Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme is the most aggressive primary brain tumor, with current treatment remaining palliative. Immunotherapies harness the body’s own immune system to target cancers and could overcome the limitations of conventional treatments. One active immunotherapy strategy uses dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccination to initiate T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. It has been proposed that cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) may play a key role in cancer initiation, progression and resistance to current treatments. However, whether using human CSC antigens may improve the anti-tumor effect of DC vaccination against human cancer is unclear. In this study, we explored the suitability of CSCs as sources of antigens for DC vaccination again human GBM, with the aim of achieving CSC-targeting and enhanced anti-tumor immunity. We found that CSCs express high levels of tumor associated antigens (TAAs) as well as major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Furthermore, DC vaccination using CSC antigens elicited antigen-specific T cell responses against CSCs. DC vaccination induced interferon (IFN) -γ production is positively correlated with the number of antigen-specific T cells generated. Finally, using a 9L CSC brain tumor model, we demonstrate that vaccination with DCs loaded with 9L CSCs, but not daughter cells or conventionally cultured 9L cells, induced CTLs against CSCs, and prolonged survival in animals bearing 9L CSC tumors. Understanding how immunization with CSCs generates superior anti-tumor immunity may accelerate development of CSC-specific immunotherapies and cancer vaccines.

Keywords: dendritic cell, vaccination, glioblastoma, cancer stem-like cells, cytotoxic T lymphocyte

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and most aggressive type of primary brain tumor, accounting for 52% of all primary brain tumor cases. Current treatment of GBM remains palliative and includes surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy(1), (2). Immunotherapies harness the body’s own immune system to target brain tumor and could overcome the limitations in conventional treatments (3–5). One of the most promising strategies may be active immunotherapy using dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccination to initiate T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity (6–10). In practice, vaccination strategies have often utilized DC pulsed with tumor-derived whole lysates/peptides as modalities to present a broad range of tumor antigens to T cells ex vivo in order to stimulate effective anti-tumor T-cell immunity (8). This process includes two stages: in vitro DC maturation and antigen loading and in vivo DC migration and antigen presentation in the draining lymph node (DLN). Human DCs are commonly generated from peripheral blood-derived monocytes, followed by a differentiation step to produce immature DCs (iDCs). The iDCs undergo maturation and antigen loading steps to produce mature DCs (11). Mature DCs loaded with tumor antigens are administrated subcutaneously into patients. The goal is to generate ex vivo a population of antigen-loaded DCs that stimulates robust and long lasting CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the patient with cancer.

Recent studies identifying cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) as brain tumor initiating cells may have implications for modifying GBM treatments, including DC vaccination-based immunotherapy (8, 12–14). Therapies targeting CSCs may prevent tumor recurrences seen after conventional radiation and chemotherapies. Furthermore, it is likely that certain stem cell markers expressed by CSCs may have distinct antigenicity and thus provide opportunities for enhanced immunotherapy. Some proteins expressed by CSCs are normally seen only in early development stages. Antibodies against the stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 was identified in a human patient (15). CSC-associated proteins may be used for cancer vaccination. It was reported recently that vaccination using Prostate Stem Cell Antigen induced long term protective immune response against prostate cancer without autoimmunity (16). Even without identification of specific antigens, CSCs can be a useful source of tumor antigens in DC vaccination-based immunotherapy. Using a mouse GL261 glioma model, Pellegatta et al demonstrated that vaccination with DCs loaded with glioma CSC antigens elicited robust anti-tumor T cell immunity (17). In this study, DC vaccination using CSC antigens cured up to 80% GL261 tumors, while DC vaccination using regular GL261 antigens cured none of the CSC-initiated tumors. However, whether using human CSC antigens may improve the anti-tumor effect of DC vaccination against human cancer is unclear.

In the current study, we investigate expression of tumor associated antigens (TAAs) and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules by GBM-derived CSCs. We report that CSCs express MHC I and increased levels of a range of TAAs. CSCs can be recognized by T cells generated after DC pulsed with CSC tumor antigens. DC vaccination induced interferon (IFN) -γ production is positively correlated with the number of antigen-specific T cells generated. Finally, using a 9L CSC brain tumor model, we demonstrate that DC vaccination with 9L CSC induced higher IFN-γ production than vaccination using parent cells and daughter cells and that DC vaccination with only 9L CSCs prolongs survival of tumor-bearing animals.

Materials and Methods

Primary culture of glioblastoma-derived cancer stem-like cells

Primary brain tumor spheres were cultured as previously described (14). Briefly, brain tumor stem-like cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with B-27 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 20 ng/ml of bFGF, 20 ng/ml of EGF (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ). Alternatively, dispersed brain tumor stem-like cells were grown on a laminin-coated surface in the same medium as described above. Primary human fetal neural stem cells were derived from primary cells obtained from Cambrex (East Rutherford, NJ). GBM cell line and adherent primary glioma cells were cultures in DMEM/F-12 containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Some frozen primary GBM tissues were used to compare gene expression profiles of BTSCs and their parental tumors.

Human glioblastoma cell antigen preparation

Human brain tumor cells were prepared following Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved Standard Operating Procedure. Fresh tumor specimen were divided and processed under sterile conditions. Tumors were cleaned and minced in a dissection medium (HBSS, 0.36% Glucose, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 0.03 mg/ml catalase, 6.6 mg/l deferoxamine, 25 mg/l N-acetyl cysteine, 94 mg/L cystine-Cl, 1.25 mg/L superoxide dismutase, 100U/mL Fungi-Bact, 0.11 mg/ml sodium pyruvate 10 mM HEPES). After digestion with trypsin-EDTA for 10 min at 37 °C, cells were washed and passed through 100 micron meshes. CSCs were isolated from primary tumor cells as described previously (8, 14). At lease one to three million cells in suspension were irradiated to prepare apoptotic CSCs as antigens. Tumor antigen protein concentrations were determined using Bio-Rad Protein Assay reagents.

Priming of human DCs with apoptotic CSCs

Human immature DCs were prepared from peripheral mononuclear blood cells (PBMC). PBMCs obtained from a HLA-A2+ healthy donor were prepared by Ficoll/Paque (Invitrogen) density gradient centrifugation. Cells were seeded (1×107 cells/3 ml/well) into 6-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% human AB serum, 2mM L-glutamine, 10mM HEPES, and antibiotics. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, adherent cells were used for DC generation as described. The non-adherent lymphocytes were stimulated with autologous DCs loaded with irradiated CSC line No.66 (HLA-A2 positive, CD133 positive) at the ratio of 10:1 (The CSCs and DCs were co-cultured overnight before they were seeded with lymphocytes). 300 IU/ml IL-2 was added to the cultures the next day and every 3 days thereafter. The lymphocytes were re-stimulated with DCs every week for up to three stimulations. The stimulated cells were tested for their ability to recognize antigen epitopes by incubating the stimulated cells with T2 cells pulsed with the epitopes as well as peptides derived from other tumor antigens and CD133 positive CSC lines. The stimulated cells (1×105) were incubated with 1×105 target cells for 24 h, and the release of IFN-γ (pg/ml) was measured by commercial ELISA kit (Endogen, Cambridge, MA). The percentage of CD133 specific CTLs in the stimulated cells were analyzed by tetramer technology.

Rat glioma cell antigen preparation and DC culture

Rat 9L glioma cell antigens are prepared using a procedure similar to the one described above. All animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. For rat immature DCs isolation, F344 Fisher rats were euthanized and bone marrow cells were collected by flushing femurs and tibias with RPMI 1640 media. Bone marrow cells were incubated with Interleukin 4 (IL-4) and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulation factor (GM-CSF) (150 U/mL, Peprotech, Rock Hill, NJ) with medium renewed every 2 days. After 7 days, cells were analyzed using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) with antibodies against CD11c, CD14, CD 80, CD86 and MHCII (obtained from BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Immature DCs of 90-100% purity were used for further studies. For rat DC stimulation, cells were stimulated by addition of LPS (50 μg/mL, from E. Coli 055:B5, Sigma, St. Luis, MO), or tumor lysate (100 μg/mL) for one day. Supernatant were taken after one day for further analysis.

Synthetic Peptides and HLA Typing

All of the peptides used in this study were synthesized by Macromolecular Resource (Fort Collins, CO). The identity and purity of each of the peptides were confirmed by mass spectrometer and high-performance liquid chromatography analysis. Peptides were dissolved in DMSO at 1 mM concentration for future use. GBM cells were stained with biotin-conjugated HLA-A2- or HLA-A1-specific monoclonal antibody (US Biological, Swampscott, MA) or biotin-conjugated isotype control antibody. After streptavidin-PerCP (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) staining for 30 min, the mean fluorescence intensity of HLA-A2 staining was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Tetramer Staining

Various antigen-specific peptide tetramers (phycoerythrin-peptide loaded HLA tetramer complexes) were synthesized (18, 19) and provided by Beckman Coulter (San Diego, CA). Specific CTL clone CD8+ cells were resuspended at 105 cells/50 μl fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (phosphate buffer plus 1% inactivated fluorescence-activated cell-sorting buffer). Cells were incubated with 1 μl of tHLA for 30 min at room temperature, and incubation was then continued for 30 min at 4°C with anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (Becton Dickinson). Cells were washed twice in 2 ml of cold fluorescence-activated cell-sorting buffer before analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Becton Dickinson).

T cell stimulation and cytotoxic T cell assays

For human cells, cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) precursor frequency was determined in order to assess effective immunization to autologous tumor cells. PBMCs (1× 106 cells/mL) were stimulated in 10% human AB serum with 1× 106 /mL irradiated CSCs-pulsed DC, with recombinant human IL-2 (300 units/mL) added on day 2. Expanded CTL from PBMC were re-stimulated on day 11 with 150 μg/mL tumor antigens for 2 hrs. RNA was extracted and IFN-γ production was analyzed using ELISA assays. Controls include DC alone, PBMC alone, and tumor antigens with PBMC. Rat T cell stimulation and CTL assays were performed in a similar fashion. FACS analysis of CD69 and MHC class II expression were performed for alloreactive T cell activation index.

Real-time RT-PCR, ELISA and FACS analysis

For quantitative PCR, total RNA was isolated from stimulated cells using Trizol (GIBCO invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and transcribed using random hexamers. Cytokines and reference cDNA and quantified plasmid DNA standards were amplified using qPCR primers or probes (Qiagen, Alameda, CA), with greater than a 1.5 fold increase in CD8-normalized IFN-γ production following vaccination indicating a positive response. ELISA analysis was performed to determine IFN-γ production using ELISA kits from R&D Systems following the manufacturer’s instructions. DCs and PBMCs were rinsed in FACS buffer (PBS with 1%FCS, 0.1% w/v sodium azide) and incubated with Fc Block (BD Bioscience) for 20 min on ice, and stained with FITC- or PE-conjugated antibodies (CD86, CD69, MHC class II, from BD Biosciences) for 30 min on ice. After rinse of three times, cells were analyzed using a FACScan system (BD Biosciences).

DC vaccination in a rat glioma model

Adult F344 Fisher rats were anesthetized and placed in the stereotactic frame. The skin was cut with a scalpel and the skull penetrated using a dental drill. A needle was placed 5 mm deep at the following coordinates from bregma (anterior-posterior +1 mm; medial-lateral-3 mm; dorsal-ventral-5 mm). Duramater was punctured at the specific site of injection. Initial tumor inoculums were prepared using 25,000 luciferase-labelled 9L-gliosarcoma cells. For DC vaccination, animals were followed up at day 7, 14, and 21 with subcutaneous DC vaccinations into the flank using manual restraint of the animal or intracranially. Before vaccination, 50,000 freshly cultured immature dendritic cells were incubated with tumor antigens acid-eluted from tumor cells or saline control for one day.

Survival and statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with a SAS statistical software package. Means of at least three independent experiments were reported with standard deviations. The estimated probability of survival was be demonstrated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Mantel Cox log-rank tests were used to compare curves between study and control groups. Any P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of tumor-associated antigens in glioblastoma-derived cancer stem-like cells

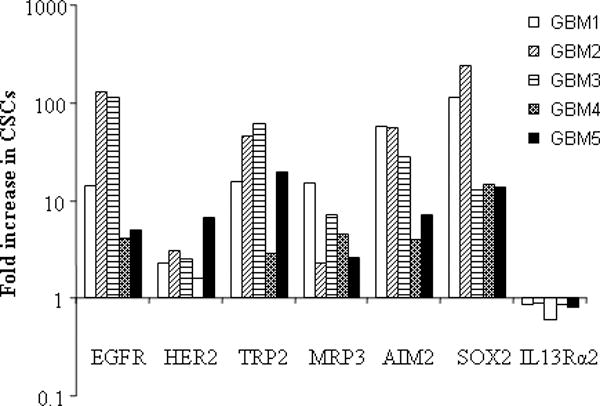

We had previously isolated CSCs from human GBM and demonstrated their self-renewal capability and multi-potent differentiation in vitro and tumor-initiating ability in vivo(8, 14). Although these CSCs manifest different gene expression profiles and signal pathway activities (14), they share the expression of neural stem cell marker nestin and the cell surface marker CD133 (Figure 1A). Another cell surface marker LeX/CD15 was recently identified in murine neural stem cells (5). Flow cytometry analysis indicated that most of the CD133 positive CSCs also express CD15 (Figure 1B). The expression of CD133 and CD15 in the differentiated daughter cells, however, is greatly reduced (Supplemental Figure 1). To study whether CSCs express certain TAAs, we measured the expression levels of several GBM-associated tumor antigens in both conventional cultured adherent cells and corresponding CSCs. We found that both adherent cells which contain differentiated daughter cells and CSCs express EGFR, HER2, TRP2, MRP3, AIM2, SOX2, IL13Rα2, but the expression levels were two- to over 200-fold higher in CSCs than those in adherent cells, with the exception of IL13Rα2 whose expression levels are comparable in both adherent cells and CSCs (Figure 2). Some of these tumor antigens were shown in our previous studies to be expressed in human GBM and recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (7, 18, 19). The higher expression of TAAs in CSCs suggested that CSCs may be a better source of tumor antigens in DC vaccination-based immunotherapy.

Figure 1.

Glioblastoma-derived spheres are enriched in cells expressing cancer stem-like cell markers. A. Glioblastoma-derived cancer stem-like cells express CD133, and Nestin. Primary cultured glioblastoma-derived spheres were processed for immunofluorescence staining using antibodies against human CD133 and Nestin. DAPI staining was used to reveal cell nuclei. B. Glioblastoma-derived spheres are enriched in cells expressing both CD133 and CD15. Glioblastoma-derived spheres were processed into single cell suspension before FACS analysis using antibodies against human CD133 and CD15.

Figure 2.

Elevated expression of tumor-associated antigens in human glioblastoma-derived stem-like cells. Representative tumor-associated antigen expression in glioblastoma multiforme cancer stem-like cells (GBM1-5). Cancer stem-like cells single cell suspension was stained with specific monoclonal antibodies to each tumor-associated antigens and an isotype-matched control antibody, followed by FACS analysis. Results are given as the ratio of antigen expression levels in CSCs to those in daughter cells.

Expression of class I MHC molecules on cell surface of cancer stem-like cells

Tumor antigens must be presented with class I MHC molecules to be recognized by specific CTLs (20). Tumor cells may down-regulate MHC expression through epigenetic modifications or other mechanisms to escape immune surveillance. To determine whether class I MHC molecules are expressed by GBM CSCs, the expression of MHC class I and class II was analyzed on three cancer stem cell lines and normal neural stem cells for comparison. As shown in Figure 3, all three CSCs clearly express class I MHC molecules on the cell surface, while its expression on neural stem cells (NSCs) is undetectable. Unexpectedly, a small population of each CSC line also express class II MHC molecules. Class II MHC expression is usually limited to the antigen presenting cells (DCs, macrophages, and B cells). The significance of its expression in CSCs is unknown. We also detected similar expression of MHC molecules in adherent GBM tumor cells (data not shown). Therefore, CSCs express both TAAs and relevant MHC molecules that are necessary for CTL recognition and activation.

Figure 3.

Glioblastoma-derived stem-like cells express class I MHC molecules on the cell surface. A subset of CSCs expresses both class I and class II MHC molecules. Single cell suspension of neural stem cells (NSC) and cancer stem-like cells (CSC3-5) was stained with specific antibody to class I MHC (HLA-A,B,C), class II MHC (HLA-DR) and an isotype-matched control antibody, followed by FACS analysis. Results were representative of three independent experiments.

Vaccination with dendritic cells loaded with cancer stem-like cell-associated antigens elicits antigen-specific T cell response

To determine the effect of DC vaccination using antigens enriched in CSCs, DCs isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of a HLA-A2+ healthy donor were primed in vitro using autologous dendritic cells pulsed with irradiated apoptotic CSCs. These human mature DCs express costimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, and CD40 (Supplemental Figure 2). The expression patterns of costimulatory molecules by DCs after the culture with CSCs or their daughter cells are similar to each other (Supplemental Figure 3). The lymphocytes were re-stimulated with DCs every week for up to three stimulations. The stimulated cells were then tested for their ability to recognize specific epitopes derived from TRP2, HER2, IL13Rα2, and SOX2 by incubating the stimulated cells with T2 cells pulsed with the epitopes. As shown in Figure 4A, tumor antigen-loaded DCs stimulated Th1 response and induced significant IFN-γ production. Next, we tested the effect of DC vaccination using three different CSCs and NSCs as antigens. Stimulation of PBMCs using each of the three CSC antigens induced significant T cell responses as indicated by robust IFN-γ production in response to analysis stimulation (Figure 4B). Although some antigens (such as EGFR) were shared between CSCs and NSCs, co-culturing with NSCs did not induce immune response and IFN-γ production, consistent with the fact that NSCs do not express MHC molecules. These data suggested that DC vaccination using apoptotic CSCs can elicit a strong specific T cell response.

Figure 4.

Dendritic cell vaccination using cancer stem-like cell antigens generates antigen-specific Th1 response. A&B. IFN-γ release by antigen-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognizing tumor-associated antigens HER-2, TRP, CD133, IL13Rα2, and Sox2 (A) and IFN-γ release by CD8+ CTLs after vaccination with different CSCs (B). 1 × 105 clonal CTL cells were incubated with 1 × 105 HLA-matched tumor cells as compared with CTL cells incubated with 1 × 105 control cells. ** p< 0.01 (compared with control groups). C. Assessment of tumor-associated antigen-specific T cell clones by HLA/peptide tetramer staining. HER-2, TRP, CD133, IL13Rα2, and Sox2-specific CTL clones (1 × 105 cells) were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated peptide/HLA tetramer at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were then incubated with antibody against CD8 for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were then examined by fluorescence-activated cell-sorting analysis using 10,000 events/sample. Generation of antigen-specific CTL is positively correlated with Th1 response as indicated by IFN-γ production (coefficient R2=0.86).

To determine whether the stimulated T cells contain antigen-specific CTLs, we performed tetramer analyses using antigen tetramers. Figure 4C shows that tumor antigen specific CTLs were present in the in vitro stimulated T cells. The percentages of antigen-specific CTLs vary from 0.3% to 1.2% (Figure 4C). Clearly, optimization of peptide and tetramer designs and conditions may improve the detection of antigen-specific CTL generation. Finally, the percentage of antigen-specific CTLs is positively correlated with antigen-loaded DC-induced IFN-γ production (R2=0.86) (Figure 4D), suggesting that DC-induced IFN-γ production likely resulted from activation of antigen-specific CTLs.

To test whether there is any difference in tumor cell endocytosis levels by DCs after culture with CSCs and their daughter cells, which may contribute to differential TAA presentation and immune responses, we incubated DCs with PKH26-labeled apoptotic CSCs or their daughter cells and determined endocytosis frequencies in DCs. We found that there is no significant difference in endocytosis activities between DCs cultured with apoptotic CSCs and their daughter cells (Supplemental Figure 4), suggesting that superior immune responses after vaccination with CSCs rather than daughter cells are likely due to improved target cell recognition by antigen-specific CTLs.

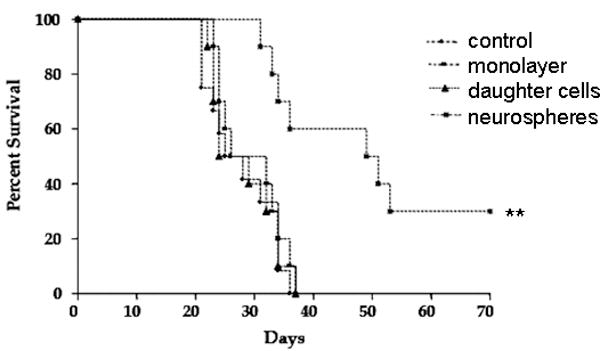

DC vaccination using cancer stem-like cell-associated antigens prolongs survival in a 9L brain tumor model

To investigate whether DC vaccination targeting CSC may induce anti-tumor immunity in vivo and improve survival for tumor-bearing animals, we established a 9L CSC brain tumor model for DC vaccination studies. Previously, we isolated CSCs from 9L gliosarcoma cell line and demonstrated that 9L CSCs can initiate aggressive and chemo-resistant brain tumors (21). DCs were isolated from Fisher rat bone marrow, and were pulsed with media (as control) or acid-eluted tumor peptides from either 9L gliosarcoma cells grown in monolayer, 9L-CSCs, or 9L CSC daughter cells. Animals bearing intracranial 9L gliosarcoma were vaccinated subcutaneously on days 7, 14, and 21 post tumor implantations. Rats bearing 9L gliosarcoma vaccinated with un-pulsed DC vaccine all expired with a median survival of 26.5 days. Rats vaccinated with DCs pulsed with 9L or 9L daughter cells also expired with median survival dates of 32 and 29 days, respectively. In contrast, rats vaccinated with DC-9L CSCs had a median survival of 50 days when survival was monitored up to 70 days post inoculation at which point 30% of the rats were still alive (Figure 5). DC-9L CSC vaccinated rats had slowly growing tumors which had increased infiltration of CD4+ T lymphocytes in brain sections (data not shown). The data demonstrate that DC immunotherapy could induce specific immune response targeting cancer stem like cells and significantly prolong survival in a rat brain tumor model, suggesting that immunotherapy selectively targeting cancer stem cells could be a novel effective strategy to treat malignant glioma patients.

Figure 5.

Therapeutic effect of neurosphere-pulsed DC against intracranial 9L tumor in adult rats. Rats were injected intracranially with 25000 9L glioma cells on day 0 and were vaccinated s.c. on days 7, 14, and 21 with different tumor antigen pulsed dendritic cell vaccines: control (DC only), monolayer, daughter cells, and neurospheres (n=10 for each group). Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that rats treated with 9L neurosphere lysate-pulsed DC have longer survival than the other groups (** p=0.0015). The surviving animals with CSC vaccination were sacrificed after 70 days and slowly growing brain tumors were detected.

To determine whether the relative protective effect of 9L CSC DC vaccination on survival is due to tumor-specific immunity, we performed a CTL assay. IFN-γ mRNA levels in the CD8 cells were measured using real-time PCR. As shown in Table 1, re-stimulated splenocytes from rats treated with 9L CSC-pulsed DCs showed significantly higher level of IFN-γ mRNA in response to target than re-stimulated splenocytes from rats treated with 9L monolayer cells or 9L daughter cells. The higher IFN-γ mRNA response in the NS-DC vaccinated group is consistent with the higher survival rate observed in the same group as shown in Figure 5.

Table 1.

IFN-γ production after immunization with 9L-CSC-pulsed DC. Splenocytes from tumor bearing rats were re-stimulated with IL-2 for 11 days followed by re-exposure to a final 9L tumor cell target (9L monolayer cells, 9L neurospheres, or 9L daughter cells) or a blank. Only splenocytes from neurosphere-vaccinated rats released high level of IFNγ when re-exposed to neurospheres.

| Samples | Mean threshold cycles (Ct) | Mean threshold difference (ΔCt) | Fold change in normalized IFN-γ (2ΔCt) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD8 | IFN-γ | ||||

| control | No target | 23.1 | 26.3 | −3.2 | 1.32 |

| Target | 23.7 | 26.5 | −2.8 | ||

| 9L-monolayer | No target | 23.4 | 24.4 | −1.0 | 1.15 |

| Target | 24.3 | 25.1 | −0.8 | ||

| 9L-daughter cells | No target | 24.8 | 28.8 | −4.0 | 1.41 |

| Target | 22.9 | 26.4 | −3.5 | ||

| 9L-neurospheres | No target | 23.2 | 28.2 | −5.0 | 5.66 |

| Target | 22.8 | 25.3 | −2.5 | ||

Discussion

Increasing evidence supports the notion that a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells is responsible for cancer progression, therapy resistance and relapse. To inhibit tumor recurrence more effectively, it would behoove any cancer therapy, including immunotherapy, to target the cancer stem cell. In this study, we build on our extensive experience of DC vaccination for human GBM patients, and explore the possibility of targeting CSCs in DC vaccination, using both human samples and a syngeneic animal brain tumor model. Our results demonstrate that GBM-derived CSCs express a range of TAAs and class I MHC molecules that are critical for immune recognition. The expression levels of some TAAs in CSCs are as high as over 200 fold of the levels in daughter cells. Importantly, vaccination with DCs loaded with CSCs antigens induced antigen-specific Th1 immune response. Finally, we tested DC vaccination using 9L CSC tumor antigens in a 9L CSCs brain tumor model and achieved robust anti-tumor T cell immunity and a significant survival benefit.

Two recent studies using animal models demonstrated the potential of DC vaccination targeting CSCs in cancer immunotherapy (16, 22). In their study of DC vaccination using GL261 neurospheres in a mouse brain tumor model, Finocchiaro and collegues found that immunization with DCs loaded with GL261 neurospheres cured 60-80% animals with glioma, while vaccines of DCs loaded with adherent GL261 cells cured only 50% of GL261 tumors and none of the GL261 neurospheres initiated tumors (17). They also reported robust tumor infiltration by CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Although there is no tumor antigen characterization, antigen presentation function or other mechanistic data in this study, it indicated the distinct potential of CSCs in inducing anti-tumor immunity. In another recent study of prostate cancer, Garcia-Hernandez Mde et al vaccinated with prostate stem cell antigen in mice bearing progressing prostate cancer and found induced MHC expression, cytokine production, lymphocyte infiltration and long term protection again prostate cancer (16). Both cancer vaccination studies in murine models support the hypothesis that CSCs-derived whole lysates or CSC-associated antigens may be superior to conventional tumor antigens in generating therapeutic anti-tumor effects. Consistent with these studies, our data on cancer immunization using 9L CSCs in a rat model indicated that vaccination with DCs loaded with only 9L CSCs antigens, but not the daughter cell antigens, induced CTL responses against CSCs and significantly extended survival of animals bearing 9L CSC tumors.

One key point from our study is that CSC-targeting DC vaccination appears to be superior not only in experimental murine models, but also in human brain tumors. Due to the known difference in cancer immunity between murine species and human, it is important to investigate CSC-targeting DC vaccination in human cancer and compare the results in human cancer study to those in murine models. In our study, we took advantage of several well characterized human GBM-derived CSCs (8, 14) and explored the possibility of DC vaccination using CSC antigens against human brain tumors. Significantly, we found that these CSCs highly express a range of known TAAs as well as MHC molecules. Immunization with apoptotic CSCs induced an antigen-specific Th1 response. These data suggest that CSCs may be better sources of antigens for cancer immunization that conventionally cultured tumor cells. It is to be seen whether this CSC-targeting vaccination will generate better anti-tumor clinical effects in human GBM patients. It is important that CSC-targeted DC vaccination should not lead to immune reaction to normal cells that may express common antigens. However, multiple mechanisms may exist that spare normal cells from such side effects. We found that NSCs had very low expression of cell surface MHC molecules. NSCs may also evade immune attack due to decreased expression of co-stimulatory proteins(23). We are in the progress of initiating a clinical trial to study the safety and efficacy of DC vaccination using CSC antigens.

To date there is very limited number of studies of CSC-targeting DC vaccination in animal models or in patients. And detailed immunological analysis data on the development of anti-tumor immunity after DC vaccination are not available. Questions remain regarding mechanisms underlying the apparent superior outcomes from CSC-targeting DC vaccination. For example, is there any difference between CSC antigens and conventional tumor lysates in promoting DC maturation and polarization, or in effector cell differentiation and memory T cell generation in vivo? Although higher expression of TAAs in CSCs, as shown in our study, may be one factor contributing to the outcomes, it is likely other factors in addition to TAA expression levels also play a role. Finally, outcomes of DC vaccination may be improved when it is administered in combination with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other therapies (9, 24, 25).

In summary, we explored the suitability of CSCs as sources of antigens for DC vaccination again human GBM, with the aims of achieving CSC-targeting and better anti-tumor immunity. We found that CSCs express increased levels of TAAs as well MHC molecules. Furthermore, DC vaccination using CSC antigens elicited a potent antigen-specific Th1 response. Finally, we show that vaccination with DCs loaded with 9L CSCs, but not the daughter cells or conventionally cultured 9L cells, induced CTLs that recognized CSCs and prolonged survival animals bearing 9L CSC tumors. Understanding how immunization with CSCs generates superior anti-tumor immunity may help develop novel and more effective cancer immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Iman Abdulkadir for technical assistance in bone marrow cell culture and animal experiments. This work was supported in part by R01 NS048959.and grant NS048879 to J.S.Y.

Footnotes

Contributions:

QX: concept and design; culture and characterization of human CSCs; human dendritic cell characterization; rat DC vaccination model and animal experiments; Writing the manuscript. GL: human CSC expression of TAA, IFN-γ assays, tetramer assays and data analysis. XY: human dendritic cell endocytosis; supporting roles in tissue culture, rat DC vaccination model and animal experiments; MX: PCR and FACS experiments with GL. HW: human DC culture and antigen loading. JJ: supporting DC culture and genotyping. BK: assisting with animal experiments. KLB: financial support and material. JSY: concept and design; advisor and supervising role; co-writing.

References

- 1.Reardon DA, Rich JN, Friedman HS, et al. Recent advances in the treatment of malignant astrocytoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1253–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang XJ, Choi Y, Sackett DL, et al. Nitrosoureas inhibit the stathmin-mediated migration and invasion of malignant glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5267–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehtesham M, Black KL, Yu JS. Recent progress in immunotherapy for malignant glioma: treatment strategies and results from clinical trials. Cancer Control. 2004;11:192–207. doi: 10.1177/107327480401100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okada H, Low KL, Kohanbash G, et al. Expression of glioma-associated antigens in pediatric brain stem and non-brain stem gliomas. J Neurooncol. 2008;88:245–50. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eguchi J, Hatano M, Nishimura F, et al. Identification of interleukin-13 receptor alpha2 peptide analogues capable of inducing improved antiglioma CTL responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5883–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liau LM, Black KL, Martin NA, et al. Treatment of a patient by vaccination with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with allogeneic major histocompatibility complex class I-matched tumor peptides. Case Report Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e8. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.9.6.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu G, Khong HT, Wheeler CJ, et al. Molecular and functional analysis of tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-2 as a cytotoxic T lymphocyte target in patients with malignant glioma. J Immunother. 2003;26:301–12. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan X, Curtin J, Xiong Y, et al. Isolation of cancer stem cells from adult glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene. 2004;23:9392–400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu G, Akasaki Y, Khong HT, et al. Cytotoxic T cell targeting of TRP-2 sensitizes human malignant glioma to chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2005;24:5226–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liau LM, Prins RM, Kiertscher SM, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination in glioblastoma patients induces systemic and intracranial T-cell responses modulated by the local central nervous system tumor microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5515–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilboa E. DC-based cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1195–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI31205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Q, Yuan X, Liu G, et al. Hedgehog Signaling Regulates Brain Tumor Initiating Cell Proliferation and Portends Shorter Survival for Patients with PTEN-Coexpressing Glioblastomas. Stem Cells. 2008 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spisek R, Kukreja A, Chen LC, et al. Frequent and specific immunity to the embryonal stem cell-associated antigen SOX2 in patients with monoclonal gammopathy. J Exp Med. 2007;204:831–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Hernandez Mde L, Gray A, Hubby B, et al. Prostate stem cell antigen vaccination induces a long-term protective immune response against prostate cancer in the absence of autoimmunity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:861–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pellegatta S, Poliani PL, Corno D, et al. Neurospheres enriched in cancer stem-like cells are highly effective in eliciting a dendritic cell-mediated immune response against malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10247–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu G, Yu JS, Zeng G, et al. AIM-2: a novel tumor antigen is expressed and presented by human glioma cells. J Immunother. 2004;27:220–6. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu G, Ying H, Zeng G, et al. HER-2, gp100, and MAGE-1 are expressed in human glioblastoma and recognized by cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4980–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu A, Wiesner S, Xiao J, et al. Expression of MHC I and NK ligands on human CD133+ glioma cells: possible targets of immunotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2007;83:121–31. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghods AJ, Irvin D, Liu G, et al. Spheres isolated from 9L gliosarcoma rat cell line possess chemoresistant and aggressive cancer stem-like cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1645–53. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzo G. Cancer genesis: stem tumour cells as an MHC-null/HSP70 - very high ‘primordial self’ escaping both MHC-restricted and MHC-non- restricted immunesurveillance. Med Hypotheses. 2001;56:724–30. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odeberg J, Piao JH, Samuelsson EB, et al. Low immunogenicity of in vitro-expanded human neural cells despite high MHC expression. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;161:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heisel SM, Ketter R, Keller A, et al. Increased seroreactivity to glioma-expressed antigen 2 in brain tumor patients under radiation. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada H, Lieberman FS, Walter KA, et al. Autologous glioma cell vaccine admixed with interleukin-4 gene transfected fibroblasts in the treatment of patients with malignant gliomas. J Transl Med. 2007;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.