Abstract

Introduction

There is now substantial evidence of a social gradient in bone health. Social stressors, related to socioeconomic status, are suggested to produce an inflammatory response marked by increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Here we focus on the particular role in the years before the achievement of peak bone mass, encompassing childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. An examination of such associations will help explain how social factors such as occupation, level of education and income may affect later-life bone disorders. This paper presents the protocol for a systematic review of existing literature regarding associations between socioeconomic factors and proinflammatory cytokines in those aged 6–30 years.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct a systematic search of PubMed, OVID and CINAHL databases to identify articles that examine associations between socioeconomic factors and levels of proinflammatory cytokines, known to influence bone health, during childhood, adolescence or young adulthood. The findings of this review have implications for the equitable development of peak bone mass regardless of socioeconomic factors. Two independent reviewers will determine the eligibility of studies according to predetermined criteria, and studies will be assessed for methodological quality using a published scoring system. Should statistical heterogeneity be non-significant, we will conduct a meta-analysis; however, if heterogeneity prevent numerical syntheses, we will undertake a best-evidence analysis to determine whether socioeconomic differences exist in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines from childhood through to young adulthood.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be a systematic review of published data, and thus ethics approval is not required. In addition to peer-reviewed publication, these findings will be presented at professional conferences in national and international arenas.

Keywords: inflammatory markers, cytokines, socioeconomic factors, systematic review, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will provide a comprehensive assessment of the existing literature regarding associations between socioeconomic factors and levels of proinflammatory cytokines known to influence bone, in ages from childhood (6 years) to young adulthood (30 years).

Study selection and data extraction will be performed by one author and confirmed by a second, and assessment of methodology will be conducted independently by two authors.

The findings will have implications for research into the possible role of inflammation as a mediator between socioeconomic factors and bone health in later life.

Possible limitations of this review include heterogeneity due to variation in the (1) measurement of socioeconomic factors, (2) study populations, particularly with respect to age ranges, and the impact of heritable factors and race/ethnicity on associations and (3) methods used to measure proinflammatory cytokine levels.

Introduction

A social gradient in the majority of chronic, non-communicable diseases has been well documented. In addition, there is now considerable evidence of a social gradient in bone health, whereby worsening levels of social disadvantage is associated with lower bone mineral density (BMD) and increased fracture risk, independent of age and other clinical risk factors, such as body mass index, dietary factors, smoking and alcohol consumption.1–5 However, the potential causal mechanism(s) underpinning the social gradient in bone health are not well understood.

Recently, we conceptualised a role for inflammation in the relationship between social disadvantage and low BMD and the associated risk of fracture in adults.6 We postulated an epigenetic process across the life course, whereby social stressors resulted in heightened oxidative stress and increased inflammatory reactivity, with subsequent effects on phenotypic expression of disease risk. One indication of this process would be an association between social disadvantage and heightened levels of inflammation during the years of infancy, childhood and early adulthood, that is, before the attainment of peak bone mass. Such an association would have a particularly marked effect on BMD for the remainder of life and hence on the risk for osteoporosis and fracture in later life. Across the lifespan, proinflammatory biomarkers known to be associated with bone accrual are the cytokines interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, C-reactive protein (CRP) and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα).

This systematic review protocol proposes to collate and synthesise the available evidence regarding whether social stressors during childhood, adolescence and early adult life may increase the levels of proinflammatory cytokines. The need for this review is imperative, as there appears some contradictory and complex associations, which will impede progress towards understanding early life precursors for poorer bone health in later life. For instance, one study of Canadian schoolchildren found that the effects of IL-6 levels vary with the trajectory of socioeconomic status (SES), measured as parent-reported housing data during childhood and that a number of interactions between social and health factors affected levels of IL-6.7 Another study, of Canadian adolescents, found that SES as measured by family income moderated the effect of ‘family chaos’ on some proinflammatory biomarkers (IL-1A, IL-6, IL-8 and a composite measure of all cytokines measured), but not all (CRP, IL-10).8

Hence, there appears to be a prima facie rationale for systematically examining past work on associations between levels of proinflammatory cytokines and socioeconomic factors in the life course from childhood up to and including young adulthood. Here, we present the protocol for a systematic review of this literature, which adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol (PRISMA-P) guidelines.9

Objectives

This systematic review will:

Identify published studies examining the associations between socioeconomic factors and the levels of proinflammatory cytokines known to influence bone health, in ages from childhood (6 years) up to and including young adulthood (30 years).

Evaluate the methodological quality of all eligible studies according to a previously employed scoring system.10 11

Analyse the combined level of evidence of all studies and conduct a subgroup analysis to examine the findings from studies deemed to be of high methodological quality (determined by quality assessment score above the median) to determine if any bias is observed.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

The criteria for inclusion in this review will be: full-text articles published in English that are epidemiological cohort, case–control and/or cross-sectional studies and which examine associations between socioeconomic factors measured at the individual or area level and proinflammatory cytokines. A study will be eligible if it examines any, or all, of the proinflammatory cytokines commonly known to be associated with bone accrual: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CRP and TNFα.

Grey literature, opinion pieces, commentaries, unpublished theses and conference presentations will be excluded. Furthermore, given that the purpose of this review is to ascertain whether differences exist in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines across socioeconomic factors, randomised controlled trials (RCT) will be excluded unless baseline data, or data from the control arm of RCTs, pertain to proinflammatory cytokines levels prior to intervention. In that instance, data from the control arm would be equivalent to a cohort study and would thus be included.

Socioeconomic factors

For this review, the prime variables of interest are socioeconomic factors: these may be measured at the individual level, including, but not limited to income, education, occupation, employment status, type of residence and marital status. Socioeconomic factors may also be measured at the household or area level, and/or include composite measures of socioeconomic parameters: these composite measures may be based on country-specific or region-specific administrative boundaries including government or statistical areas or census collection districts, among others.

Proinflammatory cytokine measurement

The cytokines to be included are IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CRP and TNFα, which are known to have effects on bone health.6 12 Included studies may have measured a different range of biomarkers. It is also important to account for which of the two differing general methods for measuring cytokine levels that a study has used. Some studies measure circulating cytokine levels in vivo, while others measure cytokine levels in vitro which involves the stimulation of white blood cells by one of a range of agents.7 As these methods will give differing results for the same participants, in the case of a meta-analysis being performed, this review will follow the methods of Steptoe et al whereby studies measuring circulating levels and stimulated levels were investigated separately.13

Age

Eligible studies will be restricted to those examining participants who are children, adolescents or in young adults, which, according to Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) encompasses those aged from 6 years up to and including 30 years of age (MeSH categories ‘child’, ‘adolescent’ and ‘young adult’). The rationale for this age range is to examine the particular associations between cytokine levels and socioeconomic factors before the achievement of peak bone mass. Peak bone mass is defined as the achievement of the highest possible level of stable bone density14: estimation of the age which peak bone mass occurs depends on the skeletal site and within individuals by a range of hereditable and environmental factors; however, total bone mass is considered to peak between the early to late 20s.14

Information sources and search strategy

We will perform a computer-generated search strategy using databases for medical, health and social sciences (PubMed, OVID and CINAHL) to identify relevant literature, with no limits set on the date of publication. Standard medical subject headings (MeSH) and keywords will be applied to capture the broadest range of publications to compare against the predetermined inclusion criteria. The full search string to be applied will be: ‘(Cytokines OR interleukin OR C-reactive protein) AND (socioeconomic factors OR socioeconomic status OR poverty OR social class OR income OR education OR residence OR occupation OR marital status) AND (child OR adolescent OR young adult OR youth)’. Relevant truncation will be used as appropriate to each database. Duplicate articles will be identified and removed using the relevant functionality of the reference management application endnote. Reference lists of relevant studies that fulfil the eligibility criteria will be independently hand searched. Study selection and data extraction will be performed by one author (NJF) and confirmed by a second (SLB-O), where another opinion is necessary to address any eligibility-related or data-related disagreement, this will be independently provided by a third author (GD).

Assessment of methodological quality of included articles

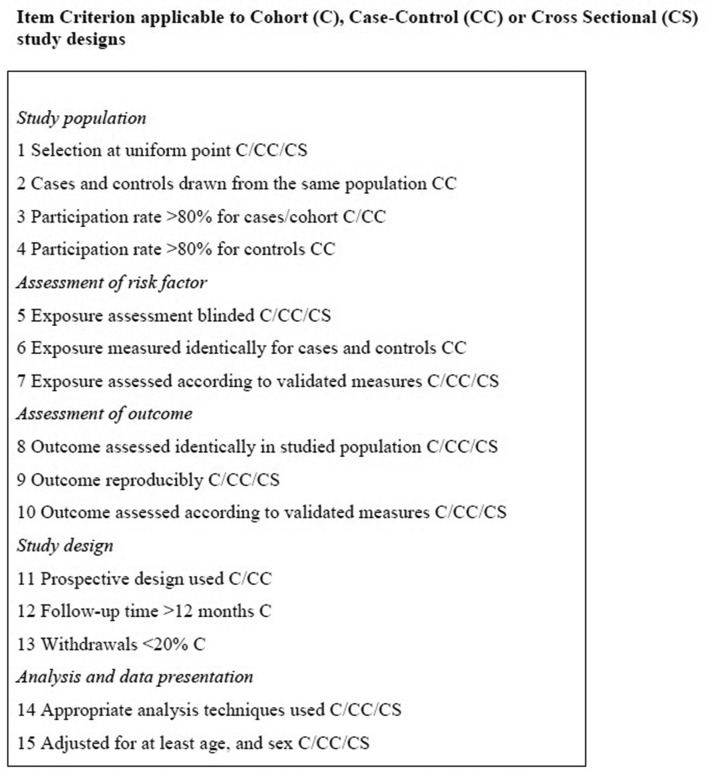

The methodological quality of included studies will be independently investigated by two reviewers (NJF and DG) using the assessment and scoring system of Lievense and colleagues,10 11 as previously employed for other systematic reviews in the musculoskeletal field.15–17 That scoring system evaluates the methodological quality of included studies in the following way. For each design-specific criteria that a study meets (figure 1), it will receive a score of 1 and otherwise 0. Scores will be presented as a percentage of the maximum possible score for each particular study design, whereby cohort studies are determined to be the optimum design due to their inherent qualities, followed by case–control and cross-sectional study designs.

Figure 1.

Criteria list for the assessment of methodological quality, modified from Lievense et al10 11

In the case that any discrepancies in scores cannot be reconciled by the scorers, a third reviewer will make a final judgement at a single consensus meeting (GD). To assess relative methodological quality, studies will be categorised as high quality if the percentage score is above the median of all scores.

Presenting and reporting results and data synthesis

Details of the protocol for this systematic review have been registered with PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42016045271). The results of this review will be presented according to the framework of the PRISMA-P reporting guidelines.9 The process of study selection and reasons for the exclusion of any studies will be outlined in a Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses diagram, including observational studies.18 The following key information will be extracted from papers and included in the review: author(s), year of study, sample size, study design, country from where the sample was drawn (and region, state or district if available); population description, including age ranges, description of socioeconomic factors, including the measurement and tool and the specific proinflammatory cytokines and any other markers assessed and the methods used to measure them. A description of the modelling methods used by each study including the factors accounted for in each model, specifically anti-inflammatory biomarkers, the statistical results and a summary of the findings will also be provided.

We will conduct a meta-analysis, controlling for heterogeneity, if statistically appropriate. Should statistical heterogeneity preclude a numerical synthesis, we will conduct a best-evidence synthesis to assess the level of evidence from ‘strong’ to ‘no evidence’, based on the published methods of Lievense et al10 11 (table 1) and as previously published in the musculoskeletal field.15–17

Table 1.

Criteria for ascertainment of evidence level for best-evidence synthesis, adapted from Lievense et al10 11

| Level of evidence | Criteria for inclusion in best-evidence synthesis |

| Strong evidence | Generally consistent findings in:

|

| Moderate evidence | Generally consistent findings in:

|

| Limited evidence | Generally consistent findings in:

|

| Conflicting evidence | Inconsistent findings in <75% of the studies |

| No evidence | No studies could be found |

Ethics and dissemination

As this review will be using published data, it does not require ethical clearance. We will adhere to standard ethical and governance standards regarding data management and the presentation and discussion of our findings. Findings of this systematic review will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed scientific journal and will be presented and discussed at relevant national and international conferences and meetings.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that proposes to investigate the associations between socioeconomic factors and levels of proinflammatory cytokines in children, adolescents and young adults. Given the role of proinflammatory cytokines on bone, this information may contribute the evidence base regarding how social factors during early life may influence the development of musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoporosis later in life.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: NJF, GD and SLB-O conceptualised the research question for this protocol. NJF and SLB-O confirmed the e-search strategy and developed the methodological processes. NJF and SLB-O drafted the manuscript. SLB-O is the guarantor of the review. All the authors read and approved the final version, guaranteed the protocol, edited and revised the research question. All authors contributed to the development of the e-search strategy, edited, revised and approved the methodological processes and edited and contributed to the writing of this paper.

Funding: SLB-O is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC (of Australia)) Career Development Fellowship (1107510).

Competing interests: SLB-O has received speaker fees from Amgen. GD has received speaker fees from Amgen, Sanofi, and Lilly Australia.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Brennan SL, Henry MJ, Wluka AE, et al. BMD in population-based adult women is associated with socioeconomic status. J Bone Miner Res 2009;24:809–15. 10.1359/jbmr.081243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan SL, Henry MJ, Wluka AE, et al. Socioeconomic status and bone mineral density in a population-based sample of men. Bone 2010;46:993–9. 10.1016/j.bone.2009.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan SL, Holloway KL, Williams LJ, et al. The social gradient of fractures at any skeletal site in men and women: data from the Geelong Osteoporosis Study Fracture Grid. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1351–9. 10.1007/s00198-014-3004-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crandall CJ, Han W, Greendale GA, et al. Socioeconomic status in relation to incident fracture risk in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1379–88. 10.1007/s00198-013-2616-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira CM, Economou T, Bailey T, et al. The interactions between municipal socioeconomic status and age on hip fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:489–98. 10.1007/s00198-014-2869-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennan-Olsen SL, Page RS, Berk M, et al. DNA methylation and the social gradient of osteoporotic fracture: A conceptual model. Bone 2016;84:204–12. 10.1016/j.bone.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azad MB, Lissitsyn Y, Miller GE, et al. Influence of socioeconomic status trajectories on innate immune responsiveness in children. PLoS One 2012;7:e38669 10.1371/journal.pone.0038669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreier HM, Roy LB, Frimer LT, et al. Family chaos and adolescent inflammatory profiles: the moderating role of socioeconomic status. Psychosom Med 2014;76:460–7. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lievense A, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Verhagen A, et al. Influence of work on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review. J Rheumatol 2001;28:2520–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhagen AP, et al. Influence of obesity on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2002;41:1155–62. 10.1093/rheumatology/41.10.1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riancho JA, Brennan-Olsen SL. The epigenome at the crossroad between social factors, inflammation, and osteoporosis risk. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 2017;15:59–68. 10.1007/s12018-017-9229-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steptoe A, Hamer M, Chida Y. The effects of acute psychological stress on circulating inflammatory factors in humans: a review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:901–12. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, et al. The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int 2016;27:1281–386. 10.1007/s00198-015-3440-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brennan SL, Pasco JA, Urquhart DM, et al. The association between socioeconomic status and osteoporotic fracture in population-based adults: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 2009;20:1487–97. 10.1007/s00198-008-0822-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brennan SL, Pasco JA, Urquhart DM, et al. The association between urban or rural locality and hip fracture in community-based adults: a systematic review. J of Comm Health 2010;64:656–65. 10.1136/jech.2008.085738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan SL, Wluka AE, Gould H, et al. Social determinants of bone densitometry uptake for osteoporosis risk in patients aged 50yr and older: a systematic review. J Clin Densitom 2012;15:165–75. 10.1016/j.jocd.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. The Lancet 1999;354:1896–900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04149-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.