Abstract

Objectives

Congenital anomaly (CA) are a leading cause of disease, death and disability for children throughout the world. Many have complex and varying healthcare needs which are not well understood. Our aim was to analyse the healthcare needs of children with CA and examine how that healthcare is delivered.

Design

Secondary analysis of observational data from the Born in Bradford study, a large prospective birth cohort, linked to primary care data and hospital episode statistics. Negative binomial regression with 95% CIs was performed to predict healthcare use. The authors conducted a subanalysis on referrals to specialists using paper medical records for a sample of 400 children.

Setting

Primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare services in a large city in the north of England.

Participants

All children recruited to the birth cohort between March 2007 and December 2011. A total of 706 children with CA and 10 768 without CA were included in the analyses.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Healthcare use for children with and without CA aged 0 to <5 years was the primary outcome measure after adjustment for confounders.

Results

Primary care consultations, use of hospital services and referrals to specialists were higher for children with CA than those without. Children in economically deprived neighbourhoods were more likely to be admitted to hospital than consult primary care. Children with CA had a higher use of hospital services (β 1.48, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.59) than primary care consultations (β 0.24, 95% CI 1.18 to 0.30). Children with higher educated mothers were less likely to consult primary care and hospital services.

Conclusions

Hospital services are most in demand for children with CA, but also for children who were economically deprived whether they had a CA or not. The complex nature of CA in children requires multidisciplinary management and strengthened coordination between primary and secondary care.

Keywords: community child health, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Linking birth cohort data to routine health data produces an enhanced dataset of sociodemographic and clinical information.

Ninety-seven per cent of children from the birth cohort were linked to primary care and hospital episode data.

Data linkage permitted a multiservice, longitudinal evaluation of healthcare use.

We did not have access to electronic referrals; thus, we performed a medical record review to extract this information for a subsample of 400 children.

Introduction

A congenital anomaly (CA) is an abnormality of structure, function or metabolism, present at birth, which may result in mental and physical disability or fatality.1 The incidence of CA in Bradford is high; previously reported at 306 per 10 000 live births, compared with a national average of 227 per 10 000 live births.2 3 Around 93% of children with CA survive to adulthood,2 and a 20-year survival rate is estimated at 85.5% for children born with at least one CA,4 some of whom will have complex conditions requiring multiagency continuing care.5 6 The healthcare needs of children with complex conditions have not been particularly well quantified in the past.7 This may be due in part to a lack of longitudinal data capturing the multidisciplinary care required by children with complex needs.2 In the UK, primary care practice is ideally positioned for monitoring the care requirements of children with complex conditions such as CA, whose prognosis or care needs may change as they develop.2 8–10 Monitoring childhood development across the life course provides invaluable insight into the multidisciplinary care regimes children with complex needs require.11–17 Multidisciplinary care requires the coordination of multiple specialists which may result in late diagnosis leading to reliance on emergency care rather than preventative solutions offered at primary care level, with significant increases in costs.18–22 To represent the multidisciplinary care needs children with CA require, it has been suggested that a combination of primary care consultations, use of hospital services, diagnosis codes, prescribed medications23 and referral information24 produce the best estimates of healthcare use.25 The literature addressing such a comprehensive map of healthcare use for children with CA is limited, with the bulk of evidence coming from American studies investigating hospital use for the treatment of heart CA.18 24–27 Only two studies were found which addressed the demand on primary care services for children with CA.28 29 The need and demand for primary care services in particular are intensified by patient complexity, levels of deprivation and primary care practice provision.16

Our aims were therefore to explore healthcare use longitudinally for children with and without CA from birth up to their fifth birthday (0 to <5). We do this by linking demographic and socioeconomic data from a large prospective birth cohort covering a deprived and ethnically diverse population, to children’s primary care records, hospital episodes statistics and referral information. In doing so, this study examines the effects of having a CA, and consequential ill health, on primary care use, use of hospital services and referrals to multidisciplinary specialists. We also investigate the influence of demographic and socioeconomic factors on healthcare use.

Methods

We used data from the Born in Bradford (BiB) cohort study, an ongoing prospective birth cohort, which recruited 12 450 pregnant women who gave informed consent for the study between 2007 and 2011. It monitors the health of mothers, their partners and birth outcomes for 13 857 children. Detailed information on socioeconomic deprivation, demographics, clinical outcomes and risk factors is recorded. The methods for the BiB study are reported in detail elsewhere.30

Case ascertainment and coding methods

BiB recruits gave their consent for access to electronic primary care records and hospital episode statistics, which are split into elective, accident and emergency (A&E), and other emergency admissions, here referred to as use of hospital services. We linked children’s primary care data held on SystmOne,31 the patient contact single source system which has complete coverage in Bradford, and use of hospital services to BiB questionnaire data.30 Linkage was performed using NHS number, surname, date of birth and gender between SystmOne31 use of hospital services data and BiB. Of 13 857 recruits, 97% were matched to primary care and use of hospital services data, forming the study population. The number of children with at least one (non-birth) hospital event was 5223 (38%). Hospital events included admissions for elective procedures, other emergencies, and A&E presentations. The average time over which data were recorded was 5.5 years, with a maximum of 7.6 years, in all 74 386 person years of data. As not all children in the cohort had reached age 7 years, we censored our follow-up of these cases to age 0 to <5 years.

Primary care data is a trusted source of CA ascertainment, including those diagnosed later in childhood.32 33 We used cross mapping of SystmOne31 diagnostic Clinical Terms Version 3 Read medical codes to International Classification of Diseases version 10 codes (ICD-10)34 to classify and extract children with CA from the primary care database. We followed the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies guidelines, using the British Isles National Organisation of Congenital Anomaly Registers methodology,35 which advise selection of major CA and removal of minor CA. A clinical geneticist reviewed classifications. A total of 860 children with CA were identified, and 154 were excluded, as they had no linked BiB questionnaire data.

Extracting information from paper medical records was necessary to capture multidisciplinary outpatient data and referral activity, as this is sometimes not routinely included in electronic records.36 We extracted referral information from a review of paper medical records using a sample of 200 children with and 200 without CA, selected at random from the BiB cohort. The small sample size was chosen based on the exploratory nature of the medical record review, and the feasibility of performing this by hand within the time scale of this study. A standardised data extraction form was designed, reviewed by a clinician and piloted to accumulate the number and type of referrals to different multidisciplinary services.

Statistical analysis

We had three outcomes for this study. The number of primary care consultations, use of hospital services and referrals to multidisciplinary specialists. Both primary care consultations and use of hospital services were counted as one per day, even if multiple appointments in the same day were recorded, as many of the appointments occurring on the same day were episodes that ran over time, or were duplicates. Negative binomial regression models were used to model primary consultations and use of hospital services as they account for the overdispersion in count data. These models use an exposure variable, which indicates the number of times the event could have happened. Primary care consultations and use of hospital services were expressed per year of observed primary care registered time, which takes into account any periods the child may not have been registered with the primary care practice, withdrawals from the cohort or deaths. We performed a subanalysis reporting regression coefficients for the outcome multidisciplinary referrals.

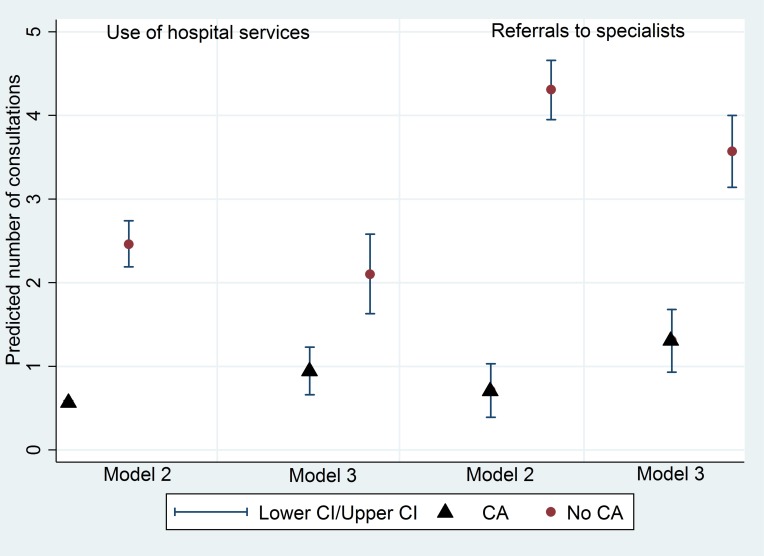

We used three models to compare regression coefficients for each of our three outcomes. Model 1 included univariate analyses, thought of as what is actually observed. Model 2 adjusts for other covariates we determined as confounding factors. Model 3 adjusts for confounders and measures of underlying ill health. Adjusting for ill health using a measure of multimorbidity is a recognised method of risk adjustment for evaluations of healthcare use, as severity of illness may not solely be due to multimorbidity and ill health, it may also be due to other patient characteristics.37 We used a count of unique prescriptions and a count of the number of comorbidities per child as measures of ill health. Simple counts of distinct medications have been suggested as an accurate measure of ill health, given chronic conditions frequently require repeat prescriptions37 38 as have counts of comorbidities in primary care settings.39 40 We performed a test for interaction between whether the child had a CA and level of deprivation for primary care consultations and use of hospital services. We also report the predicted rates of healthcare use for children with and without CA (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Predicted use of hospital services and referrals to multidisaplinary specialists for children with and without CA, before and after controlling for ill health (model 2 adjusted for confounders, model 3 adjusted for confounders and ill health). CA, congenital anomaly.

Confounders

We used directed acyclic graphs to determine the minimally sufficient confounding set for all of our models and checked whether the inclusion of additional covariates improved the model more than would be expected by chance using appropriate model fit statistics. These consisted of maternal age (<20, 20–34, >34 years), educational attainment (low education (<5 GCSE equivalents or other education), high education (5>GCSE equivalents at grades A–C or two advanced level certificates or diploma, degree or higher degree)),41 economic deprivation (economically deprived, not economically deprived (measured using a means-tested benefit status. In the UK, being in receipt of means-tested benefits is recognised as measure of income poverty, as these benefits are frequently the only source of income and are paid at rates that put individuals below standard poverty lines)),42 ethnicity (White British, Pakistani, Other) and consanguinity (non-consanguineous, first cousin, second cousin, other blood (any relation)). All covariates were entered into the model as a categorical variable to allow for possible non-linearity in the relationship between the multimorbidity measure and relevant outcome.

Results

Table 1 shows the characteristics of mothers who gave birth to children with a CA in the BiB cohort (CA=706, no CA=10 768), and average healthcare use up to the child’s fifth birthday. The BiB cohort is multiethnic: 40% white British, 45% Pakistani and 15% ‘other’ ethnicities. Of all children with a CA, 53% were of Pakistani heritage, compared with 35% white British and 13% ‘other’ ethnicities. Forty nine per cent of Pakistani children with CA were from first cousin unions compared with <1% of white British children with CA from first cousin unions. Children of Pakistani heritage with CA had on average 1.61 more primary care consultations, and 0.39 more hospital admissions per year than children without CA. Children with CA of Pakistani heritage had the highest number of primary care appointments over the 5-year period, with on average 2.4 more primary care appointments than children of white British heritage.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort

| All | White British | Pakistani | Other | |||||

| No anomaly | Anomaly | No anomaly | Anomaly | No anomaly | Anomaly | No anomaly | Anomaly | |

| Ethnic origin | 10 768 (93.9%) | 706 (6.2%) | 4288 (94.6%) | 245 (5.4%) | 4804 (92.8%) | 371 (7.2%) | 1653 (94.8%) | 90 (5.2%) |

| Economic deprivation | ||||||||

| Economically deprived | 6147 (57.1%) | 444 (62.9%) | 2072 (48.3%) | 116 (47.4%) | 3315 (69.0% | 280 (75.5%) | 758 (45.9%) | 48 (53.3%) |

| Not economically deprived | 4166 (38.7%) | 247 (35.0%) | 2034 (47.4%) | 122 (49.8%) | 1340 (27.9)% | 85 (22.9%) | 792 (47.9%) | 40 (44.4%) |

| Missing | 455 (4.2%) | 15 (2.1%) | 182 (4.2%) | 7 (2.9%) | 149 (3.1%) | 6 (1.6%) | 103 (6.2%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| Age of mother, years | ||||||||

| 20–34 | 8716 (80.9%) | 554 (78.5%) | 3231 (75.4%) | 180 (73.5%) | 4099 (85.3%) | 312 (84.1%) | 1366 (82.6%) | 62 (68.9%) |

| <20 | 776 (7.2%) | 51 (7.2%) | 536 (12.5%) | 29 (11.8%) | 148 (3.1%) | 15 (4.0%) | 92 (5.6%) | 7 (7.8%) |

| >34 | 1276 (11.9%) | 101 (14.3%) | 521 (12.2%) | 36 (14.7%) | 557 (11.6) | 44 (11.9%) | 195 (11.8%) | 21 (23.3%) |

| Consanguinity | ||||||||

| Non-consanguineous | 7850 (72.9%) | 424 (60.1%) | 4284 (99.8%) | 224 (99.6%) | 2008 (41.8%) | 102 (27.5%) | 1538 (93.0%) | 78 (86.7%) |

| First cousin | 1834 (17.0%) | 192 (27.2%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1753 (36.5%) | 183 (49.3%) | 79 (4.8%) | 8 (8.9%) |

| Second cousin | 637 (5.9%) | 55 (7.8%) | 0 | 0 | 611 (12.7%) | 51 (13.8%) | 25 (1.5%) | 4 (4.4%) |

| Other blood | 447 (4.2%) | 35 (5.0%) | 3 (<1%) | 0 | 432 (9.0%) | 35 (9.4%) | 11 (0.7%) | 0 |

| Maternal education | ||||||||

| Lower education | 2894 (26.9%) | 217 (30.7% | 1228 (28.6%) | 74 (30.2%) | 1374 (28.6%) | 123 (33.2%) | 286 (17.3%) | 20 (22.2%) |

| Higher education | 7617 (70.7%) | 470 (66.6%) | 3014 (70.3%) | 167 (68.2%) | 3357 (69.9%) | 243 (65.5%) | 1223 (74.6%) | 60 (66.7%) |

| Healthcare use | ||||||||

| Average number of primary care consultations per year | 5.21 | 6.82 | 4.21 | 5.49 | 6.20 | 7.89 | 4.91 | 6.01 |

| Average number of admissions per year | 0.11 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.08 | 0.60 |

Children with CA of Pakistani heritage and ‘other ethnicities’ had the same use of hospital services on average, but this was almost double for children with CA of white British heritage (table 1). Table 2 reports the regression coefficients for the univariate and multivariable analysis of primary care and use of hospital services. Sixty-three per cent of children with CA were born into economically deprived neighbourhoods (table 1). Both the adjusted and unadjusted rates suggest that children from economically deprived neighbourhoods have an increased use of hospital services (β 0.35, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.42), but do not use more primary care consultations. Although the most common reason for use of hospital services for children with and without CA was respiratory conditions, when stratified by admission type, children with CA had the most ‘other emergency’ admissions overall (40%), followed by elective admissions (34%), whereas children without CA had an increase of ‘Accident & Emergency’ (49%) admissions (table 3). Diagnoses on admission were also different between groups, with neoplasms and clinical lab findings recorded as the most common reason for admission for children with CA, not recorded in children without CA (table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable coefficients for primary care consultations, use of hospital services and referrals to specialists adjusted for demographic and lifestyle factors in the Born in Bradford cohort

| Outcome 1: primary care consultation rates | Outcome 2: admission rates | Outcome 3: referrals | ||||||||||

| Model 1: univariate | Model 2: multivariate | Model 1: univariate | Model 2: multivariate | Model 1: univariate | Model 2: multivariate | |||||||

| Coefficient | P | Coefficient | P | Coefficient | P | Coefficient | P | Coefficient | P | Coefficient | P | |

| (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | (95% CI) | |||||||

| Economic deprivation | ||||||||||||

| Not economically deprived | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Economically deprived | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.14) | <0.0001 | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.48 | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.42) | <0.0001 | 0.21 (0.13 to 0.29) | <0.0001 | 0.95 (0.35 to 1.56) | 0.002 | 0.55 (0.01 to 1.09) | 0.045 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| White British | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pakistani | 0.43 (0.40 to 0.46) | <0.0001 | 0.40 (0.36 to 0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.27 (0.19 to 0.35) | <0.0001 | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.07) | 0.64 | 0.72 (0.09 to 1.36) | 0.003 | −0.28 (−0.95 to 0.40) | 0.42 |

| Other | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.29) | <0.0001 | 0.26 (0.21 to 0.30) | <0.0001 | −0.08 (−0.19 to 0.03) | 0.15 | −0.14 (−0.25 to −0.03) | 0.02 | −0.03 (−0.92 to 0.85) | 0.94 | −0.36 (−1.11 to 0.39) | 0.35 |

| Mother’s age, years | ||||||||||||

| 20–34 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| <20 | −0.13 (−0.19 to −0.07) | <0.0001 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.04) | 0.68 | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.24) | 0.13 | 0.07 (−0.07 to −0.21) | 0.32 | −0.31 (−1.39 to 0.77) | 0.58 | −0.42 (−1.32 to 0.48) | 0.36 |

| >34 | −0.06 (−0.10 to −0.01) | <0.02 | −0.03 (−0.08 to 0.01) | 0.13 | −0.15 (−0.27 to −0.04) | 0.01 | −0.17 (−0.28 to −0.06) | 0.002 | 0.83 (−0.08 to 1.74) | 0.07 | 0.64 (−0.10 to 1.38) | 0.09 |

| Consanguinity | ||||||||||||

| Non-consanguineous | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| First cousin | 0.29 (0.25 to 0.32) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.08) | 0.17 | 0.48 (0.39 to 0.58) | <0.0001 | 0.28 (0.17 to 0.39) | <0.0001 | 1.19 (0.48 to 1.91) | 0.001 | 0.24 (−0.50 to 0.97) | 0.53 |

| Second cousin | 0.24 (0.18 to 0.30) | <0.0001 | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.05) | 0.78 | 0.24 (0.09 to 0.39) | 0.002 | −0.01 (−0.17 to −0.15) | 0.94 | 1.17 (0.11 to 2.23) | 0.031 | 0.26 (−0.70 to 1.21) | 0.59 |

| Other blood | 0.25 (0.18 to 0.32) | <0.0001 | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.05) | 0.86 | 0.31 (0.14 to 0.48) | <0.0001 | 0.23 (0.05 to −0.41) | 0.012 | −0.03 (−1.54 to 1.48) | 0.96 | −0.32 (−1.60 to 0.97) | 0.63 |

| Congenital anomaly | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 0.29 (0.23 to 0.35) | <0.0001 | 0.24 (1.18 to 0.30) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.35 to 1.57) | <0.0001 | 1.48 (1.36 to 1.59) | <0.0001 | 3.71 (3.28 to 4.15) | <0.0001 | 3.59 (3.11 to 4.08) | <0.0001 |

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Maternal education | ||||||||||||

| Lower education | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Higher education | −0.04 (−0.08 to −0.01) | 0.007 | −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.003) | 0.031 | −0.21 (−0.29 to −0.13) | <0.0001 | −0.09 (−0.17 to −0.01) | 0.021 | −0.70 (−1.34 to −0.06) | 0.032 | 0.06 (−0.49 to 0.61) | 0.83 |

Table 3.

Proportion of admissions by type and most common reason for admission

| Admittance type | Total number of admissions over a period of 5 years | Most common reason for admission | ||

| No anomaly | Anomaly | No anomaly | Anomaly | |

| Accident and emergency | 3985 (49%) | 609 (26%) | 1. Respiratory 2. Injury/poison |

1. Respiratory 2. Infectious parasitic |

| Other emergency | 2522 (31%) | 932 (40%) | 1. Respiratory 2. Infectious parasitic |

1. Respiratory 2. Clinical lab findings |

| Elective | 1632 (20%) | 801 (34%) | 1. Eye/ear 2. Respiratory |

1. Neoplasms/blood/immune 2. Congenital abnormalities |

Reasons for admission derived from ICD-10 codes at patient discharge, using ICD-10 groupings to categorise35

Children from both Pakistani heritage and other ethnicities were predicted to require an increase in primary care consultations in both the univariate and multivariable analyses. Children who had older mothers (>34) were predicted to use hospital services less (β −0.17, 95% CI −0.28 to –0.06), but not primary care consultations (β −0.03, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.01) after adjustment for confounders. Children born into consanguineous families were predicted to have an increased use of hospital services, but not primary care consultations. Children with a CA had the largest increase in use of primary care consultations (β 0.24, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.30) and use of hospital services (β 1.48, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.59) after adjustment for confounders, for which usage was almost three times higher. Higher maternal education reduced primary care consultations and use of hospital services (table 2). The subanalysis of multidisciplinary referrals predicts an increased use of specialist referrals for children with CA after adjustment for confounders (β 3.59, 95% CI 3.11 to 4.08). The only other marginally significant factor was children born into economically deprived neighbourhoods (β 0.55, 95% CI 0.01 to 1.09). We adjusted for ill health for services with the highest predicted usage, those being hospital services and multidisciplinary referrals for children with and without CA (figure 1). After controlling for ill health, the predicted increased use of hospital services for children with CA reduces by almost half but still remains (β 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.97), as does the predicted increased use of multidisciplinary referrals (β 2.27, 95% CI 1.59 to 2.94) (figure 1).

From a possible 41 different specialists, the most common referral was to consultant paediatricians (14% 59/400), followed by neonatology (13% 57/400), paediatric surgery (8% 34/400) and local cardiology services (7% 30/400). On average, children had between three and four specialists involved in their care simultaneously.

Interactions

Interaction effects between whether the child had a CA and economic deprivation were not significant in multivariable models.

Discussion

Our data suggest that children with CA have higher numbers of primary care consultations, admissions to hospital and referrals to multidisciplinary specialists on average per year than children without CA. This finding is perhaps not surprising, but is now quantified. Children of Pakistani heritage have almost double the number of hospital admissions per year than children of white British heritage. Children with CA were predicted to require an increase in primary care consultations and hospital services compared with children without a CA. We found only one study reporting an increase in primary care consultations for children with CA, but heart CA specifically.28 Although we find that children from Pakistani heritage are predicted to use more primary care consultations than children without CA, this might be explained by more than half (53%) of children with CA in the BiB cohort being of Pakistani heritage (53%). When stratifying the analysis by CA, we also find that children with CA from economically deprived neighbourhoods have an increased risk of using hospital services, but not primary care consultations. This might be explained by previous findings from the BiB cohort suggesting that mothers from poorer backgrounds are less likely to use primary care services due to variation in primary care practice provision.43

Our data suggest that the use of hospital services are in higher demand than primary care consultations. Although an increased use of hospital services can be expected for children with CA,14 24 26–28 we find that the type of hospital admission differs between children with and without CA. This is most likely explained by CA requiring more intensive treatment. For example, although respiratory conditions were the most common reason for using hospital services overall (table 3), a finding similar to other studies,27 ‘other emergency’ admissions were the most frequently used hospital service for children with CA. Other emergency refers to urgent referrals requiring corrective and sometimes surgical interventions that are initiated by health professionals, rather than parents presenting with their child at A&E. This increase in other emergency and elective procedures is a finding similar to that of other CA studies.14 29

Children with a CA were predicted to require more referrals to multidisaplinary specialists than children without CA, and have more than one specialist involved in their care simultaneously compared with children without CA. Although patient complexity increases the need for healthcare,16 coordination of appointments for the multiple specialists required is also susceptible to variation, and is sometimes exacerbated by the divide between primary care, community and hospital services,2 which is also associated with patient complications, late diagnosis and an increased reliance on emergency care.18 This suggests that although the predicted increase in use of hospital services for children with CA may be primarily due to their complex needs and ill health, there may be scope for this to be reduced through increasing the efficiency of care coordination.44 In terms of clinical implications, our findings provide the quantified, longitudinal evidence requested by the Chief Medical Officer, supporting the suggestion of key workers as a catalyst for efficient patient navigation through services.3 Also, when adjusting for ill health, the predicted increase in use of hospital services and multidisciplinary referrals for children with CA reduces (figure 1), suggesting higher usage may not be completely attributable to ill health, but affected by other factors such as deprivation and ethnicity.

There are limitations. Using a subset of diseases (CA) does not cover all children with conditions that may also be complex; however, in order to extract a population we could be sure were both representative of complexity, and prevalent enough to create sample size groups large enough for comparison, CA were chosen based on the knowledge that they are high in numbers in Bradford and known to require complex care.45 These results are based on the Bradford population, which might be interpreted as a limitation in terms of generalisability. However, we feel that these results are applicable to other populations or NHS trusts serving highly deprived and ethnically diverse groups of patients, characteristics which are known to be associated with CA.45 Despite the successful linkage of primary care to cohort data in this study (97%), attributable to the complete SystmOne coverage of primary care practices in Bradford, the use of paper medical records for capturing referral activity is susceptible to missed information due to fluctuations in consultant record keeping, interpreting handwritten entries and missing records. This research therefore illustrates the potential advantages of implementing a completely ‘paperless’ record keeping ethos, and the future emphasis for ensuring the exchange of data between IT systems in all clinical and care settings. This will only further strengthen the interpretability of key information at the point of care for patients with complex healthcare needs.46

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who took part in the Born in Bradford study, the midwives for their help in recruitment, the paediatricians and health visitors, the Born in Bradford team, which included interviewers, data managers, laboratory staff, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers and managers.

Footnotes

Contributors: CFB and BK had full access to all the data, and conducted the analysis and statistical interpretation. RP and NS contributed to the conception and design of the work, and drafting and critical revision for intellectual content. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This paper presents independent research by a PhD candidate supported by a Bradford University studentship, in conjunction with the White Rose Consortium, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Yorkshire and Humber programme ’Healthy Children Healthy Families Theme', IS-CLA-0113-10020.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The sponsors of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, or writing of the report.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval for the cohort study was provided by Bradford Local Research Ethics Committee (reference 06/Q1202/48).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Misra T, Dattani N, Majeed A. Congenital anomaly surveillance in England and Wales. Public Health 2006;120:256–64. 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2012: Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays. 2013. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chief-medical-officers-annual-report-2012-our-children-deserve-better-prevention-pays (accessed 31 Oct 2016).

- 3.Congenital Anomaly Statistics 2012. British Isles Network of Congenital Anomaly Registers. 2014. http://www.binocar.org/content/Annual%20report%202012_FINAL_nologo.pdf.

- 4.Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, et al. 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: a population-based study. Lancet 2010;375:649–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61922-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NHS. Five-year forward review, 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 8 Jun 2017).

- 6.Department of Health. National framework for children and young peoples continuing care. London: Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Children with special educational and complex needs. Guidance for Health and Wellbeing Boards. London: Department of health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooley WC. Responding to the developmental consequences of genetic conditions: the importance of pediatric primary care. Am J Med Genet 1999;89:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starfield B, et al. Primary care and genetic services: Health care in evolution. Eur J Public Health 2002;12:51–6. 10.1093/eurpub/12.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinke ML, Driscoll A, Mikat-Stevens N, et al. A Quality Improvement Collaborative to Improve Pediatric Primary Care Genetic Services. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20143874 10.1542/peds.2014-3874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colvin L, Bower C. A retrospective population-based study of childhood hospital admissions with record linkage to a birth defects registry. BMC Pediatr 2009;9:32 10.1186/1471-2431-9-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, et al. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics 2009;123:407–12. 10.1542/peds.2007-2875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diederichs C, Berger K, Bartels DB. The measurement of multiple chronic diseases--a systematic review on existing multimorbidity indices. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:301–11. 10.1093/gerona/glq208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polita NB, Ferrari RA, de Moraes PS, et al. Congenital anomalies: hospitalization in a pediatric unit. Rev Paul Pediatr 2013;31:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong W, Finnie DM, Shah ND, et al. Effect of multiple chronic diseases on health care expenditures in childhood. J Prim Care Community Health 2015;6:2–9. 10.1177/2150131914540916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Kings Fund. 2016 Understanding Pressures in General Practice. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf (accessed 6 Apr 2017).

- 17.Shetty S, Kennea N, Desai P, et al. Length of stay and cost analysis of neonates undergoing surgery at a tertiary neonatal unit in England. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016;98:56–60. 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson C, Dawson A, Grosse SD, et al. Hospitalizations, costs, and mortality among infants with critical congenital heart disease: how important is timely detection? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2013;97:664–72. 10.1002/bdra.23165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavroudis CD, Mavroudis C, Jacobs JP. The elephant in the room: ethical issues associated with rare and expensive medical conditions. Cardiol Young 2015;25:1621–5. 10.1017/S1047951115002103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rare Diseases UK. The national alliance for all those with a rare disease and those that support them. Report of activity. 2015. https://www.raredisease.org.uk/media/1862/rduk-activity-report-2015-final.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2016).

- 21.Luthy SK, Yu S, Donohue JE, et al. Parental Preferences Regarding Outpatient Management of Children with Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatr Cardiol 2016;37:151–9. 10.1007/s00246-015-1257-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genetic Alliance UK. The Hidden Costs of Rare Diseases. 2016. http://www.geneticalliance.org.uk/media/2502/hidden-costs-full-report_21916-v2-1.pdf (accessed 3 Jun 2017).

- 23.Crooks CJ, West J, Card TR. A comparison of the recording of comorbidity in primary and secondary care by using the Charlson Index to predict short-term and long-term survival in a routine linked data cohort. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007974 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawson AL, Cassell CH, Oster ME, et al. Hospitalizations and associated costs in a population-based study of children with Down syndrome born in Florida. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2014;100:826–36. 10.1002/bdra.23295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquali SK, He X, Jacobs ML, et al. Excess costs associated with complications and prolonged length of stay after congenital heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1660–6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simeone RM, Oster ME, Hobbs CA, et al. Population-based study of hospital costs for hospitalizations of infants, children, and adults with a congenital heart defect, Arkansas 2006 to 2011. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2015;103:814–20. 10.1002/bdra.23379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal S, Sud K, Menon V. Nationwide Hospitalization Trends in Adult Congenital Heart Disease Across 2003-2012. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5:19 10.1161/JAHA.115.002330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billett J, Cowie MR, Gatzoulis MA, et al. Comorbidity, healthcare utilisation and process of care measures in patients with congenital heart disease in the UK: cross-sectional, population-based study with case-control analysis. Heart 2008;94:1194–9. 10.1136/hrt.2007.122671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood R, Wilson P. General practitioner provision of preventive child health care: analysis of routine consultation data. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:73 10.1186/1471-2296-13-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright J, Small N, Raynor P, et al. Cohort Profile: the Born in Bradford multi-ethnic family cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:978–91. 10.1093/ije/dys112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SystmOne. The Pheonix Partnership (TPP). 2016. https://www.tpp-uk.com/products/systmone (accessed 13 Mar 2017).

- 32.Charlton RA, Weil JG, Cunnington MC, et al. Identifying major congenital malformations in the UK General Practice Research Database (GPRD): a study reporting on the sensitivity and added value of photocopied medical records and free text in the GPRD. Drug Saf 2010;33:741–50. 10.2165/11536820-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sokal R, Fleming KM, Tata LJ. Potential of general practice data for congenital anomaly research: comparison with registry data in the United Kingdom. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2013;97:546–53. 10.1002/bdra.23150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC). Hospital Episode Statistics. Hospital outpatient activity. Leeds: Health & Social Care Informtion Centre, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.EUROCAT. EUROCAT Guide 1.4: Instruction for the registration of congenital anomalies. Ulster: EUROCAT Central Registry, University of Ulster, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassar M, Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2013;10:12–5937. 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Mourik MS, Moons KG, Murphy MV, et al. Severity of disease estimation and risk-adjustment for comparison of outcomes in mechanically ventilated patients using electronic routine care data. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:807–15. 10.1017/ice.2015.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brilleman SL, Salisbury C. Comparing measures of multimorbidity to predict outcomes in primary care: a cross sectional study. Fam Pract 2013;30:172–8. 10.1093/fampra/cms060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.France EF, Wyke S, Gunn JM, et al. Multimorbidity in primary care: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:297–307. 10.3399/bjgp12X636146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, et al. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:134–41. 10.1370/afm.1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Department for Education. GCSE subject content, 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/gcse-subject-content (accessed 26 Oct 2017).

- 42.Platt L. Poverty and Ethnicity in the UK. Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelly B, Mason D, Petherick ES, et al. Maternal health inequalities and GP provision: investigating variation in consultation rates for women in the Born in Bradford cohort. J Public Health 2017;39:1–8. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solberg LI. Care coordination: what is it, what are its effects and can it be sustained? Fam Pract 2011;28:469–70. 10.1093/fampra/cmr071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheridan E, Wright J, Small N, et al. Risk factors for congenital anomaly in a multiethnic birth cohort: an analysis of the Born in Bradford study. Lancet 2013;382:1350–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61132-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Digital NHS. A common vocabulary to reduce GP burden and improve patient care. 2017. https://digital.nhs.uk/article/930/A-common-vocabulary-to-reduce-GP-burden-and-improve-patient-care- (accessed 9 Jun 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.