Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the district health management fellowship training programme in the north-west of Iran.

Data sources/study setting

The programme was introduced to build the managerial capacity of district health managers in Iran. Eighty-nine heads of units in the province’s health centre, district health managers and the health deputies of the district health centres in the north-west provinces of Iran had registered for the district health management fellowship training programme in Tabriz in 2015–2016.

Study design

This was an educational evaluation study to evaluate training courses to measure participants' reactions and learning and, to a lesser extent, application of training to their job and the organisational impact.

Data collection/extraction methods

Valid and reliable questionnaires were used to assess learning techniques and views towards the fellowship, and self-assessment of health managers’ knowledge and skills. Also, pretest and post-test examinations were conducted in each course and a portfolio was provided to the trainees to be completed in their work settings.

Principal findings

About 63% of the participants were medical doctors and 42.3% of them had over 20 years of experience. Learning by practice (scored 18.37 out of 20) and access to publications (17.27) were the most useful methods of training in health planning and management from the participants’ perspective. Moreover, meeting peers from other districts and the academic credibility of teachers were the most important features of the current programme. Based on the managers’ self-assessment, they were most skilful in quality improvement, managing, planning and evaluation of the district. The results of the post-test analysis on data collected from district health managers showed the highest scores in managing the district (77 out of 100) and planning and evaluation (69) of the courses.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that training courses, methods and improvement in managers' knowledge about the health system and the skills necessary to manage their organisation were acceptable.

Keywords: district health system, district health manager, training program evaluation, Iran

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use if short-term and more subjective measures, pre-test and post-test rather than the real impact of the programme is a limitation.

The high managerial turnover rate makes it impossible to follow-up the impact of the programme.

We did not analyse the role of other factors and confounders.

The programme developed was used by the Ministry of Health as an applicable package for training district health managers across the country.

The training content was considered as applicable, useful and relevant to real work settings.

Introduction

A health system is an arrangement of the organisational structure, physical resources and staff to improve the health status of a particular population. In the last decades, strengthening the health system and its infrastructure has become as one of the priorities in progressive health systems, especially in developing countries.1

Strengthening of the leadership and management in a health system is one of the most challenging issues that need to be measured and there are few empirical studies of its impact on service delivery and health outcomes.2 3 In addition, the existing literature in developing countries indicates shortfalls in managerial capabilities and training programmes. For example, Muchekeza et al conducted a study in Zimbabwe and concluded that almost half of the district health managers do not list the tasks of district health executives and some of them had insufficient managerial skills and training.4 Also, financing, health policy and health management were perceived to be the most essential requirements of management training in Kenya, Nigeria and Senegal.5 Bonenberger et al demonstrated that data management, attending workshops, travelling, financial management, training of staff, and drugs and supply management were the highest time-consuming tasks of district health managers in Ghana.6 Furthermore, Asante et al recognised that lack of skills in financing and human resource management among provincial health departments in the Solomon Islands was the main concern while management support systems were not able to support managers.7

Filerman indicated that the core competencies of health management were human resources management, general management skills and the skills of the top management.8 Team-based job training is an effective strategy to improve the effectiveness of management training programmes.8 The interventions designed to strengthen leadership and management must lay emphasis on changes in health and service delivery outcomes. However, due to complications in investigating the relationship between managers’ empowerment programme with health provision and health status, many researchers have concentrated on managers’ knowledge and skills.3 9 According to De Brouwere’s and Van Balen’s study, most of the trainees applied the skills and knowledge gained from a 12-week training course. Also, team-based district health management, and use of updated and participatory approaches in the training programme could be attributed to the success of the training course.10

In Iran, the district health managers of district rural health facilities, district hospitals, health centres, and health posts. Each of these facilities is involved in providing specific health services. District hospitals deliver inpatient and outpatient services. Health centres concentrate on ambulatory and preventive services. Health posts are supposed to be the first line of exposure for patients, providing a large range of preventive and primary services. Also, the provincial health centre department directs district health centres. Like many developing countries, general physicians are appointed as health managers of district and subdistrict centres without any formal or hands-on training.11 12

The focus of the newly proposed reforms in the health system, that is supported by the World Bank, is on market mechanisms, effectiveness and efficiency.13 Because of the managers' capabilities and their influences, especially in the first line, management is one of the key determinants of health system effectiveness.8 For instance, Conn et al found that strengthening the health management programme in Gambia led to some improvements in district-level health services especially in team planning and coordination, and management of the available but limited resources.14 Besides, Pfeffermann determined that strengthening the health management programmes was the most cost-effective intervention.15

This study aimed to evaluate the district health management fellowship training programme using Kirkpatrick’s four-level model (reaction, learning, application and impact)16 in the north-west of Iran. The programme was designed to build managerial capability in Iranian district health managers.

Materials and methods

Design and setting

This study, based on Kirkpatrick’s framework, was an evaluation of training programmes to measure participants' reactions, learning and, to a lesser extent, application of training in their careers, on the basis of the respondents' perception to apply the lessons and the organisational impact. It was conducted between June 2015 and February 2016 in Tabriz.

Participants and the training programme

Following assessment of the the educational needs proposed by the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education, a training programme was developed and introduced for district health system managers in the National Public Health Management Centre (NPMC) of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, in order to improve their skills and knowledge on health system management.17 Eighty-nine health managers registered for this training programme. Two cohorts of 89 health officials (44 and 45 participants in each cohort) were selected by the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education to participate in the courses (table 1). Our target population was all heads of provincial health centres, district health managers and health deputies of district health centres in the north-west provinces of Iran.

Table 1.

Training courses of district management training fellowships

| Educational courses | Summary of content | Location* | Date (duration) |

| Management, leadership | Basic concepts of management, leadership and supervision, change management, team management, conflict management, basic skills in communication, staff motivation | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | June 2015 (2 days) |

| Managing the district | Introduction to health and health systems, PHC approach in the organisation and management of health services, district health systems, disaster preparedness, development plans | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | June 2015 (2 days) |

| Quality improvement | Quality management in health systems, quality improvement approaches, quality improvement methods, focus PDCA, clinical audit, process mapping | MUMS, Maragheh, Iran | August 2015 (3 days) |

| Planning and evaluation | Situation analysis of district health, strategic planning, operational planning, evaluation methods and accreditation, priority setting, project planning methods | AUMS, Ardabil, Iran | September 2015 (3 days) |

| Health information management | Health management information systems, health indicators, health data analysis | ZUMS, Zanjan, Iran | October 2015 (2 days) |

| Health resources management and economics | Accrual accounting, financial control, payment mechanisms, health economy, management of physical infrastructure, health insurance, cost calculation and budgeting | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | November 2015 (3 days) |

| Community participation | Health need assessment in the district, health education techniques, community participation methods, multisectoral collaboration and advocacy, social marketing, techniques and methods for public participation | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | November 2015 (2 days) |

| Epidemiology | Introduction to epidemiology, epidemiological assessment of the health situation in a district | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | December 2015 (2 days) |

| Research in health systems | Quantitative and qualitative research in health systems, data management, data analysis | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | January 2016 (3 days) |

| Human resources and organisational creativity | Human resources management, employee training and empowering, effective communication, time management, creativity and innovation | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | February 2016 (1 day) |

| Rules and ethics | Management ethics, legal issues in management, external inspection and accounting | NPMC Tabriz, Iran | February 2016 (1 day) |

*National Public Health Management Centre (NPMC), Maraghe University of Medical Sciences (MUMS), Ardabil University of Medical Sciences (AUMS), Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (ZUMS).

PDCA, plan, do, check, act; PHC, primary health care.

Data collection and instrument

A valid and reliable questionnaire was used to collect data from participants. We used a questionnaire that was designed in the University of Leeds and had previously been adapted and tested by the NPMC staff and was used as an applicable tool to elucidate management training courses in NPMC.18 The questionnaire contained four sections: (1) questions about demographic characteristics of respondents, (2) previous training experiences, the importance of the current training programme and satisfaction from different learning methods in health planning and management among district heath managers, (3) health managers’ perceptions about usefulness and applicability of training programmes (4) self-assessment of health managers’ knowledge, skills and relevance to their job and future training topics. Totally, 72 of the 89 training participants (response rate=81%) filled up and returned the questionnaire (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographics of participants in rating educational assessment

| Variable | Number | % |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 61 | 84.7 |

| Female | 11 | 15.3 |

| Age, years | ||

| <40 | 17 | 25 |

| 40–50 | 43 | 61.5 |

| >50 | 9 | 13.5 |

| Education | ||

| BSc | 14 | 19.4 |

| MSc | 8 | 11.1 |

| MD | 46 | 63.9 |

| PhD | 4 | 5.6 |

| Job position | ||

| Head of unit | 20 | 27.8 |

| Head of district health deputy | 22 | 30.5 |

| District health manager | 30 | 41.7 |

| Years in current job | ||

| <5 | 4 | 5.6 |

| 5–10 | 6 | 8.3 |

| 10–15 | 12 | 16.7 |

| 15–20 | 24 | 33.3 |

| >20 | 26 | 36.1 |

The satisfaction on the different learning methods was rated based on a 4-point Likert Scale (very high, high, moderate, low) and the experiences of the different learning methods were dichotomous variables. Also, the importance of each method was rated on a 0–20 scale. These questionnaires were presented to participants at the beginning of the first course of the training programme.

For assessment of the usefulness and perception of the respondents to apply the lessons learnt from the training material used, the respondents were asked to indicate their agreement to 15 statements (due to negative meaning of some items, sometimes very high had a negative effect on score) on a 5-point Likert Scale. Finally, the results were presented on a 3-point scale as: agree, neutral and disagree.

Self-assessment of the health managers' knowledge and skills was rated on a 4-point scale, and relevance of the courses to their work and future training were rated on a 3-point scale and dichotomous yes or no answers.

Furthermore, pretest and post-test examinations in each course were conducted to evaluate the usefulness of courses in terms of contents. Pretests were performed at the beginning of each course. Simultaneously the post-test related to the previous course was performed. At the beginning of each course, the course directors developed an exam sheet based on the contents of the course. Also, to ensure reliability in assessment only matching, restricted response and multiple choice questions were prepared. A portfolio based on fellowship content was also provided to the trainees to be completed in their work settings.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided written, signed informed consent before enrolling for the study and filling up the questionnaire. Participants who were not interested in contributing or who did not continue the research process were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, SD and frequencies (%)) were used to point out the basic properties of variables for quantitative and categorical variables. Also, pretest and post-test examinations correcting based on standard response and then normalised as 0 to 100. For statistical relationship analysis the SPSS V.17 statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used.

Result

According to the findings, 84.7% of participants were male, 61.5% were between 40 years and 50 years of age, 41.7% were district health managers and 27.8% were heads of units in provincial health centres. About 63.9% of the participants were medical doctors. Only 5.6% of participants had worked 5 years or less in their current position and 36.1% of them had more than 20 years work experience (table 2).

Learning for health planning and management

Respondents were asked to choose from a range of 0–20 points on 13 learning methods, assigning higher points to the more important methods. Learning by practice (scored 18.37 out of 20), access to publications (17.27), and workshops, meetings and conferences (14.99) were chosen as the three most important methods (table 3).

Table 3.

Experiences, importance of and satisfaction with learning techniques on health planning, and management among district heath managers

| Learning method | Importance of learning techniques* | Having experience in learning methods† | Satisfaction with learning techniques Number (%) |

|||

| Mean (SD) | Number (%) | Very High | High | Moderate | Low | |

| Learning by practice | 18.37 (2.1) | 59 (81.9) | 29 (41.4) | 33 (47.1) | 8 (11.4) | |

| Working with experienced persons | 13.12 (4.9) | 53 (73.6) | 26 (37.7) | 37 (53.6) | 5 (7.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| Access to publications | 17.27 (2.7) | 49 (68.1) | 8 (12.5) | 33 (51.6) | 20 (31.3) | 3 (4.7) |

| Practice or being involved in research | 14.75 (3.7) | 33 (45.8) | 7 (12.5) | 18 (32.1) | 26 (46.4) | 5 (8.9) |

| On-line learning | 13.07 (4.6) | 28 (38.9) | 5 (9.4) | 17 (32.1) | 23 (43.4) | 8 (15.1) |

| Study tours | 15.53 (3.4) | 19 (26.4) | 9 (22.0) | 12 (29.3) | 8 (19.5) | 12 (29.3) |

| Formal certified training | 12.90 (5.3) | 47 (65.3) | 9 (15.0) | 29 (48.3) | 16 (26.7) | 6 (10.0) |

| Attending workshops, meetings and conferences | 14.99 (3.9) | 51 (70.8) | 16 (24.2) | 32 (48.5) | 17 (25.8) | 1 (1.5) |

| Working with colleagues who shared training | 10.72 (5.5) | 46 (63.9) | 17 (27.4) | 34 (54.8) | 9 (14.5) | 2 (3.2) |

| Discussions with colleagues | 12.72 (4.8) | 52 (72.2) | 19 (27.9) | 35 (51.5) | 13 (19.1) | 1 (1.5) |

| Networks | 12.68 (6.1) | 39 (54.2) | 8 (13.5) | 23 (39.0) | 23 (39.0) | 5 (8.5) |

| Twinning of organisations | 12.78 (4.7) | 35 (48.6) | 8 (13.8) | 20 (34.5) | 23 (39.7) | 7 (12.1) |

*The importance of each method was rated on a 0–20 scale.

†Number of participants who have declared having experience in that learning method.

Also, the trainees indicated that learning by practice (81.9%), working with experienced persons (73.6%), discussions with colleagues during workshops (72.2%), and meetings and conferences (70.8%) were the postexperience learning methods among health managers (table 3).

With regard to satisfaction level, respondents determined learning by practice, working with experienced persons, discussions with colleagues, working with colleagues who shared training and workshops, meetings and conferences, as the highest influential factors. Also, on-line learning and practice or being involved in research were reported as the most unsatisfactory methods to training planning and management (table 3).

Overall views on the training courses

Trainees agreed most strongly with the statements that ‘the strength of the course was to make an opportunity to meet up with peers from other districts to share experiences' and also ‘the instructors of the courses had academic credibility’. More than 78% were satisfied with the amount of time they had spent to attend the training course and more than 76% mentioned that the mix of theory and practice during the training period was acceptable and that the course had dramatically changed their thoughts. Of the respondents 34% posited that the course was interesting. More than 60% of respondents disagreed with the opinion that there was too much emphasis on theory in the courses and their boss did not value these courses (table 4).

Table 4.

Health manager views towards the district management training fellowship courses

| Statement | Attitude | ||

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| The strength of this course is that it gave me the chance to meet my peers from other districts. | 48 (80) | 9 (15) | 3 (5) |

| The course made me realise the importance of continuous learning. | 43 (71.6) | 12 (20.0) | 5 (8.4) |

| The teachers of the courses had academic credibility. | 48 (80) | 12 (20.0) | |

| The course was interesting. | 45 (75.0) | 13 (21.6) | 2 (3.3) |

| The course was relevant to the work I am required to do. | 44 (73.3) | 12 (20.0) | 4 (6.7) |

| The course changed my way of thinking. | 46 (76.7) | 11 (18.3) | 3 (5) |

| The courses provided a linkage between training of individuals and institutional strengthening, so that both reinforce each other. | 42 (70.0) | 12 (20.0) | 5 (8.3) |

| There should be more in-country courses of this nature. | 37 (61.7) | 14 (23.3) | 9 (15) |

| The course will help my career. | 41 (68.3) | 15 (25.0) | 4 (6.7) |

| The course was worth the time it took. | 47 (78.3) | 9 (15) | 4 (6.7) |

| The course changed my ways of practice. | 42 (70.0) | 13 (21.6) | 5 (8.3) |

| There was an acceptable blend of theory and practice in the course. | 46 (76.7) | 11 (18.3) | 3 (5) |

| There was too much emphasis on theory. | 14 (23.3) | 8 (46.7) | 38 (63.3) |

| My boss did not value this course. | 14 (23.3) | 9 (28.3) | 37 (61.7) |

| The course was too demanding. | 37 (61.7) | 13 (21.6) | 10 (16.7) |

Usefulness and respondents' perception on the application of the training lessons

Based on the findings, most specialised areas of knowledge met the health managers’ training needs including quality improvement, managing the district, planning and evaluation, epidemiology and advocacy, and community participation (table 5).

Table 5.

Self-assessment of health managers' knowledge and skills and respondents' perception to apply the training lessons in each of the fellowship courses

| Topic/subject | Level of skills and knowledge (%) |

Relevance to your work (%) | Relevance to your future training (%) | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Yes | No | |

| Managing the district | 6.9 | 36.2 | 41.4 | 15.5 | 21.4 | 78.6 | 92.5 | 7.5 | ||

| Quality improvement | 6.9 | 8.6 | 17.2 | 39.7 | 27.6 | 3.6 | 26.8 | 69.6 | 88.2 | 11.8 |

| Health information management | 5.3 | 8.8 | 38.6 | 35.1 | 12.3 | 3.6 | 34.5 | 61.8 | 94.0 | 6.0 |

| Epidemiology | 1.8 | 12.3 | 35.1 | 33.3 | 17.5 | 3.6 | 34.5 | 61.8 | 87.8 | 12.2 |

| Chronic disease management | 3.5 | 21.1 | 38.6 | 24.6 | 12.3 | 9.3 | 38.9 | 51.9 | 92.0 | 8.0 |

| Planning and evaluation | 12.7 | 32.7 | 32.7 | 21.8 | 1.9 | 31.5 | 66.7 | 91.8 | 8.2 | |

| Research in the health system | 5.3 | 14.0 | 33.3 | 26.3 | 21.1 | 10.9 | 34.5 | 54.5 | 85.7 | 14.3 |

| Advocacy and community participation | 1.7 | 15.5 | 36.2 | 25.9 | 20.7 | 5.4 | 37.5 | 57.1 | 88.0 | 12.0 |

| Accrual accounting | 27.3 | 32.7 | 16.4 | 14.5 | 9.1 | 25.0 | 44.2 | 30.8 | 63.8 | 36.2 |

| Health economics | 19.6 | 30.4 | 26.8 | 16.1 | 7.1 | 24.5 | 35.8 | 39.6 | 75.0 | 25.0 |

| Human resources and organisational creativity | 5.8 | 28.8 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 15.4 | 15.1 | 32.1 | 52.8 | 82.6 | 17.4 |

| Management, leadership | 1.8 | 25.5 | 29.1 | 29.1 | 14.5 | 5.7 | 26.4 | 67.9 | 95.8 | 4.2 |

| Rules and ethics | 10.9 | 27.3 | 23.6 | 23.6 | 14.5 | 11.3 | 34.0 | 54.7 | 89.1 | 10.9 |

‘1’—no knowledge/skills at all and ‘5’—comprehensive knowledge and sound practical skills.

Relevance of the particular topic to work on a scale of 1–3, where ‘1’—not relevant and ‘3’—completely relevant.

Likewise, participants emphasised that district management, quality improvement, basic management and leadership skills, planning and evaluation, health information management and epidemiology courses were most relevant to their career. On the other hand, accrual accounting and health economics were the least relevance courses (table 5).

Also, basic concepts of management and leadership, managing the district, health information management, planning and evaluation, and chronic disease management were the most relevant topics for their future training (table 5).

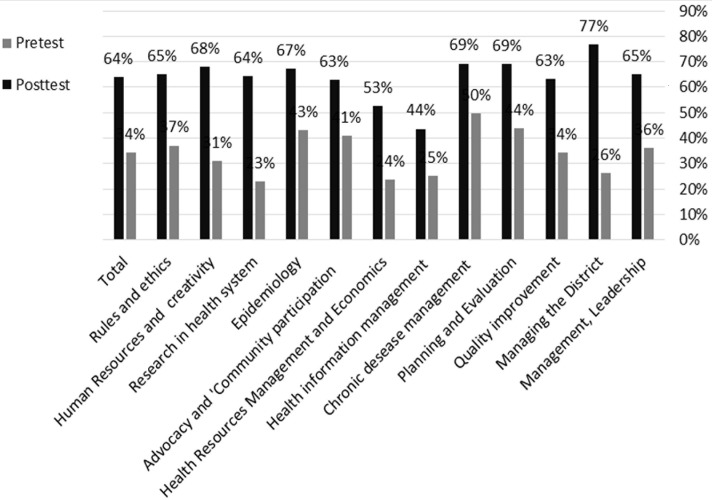

According to pretest and post-test results, after training, district health managers obtained the highest scores in managing the district (77 out of 100), planning and evaluation (69), chronic disease management (69), human resources and creativity (68), and epidemiology (67). Also, health information (44) and health resources management and health economics (53) gained the least score among health managers. Finally, the courses on managing the district (51%), research in the health system (42%), and human resources and creativity (37%) had the most positive differences between pretest and post-test scores (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pretest and post-test results of the district management training fellowships’ training courses.

Discussion

This study evaluated the district health management’s fellowship training programme in Tabriz based on Kirkpatrick’s four-level model. This study was a self-assessment evaluation and a pretest–post-test examination. The results of these analyses indicated that participants' reactions to the training programme were satisfactory and the courses have had a positive effect on attitude, knowledge and skills. Based on respondents' perception the majority of the trainees stated that they would be able to apply the new knowledge and skills to their job. Moreover, due to the positive impact of the training programme, the organisation and process of the district health system would be improved by trained and empowered managers.

We found that learning by practice, access to publications, workshops, and meetings and conferences were the most useful methods of learning. In addition, learning by practice and working with the experienced were the most satisfactory methods of learning. It is important to note that adult learners can effectively understand teaching content by identifying their training needs, active participation in training programmes and practice what they are learning in their field.19 20 However, some concerns should be noted in this regard. First, because the district health managers lack formal training in management,11 12 a formal structured management training in a health setting is essential.21 Second, the methods of developing management-related competencies in a real setting may vary given the management levels and different sectors.22–25 Third, improving the effectiveness of the management training programme and monitoring the specific system is the most useful way of providing continuous education services for health managers.

Also, based on the results, health managers’ satisfaction through on-line training was low. Beanland et al indicated that the use of novel communication technologies such as the internet is an effective training method in the health system.26 However, in our study, the low satisfaction with on-line training could be because of a weak on-line learning infrastructure and health system information technology, as well as the low skills of health managers in using these technologies.

According to the findings, meeting peers from other districts in order to share experiences and also academic credibility of the instructors were the most important features of district management training fellowships. Although, many management training programmes are mandatory and they are required by provincial and national authorities in most developing countries,19 making the content and structure of training programmes more attractive and useful is an effective strategy for encouraging attendance and increasing the quality of such programmes. For instance, De Brouwere et al found that the supervision, teamworking and problem-solving models are the key elements of successful training courses.27 Likewise, Marquez et al revealed that problem-solving training methods can increase the skills and abilities of managers and also produce a new generation of managers for organisations.28 However, it must be noted that the policy and practice of governments and donor organisations affect the effectiveness of management capabilities.14

Additionally, the results of the study indicated that after the training programme the participants, who were managers with little knowledge of most of the courses, were more skilful in quality improvement, managing the district, and planning and evaluation. In this regard, Muchekeza et al recognised that a lack of management ability of district health executives in Midlands province, Zimbabwe,4 and weakness in leadership and priority setting in Uganda were the most perceived shortfalls among district health managers.29 Also, leadership and governance,29 30 monitoring and evaluation, human resource management, strategic planning and general health services management,4 budgeting and finance,7 30 information management, procurement and supply,7 29 and community participation30 were the most required training topics in the different settings.

The results of our study point out that district health managers reached the highest post-test scores in courses of managing the district, planning and evaluation, chronic disease management, human resources, and creativity and epidemiology. Moreover, health information, health resources management and health economics needed more training courses using different teaching methods. We found that the syllabus and teaching methods in this training programme had high and positive effects on improving district health managers' knowledge of managing the district, research in the health system, and human resources and creativity based on the participants' self-assessment. Whereas these findings emerged based on participants' self-assessment and do not be tested in real setting and in the implementation phase, so it’s not possible to conclude its effectiveness definitively and practically, however, it can be used as an initial indicator of the effect of educational programme in the real setting. In this regard, Pal et al showed that district health planning, financial management, and technical and administrative issues were the most essential aspects of management training for Madhya Pradesh health managers.31 Another study by Conn et al showed that team planning, coordination and resource management were the aspects that could be improved by strengthening health management programmes.14 While, Diaz-Monsalve found that continuity of training for health managers and continuous management support were two critical factors for successful and effective education.32

Conclusion

The Tabriz health management fellowship training programme was developed based on the educational need assessment of the district health managers in the north-west of Iran and for training them; it was supported by the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical education as well as the health deputy of the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. The results of this study showed an acceptable rate of trainees’ satisfaction with the courses and the different teaching methods, and also showed an improvement in their knowledge of health system management. We found that the training contents were applicable, useful and relevant to real work settings. Last but not least, simultaneous and continuous supervision and support is highly beneficial for improving the effectiveness of any training course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eastern Azerbaijan province health center employees and district health managers for their contribution to data collection. This study was approved by Tabriz Health Services Management Research Center and School of Management and Medical Informatics, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Contributors: KG carried out proposal drafting, developed the study design, participated in data collection, performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript; JST carried out proposal drafting, participated in data collection and drafted the manuscript; MF participated in study design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript; SI participated in data collection, performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript; AG and HJ developed the study design, provided coordination and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the School of Management and Medical Informatics of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz Health Services Management Research Centre and Health Deputy of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Tabriz University of Medical Sciences Research & Ethics Committee (number: TBZMED.REC.1394.714) approved the design and procedure of this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

References

- 1.Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, et al. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000-10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet 2010;375:2032–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60678-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salas E, DiazGranados D, Klein C, et al. Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. Hum Factors 2008;50:903–33. 10.1518/001872008X375009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saleh SS, Williams D, Balougan M. Evaluating the effectiveness of public health leadership training: the NEPHLI experience. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1245–9. 10.2105/AJPH.94.7.1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muchekeza M, Chimusoro A, Gombe NT, et al. District health executives in Midlands province, Zimbabwe: are they performing as expected? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:335 10.1186/1472-6963-12-335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine J. Business schools and health care management training: a strategic perspective. Global Business School Network 2009:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonenberger M, Aikins M, Akweongo P, et al. What Do District Health Managers in Ghana Use Their Working Time for? A Case Study of Three Districts. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130633 10.1371/journal.pone.0130633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asante A, Roberts G, Hall J. A review of health leadership and management capacity in the Solomon Islands. Pac Health Dialog 2012;18:166–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filerman G. Closing the management competence gap. Hum Resour Health 2003;1:1–3. 10.1186/1478-4491-1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seims LR, Alegre JC, Murei L, et al. Strengthening management and leadership practices to increase health-service delivery in Kenya: an evidence-based approach. Hum Resour Health 2012;10:25 10.1186/1478-4491-10-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Brouwere V, Van Balen H. Hands-on training in health district management. World Health Forum 1996;17:271–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devadasan N, Elias M. Training Needs Assessment for District Health Managers. Bangalore: Institute of Public Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prashanth NS, Marchal B, Devadasan N, et al. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: a realist evaluation of a capacity building programme for district managers in Tumkur, India. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:42 10.1186/1478-4505-12-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segall M. District health systems in a neoliberal world: a review of five key policy areas. Int J Health Plann Manage 2003;18(Suppl 1):S5–S26. 10.1002/hpm.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conn CP, Jenkins P, Touray SO. Strengthening health management: experience of district teams in The Gambia. Health Policy Plan 1996;11:64–71. 10.1093/heapol/11.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffermann G. Leadership and management quality: key factors in effective health systems. World Hosp Health Serv 2012;48:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smidt A, Balandin S, Sigafoos J, et al. The Kirkpatrick model: a useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2009;34:266–74. 10.1080/13668250903093125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabrizi JS, Gholipour K, Farahbakhsh M, et al. Developing management capacity building package to district health manager in northwest of iran: a sequential mixed method study. J Pak Med Assoc 2016;66:1385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omar M, Gerein N, Tarin E, et al. Training evaluation: a case study of training Iranian health managers. Hum Resour Health 2009;7:20 10.1186/1478-4491-7-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Díaz-Monsalve SJ. The impact of health-management training programs in Latin America on job performance. Cad Saude Publica 2004;20:1110–20. 10.1590/S0102-311X2004000400027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers A. Adults Learning for Development. New York: Cassell Educational Limited, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabbani F, Hashmani FN, Mukhi AA, et al. Hospital management training for the Eastern Mediterranean Region: time for a change? J Health Organ Manag 2015;29:965–72. 10.1108/JHOM-11-2014-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger D, Travis P, Dovlo D, et al. Strengthening management in low income countries; Making Health Systems Work Series. Working Paper 1. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calhoun JG, Dollett L, Sinioris ME, et al. Development of an interprofessional competency model for healthcare leadership. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:375–89. 10.1097/00115514-200811000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarthy G, Fitzpatrick JJ. Development of a competency framework for nurse managers in Ireland. J Contin Educ Nurs 2009;40:346–50. 10.3928/00220124-20090723-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefl ME. Common competencies for all healthcare managers: the Healthcare Leadership Alliance model. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:360–73. 10.1097/00115514-200811000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beanland TJ, Lacey SD, Melkman DD, et al. Multimedia materials for education, training, and advocacy in international health: experiences with the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative CD-ROM. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2006;101:87–90. 10.1590/S0074-02762006000900013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hands-on training in health district management. World health forum. Geneva: World health organization, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquez L, Madubuike C. Country experience in organizing for quality: Zambia. QA Brief 1999;8:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziegler PB, Anyango H, Ziegler HD. The need for leadership and management training for community nurses: results of a Ugandan district health nurse survey. J Community Health Nurs 1997;14:119–30. 10.1207/s15327655jchn1402_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waweru E, Opwora A, Toda M, et al. Are Health Facility Management Committees in Kenya ready to implement financial management tasks: findings from a nationally representative survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:404 10.1186/1472-6963-13-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pal DK, Toppo M, Gupta S, et al. A rapid appraisal of functioning of district programme management units under NRHM in Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Public Health 2009;53:151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rockers PC, Bärnighausen T. Interventions for hiring, retaining and training district health systems managers in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD009035 10.1002/14651858.CD009035.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.