Abstract

Introduction

Provisional stenting (PS) for simple coronary bifurcation lesions is the mainstay of treatment. A systematic two-stent approach is widely used for complex bifurcation lesions (CBLs). However, a randomised comparison of PS and two-stent techniques for CBLs has never been studied. Accordingly, the present study is designed to elucidate the benefits of two-stent treatment over PS in patients with CBLs.

Methods and analysis

This DEFINITION II study is a prospective, multinational, randomised, endpoint-driven trial to compare the benefits of the two-stent technique with PS for CBLs. A total of 660 patients with CBLs will be randomised in a 1:1 fashion to receive either PS or the two-stent technique. The primary endpoint is the rate of 12-month target lesion failure defined as the composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (MI) and clinically driven target lesion revascularisation. The major secondary endpoints include all causes of death, MI, target vessel revascularisation, in-stent restenosis, stroke and each individual component of the primary endpoints. The safety endpoint is the occurrence of definite or probable stent thrombosis.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol and informed consent have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing First Hospital, and accepted by each participating centre. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients. Findings of the study will be published in a peer-reviewed journal and disseminated at conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT02284750; Pre-results.

Keywords: coronary bifurcation lesions, systematic two-stent techniques, provisional stenting technique

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first prospective, multinational, randomised, endpoint-driven trial to compare the systematic two-stent and provisional stenting (PS) techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions (CBLs).

This study is built on the DEFINITION registry, which for the first time introduced an anatomical differentiation of coronary bifurcation lesion complexity and reported that PS for CBLs was associated with an increment of cardiac death compared with simple bifurcation lesions.

Selection of primary and secondary endpoints is in accordance with current practice in other cardiovascular clinical trials.

All participating sites are well versed in two-stent techniques (including double-kissing crush and culotte), which may not be reflective of clinical practice in smaller hospitals.

Background

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for bifurcation lesions is technically demanding and has a poor outcome at follow-up, as reflected by more frequent occurrences of in-stent restenosis (most localise at the ostium of the daughter branch) and more requirements for revascularisation. For a great majority of coronary bifurcation lesions, particularly when a small (diameter <2.0 mm) side branch (SB) with a focal (usually <5 mm in length) lesion is involved, provisional stenting (PS) is considered as the default approach.1–6 However, the efficacy of PS for a larger (≥2.5 mm in diameter) SB with a longer lesion (>5 mm in length) is under-reported.7 8 Furthermore, there is a lack of angiographic criteria for differentiating simple from complex bifurcation lesions (CBLs). In this regard, the DEFINITION registry study9 introduced for the first time an anatomical differentiation of bifurcation lesion complexity, which consisted of two major and six minor criteria. Based on the DEFINITION criteria, CBLs is defined as one major plus any two minor criteria. Investigators further reported that PS for CBLs was associated with an increment in cardiac death and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) compared with simple bifurcation lesions. Unfortunately, PS has not been compared with systematic two-stent techniques in a randomised fashion for patients with CBLs. Therefore, we design this prospective, multicentre, randomised (DEFINITION II) study to investigate the superiority of systematic two-stent approaches for PS treatment for patients with CBLs, as classified by the DEFINITION registry.

Methods and analysis

Study hypothesis

This study is designed to test the hypothesis that the application of systematic two-stent techniques will lead to a lower rate of target lesion failure (TLF), including cardiac death, target-vessel myocardial infarction (MI), or clinically driven target lesion revascularisation (TLR), compared with the PS technique, in patients with CBLs at 12 months after the indexed PCI procedure. CBLs are defined according to the DEFINITION study,9 and the criteria are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria of complex bifurcation lesions

| Criteria | Lesion characteristics |

| Major 1 | Distal LM bifurcation: SB-DS ≥70% and SB lesion length ≥10 mm |

| Major 2 | Non-LM bifurcation: SB-DS ≥90% and SB lesion length ≥10 mm |

| Minor 1 | Moderate to severe calcification |

| Minor 2 | Multiple lesions |

| Minor 3 | Bifurcation angle <45° or >70° |

| Minor 4 | Main vessel RVD <2.5 mm |

| Minor 5 | Thrombus-containing lesions |

| Minor 6 | MV lesion length ≥25 mm |

| Major 1+any 2 minor 1–6=complex bifurcation lesion | |

| Major 2+any 2 minor 1–6=complex bifurcation lesion | |

DS, diameter stenosis; LM, left main; MV, main vessel; RVD, reference vessel diameter; SB, side branch.

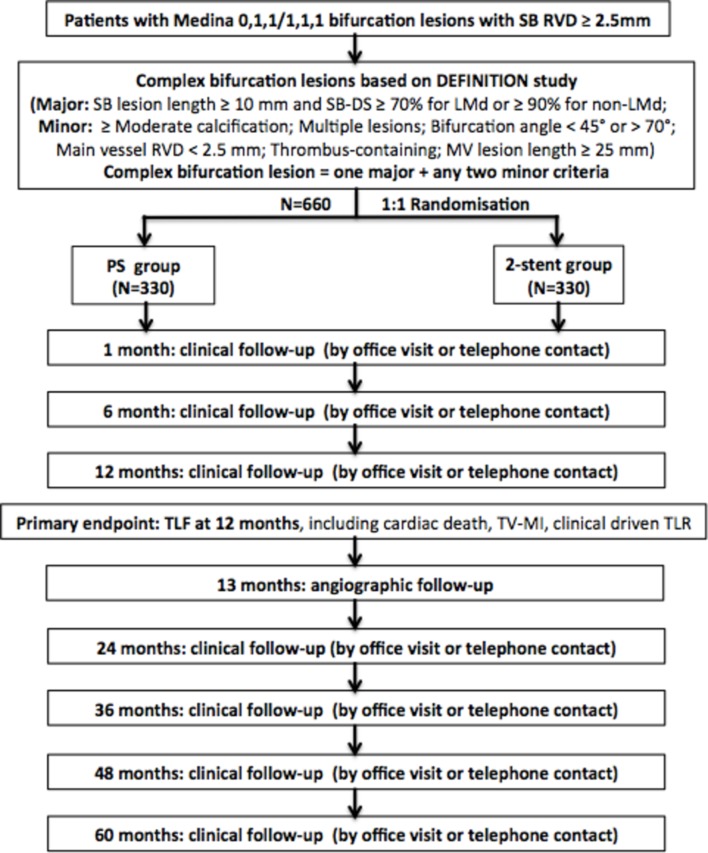

Study design

This is a prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled, superiority clinical trial at 45 sites worldwide (see online supplementary appendix) to enrol 660 patients with CBLs. The overall study flowchart is presented in figure 1. This study has been registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02284750), according to the statement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study design. DS, diameter stenosis; LMd, left main distal bifurcation; MV, main vessel; PS, provisional stenting; RVD, reference vessel diameter; SB, side branch; TLF, target lesion failure; TLR, target lesion revascularisation; TV-MI, target-vessel myocardial infarction.

bmjopen-2017-020019supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Study population and randomisation

The 660 patients scheduled for elective PCI with CBLs suitable for drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation are openly randomised 1:1 to either the systematic two-stent or the PS technique. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for the present study are listed in box 1. The planned enrolment duration is between December 2015 and December 2018, and the enrolment period may be extended if necessary. There are 446 patients enrolled up to September 2017.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Provision of informed consent prior to any study-specific procedures.

Men and women 18 years and older.

Established indication for percutaneous coronary intervention according to the guidelines of the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

Native coronary lesion suitable for drug-eluting stent placement.

True bifurcation lesions (Medina 0,1,1/1,1,1).

Reference vessel diameter in side branch ≥2.5 mm by visual estimation.

Complex bifurcation lesions based on DEFINITION study.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnancy or breastfeeding mother.

Comorbidity with an estimated life expectancy of <50% at 12 months.

Scheduled major surgery in the next 12 months.

Inability to follow the protocol and comply with follow-up requirements or any other reason that the investigator feels would place the patient at increased risk.

Previous enrolment in this study or treatment with an investigational drug or device under another study protocol in the past 30 days.

Known allergy to ticagrelor, clopidogrel or aspirin.

History of major haemorrhage (intracranial, gastrointestinal, etc).

Chronic total occlusion lesion in either left anterior descending artery or left circumflex artery or right coronary artery not recanalised.

Severe calcification needing rotational atherectomy.

Patient with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (within 24 hours from the onset of chest pain to admission).

A randomisation serial number for patients will be created by the Interactive Web Randomisation System. The randomisation serial number for each participating centre will be generated by the same system.

Study intervention and medication

Patients allocated to the two-stent group will receive the double-kissing (DK) crush or the culotte technique.

DK crush technique

The DK crush stenting technique has been described in detail elsewhere.7 10–12 Briefly, a stent with a stent/artery ratio of 1.1:1 is advanced into an SB. Another balloon with balloon/artery ratio of 1:1 is positioned in the main vessel (MV). Inflating the SB stent with a 2–3 mm protrusion into the MV, the stent balloon and SB wire are removed after confirming that there is no dissection in the distal SB by angiogram. Inflating the previous balloon in the MV performs the first crush. First, the kissing balloon inflation is performed after rewiring the SB from the proximal stent cell. An MV stent with a stent/artery ratio of 1.1:1 is inflated and crushes the SB stent again, which is then followed by rewiring the SB and the final kissing balloon inflation (FKBI). A proximal optimisation technique (POT) should be performed before and after FKBI. Postdilatation with a non-complaint balloon is recommended for all stents, with a suggested inflation pressure >18 atm.

Culotte technique

Culotte stenting has been described in detail elsewhere.13 In brief, the MV and SB are both wired. The SB is then stented first with a wire jailed in the MV. The MV is rewired through the stent struts (through a distal stent strut where possible), following balloon dilation and MV stenting. Then, second, rewiring the SB from a distal access is undertaken. A mandatory attempted FKBI is performed. Postdilatations with a non-complaint balloon are undertaken to optimise stent expansion. POT in the stented segment proximal to the bifurcation is recommended.

PS technique

PS is defined as a stent implantation in the MV with the jailed wire or jailed balloon protecting the SB,14 15 followed by kissing balloon dilatation if there is at least one of the following: >type B dissection and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow <3 at the ostial SB.5 An additional stent is required for the SB if any of the following issues are observed after kissing balloon inflation: >type B dissection or TIMI flow <3. POT is also recommended after MV stenting.

Intracoronary imaging

Intracoronary imaging tools, such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or optical coherence tomography, are at the discretion of the operators.

Study stents

Stents for all implanted lesions are DESs, including Firebird-2, or Firehawk (Microport, Shanghai, China), EXCEL (Jiwei, Shandong, China), BuMA stent (Sino Medical, Tianjin, China), Partner or Nano (Lepu Med, Beijing, China), Xience or Xience Prime (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, California, USA) and Endeavour Resolute or Endeavour Integrity (Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA).

Medication

All patients in the trial are treated with dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 year, according to contemporary guidelines and local practice. A loading dose of aspirin (300 mg) and clopidogrel (300 mg) or ticagrelor (180 mg) is recommended at least 6 hours before the PCI procedure. Heparin or an alternative antithrombotic agent (such as bivalirudin) must be used during the procedure to maintain an activated clotting time >280 s. After the PCI, a lifelong dosage of aspirin at 100 mg/day will be prescribed. The duration of clopidogrel treatment with 75 mg/day (or ticagrelor with 90 mg two times per day) is at least 12 months.

Biomarker assessment

Total creatine kinase (CK), CK-myocardial band isoenzyme (MB) and troponin T/I are dynamically measured before the procedure and until 72 hours postprocedure.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint in the present trial is TLF at 12 months after the indexed procedure, as defined by the composite of cardiac death, target vessel MI and clinically driven TLR. The major secondary endpoints include all causes of death, MI, target vessel revascularisation (TVR), in-stent restenosis, stroke and each individual component of the primary endpoints. The safety endpoint is the risk of Academic Research Consortium-defined stent thrombosis. Other endpoints are listed in box 2. Detailed definitions of the study endpoints are described in the online supplementary material.

Box 2. Study endpoints.

Primary endpoint

Target lesion failure: composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (MI), and target lesion revascularisation (TLR) at 12 months.

Secondary endpoints

All-cause death: cardiac death, non-cardiac death.

MI: periprocedural MI, spontaneous MI.

Revascularisation: TLR, target vessel revascularisation (TVR).

Stroke: ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke.

Combined endpoint of all-cause death, MI, TVR.

In-stent restenosis.

Other outcome parameters: New York Heart Association functional class, Braunwald class, net gain of lumen diameter, contrast volume, procedural time, devices consumed during indexed procedure, X-ray exposure time, X-ray dose.

Safety endpoints

Stent thrombosis.

Bleeding complications.

All endpoints are site reported in an electronic web-based capture system with the additional submission of supporting medical documents. All clinical events are assessed by an independent committee that was blinded to the study.

Follow-up

After hospital discharge, clinical follow-up is performed with visits (preferred) or telephone contact at 1, 6 and 12 months. Follow-up will be continued annually until 5 years after the index procedure. An angiographic follow-up will be encouraged for all patients, and it will be conducted 13 months after the index procedure, unless clinically indicated earlier. An independent committee that is blinded to the study assesses all clinical events.

Angiographic analysis

Quantitative coronary angiographic (QCA) analysis at baseline, postprocedure and follow-up is performed by the QCA laboratories at the Nanjing Heart Centre. The images are analysed by two experienced technicians who are blinded to the study design, with an interobserver and intraobserver variability under 5% (Kappa test).

Basic angiograms for all lesions should consist of at least injections after intracoronary injection of 100–200 µg of nitroglycerin. A bifurcation view must be gained for all patients; there should be an angulation difference between the two baseline angiograms of at least 30°. The diagnostic/guiding catheter should be well visible, near the centre of the angiogram and filled with dye. The index lesions should be well visible, near the centre of the angiogram and shown without foreshortening. Between the preangiogram and postangiogram, all balloon inflations and stent implantations should be documented by short cine runs.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be performed on the intent-to-treat population, defined as all patients randomised, regardless of the treatment actually received. The primary variable is time from randomisation to first occurrence of any event from the TLF. From previous studies, we hypothesised that the rate of a 1-year TLF would be 15% in the systematic two-stent technique group and 25% in the PS group. Accordingly, a total sample size of 600 is needed to detect a power of 0.8 (type II error=0.2, =0.05, two-tailed). Because of the considerable uncertainty, the enrolment is extended to 660 patients (10% increment).

The distribution of continuous variables will be assessed by the Kolmogrov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies or percentages and compared by x² statistics or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are summarised as the means±SD or median and compared using Student’s t-test (for normal data) and Mann-Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed variables). Survival curves with time-to-event data are generated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Comparisons between the two groups will be performed using the Cox proportional hazard model. A P value <0.05 is considered statistically significant. All analyses are performed with the use of the statistical programme SPSS V.24.0.

The extensive subgroup analysis will be performed to evaluate variation of treatment effects, as well as a test of interaction with the treatment for each subgroup variable. The substudies of clinical factors include age (age >75 years old), sex, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, current smoking, acute coronary syndrome, cardiac dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction <40%) and renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2). In addition, the substudies of angiographic and procedural factors include an unprotected distal left main (LM) bifurcation lesion, the use of IVUS and complete revascularisation. Therefore, there are a total of 12 prespecified subgroup analyses to explore the consistency of effects on two-stent techniques for CBLs.

Ethics and dissemination

The study is performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practices. The study protocol and informed consent have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing First Hospital (KY20141128-01-KS-01, in the online supplementary material), and accepted by each participating centre. Written informed consent for participation in the trial was obtained from all enrolled patients. Dissemination of the results will include conference presentations and publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial organisation

The trial was designed by the principal investigator and the executive committee. The executive committee members are also responsible for reporting the results and drafting the manuscripts. The executive committee, together with the steering committee, the data and safety monitoring committee and the independent endpoints adjudication committee are involved in the present trial.

All centres with experience in two-stent techniques (including DK crush and culotte) can participate in the study. Details about trial organisation are listed in the online supplementary material.

Discussion

Several randomised studies have demonstrated that the PS technique using a jailed wire in the SB is the gold standard treatment for the majority of bifurcation lesions;1–6 however, the bifurcation lesions enrolled in these studies were not all true bifurcation lesions. They were either moderate narrow or focused lesions at the SB ostium. The DKCRUSH II trial7 demonstrated that the two-stent technique using a DK crush was associated with a lower rate of TVR in true coronary bifurcation lesions with an SB lesion length of 15 mm, compared with PS. A meta-analysis also showed that the two-stent technique remained an optional treatment for true bifurcation lesions with a large SB.16 In addition, the consensus of the European Bifurcation Club17 was that true bifurcations with a large SB and ostial disease extending more than 5 mm from the carina are likely to require two-stent techniques. Therefore, a novel bifurcation classification is needed to identify which bifurcation lesions should be treated with two-stent techniques instead of PS.

A practical and easy-to-use classification was proposed in the DEFINITION registry by Shao-Liang Chen,9 which included two major criteria and six minor criteria. According to the newly established criteria, 70% exhibited simple bifurcation lesions, and the remaining 30% were classified as CBLs in 3660 patients with true coronary bifurcation lesions (Medina 1,1,1 and 0,1,1) and an SB diameter ≥2.5 mm by visual estimation. As was expected, the two-stent technique did not show any benefits over PS for the simple bifurcation lesions. However, for CBLs, two-stent techniques were associated with less in-hospital mortality and 1 year MACE than PS. This important finding will be further verified in the randomised DEFINITION II trial.

LM bifurcation lesions are unique bifurcation lesions. The diameter of the SB is bigger, and the bifurcation angle is also larger compared with that of a non-LM bifurcation. Culotte stenting with bare metal stents has been largely abandoned because of high restenosis rates. Since the introduction of DESs, culotte stenting has regained its popularity. Murasato reported restriction of the stent expansion such as a ‘napkin ring’ in culotte stenting, using closed-cell design stents.18 In our bench study, even using open-cell design stents in T type bifurcations, significant stent under expansion was revealed in culotte stenting, in contrast to DK crush.19 The DKCRUSH III trial confirmed that DK crush was associated with a lower TLR and stent thrombosis for LM bifurcation, compared with culotte stenting at 3-year follow-up.10 20 Considering the shortages of culotte stenting, we strongly recommend the use of culotte stenting in non-LM bifurcation instead of LM bifurcations. PS with a jailed balloon is a safer alternative than a jailed wire to protect the SB, especially for a high risk of SB occlusion after MV stenting.14 15 Given that CBLs will be enrolled in the study if a patient is randomised into the PS group, either the use of a jailed balloon or a jailed wire will be allowed at the discretion of the operators.

Conclusions

Strategies for coronary bifurcation lesions should be individualised. PS is the default approach for simple bifurcation lesions. The DEFINITION II study is investigating whether systematic two-stent technique will be superior to PS in CBLs, regarding the incidence of TLF at 12 months.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of Ling Lin, Hai-Mei Xu and Ying-Ying Zhao to data collection. They also acknowledge Bao-Xiang Duan, Lin Lin, Ji Yong and Linda Lison for their contribution in the data and safety monitoring.

Footnotes

J-JZ and X-FG contributed equally.

Contributors: S-LC made substantial contributions to study conception and design, and to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. J-JZ and X-FG wrote the first draft. Y-LH, JK, LT and ZG provided data management and statistical expertise. DT, SL, L-KM, FL, SY, JZ, MM, LL, R-YZ, H-SZ, TS, PX, Z-NJ, LH, W-HY, X-SQ, Q-HL, LH, CP, YW, L-JL, LZ, X-MW, S-YW, Q-HL, J-QY, L-LC, FL, AER, L-MZ, S-QD, KV, Y-SZ, M-YY, CC, IS, Y-X, Y-LT, Z-LS, QJ, Y-HZ, XW, FY, N-LT, SL, and Z-ZL provided comments and suggestions in critical revision of the article. All authors approved the final version of the article.

Funding: The present trial was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81270191, NSFC 91439118) and Health and Family Planning Commission Foundation of Nanjing (YKK16124).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol and informed consent have been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing First Hospital (KY20141128-01-KS-01) and accepted by each participating center. Version of this protocol was 1.2 and was approved on 9 March 2016 (in the supplemental material).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Colombo A, Bramucci E, Saccà S, et al. . Randomized study of the crush technique versus provisional side-branch stenting in true coronary bifurcations: the CACTUS (Coronary Bifurcations: Application of the Crushing Technique Using Sirolimus-Eluting Stents) Study. Circulation 2009;119:71–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferenc M, Gick M, Kienzle RP, et al. . Randomized trial on routine vs. provisional T-stenting in the treatment of de novo coronary bifurcation lesions. Eur Heart J 2008;29:2859–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hildick-Smith D, de Belder AJ, Cooter N, et al. . Randomized trial of simple versus complex drug-eluting stenting for bifurcation lesions: the British Bifurcation Coronary Study: old, new, and evolving strategies. Circulation 2010;121:1235–43. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.888297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pan M, de Lezo JS, Medina A, et al. . Rapamycin-eluting stents for the treatment of bifurcated coronary lesions: a randomized comparison of a simple versus complex strategy. Am Heart J 2004;148:857–64. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steigen TK, Maeng M, Wiseth R, et al. . Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation 2006;114:1955–61. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombo A, Moses JW, Morice MC, et al. . Randomized study to evaluate sirolimus-eluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation 2004;109:1244–9. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118474.71662.E3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL, Santoso T, Zhang JJ, et al. . A randomized clinical study comparing double kissing crush with provisional stenting for treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: results from the DKCRUSH-II (Double Kissing Crush versus Provisional Stenting Technique for Treatment of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:914–20. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin QF, Luo YK, Lin CG, et al. . Choice of stenting strategy in true coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Coron Artery Dis 2010;21:345–51. 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32833ce04c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SL, Sheiban I, Xu B, et al. . Impact of the complexity of bifurcation lesions treated with drug-eluting stents: the DEFINITION study (Definitions and impact of complEx biFurcation lesIons on clinical outcomes after percutaNeous coronary IntervenTIOn using drug-eluting steNts). JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2014;7:1266–76. 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, et al. . Comparison of double kissing crush versus Culotte stenting for unprotected distal left main bifurcation lesions: results from a multicenter, randomized, prospective DKCRUSH-III study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1482–8. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SL, Ye F, Zhang JJ, et al. . [DK crush technique: modified treatment of bifurcation lesions in coronary artery]. Chin Med J 2005;118:1746–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen SL, Zhang JJ, Ye F, et al. . Study comparing the double kissing (DK) crush with classical crush for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions: the DKCRUSH-1 Bifurcation Study with drug-eluting stents. Eur J Clin Invest 2008;38:361–71. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01949.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chevalier B, Glatt B, Royer T, et al. . Placement of coronary stents in bifurcation lesions by the “culotte” technique. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:943–9. 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00510-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Depta JP, Patel Y, Patel JS, et al. . Long-term clinical outcomes with the use of a modified provisional jailed-balloon stenting technique for the treatment of nonleft main coronary bifurcation lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013;82:E637–E646. 10.1002/ccd.24778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh J, Patel Y, Depta JP, et al. . A modified provisional stenting approach to coronary bifurcation lesions: clinical application of the “jailed-balloon technique”. J Interv Cardiol 2012;25:289–96. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2011.00716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao XF, Zhang YJ, Tian NL, et al. . Stenting strategy for coronary artery bifurcation with drug-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of nine randomised trials and systematic review. EuroIntervention 2014;10:561–9. 10.4244/EIJY14M06_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stankovic G, Lefèvre T, Chieffo A, et al. . Consensus from the 7th European bifurcation club meeting. EuroIntervention 2013;9:36–45. 10.4244/EIJV9I1A7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murasato Y, Hikichi Y, Horiuchi M. Examination of stent deformation and gap formation after complex stenting of left main coronary artery bifurcations using microfocus computed tomography. J Interv Cardiol 2009;22:135–44. 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2009.00436.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rab T, Sheiban I, Louvard Y, et al. . Current interventions for the left main bifurcation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2017;10:849–65. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen SL, Xu B, Han YL, et al. . Clinical outcome after DK crush versus culotte stenting of distal left main bifurcation lesions: the 3-year follow-up results of the DKCRUSH-III Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:1335–42. 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020019supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)