Abstract

Objectives

This study aim to investigate the incidence, timing and risk factors of metachronous pulmonary recurrence after curative resection in patients with rectal cancer.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

This study was conducted at a tertiary referral cancer hospital.

Participants

A total of 404 patients with rectal cancer who underwent curative resection from 2007 to 2012 at Beijing Hospital were enrolled in this study.

Interventions

The pattern of recurrence was observed and evaluated.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The incidence and timing of recurrences by site were calculated, and the risk factors of pulmonary recurrence were analysed.

Results

The 5-year disease-free survival for the entire cohort was 77.0%. The most common site of recurrence was the lungs, with an incidence of 11.4%, followed by liver. Median interval from rectal surgery to diagnosis of pulmonary recurrence was much longer than that of hepatic recurrence (20 months vs 10 months, P=0.022). Tumour location, pathological tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage and positive circumferential resection margin were identified as independent risk factors for pulmonary recurrence. A predictive model based on the number of risk factors identified on multivariate analysis was developed, 5-year pulmonary recurrence-free survival for patients with 0, 1, 2 and 3 risk factors was 100%, 90.4%, 77.3% and 70.0%, respectively (P<0.001).

Conclusions

This study emphasised that the lung was the most common site of metachronous metastasis in patients with rectal cancer who underwent curative surgery. For patients with unfavourable risk profiles, a more intensive surveillance programme that could lead to the early detection of recurrence is strongly needed.

Keywords: pulmonary recurrence, rectal cancer, post-treatment surveillance

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study involved a large rectal cancer patient cohort; it had complete follow-up on all participants.

It was limited in that it was a retrospective analysis and only involved a single institution.

Some patient records such as the exact regimens and cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy may have been incomplete.

Only a third of the metastases were confirmed histologically or cytologically; the proportion was lower than in other studies.

Introduction

Although multimodal therapy including preoperative chemoradiotherapy and total mesorectal excision has effectively lowered the local failure rate in patients with rectal cancer,1 it has not significantly improved survival because the high rate of distant metastasis remained unsolved.2 3 Previous reports have indicated that 20%–50% of patients with rectal cancer will eventually develop metachronous metastases.2 3 The liver is the predominant site of distant metastasis in patients with colorectal cancer.4 5 Several recent reports have shown that pulmonary recurrence was detected more frequently than hepatic recurrence in patients with rectal cancer.6–15 However, this concept has not been fully recognised; many clinicians still believed that rectal cancer most frequently recurs in the liver.

We investigated the incidence, timing and prognosis of metachronous pulmonary metastasis following curative resection in a large cohort of patients with rectal cancer after long-term follow-up. Predictive factors for pulmonary recurrence were also identified. In addition, suggestions for individuated surveillance strategies that could increase early detection of recurrence are provided.

Materials and methods

Patients

Data from consecutive patients with rectal cancer who underwent curative resection with total mesorectal excision at the Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Beijing Hospital, Beijing, China, were recorded and stored in a database. We retrospectively analysed records from patients treated during the period from January 2007 to March 2012 who met the following criteria: (1) tumours with inferior border ≤15 cm from the anal verge, based on intraoperative findings in addition to preoperative digital rectal examination and colonoscopy; (2) preoperative pathological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma; (3) no distant metastasis or multiple primary malignant neoplasms; and (4) no history of other malignant disease.

Preoperative MRI assessment

All patients from this study underwent a high-resolution MRI according to standard protocol.16 17 magnetic resonance T (mrT) stage was defined as: mrT1: submucosa invasion; mrT2: muscularis propria invasion; mrT3: tumour invades subserosa through muscularis propria; and mrT4: tumour invades other organs.16 magnetic resonance N (mrN) status was assessed based on size of the nodes and the outline of the node and features of signal intensity (mrN1: 1–3 nodes, mrN2: ≥4 nodes).16 A MRI tumour height was determined by distance between the inferior border of tumour to the anal verge on sagittal view. The relationship of the tumour to the mesorectal fascia was reported, and circumferential resection margin (CRM) involvement was defined as tumour ≤1 mm from mesorectal fascia.

Treatment

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was recommended for locally advanced disease (mrT3–4 or mrN+), and the final decision was made through discussion between the patient and surgeon(s). For these patients, a total dose of 50.4 Gy was delivered in 28 fractions of 1.8 Gy each within a period of 6 weeks. Capecitabine was administered concurrently with radiotherapy at a dose of 825 mg/m2 orally twice per day. Surgery was planned to take place at 5–12 weeks after the last radiation dose was delivered. All patients underwent radical resection of the rectal cancer according to the principles of total mesorectal excision.18 The eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system was used for pathological staging. Postoperative 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy (capecitabine alone, mfolfoX6, or Capeox) was routinely recommended to the patients, regardless of the surgical pathology results.

Follow-up

Patients were routinely followed every 3 months after surgery for the first 2 years, every 6 months for another 3 years and annually thereafter. The evaluation included a clinical examination, measurement of the levels of tumour markers including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9 and CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Colonoscopy was performed every 6 months. Time to recurrence was defined as the time interval from surgical resection of the primary tumour to the date of diagnosis of the first recurrence. The diagnosis of recurrence was confirmed by pathological analysis through biopsy, obviously abnormal imaging findings or a combination of an elevated CEA level, serial CT and/or positron emission tomography scans.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sites of recurrence as well as the time to diagnosis of recurrence. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for time-dependent analyses, and log-rank tests were used to compare the proportions of patients with recurrence with the clinical and pathological characteristics. All variables that were significant on univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate analysis that was performed by using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. HRs and associated 95% CIs were reported. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS V.19.0 software. All significance tests were two tailed, and a P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patients characteristics and clinicopathological features

A total of 570 patients underwent resection in our institution, 166 patients were excluded and 404 patients were finally enrolled in the study. The median age was 68 years (range 34–94), and 235 (58.2%) patients were male. The median follow-up period for all of the patients was 61 months (range 21–142). An elevated CEA level (≥5 ng/mL) was detected in 151 (37.4%) patients. The median distal tumour margin from the anal verge was 8 cm (range 0–15). The tumour was located in the lower rectum (<5 cm) in 140 (34.7%) of the patients. At the time of initial diagnosis, clinical stage I, II and III were found in 9 (2.2%), 69 (17.1%) and 326 (80.7%) patients. As for the pathological staging, 66.4% of the patients had advanced T stage (pT3/4) and 42.3% had positive nodal involvement (pN1/2). CRM involvement was observed in 23 (5.7%) of the patients. A sphincter-preserving surgery was performed in 278 (68.8%) of patients. A total of 133 patients (32.9%) received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, and 140 patients (34.7%) received adjuvant chemotherapy at our institution. The characteristics and clinicopathological features of all 404 patients are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and clinicopathological features

| Characteristics | Value |

| Median age (range) | 68 (34–94) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 169 (41.8) |

| Male | 235 (58.2) |

| Preoperative CEA level, n (%) | |

| <5 ng/mL | 243 (62.6) |

| ≥5 ng/mL | 151 (37.4) |

| Distance of tumour from anal verge, n (%) | |

| <5 cm | 140 (34.7) |

| ≥5 cm | 264 (65.3) |

| Pretreatment clinical stage, n (%) | |

| I | 9 (2.2) |

| II | 69 (17.1) |

| III | 326 (80.7) |

| Circumferential margin, n (%) | |

| ≤1 mm | 23 (5.7) |

| >1 mm | 381 (94.3) |

| Lymphovascular invasion, n (%) | |

| Positive | 44 (10.9) |

| Negative | 360 (89.1) |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | |

| LAR | 273 (67.6) |

| APR | 126 (31.2) |

| Hartmann | 5 (1.2) |

| Differentiation of adenocarcinoma, n (%) | |

| Not determined pCR | 24 (5.9) |

| Well | 8 (2.0) |

| Moderate | 274 (67.8) |

| Poor | 52 (12.9) |

| Undifferentiated | 46 (11.4) |

| Pathological T stage, n (%) | |

| pT0/ypT0 | 0 (0)/24 (18.0) |

| pT1/ypT1 | 0 (0)/12 (9.0) |

| pT2/ypT2 | 43 (15.9)/57 (42.9) |

| pT3/ypT3 | 211 (77.9)/37 (27.8) |

| pT4/ypT4 | 17 (6.3)/3 (2.3) |

| Pathological N stage, n (%) | |

| pN0/ypN0 | 130 (48.0)/103 (77.4) |

| pN1/ypN1 | 77 (28.4)/22 (16.5) |

| pN2/ypN2 | 64 (23.6)/8 (6.0) |

| Pathological TNM stage, n (%) | |

| yp0 | 21 (15.8) |

| pI/ypI | 23 (8.5)/21 (15.8) |

| pII/ypII | 105 (37.7)/65 (48.9) |

| pIII/ypIII | 143 (52.8)/28 (21.1) |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 133 (32.9) |

| No | 271 (67.1) |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n (%) | |

| Yes | 140 (34.7) |

| No | 264 (65.3) |

APR, abdominoperineal resection; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; LAR, l ow anterior resection; pCR, pathological complete response; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; yp, pathological stage after neoadjuvant therapy.

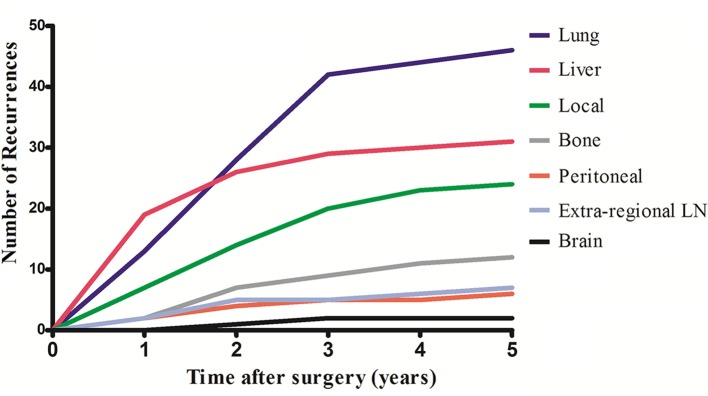

The incidence of distant metastases and local recurrence

At the time of the final analysis, 93 patients (23.0%) developed recurrent disease, and the diagnosis for 32 of these patients (34.4%) was confirmed histologically or cytologically. The 5-year disease-free survival for the entire cohort was 77.0%. Twenty-five patients (6.2%) developed local recurrence, 81 (20.0%) developed distant metastases and 13 (3.2%) developed both local recurrence and distant metastases. Of the 93 patients who developed recurrence, single-organ recurrence occurred in 62 patients (66.7%), and multiple recurrence was discovered in 21 patients (33.3%). The most common site of metastases was the lung (n=46), with an incidence of 11.4%, followed by liver (n=31, 7.7%), bone (n=13, 3.2%), extraregional lymph nodes (n=7, 1.7%), peritoneum (n=6, 1.5%) and brain (n=2, 0.5%). The development of recurrences by site over time is shown in figure 1. Among the 22 patients with multiple organs metastases, the liver and lung were the most common combination, which affected 10 (45.5%) of the patients. Six patients with recurrence had three or more organs involved. Among the 59 patients with single-organ metastases, lung was a site of relapse in 49.2% (n=29), followed by liver (n=17, 28.8%), bone (n=6, 10.2%), peritoneum (n=3, 5.1%), brain (n=2, 3.4%) and extraregional lymph nodes (n=2, 3.4%). For patients who developed recurrent disease, surgery was performed for 24 patients (25.8%), chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy were performed for 41 patients (44.1%) and 23 patients (24.7%) received best supportive care.

Figure 1.

Number of recurrences by site over time. LN, lymph node.

Risk factors for pulmonary and overall recurrence

Univariate analysis regarding the clinicopathological features as prognostic factors for pulmonary and overall recurrence was performed, and the results are presented in table 2. According to this analysis, pulmonary recurrence was significantly associated with tumour location (P=0.003), elevated preoperative CEA level (P=0.026), positive CRM (P<0.001) and advanced pathological TNM stage (P<0.001). Other factors including sex, clinical stage, lymphovascular invasion, surgical procedure, neoadjuvant/adjuvant treatment and tumour differentiation were not associated with pulmonary recurrence.

Table 2.

Univariate analyses regarding the risk factors of pulmonary and overall recurrence

| Characteristics | Patients (n) | 5-year PRFS (%) | P value | 5-year DFS | P value |

| Distal tumour margin from anal verge | 0.003 | 0.069 | |||

| <5 cm | 140 | 82.9 | 79.2 | ||

| ≥5 cm | 264 | 91.7 | 72.9 | ||

| Pretreatment clinical stage | 0.072 | 0.016 | |||

| I/II | 78 | 94.9 | 88.5 | ||

| III | 326 | 87.1 | 74.2 | ||

| Preoperative CEA level | 0.026 | 0.147 | |||

| <5 ng/mL | 253 | 90.9 | 79.1 | ||

| ≥5 ng/mL | 151 | 84.8 | 73.5 | ||

| Circumferential margin | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| ≤1 mm | 23 | 65.2 | 34.8 | ||

| >1 mm | 381 | 90 | 79.5 | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.235 | 0.044 | |||

| Positive | 44 | 84.1 | 65.9 | ||

| Negative | 360 | 89.2 | 78.3 | ||

| Surgical procedure | 0.425 | 0.624 | |||

| LAR/Hartmann | 278 | 87.4 | 77.0 | ||

| APR | 126 | 91.3 | 77.0 | ||

| Differentiation of adenocarcinoma | 0.129 | 0.002 | |||

| pCR, well, moderate | 306 | 89.9 | 80.4 | ||

| Poor and undifferentiated | 98 | 84.7 | 66.3 | ||

| p/ypTNM stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 0–I | 109 | 98.2 | 93.6 | ||

| II–III | 295 | 85.1 | 70.8 |

APR, abdominoperineal resection; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; DFS, disease-free survival; LAR, low anterior resection; pCR, pathological complete response; PRFS, pulmonary recurrence-free survival; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; yp, pathological stage after neoadjuvant therapy.

Factors associated with overall recurrence included pretreatment clinical stage (P=0.016), positive CRM (P<0.001), lymphovascular invasion (P=0.044), tumour differentiation (P=0.002) and advanced pathological TNM stage (P<0.001).

On multivariate analysis, pulmonary recurrence was significantly associated with pathological TNM stage (II/III vs 0/I, HR=8.823, 95% CI 2.134 to 36.475; P=0.003), CRM(≤1 vs >1 mm, HR=3.127, 95% CI 1.503 to 6.506; P=0.002) and tumour location (<5 vs ≥5 cm, HR=1.955, 95% CI 1.104 to 3.463; P=0.022). Among all the variables related to the development of overall recurrence on univariate analysis, pathological TNM stage (HR=5.084, 95% CI 2.348 to 11.009; P<0.001) and CRM (HR=2.032, 95% CI 1.081 to 3.820; P=0.028) was significant on logistic regression multivariate analysis. The independent risk factors associated with pulmonary and overall recurrence on multivariate analyses are shown in table 3.

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses regarding the risk factors of pulmonary and overall recurrence

| Characteristics | Pulmonary recurrence | Overall recurrence | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| p/ypTNM stage (II/III vs 0/I) | 8.823 (2.134 to 36.475) | 0.003 | 5.084 (2.348 to 11.009) | <0.001 |

| Circumferential margin (≤1 vs >1 mm) | 3.127 (1.503 to 6.506) | 0.002 | 2.032 (1.081 to 3.820) | 0.028 |

| Tumour location (<5 vs ≥5 cm) | 1.955 (1.104 to 3.463) | 0.022 | 1.376 (0.906 to 2.090) | 0.134 |

TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; yp, pathological stage after neoadjuvant therapy.

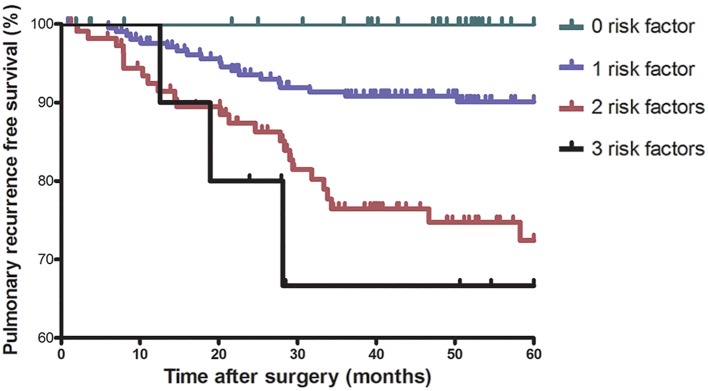

The risk of pulmonary recurrence in patients with different numbers of risk factors identified on multivariate analysis were evaluated. The number of patients with 0, 1, 2 and 3 risk factors were 76 (18.8%), 208 (51.5%), 110 (27.2%) and 10 (2.5%). Five-year pulmonary recurrence-free survival (PRFS) for patients with 0, 1, 2 and 3 risk factors was 100%, 90.4%, 77.3% and 70.0%, respectively (P<0.001) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Five-year pulmonary recurrence-free survival stratified according to the number of risk factors.

Incidence of hepatic and pulmonary recurrences in different locations

For patients with tumour located <5 cm from anal verge, the incidence of pulmonary and hepatic recurrence were 17.1% (24/140) and 5.7% (8/140), respectively, and the ratio of hepatic-to-pulmonary recurrences was 0.33. However, the incidence of pulmonary and hepatic recurrence were 8.3% (22/264) and 8.7% (23/264) for tumour ≥5 cm, and the ratio of hepatic-to-pulmonary recurrences increased to 1.04.

Timing of pulmonary and hepatic recurrence

In the study, 86.0% of recurrence occurred within 3 years after primary surgical resection and 96.8% within 5 years. The median time interval from the surgical resection to the development of recurrence was 18 months. The median interval from the surgical resection to the diagnosis of pulmonary metastases was much longer than that of hepatic metastases (20 vs 10 months, P=0.022). Of the patients with pulmonary recurrence, relapse was detected in 13 patients (28.3%) in the first year, 15 (32.6%) in the second year and 14 (30.4%) in the third year. Only four patients (8.7%) were diagnosed with recurrence after 3 years.

In contrast to pulmonary recurrence, the majority of patients with hepatic recurrence (n=19, 59.4%) were diagnosed within the first year. After the first year, hepatic recurrence was only detected in 13 patients (40.6%) after the first year. The timing of development of pulmonary and hepatic recurrence are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Timing of development of pulmonary and hepatic recurrence.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported that 20%–50% of patients with rectal cancer developed metastatic disease, frequently in the liver, lung, peritoneum, bone and extraregional lymph nodes.2 3 It has been generally recognised that the main metastasis site of colorectal cancer was the liver, followed by the lung.3–5 However, several recently published studies have found that the lung was the main site of metastasis of rectal cancer after curative resection, with an incidence of up to 12%.7–14 However, most clinician continued to believe that the liver is the most frequent site of distant relapse.

The present study investigated the incidence and timing of metachronous pulmonary metastasis after curative resection in a large cohort of patients with rectal cancer after long-term follow-up. Predictive factors for metastasis were also identified. In our study, one in five patients developed metastatic disease; lung was the most common site for metastasis, with an incidence of 11.4%, which was approximately 1.5 times that of liver metastasis. These results were consistent with the findings of previous studies.10–14 In addition, we observed that the timing of pulmonary recurrence was significantly different from those of the hepatic recurrence.

Various theories have been proposed to explain why pulmonary metastases have been detected more frequently in patients with rectal cancer than those with colon cancer.7 19 20 The most plausible explanation is based on anatomical features of the venous drainage system of the rectum. While colon cancer and upper rectal cancer cells travel via the portal blood flow into the liver, lower rectal cancer cells may directly spread into the systemic circulation and lungs via the inferior and middle rectal veins that drain into the inferior vena cava, bypassing the portal venous system.10 11

Watanabe and colleagues revealed that patients with cancer at the lowest region of the rectum had a higher risk of developing pulmonary metastases compared with patients with upper and lower rectal cancer.10 Recent studies also suggested that the rate of pulmonary recurrence was significantly higher in the lower group than in the middle and upper groups of patients with rectal cancer.6 12 In the present study, we also found that the rate of pulmonary recurrence in patients with lower rectal cancer (<5 cm) was twice higher than that of patients in upper group. However, no significant difference in the rate of overall recurrence was also observed between patients with tumours located less than or greater than 5 cm. We suppose that the location of tumour was a primary cause for the high incidence of pulmonary metastases in patients with rectal cancer.

This study also highlight the timing of metastases. Nearly 90% of both pulmonary and hepatic metastases were diagnosed within 3 years after curative surgery, which is in agreement with previous findings.2–4 21 22 However, the results of our study indicated that the timing was quite different between patients with pulmonary and hepatic metastases. Pulmonary metastases were detected evenly in the first 3 years after curative surgery (28.3%, 32.6% and 30.4%). Lee et al found that the rate of pulmonary recurrence continued to increase between the first and the third year postsurgery.12 Whereas the liver was the predominant site of recurrence during the early period after surgery, nearly 60% of hepatic metastases occurred in the first year; however, there was a rapid decrease in the following years.

High-resolution chest CT scans have been shown to be capable of detecting small lung metastatic lesions.23 In our institution, post-treatment surveillance was performed with chest CT rather than X-ray; however, CT has not been routinely used for surveillance in all patients in China. In early metastatic cases, lung nodules are quite small, and it is therefore difficult to distinguish pulmonary metastases from other benign lesions. Even when CT scans are performed, it is possible to underestimate the incidence of pulmonary metastases.24 Moreover, some patients prefer to receive continual follow-up rather than needle biopsy or thoracoscopic exploration. The diagnosis of pulmonary metastases was confirmed after obvious changes in the number or size of lung nodules were observed. Therefore, the interval from detection to confirmation of pulmonary metastases was largely extended.25 26

Previous studies have investigated several clinical and pathological factors that may be related to metachronous metastasis after curative treatment of rectal cancer.10 11 24 27 28 Apart from the tumour location as mentioned above, factors such as pathological TNM stage and positive CRM were found to be independent risk factors for pulmonary recurrence. According to the three identified risk factors, we have developed a predictive model to further stratify patients at different risk of pulmonary recurrence. Five-year PRFS for low-risk patients (0 and 1 risk factors) was 100% and 90.4%. While patients with 2 and 3 factors were at high risk of pulmonary recurrence, 5-year PRFS was only 77.3% and 70.0%, respectively.

The findings presented here may influence the individualised post-treatment surveillance. Based on the different patterns and different risk profiles of pulmonary recurrence, more tailored surveillance programmes should be developed. Since our results suggest a preponderance of pulmonary recurrence, more attention should be paid to detecting potential recurrence in lung. For patients with two or more risk factors, more intensive surveillance for pulmonary metastases by chest CT throughout the first 3 years is strongly recommended. A shorter interval (eg, every 3–6 months) of imaging is of great importance for early detection of potential pulmonary metastases. However, those with favourable risk profiles (0 or one risk factors) may be surveilled with less intensive protocol. In addition, hepatic metastases are mainly diagnosed within the first year after surgical resection; more intensive methods such as MRI or contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the liver should be considered during the early postoperative period.

This study emphasised that the lung was the most common site of metachronous metastasis in patients with rectal cancer who underwent curative surgery. Tumour location, pathological TNM stage and positive CRM were identified as independent risk factors for pulmonary recurrence. For patients with unfavourable risk profiles, a more intensive surveillance programme that could lead to the early detection of recurrence is strongly needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: H-DP and GX designed the study; H-DP, GZ and QA acquired the data and drafted the article; H-DP and GZ analysed and interpreted the data; GX revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the version to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.van Gijn W, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer: 12-year follow-up of the multicentre, randomised controlled TME trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:575–82. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tjandra JJ, Chan MK. Follow-up after curative resection of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:1783–99. 10.1007/s10350-007-9030-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manfredi S, Bouvier AM, Lepage C, et al. Incidence and patterns of recurrence after resection for cure of colonic cancer in a well defined population. Br J Surg 2006;93:1115–22. 10.1002/bjs.5349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo SI, Lim SB, Yoon YS, et al. Comparison of recurrence patterns between ≤5 years and >5 years after curative operations in colorectal cancer patients. J Surg Oncol 2013;108:9–13. 10.1002/jso.23349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chau I, Allen MJ, Cunningham D, et al. The value of routine serum carcino-embryonic antigen measurement and computed tomography in the surveillance of patients after adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1420–9. 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikoma N, You YN, Bednarski BK, et al. Impact of recurrence and salvage surgery on survival after multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2631–8. 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitry E, Guiu B, Cosconea S, et al. Epidemiology, management and prognosis of colorectal cancer with lung metastases: a 30-year population-based study. Gut 2010;59:1383–8. 10.1136/gut.2010.211557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan KK, Lopes GL, Sim R. How uncommon are isolated lung metastases in colorectal cancer? A review from database of 754 patients over 4 years. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:642–8. 10.1007/s11605-008-0757-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Gestel YR, de Hingh IH, van Herk-Sukel MP, et al. Patterns of metachronous metastases after curative treatment of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 2014;38:448–54. 10.1016/j.canep.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe K, Saito N, Sugito M, et al. Predictive factors for pulmonary metastases after curative resection of rectal cancer without preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 2011;54:989–98. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31821b9bf2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang JM, Hsieh PS, Chen JS, et al. Rectal cancer level significantly affects rates and patterns of distant metastases among rectal cancer patients post curative-intent surgery without neoadjuvant therapy. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:197 10.1186/1477-7819-12-197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JL, Yu CS, Kim TW, et al. Rate of pulmonary metastasis varies with location of rectal cancer in the patients undergoing curative resection. World J Surg 2015;39:759–68. 10.1007/s00268-014-2870-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding P, Liska D, Tang P, et al. Pulmonary recurrence predominates after combined modality therapy for rectal cancer: an original retrospective study. Ann Surg 2012;256:111–6. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825b3a2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arredondo J, Baixauli J, Beorlegui C, et al. Prognosis factors for recurrence in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer preoperatively treated with chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum 2013;56:416–21. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318274d9c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson JR, Newcomb PA, Hardikar S, et al. Stage IV colorectal cancer primary site and patterns of distant metastasis. Cancer Epidemiol 2017;48:92–5. 10.1016/j.canep.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor FG, Swift RI, Blomqvist L, et al. A systematic approach to the interpretation of preoperative staging MRI for rectal cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;191:1827–35. 10.2214/AJR.08.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MERCURY Study Group. Extramural depth of tumor invasion at thin-section MR in patients with rectal cancer: results of the MERCURY study. Radiology 2007;243:132–9. 10.1148/radiol.2431051825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Ryall RD, et al. Rectal cancer: the Basingstoke experience of total mesorectal excision, 1978-1997. Arch Surg 1998;133:894–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada H, Ichikawa W, Uetake H, et al. Thymidylate synthase gene expression in primary colorectal cancer and metastatic sites. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2001;1:169–73. 10.3816/CCC.2001.n.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Assersohn L, Norman A, Cunningham D, et al. Influence of metastatic site as an additional predictor for response and outcome in advanced colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 1999;79:1800–5. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6990287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho YB, Chun HK, Yun HR, et al. Clinical and pathologic evaluation of patients with recurrence of colorectal cancer five or more years after curative resection. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:1204–10. 10.1007/s10350-007-0247-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Ishikawa K, et al. Recurrence patterns after curative resection of colorectal cancer in patients followed for a minimum of ten years. Hepatogastroenterology 2003;50:1362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al. Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:4465–70. 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.7442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirke R, Rajesh A, Verma R, et al. Rectal cancer: incidence of pulmonary metastases on thoracic CT and correlation with T staging. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2007;31:569–71. 10.1097/rct.0b013e318032e8c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2005;237:395–400. 10.1148/radiol.2372041887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chartrand-Lefebvre C, Lapointe R, Samson L, et al. Chest computed tomography screening in colorectal cancer patients. World J Surg 2009;33:1325–6. 10.1007/s00268-008-9891-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagtegaal ID, Quirke P. What is the role for the circumferential margin in the modern treatment of rectal cancer? J Clin Oncol 2008;26:303–12. 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hölzel D, Eckel R, Emeny RT, et al. Distant metastases do not metastasize. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2010;29:737–50. 10.1007/s10555-010-9260-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.