Abstract

Objectives

To examine and compare the prevalence of coronary artery calcification (CAC) and the frequency of cardiac events in a background population and a cohort of patients with non-specific chest pain (NSCP) who present to an emergency or cardiology department and are discharged without an obvious reason for their symptom.

Design

A double-blinded, prospective, observational cohort study that measures both CT-determined CAC scores and cardiac events after 1 year of follow-up.

Setting

Emergency and cardiology departments in the Region of Southern Denmark.

Subjects

In total, 229 patients with NSCP were compared with 722 patients from a background comparator population.

Main outcomes measures

Prevalence of CAC and incidence of unstable angina (UAP), acute myocardial infarction (MI), ventricular tachycardia (VT), coronary revascularisation and cardiac-related mortality 1 year after index contact.

Results

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of CAC (OR 0.9 (95% CI 0.6 to 1.3), P=0.546) or the frequency of cardiac endpoints (P=0.64) between the studied groups. When compared with the background population, the OR for patients with NSCP for a CAC >100 Agatston units (AU) was 1.0 (95% CI 0.6 to 1.5), P=0.826. During 1 year of follow-up, two (0.9%) patients with NSCP underwent cardiac revascularisation, while none experienced UAP, MI, VT or death. In the background population, four (0.6%) participants experienced a clinical cardiac endpoint; two had an MI, one had VT and one had a cardiac-related death.

Conclusion

The prevalence of CAC (CAC >0 AU) among patients with NSCP is comparable to a background population and there is a low risk of a cardiac event in the first year after discharge. A CAC study does not provide notable clinical utility for risk-stratifying patients with NSCP.

Trial registration number

NCT02422316; Pre-results.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, coronary intervention, ischaemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, cardiovascular imaging, computed tomography

Strength and limitations of this study.

The patients were unselected.

The patients were included from six hospitals.

The number of participants was relatively small.

No patients were lost to follow-up.

Few events occurred during follow-up.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major public health problem and the most common cause of death among men and women in Europe and the USA.1–3 Less than one in five patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain have acute myocardial infarction (MI).4 5 Other potential causes for their symptoms include non-ischaemic cardiac disease (aneurysm, aortic dissection or pulmonary embolism) and non-cardiac disease (respiratory, gastrointestinal or musculoskeletal disorders). However, for a significant number of patients the cause of symptoms is unclear and such patients are defined as having non-specific chest pain (NSCP).6 For these patients, the exclusion of acute MI in an acute care setting does not rule out underlying coronary artery disease (CAD) or the associated risk of future cardiac events, as demonstrated by studies showing that 0.8%–2.1% of patients evaluated for MI and discharged from emergency departments have an adverse cardiac outcome in the first 30 days after discharge.7 8

Up to 20% of patients with CAD do not have the traditional CVD risk factors of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes or smoking.9 Consequently, there is a need to identify diagnostic tools that can be used to risk-stratifying patients with chest pain, particularly in an acute care setting. A non-contrast cardiac CT can be used to measure the presence and extent of coronary artery calcification (CAC) and might serve as one such tool. As a diagnostic test, it offers the advantages of easy performance, simple interpretation and high reproducibility, while exposing patients to relatively low levels of radiation.10–13 While it has been evaluated as a risk stratification tool in asymptomatic individuals, and demonstrated a CAC prevalence of 44%–50%,14 15 its role in patients with NSCP remains uninvestigated.

In order to evaluate the role of non-contrast cardiac CT as a risk stratification tool for patients with NSCP, this study had two goals. The first was to identify the prevalence of CAC among patients with NSCP discharged from emergency and cardiology departments, and compare these findings with observations from an asymptomatic background population. The second was to examine the frequency of clinical cardiac events in patients with NSCP during a 12-month follow-up period and compare that data with results from an asymptomatic background population and from a population of higher-risk patients with NSCP who are referred for further cardiac testing after index contact.

Method and materials

Study design

The study was a double-blinded, prospective, observational cohort study. It included patients from emergency and cardiology departments in the Region of Southern Denmark, specifically in the cities of Odense, Svendborg, Vejle, Kolding, Aabenraa and Sonderborg. Patients were enrolled between September 2014 and May 2015 provided they met the following inclusion criteria: they presented to hospital with acute chest pain and a suspicion of cardiac ischaemia; they were admitted to hospital; they had at least one troponin measurement; they were discharged with a diagnosis of observation for MI or chest pain (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision codes: DR072/DR073/DR034/DR035); and there was no identifiable cause for their chest pain. An additional inclusion criterion was the presence of at least one known risk factor for CAD (current smoker, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus or significant family history of CVD).

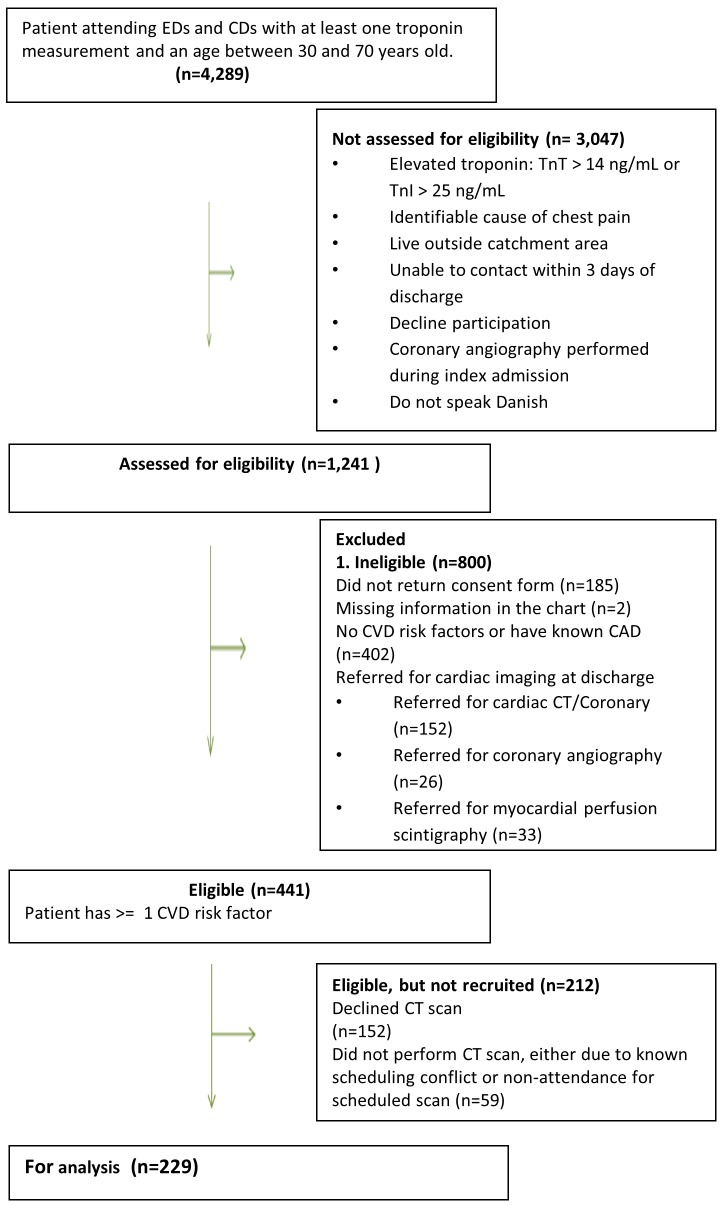

Patients were excluded from the study if they were referred for outpatient cardiac imaging test after the index visit, lived outside the catchment area (Region of Southern Denmark), were unable to speak Danish, declined to either complete a telephone interview and/or undergo a CT scan, or had a previous history of CAD as defined by previous MI or coronary revascularisation (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the inclusion of patients with non-specific chest pain. CAD, coronary artery disease; CD, cardiology department; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ED, emergency department.

Study population

The study population was identified by performing a daily search of troponin values in the central biochemical laboratory, which stores results for the Region of Southern Denmark. Electronic patient files for any emergency or cardiology department patients between the ages of 30 years and 70 years were reviewed, and patients with normal troponin values, as defined by a high sensitivity troponin T ≤14 ng/L or a high sensitivity troponin I <25 ng/L, were assessed for study eligibility. Provided they met eligibility criteria, they completed a structured telephone questionnaire within 3 days of discharge from index contact. Thereafter, consent forms and study information were sent out. Those patients who returned the consent form were scheduled for a non-contrast CT scan, the results of which were blinded to participants and investigators until the conclusion of the study.

For comparison purposes, we used the Danish Risk Score study (DanRisk) population15 as a background comparator group. The DanRisk study population included 1257 asymptomatic subjects, aged 50–60 years, who were examined in one of four cardiac CT centres in the Region of Southern Denmark (Odense, Esbjerg, Vejle or Svendborg). From this study population, we excluded asymptomatic individuals without risk factors for CAD (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, familiar disposition, known smoker and diabetes mellitus), individuals with known CAD and those missing CAC scores. The remaining group of individuals comprised the comparator group.

Definitions

Comorbidity in the NSCP population was self-reported. Individuals were considered to have diabetes mellitus if they used an antidiabetic medication or had been given a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus by their general practitioner. Similarly, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia were considered present if participants used medications to treat either disease or if they had received a diagnosis of either illness. Family history was defined as a first-degree relative with CVD regardless of age of onset, while smoking was defined by current smoking status. The first blood pressure and heart rate values taken during the index admission were retrieved from patient files. Cholesterol values were collected up to 3 months before and 3 months after the index admission, with the value closest to the index date selected for the study. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on self-reported height and weight.

In the background comparator group, individuals were considered to have diabetes mellitus, hypertension or hypercholesterolaemia if they used an antidiabetic, hypertension or cholesterol-lowering medication, respectively. Family history was defined by the presence of CVD in a male first-degree relative <55 years or a female first-degree relative <65 years. Smoking was based on smoking status at the time the study was conducted. Blood pressure, heart rate, BMI and cholesterol values were measured during baseline examination.

Troponins

Troponin I, used by Odense University Hospital, was analysed using the Abbot Diagnostics Architect with an upper reference limit of 99th percentile for 24 ng/L and a coefficient variation of <10% at 5 ng/L. The decision limit for MI was set at ≥25 ng/L.

Troponin T, used by the other participating hospitals, was analysed by Roche Diagnostic Elecsys 2010, modular analytics E170, Cobas e411 and Cobas e601. The 99th percentile upper reference limit was 14 ng/L, with a coefficient variation of <10% at 13 ng/L and a decision limit for MI set at >14 ng/L.

Cardiac CT protocol

CAC was measured by summing the scores for calcific foci in the coronary arteries and then expressing the total calcium burden in Agatston units (AU).10 CAC was assessed by trained radiographers. In an additional 52 subjects, the CAC score was reanalysed by the first author.

Two centres used a dual-source CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany) with prospective ECG triggering. In participants with a heart rate <75 beats per minute (bpm), ECG triggering was set during the diastolic phase at 65%–75% of the cardiac R–R interval, while in persons with a heart rate ≥75 bpm ECG triggering was set during the systolic phase at 250–400 ms. Additional CT settings included the following: sequential prospective scan, slice thickness 3 mm, collimation 128×0.6 mm, gantry rotation time 0.28 ms, 120 kV tube voltage and 90 mAs/rotation.

One centre used a GE 64-slice CT scanner (Discovery 750 HD; GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA). In individuals with heart rates <75 bpm, ECG triggering was set in diastolic phase at 75% of the cardiac R–R interval, and in those with heart rates ≥75 bpm, it was set in the systolic phase at 40% of the cardiac R–R interval. Other settings in this centre included: sequential prospective scan, slice thickness 2.5 mm, collimation 64×0.625 mm, gantry rotation time 0.35 ms, 120 kV tube voltage and a 200 mA tube current.

Finally, one centre used a Toshiba Aquillion ONE CT scanner (Toshiba Medical systems, Japan) with prospective ECG triggering. If the heart rate was <75 bpm, then ECG triggering was in the diastolic phase at 65%–75% of the R–R interval and if the heart rate was ≥75 bpm, then ECG triggering was set in the systolic phase at 40%. Additional settings were: sequential prospective scan, slice thickness 0.5 mm, collimation 0.5 mm×240–320, gantry rotation time 0.275 ms and 120 kV tube voltage.

Follow-up

The study was double blinded with a 12-month follow-up. Neither participants nor investigators knew the results of the CAC score until the end of follow-up, at which time participants and their general practitioner received a letter with the results of testing.

The clinical endpoints at follow-up were unstable angina (UAP), non-fatal MI, ventricular tachycardia (VT), coronary revascularisation and cardiac death. The endpoints were compared with the control population and with NSCP patients who were referred for cardiac imaging testing at the index admission, but who consequently did not participate in the study.

Sample size

A sample size calculation was performed before the study. The prevalence of an elevated CAC score (CAC >0 AU) in the DanRisk comparator population was 44%.15 We assumed that the prevalence of CAC scores in our symptomatic low-risk population would be 18% higher (or 62%), since previous studies found that 79% of symptomatic individuals referred for coronary angiography have a CAC >0 AU.16 Using the Fleiss method, we calculated that we required a sample size of at least 238 patients if we were to detect a risk factor with an OR of at least 2.1, a significance level of 95%, a power of 80% and a ratio of 1 for exposed/non-exposed.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables are presented with frequency tables and percentages with the distributions of continuous variables evaluated by empirical histograms. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean and SD values, whereas skewed distributed continuous variables are presented with their median and IQR. Fischer’s exact test and the χ2 test were used for categorical variables, a t-test was used to compare normally distributed variables and the Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was used for skewed distributed variables. Patients with NSCP and the control population were compared using a multivariate analysis that included traditional CVD risk factors (gender, age, smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus, a family history of CVD and BMI), the prevalence of CAC (the dependent variable) >0 and CAC ≥100. The correlation coefficient was 99%. Analyses were performed with STATA SE 14. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark (S-20140055) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from participating individuals.

The DanRisk protocol was approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark (S-20080140) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from participating individuals.

Results

In total, there were 4289 patients, aged 30–70 years old, who were seen in either an emergency or cardiology department, and who had at least one troponin measurement. Among these patients, 3047 were not assessed for study eligibility on the basis of one or more criteria (see figure 1). Of the remaining 1241 patients, 800 were assessed for study eligibility, but excluded based on the presence of one or more exclusion criteria. From the residual 441 patients, 229 participated in the study and underwent a cardiac CT scan, while the remaining 212 patients, who were classified as non-participants, either declined study participation or failed to undergo a cardiac CT scan.

Comparing participants with non-participants, it can be seen that the mean age was respectively 57 years (95% CI 56 to 58) and 52 years (95% CI 50 to 53), with a P=0.001. Significantly more participants had hypercholesterolaemia and a family history of CVD compared with non-participants, while no significant differences were found in gender, diabetes, hypertension or smoking status (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants and non-participants

| Participants | Non-participants | P value | |

| N=229 | N=212 | ||

| Age (years) | 57 (56 to 58) |

52 (50 to 53) |

0.001 |

| Male | 98 (43) | 89 (42) | 0.86 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 (10) | 10 (5) | 0.048 |

| Hypertension | 91 (40) | 70 (33) | 0.14 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 97 (42) | 67 (32) | 0.02 |

| Family history | 124 (54) | 93 (44) | 0.03 |

| Smoking | 58 (25) | 57 (27) | 0.71 |

Values are n (%) or mean (95% CI).

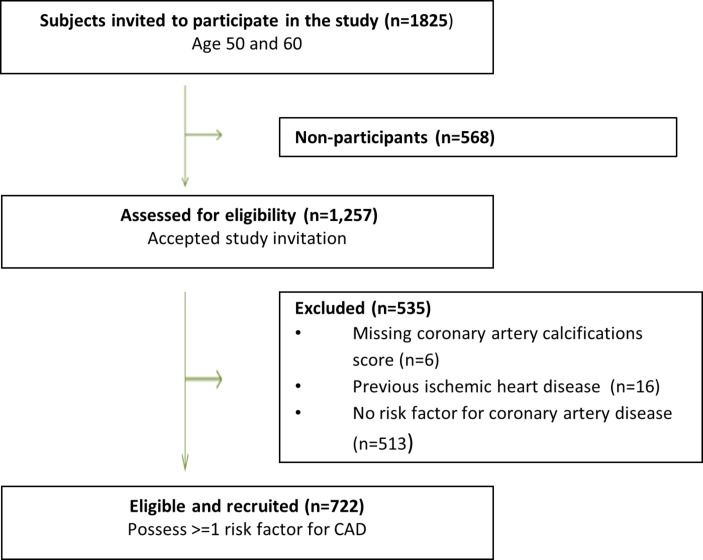

Figure 2 shows the selection of the control group. Of the 1825 randomly selected individuals 50 or 60 years old who were invited to participate in the DanRisk study, there were 1257 who accepted the invitation. Based on the criteria established for this study, a total of 535 individuals were excluded from participation, of whom 513 did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of having at least one risk factor, 16 patients had known CAD and 6 did not have a CAC score. The background comparison group was thus composed of the residual 722 individuals.

Figure 2.

Flow chart for the inclusion of the background population. CAD, coronary artery disease.

Table 2 lists the characteristics of patients with NSCP and the background comparison group. Mean age for the NSCP population was 57 years, compared with 55 years for the DanRisk group (P=0.007). A significantly higher proportion of patients with NSCP had known hypercholesterolaemia and a family history of CVD, while more participants in the comparison group were smokers. Furthermore, significant differences were found between the populations with respect to blood pressure, heart rate and total cholesterol.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of patients with non-specific chest pain and the background population

| Patients with NSCP | Background population | P value | |

| N=229 | N=722 | ||

| Male | 98 (43) | 295 (45) | 0.48 |

| Age (years) | 57±9 | 55±5 | 0.008 |

| 30–39 | 7 (3) | – | 0.001 |

| 40–49 | 46 (20) | – | |

| 50–59 | 76 (33) | 316 (44) | |

| 60–70 | 100 (44) | 406 (56) | |

| Hypertension | 91 (40) | 266 (37) | 0.460 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 97 (42) | 126 (18) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 22 (10) | 59 (8) | 0.51 |

| Family history of CVD | 124 (54) | 287 (40) | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 58 (25) | 314 (44) | 0.001 |

| Previous smoker | 74 (32) | 197 (27) | 0.142 |

| Non-smoker | 97 (42) | 211 (29) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 144±30 | 137±19 | 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 97±122 | 83±10 | 0.002 |

| Heart rate | 74±14 | 71±14 | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2±1.1 | 5.5±1.1 | 0.005 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.1±0.9 | 3.2±0.9 | 0.070 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.4±0.5 | 1.5±0.5 | 0.080 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27±6 | 27±5 | 0.715 |

| CAC score (AU) | 2 (0–74) | 1 (0–54) | 0.229 |

| 0 | 106 (46) | 350 (48) | 0.679 |

| 1–99 | 74 (32) | 238 (33) | 0.897 |

| ≥100 | 49 (22) | 134 (19) | 0.438 |

Values are n (%), mean±SD or median (IQR).

AU, Agatston unit; BMI, body mass index; CAC, coronary artery calcification; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; NSCP, non-specific chest pain.

The prevalence of the CAC score categories (0 AU, 1–99 AU, ≥100 AU) were similar for the NSCP and background population (46%, 32%, 22% vs 48%, 33% and 19%, P=0.630), and there was no difference in the median CAC score (2 AU (IQR 0–74 AU) and 1 AU (IQR 0–54 AU), P=0.229). We analysed various subgroups, and there were similarly no differences in the median CAC scores for women (0 AU (IQR 0–67 AU) and 0 AU (IQR 0–18 AU), P=0.74), men (18 AU (IQR 0–83 AU) and 9 AU (IQR 0–116 AU), P=0.12) or 50–59 year olds (0 AU (IQR 0–33 AU) and 0 AU (IQR 0–12.5 AU), P=0.25). However, the subgroup of 60–69 year olds had a higher median CAC score in the NSCP group compared with the background population (47 AU (IQR 0–147 AU) vs 7 AU (IQR 0–110 AU), P=0.008). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis there was no significant difference in CAC in the NSCP and background population (OR 0.9 (95% CI 0.6 to 1.3), P=0.546). The OR for CAC >100 AU was 1.0 (95% CI 0.6 to 1.5) P=0.826 (online supplementary tables). In 52 cases, two independent readers performed the CAC score measurement; the Pearson’s correlation was 99%.

bmjopen-2017-018391supp001.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)

During 1 year of follow-up, 2 out of 229 patients with NSCP underwent cardiac revascularisation, while none had UAP, MI, VT or death related to cardiac causes. Of the two patients who underwent cardiac revascularisation, one was a woman aged 64 years with a CAC score of 340, and the other patient was a male aged 60 years with a CAC score of 2595. Both were known to have hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and a significant family history of CVD. The event rate in the background population was 4 out of 722, with all of the involved patients were male: two had an MI, one had VT and one had a cardiac-related death. The patient with VT was 50 years old and had a CAC=0, but a significant family history of CVD. The three remaining patients were 60 years old with CAC scores of 166, 832 and 1326. One patient was a smoker with hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, while a second was a smoker with diabetes and a family history of CVD. Fisher’s exact test showed no statistically difference in the incidence of endpoints between NSCP and the background population (0.9% (95% CI 0.1 to 2.9) vs 0.6% (95% CI 0.2 to 1.3), P=0.64).

A further 211 patients were referred for cardiac testing at the time of index contact and were not included in this study. Of those, 152 had a cardiac CT, 26 were referred for coronary angiography and 33 for myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. After 1 year of follow-up, two of these patients had UAP, two had an MI and nine had coronary revascularisation. No one had VT or died from cardiac-related causes. In total, 11 out of 211 patients (5.2% (95% CI 2.8 to 8.9)) had an event, a rate that was significantly higher compared with the NSCP and background populations (P=0.001).

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge to evaluate the role of non-contrast CT in an NSCP population.

We demonstrated that CAC can be detected in approximately half of patients with NSCP, a prevalence that does not differ significantly from what can be found in the general population. Furthermore, the prognosis for patients with NSCP does not differ from the prognosis in an asymptomatic background population. However, a comparison of patients with NSCP and a background population with those referred for cardiac investigation showed that the latter group has a significantly higher rate of clinical events. As the CAC score in patients with NSCP does not differ from the general population, we do not consider non-contrast CT scanning a useful risk stratification tool for patients with NSCP. It appears to be of limited value for patients with NSCP, and moreover may lead to increased downstream test utilisation.

Laudon et al17 showed that in patients with non-cardiac chest pain presenting to the emergency department and fulfilling the criteria for UAP, the prevalence of CAC is 49%, which is consistent with our findings in patients with NSCP. In Laudon’s study, patients with non-cardiac chest pain with a CAC=0 had a 100% 5 year probability of event-free survival. This was significantly better than for the cardiac-related chest pain group, which implies that a non-contrast CT scan may be useful in discriminating between non-cardiac-related and cardiac-related chest pain. However, the study by Laudon et al included patients fulfilling the criteria for unstable angina, who were scanned during the index contact. Thus, this patient population was at higher risk of CVD compared with the patients in our study, who were not referred for further cardiac investigations after the index contact.

The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines recommends referring patients for a coronary CT angiography (which also visualises the arterial lumen), if they present to the emergency department with acute chest pain, a negative ECG, normal biomarkers, a low to intermediate pretest likelihood by risk stratification and no identifiable coronary cause for their chest pain.18 In the present study, we found that patients who met these guideline criteria had a 1-year event rate of 5%, as opposed to the approximately 1% 1-year event rate found in patients with NSCP for whom a clinical assessment does not suggest a need for additional diagnostic testing. While we did not perform CT angiography, we found that the presence of CAC in patients with NSCP did not differ from the background population. Thus, clinical assessments, with respect to risk-stratifying patients with NSCP for further testing, appear to be accurate. The differences in characteristics between those referred for further investigations and those included in our study without referral at index contact were not, however, explored in this study.

In our study, it was not possible to reach a conclusion on the prognostic value of CAC in predicting adverse cardiac events, largely due to the small number of study events, the short time to follow-up and the small number of participants. However, it is worth noting that both of the patients in the NSCP study population who had clinical events had very high CAC scores (349 and 2595), and both had three risk factors for CVD (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and a family history of CVD). This finding agrees with previous studies that have demonstrated that a high CAC score is a major and independent CVD risk factor.19 In concordance with previous studies, we found a very low event rate in patients without CAC.20 In the NSCP population, no cardiac events among patients with a CAC=0 were observed, while one person in the background population had VT and a CAC=0.

The NSCP population included more patients with hypercholesterolaemia compared with the background population (43% vs 18%). We know from previous studies that NSCP is associated with frequent contact with the healthcare system and higher medication use.21 This could partially explain why more patients in this group were diagnosed with hypercholesterolaemia.

Strengths/limitations

The outcome data collected from the Danish registries are well documented and validated, which adds strength to this study.22 23 The participants in this study and in the background population are likely healthier than the non-participants, with clinical trials involving the latter group demonstrating that they are at higher risk and have worse outcomes.24 The patients with NSCP and the background population were preselected to exclude individuals without risk factors as well as those with known CAD or coronary angiography within the last 5 years. Thereby, the results are not applicable to very-low-risk and high-risk patients, for whom risk stratification is a less relevant element of care. We know from previous validation studies that the self-reported data for CVD are under-reported and inaccurate compared with measured data.25 26 A sensitivity of 84.5% has been shown for hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes.25 This may have influenced the selection of our patients, since the presence of risk factors was an inclusion criteria. Patients who at index admission were referred for further investigations were not included in this study. They could have a higher prevalence of CAC that again would not be accounted for in this study.

The definition of risk factors varied between the study participants and the DanRisk comparator group. Family history was limited by age in the DanRisk study, whereas there was no age limit for patients with NSCP. This may explain the higher proportion of patients with a family history of CAD among patients with NSCP. Furthermore, the way that data was gathered differed: for patients with NSCP the values were extracted from an acute setting, while in contrast the DanRisk patients were investigated in a baseline examination (ie, the blood pressures were not obtained uniformly and thus not comparable).

The scanners and protocols that were used in the two studies differed, and this may have affected measurements of the presence of CAC. However, the centres and scanners used for the CAC assessment in the patients with NSCP and background population were almost the same and comparable for that reason.

Finally, the study was underpowered to show any differences in cardiac events. It is thus an observational study characterising the prevalence of CAC in patients with NSCP.

Conclusion

When adjusted for traditional CVD risk factors, the results of this study show that the presence of CAC in patients with NSCP does not significantly differ significantly from a background population. Specifically, a little more than half of patients with NSCP have detectable CAC on a cardiac CT scan. The prognosis for patients with NSCP appears to no worse than a background population with a combined cardiac event rate of <1%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the staff involved in the project at the Department of Cardiology and Nuclear Medicine, Odense University Hospital, the Department of Cardiology, Vejle Hospital, the Department of Cardiology and Radiology, Svendborg Hospital and the Department of Cardiology, Hospital of Southern Denmark.

Footnotes

Contributors: The steering committee (NI, HM, ATL, AD and CBM) designed the trial. NI and CBM obtained funding. The investigators (JL, FH, RA, JB, NPRS and MHG) trained the staff and gathered data. NI, AD, MHG and CBM analysed the data. NI, CBM, HM, ATL and AD wrote the report. All authors can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis, and all contributed to the implementation of the study, data interpretation and approval of the final report for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by the Region of Southern Denmark, Hospital of Southern Denmark, the University of Southern Denmark and Knud and Edith Eriksens memory foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Regional Scientific Ethical Committee for Southern Denmark (S-20140055).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 20122012;60:e44–e164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146–e603. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nowak R, Mueller C, Giannitsis E, et al. High sensitivity cardiac troponin T in patients not having an acute coronary syndrome: results from the TRAPID-AMI study. Biomarkers 2017;22:709–14. 10.1080/1354750X.2017.1334154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhuiya FA, Pitts SR, McCaig LF. Emergency department visits for chest pain and abdominal pain: United States, 1999-2008. NCHS Data Brief 2010;43:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fass R, Achem SR. Noncardiac chest pain: epidemiology, natural course and pathogenesis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;17:110–23. 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.2.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omstedt Å, Höijer J, Djärv T, et al. Hypertension predicts major adverse cardiac events after discharge from the emergency department with unspecified chest pain. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2016;5:441–8. 10.1177/2048872615626654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodacre S, Cross E, Arnold J, et al. The health care burden of acute chest pain. Heart 2005;91:229–30. 10.1136/hrt.2003.027599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khot UN, Khot MB, Bajzer CT, et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA 2003;290:898–904. 10.1001/jama.290.7.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;15:827–32. 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messenger B, Li D, Nasir K, et al. Coronary calcium scans and radiation exposure in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016;32:525–9. 10.1007/s10554-015-0799-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:620–33. 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budoff MJ, McClelland RL, Nasir K, et al. Cardiovascular events with absent or minimal coronary calcification: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am Heart J 2009;158:554–61. 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diederichsen AC, Sand NP, Nørgaard B, et al. Discrepancy between coronary artery calcium score and HeartScore in middle-aged Danes: the DanRisk study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2012;19:558–64. 10.1177/1741826711409172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budoff MJ, Diamond GA, Raggi P, et al. Continuous probabilistic prediction of angiographically significant coronary artery disease using electron beam tomography. Circulation 2002;105:1791–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000014483.43921.8C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laudon DA, Behrenbeck TR, Wood CM, et al. Computed tomographic coronary artery calcium assessment for evaluating chest pain in the emergency department: long-term outcome of a prospective blind study. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:314–22. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raff GL, Chinnaiyan KM, Cury RC, et al. SCCT guidelines on the use of coronary computed tomographic angiography for patients presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014;8:254–71. 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, et al. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA 2004;291:210–5. 10.1001/jama.291.2.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaikriangkrai K, Palamaner Subash Shantha G, Jhun HY, et al. Prognostic value of coronary artery calcium score in acute chest pain patients without known coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:659–70. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roll M, Rosenqvist M, Sjöborg B, et al. Unexplained acute chest pain in young adults: disease patterns and medication use 25 years later. Psychosom Med 2015;77:567–74. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bahit MC, Cannon CP, Antman EM, et al. Direct comparison of characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of patients enrolled versus patients not enrolled in a clinical trial at centers participating in the TIMI 9 Trial and TIMI 9 Registry. Am Heart J 2003;145:109–17. 10.1067/mhj.2003.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dey AK, Alyass A, Muir RT, et al. Validity of self-report of cardiovascular risk factors in a population at high risk for stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:2860–5. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowlin SJ, Morrill BD, Nafziger AN, et al. Reliability and changes in validity of self-reported cardiovascular disease risk factors using dual response: the behavioral risk factor survey. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:511–7. 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018391supp001.pdf (42.9KB, pdf)