Abstract

Objectives

There are limited data on mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Sub-Saharan Africa. We aimed at determining the mortality rate, and the causes and the predictors of death in patients with T2DM followed as outpatients in a reference hospital in Cameroon.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A reference hospital in Cameroon.

Participants

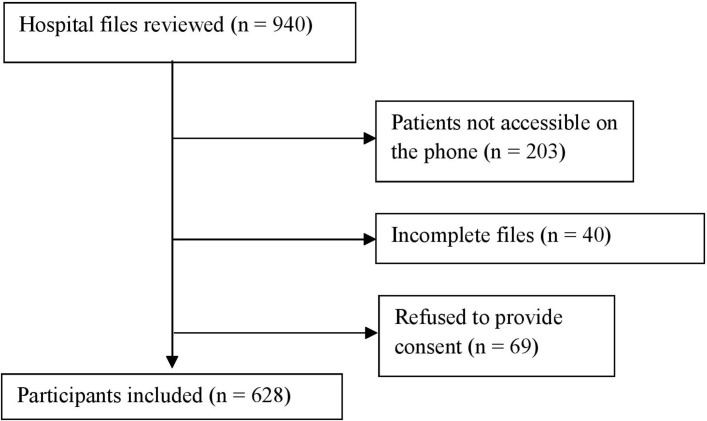

From December 2015 to March 2016, patients with T2DM aged 18 years and older and who consulted between January 2009 and December 2014, were contacted directly or through their next of kin, and included in this study. All participants with less than 75% of desired data in files, those who could not be reached on the phone and those who refused to provide consent were excluded from the study. Of the 940 eligible patients, 628 (352 men and 276 women) were included and completed the study, giving a response rate of 66.8%.

Outcome measures

Death rate, causes of death and predictors of death.

Results

Of the 628 patients (mean age: 56.5 years; median diabetes duration: 3.5 years) followed up for a total of 2161 person-years, 54 died, giving a mortality rate of 2.5 per 100 person-years and a cumulative mortality rate of 8.6%. Acute metabolic complications (22.2%), cardiovascular diseases (16.7%), cancers (14.8%), nephropathy (14.8%) and diabetic foot syndrome (13.0%) were the most common causes of death. Advanced age (adjusted HR (aHR) 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.10; P=0.002), raised glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (aHR 1.16, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.35; P=0.051), low blood haemoglobin (aHR 1.06, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.10; P=0.002) and proteinuria (aHR 2.97, 95% CI 1.40 to 6.28; P=0.004) were identified as independent predictors of death.

Conclusions

The mortality rate in patients with T2DM is high in our population, with acute metabolic complications as the leading cause. Patients with advanced age, raised HbA1c, anaemia or proteinuria are at higher risk of death and therefore represent the target of interest to prevent mortality in T2DM.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, mortality, survival, predictor, cause of death, Cameroon

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first over the past three decades to address long-term mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Our study provides the major causes and predictors of death in type 2 diabetes, which should be targeted for prevention.

Our study was conducted in a single and reference diabetes care centre; the results may not reflect the situation in primary care or in other reference centres in the country.

Introduction

Of the five million deaths attributable to diabetes in 2015, more than 321 100 occurred in the African region.1 Sadly, 79.0% of diabetes-related deaths in Africa occur in persons under the age of 60 years, in sharp contrast to 47.3% globally.1 Reducing the burden of diabetes requires promotional and preventive activities in the general population, timely diagnosis and effective management strategies in persons with diabetes, and identification of predictors and causes of death for effective control.2 While there have been extensive studies in developed countries on the causes and predictors of death in persons with diabetes,3–6 data remain very scant in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Coronary heart disease, complications related to neuropathy, nephropathy, infections, malignancies and acute metabolic complications are commonly reported as frequent causes of death in patients with diabetes.3 4 7 Using death registers, a study in Benghazi in Libya reported cardiovascular causes as the leading cause of death,7 while a 6-year follow-up study in Zimbabwe in the 1970s reported acute metabolic causes as the leading cause of death.8 Also, advanced age and poor glycaemic, cholesterol and blood pressure control are reported as being associated with increased mortality.9

To design meaningful interventions aimed at reducing the high diabetes-related mortality in the African region,10 we must identify the major context-specific causes and predictors of death. To the best of our knowledge, available studies on the causes of death and their determinants in SSA have been done on hospitalised patients,11 12 with mortality in outpatient cohorts less well investigated. However, a majority of patients with diabetes are managed as outpatients, and it is very important to identify the various factors associated with mortality in this group. To bridge this gap, we set out to determine the mortality rate, the causes of death and the predictors of death in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) being managed as outpatients at Douala General Hospital (DGH).

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

We carried out a retrospective cohort study at the outpatient diabetes and endocrine clinic of the DGH, a university teaching hospital located in Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon. The clinic is run by specialists in diabetes and endocrinology, who use the diabetes diagnostic criteria of the American Diabetes Association (ADA),2 and classify diabetes as type 1 or type 2 using the clinical criteria of probability. At first visits, all patients undergo comprehensive clinical and laboratory evaluation, then annually, which is aimed at screening for complications and comorbidities. Patients’ files are securely stored in the clinic’s archives and contain phone contacts for the patient and at least one kindred.

Inclusion criteria

The first step consisted of reviewing all patients’ files classified as having T2DM and whose first consultation was between January 2009 and December 2014. We retained hospital records that had at least 75% of required information and contained a valid phone number. Second, all patients whose files were retained were contacted directly or through their kindred by phone calls, from December 2015 to March 2016 (allowing for a minimum potential follow-up period of 12 months).

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients who could not be reached on the phone after a minimum of four calls over a period of 120 days and patients who did not consent to participate in the study.

Data collection and laboratory procedures

All collected data were filled in a structured data collection form. Clinical and laboratory data were retrieved from hospital records and included sociodemographic variables (age, gender, occupation and residence (urban or rural)), history of smoking (current smokers, past smokers and never smoked), physical exercise (sedentary, light, moderate and intense), weight, height, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, fasting capillary glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), parameters of the lipid profile, proteinuria and other complications.

First, we called the contact number on the patient’s hospital record to ascertain whether or not the patient was alive. In case a patient was dead, we expressed our condolences and sought for consent to participate in the study. The cause of death was determined by administering the WHO verbal autopsy instrument.13 For patients who died at DGH, the cause of death was further confirmed from hospitalisation records (13 cases) with more than 90% concordance rate.

Operational definitions for key variables were as follows:

type 2 diabetes mellitus: any patient diagnosed as such and confirmed by a specialist in accordance with the ADA guidelines2

hypertension: patients with a history of hypertension at inclusion, patients on antihypertensive drugs or patients whose systolic blood pressure was ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg, confirmed by the caring physician

dyslipidaemia: patients with history of dyslipidaemia whether on antilipidaemic drugs or not

causes of death: divided into the following categories, with their operational definitions:

acute metabolic diabetic complications: any acute coma prior to death

cardiovascular disease (CVD): any patient who died of diseases affecting the blood vessels and the heart

nephropathy: any confirmed acute or chronic kidney failure or any patient who was undergoing dialysis

infectious diseases: fever as major complaint, with or without confirmed infection prior to death

diabetic foot syndrome (DFS): any diabetic ulcer to gangrene of the foot or any amputations prior to death

cancers: any confirmed diagnosis of cancer prior to death.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) V.20. Categorical variables are presented as proportions and continuous variables as median (IQR) or mean (SD), as appropriate. The mortality rate is expressed in person-years and the cumulative mortality rate in percentage. Main statistical analyses used Cox proportional hazards model and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. To select variables for Cox regression, associations between independent variables and death were first investigated using binary logistic regressions for categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Variables with significant associations (potential confounders) with death in unadjusted analysis were retained for Cox regression. HbA1c, which did not meet this criterion, was purposefully retained and added into the model for consistency with prior studies. For illustrative purposes only, we generated cumulative Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the entire study population and stratified Kaplan-Meier curves for age (categorised as above and below the median), HbA1c (categorised as above and below the median), proteinuria (categorised as positive or negative) and haemoglobin (categorised as above and below the median), which remained statistically significant after multivariate Cox regression analyses. Participants with missing data for any specific analysis were treated as missing cases and dropped from the analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All participants or their carers gave verbal consent to participate in the study.

Results

General characteristics of participants

Of the 940 records reviewed during the study period, 628 (66.8%) were included in the study (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion of participants.

Men constituted 56.1% of the population. The mean age was 56.5±10.5 years, with majority of the participants aged between 50 and 59 years. The median duration of diabetes prior to inclusion was 43 (6–108) months and the median follow-up time was 37 (22.8–54.0) months. The median HbA1c at inclusion was 8.6% (6.8–10.6), and 25.8% of the participants had HbA1c values less than 7.0%. The general characteristics of the study participants are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants

| Variables | Categories | Total (n=628) | Male (n=352) | Female (n=276) | P* |

| Age (years) | 56.5 (10.5) | 57.0 (10.8) | 55.9 (10.2) | 0.13 | |

| DM duration at inclusion (years) | 3.6 (0.5–9) | 3.8 (0.5–3.7) | 3.5 (0.6–9.7) | 0.85 | |

| Length of follow-up (years) | 3.1 (1.9–4.5) | 3.0 (1.4–3.6) | 3.1 (2.0–4.0) | 0.21 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.5 (5.3) | 30.4 (5.8) | 28.7 (4.8) | <0.01 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 98 (90–106) | 97 (89–106) | 99 (92–106) | 0.06 | |

| Hip circumference (cm) (missing, n=71) | 105 (98–114) | 108.5 (100–118) | 103 (97–109) | <0.01 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 8.6 (6.8–10.6) | 9.0 (6.8–11) | 8.3 (6.8–10.4) | 0.69 | |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.1 (1.9) | 5.6 (1.7) | 6.5 (2.0) | <0.01 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139 (125–154) | 139 (127–155) | 139 (124–153) | 0.39 | |

| Creatinine level (mg/dL) | 0.96 (0.77–1.20) | 0.82 (0.69–1.06) | 1.06 (0.88–1.30) | <0.01 | |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 (11.3–13.3) | 13.3 (11.6–14.5) | 12.8 (11.4–13.9) | <0.01 | |

| Hypertension | 54.8 | 56.5 | 52.8 | 0.20 | |

| Dyslipidaemia | 25.2 | 28.4 | 21.2 | 0.04 | |

| Smoking | Currently smoking | 5.1 | 6.9 | 2.9 | <0.01 |

| Stopped smoking | 20.9 | 31.6 | 7.3 | ||

| Never smoked | 74.0 | 61.5 | 89.8 | ||

| Physical activity | Sedentary | 49.9 | 46.4 | 54.1 | 0.19 |

| Light physical activity | 26.5 | 26.8 | 26.2 | ||

| Moderate physical activity | 16.3 | 19.0 | 13.1 | ||

| Intense physical activity | 7.2 | 7.8 | 6.6 | ||

| Treatment | Lifestyle modification | 10.5 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 0.94 |

| OADs | 74.2 | 73.3 | 75.4 | ||

| OADs+insulin | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.9 | ||

| Insulin | 8.3 | 8.5 | 8.0 | ||

| Complications at diagnosis | None | 59.4 | 56.5 | 63.0 | 0.10 |

| Neuropathy | 18.8 | 20.7 | 16.3 | ||

| Nephropathy | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.2 | ||

| Retinopathy | 9.1 | 7.7 | 10.9 | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 6.4 | 8.3 | 4.0 | ||

| Leg ulcers | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

Data are presented as mean (SD) for normally distributed variables and median (25th–75th percentile) for variables not normally distributed.

*P for comparison between men and women.

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; OADs, oral antidiabetic drugs.

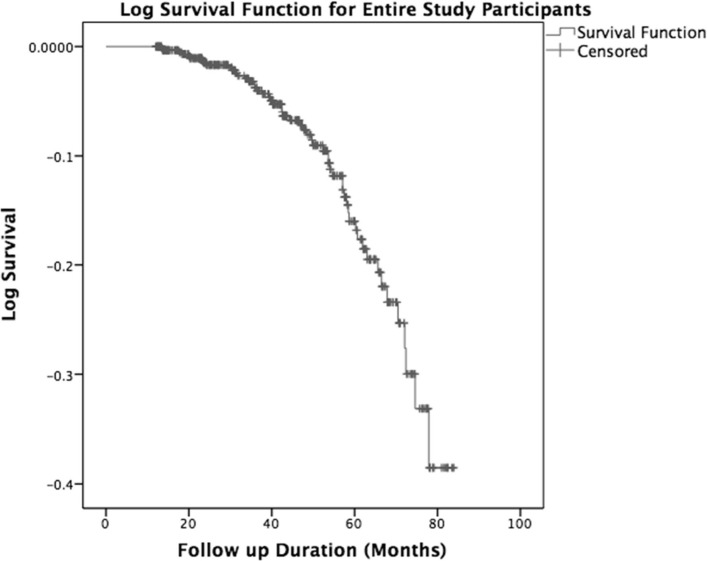

Mortality

Of the 628 patients followed up for a total of 2161 person-years, 54 died, giving a mortality rate of 2.5 per 100 person-years and a cumulative mortality rate of 8.6%. Men accounted for 55.6% of these deaths. On average, patients survived 6.3 years (95% CI 6.16 to 6.49), assuming they were all followed up for 7 years from recruitment (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival probability curves for the whole population.

Causes and predictors of death

Acute metabolic complications, CVDs, nephropathy, cancers and DFS accounted for the vast majority of deaths (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Causes of death obtained by verbal autopsy. AMC, acute metabolic complications; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DFS, diabetic foot syndrome.

Age, hypertension, HbA1c at inclusion, duration of diabetes prior to inclusion, proteinuria, antidiabetic drug category and haemoglobin were significantly associated with death in unadjusted models (table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate associations between various variables and death

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P |

| BMI | 0.95 | 0.90 to 1.02 | 0.11 |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus before inclusion | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.1 | <0.01 |

| HbA1c at inclusion | 1.08 | 0.96 to 1.20 | 0.21 |

| Waist circumference | 0.98 | 0.96 to 1.01 | 0.18 |

| Hip circumference | 0.98 | 0.5 to 1.00 | 0.60 |

| Age | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.09 | <0.01 |

| Uric acid | 1.06 | 0.87 to 1.28 | 0.58 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.00 | 0.9 to 1.01 | 0.29 |

| Haemoglobin | 0.84 | 0.74 to 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.26 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.02 | 0.58 to 1.79 | 0.939 |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.05 | 0.98 to 4.29 | 0.057 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 1 | ||

| Rural | 0.88 | 0.34 to 2.29 | 0.788 |

| Dyslipidaemia | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.41 | 0.77 to 2.58 | 0.268 |

| Proteinuria | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.70 | 1.33 to 5.46 | 0.006 |

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 1.00 | – | 0.50* |

| Stopped smoking | 0.34 | 0.05 to 2.55 | 0.29 |

| Currently Smoked | 1.17 | 0.00 to 1.66 | 0.65 |

| Complications at diagnosis | |||

| None | 1.00 | – | 0.22* |

| Retinopathy | 0.20 | 0.90 to 4.44 | 0.10 |

| Neuropathy | 0.57 | 0.23 to 1.40 | 0.22 |

| Nephropathy | 0.59 | 0.08 to 4.58 | 0.62 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 1.16 | 0.47 to 2.91 | 0.75 |

| Physical activity | |||

| Sedentary | 1.00 | – | 0.61* |

| Mild | 1.34 | 0.40 to 4.46 | 0.65 |

| Moderate | 1.00 | 0.30 to 3.78 | 1.00 |

| Intense | 0.72 | 0.16 to 3.19 | 0.70 |

| Antidiabetic drug categories | |||

| None | 1.00 | – | 0.01* |

| OAD | 0.90 | 0.34 to 2.40 | 0.83 |

| OAD and insulin | 3.14 | 0.97 to 10.10 | 0.06 |

| Insulin | 2.22 | 0.68 to 7.24 | 0.19 |

*P value across categories of the variable; significant p-values (<0.05) are indicated in bold; the reference category for each variable was arbitrarily attributed an OR of 1.

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; OAD, oral antidiabetic drugs.

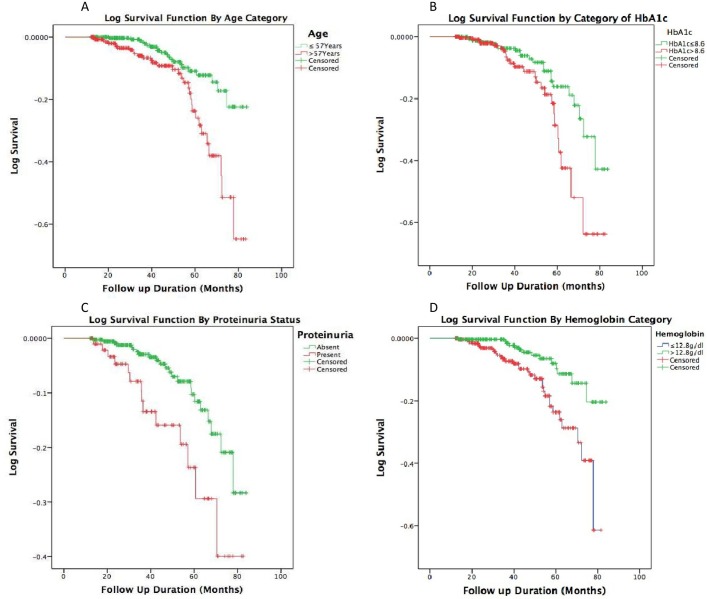

After adjustment in multivariate Cox regression analyses (table 3), age, HbA1c, blood haemoglobin level and proteinuria were independently associated with death. In fact, every increase of 1 year (age) and 1% HbA1c was associated with 6% and 16% higher mortality rates, respectively. Also, an increase of 1 g/dL of haemoglobin was associated with a 21% lower mortality rate. The presence of proteinuria was associated with 2.97 times the mortality rate among those with no proteinuria.

Table 3.

Adjusted HRs of predictors of death from Cox regression analysis

| Variable | Categories | Adjusted HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Age (years) | 1.06 | 1.02 to 1.10 | 0.002 | |

| HbA1c | 1.16 | 1.00 to 1.35 | 0.051 | |

| Haemoglobin | 0.79 | 0.65 to 0.96 | 0.016 | |

| Duration of diabetes | 0.99 | 0.93 to 1.05 | 0.782 | |

| Hypertension | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.34 | 0.51 to 3.50 | 0.554 | |

| Proteinuria | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.97 | 1.40 to 6.28 | 0.004 | |

| Diabetes drug | None | 1 | ||

| OAD | 1.83 | 0.23 to 14.42 | 0.565 | |

| OAD+insulin | 5.72 | 0.58 to 56.72 | 0.136 | |

| Insulin | 2.70 | 0.26 to 27.53 | 0.403 |

Significant p-values (<0.05) are indicated in bold. HbA1C, glycated haemoglobin; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug.

Graphical presentations for age, HbA1c, haemoglobin and proteinuria using stratified Kaplan-Meier survival plots are shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by median age (upper left), HbA1c (upper right), proteinuria (lower left) and median haemoglobin level (lower right) at inclusion. Green curves represent patients below the median age and HbA1c, with proteinuria, and above the median haemoglobin. Red curves represent patients above the median age and HbA1c, without proteinuria, and below the median haemoglobin. HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Discussion

Our study shows a mortality rate of 2.5 per 100 person-years and a cumulative mortality rate of 8.6% in outpatients with T2DM. We have identified acute metabolic complications, CVDs, nephropathy, cancers and DFS as the most frequent causes of death, and we also show that older age, higher HbA1c, lower blood haemoglobin levels and proteinuria are independently associated with death in this population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study over the past three decades to address mortality in patients with T2DM managed as outpatients in SSA.

Our cumulative mortality rate is higher than the 5.1% reported by Fabbian et al6 in Italy after 9.8 years of follow-up. Although not surprising, this might be explained by the fact that their patients had lower average HbA1c (7.4%) and Italy has a better health system with better access to quality care. Most studies on diabetes mortality in SSA were conducted on admitted patients,11 12 and their results cannot therefore be conveniently compared with ours because of huge differences in study populations. However, a study that observed 93 Africans diagnosed with diabetes in 1971 in Zimbabwe reported a 41% cumulative mortality after 6 years of follow-up.8 This high mortality rate is probably more reflective of the very poor life expectancy of patients with diabetes that prevailed in SSA in the 1970s and the global limitations in diabetes management at that time than an inherent higher mortality rate in Zimbabwe.

Acute metabolic complications were the most common cause of deaths in our study, consistent with findings from hospitalised patients in other African countries11 12 and the 6-year mortality reported in the 1970s in Zimbabwe.8 In middle-to-high income countries, however, CVDs accounted for most deaths.3 4 7 The consistency of acute metabolic complications as the most common cause of death in African population might be explained by similarities in patients’ characteristics and in limited access to quality care and medications. In low-income countries like Cameroon, most patients are less educated, poor and unable to pay for medications and refills compared with patients in more developed countries. These culminate in late diagnosis, poor adherence to medications and prescribed regimen, and in some cases total lack of medications, which are well-established risk factors for acute metabolic complications.14 Furthermore, studies done in more developed countries make use of death registries with a greater proportion of persons with longer duration of diabetes. This discrepancy in the causes of death might therefore suggest that over a short follow-up time, acute metabolic complications account for a greater proportion of deaths, while CVD is the major cause in persons with long-standing diabetes. However, CVD as the second most common cause of death in our study is a clear indication that CVD remains a major cause of death among persons with diabetes. Cancers were equally reported as a cause of death in our study, which is consistent with previous studies.15 Cancer-related deaths among patients with T2DM are not uncommon as there is an established association between cancer and diabetes.16–18 Consistent with previous reports,15 19 nephropathy was a major cause of deaths. Similarly, proteinuria, a proxy for kidney disease, was a major predictor of death in this study population. The non-negligible role of DFS as a cause of death in diabetes is further confirmed in our study.11 12

Age, proteinuria and HbA1c have been largely reported as independent predictors of death in other series.19–23 This reflects the increased death risk resulting from poor glycaemic control, nephropathy and comorbidities that occur with advanced age.24 25 Lower haemoglobin level as an independent predictor of death is of particular importance in our population where anaemia is prevalent, and was recently shown to be much more frequent in patients with T2DM.26 Although the exact pathway by which anaemia contributes to death among patients with diabetes is not well understood, we hypothesise that anaemia might serve as a proxy indicator of poor health status in this population.

We are cognizant of some limitations of our study, such as the modest sample size, which might not have allowed for robust associations to be accurately assessed; a single recruitment, which might not allow for generalisation to the entire Cameroon, where such standard of care is almost inexistent; and finally the use of verbal autopsy to ascertain the cause of death, which might not have allowed for precise cause of death to be established. However, the WHO verbal autopsy tool has been shown to be reliable in establishing the cause of death, which was further validated by confirming with hospital records (more than 90%). Despite these limitations, our study remains the most representative research piece on mortality in persons with T2DM in Cameroon specifically and SSA at large.

In conclusion, the mortality rate is high in patients with T2DM in our setting. Acute metabolic complications remain the major cause of death, followed by CVDs, nephropathy, cancers and DFS. Older age, higher levels of HbA1c, proteinuria and lower blood haemoglobin concentration are independent predictors of death. We strongly recommend that healthcare providers actively work on preventing and managing anaemia, controlling HbA1c and controlling proteinuria from any cause in patients with T2DM in order to reduce mortality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JBF: conception, data collection and writing of the manuscript. CD: data analysis, data interpretation and review of the manuscript. PNF: conception and review of the manuscript. YM-D: conception, data collection and manuscript review. DNN: study design, data collection and manuscript review. NDM: conception, data collection and manuscript review. VB: data collection, data interpretation and manuscript review. S-PC: conception and design, data collection, writing and review of the manuscript, and final approval.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Human Health of the University of Douala, Cameroon.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data collected for this study would be made available to all interested persons upon request. For all requests, kindly contact the corresponding author at schoukem@gmail.com.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 7th edn Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2015. http://www.diabetesatlas.org [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2017. Diabetes Care 2017;40(suppl 1). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romon I, Jougla E, Balkau B, et al. . The burden of diabetes-related mortality in France in 2002: an analysis using both underlying and multiple causes of death. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:327–34. 10.1007/s10654-008-9235-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura J, Kamiya H, Haneda M, et al. . Causes of death in Japanese patients with diabetes based on the results of a survey of 45,708 cases during 2001-2010: Report of the Committee on Causes of Death in Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2017;8:397–410. 10.1111/jdi.12645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen MB, Jensen ML, Carstensen B. Causes of death among diabetic patients in Denmark. Diabetologia 2012;55:294–302. 10.1007/s00125-011-2383-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabbian F, De Giorgi A, Monesi M, et al. . All-cause mortality and estimated renal function in type 2 diabetes mellitus outpatients: Is there a relationship with the equation used? Diab Vasc Dis Res 2015;12:46–52. 10.1177/1479164114552656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roaeid RB, Kablan AA. Diabetes mortality and causes of death in Benghazi: a 5-year retrospective analysis of death certificates. East Mediterr Health J 2010;16:65–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castle WM, Wicks AC. A follow-up of 93 newly diagnosed African diabetics for 6 years. Diabetologia 1980;18:121–3. 10.1007/BF00290487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang HH, Tseng FY, Wang CY, et al. . All-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes in association with achieved hemoglobin A(1c), systolic blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. PLoS One 2014;9:e109501 10.1371/journal.pone.0109501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jha P. Counting the dead is one of the world’s best investments to reduce premature mortality. Hypothesis 2012;10 10.5779/hypothesis.v10i1.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chijioke A, Adamu AN, Makusidi AM. Mortality patterns among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Endocrinol Metab Diabetes South Africa 2010;15:79–82. 10.1080/22201009.2010.10872231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unachukwu CN, Uchenna DI, Young E. Mortality among Diabetes In-Patients in Port-Harcourt, Nigeria. African J Endocrinol Metab 2010;7:1–4. 10.4314/ajem.v7i1.57567 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Verbal autopsy standards: ascertaining and attributing cause of death. 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland: WHO Press, World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer JA, Benedict A, Muszbek N, et al. . The significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a review. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:76–87. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01630.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tseng CH. Mortality and causes of death in a national sample of diabetic patients in Taiwan. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1605–9. 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, et al. . Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009;16:1103–23. 10.1677/ERC-09-0087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marble A. Diabetes and Cancer. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1934;211:339–49. 10.1056/NEJM193408232110801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. . Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1674–85. 10.2337/dc10-0666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barkoudah E, Skali H, Uno H, et al. . Mortality rates in trials of subjects with type 2 diabetes. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1:8–15. 10.1161/JAHA.111.000059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zargar AH, Wani AI, Masoodi SR, et al. . Causes of mortality in diabetes mellitus: data from a tertiary teaching hospital in India. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:227–32. 10.1136/pgmj.2008.067975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nwaneri C, Cooper H, Bowen-Jones D. Mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus: magnitude of the evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2013;13:192–207. 10.1177/1474651413495703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tancredi M, Rosengren A, Svensson AM, et al. . Excess Mortality among Persons with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1720–32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salles GF, Bloch KV, Cardoso CR. Mortality and predictors of mortality in a cohort of Brazilian type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1299–305. 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zoungas S, Chalmers J, Ninomiya T, et al. . Association of HbA1c levels with vascular complications and death in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of glycaemic thresholds. Diabetologia 2012;55:636–43. 10.1007/s00125-011-2404-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. . Retinal microvascular abnormalities and their relationship with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Surv Ophthalmol 2001;46:59–80. 10.1016/S0039-6257(01)00234-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feteh VF, Choukem SP, Kengne AP, et al. . Anemia in type 2 diabetic patients and correlation with kidney function in a tertiary care sub-Saharan African hospital: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:29 10.1186/s12882-016-0247-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.