Abstract

Objective

We assessed the mediating effects of metabolic components on the relationship between fruit or vegetable intake and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

This study was conducted using data from the 2013–2015 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which is a national representative cross-sectional survey to assess health and nutritional status in the Korean population.

Method and analysis

A total of 9040 subjects (3555 males and 5485 females) aged ≥25 years were included in the study. Physician-diagnosed CVD via self-report was used as the outcome. Fruit or vegetable intake was measured via a dish-based semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire and grouped into categories (<1 time/day, 1 time/day, 2 times/day and ≥3 times/day). Systolic blood pressure (SBP), cholesterol and fasting glucose were considered metabolic mediators, and the bootstrap method was used to assess mediating effect.

Results

About 1.8% of adults aged 25–64 years had CVD. According to the result of ‘process’ macro, the confounder-adjusted risk for CVD decreased by 14% (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98) as fruit, but not vegetable, intake was increased by one unit per day. After additional adjustment for three metabolic factors simultaneously, the OR was attenuated to 0.89 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.03). This result indicates that the indirect effect of three metabolic factors accounted for 21.4% of the relationship between fruit intake and CVD. SBP was a more important metabolic mediator than the other factors. The indirect effect by metabolic factors accounted for 30.0% when body mass index was additionally controlled as a mediator, and SBP still had an independent effect compared with the other mediators.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that controlling SBP may lessen the CVD risk, and a diet rich in fruits can regulate SBP which, in turn, reduces CVD risk.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, blood pressure

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this study, we assessed how fruit or vegetable intake is related to cardiovascular disease by assessing the indirect effect of systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and fasting glucose, including body mass index. Given studies were not interested in this topic, so this study has scientific value.

Using national representative data source, we sought to generalise the research findings.

However, these results were derived from a cross-sectional study design, so causal relationships could not be effectively drawn. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the interpretation of research results.

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are responsible for mortality worldwide; a report from the WHO stated that CVDs accounted for 31% of all deaths worldwide in 2015.1 Although mortality from ischaemic heart disease has shown a flat trend and that from cerebrovascular disease has shown a declining trend in the Republic of Korea since 2005, these causes of death remain highly ranked.2

Several risk factors for CVDs, including metabolic factors, such as high glucose, high blood pressure and high cholesterol, have been suggested.3 Several studies have suggested that these metabolic factors are also linked to risk factors (eg, body mass index (BMI) and dietary factors) and CVD risk as mediators.4 5 The causal link between these mediators and disease risk can help explain how intervention of risk factors works. However, previous studies focused on a single relationship between a risk factor and a disease rather than the mediating effects.

Excessive risk for CVD caused by poor diet and chronic diseases was reported from a study of global burden of disease (GBD). In addition, the GBD study established possible causal mediating relationships between a diet poor in fruits or vegetables, metabolic mediators (blood pressure, cholesterol and glucose) and disease.4 Moreover, a recent meta-analysis reported that the beneficial effects of fruits and vegetables intake were also shown in CVD, as well as in cancer and all-cause mortality.6 The metabolic mediators mentioned above have also been linked to BMI and CVD.4 The effect of a diet rich in fruits and vegetables on BMI has been reported through epidemiological studies,7 but few studies have assessed BMI as a mediator.

There is a need to study the degree to which these metabolic factors contribute to the relationship between risk factors and disease. Although the evidence for the association between fruit/vegetable intake and CVD is relatively strong,8 9 clarifying the potential biological pathway mechanisms could substantially add to our knowledge. Thus, using cross-sectional survey data from the 2013–2015 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), we assessed the mediating effects of metabolic components applied to a confirmatory model. Furthermore, we assessed how the BMI contributes to the relationship between fruit or vegetable intake and CVD as a confounder or mediator.

Methods

Study subjects

This study was conducted using data from the 2013–2015 KNHANES, which is a national representative cross-sectional survey to assess health and nutritional status in the Korean population (response rate=78.3%). It consists of a health interview, health examination and a nutrition survey. A number of variables were collected by trained staff, including physicians, medical technicians and dietitians. The detailed KNHANES survey method has already been described.10

The food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was changed to a dish-based semiquantitative FFQ based on a 2012 survey. The survey assessed subjects 19–64 years of age. Details regarding the development process and validation results of the FFQ tool have been previously published elsewhere.11 12 We used the sixth survey from 2013 to 2015 by sampling according to the survey cycle. This study included subjects ≥25 years. Additionally, the eligible study population included the respondents with data from all three parts of the survey. Of the subjects aged 25–64 who participated in the survey (n=12 258), 73.7% participated in all three parts of the survey. A total of 9040 subjects (3555 males and 5485 females) were included in the study.

Fruit and vegetable intake

The dish-based semiquantitative FFQ was composed of 112 items and provided information on typical dietary consumption for 1 year using a nine-point scale (less than once per month or never, once per month, two to three times per month, once per week, two to four times per week, five to six times per week, once per day, twice per day and three times per day) and three levels to represent the amount consumed by referring to a standard amount (less, standard and more). Based on a previous study,4 we excluded pickled and salted vegetables, kimchi and fruit juice. Vegetable intake and fruit intake were evaluated based on 15 items and 12 items, respectively (online supplementary table 1). The frequency of fruit intake was used after adjusting for seasonal fruit. Estimated intakes of fruits and vegetables were calculated on the FFQ by multiplying the frequency of each food (as described above) by the selected amount consumed: small (0.5), medium (1) and large (1.5). Fruit and vegetable intake was expressed in four categories (<1 time/day, 1 time/day, 2 times/day and ≥3 times/day).

bmjopen-2017-019620supp001.pdf (279.8KB, pdf)

Outcome and covariate data

We used data from the health-related questionnaire for the diseases diagnosed by physicians. We selected the questions about stroke, myocardial infarction and angina pectoris for the CVD-related diseases. If a subject answered ‘yes’ to any of the three diseases, we considered that the subject had CVD. Additionally, we separately considered subjects who answered ‘yes’ on the question about current illness with a physician’s diagnosis and those who responded ‘yes’ to a question about receiving treatment for a disease.

Using the measured height and weight information, BMI was calculated in units of kg/m2. Blood pressure was measured three times in total, and the average value of the second and third measurements was used. Total cholesterol and glucose were measured by taking blood from fasting state.

We used data on sex, age, quartiles of income, region (urban/rural), current smoker and survey year as covariates through a literature review13 and the results of a univariate analysis. We used quartile data for income instead of education level as a socioeconomic indicator because income may be directly linked to food purchases.14 The question about physical activity was changed from the 2014 survey, so we did not consider physical activity.

Statistical analysis

The basic characteristics of the study subjects are presented as weighted percentages or weighted means with SEs by considering the multistage sampling survey method. The distributions of the basic characteristics according to fruit or vegetable intake level were assessed using the trend test under the random sampling condition. In the main analysis, CVD was considered the outcome (Y), and fruit or vegetable intake was considered an independent variable (X). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) (M1), total cholesterol (M2) and fasting glucose (M3) were applied as metabolic mediators (M). Additionally, BMI was considered as either a covariate or mediator.

We used the ‘process’ macro based on the bootstrap method (V.2.16.3) suggested by Andrew to assess the mediating effects.15 In this analysis, we applied 10 000 bootstraps. We separately or simultaneously assessed the indirect effect of the metabolic mediators on the association between dietary factors and CVD. First, we examined the association under the controlling covariates (sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), present smoking and survey year) through four basic steps to assess mediation.16 Step 1: association between dietary factors and CVD (X → Y; total effect and was marked path ‘c’); step 2: association between dietary factors and metabolic mediators (X → Mi; marked path ‘a’); step 3: association between metabolic mediators and CVD after controlling for metabolic mediators (Mi → Y; marked path ‘b’); and step 4: association between dietary factors and CVD disease after controlling for metabolic mediators (direct effect; marked path ‘c'’). Subsequently, we evaluated the multiple mediator model and the serial mediator model.

The exponential regression coefficient is equal to the OR when considering the CVD as an outcome variable. The percentage of risk mediated by the metabolic mediator was calculated as17: OR (confounder adjusted) − OR (confounder and mediator adjusted)/OR (confounder adjusted) − 1×100.

All statistical analyses were conducted under a random sampling condition excluding the basic characteristics given in table 1 using SAS V.9.4 software. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the study subjects

| Weighted % (SE) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 49.92 (0.51) |

| Female | 50.08 (0.51) |

| Age range | 25–64 years |

| Age (years)* | 43.68 (0.18) |

| Region | |

| Urban | 83.87 (1.52) |

| Rural | 16.13 (1.52) |

| Income level (quartiles) | |

| Q1 | 23.46 (0.73) |

| Q2 | 25.61 (0.72) |

| Q3 | 25.03 (0.71) |

| Q4 | 25.90 (0.97) |

| Current smoking | |

| No | 75.83 (0.60) |

| Yes | 24.17 (0.60) |

| Disease | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.81 (0.16) |

| Stroke | 0.98 (0.13) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 0.90 (0.10) |

| Metabolic factors* | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 115.01 (0.21) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.98 (0.47) |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 98.58 (0.30) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.92 (0.05) |

*Weighted mean with SE.

Results

The basic characteristics of the study subjects are presented in table 1. Mean age was 43.7 years, and 1.81% of subjects (n=189) had CVD. In addition, 0.98% and 0.90% of subject had stroke (n=102) and ischaemic heart disease (n=97), respectively. Subjects with a higher income ate more fruits or vegetables than those with a lower income. Those who ate more fruit were more likely to be non-smokers and female than their counterparts (online supplemental tables 2 and 3).

The total effect of fruit intake on CVD showed an inverse association without controlling for metabolic mediators (adjusted OR (aOR) 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98), but the effect of vegetable intake was not significant (aOR 0.93; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.06) after controlling for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoker and survey year (data not shown).

The direct effect of fruit intake on CVD was borderline significant after further considering each metabolic mediator. The effect of fruit intake on SBP (X → M) and the effect of SBP on CVD (M → Y) were significant, and subsequently the indirect effect of SBP did not include zero in the 95% CI range, unlike other metabolic mediators. The effect of fruit intake on BMI showed borderline significance, and the effect of BMI on CVD was significant, but the indirect effect of BMI was not significant. Additionally, the effect of SBP was significant even after controlling for BMI as a covariate (table 2). SBP, cholesterol and BMI were associated with CVD, but vegetable intake did not contribute to either metabolic mediator or CVD (table 3). The mediating effect of SBP on the association between fruit intake and outcome was dominant even when the outcome was restricted to those with a current illness or undergoing treatment.

Table 2.

The effect of metabolic mediators (M) in the association between fruit intake (X) and cardiovascular disease (Y)

| Metabolic factors (M) |

Fruit intake | |||||||||||

| X → M (a) | M → Y (b) | X → Y (c′=direct effect) |

Indirect effect (a*b) | |||||||||

| β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | SE | p | β | 95% CI | ||

| SBP* | −0.484 | 0.144 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.137 | 0.072 | 0.06 | −0.007 | −0.014 | −0.002 |

| TC* | −0.156 | 0.357 | 0.66 | −0.019 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | −0.144 | 0.075 | 0.05 | 0.003 | −0.011 | 0.017 |

| FPG* | −0.665 | 0.217 | <0.01 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.20 | −0.144 | 0.074 | 0.05 | −0.002 | −0.006 | 0.001 |

| BMI* | −0.059 | 0.034 | 0.08 | 0.078 | 0.022 | 0.001 | −0.143 | 0.072 | <0.05 | −0.005 | −0.012 | 0.001 |

| SBP† | −0.420 | 0.139 | <0.01 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.01 | −0.127 | 0.072 | 0.08 | −0.005 | −0.011 | −0.0004 |

| TC† | −0.064 | 0.352 | 0.86 | −0.019 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | −0.126 | 0.075 | 0.09 | 0.001 | −0.012 | 0.015 |

| FPG† | −0.614 | 0.214 | <0.01 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.42 | −0.130 | 0.074 | 0.08 | −0.002 | −0.005 | 0.002 |

All analyses were performed separately according to each metabolic mediator.

*Adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoking and survey year.

†Adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoking, survey year and BMI.

BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol;.

Table 3.

The effect of metabolic mediators (M) in the association between vegetable intake (X) and cardiovascular disease (Y)

| Metabolic factors (M) |

Vegetable intake | |||||||||||

| X → M (a) | M → Y (b) | X → Y (c′=direct effect) |

Indirect effect (a*b) | |||||||||

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | SE | P | β | 95% CI | ||

| SBP* | −0.042 | 0.169 | 0.80 | 0.014 | 0.004 | 0.002 | −0.132 | 0.086 | 0.13 | −0.001 | −0.006 | 0.004 |

| TC* | 0.236 | 0.420 | 0.57 | −0.019 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | −0.121 | 0.089 | 0.18 | −0.005 | −0.021 | 0.012 |

| FPG* | −0.054 | 0.256 | 0.83 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.18 | −0.132 | 0.088 | 0.14 | −0.0002 | −0.003 | 0.002 |

| BMI* | 0.057 | 0.040 | 0.16 | 0.080 | 0.022 | <0.001 | −0.145 | 0.086 | 0.09 | 0.005 | −0.002 | 0.013 |

| SBP† | −0.114 | 0.163 | 0.48 | 0.012 | 0.005 | 0.01 | −0.131 | 0.086 | 0.13 | −0.001 | −0.006 | 0.002 |

| TC† | 0.142 | 0.415 | 0.73 | −0.019 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | −0.122 | 0.089 | 0.17 | −0.003 | −0.019 | 0.014 |

| FPG† | −0.121 | 0.252 | 0.63 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.4 | −0.132 | 0.088 | 0.14 | −0.0003 | −0.003 | 0.002 |

All analyses were performed separately according to each metabolic mediator.

*Adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoking and survey year.

†Adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoking, survey year and BMI.

BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol.

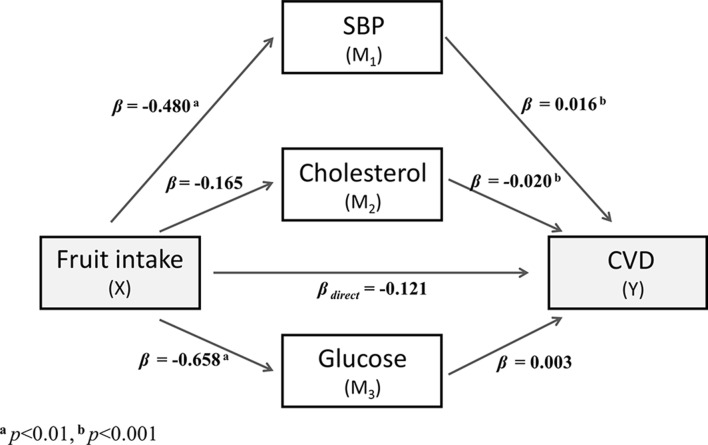

When the beta coefficient was expressed as OR, the OR of the effect of fruit intake on CVD was attenuated to 0.89 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.03) while simultaneously controlling for three metabolic mediators, indicating a 21.4% indirect effect for CVD (ie, (0.8555–0.8864)/(0.8555–1)*100=21.4%). SBP showed an independent indirect effect. Higher fruit intake had a beneficial effect on fasting glucose, but its effect was not associated with CVD. The direct effect of fruit intake on CVD presented an inverse association (ß=−0.121, P=0.11), but it did not reach statistical significance (figure 1). In addition, similar results were observed when adding BMI as covariate, with an OR (the effect of fruit intake on CVD) of 0.90 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.04; data not shown). The indirect effect of the four metabolic factors accounted for 30.0% of the relationship between fruit intake and CVD (ie, (0.8555–0.8989)/(0.8555–1)*100=30.0%).

Figure 1.

The effect of multiple metabolic factor (Mi) mediators in the association between fruit intake (X) and CVDs (Y). Coefficients were adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoker and survey year using the bootstrapping method. aP<0.01; bP<0.001. CVD, cardiovascular disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

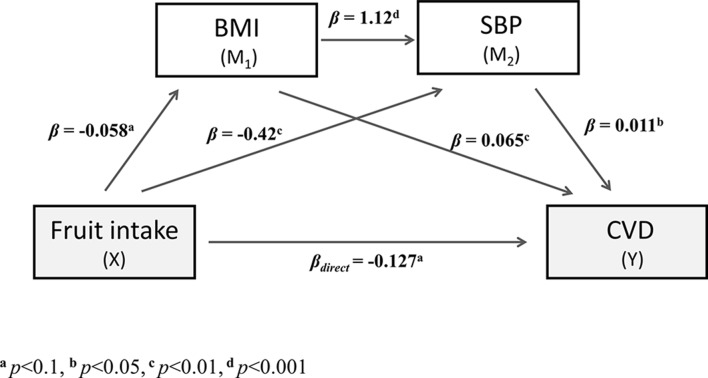

We analysed the serial mediator model to assess whether BMI influenced SBP (figure 2). Although the effect of fruit intake on BMI showed borderline significance, the influence of BMI on SBP and the effect of SBP on CVD reached statistical significance. Of the three possible indirect paths, the fruit intake path → SBP → CVD was the only one to show an independent association.

Figure 2.

The effect of multiple serial mediators of metabolic factors (Mi) in the association between fruit intake (X) and cardiovascular diseases (Y). Coefficients were adjusted for sex, age, income, region (urban/rural), current smoker, and survey year using the bootstrapping method. aP<0.1, bP< 0.05, cP<0.01, dP< 0.001. BMI, body mass index, SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Fruit intake was directly linked to subjects who suffered a stroke, but not ischaemic heart disease, regardless of which metabolic factors were controlled. In addition, the mediating effect of SBP was dominant in patients who suffered a stroke or ischaemic heart disease even after controlling for BMI (online supplemental tables 4 and 5).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed how fruit or vegetable intake is related to CVD by assessing the indirect effect of metabolic mediators. Based on the suggested causal link, SBP, total cholesterol and fasting glucose were considered metabolic mediators, and the effect of BMI was additionally assessed. Of them, the indirect effect of SBP on the relationship between fruit intake and CVD was significant even after considering BMI, but not vegetable intake. The indirect effect of the four metabolic factors accounted for 30.0% of the relationship between fruit intake and CVD.

The beneficial effects of high fruit or vegetable intake on CVD and the unfavourable effects of high blood pressure, glucose and cholesterol on CVD are well known. Thus, previous studies considered metabolic factors together, and mediators were reported to attenuate the association of a direct effect.5 One large prospective study conducted in 10 regions in China indicated that higher fresh fruit intake is linked to CVD death, and its effect was attenuated by HRs from 0.63 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.72) to 0.70 (95% CI 0.61 to 0.79) after adjusting for BMI, blood pressure, glucose and waist circumference.18 Another study conducted in Shanghai, China, showed an attenuated association between fruit intake and incident coronary heart disease after controlling for a history of diabetes, hypertension or dyslipidaemia, but no association or attenuation was observed for vegetable intake.5 The Women’s Health Study reported by Liu et al19 also showed that the effect of fruits and vegetables on CVD risk became stronger after excluding subjects with a history of diabetes, hypertension and high cholesterol. It seems that these mediators largely attribute to the relationship between fruit and/or vegetable intake and CVD risk. However, biological pathways by metabolic factors between fruit and/or vegetable intake and CVD risk have not been investigated.

The assessment of a mediating effect could help understand how fruit and/or vegetable intake affects CVDs. In addition, an effect of poor dietary risk by metabolic mediators on CVD was suggested by the GBD study, so that was considered to estimate the disease burden. The mediating effect of blood pressure on the association between fruit and/or vegetable intake and CVD was suggested by a prospective cohort study of patients in the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.13 Blood pressure contributed 22.2% to the relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and CVD death. This was similar to the results adjusted for BMI, cholesterol and blood pressure. That study also showed that the direct effect of fruit and vegetable intake was notable in patients who suffered a stroke but not those with ischaemic heart disease. These results are in line with those of the present study.

We assessed a potential role for BMI on the association between fruit intake and CVD using various models. Several reports, including the above-mentioned study, considered BMI as a potential mediator.13 18 Additionally, a causal link between BMI and CVD risk is mediated through metabolic factors. Two pooled studies of prospective cohorts assessed the effect of BMI on coronary heart disease and stroke as mediated by metabolic components. They reported that blood pressure was a more important mediator compared with cholesterol and glucose.17 20 Other pooled data from an Asian cohort also indicate that estimated mediating proportions through hypertension were 62.3%, 35.7% and 92.4% for the association between BMI and death due to CVD, coronary heart disease and stroke, respectively, but not by diabetes.21 The GBD study restricted total calories to 2000 kcal instead of considering BMI.22 In the present study, higher fruit intake was inversely associated with BMI, but it was borderline significant (β=−0.06, P=0.08), which affected the results of the fruit intake path → BMI → SBP → CVD in the serial multiple mediator model. Our study found that the mediating effect due to BMI was about 7.9%, but previous studies showed a <3.0% mediating effect by BMI on the association between fruit only or fruit and vegetable intake and CVD deaths by presenting little change in the adjusted risk value.13 18 However, it is difficult to make a direct comparison due to discrepancies in study design, study populations, the definition of disease and fruit and/or vegetable intake.

Eating more vegetables was not significantly associated with either a direct or indirect effect. In Korea, vegetables in the general population are easily accessible by a side dish. Indeed, statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have reported that daily vegetable consumption among adults was the highest in Korea.23 However, the manner of preparation and/or cooking can influence nutrient content.7 The favourable effects of fruit and vegetable intake can be explained by nutrients, such as dietary fibre, folate, potassium and antioxidant vitamins (ie, vitamin E, vitamin C, polyphenols, flavonoids and carotenoids) and other components. These nutrients might be involved with controlling glucose, lipid level, and blood pressure and reducing the risk of CVD along with weight control.7 However, because foods contain various nutrients, food recommendations help subjects follow a prevention strategy. In addition, healthy eating is also associated with other health behaviours, such as not smoking and regular physical activity.13 24

The present study has some limitations. First, the results were derived from a cross-sectional study design, so causal relationships could not be effectively drawn. Our study design is also open to the problem of reverse causation. If the reverse causation affects the results, the association will appear to be null or reverse direction to what is expected. However, the indirect effect by SBP was significant, and some parts of our results were consistent with previous studies.13 24 Furthermore, the results were also consistent when stroke and ischaemic heart disease were analysed separately. Because the survey was conducted through a household visit and excludes people in the hospital, subjects with diseases might be the relatively less serious cases. Measurement error in FFQ survey or self-reported disease status may influence the results. In addition, residual confounding factors such as physical activity may have influenced the association. Finally, because the number of participants with CVD was very low (1.8%), the study had inadequate statistical power that might explain some of the non-significant findings.

Nevertheless, our study focused on the mediating effects of metabolic factors on CVD and assessed which metabolic factors affect CVD. Our results were produced using the bootstrapping method and did not impose the assumption of normality of the sampling distribution; thus, it was an appropriate design for multiple mediations.16 The given evidence was conceptually approached and was not statistically tested for an indirect effect.

Taken together, our study suggests that diets rich in fruits may contribute to a lower CVD risk partly through lowered SBP. Further prospective studies are needed for confirmation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HAL wrote the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses; DL, KO and EJK, provided advice about writing the manuscript, and HP helped interpret the data.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI13C0729).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ewha Womans University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey files are available from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention database (URL https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/sub03/sub03_02_02.do). If you register your email on this site, you can freely download the raw data.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases Fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/ (accessed 10 Jul 2017).

- 2.Statistics Korea. Causes of death statistics in 2015. http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/8/10/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=357968&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (accessed 10 Jul 2017).

- 3.Feigin VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, et al. Global burden of stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:913–24. 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu D, Zhang X, Gao YT, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of CHD: results from prospective cohort studies of Chinese adults in Shanghai. Br J Nutr 2014;111:353–62. 10.1017/S0007114513002328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aune D, Giovannucci E, Boffetta P, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality-a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1029–56. 10.1093/ije/dyw319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazzano LA. Dietary intake of fruit and vegetables and risk of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeing H, Bechthold A, Bub A, et al. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr 2012;51:637–63. 10.1007/s00394-012-0380-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauchet L, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J. Fruits, vegetables and coronary heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009;6:599–608. 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:69–77. 10.1093/ije/dyt228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DW, Song S, Lee JE, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an FFQ developed for the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1369–77. 10.1017/S1368980014001712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yun SH, Shim J-S, Kweon S, et al. Development of a food frequency questionnaire for the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: data from the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV). Korean J Nutr 2013;46:186–96. (Korean) 10.4163/kjn.2013.46.2.186 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:93–9. 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, Moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40:879–91. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Ezzati M, et al. Metabolic mediators of the effects of body-mass index, overweight, and obesity on coronary heart disease and stroke: a pooled analysis of 97 prospective cohorts with 1·8 million participants. Lancet 2014;383:970–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61836-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du H, Li L, Bennett D, et al. Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1332–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Manson JE, Lee IM, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;72:922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Rimm EB, et al. Mediators of the effect of body mass index on coronary heart disease: decomposing direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology 2015;26:153–62. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Copeland WK, Vedanthan R, et al. Association between body mass index and cardiovascular disease mortality in east Asians and south Asians: pooled analysis of prospective data from the Asia Cohort Consortium. BMJ 2013;347:f5446 10.1136/bmj.f5446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:2287–323. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00128-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Daily vegetable eating among adults, 2013 (or nearest year), in Health at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takachi R, Inoue M, Ishihara J, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of total cancer and cardiovascular disease: Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:59–70. 10.1093/aje/kwm263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019620supp001.pdf (279.8KB, pdf)