-10, and TGF-β1 (Figure 1B). Compared to LPS-stimulated macrophages, LPS-stimulated MSCs secreted very little TNF-α and IL-10 as noted by the low picogram levels in figure 1B.

Fig. 1.

LPS augments macrophage and MSC secretion. Immobilized MSCs or M1 macrophages were cultured with or without LPS for 48 hours under normoxia or hypoxia. (A) TNF-α and IL-10 proteins secreted by macrophages. N=4; *:p<0.0001 compared to no LPS (B) TNF-α, IL-10, PGE2, and TGF-β1 secreted by MSCs. N=3 – 6; *:p<0.0001 compared to no LPS.

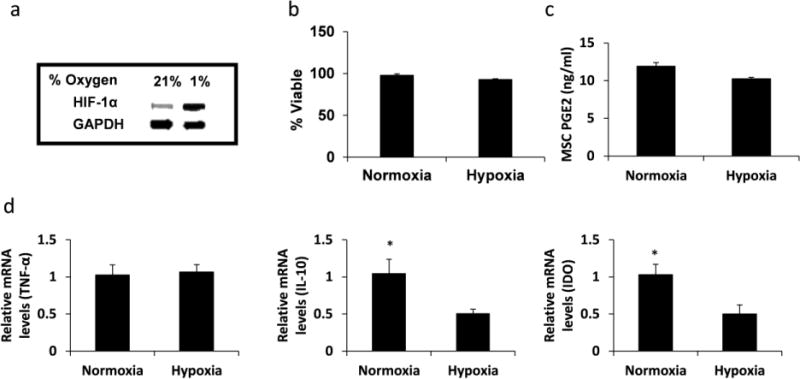

Hypoxia regulates macrophage function

LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages were cultured under hypoxia, at a level similar to that found in chronic wounds (1% v/v O2), to assess any changes in cell function and their ability to transition into the M2 phenotype18, 19. After 48 hours under hypoxia there was an increase in protein levels of HIF-1α (Figure 2A), a marker for cell adaptation to low oxygen tension. We also observed that after 48 hours under normoxia or hypoxia, macrophages remained over 90% viable with no significant difference in viability between the two groups (Figure 2B). Hypoxia had no effect on LPS-stimulated MSC secretion of PGE2 (Figure 2C) or macrophage expression of TNF-α (Figure 2D). However, figure 2d shows that hypoxia down-regulated macrophage expressions of IL-10 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). The down-regulation of IL-10 and IDO expressions suggests that hypoxia increased the M1 phenotype3, 14, 17, 20.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxia regulates macrophage function. LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages were cultured for 48 hours under normoxia or hypoxia. (A) HIF-1α protein expression in macrophages was determined by Western blot. GAPDH was used as the loading control. (B) Percent macrophage viability was determined by fluorescent live/dead staining. Calcein AM+/EthD-1− cells were deemed viable. N=3. (C) PGE2 secreted by MSCs. N=4. (D) TNF-α, IL-10, and IDO gene expressions by macrophages. N=4; *:p=0.05.

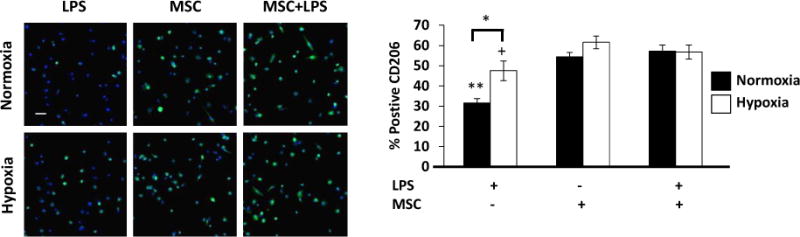

MSCs transition M1 macrophages towards the M2 phenotype

To assess the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs, LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages were cultured in MSC-conditioned medium for 48 hours under normoxia or hypoxia, and macrophage expression of CD206, a well-accepted M2 phenotype marker6, 21, 22, was determined by immunocytochemistry. Our results showed that in comparison to the control group (macrophages cultured without MSCs), MSC-conditioned media led to a significant increase in CD206+ macrophages under both normoxia and hypoxia (Figure 3). Under normoxia, there was a 72% increase in CD206 expression in the MSC group and an 81% increase in the MSC+LPS group compared to the control. However, hypoxia alone unexpectedly led to a significant increase in CD206 expression compared to normoxia, there was a 30% increase in CD206 expression in the MSC group and a 19% increase in the MSC+LPS group compared to the control. We also found no significant differences in macrophage expression of CD206 between the MSC and MSC+LPS groups. Additionally in both MSC groups, there was no significant difference in CD206 expression between cells cultured under normoxia or hypoxia.

Fig. 3.

MSCs upregulate CD206 expression on macrophages. LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages were cultured in MSC-conditioned medium or sham-conditioned medium for 48 hours under normoxia or hypoxia. (A) CD206 (M2 macrophage marker) expression in macrophages was examined by fluorescent microscopy. Scale bar = 20μm. Quantification of CD206+ cells. N=6; **:p<0.0001 compared to both MSC groups under normoxia; +:p<0.01 compared to MSC-CM group under hypoxia; *:p<0.001.

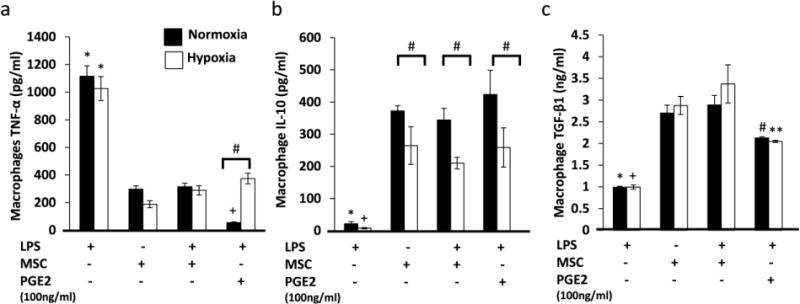

The phenotype of macrophages is determined by the markers expressed and by their production of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, which ultimately dictate their functions23, 24. To investigate if MSCs under hypoxia could induce the cytokine secretion profile characteristic of the M2 phenotype, LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages were co-cultured with MSCs for 48 hour in the transwell system under normoxia or hypoxia. Our results showed that under both normoxia and hypoxia, MSCs significantly decreased macrophage secretion of TNF-α compared to the control (Figure 4a). On the contrary, in the same co-culture, MSCs significantly increased macrophage secretion of IL-10 (Figure 4b) and TGF-β1 (Figure 4c). These results suggest that MSCs can transition the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype even under hypoxic conditions. However, unlike macrophage secretion of TGF-β1, their secretion of IL-10 was significantly greater when co-cultured with MSCs under normoxia compared to hypoxia.

Fig. 4.

MSCs induce an M2 secretion profile by macrophages. M1 macrophages were co-cultured with MSCs for 48 h under normoxia or hypoxia. (A) TNF-α protein secreted by macrophages. N=6; *:p<0.0001 compared to both MSC groups and the PGE2 group in both normoxia and hypoxia. +:p<0.05 compared to both MSC groups. #:p<0.05. (B) IL-10 protein secreted by macrophages. N=6; *:p<0.0001 compared to both MSC groups and the PGE2 group in normoxia. +:p<0.01 compared to both MSC groups and the PGE2 group in hypoxia. (C) TGF-β1 protein secreted by macrophages. N=6; *:p<0.001 compared to both MSC groups and the PGE2 group in normoxia. +:p<0.01 compared to both MSC groups and the PGE2 group in hypoxia.

Since the upregulation of IL-10 secretion by macrophages following co-culture with MSCs was not as dramatic compared to under normoxia (Figure 4b). Macrophages were also cultured with exogenous PGE2 at a concentration 10 times greater than concentrations secreted by MSCs. Our results show that exogenous PGE2 significantly increased macrophage secretion of IL-10 in both normoxia and hypoxia. In addition, compared to the MSC-treated groups, there was no significant difference in the level of IL-10 production by macrophages cultured in normoxia and hypoxia. Similarly to the MSC-treated groups, macrophages treated with PGE2 also secreted significantly more IL-10 in normoxia than in hypoxia.

Discussion

There is a plethora of evidence demonstrating that MSCs can induce macrophage transition from the M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype4–6, 17, 25. However, these studies were carried out under normoxic conditions, which is not the typical condition in infected tissues or chronic wounds. In chronic wounds, prolonged hypoxia due to impaired blood flow to the tissue significantly impairs cell function3, 7, 26. Specifically, wound macrophages fail to resolve inflammation and instead perpetuate the chronic inflammatory state3. This study investigated the interplay between classically activated or pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) under hypoxia in vitro.

Conventionally, monocytes that migrate into the wound differentiate into the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages due to the presence of interferon (IFN)-γ, LPS or GM-CSF6, 13, 16. These M1 macrophages are pro-inflammatory; they clear the wound from debris and pathogens and produce high levels of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-12, IL-23, and IL-6 and produce low levels of the anti-inflammatory IL-102, 3, 16. As wound healing progress, they transition into the M2 phenotype. M2 macrophages can be divided into 4 subsets and are characterized by their expression of specific markers and their production of specific cytokines. Even so, M2 macrophages generally secrete high levels of anti-inflammatory mediators such as TGF-β and IL-10, and are involved in tumor progression, resolution of inflammation, and tissue repair2, 16, 21. However, macrophages in chronic wounds fail to transition into the M2 phenotype and experience a prolonged M1 phenotype3. Therefore, a therapeutic strategy for chronic wounds is to drive macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype.

However, it is important to first understand the impact of hypoxia, a major feature of the chronic wound environment, on the M1 phenotype. As result, we evaluated the expressions of IDO, IL-10, and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages cultured under normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (1% O2). The enzyme IDO is a key regulator of the innate immune system; IDO catalyzes tryptophan degradation, thus limiting the growth of bacteria, parasites and viruses17, 27, 28. While macrophages do not constitutively express IDO14, 27, IDO expression can be induced by a variety of inflammatory stimuli such as IFN-γ14, 17, 27, 29. Our study showed that similar to IFN-γ, LPS induced IDO expression in macrophages cultured under normoxia. However, IDO expression was significantly suppressed in LPS-stimulated M1 macrophages cultured under hypoxia. This is consistent with Schmidt et al. who also showed that hypoxia diminished both IDO expression and activity in fibroblasts and tumor cells27. Modulation of IDO expression, in this manner, has been implicated in macrophage polarization14. Recently, Wang et al. demonstrated that overexpression of IDO in macrophages resulted in increased M2 markers and decreased M1 markers14. Their data is consistent with other authors who showed that IDO is overexpressed in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)29, which are a subset of M2 macrophages29–31. Wang et al. also showed that the knockdown of IDO expression was associated with increased M1 markers and decreased M2 markers14. From these studies, we can exclude the notion that hypoxia would induce an M2 phenotype similar to TAMs. Our results show that along with a decrease in IDO expression, there was also a suppression of the anti-inflammatory mediator, IL-10. The significant decreases in both IDO and IL-10 expressions and no change in TNF-α expression are indicative of M1 phenotype persistence as a result of hypoxia.

Several studies have shown that bone marrow-derived MSCs can promote macrophage transition from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype by PGE2 secretion4–6. PGE2 binds to EP4 receptors on macrophages and activate the MAPK/Erk signaling pathways, which lead to an increase in macrophage production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-105. Our results showed that, on the one hand, macrophages co-cultured with MSCs increased the number of M2 macrophages by increasing the level of M2-cytokine IL-10 and the growth factor TGF-β1, the expression of the M2-marker CD206, and decreased the level of M1-cytokine TNF-α. On the other hand, the MSC-induced increase in IL-10 production observed under normoxia was suppressed under hypoxia. Our results also showed that stimulating M1 macrophages with exogenous PGE2 at a concentration 10 times greater than concentration secreted by MSCs did not reverse the hypoxia-mediated suppression of IL-10 production by macrophages. However, both exogenous PGE2 and MSC treatment significantly increased macrophage secretion of TGF-β1 both in normoxia and hypoxia. The upregulation of TGF-β1 secretion by macrophages also suggest an upregulation in M2 transition.

Unlike, IL-10, there was no significant difference in TGF-β1 secretion in hypoxia as compared to normoxia. Other authors also found that hypoxia reduced basal and induced IL-10 protein and gene expressions32. Taken together, these data suggest that hypoxia significantly impairs IL-10 expression in macrophages, and this impairment is not ameliorated by MSCs. There is an abundance of pre-clinical data showing that MSCs have the ability to modulate inflammation and therefore may improve wound healing2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 12. However, this phenomenon was not always proven in human clinical trials33–35. This could be because most pre-clinical studies do not include hypoxia, which is often associated with wound healing. In our study, we found that hypoxia did not affect MSC secretion but did change their effect on host cells, as in our case the macrophages.

One limitation of this study is that M1 macrophages were cultured in hypoxia for only 48 hours, which is not an accurate depiction of the prolonged hypoxia observed in chronic wounds. Future studies will isolate macrophages from chronic wounds and assess MSCs’ ability to transition these prolonged inflammatory M1 macrophages into the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype.

Acknowledgments

The Charles and Johanna Busch Memorial Fund at Rutgers University supported this work. Renea Faulknor was supported by a Gates Millennium Scholarship. Paulina Krzyszczyk was supported by a Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) fellowship from the US Department of Education.

References

- 1.Diegelmann RF, Evans MC. Wound healing: an overview of acute, fibrotic and delayed healing. Front Biosci. 2004;9:283–289. doi: 10.2741/1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:383–396. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, Peter H, Hainzl A, Schatz S, Qi Y, Schlecht A, Weiss JM, Wlaschek M, Sunderkotter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:985–997. doi: 10.1172/JCI44490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maggini J, Mirkin G, Bognanni I, Holmberg J, Piazzon IM, Nepomnaschy I, Costa H, Canones C, Raiden S, Vermeulen M, Geffner JR. Mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells turn activated macrophages into a regulatory-like profile. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemeth K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Mayer B, Parmelee A, Doi K, Robey PG, Leelahavanichkul K, Koller BH, Brown JM, Hu X, Jelinek I, Star RA, Mezey E. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang QZ, Su WR, Shi SH, Wilder-Smith P, Xiang AP, Wong A, Nguyen AL, Kwon CW, Le AD. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells elicit polarization of m2 macrophages and enhance cutaneous wound healing. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1856–1868. doi: 10.1002/stem.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakytny R, Jude E. The molecular biology of chronic wounds and delayed healing in diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006;23:594–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boateng JS, Matthews KH, Stevens HN, Eccleston GM. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: a review. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:2892–2923. doi: 10.1002/jps.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H, Fu X, Ouyang Y, Cai C, Wang J, Sun T. Adult bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells contribute to wound healing of skin appendages. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:725–736. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Chen L, Scott PG, Tredget EE. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing through differentiation and angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2648–2659. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barminko J, Kim JH, Otsuka S, Gray A, Schloss R, Grumet M, Yarmush ML. Encapsulated mesenchymal stromal cells for in vivo transplantation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2747–2758. doi: 10.1002/bit.23233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faulknor RA, Olekson MA, Nativ NI, Ghodbane M, Gray AJ, Berthiaume F. Mesenchymal stromal cells reverse hypoxia-mediated suppression of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barminko JA, Nativ NI, Schloss R, Yarmush ML. Fractional factorial design to investigate stromal cell regulation of macrophage plasticity. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:2239–2251. doi: 10.1002/bit.25282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XF, Wang HS, Wang H, Zhang F, Wang KF, Guo Q, Zhang G, Cai SH, Du J. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in immune tolerance: focus on macrophage polarization of THP-1 cells. Cell Immunol. 2014;289:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nativ NI, Yarmush G, Chen A, Dong D, Henry SD, Guarrera JV, Klein KM, Maguire T, Schloss R, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML. Rat hepatocyte culture model of macrosteatosis: effect of macrosteatosis induction and reversal on viability and liver-specific function. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaguin M, Houlbert N, Fardel O, Lecureur V. Polarization profiles of human M-CSF-generated macrophages and comparison of M1-markers in classically activated macrophages from GM-CSF and M-CSF origin. Cell Immunol. 2013;281:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francois M, Romieu-Mourez R, Li M, Galipeau J. Human MSC suppression correlates with cytokine induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and bystander M2 macrophage differentiation. Mol Ther. 2012;20:187–195. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreml S, Szeimies RM, Prantl L, Karrer S, Landthaler M, Babilas P. Oxygen in acute and chronic wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen CK. Wound healing essentials: let there be oxygen. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Simonavicius N, Wu X, Swaminath G, Reagan J, Tian H, Ling L. Kynurenic acid as a ligand for orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR35. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22021–22028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bystrom J, Evans I, Newson J, Stables M, Toor I, van Rooijen N, Crawford M, Colville-Nash P, Farrow S, Gilroy DW. Resolution-phase macrophages possess a unique inflammatory phenotype that is controlled by cAMP. Blood. 2008;112:4117–4127. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dace DS, Khan AA, Kelly J, Apte RS. Interleukin-10 promotes pathological angiogenesis by regulating macrophage response to hypoxia during development. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Hematti P. Mesenchymal stem cell-educated macrophages: a novel type of alternatively activated macrophages. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:1445–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falanga V. Wound healing and its impairment in the diabetic foot. Lancet. 2005;366:1736–1743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt SK, Ebel S, Keil E, Woite C, Ernst JF, Benzin AE, Rupp J, Daubener W. Regulation of IDO activity by oxygen supply: inhibitory effects on antimicrobial and immunoregulatory functions. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelante T, Fallarino F, Bistoni F, Puccetti P, Romani L. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in infection: the paradox of an evasive strategy that benefits the host. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon MJ, Ghosh D, Gujja S. Signaling Circuits and Regulation of Immune Suppression by Ovarian Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Vaccines (Basel) 2015;3:448–466. doi: 10.3390/vaccines3020448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tjiu JW, Chen JS, Shun CT, Lin SJ, Liao YH, Chu CY, Tsai TF, Chiu HC, Dai YS, Inoue H, Yang PC, Kuo ML, Jee SH. Tumor-associated macrophage-induced invasion and angiogenesis of human basal cell carcinoma cells by cyclooxygenase-2 induction. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins SK, Egilmez NK, Suttles J, Stout RD. IL-12 rapidly alters the functional profile of tumor-associated and tumor-infiltrating macrophages in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:1357–1362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song J, Cheon SY, Jung W, Lee WT, Lee JE. Resveratrol induces the expression of interleukin-10 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in BV2 microglia under hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:15512–15529. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horwitz EM, Prockop DJ, Fitzpatrick LA, Koo WW, Gordon PL, Neel M, Sussman M, Orchard P, Marx JC, Pyeritz RE, Brenner MK. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Med. 1999;5:309–313. doi: 10.1038/6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prockop DJ, Prockop SE, Bertoncello I. Are clinical trials with mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells too far ahead of the science? Lessons from experimental hematology. Stem Cells. 2014;32:3055–3061. doi: 10.1002/stem.1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyndall A. Mesenchymal stem cell treatments in rheumatology: a glass half full? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:117–124. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]