Abstract

Objective

Research has suggested that physicians’ gut feelings are associated with parents’ concerns for the well-being of their children. Gut feeling is particularly important in diagnosis of serious low-incidence diseases in primary care. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine whether empathy, that is, the ability to understand what another person is experiencing, relates to general practitioners’ (GPs) use of gut feelings. Since empathy is associated with burn-out, we also examined whether the hypothesised influence of empathy on gut feeling use is dependent on level of burn-out.

Design

Cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Participants completed the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy and The Maslach Burnout Inventory.

Setting

Primary care.

Participants

588 active GPs in Central Denmark Region (response rate=70%).

Primary outcome measures

Self-reported use of gut feelings in clinical practice.

Results

GPs who scored in the highest quartile of the empathy scale had fourfold the odds of increased use of gut feelings compared with GPs in the lowest empathy quartile (OR 3.99, 95% CI 2.51 to 6.34) when adjusting for the influence of possible confounders. Burn-out was not statistically significantly associated with use of gut feelings (OR 1.29, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.83), and no significant interaction effects between empathy and burn-out were revealed.

Conclusions

Physician empathy, but not burn-out, was strongly associated with use of gut feelings in primary care. As preliminary results suggest that gut feelings have diagnostic value, these findings highlight the importance of incorporating empathy and interpersonal skills into medical training to increase sensitivity to patient concern and thereby increase the use and reliability of gut feeling.

Keywords: clinical decision-making, early diagnosis, empathy, general practice, self-report

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Focus on primary care where diagnosis of serious low-incidence diseases is one of the challenges.

Use of validated scales for measuring physician empathy and burn-out.

High response rate.

The cross-sectional design makes causality difficult to determine.

Inclusion of hard-to-measure variables, such as physician empathy and use of gut feelings.

Introduction

General practitioners (GPs) sometimes base clinical decisions on their intuition or gut feelings. A limited number of studies have examined the diagnostic value of gut feelings and have shown significant and promising results. One study found a sensitivity of GPs’ gut feelings on 62% and a specificity on 97% regarding serious infections in children.1 Two other studies have reported positive predictive values (PPVs) of GPs gut feelings on 3%–35% concerning diagnoses of cancer.2 3 These PPVs are comparable or substantial higher than the PPVs of most cancer alarm symptoms presented in primary care, which are mostly below 3%.4

Stolper et al described two types of gut feeling in GPs: a ‘sense of alarm’ defined as an uneasy feeling indicating concerns about a possible adverse outcome, even though specific indications are lacking and a ‘sense of reassurance’ defined as a feeling of security about the management of a patient’s problem, even though the diagnosis may be uncertain.5 6 In models of diagnostic reasoning, intuition and analysis are often described as two modes of cognition, which can be placed at the ends of a continuum.7 Intuition comprises automatic, unconscious reasoning requiring low effort (system 1 decision-making), whereas analysis comprises controlled, conscious reasoning requiring high effort (system 2 decision-making).8 There seems to be consensus that gut feelings belong to the intuition end of the reasoning continuum, but the emphasis on lack of specific indications or objective arguments regarding in the sense of alarm as described in the Stolper definition6 is less clear in studies of gut feelings. For instance, in studies of gut feelings among emergency physicians, potential red flag vital signs were included in assessment of patients.8 9 Moreover, in another study, red flag symptoms such as palpable tumours were reported to be triggers of gut feelings.2 We cannot rule out that the physician has a gut feeling, but in such cases the clinical decision-making will probably also be based on conscious, rule-based reasoning saying that palpable tumours could potentially be malignant. One study of children examined for serious infections explicitly approached gut feelings as an intuitive feeling, which could arise despite that the clinical impression suggested a non-serious illness and found that parents’ worry was an important trigger of GPs’ gut feelings in children with no red flag symptoms.1 Thus, parental concern was registered in 33% of cases were gut feeling was present despite that the clinical impression was that of a non-serious illness and in only 2% of similar non-serious cases where gut feeling was absent.

It varies greatly to what extent the individual GP uses gut feelings.2 This might suggest that the use of gut feelings relate to the GP’s personality.6 Insofar the emotional state of the patient or his/her relatives is a trigger of gut feelings as proposed by the study above, physician empathy might be a determinant of the use of gut feelings. There is disagreement about the definition of empathy. In the medical context, empathy is often considered as a cognitive quality encompassing an understanding of the patient’s experience and concerns and an ability to communicate this understanding and an intention to help.10 However, in other areas the emotional feeling is the focal point in the definition of empathy and empathy is considered as an effective response to the emotions of others.11

Some GPs will congenitally be less empathic than others, but one group of GPs may initially have possessed good empathic skills which have then later on been reduced due to burn-out, which has been referred to as an ‘empathy killer’.12 Burn-out is a psychological construct defined as a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job and is characterised by emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation (cynicism) and a subjective experience of decreased personal accomplishment.13 Burn-out seems to be associated with empathy in a complex, bidirectional manner.12 Thus, burn-out has been associated with low levels of empathy.14 On the other side, deficits in perspective taking appear to be a risk factor for burn-out, whereas increased perspective taking and empathic concern seem to be protective against burn-out.15 16

On this background, we hypothesised that GPs who report high levels of empathy report higher use of gut feelings in their clinical work and that this hypothesised effect of empathy on use of gut feelings depends on the presence of burn-out.

Methods

Setting

GPs in Denmark are independent contractors with the regional health authorities. The patient list size is on average 1550 patients per GP including children. All Danish citizens are assigned a unique personal identification number, the civil registration number, by which information from numerous nationwide registers in Denmark can be linked.17

Study population

In January 2012, all 835 active GPs in Central Denmark Region were invited to participate in a survey on job satisfaction (the GP profile). GPs were identified by the Regional Registry of Health Providers. Non-respondents were sent a reminder after 4 and 13 weeks, and GPs were remunerated €50 for responding. In Denmark, it is customary to compensate doctors for their time when they participate in research projects.

Questionnaires: independent variables and effect modifier

Empathy was assessed by the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) consisting of 20 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale.18 Higher sum scores indicate higher levels of empathy. In this study, the empathy sum score was categorised into four groups based on its quartiles.

Burn-out was assessed by The Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS).13 The MBI-HSS has been used in more than 90% of empirical studies of burn-out in the world.19 The scale has been translated into Danish following standardised procedures. The MBI-HSS consists of 22 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale constituting three subscales: (1) emotional exhaustion (nine items), (2) depersonalisation (five items) and (3) personal accomplishment (eight items). Each subscale score is categorised as low or high based on normative population score.13 A high level of emotional exhaustion is defined as a score >26, and a high level of depersonalisation is defined as a score >9. Low personal accomplishment is defined as a score <34. Burn-out was defined as a high score on the emotional exhaustion subscale and/or a high score on the depersonalisation subscale.13

Both the JSPE and MBI-HSS were translated into Danish in accordance with WHO guidelines.20 The translation process included a forward translation and an expert panel back translation and pilot testing of translated version.

Single item: the outcome variable

A definition of gut feeling, based on Stolper’s work,21 was included in the questionnaire and was as follows: ‘a physician’s intuitive feeling that something is wrong with the patient although there is no apparent clinical indications for this, or a physician’s intuitive feeling that the strategy used in relation to the patient is correct, although there is uncertainty about the diagnosis’. The GPs were asked to rate how much they use gut feelings in their daily clinical work and the response was graded on a 5-point Likert scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘a very high degree’. The question was inspired by a former Danish study on use of gut feelings.22

According to Danish law, the study was not submitted to an ethical committee since questionnaire surveys do not require an ethical approval.

Analysis

The outcome variable (use of gut feelings) was assessed on an ordinal scale (from not at all to a very high degree). After confirming that the proportional odds assumption was met, ordered logistic regression was used to examine associations between empathy, burn-out dimensions and use of gut feelings. Associations were calculated as ORs. To test for an association between empathy and use of gut feeling and whether the association was dependent on presence of burn-out (ie, interaction effect), one hierarchical ordered logistic regression analysis was performed. In the first step (model 1), sex, age, practice organisation and burn-out were included as covariates. In the second step (model 2), the interaction variables between empathy quartiles and burn-out were included. To assist interpretation of results, predicted probabilities for empathy quartiles were calculated. As a sensitivity analysis, three separate hierarchical ordered logistic regression analyses were performed adjusting for the three burn-out dimensions (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal accomplishment) individually. We handled missing data by listwise deletion. The 95% CIs for ratios were calculated and P values of 5% or less were considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using STATA V.13.

Results

Among the 835 invited GPs, 588 (70%) completed the question about use of gut feelings in their clinical practice. Among the 588 included GPs, there was a slight predominance of male GPs (52%) and the majority of GPs worked in group practices (76%). One GP reported not to use gut feelings and this GP was added to the 20 (3%) GPs who reported that they used gut feelings to a low degree. Respectively, 254 (43%), 211 (36%) and 102 (17%) reported that they used gut feelings to some degree, a high degree and a very high degree. Sociodemographic characteristics of the 588 included GPs are depicted in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and scores on burn-out dimensions and empathy by gut feeling categories

| All, N=588 (100%) |

Use of gut feelings | ||||

| To a low degree, N=21 (3.6%) |

To some degree, N=254 (43.2%) |

To a high degree, N=211 (35.9%) |

To a very high degree, N=102 (17.3%) |

||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 278 (47.3) | 5 (23.8) | 126 (50.2) | 94 (44.8) | 53 (52.0) |

| Male | 306 (52.0) | 16 (76.2) | 125 (49.8) | 116 (55.2) | 49 (48.0) |

| Practice organisation | |||||

| Group | 445 (75.7) | 15 (71.4) | 207 (81.5) | 157 (74.4) | 66 (64.7) |

| Solo | 143 (24.3) | 6 (28.6) | 47 (18.5) | 54 (25.6) | 36 (35.3) |

| Age of GPs (years) | |||||

| <40 | 39 (6.6) | 2 (9.5) | 19 (7.5) | 14 (6.6) | 4 (3.9) |

| 40–49 | 183 (31.1) | 3 (14.3) | 75 (29.5) | 66 (31.3) | 39 (38.2) |

| 50–59 | 226 (38.4) | 9 (42.9) | 98 (38.6) | 78 (37.0) | 41 (40.2) |

| >60 | 138 (23.5) | 7 (33.3) | 61 (24.0) | 52 (24.6) | 18 (17.7) |

| Empathy | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 154 (26.2) | 12 (57.1) | 83 (32.7) | 46 (21.8) | 13 (12.8) |

| Second quartile | 145 (24.7) | 4 (19.1) | 70 (27.6) | 49 (23.2) | 22 (21.6) |

| Third quartile | 129 (21.9) | 0 (0.0) | 53 (20.9) | 51 (24.2) | 25 (24.5) |

| Highest quartile | 129 (21.9) | 3 (14.3) | 35 (13.8) | 53 (25.1) | 38 (37.3) |

| Burn-out | |||||

| No burn-out | 441 (75.0) | 20 (95.2) | 192 (75.6) | 146 (69.2) | 83 (81.4) |

| Burn-out | 147 (25.0) | 1 (4.8) | 62 (24.4) | 65 (30.8) | 19 (18.6) |

| Emotional exhaustion | |||||

| Low | 479 (81.5) | 19 (90.5) | 212 (83.5) | 164 (77.7) | 84 (82.4) |

| High | 102 (17.4) | 1 (4.8) | 39 (15.4) | 46 (21.8) | 16 (15.7) |

| Depersonalisation | |||||

| Low | 503 (85.5) | 19 (90.5) | 219 (86.2) | 172 (81.5) | 93 (91.2) |

| High | 81 (13.8) | 1 (4.8) | 33 (13.0) | 38 (18.0) | 9 (8.8) |

| Personal accomplishment | |||||

| High | 377 (64.1) | 14 (66.7) | 157 (61.8) | 133 (63.0) | 73 (71.6) |

| Low | 201 (34.2) | 6 (28.6) | 92 (36.2) | 76 (36.0) | 27 (26.5) |

Values may not total 100 due to rounding or missing information.

GPs, general practitioners.

The empathy sum score correlated negatively with emotional exhaustion (r=−0.13; P=0.003), depersonalisation (r=−0.24; P<0.001) and positively with personal accomplishment (r=0.43; P<0.001).

Table 2 depicts associations between gut feelings and sociodemographic factors, the three burn-out dimensions and empathy. A linear relationship between empathy and use of gut feelings was revealed when adjusting for sex, age, practice organisation and burn-out. Thus, compared with GPs in the lowest empathy quartile, GPs in the highest quartile had fourfold the likelihood of increased use of gut feelings (ORmodel 1 3.99, 95% CI 2.51 to 6.34).

Table 2.

Summary of a hierarchical ordered logistic regression analysis with gut feeling categories used as outcome

| Model 1* | Model 2† | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Males versus females | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.24) | 0.473 | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.23) | 0.435 |

| Age | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | 0.101 | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | 0.107 |

| Practice organisation | ||||

| Solo practice versus group practice | 1.82 (1.23 to 2.69) | 0.003 | 1.86 (1.25 to 2.75) | 0.002 |

| Empathy‡ | ||||

| Second quartile versus first | 1.76 (1.13 to 2.74) | 0.012 | 1.71 (0.99 to 2.94) | 0.054 |

| Third quartile versus first | 2.47 (1.57 to 3.89) | <0.001 | 2.29 (1.33 to 3.93) | 0.003 |

| Fourth quartile versus first | 3.99 (2.51 to 6.34) | <0.001 | 4.12 (2.38 to 7.11) | <0.001 |

| Burn-out | ||||

| Burned-out versus not burned-out | 1.29 (0.90 to 1.83) | 0.165 | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.34) | 0.555 |

| Empathy quartiles x burn-out | ||||

| Second quartile versus first x burn-out | 1.10 (0.43 to 2.83) | 0.840 | ||

| Third quartile versus first x burn-out | 1.35 (0.50 to 3.66) | 0.560 | ||

| Fourth quartile versus first x burn-out | 0.84 (0.30 to 2.30) | 0.728 | ||

*Model 1 included sex, age, practice organisation and burn-out as covariates.

†Model 2 included the same covariates as model 1 besides interaction variables between empathy quartiles and burn-out.

‡Empathy quartiles were represented as three dummy variables with first (lowest) quartile serving as the reference group.

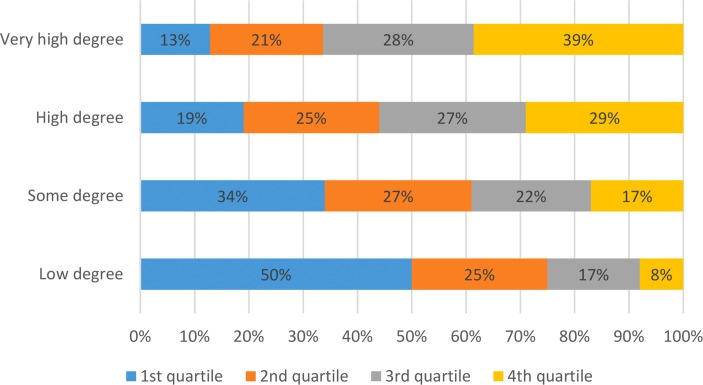

Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of being in each of the four gut feeling categories in relation to level of empathy score. The pattern of those in the lowest and highest quartiles of the empathy sum score is opposite. Thus, 50% of those in the lowest quartile of the empathy sum score uses gut feelings to a low degree and only 13% of participants in this group uses gut feelings to a very high degree. Opposite this, only 8% of those in the highest quartile of the empathy sum score uses gut feelings to a low degree whereas 39% of this group uses gut feelings to a very high degree. Burn-out was not significantly associated with use of gut feelings (ORmodel 1 1.29, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.83) and the results did not reveal a significant interaction between burn-out and empathy on the use of gut feelings (table 2). Including each of the three burn-out dimensions individually in the sensitivity analysis did not reveal a main effect of any of the three burn-out dimensions on use of gut feelings (data not shown; ORhigh emotional exhaustion versus low 1.41, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.11; ORhigh depersonalisation versus low 1.32, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.04; ORlow personal accomplishment versus high 1.21, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.72). Including each of the three burn-out dimensions individually did neither support a moderating effect of any of the three burn-out dimensions (data not shown; P values 0.336–0.923).

Figure 1.

The predicted share of general practitioner in the four gut feeling categories (use of gut feeling to a low, some, high or very high degree) based on their empathy score divided into quartiles.

Solo GPs had significantly greater likelihood of increased use of gut feelings compared with GPs in group practices (ORmodel 2 1.86, 95% CI 1.25 to 2.75).

Discussion

Main findings

This study supported our hypothesis with a robust linear association between increased empathy score and increased use of gut feelings, even when adjusting for the influence of possible confounders such as sex, age, practice organisation and burn-out. Compared with GPs in the lowest empathy quartile, GPs in the highest quartile reported fourfold increased use of gut feelings. The predicted probability of using gut feelings to a very high degree was 28% for GPs scoring in the highest quartile of the empathy scale and only 9% of GPs scoring in the lowest quartile of the scale. The results of the study did neither support an association between burn-out and use of gut feelings nor that the influence of empathy on use of gut feelings was significantly associated with burn-out.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of the present study is the use of validated scales for measuring physician empathy and burn-out. Moreover, the response rate was relatively high. One limitation of the study is the cross-sectional design based on which causality cannot be determined. The ability to display empathy is not easily measurable by self-report, and the JSPE actually assesses the physician’s attitude to empathy more than the actual empathic ability, probably because it is mainly based on a cognitive approach to empathy.18 To our knowledge, it has not been examined whether the physician’s attitude to empathy correlates with his/her actual capacity to understand what another person is experiencing. Therefore, we cannot exclude that the results of this study reveal an association between a positive attitude to empathy and a positive attitude to use of gut feelings rather than an association between empathic abilities and use of gut feelings. Furthermore, the assessment of use of gut feelings was based on a single item, which was developed for use in a previous study.22 The item was based on a consensus statement on gut feelings obtained by Stolper et al5 in a Delphi procedure and pilot-tested, but not further validated. After our data were collected, a promising 11-item gut feelings questionnaire was published.21

Comparisons with existing literature

In the literature, ‘pattern failure’ is often described as a trigger of gut feelings in primary care. According to Stolper et al, GPs are familiar with the normal pattern of their patient’s appearance, for example, the way the patient normally sits, speaks and looks, and when that normal pattern of appearance changes, it may be a trigger of gut feelings.6 Likewise, Van den Bruel et al noted that changes in the behaviour of the parents of the child, for example, an observation that the mother was unusually anxious compared with previous consultations, was an important trigger of gut feelings in primary care.1 The findings of our study do not contradict the ‘pattern failure’ as an explanation of what triggers gut feelings in primary care. Meanwhile, the emphasis on pattern failure as a trigger of gut feelings might not justify why physician empathy and use of gut feelings seem to be as strongly associated as revealed in this study. Stolper et al mention that bodily sensations often accompany gut feelings.23 The emotional sensations are seen as elicited by the positive or negative quality attached to the experience of for instance a sign, which do not fit into a familiar pattern of a patient, and play as such a guiding role for the GP.23 Although Stolper et al during a Delphi procedure to reach consensus on the understanding of gut feelings stressed that gut feelings are not about empathy towards the patient,5 it could be hypothesised that highly empathic GPs are more responsive towards their own affective, bodily sensations accompanying gut feelings. It could also be hypothesised that in some instances, gut feelings arise because the highly empathic GP consciously or unconsciously captures patient’s worry expressed through linguistic cues, body language, facial expressions and intonations. In this hypothesis, the affective bodily sensations are not seen as elicited by the gut feeling, but rather as a trigger of gut feelings. Embodied simulation theory describes how individuals understand others’ actions, emotions and sensations through mirror neurons, and has been proposed as a neurobiological basis for automatic, unconscious communication such as projective identification, empathy and transference–countertransference interactions.24 The hypothesised impact of embodied simulation on GPs’ gut feelings has to be further examined experimentally, since reliable data on this automatic, unconscious communication might not be retrieved through introspection and self-report.

Likewise, we need more knowledge concerning under which circumstances patient worry and patient intuition has credibility and significance.25

It has been suggested that medical students should be provided with cases that stimulate their use of intuition and be exposed to teaching which encourage instinctive clinical judgement in patient management and diagnosis.26 In line with this, discussing gut feelings in traineeship seems to be a favourable way to bring non-analytical reasoning into use for GP trainees.27 Based on findings from one study showing that relatives’ worries can trigger gut feelings1 and findings of the present study revealing an association between physician empathy and use of gut feelings, we suggest that the role of emotions in the doctor–patient relationship is emphasised within the medical school curriculum. It has been suggested that medical education seems to encourage students not to acknowledge emotions of patients.28 This view is supported by studies showing that the most common physician responses to patients’ expression of worry were biomedical questions, medical explanations and reassurance,29 and that when patients express negative emotions, the physicians’ responses were directed towards the emotional expression in only 32% of the cases.30 Since patient concern is often expressed indirectly through cues or clues, it would be relevant to examine whether increased sensitivity towards such clues could improve the diagnostic process.31 Studies have shown that when physicians respond to patients’ expressions of negative emotions with statements that allow for or explicitly encourage further discussion of emotion, then clinically relevant information is often elicited.30 Furthermore, a review concluded that opening up for patient emotions and providing empathic responses may be associated with positive patient outcomes such as reduced distress and increased patient adherence, cooperation and partnership building.31

We found no significant association between burn-out or any of the three burn-out dimensions and use of gut feelings. Certainly, burned-out GPs had approximately 30% increased likelihood of using gut feelings to a high level compared with GPs who were not burned-out, but the CIs were wide (0.90 to 1.83) suggesting some inconsistency concerning whether burn-out increases or decreases use of gut feelings in our sample. In line with this, the consequences of burn-out for GPs’ interpersonal skills are controversial and findings are mixed.32 33 For instance, the results of one study revealed no associations between GPs’ level of depersonalisation and their patient-rated interpersonal skills or observed patient-centredness,34 whereas another study revealed that GPs with high levels of exhaustion and depersonalisation were more likely to provide opportunities to discuss mental health problems in the consultation compared with GPs with low levels of exhaustion and depersonalisation.35 The mixed findings may partially be explained by gender differences. Thus, in one study, exhausted female GPs had shorter consultations and were less patient-centred than non-exhausted female GPs whereas exhausted male GPs had longer consultations and were more patient-centred than non-exhausted male GPs.36 The findings of the present study revealing that empathy, but not burn-out, is associated with the use of gut feelings might suggest that the use of gut feelings among GPs is more dependent on personality traits than on the current state of the physician. This agrees to results of a focus group study in which GPs themselves experienced that personality traits such as the ability to tolerate risk and uncertainty influenced the way that they handled gut feelings.6 A link between personality traits and use of gut feelings raises the question about whether the use of gut feelings can be taught or is an innate ability.26 Although gut feelings appear to relate to certain personality traits, it is important to stress that the one condition may not be responsible for the other and that the link may not be maintained in the future if teaching of gut feeling was included in the medical school curriculum.

We did not find that age of the GP was associated with use of gut feelings. This contradicts with the findings of other studies in which gut feeling was found either more frequently in less experienced physicians compared with senior physicians1 or more frequently by experienced than by less experienced physicians.37 Compared with these studies, the participants in our study might have been more homogeneous since virtually all physicians in our study were specialists in general medicine and as such quite experienced. Moreover, we examined used of gut feelings in general whereas the other two studies examined the use of gut feeling with reference to specific patient cases. Gut feeling has been described as an intuitive feeling that results from unconscious reasoning and comes with experience.23 Therefore, the results showing less use of gut feeling with increasing experience may appear peculiar.1 Meanwhile, as stated by the authors, the triggers of a gut feeling may be processed as part of the conscious diagnostic reasoning in the experienced physician and as preconscious reasoning in the less experienced physician. In this study, the sensitivity and specificity of gut feeling was the same in the experienced and less experienced physicians,1 but the results of another study revealed that the PPV of cancer-related gut feeling increased with 3% for every year a GP becomes older.2 Taken together, more research is needed to determine both the understanding, use and precision of gut feeling in experienced and less experienced physicians.

Solo GPs had significantly greater likelihood of increased use of gut feelings compared with GPs in group practices. This finding may reflect that familiarity with the patient is often reported to increase reliance on gut feelings.6 Since patient lists are sometimes shared among GPs in group practices, their familiarity with the individual patient may be reduced compared with solo GPs who often have long-lasting relationships with their patients.

Conclusions and implications

There was a positive association between physician empathy and reported use of gut feelings in primary care. Burn-out was neither associated with use of gut feelings nor did it act as an effect moderator on the relationship between empathy and use of gut feelings. We hypothesise that transfer of patient concern to the GP may be one of the triggers of gut feelings and more research is needed to determine under which circumstances patient worries can be used as a reliable tool in the diagnostic process. The use of gut feelings, empathy and interpersonal skills should be incorporated into specialty training to support the use of patient emotions as a deliberate tool in the diagnostic process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christina Maar Andersen for her help during data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: AFP, MLI and PV conceptualised the study. AFP analysed the data and MLI and PV took part in the interpretation of results. AFP wrote the original draft and AFP, MLI and PV contributed to the editing and reviewing of the draft.

Funding: The Centre for Cancer Diagnosis in Primary Care is funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Danish Cancer Society. The project was further supported financially by the Committee of Quality and Supplementary Training (KEU) in the Central Denmark Region (grant no: 1-30-72-207-12).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal no: 2011-41-6609).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for access to data should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Van den Bruel A, Thompson M, Buntinx F, et al. . Clinicians' gut feeling about serious infections in children: observational study. BMJ 2012;345:e6144 10.1136/bmj.e6144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donker GA, Wiersma E, van der Hoek L, et al. . Determinants of general practitioner’s cancer-related gut feelings-a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012511 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hjertholm P, Moth G, Ingeman ML, et al. . Predictive values of GPs' suspicion of serious disease: a population-based follow-up study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e346–e353. 10.3399/bjgp14X680125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamilton W. Cancer diagnosis in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:121–8. 10.3399/bjgp10X483175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stolper E, Van Royen P, Van de Wiel M, et al. . Consensus on gut feelings in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:66,2296–10. 10.1186/1471-2296-10-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolper E, van Bokhoven M, Houben P, et al. . The diagnostic role of gut feelings in general practice. A focus group study of the concept and its determinants. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:17,2296-10–17. 10.1186/1471-2296-10-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond KR, Hamm RM, Grassia J, et al. . Direct comparison of the efficacy of intuitive and analytical cognition in expert judgment, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man. and Cybernetics 1987;17:753–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiswell J, Tsao K, Bellolio MF, et al. . "Sick" or "not-sick": accuracy of System 1 diagnostic reasoning for the prediction of disposition and acuity in patients presenting to an academic ED. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:1448–52. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabrera D, Thomas JF, Wiswell JL, et al. . Accuracy of ’My Gut Feeling:' Comparing System 1 to System 2 Decision-Making for Acuity Prediction, Disposition and Diagnosis in an Academic Emergency Department. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:653–7. 10.5811/westjem.2015.5.25301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hojat M, DeSantis J, Gonnella JS. Patient Perceptions of Clinician’s Empathy: Measurement and Psychometrics. J Patient Exp 2017;4:78–83. 10.1177/2374373517699273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robieux L, Karsenti L, Pocard M, et al. . Let’s talk about empathy!. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:59–66. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenasni F, Boujut E, Woerner A, et al. . Burnout and empathy in primary care: three hypotheses. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:346–7. 10.3399/bjgp12X652193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory manual. (3rd) Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuguero O, Ramon Marsal J, Esquerda M, et al. . Association between low empathy and high burnout among primary care physicians and nurses in Lleida, Spain. Eur J Gen Pract 201723:4–10. 10.1080/13814788.2016.1233173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamothe M, Boujut E, Zenasni F, et al. . To be or not to be empathic: the combined role of empathic concern and perspective taking in understanding burnout in general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2014;15:15,2296 10.1186/1471-2296-15-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Picard J, Catu-Pinault A, Boujut E, et al. . Burnout, empathy and their relationships: a qualitative study with residents in General Medicine. Psychol Health Med 2016;21:354–61. 10.1080/13548506.2015.1054407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, et al. . Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:1563–9. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. . The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005;19:192–207. 10.1080/02678370500297720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. 2015.

- 21.Stolper CF, Van de Wiel MW, De Vet HC, et al. . Family physicians' diagnostic gut feelings are measurable: construct validation of a questionnaire. BMC Fam Pract 2013;14:1,2296 10.1186/1471-2296-14-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingeman ML, Christensen MB, Bro F, et al. . The Danish cancer pathway for patients with serious non-specific symptoms and signs of cancer-a cross-sectional study of patient characteristics and cancer probability. BMC Cancer 2015;15:421,015–1424. 10.1186/s12885-015-1424-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stolper E, Van de Wiel M, Van Royen P, et al. . Gut feelings as a third track in general practitioners' diagnostic reasoning. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:197–203. 10.1007/s11606-010-1524-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallese V, Eagle MN, Migone P. Intentional attunement: mirror neurons and the neural underpinnings of interpersonal relations. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 2007;55:131–75. 10.1177/00030651070550010601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buetow SA, Mintoft B. When should patient intuition be taken seriously? J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:433–6. 10.1007/s11606-010-1576-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins M, O’Donnell L. Gut feeling: Can it be taught? Med Teach 2015;1:792 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1042441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stolper CF, Van de Wiel MW, Hendriks RH, et al. . How do gut feelings feature in tutorial dialogues on diagnostic reasoning in GP traineeship? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2015;20:499–513. 10.1007/s10459-014-9543-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapiro J. Perspective: Does medical education promote professional alexithymia? A call for attending to the emotions of patients and self in medical training. Acad Med 2011;86:326–32. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182088833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, et al. . "Could this be something serious?" Reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients' expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1731–9. 10.1007/s11606-007-0416-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams K, Cimino JE, Arnold RM, et al. . Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:44–50. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finset A. "I am worried, Doctor!" Emotions in the doctor-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:359–63. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trollope-Kumar K. Do we overdramatize family physician burnout?: NO. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:731735–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay M. Do we overdramatize family physician burnout?: YES. Can Fam Physician 2012;58:730734–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orton P, Orton C, Pereira Gray D. Depersonalised doctors: a cross-sectional study of 564 doctors, 760 consultations and 1876 patient reports in UK general practice. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000274 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zantinge EM, Verhaak PF, de Bakker DH, et al. . Does burnout among doctors affect their involvement in patients' mental health problems? A study of videotaped consultations. BMC Fam Pract 2009;10:60,2296 10.1186/1471-2296-10-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orton PK, Pereira Gray D. Factors influencing consultation length in general/family practice. Fam Pract 2016;33:529–34. 10.1093/fampra/cmw056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woolley A, Kostopoulou O. Clinical intuition in family medicine: more than first impressions. Ann Fam Med 2013;11:60–6. 10.1370/afm.1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.