Abstract

Introduction

Clubfoot is a common congenital birth defect, with an average prevalence of approximately 1 per 1000 live births, although this rate is reported to vary among different countries around the world. If it remains untreated, clubfoot causes permanent disability, limits educational and employment opportunities, and personal growth. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to estimate the global birth prevalence of congenital clubfoot.

Methods and analysis

Electronic databases including MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Global Health, Latin American & Caribben Health Science Literature (LILACS), Maternity and Infant Care, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar will be searched for observational studies based on predefined criteria and only in English language from inception of database in 1946 to 10 November 2017. A standard data extraction form will be used to extract relevant information from included studies. The Joanna Briggs Institute appraisal checklist will be used to assess the overall quality of studies reporting prevalence. All included studies will be assessed for risk of bias using a tool developed specifically for prevalence studies. Forest plots will be created to understand the overall random effects of pooled estimates with 95% CIs. An I2 test will be done for heterogeneity of the results (P>0.05), and to identify the source of heterogeneity across studies, subgroup or meta-regression will be used to assess the contribution of each variable to the overall heterogeneity. A funnel plot will be used to identify reporting bias, and sensitivity analysis will be used to assess the impact of methodological quality, study design, sample size and the impact of missing data.

Ethics and dissemination

This review will be conducted completely based on published data, so approval from an ethics committee or written consent will not be required. The results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication and relevant conference presentations.

PROSPERO registration number

Keywords: congenital talipes equinovarus, congenital anomaly of foot, global, clubfoot prevalence, foot deformity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will provide the best evidence on global prevalence of clubfoot, including prevalence in high-income and low-income and middle-income countries.

The results will help us to understand the global burden of disability if clubfoot remains untreated.

The results of this review will provide insight that will assist in programme implementation implication, and will contribute to clubfoot management at a policy level.

As this study will report prevalence from studies on overall birth defects, there is a possibility that it may not represent the true prevalence of clubfoot.

This review may not represent the true population-based birth prevalence of clubfoot.

Introduction

Clubfoot, also known as congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV), is one of the most common structural and visible birth defects and is responsible for major disability in children.1 2 It may affect either one foot or both feet, and is most commonly idiopathic CTEV,3 meaning the causes are not known. Much less commonly, it can also present as syndromic clubfoot which is associated with other congenital anomalies. About half of the infants with clubfoot have bilateral involvements, and unilateral deformity occurs more often on the right side.4 5 Posteromedial ankle and foot soft tissue contractures deform and displace tarsal anlagen, giving rise to characteristic deformities of equinus, heel varus, midfoot adductus and cavus. It has been found that syndromic CTEV is often more severe and more resistant to treatment.6 If the condition remains untreated, the abnormality can lead to long-term functional disability, deformity and pain.7

Context for this review

The majority of children born with clubfoot remain deprived of specialised institutional management, as the formal health systems in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) often lack trained service providers and healthcare provision.8 Often neglected, children with clubfoot are considered a burden to their families. They fail to get access to education and have other social attainments slower than their healthy peers, which may ultimately lead to significant poverty.9 Clubfoot has been identified as one of the major congenital malformations that incurs an immense physical, social and economic burden throughout the life course.10 The outcome of this study will help policy-makers develop strategic and operational guidelines to operate clubfoot treatment with optimum efficiency and effectiveness. Therefore, an estimation of the disease’s burden is essential for planning country-specific prevention and management responses to this public health problem.

Birth prevalence

The global prevalence of clubfoot is estimated to be between 0.6 and 1.5 per 1000 live births with around 80% of all clubfoot cases being born in LMICs.11 12 According to a 2014 estimate by the Global Clubfoot Initiative, the prevalence of clubfoot is 1.4 per 1000 live births in Sweden.13 In Australia, the prevalence is higher among the Aboriginal population than the Caucasian population, at 3.5 and 1.1 per 1000 live births, respectively. The prevalence is 0.76 per 1000 live births in Philippines and 0.9 per 1000 live births in India.14 A study using the pooled data from 10 birth-defect surveillance programmes in the USA showed the overall prevalence of clubfoot was 1.29 per 1000 live births; 1.38 among non-Hispanic whites, 1.30 among Hispanics and 1.14 among non-Hispanic blacks or African-Americans.15 Wynne-Davies reported that the rate is much lower among Asians at about 0.6 per 1000 live births compared with Pacific Islanders at more than 6 per 1000 live births.16 Another study in Uganda found a similar rate of 1.2 per 1000 with a male to female ratio of 2.4:1.17 A recent review conducted by Smythe et al18 revealed that the pooled estimate for clubfoot birth prevalence in LMICs according to WHO regions is 1.11 (0.96 to 1.26) within the Africa region, 1.74 (1.69, 1.80) in the Americas, 1.21 (0.73, 1.68) in South-East Asia (excluding India), 1.19 (0.96, 1.42) in India, 2.03 (1.54, 2.53) in Turkey (Europe region), 1.19 (0.98, 1.40) in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 0.94 (0.64, 1.24) in the West Pacific (excluding China) and 0.51 (0.50, 0.53) in China. In LMICs, birth prevalence of clubfoot varies between 0.51 and 2.03 per 1000 live births.

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to systematically identify, appraise and synthesise the evidence to estimate the global birth prevalence of clubfoot. The specific objectives are to estimate birth prevalence based on (1) different regions developed for Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), (2) high-income countries and LMICs and (3) different ethnicities.

Methods and design

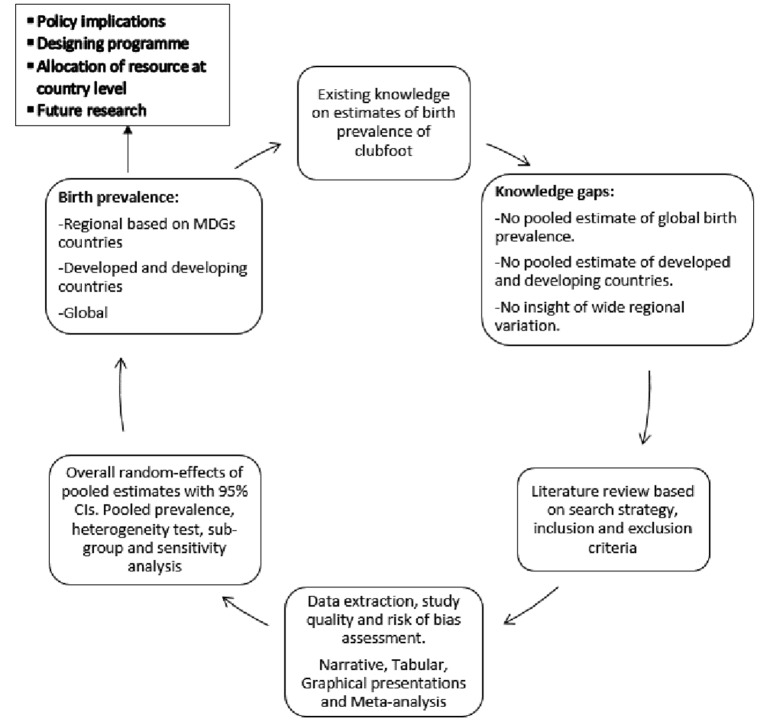

This systematic review protocol was developed according to the recommendations from the ‘CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care’ by Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD), University of York19 and will be reported according to the established Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines.20 The selection process of the studies will be based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and will be reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 flow diagram.21 A systematic search of the literature will be conducted based on the proposed search strategy and databases. A comprehensive database will be developed containing all selected articles for synthesis based on the objectives and proposed conceptual framework (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of systematic review and meta-analysis for birth prevalence of clubfoot. MDGs, Millennium Development Goals.

Study eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Study design

Observational studies including cross-sectional, case–control, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and different medical databases (clinical records, vital statistics data, government surveillance data and reports, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, population censuses and surveys) including birth-defect registries if they meet the inclusion criteria.

Study settings

Population-based or hospital-based studies.

Study population

The study population will be all live birth children being screened for clubfoot. Studies will include a well-defined study population and a reliable estimate of the denominator population. If the birth prevalence is being provided without the number of cases in a well-defined population, then cases will be determined with the given information.

Outcome

Birth outcome with CTEV.

Outcome measures

Birth prevalence of clubfoot, that is, the number of cases of CTEV per 1000 live births. As prevalence and incidence data are often reported as a proportion, so for pooling of proportion during meta-analyses, prevalence estimates will be transformed to logit to improve their statistical properties, and these will then be converted back to prevalence.

Date of publication

Studies reporting in the databases covering the period from inception of databases in 1946 to 10 November 2017 will be considered for review.

Language of publications

Only literature published in English will be included.

Type of publications

All relevant studies, regardless of publication status, will be included in order to avoid publication bias. The inclusion of conference abstracts and interim results will also be considered. Study authors will be contacted if full study details are required. Data from conference abstracts will be carefully considered, to avoid the differences between data reported in conference abstracts and their corresponding full reports. ‘Partially published research’ (conference abstracts) will be classified as ongoing studies and will be reviewed.

Exclusion criteria

Study design

Intervention studies (controlled or uncontrolled), prognostic studies that look at associations between prognostic factors and subsequent outcomes or complications, ecological studies, case series, case reports and qualitative studies.

Publication type

No restrictions on publication type.

Population

The proposed review will exclude studies not reporting the prevalence of clubfoot from birth and studies where the source of the population is ambiguous and information is not provided as to whether all children were screened.

Search strategy and literature sources

The search strategy will be constructed taking into account the ‘PICO’ (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) framework. As mentioned earlier, we will only focus on population and outcome as this review will report prevalence of clubfoot on reported live births. The following approaches will be used to locate relevant studies.

Searching electronic databases

The selection of electronic databases for research will be focused on the review topic. Lists of databases will be accessed from library. MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Global Health, Latin American & Caribben Health Science Literature (LILACS), Maternity and Infant Care, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar will be searched to identify relevant studies.

Visually scanning reference lists from relevant studies

Reference lists of papers (both primary studies and reviews) that have been identified by the database searches will be browsed to identify further studies of interest.

Hand searching key journals and conference proceedings

Hand searching will be done by scanning the content of journals page by page to identify very recent publications that may not have been included and indexed by electronic databases and to include articles from journals that are not indexed by electronic databases. The selection of journals to hand search will be made by analysing the results of the database searches and identifying the journals that contain the largest number of relevant sources. Selecting journals to hand search will be finalised by analysing the results of the database searches to identify the journals that contain the largest number of relevant studies.

Contacting study authors

Study authors will be contacted if a full-text publication cannot be accessed for free. Topic experts will be requested to check the list to identify any known missing studies.

Searching relevant internet resources

Published literature will be retrieved by web browsing using search engines such as Google and Google Scholar. Internet searching will be done to retrieve published literature.

Citation searching

Citation searching will involve selecting the key papers already identified for inclusion in the review, and then searching for articles that have cited these papers.

Constructing search strategy

Search strategies will be designed to be highly sensitive so as many potentially relevant studies as possible are retrieved. If the precision of the search strategy is increased, all relevant studies will be carefully considered so that none are missed. We will be careful not to miss any relevant studies if the precision of the search strategy is increased after the initial screening search.

In order to construct an effective combination of search terms, the review question will be broken down into ‘concepts’. Population, intervention, comparator and outcome elements from PICO will be used to structure the search. Since the review will look for incidence of clubfoot, and there will be no intervention or comparison, the search strategy will only focus on population and outcome. Advice will be sought from the topic experts on the review team and advisory group.

Search language

The search and selection strategies will be drawn on established systematic review methods as outlined by the CRD. The preliminary search strategy was developed from the MEDLINE (table 1) which will be used for CINAHL, Embase, Global Health, LILACS, Maternity and Infant Care, Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar to identify relevant studies. Table 1 shows the basic search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE.

Table 1.

Search strategy used in Ovid MEDLINE from inception of database in 1946 to 10 November 2017

| Number | Search terms | Results |

| 1 | Clubfoot/ | 3708 |

| 2 | (Clubf??t or club-f??t).mp. | 4379 |

| 3 | (talipes adj2 equinovarus).mp. | 663 |

| 4 | (talipes adj2 equino-varus).mp. | 44 |

| 5 | pie torcido*.mp. | 0 |

| 6 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 | 4583 |

| 7 | incidence/or prevalence/ | 487 648 |

| 8 | exp Medical Records/ | 139 693 |

| 9 | exp Population Surveillance/ | 65 042 |

| 10 | (inciden* or prevalen* or occurrence* or medical record* or health record* or surveillance* or frequency*).mp. | 2 483 556 |

| 11 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 | 2 510 094 |

| 12 | 6 and 11 | 500 |

| 13 | exp Lower Extremity Deformities, Congenital/ | 9499 |

| 14 | ((lower limb* or foot* or feet*) adj3 (defect* or malform* or abnormalit*)).mp. | 1667 |

| 15 | 13 or 14 | 10 715 |

| 16 | 11 and 15 | 1005 |

| 17 | 12 or 16 | 1151 |

Note. This search strategy will be checked for MeSH term and used for other electronic databases.

MeSH, Medical Subject Headings.

Documenting the search

The search process will be reported in sufficient detail so that it could be rerun at a later date. The search will be documented by recording the process and the results contemporaneously. All searches, including internet searches, hand searching and contact with experts will be recorded. The website, uniform resource locator, the date searched, any specific sections searched and the search terms used will be reported and a citation in EndNote will be created.

Study selection and data management

Study selection will be conducted in two stages: an initial screening of titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria to identify potentially relevant papers followed by screening of the full papers that were identified as possibly relevant in the initial screening. Two researchers (AA and MM) will screen titles and abstracts and then full papers, and there will be a third reviewer in case of any disagreement on selection. In case of disagreement, the two reviewers will sit together to resolve the disagreement between themselves. If a consensus cannot be reached, a third reviewer (AER) will be involved. The third reviewer will screen the title/abstract/paper against the inclusion and exclusion criteria about study eligibility.

The selection of studies from electronic databases will be conducted in two stages.

Stage 1

Decision to include an article will be based on titles, source of the article (where available) and abstracts. Articles will be assessed against the predetermined inclusion criteria. If an article does not meet the inclusion criteria, then it will be rejected right away. The decision will be made based on the agreement of the reviewers. If there is any disagreement between the two reviewers (AA and MM), the third reviewer will be involved for decision (AER). We might allow overinclusion during this first stage. Rejected citations will be classified into two main categories; those that are clearly not relevant and those that address the topic of interest but fail on one or more criteria. The first category will be recorded as an irrelevant study, with the reason being listed as ‘irrelevant’. The second category will be recorded as a study that is excluded, and the specific reason for it not meeting the inclusion criteria will be recorded. This will increase the transparency of the selection process. The selection process for the review will be explained in the flow chart (figure 1) which will be adopted from the PRISMA study flow diagram of study-selection process.

Stage 2

For studies that appear to meet the inclusion criteria, or in cases where a definite decision cannot be made based on the title and/or abstract of studies alone, the full paper will be obtained for detailed assessment against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Direct access to full papers will be explored during hand searching of journals or by contacting the authors. To increase the reliability of the decision-making process and to ensure reproducibility, all papers will be independently assessed by two researchers (AA and MM).

Piloting the study selection process

The selection process will be piloted by applying the inclusion criteria to a sample of papers in order to check that they can be reliably interpreted and that the studies are classified appropriately (according to stages 1 and 2 mentioned earlier). The pilot phase will be used to refine and clarify the inclusion criteria and ensure that the criteria can be applied consistently by the two researchers (AA and MM). Piloting will also give an indication of the likely time needed for the full selection process.

Blinding

The assessment by two independent researchers will be non-blinded.

Dealing with duplication

Duplicate publications of research results will be looked for to ensure they are not treated as separate studies in the review. When multiple reports of a single study are identified, they will be treated as a single study but reference will be made to all the publications.

Data extraction

One of two reviewers (AA and MM) using predefined data extraction sheets adopted from Cochrane Public Health Group Data Extraction and Assessment Template22 will extract relevant information from included studies (online supplementary file 1). The extracted data will include information on the study (eg, year of conduct, journal name, title of the study, authors name, year of publication, country of conduct, design, study setting, sample size and study quality items) and outcomes (birth). Any missing statistical parameters of importance (eg, incidence proportion or cumulative incidence, and incidence rate) and variability measures (eg, 95% CIs, P values) will be calculated, if data permits, or authors of the primary studies will be contacted. All calculated or derived data will be denoted as ‘calculated’ and will be incorporated in the extraction sheets. The data extracted will be cross-checked. Any disagreements regarding the extracted data will be resolved between the two reviewers or through a consensus or adjudication of a third reviewer, if needed. Data extraction forms will be piloted on a sample of included studies to ensure that all the relevant information is captured, and that resources are not wasted on extracting data which are not required.

bmjopen-2017-019246supp001.pdf (407.2KB, pdf)

Study quality and risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of included studies will be appraised by two independent reviewers (AA and MM). Quality will be assessed considering the appropriateness of the study design to the research objective, risk of bias, choice of outcome measure, quality of reporting and generalisability. We will define study quality primarily in relation to a study’s internal validity, although we will also note how other types of validity—statistical conclusion validity, construct validity and external validity—are relevant to the study quality assessment in the context of the proposed systematic review.

The quality appraisals will be cross-checked, and any disagreements will be resolved by a consensus-based discussion or through a third reviewer, if necessary. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) appraisal checklist will be used to assess the overall quality of studies reporting prevalence (online supplementary file 2).23 24

bmjopen-2017-019246supp002.pdf (190KB, pdf)

Data analysis and synthesis

Narrative synthesis

A descriptive summary with data tables will be produced to summarise the literature. Both a narrative synthesis and, where possible, a quantitative analysis of the data will be presented. For narrative synthesis, we will use ‘Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews’.25 Studies will be clustered according to design and setting (hospital based and population based). After the studies have been grouped into common clusters, their characteristics (including their specific design and study details and a description of the number and characteristics of the study participants included) will be presented in summary tables. The evidence for prevalence of clubfoot will be presented separately according to regional variation. The regions will be based on low-income/middle-income and high-income regions defined by MDGs.26

Statistical analysis

Pooled analysis

In the meta-analysis, pooled prevalence of clubfoot on a global scale will be assessed using the well-established inverse variance-weighted method. The score CI will be constructed for individual estimates, which outperforms the Wald and exact CIs even in small samples.27 28 The pooled CI will be constructed after applying the variance stabilising transformation of the proportions for achieving the asymptotic normality of the estimate. This will allow us to calculate the Wald CI for the pooled estimate. The analysis will be carried out using Stata V.14.0 (StataCorp).

Test of heterogeneity

To assess heterogeneity of the event rates across studies, we will use the Q-statistic test and the I2 statistic. If the test for heterogeneity denoted as I2 (if I2≤25%), studies will be considered homogeneous.29

Subgroup analysis

Stratified prevalence will be generated by the economic levels of the high-income countries and LMICs, by sampling methods (random and convenience sampling), by type of questionnaires used (validated and non-validated) and ethnicity.

Assessment of publication bias

To address the publication bias, we will use a contour-enhanced funnel plot and a statistical test for asymmetry. To address reviewer selection bias, we will seek individual participant’s data where possible to examine additional heterogeneity between trials.30

Sensitivity analysis

We will conduct a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of methodological quality, study design, sample size, effect of missing data and geographical variations, aetiology of idiopathic and syndromic clubfoot, as well as the analysis methods of the review results. To investigate the suspected asymmetry of the funnel plot due to publication bias, we will also conduct sensitivity analyses.

Discussion

This systematic review will identify and summarise the relevant evidence on the burden of clubfoot in terms of birth prevalence. Strengths and limitations (eg, exclusion of non-English studies, inclusion of conference abstracts, etc) of the review will be discussed and gaps in the evidence will also be highlighted. The findings of this review and those of other similar reviews will be compared (if identified) for the degree of consistency.

Secondary analysis of data has been shown to be helpful in describing the epidemiology of clinical conditions. The estimates generated through analysis of secondary data is considered more reliable if the data is validated and linked across a registry system (primary-care and secondary-care sectors). Such validation work needs prioritisation. This review will aid in providing a pulled estimate of clubfoot prevalence, and also the burden of this birth defect globally.

Since we have decided to limit our search to English language publications, we may miss relevant articles which are published in other languages. However, due to the major shift towards the publication of studies in English, the extent and effects of language bias may have recently been reduced.31

Presenting and reporting of results

The proposed conceptual framework will be guided by the systematic review and meta-analysis. The results of the study will be reported as per MOOSE guidelines and findings of the search strategy as per PRISMA-P flow diagram.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support and guidance of Dr. K. M. Saif-Ur-Rahman, Dr Shahed Hossain and Dr Mohammed Abdus Salam of icddr,b.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA is the guarantor. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the protocol as follows. AA worked on the topic refinement, formulation of research question, review design, study selection forms, data extraction sheets, plan of analysis and wrote the protocol, AA designed the search strategy under the supervision of DMEH, SEA, SPP, LR and RGM. DMEH, AER and LR contributed to the topic refinement, formulation of research question, review design, plan of analysis and feedback on critical intellectual content of the draft protocol. LR, MMR, TM and MRH reviewed the manuscript for feedback. MM will review the articles and do the data extraction along with AA. MAM and MABS will provide database management and conduct literature search/handle the bibliography. As the senior author, DMEH supervised the preparation of the study protocol and the addressing of the reviewers’ comments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Aggarwal A, Gupta N. The role of pirani scoring system in the management and outcome of idiopathic club foot by ponseti method. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penny JN. The neglected clubfoot. Techniques in Orthopaedics 2005;20:153–66. 10.1097/01.bto.0000162987.08300.5e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werler MM, Yazdy MM, Mitchell AA, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of idiopathic clubfoot. Am J Med Genet A 2013;161A:1569–78. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung CS, Nemechek RW, Larsen IJ, et al. Genetic and Epidemiological Studies of Clubfoot in Hawaii. Hum Hered 1969;19:321–42. 10.1159/000152236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeValentine SJ. Foot and ankle disorders in children: Churchill Livingstone, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janicki JA, Narayanan UG, Harvey B, et al. Treatment of neuromuscular and syndrome-associated (nonidiopathic) clubfeet using the Ponseti method. J Pediatr Orthop 2009;29:393–7. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181a6bf77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staheli L. Clubfoot: ponseti management Ponseti management. 3rd ed Seattle, WA: Global Help Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewin S, Lavis JN, Oxman AD, et al. Supporting the delivery of cost-effective interventions in primary health-care systems in low-income and middle-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Lancet 2008;372:928–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61403-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McElroy T, Konde-Lule J, Neema S, et al. Understanding the barriers to clubfoot treatment adherence in Uganda: a rapid ethnographic study. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:845–55. 10.1080/09638280701240102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobbs MB, Gurnett CA. Update on clubfoot: etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:1146–53. 10.1007/s11999-009-0734-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christianson A, Howson CP, Modell B. March of Dimes: global report on birth defects, the hidden toll of dying and disabled children. White Plains, NY: March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dobbs MB, Nunley R, Schoenecker PL. Long-term follow-up of patients with clubfeet treated with extensive soft-tissue release. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:986–96. 10.2106/JBJS.E.00114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallander H, Hovelius L, Michaelsson K. Incidence of congenital clubfoot in Sweden. Acta Orthop 2006;77:847–52. 10.1080/17453670610013123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.INITIATIVE GC. What is clubfoot, 2016. http://globalclubfoot.org/clubfoot/ (accessed 29 Mar 2016).

- 15.Parker SE, Mai CT, Strickland MJ, et al. Multistate study of the epidemiology of clubfoot. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009;85:897–904. 10.1002/bdra.20625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wynne-Davies R. Family studies and the cause of congenital club foot. Bone & Joint Journal 1964;46:445–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathias RG, Lule JK, Waiswa G, et al. Incidence of clubfoot in Uganda. Can J Public Health 2010;101:341–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smythe T, Kuper H, Macleod D, et al. Birth prevalence of congenital talipes equinovarus in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:269–85. 10.1111/tmi.12833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination UoY. Systematic Reviews CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care: York Publishing Services Ltd, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Jama 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;338:332 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochrane data abstraction. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors (accessed 9 Nov 2017).

- 23.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, et al. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2014 The systematic review of prevalence and incidence data. Adelaide, SA: The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med 2015;8:2–10. 10.1111/jebm.12141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Way C. The millennium development goals report 2015: UN, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 1998;17:857–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agresti A, Coull BA. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. The American Statistician 1998;52:119–26. 10.1080/00031305.1998.10480550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoque DME, Kumari V, Hoque M, et al. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183667 10.1371/journal.pone.0183667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019246supp001.pdf (407.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019246supp002.pdf (190KB, pdf)