Abstract

Objectives

Falls are an important adverse event among institutionalised persons. It is in this clinical setting where falls occur more frequently than in any other, despite the measures commonly taken to prevent them. This study aimed to determine the characteristics of a typical institutionalised elderly patient who suffers a fall and to describe the physical harms resulting from this event. We then examined the association between falls and the preventive measures used.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study in 37 nursing homes in Spain. The participants were all the nursing home residents institutionalised in these centres from May 2014 to July 2016. Participants were followed up for 9 months. During this period, two observations were made to evaluate the preventive measures taken and to record the occurrence of falls.

Results

896 residents were recruited, of whom 647 completed the study. During this period, 411 falls took place, affecting 213 residents. The injuries caused by the falls were mostly minor or moderate. They took place more frequently among women and provoked 22 fractures (5.35%). The most commonly used fall prevention measure was bed rails (53.53% of cases), followed by physical restraint (16.79%). The latter measure was associated with a higher incidence of injuries not requiring stitches (OR=2.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 4.22, P=0.054) and of injuries that did require stitches (OR=3.51, 95% CI 1.36 to 9.01, P=0.014) as a consequence of falls. Bed rails protected against night-time falls.

Conclusions

Falls are a very common adverse event in nursing homes. The prevention of falls is most commonly addressed by methods to restrain movement. The use of physical restraints is associated with a greater occurrence of injuries caused by a fall.

Keywords: accidental fall, physical restraint, accident prevention, nursing homes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study describes the type of people who fall in a large cohort in nursing home residents and the consequences of falls.

The most commonly used fall prevention measures are presented, and their relationship with incidence and fall injury is analysed.

The results of this study allow us to reflect on and question the suitability of fall prevention measures used in clinical practice in nursing homes.

The results are focused on the immediate physical harms resulting from falls. Wider consequences were not explored.

Background

Worldwide, falls are the second cause of death from accidental or unintentional injuries after road traffic injuries. Each year, falls provoke 424 000 deaths throughout the world, with the highest incidence in low-income and middle-income countries.1 According to the WHO, older people living in care institutions are more liable to fall than those living in the community; every year, 30%–50% of persons who are long-term resident in institutions suffer a fall, and 40% of them have more than one fall.2 Twenty to thirty per cent of elderly persons who fall suffer moderate to severe injuries, such as hip fractures or traumatic brain injury. These lesions reduce mobility and independence and increase the risk of premature death. In nursing homes and among women aged over 75 years, injury rates may be more than double the above figures.3 In addition to the physical and emotional costs provoked by falls, the economic consequences are significant, with direct costs estimated at about €19.2 billion dollars per year.4

The aetiology of falls has been the subject of various epidemiological studies. A systematic review found that for residents of nursing homes, the following factors were directly related: a history of falls (OR=3.06), using a walking aid (OR=2.08) and moderate disability (OR=2.08).5 Efforts to minimise falls in nursing homes, where advanced age and physical, mental and sensorial limitations are commonly present, often consist of multifactor interventions. To design effective preventive measures, it is necessary to determine the circumstances associated with falls, and the injuries they can provoke, to categorise which circumstances involve the most severe negative outcomes.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the characteristics (age, sex, level of consciousness) of institutionalised elderly persons who suffer falls, their circumstances (date, place, performed activity and presence or not of other people during the fall) and the physical harms resulting from this event. We also aimed to know what methods were adopted to prevent falls and then to analyse the association between falls and the preventive measures employed.

Methods

Study design

Prospective cohort study.

Participants

The study was carried out in institutions within the Nursing Homes Unit of the Malaga-Guadalhorce Health District, in Andalusia, southern Spain. This unit cares for 2541 persons resident in 68 nursing homes. The study participants were mostly elderly and institutionalised in these centres. The inclusion criteria applied were that they should be older than 16 years and resident in one of the above nursing homes throughout the study period or have entered during the study period. Those who refused to participate were excluded.

Sample

The necessary sample size was calculated according to the prevalence of falls reported in previous studies conducted in nursing homes. To detect a fall prevalence of 52%,6 with an alpha value of 0.05 in a population of 2541 institutionalised subjects and a precision of 4%, it was determined that 485 subjects should be recruited. This value was increased by 50% in anticipation of high mortality rates among the elderly population, and so the minimum sample required for the initial evaluation was 728 residents.

Data collection

The study was conducted from May 2014 to July 2016. The participants were recruited consecutively at each collaborating centre, and all of the residents at these 37 centres agreed to take part.

The data evaluated included the patients’ age and sex, the fall prevention measures employed (bed rails, physical restraints, the rearrangement of furniture and the suspension of psychotropic medication), the number of falls suffered, the level of consciousness when the fall occurred, the date and time of day, the circumstances (alone, walking and going to toilet) and the immediate harms resulting from each fall.

Bed rails were considered as side bars that prevent, limit or restrict the movements of a person, such as getting out of bed. Physical restraint was any device (wrist strap, abdominal belt or ankle brace) that attached or tied to the resident’s body limits the free movement of all or a part of the body.

In an initial assessment, the characterisation variables were collected, and the fall prevention measures were investigated. The same patients were reassessed 6 months later, after which they were followed for three more months to detect the occurrence of any additional falls in this period.

Falls were evaluated in three ways: by analysing the records maintained by each nursing home, verifying them with the caregiver staff and also with the patients themselves if their cognitive state allowed it. The definition adopted for a fall was that proposed by the WHO: ‘an event which results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground or floor or other lower level’.1 In all cases of falls, the nurses who collaborated with the project filled in a record form, stating the circumstances and consequences of each fall.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the variables were made by an exploratory analysis, which obtained measures of central tendency and dispersion or percentages, according to the nature of the variables. The normality of the distribution was evaluated in each case by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Asymmetry and/or kurtosis were also considered, and histograms of the distributions were obtained.

Bivariate analysis was performed using Student’s t-test and χ2 test, according to the characteristics of the variables, when they were normally distributed. Otherwise, non-parametric methods, such as the Wilcoxon, Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney U tests were used. The descriptors obtained were the joint and marginal distributions, with the mean, SD, measures of effect and 95% CIs. Correlational analyses between quantitative variables were performed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s r, depending on the nature of the parameter.

The statistical program used was SPSS V.22.

Ethical considerations

The clinical data were segregated from the identification data, and the databases were encrypted and stored in computers destined exclusively to this project. The data were collected online (Lime Survey), encrypted and hosted on a server with maximum security measures and password-coded access.

Results

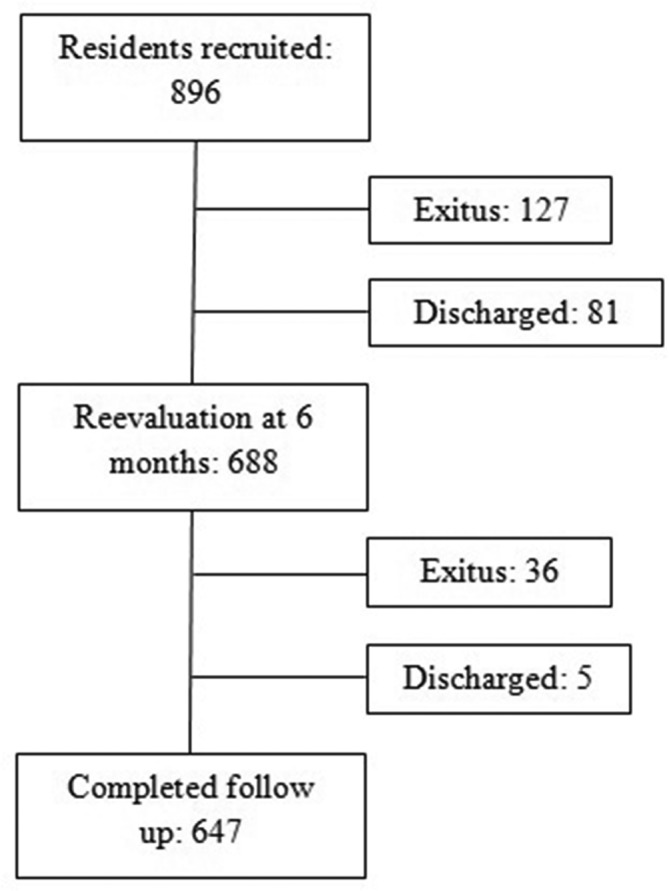

The study sample consisted of 896 nursing home residents. All received an initial assessment, and 688 (76.78%) were followed up and re-evaluated at 6 months. Finally, 647 patients completed the study after 9 months of follow-up (figure 1). Of the initial patients, 636 (71%) were women and 260 (29%) were men. The mean age was 81.81 years (SD 9.73) in a range between 36 and 102 years. The mean age of the women (83.89 years, SD 8.93) was significantly higher than that of the men (77.95 years, SD 10.51) (P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the study.

During the study period, 213 residents (23.77%, 95% CI 20.93% to 26.15%) suffered some fall, 88 of them had multiple falls. In total, there were 411 falls. The cumulative incidence of falls was 45.87%. Of those who fell, 155 (72.77%) were women, although there were no significant differences by sex between fallers and non-fallers (P=0.546) or between fallers and multiple fallers (P=0.518). The mean age of the fallers (83.45 years; SD 8.06) was significantly higher than that of the non-fallers (81.31 years; SD 10.14) (P=0.015). However, there were no significant differences by sex between those who suffered multiple falls (mean age 83.46 years, SD 8.34) and those who did not (mean age 83.51 years, SD 7.72) (P=0.907). The circumstances and immediate harms resulting from falls are shown in table 1. By days of the week, the largest number of falls took place on a Sunday (17.52%), and they were evenly distributed among the morning, afternoon and evening shifts. The patients who suffered falls were mainly conscious and well oriented (n=303, 73.72%). In 242 cases (58.88%), the patient was alone at the time of the fall, and on most occasions (n=305, 74.21%) the fall did not take place while the patient was walking. In 43 cases (10.46%), the fall occurred when the resident was going towards the toilet.

Table 1.

Characteristics and consequences of falls

| N (411) | % | |

| Day | ||

| Monday | 68 | 16.5 |

| Tuesday | 62 | 15.1 |

| Wednesday | 48 | 11.7 |

| Thursday | 54 | 13.1 |

| Friday | 64 | 15.6 |

| Saturday | 43 | 10.5 |

| Sunday | 72 | 17.5 |

| Shift | ||

| Morning | 146 | 35.5 |

| Afternoon | 142 | 34.5 |

| Night | 123 | 29.9 |

| Location* | ||

| Bed | 112 | 27.3 |

| Chair/armchair | 96 | 23.3 |

| Toilet/bathroom | 88 | 21.4 |

| Out of the room | 113 | 27.5 |

| Level of consciousness | ||

| Conscious and oriented | 303 | 73.7 |

| Disoriented | 93 | 22.6 |

| Nervous | 13 | 3.2 |

| Unconscious | 2 | 0.5 |

| Circumstances† | ||

| Alone | 242 | 58.9 |

| Walking | 106 | 25.8 |

| Going to the toilet | 43 | 10.5 |

| Preventive measures | ||

| None | 203 | 49.4 |

| Bed rails | 186 | 45.3 |

| Physical restraint | 50 | 12.2 |

| Suspension of psychotropic medication | 27 | 6.6 |

| Consequences | ||

| None | 243 | 59.1 |

| Haematoma | 87 | 21.2 |

| Internal haemorrhage | 1 | 0.2 |

| Nosebleed | 0 | 0 |

| Injury – no stitches needed | 60 | 14.6 |

| Injury – stitches needed | 23 | 5.6 |

| Dislocation/sprain | 3 | 0.7 |

| Fracture | 22 | 5.3 |

*Losses=2.

†Losses=20.

As shown in table 1, in 168 cases (40.88%) the fall provoked a physical harm to the resident, the most frequent being haematomas (n=87) and injuries not requiring stitches (n=60). There were 22 fractures (5.35%). The bivariate analysis revealed significant differences by sex concerning the day of the fall, with Sundays being more frequent among women (20.2%) and Mondays among men (22.8% of the falls affecting men occurred on this day of the week) (P=0.045). Women were more likely to fall in the morning (40.4%), while men more likely to fall at night (41.2%) (P=0.001). Men tended to fall from bed (40.4%), while women tended to fall from a chair (27.1%) (P=0.001). There were significantly more falls among men when they were alone (73.7%, P<0.001) and among women while they were walking (30%, P=0.002). Regarding the consequences, women were significantly more affected by falls than were men (44.4% vs 31.58%, respectively, P=0.019). By the type of consequence, fractures affected women more than men (n=20 vs n=2), but the difference was at the limit of statistical significance (P=0.05).

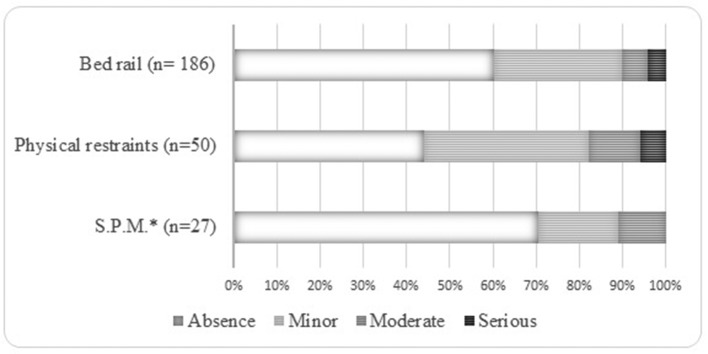

Concerning the preventive measures used, of the 1584 assessments made, bed rails were employed in 53.53% of cases; in 16.79%, there were physical restraints, and in 3.03%, the suspension of psychotropic medication. In no case was the clinical furniture rearranged. When falls took place, in 45.25% of the cases bed rails were fitted, in 12.16% there were physical restraints and in 6.57% the psychotropic medication had been suspended (table 1). The proportion of injuries due to falls (grouped in mild, moderate or serious injuries) according to the preventive measures adopted is shown in figure 2. An analysis was performed to determine whether any of the prevention measures adopted were related to injuries due to falls. In this respect, no significant relationship was observed between fall-related injuries and the use of bed rails or the suspension of psychotropic medication. However, the use of physical restraints was found to be significantly associated with such consequences, in 28 of the 50 falls with restraints (P=0.022). Specifically, the use of restraints was associated with a higher incidence of injuries not requiring stitches in 12 cases (OR=2.06, 95% CI 1.01 to 4.22), although the difference was at the limit of statistical significance (P=0.054). In seven cases, stitches were needed for injuries suffered when restraints were fitted (OR=3.51, 95% CI 1.36 to 9.01, P=0.014). None of the preventive measures examined were related to the occurrence of fractures following a fall. However, there was found to be a relation between the use of preventive measures and the following variables: the time of day, the place and the circumstances of the fall. When bed rails were used during the night, they had a protective effect, which is quite significant, as 37 of the 123 falls occurred during the night (P<0.001).

Figure 2.

Preventive measures and proportion of fall-related injuries. Fall-related injuries groups: absence (without injuries), minor (haematoma and injuries not requiring stitches), moderate (injuries requiring stitches and dislocation/sprain) and serious (internal haemorrhage and fracture). *S.P.M, suspension of psychotropic medication.

Discussion

Among the strengths of this study are the large sample size (n=896), the extended follow-up period (9 months) and its multicentre format, with the participation of 37 nursing homes for the elderly. The sample consisted mainly of women (71%) who, on average, were almost 6 years older than the male participants, which is in line with the greater longevity of the female sex. The majority of those who suffered falls were women too, but there were no differences by sex in the occurrence of one or more falls, a finding that corroborates previous research in this respect in nursing homes.7 The study subjects were elderly, with an average age of about 82 years. The results obtained confirm that advanced age is a risk factor for falls, with fallers being on average 2 years older than non-fallers.

The cumulative incidence of falls (45.87%) is within the range published in the literature in this context. In this respect, other authors have reported rates of 34%–46% in our country8 and even 52% in other country.6 In our study, over half of the falls that took place (59.12%) had no consequences on the patient, and when there were consequences, they usually took the form of minor injuries. Taking into account the minor injuries produced, whether stitches were required and the falls resulting in fractures, our results showed a slightly lower incidence of fractures with regards to those previously reported. Rubenstein9 concluded that in nursing homes, 10%–25% of falls result in fractures or injuries. Another study observed that ‘serious falls were associated with increasing age, being female, and less restricted functional status’.10 Our results show that women suffer more consequences from falls than men; nevertheless, there were no differences by sex as concerns injuries requiring stitches or not, or when the fall provoked a fracture. Although such consequences were more evident among women, the difference was at the limit of statistical significance.

Although several research studies have shown that exercise programmes are effective to prevent falls in long-term care facilities,11 the fall prevention strategies observed in our study are aimed at limiting mobility. The most commonly used fall prevention measure was that of bed rails, followed by physical restraints. In fall events, the presence of restraints was associated with a greater frequency of injuries, in particular those not requiring stitches (the difference was at the limit of significance) and those where stitches were required. Another preventive measure used was the suspension of psychotropic medication. A clinical practice guideline recommend: "older people on psychotropic medications should have their medication reviewed, with specialist input if appropriate, and discontinued if possible to reduce their risk of falling’.12 Nevertheless, this measure was adopted in only 3.03% of the assessments made. The use of methods of physical and pharmacological containment is a controversial topic, since it implies a restriction of mobility, which is detrimental to the patient’s functional capacity. A systematic review found no evidence that bed rails increased the risk of falls or of injuries from falls,13 in contrast to our own findings. Moreover, when bed rails were used during the night shift, fewer falls occurred. According to the Spanish Bioethics Committee,14 the use of restraints in nursing homes for the elderly is more common in Spain than elsewhere, reaching almost 40%, compared with 15% in countries such as France, Italy, Norway and the USA. The Spanish Bioethics Committee recommends that the use of mobility restrictions should be protocolised, supervised and subject to ongoing evaluation and, in all cases, should be performed with the consent of the patients or their guardians. The results obtained in the present study corroborate these recommendations, although the existence or otherwise of consent for the physical restraints used was not verified. That could be the subject of future studies. Cognitive impairment, severe mobility problems and a greatly restricted capacity to perform the activities of daily living are determinant factors in the decision to implement systems of restraint. With regard to fall prevention, the combination of these factors requires special nursing care. Paradoxically, the use of these containment systems has been associated with a higher incidence of falls,15 although in fact their use for nursing home residents is considered necessary by the staff who attends them. The prime reason for their use is, precisely, to prevent falls, as reported in a survey of nursing staff in Spain.16 The proper use of fall prevention measures could usefully be considered in a later study, together with consideration of the moral dilemma that would be posed to nursing staff if no measures of containment were applied to patients at risk. This moral dilemma should be taken into account in the realisation of future protocols, reinforcing the training of staff in this regard. It would be advisable to increase the periodicity of assessments to detect possible risk factors for recurrence and thus avoid possible falls.

This study has some limitations. In particular, the number of fall events may have been understated. To address this possibility, an event record table was created, distributed to all the nursing homes participating and collected weekly. On the collection day, the researchers directly considered the veracity of the data reported at the corresponding health centres. In addition, due to the nature of the study conducted, there could be contamination related to the implementation of fall prevention interventions in the nursing homes and a possible Hawthorne effect. Results are focused on immediate physical harm, but the wider consequences such as increasing dependency, fear of further falls, reduction in activity levels, hospital admissions, low mood or death have not been explored.

In conclusion, this study shows that falls are a common adverse event in nursing homes. They are related to advanced age and provoke injuries that are mainly slight to moderate. The method most commonly used to prevent falls is that of movement restriction. The use of physical restraints is associated with a greater occurrence of injuries due to falls.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the managers and collaborators of all nursing homes participating in the project.

Footnotes

Contributors: JMM-A and MA-G designed the study. MA-G, MEdL-R, MJV-B, JCC-S, JCM-H, FR-R and JCT-M were involved in data collection and evaluation. JMM-A performed the statistical analysis. All authors helped with the interpretation of the data. MA-G, MEdL-R, MJV-B and JMM-A drafted the first version of the manuscript, and all authors contributed to subsequent versions and revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Regional Health Ministry of Andalusia (PI-0152/2013); approval notification received December 2013.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Costa del Sol Research Ethics Committee (reference CS-0519).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available on request from the authors.

Collaborators: Ana Belen Moya-Suarez, Silvia Barrero-Sojo, Claudia Perez-Jimenez, Teresa Sanchez-Garcia, Raquel Ohara Arrebola-Lopez.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Ana Belen Moya-suarez, Silvia Barrero-sojo, Claudia Perez-jimenez, Teresa Sanchez-garcia, and Raquel Ohara Arrebola-lopez

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Falls. fact sheet No. 344. 2016. http://bit.ly/1i7Ixzq

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO global report on falls prevention in older age. 2007. http://bit.ly/1IltXUR

- 3.da Silva Gama ZA, Gómez Conesa A. Morbilidad, factores de riesgo y consecuencias de las caídas en ancianos. Fisioterapia 2008;30:142–51. 10.1016/S0211-5638(08)72972-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, et al. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Inj Prev 2006;12:290–5. 10.1136/ip.2005.011015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deandrea S, Bravi F, Turati F, et al. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;56:407–15. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer G, Köpke S, Haastert B, et al. Comparison of a fall risk assessment tool with nurses' judgement alone: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2009;38:417–23. 10.1093/ageing/afp049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharifi F, Fakhrzadeh H, Memari A, et al. Predicting risk of the fall among aged adult residents of a nursing home. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;61:124–30. 10.1016/j.archger.2015.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva Gama ZA, Gómez Conesa A, Sobral Ferreira M. Epidemiología de caídas de ancianos en España: Una revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2008;82:43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii37–41. 10.1093/ageing/afl084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Büchele G, Becker C, Cameron ID, et al. Predictors of serious consequences of falls in residential aged care: analysis of more than 70,000 falls from residents of Bavarian nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:559–63. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva RB, Eslick GD, Duque G. Exercise for falls and fracture prevention in long term care facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:685–9. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Falls: assessment and prevention of falls in older people | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. 2013. http://bit.ly/1PwhNcb [PubMed]

- 13.Healey F, Oliver D, Milne A, et al. The effect of bedrails on falls and injury: a systematic review of clinical studies. Age Ageing 2008;37:368–78. 10.1093/ageing/afn112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bioethics Committee of Spain. Consideraciones éticas y jurídicas sobre el uso de contenciones mecánicas y farmacológicas en los ámbitos social y sanitario. 2016. http://bit.ly/2yrzg5k

- 15.Hofmann H, Hahn S. Characteristics of nursing home residents and physical restraint: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:3012–24. 10.1111/jocn.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fariña-López E, Estévez-Guerra GJ, Gandoy-Crego M, et al. Perception of spanish nursing staff on the use of physical restraints. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:322–30. 10.1111/jnu.12087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.