Abstract

Objectives

Prompt diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) remains a challenge, with presenting symptoms affecting the diagnosis algorithm and, consequently, management and outcomes. This study aimed to identify sex differences in presenting symptoms of ACS.

Design

Data were collected within a prospective cohort study (EPIHeart).

Setting

Patients with confirmed diagnosis of type 1 (primary spontaneous) ACS who were consecutively admitted to the Cardiology Department of two tertiary hospitals in Portugal between August 2013 and December 2014.

Participants

Presenting symptoms of 873 patients (227 women) were obtained through a face-to-face interview. Outcome measures: Typical pain was defined according to the definition of cardiology societies. Clusters of symptoms other than pain were identified by latent class analysis. Logistic regression was used to quantify differences in presentation of ACS symptoms by sex.

Results

Chest pain was reported by 82% of patients, with no differences in frequency or location between sexes. Women were more likely to feel pain with an intensity higher than 8/10 and this association was stronger for patients aged under 65 years (interaction P=0.028). Referred pain was also more likely in women, particularly pain referred to typical and atypical locations simultaneously. The multiple symptoms cluster, which was characterised by a high probability of presenting with all symptoms, was almost fourfold more prevalent in women (3.92, 95% CI 2.21 to 6.98). Presentation with this cluster was associated with a higher 30-day mortality rate adjusted for the GRACE V.2.0 risk score (4.9% vs 0.9% for the two other clusters, P<0.001).

Conclusions

While there are no significant differences in the frequency or location of pain between sexes, women are more likely to feel pain of higher intensity and to present with referred pain and symptoms other than pain. Knowledge of these ACS presentation profiles is important for health policy decisions and clinical practice.

Keywords: sex, acute coronary syndrome, women, diagnosis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Within a prospective cohort study, presenting symptoms of acute coronary syndrome were obtained through a structured questionnaire applied within the first 48 hours after admission.

Consecutive sampling, the detailed clinical information obtained through the questionnaire and adjustment for several confounding variables strengthens our results.

The results of this study are valid for stable patients admitted to the hospital and who were able to answer the questionnaire in the acute phase of the acute coronary syndrome.

Some of the sex differences in presenting symptoms may be influenced by selection bias because of a higher risk of non-inclusion of women due to misdiagnosis or death in the early hours of admission.

Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is still one of the main causes of death worldwide and in Europe.1 2 Coronary heart disease mortality has decreased in the last decades in high-income countries because of primary prevention and improvement in treatment of patients with ACS.2 Attainment of the maximal benefit of treatment of these patients is threatened by delayed diagnosis, partly dependent on clinical suspicion of ACS. The subjective experience of symptoms influences patients’ attitudes in seeking help and professionals’ interpretation of clinical presentations.3 Early recognition of ACS may be challenging because while patients with presumed ACS have contact with healthcare providers,4 many patients do not have an electrocardiogram (ECG) before hospitalisation.5 Therefore, physicians frequently have to make decisions that are only clinically based.

The population of patients with atypical ACS presentation is still not well characterised.6 Women and men generally have the same type of symptoms during an ACS episode, although the proportion presenting with different combinations of symptoms varies.7 This conflicting evidence can be partly explained by the diverse methodology used, with few prospective studies, usually without a specific questionnaire. In prospective studies, small convenience samples were used and confounding was not always adequately addressed.8 9 Therefore, sex-specific research on ACS presentation is a challenge and priority.10

This study aimed to analyse sex differences in presenting symptoms of ACS within a prospective cohort study, taking into account the contribution of age, socioeconomic data, previous history of coronary heart disease, risk factors, comorbidities, type of ACS and coronary anatomy to the presenting symptoms.

Methods

Study design and sample selection

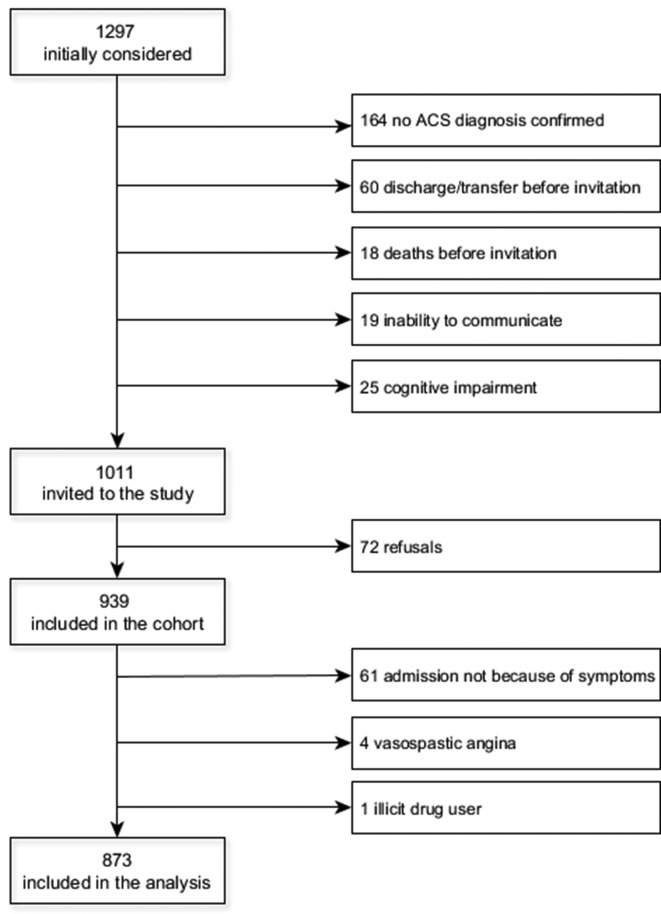

The EPIHeart cohort study was designed to identify inequalities in management and outcomes of patients with ACS. This study included all consecutive patients who were admitted between August 2013 and December 2014 to the Cardiology Department of two tertiary hospitals in two regions in northern Portugal (Hospital de São João, Porto, covering the metropolitan area of Porto in the coast; and Hospital de São Pedro, Vila Real, covering the interior, northeastern region). Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older who lived in the catchment area of these hospitals (districts: Porto, Vila Real, Bragança, and Viseu), with confirmed diagnosis of type 1 (primary spontaneous) ACS. The diagnosis of type 1 ACS and the classification in different subtypes was determined by the treating cardiologist, based on symptoms and signs at presentation, ECG findings and the increase in cardiac enzyme levels (high-sensitivity troponin I or T were used), according to the third universal definition of myocardial infarction.11 The patients were also expected to be hospitalised for at least 48 hours and not institutionalised before the event. Of 1297 patients initially considered, in 164 the diagnosis of type 1 ACS was not confirmed, 60 were excluded due to discharge or transfer before the interview, 18 died before being invited and 44 were unable to answer the questionnaire because of clinical instability, no understanding of Portuguese, hearing problems or cognitive impairment. Seventy-two patients refused to participate. For this analysis, we excluded 61 patients who were not admitted because of a symptom (patients referred by a doctor, after a scheduled appointment or diagnostic exam), 4 with vasospastic angina and 1 illicit drug user. A total of 873 patients were included (figure 1). The study protocol was in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Procedures and data collection

Presenting symptoms were obtained face-to-face using a structured questionnaire applied by trained interviewers, within the first 48 hours after admission, whenever possible. Over the following days, a second interview was conducted to collect data on sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors. Medical records were reviewed to extract data regarding previous medical history, admission information and clinical data during hospitalisation.

Pain, referred pain and symptoms other than pain were measured dichotomously (yes/no). For the location of pain (direct and referred), patients were asked to point out where pain was occurring. To measure the intensity of pain, a 10-point scale (0, no pain; 10, pain of maximal intensity) was used. Symptoms other than pain included dyspnoea at rest, exertional dyspnoea, sweating, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, blurry vision, presyncope, syncope, palpitation, weakness and an open-ended question of ’other' (12 items). Answers to the last item enabled identification of two other relatively frequent symptoms, other digestive symptoms and discomfort. Activity at the onset of the episode was measured dichotomously, including sleeping, rest, and any exertion. A stress trigger was assigned if the patient answered ’yes' for at least one of following events within 24 hours preceding the episode: accident, recent diagnosis of disease, financial problems and news of death/disease of a relative/friend.

Marital status was considered partnered for married patients or living in civil union. Education was recorded as completed years of schooling and classified into four categories: <4 (little formal education), 4 (elementary school), <12 (high school) and 12 or more years (secondary education or more). Occupations were classified into major professional groups, according to the Portuguese Classification of Occupations 2010,12 integrated in the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO/2008).

Definition of variables

Although symptoms of ACS have been widely described, their value for diagnosis of ACS is not unanimously recognised.13–15 After discussion with clinical cardiologists of our team, we opted to use Cardiology Societies’ position papers to define direct and referred pain locations and to select symptoms to evaluate.16 17 Direct pain location was classified as follows: 1) typical for retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic or bilateral thoracic pain (chest pain); 2) atypical for epigastric pain or located in the back, left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw and 3) a mixture when both typical and atypical locations were present. Referred pain location was considered as follows: 1) typical if pain referred to the left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw; 2) atypical if pain referred to retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic, bilateral thoracic, epigastric or back regions and 3) a mixture for referred pain in typical and atypical locations.

Patients rarely present with a single symptom during an episode of ACS, and present with multiple symptoms instead that do not occur in isolation and may cluster.18 There has been increasing interest in symptom cluster analysis in cardiovascular disease because it aids in assessment by enhancing recognition of patients with similar symptom profiles.19 Groups of symptoms other than pain were obtained by latent class analysis.

The small group of non-classified (NC) patients with ACS (patients with left bundle branch block) was grouped with patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (STEMI/NC ACS group). Non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTEACS) included unstable angina and non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction or subacute myocardial infarction.

Considering the possible association between coronary anatomy and clinical presentation, we grouped patients according to coronary angiography into five groups: managed conservatively; non-obstructive coronary artery disease; lesions exclusively in the anterior descending artery; lesions in the right and/or circumflex artery and lesions in the left main coronary artery, three-vessel disease or disease both in the anterior descending artery and the right or circumflex artery.

Data analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are shown as number and percentage. To compare differences between women and men, and by age groups, the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and the t-test, Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Latent class analysis was used to identify distinct groups of individuals from a sample (clusters) who were homogeneous within the group. This was based on the fact that performance of an individual in a set of items is explained by a categorical latent variable with K classes (clusters), commonly called latent classes. The number of latent clusters was defined according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Starting from one single cluster and increasing one cluster at each step, the best solution was identified when an increase in the number of clusters did not lead to a decrease in the AIC.

Patient and system delays, severity indicators, risk stratification using calculated GRACE and CRUSADE risk scores, left ventricular systolic dysfunction and 30-day mortality rate adjusted for the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) V.2.0 risk score,20 were assessed according to the presence of typical (chest) pain and cluster of symptoms other than pain. The 30-day mortality adjusted for the GRACE V.2.0 risk score was estimated based on predicted probabilities derived from logistic regression. Logistic regression was used to identify variables associated with clinical presentation. Variables with P<0.15 for a crude association with the end point were entered in the initial model and a backward strategy was used to exclude the least significant variables, based on Wald tests. We were then able to obtain the most parsimonious model with all the important determinants. Previous data support significant interaction between age and sex with clinical presentation, attenuated with advancing age, mainly in those aged 65 years or older.3 We assessed for effect measure modification by stratifying adjusted analyses based on two age groups (under 65 and 65 years or older). Considering the relevance of analysing sex differences in ACS clinical presentation in younger patients, we also performed the age-stratified multivariate models using 55 years as cut-off age. Sex, age (continuous) and type of ACS were forced to remain in the models.

All analyses were performed using STATA V.11.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and R V.2.12.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Women (n=227, 26.0%) were older (69.1 vs 62.2 years, P<0.001) and more frequently lived in the interior region (52.4% vs 38.7%, P<0.001) than men. Women were more often treated conservatively and had non-obstructive coronary artery disease more frequently than men. In this sample, no difference by sex was observed in the type of ACS, where 56.6% of the patients had a discharge diagnosis of NSTEACS (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, socioeconomic and clinical characteristics in the whole sample and by sex*

| Total (n = 873) |

Women (n = 227) |

Men (n = 646) |

P value | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.0 (13.0) | 69.1 (12.7) | 62.2 (12.7) | <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Partnered | 667 (76.8) | 133 (58.9) | 534 (83.2) | <0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| Little formal education | 172 (19.9) | 95 (42.4) | 77 (12.0) | |

| Elementary school | 337 (39.1) | 73 (32.6) | 264 (41.3) | |

| High school | 213 (24.7) | 32 (14.3) | 181 (28.3) | |

| Secondary education or more | 141 (16.3) | 24 (10.7) | 117 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed/looking after home | 282 (32.6) | 64 (28.3) | 218 (34.1) | |

| Unemployed | 107 (12.4) | 16 (7.1) | 91 (14.2) | |

| Retired | 334 (38.6) | 93 (41.2) | 241 (37.7) | |

| Disabled | 143 (16.5) | 53 (23.5) | 90 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Subjective social class | ||||

| Low | 281 (32.2) | 81 (35.7) | 200 (31.0) | |

| Lower-middle | 281 (32.2) | 58 (25.6) | 223 (34.5) | |

| Higher-middle/high | 60 (6.9) | 16 (7.1) | 44 (6.8) | |

| No response | 251 (28.8) | 72 (31.7) | 179 (27.7) | 0.097 |

| Household income (€) | ||||

| <500 | 204 (23.4) | 77 (33.9) | 127 (19.7) | |

| 501–1000 | 276 (31.6) | 60 (26.4) | 216 (33.4) | |

| 1001–2000 | 146 (16.7) | 22 (9.7) | 124 (19.2) | |

| >2000 | 88 (10.1) | 14 (6.2) | 74 (11.5) | |

| No response | 159 (18.2) | 54 (23.8) | 105 (16.3) | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||

| Metropolitan area of Porto | 504 (57.7) | 108 (47.6) | 396 (61.3) | |

| Northeastern region of Portugal | 369 (42.3) | 119 (52.4) | 250 (38.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||||

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Never | 369 (42.3) | 184 (81.0) | 185 (28.6) | |

| Current | 283 (32.4) | 34 (15.0) | 249 (38.5) | |

| Former | 221 (25.3) | 9 (4.0) | 212 (32.8) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 590 (67.6) | 185 (81.5) | 405 (62.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 281 (32.2) | 88 (38.8) | 193 (29.9) | 0.014 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 535 (61.4) | 144 (63.4) | 391 (60.6) | 0.454 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 26.5 (18.0–44.6) | 26.7 (19.5–37.9) | 26.4 (18.2–39.2) | 0.531 |

| Underweight | 11 (1.4) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (1.5) | |

| Normal weight | 272 (33.4) | 80 (37.0) | 192 (32.1) | |

| Overweight | 366 (44.9) | 79 (36.6) | 287 (47.9) | |

| Obese | 166 (20.4) | 55 (25.5) | 111 (18.5) | 0.020 |

| Family history of CVD | 303 (34.7) | 73 (32.2) | 230 (35.6) | 0.105 |

| Previous medical history | ||||

| Renal failure | 64 (7.3) | 14 (6.1) | 50 (7.7) | 0.434 |

| Myocardial infarction | 156 (17.9) | 34 (15.0) | 122 (18.9) | 0.186 |

| PCI | 100 (12.4) | 18 (8.4) | 82 (13.8) | 0.041 |

| CABG | 34 (4.2) | 5 (2.3) | 29 (4.9) | 0.111 |

| Heart failure | 63 (7.5) | 21 (9.6) | 42 (6.8) | 0.172 |

| Dementia | 7 (0.8) | 4 (1.8) | 3 (0.5) | 0.060 |

| ACS type | ||||

| STEMI/NC ACS | 379 (43.4) | 101 (44.5) | 278 (43.0) | |

| NSTEACS | 494 (56.6) | 126 (55.5) | 368 (57.0) | 0.703 |

| Coronary anatomy | ||||

| Non-obstructive disease | 57 (6.9) | 22 (10.6) | 35 (5.61) | |

| Left anterior descending artery only | 162 (19.5) | 38 (18.3) | 124 (19.9) | |

| Right and/or circumflex artery only | 196 (23.6) | 46 (22.1) | 150 (24.0) | |

| Mixture | 417 (50.1) | 102 (49.0) | 315 (50.5) | |

| Not submitted to coronary angiography | 41 (4.7) | 19 (8.4) | 22 (3.4) | 0.004 |

| Symptom questionnaire application | ||||

| Time from admission (hours), median (IQR) | 42.1 (25.0-68.0) | 45.4 (28.5-72.3) | 40.0 (24.0-67.4) | 0.052 |

*Values are number and percentage unless otherwise indicated.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; IQR, interquartile range; NSTEACS, non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI/NC ACS, ST-elevation myocardial infarction/non-classifiable acute coronary syndrome.

Women more frequently had hypertension (81.5% vs 62.7%, P<0.001) and diabetes (38.8% vs 29.9%, P=0.014), and were more frequently obese (25.5% vs 18.5%, P=0.020) and never smokers compared with men (P<0.001, table 1). Men were submitted to percutaneous coronary intervention more often than women. There were no significant differences in a previous history of renal failure, prior myocardial infarction, prior coronary artery bypass surgery, prior heart failure and dementia by sex (table 1).

Women were more likely to be unpartnered, disabled, less educated and had a lower income compared with men. The median time that elapsed between admission and application of the symptom questionnaire was slightly longer in women than in men (table 1).

Symptom characteristics by sex and age

Because differences in symptoms by sex and age were similar in direction and magnitude in STEMI/NC ACS and NSTEACS (see online supplementary table 1 and 2), both types of ACS were analysed together.

Although pain was present in most patients, men presented with pain more frequently than did women (97.4% vs 94.3%, P=0.028), with a higher sex difference among patients aged 80 or more years (88.0% vs 93.5%). Older patients presented less often pain, but the difference by age group in both sexes was not significant (table 2). No difference was found in the location of pain by sex. Approximately 80% of patients felt chest pain (typical pain). Older women presented less frequently with chest pain and had chest pain and pain in other locations (mixture group) more often than did younger women (P=0.014). Referred pain was observed more frequently in women and in younger patients (only significant for men, P=0.024); again in the older age group, the difference between women and men was notorious (56.8% vs 39.7%, respectively). Atypical and mixture referred pain were more frequent in women than in men (P<0.001), mainly in women aged ≥65 years (P=0.009). Women felt pain with higher intensity than did men (median (IQR): 9 (8–10) vs 8 (6–9), P<0.001), without a difference by age (table 2). Women presented with symptoms other than pain more frequently than did men (82.8% vs 68.9%, P<0.001), with no difference by age group in both sexes (table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical presentation of patients with acute coronary syndrome, by sex and age*

| Women | P value† | Men | P value‡ | P value‡ | |||||||||

| ≤45 | 46–64 | 65–79 | ≥80 | Total | ≤45 | 46–64 | 65–79 | ≥80 | Total | ||||

| Total | 14 (6.2) | 54 (23.8) | 109 (48.0) | 50 (22.0) | 227 (100.0) | 61 (9.4) | 303 (46.9) | 220 (34.1) | 62 (9.6) | 646 (100) | |||

| Pain | 14 (100.0) | 52 (96.3) | 104 (95.4) | 44 (88.0) | 214 (94.3) | 0.229 | 60 (98.4) | 297 (98.0) | 214 (97.3) | 58 (93.5) | 629 (97.4) | 0.228 | 0.028 |

| Pain location§ | |||||||||||||

| Typical | 12 (85.7) | 43 (82.7) | 88 (85.4) | 32 (72.7) | 175 (82.2) | 53 (89.8) | 246 (83.7) | 175 (82.2) | 44 (75.9) | 518 (83.0) | |||

| Atypical | 1 (7.1) | 9 (17.3) | 5 (4.9) | 6 (13.6) | 175 (9.9) | 3 (5.1) | 33 (11.2) | 30 (14.1) | 10 (17.2) | 76 (12.2) | |||

| Mixture | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (9.7) | 6 (13.6) | 17 (8.0) | 0.014 | 3 (5.1) | 15 (5.1) | 8 (3.8) | 4 (6.9) | 30 (4.8) | 0.327 | 0.165 |

| Referred pain | 9 (64.3) | 41 (78.8) | 72 (69.2) | 25 (56.8) | 147 (68.7) | 0.129 | 38 (63.3) | 179 (60.3) | 126 (58.9) | 23 (39.7) | 366 (58.2) | 0.024 | 0.007 |

| Radiation type¶ | |||||||||||||

| Typical | 8 (88.9) | 20 (48.8) | 28 (38.9) | 7 (28.0) | 63 (42.9) | 28 (73.7) | 114 (64.4) | 67 (53.2) | 10 (43.5) | 219 (60.2) | |||

| Atypical | 0 (0.0) | 13 (31.7) | 18 (25.0) | 13 (52.0) | 44 (29.9) | 7 (18.4) | 37 (20.9) | 39 (31.0) | 8 (34.8) | 91 (25.0) | |||

| Mixture | 1 (11.1) | 8 (19.5) | 26 (36.1) | 5 (20.0) | 40 (27.2) | 0.009 | 3 (7.9) | 26 (14.7) | 20 (15.9) | 5 (21.7) | 54 (14.8) | 0.104 | <0.001 |

| Pain intensity** | 9.5 (8-10) | 9 (8-10) | 9 (8-9) | 8 (8-9) | 9 (8-10) | 0.170 | 8 (7-10) | 8 (6-9) | 8 (6-9) | 8 (7-9) | 8 (6-9) | 0.095 | <0.001 |

| Symptom | 11 (78.6) | 45 (83.3) | 91 (83.5) | 41 (82.0) | 188 (82.8) | 0.947 | 43 (70.5) | 209 (69.0) | 151 (68.6) | 42 (67.7) | 445 (68.9) | 0.989 | <0.001 |

| Symptom clusters†† | |||||||||||||

| Cluster 1 | 7 (50.0) | 41 (75.9) | 62 (56.9) | 32 (64.0) | 142 (62.6) | 43 (70.5) | 232 (76.6) | 170 (77.3) | 52 (83.9) | 497 (76.9) | |||

| Cluster 2 | 5 (35.7) | 8 (14.8) | 28 (25.7) | 8 (16.0) | 49 (21.6) | 15 (25.6) | 59 (19.5) | 35 (15.9) | 9 (14.5) | 118 (18.3) | |||

| Cluster 3 | 2 (14.3) | 5 (9.3) | 19 (17.4) | 10 (20.0) | 36 (15.9) | 0.183 | 3 (4.9) | 12 (4.0) | 15 (6.8) | 1 (1.61) | 31 (4.80) | 0.345 | <0.001 |

| Activity | |||||||||||||

| Sleep | 2 (15.4) | 16 (32.0) | 11 (10.4) | 7 (14.9) | 36 (16.7) | 6 (9.8) | 65 (21.7) | 35 (16.1) | 13 (21.3) | 119 (18.6) | |||

| Rest | 5 (38.5) | 18 (36.0) | 50 (47.2) | 29 (61.7) | 102 (47.2) | 34 (55.7) | 124 (41.3) | 105 (48.2) | 33 (54.1) | 296 (46.3) | |||

| Exertion | 6 (46.2) | 16 (32.0) | 45 (42.5) | 11 (23.4) | 78 (36.1) | 0.011 | 21 (34.4) | 111 (37.0) | 78 (35.8) | 15 (24.6) | 225 (35.2) | 0.087 | 0.816 |

| Stress trigger | 2 (14.3) | 6 (11.1) | 11 (10.2) | 3 (6.1) | 22 (9.8) | 0.700 | 11 (18.0) | 23 (7.7) | 15 (6.9) | 6 (9.8) | 55 (8.6) | 0.045 | 0.605 |

*Values are number and percentage unless otherwise indicated.

†P for age differences within each sex.

‡P for differences between sexes.

§Pain location: typical—retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic or bilateral thoracic; atypical—epigastric, back, left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw; mixture—typical and atypical location.

¶Radiation type: typical—left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw; atypical: retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic, bilateral thoracic, epigastric or back regions; mixture—typical and atypical irradiation.

**Median (IQR).

††Symptom clusters: cluster 1 (no symptom cluster)—low endorsement probabilities for all items; cluster 2 (dyspnoea and sweating cluster)—high probability for dyspnoea at rest and sweating; cluster 3 (multiple symptoms cluster)—high probabilities for all items (dyspnoea at rest, exertional dyspnoea, sweating, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, blurry vision, presyncope, syncope, palpitation, weakness, other symptoms, other digestive symptoms and discomfort).

Considering symptoms other than pain, the AIC optimum value supported a preference for a three-cluster solution (AIC 7207.508, 6869.390, 6862.476 and 6870.372 for one, two, three and four clusters, respectively). Cluster 1 had low endorsement probabilities for all items (no symptoms cluster). Cluster 2 had a high probability for dyspnoea at rest and sweating, and a low probability for the remaining items (dyspnoea and sweating cluster). Cluster 3 had high probabilities for all items (multiple symptoms cluster). This three-cluster model made sense conceptually to cardiologists of our team. Clusters counts and probabilities of occurrence of symptoms in established clusters are shown in online supplementary table 3. Differences in proportions of women and men in the three clusters were observed (P<0.001, table 2). Cluster 1 was the most prevalent, in which men presented with the no symptoms cluster more frequently (76.9% vs 62.6%) and the multiple symptoms cluster less frequently (4.8% vs 15.9%) than did women. Higher differences of multiple symptoms cluster proportions between women and men were observed among patients in the older age group. The proportion of dyspnoea and sweating cluster was similar in men and women (table 2).

bmjopen-2017-018798supp003.pdf (182.4KB, pdf)

Approximately 45% of patients were at rest and 35% were under physical effort at the beginning of the episode. Older women were more frequently at rest at the beginning of the episode and younger women were more frequently under effort (p=0.011). Less than 10% of patients identified a stressful event in the previous 24 hours, with no difference by sex, but among men, a younger age was slightly associated with this trigger (P=0.045, table 2).

Multivariate models

Despite the higher probability of women below or above 65 years to present without pain than men, no differences were observed in the adjusted pain frequency and location between men and women. Referred pain was more likely to be experienced by women (<65 years: adjusted OR 2.90, 95% CI 1.47 to 5.72; ≥65 years: 1.60 (95% CI 0.99 to 2.60), interaction P=0.528). Moreover, women below or above 65 years had a higher probability of having pain radiating to typical and atypical locations and of feeling pain with an intensity higher than 8 (table 3). The association between intensity of pain and female sex was stronger for patients below 65 years (interaction P=0.028) (table 3).

Table 3.

Differences between women and men in clinical presentation of acute coronary syndrome, by age group (men are the reference class)

| Symptoms | <65 years | ≥65 years | Interaction P value | Adjusted for | ||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||

| Pain | 0.76 | 0.14 to 4.0 | 0.52 | 0.19 to 1.47 | 0.777 | Age, type of ACS, marital status, dyslipidaemia, CABG |

| Typical (chest) pain (vs atypical or mixture)* | 0.97 | 0.44 to 2.14 | 1.71 | 0.90 to 3.23 | 0.973 | Age, type of ACS, coronary anatomy, region, smoking, dyslipidaemia, previous heart failure |

| Referred pain | 2.90 | 1.47 to 5.72 | 1.60 | 0.99 to 2.60 | 0.528 | Age, type of ACS, coronary anatomy, region, income, social class, previous renal failure |

| Radiation type† | ||||||

| Typical | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | Age, type of ACS, employment status, region | |

| Atypical | 1.49 | 0.70 to 3.20 | 1.38 | 0.72 to 2.66 | 0.415 | |

| Mixture | 1.77 | 0.73 to 4.29 | 2.75 | 1.36 to 5.57 | 0.606 | |

| Pain intensity (higher than 8/10) |

3.81 | 2.04 to 7.13 | 2.03 | 1.22 to 3.37 | 0.028 | Age, type of ACS, coronary anatomy, education, professional group, previous AMI |

| Symptoms | 1.98 | 1.00 to 3.91 | 1.85 | 1.10 to 3.12 | 0.799 | Age, type of ACS, region, previous AMI, previous heart failure |

| Symptom clusters‡ | ||||||

| Cluster 1 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | Age, type of ACS, professional group, region, previous AMI | |

| Cluster 2 | 1.07 | 0.53 to 2.15 | 1.67 | 0.97 to 2.87 | 0.246 | |

| Cluster 3 | 3.14 | 1.15 to 8.62 | 4.23 | 2.03 to 8.81 | 0.501 | |

| Activity group | ||||||

| Sleeping | 1 | Reference | 1 | (Reference) | Age, type of ACS, previous heart failure | |

| Rest | 0.68 | 0.33 to 1.38 | 1.38 | 0.74 to 2.57 | 0.284 | |

| Exertion | 0.77 | 0.37 to 1.59 | 1.70 | 0.89 to 3.25 | 0.408 | |

*Pain location: typical—retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic or bilateral thoracic; atypical—epigastric, back, left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw; mixture—typical and atypical location.

†Radiation type: typical—left arm or shoulder, right arm or shoulder, neck or jaw; atypical: retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic, bilateral thoracic, epigastric or back regions; mixture— typical and atypical irradiation.

‡Symptom clusters: cluster 1 (no symptom cluster)—low endorsement probabilities for all items; cluster 2 (dyspnoea and sweating cluster)—high probability for dyspnoea at rest and sweating; cluster 3 (multiple symptoms cluster)—high probabilities for all items (dyspnoea at rest, exertional dyspnoea, sweating, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, blurry vision, presyncope, syncope, palpitation, weakness, other symptoms, other digestive symptoms and discomfort).

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery.

The presence of at least one symptom other than pain occurred almost two times more often in women than in men. With cluster 1 as the reference, clusters 2 and 3 were positively associated with female sex, with the latter being statistically significant. The multiple symptoms cluster was almost fourfold more likely in women than in men (3.92, 95% CI 2.21 to 6.98 in the whole sample, interaction P=0.501) (table 3).

No difference in the type of patients’ activities at the beginning of the episode by sex was observed (table 3).

Performance of age-stratified multivariate models using the 55 years cut-off revealed similar results to the observed using the 65 years cut-off, with some differences mainly in the strength of association of some clinical presentation variables with sex among the younger age group (see online supplementary table 4). Although still not significant, among patients below 55 years, women were less likely to present with typical chest pain (0.65, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.86). A stronger association between female sex and referred pain, and intensity of pain higher than 8/10, among patients in the younger age groups was observed using the 55 instead of the 65 years cut-off. The remaining results were similar in direction and strength of association (table 3 and online supplementary table 4). The precision of the estimates is lower using the 55 cut-off, due to the small sample of patients below 55 years.

bmjopen-2017-018798supp004.pdf (88.8KB, pdf)

Clinical presentation and outcomes

Patients with a diagnosis of STEMI/NC ACS who presented with atypical or mixture pain took longer to seek medical care (135 vs 85 min, P=0.012) and had longer total ischaemic times (414 vs 328 min, P=0.080) than patients with chest pain (table 4). Among patients with NSTEACS, differences in time delays according to pain location were not significant. Patients with atypical or mixture pain presented more frequently with haemodynamic instability at admission (9.7% vs 4.6%, P=0.014) and had also more often moderate-to-severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (32.9% vs 24.9%, P=0.052) than patients with chest pain. The 30-day mortality adjusted for GRACE V.2.0 was not significantly different between patients with chest pain and those with atypical or mixture pain (table 4).

Table 4.

Patient and system delays, severity indicators, risk stratification and 30-day mortality according to clinical presentation*

| Typical (chest) pain† | Atypical or mixture pain | P value | No symptom cluster‡ | Dyspnoea and sweating cluster | Multiple symptoms cluster | P value | |

| Patient and system delays, median (IQR) | |||||||

| STEMI/NC ACS | |||||||

| Symptom onset—FMC (min) | 85 (45–210) | 135 (65–325) | 0.012 | 90 (46–240) | 90 (50–185) | 83 (45–430) | 0.872 |

| Symptom onset—arterial access (min) | 328 (192–1075) | 414 (246–1335) | 0.080 | 321 (194–1011) | 384 (201–1440) | 533 (323–1428) | 0.111 |

| NSTEACS | |||||||

| Symptom onset—FMC (min) | 130 (60–393) | 139 (60–335) | 0.633 | 135 (60–390) | 150 (60–390) | 113 (45–393) | 0.795 |

| Hospital admission—coronary angiography time (hours) | 30 (18–57) | 29 (20–48) | 0.884 | 30 (18–56) | 35 (18–70) | 28 (20–72) | 0.385 |

| Admission variables | |||||||

| Heart rate, mean (SD), bpm | 77 (18) | 80 (24) | 0.117 | 78 (19) | 77 (19) | 78 (28) | 0.923 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 144 (49) | 139 (30) | 0.212 | 145 (59) | 141 (30) | 136 (33) | 0.364 |

| Haemodynamic instability at admission§ | 32 (4.6) | 14 (9.7) | 0.014 | 41 (6.4) | 7 (4.2) | 9 (13.4) | 0.034 |

| Risk stratification | |||||||

| Calculated GRACE risk score, mean (SD) | 134 (36) | 147 (39) | <0.001 | 137 (37) | 138 (35) | 149 (44) | 0.041 |

| Calculated CRUSADE risk score, median (IQR) | 21 (11–34) | 25 (14–41) | 0.012 | 22 (12–36) | 23 (10–36) | 30 (16–47) | 0.019 |

| Moderate or severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 169 (24.9) | 46 (32.9) | 0.052 | 164 (26.4) | 55 (33.3) | 17 (25.4) | 0.187 |

| 30-Day mortality rate adjusted for the GRACE V.2.0 risk score, mean (SD) | 2.0 (4.0) | 1.3 (1.4) | 0.521 | 0.9 (2.0) | 0.9 (2.0) | 4.9 (5.5) | <0.001 |

*Values are number and percentage unless otherwise indicated. Total may not add to 100% due to missing data.

†Chest pain: retrosternal, precordial, right thoracic or bilateral thoracic.

‡No symptom cluster: low endorsement probabilities for all items; dyspnoea and sweating cluster: high probability for dyspnoea atrest and sweating; multiple symptoms cluster: high probabilities for all items (dyspnoea at rest, exertional dyspnoea, sweating, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, blurry vision, presyncope, syncope, palpitation, weakness, other symptoms, other digestive symptoms and discomfort).

§Killip class III or IV; or shock at admission.

CRUSADE, Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes; FMC, first medical contact; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; NSTEACS, non-ST- elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI/NC ACS, ST- elevation myocardial infarction/non-classifiable acute coronary syndrome.

Among patients with STEMI/NC ACS, the total ischaemic time was longer for patients with the multiple symptoms cluster compared with patients who presented with the two other symptoms clusters (533 vs 321 and 384 min, P=0.111). Patients with the multiple symptom cluster presented more often with haemodynamic instability at admission than patients with the other symptoms clusters (13.4% vs 6.4% and 4.2%, P=0.034). The mean 30-day mortality rate adjusted for the GRACE V.2.0 risk score was significantly higher for patients presenting with the multiple symptom cluster (4.9% vs 0.9% for the two other clusters, P<0.001) (table 4).

Patients with atypical or mixture chest pain and patients with the multiple symptom cluster had higher mean GRACE and median Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes (CRUSADE) risk scores (table 4).

Discussion

In our study, after adjustment, no differences in the frequency and location of pain by sex were observed. Referred pain, pain radiating to typical and atypical locations and pain of higher intensity were more likely to occur among women. Women were also more likely than men to present with symptoms other than pain. Three clusters of symptoms other than pain were identified. Women were more likely to present with the multiple symptoms cluster. Presenting with the multiple symptoms cluster was associated with a higher mean 30-day mortality rate adjusted for the GRACE V.2.0 risk score.

Differences between women and men in perception of symptoms of ACS might be explained by anatomical, physiological, biological and psychosocial differences that influence each other.9 21 We measured several variables of these different domains. Differences in symptom presentation by sex might be the result of differences in response to history-taking,10 differences in neural receptors and pathways involved in pain and subtle differences in the location and type of atherosclerotic lesions.22 23 Our findings of similar ACS symptoms between women and men are consistent with previous studies,7 24 as well as our finding that women are more likely to have atypical presentations.9 We observed that women have a higher likelihood of atypical referred pain and of several concomitant symptoms other than pain, common to other cardiac and non-cardiac diagnoses.

In our study, chest pain was the most frequent symptom in both sexes, consistent with previous studies.25–27 Among those with pain, typical chest pain was observed in 82% of patients, regardless of sex. The remaining patients had pain in less typical locations and were thus prone to misdiagnosis and undertreatment and, consequently, to worse outcomes.28 Considering differences in characteristics of pain by sex, studies suggested that women, in particular older women, were less likely to have the chief complaint of chest pain associated with acute myocardial infarction, while after adjustment, among patients aged 65 years or under, female sex was no longer a significant predictor.29 Studies reported that chest pain did not differ between women and men,9 others that women have pain in the neck and back more often than men,30 31 without distinguishing between direct and referred pain. In our study, referred pain was observed in 61% of patients, was more frequent in women and typical referred pain was only observed in 33%. Notably, a study on diagnostic acuity of ACS symptoms showed that shoulder and arm pain was predictive of the diagnosis of ACS for women only.24 Another study Gender and Sex Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease: From Bench to Beyond Premature Acute Coronary Syndrome (GENESIS PRAXY) on sex differences in ACS symptom presentation in patients aged 55 years or younger showed that being a woman was independently associated with ACS presentation without chest pain.27 Although the association was not significant, and relied on a small sample of patients, our finding that women aged 55 years or younger were less likely to present with typical chest pain is in line with the GENESIS PRAXY study result.27 We were also able to find a stronger association between female sex and presence of referred pain, and of pain with intensity higher than 8 among the younger subgroups of patients (aged below 55 and 65 years). These findings stress the relevance of taking into account age for studying the association between sex and clinical presentation. However, further conclusions on the role of age to this relation are limited by the small number of women below 55 years included in our study. Differences in age distribution, in clinical presentation measuring, in selection and definition of confounder variables limit conclusive comparisons of studies evaluating differences in frequency and location of pain between women and men.

According to previous studies, with regard to other symptoms, a higher proportion of women have less typical symptoms than men.8 31 Women have also reported other symptoms, such as indigestion, palpitations, nausea, numbness in the hands and unusual fatigue, more frequently than men.9 In our cohort, three symptom clusters were identified. Women had the multiple symptoms cluster more frequently than did men, characterised by high probabilities for all symptoms. Age did not change the association between female sex and presentation with symptoms other than pain and with the multiple symptoms cluster. According to Rosenfeld et al, women are more likely to cluster in a similar class, called the heavy symptom burden class.32 With regard to ACS symptom clustering, there are contradictory findings on identified clusters, the proportion of patients per cluster and differences between clusters regarding demographic factors. In our study, clusters 1 and 3 (low and high probabilities for all symptoms, respectively) are in line with observations of other settings.18 33 A recent systematic review of symptom clusters in cardiovascular disease34 identified clusters with the most symptoms and clusters with the lowest number of symptoms. Our dyspnoea and sweating cluster has two common symptoms similar to the Riegel et al26 stress symptoms cluster, which includes shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, indigestion, dread and anxiety.

Methodological differences related to sampling and measuring might explain these different results. Strengths of our study include consecutive sampling, a questionnaire with detailed clinical information was systematically applied and we adjusted for several confounding variables.

The value of symptoms for diagnosis of ACS varies across studies.13 14 35 Overall, the diagnostic performance of chest pain characteristics for diagnosis is limited, with likelihood ratios close to 1.36 Sensitivity for individual symptoms of ACS, using the 13-Item ACS Checklist, ranges from 27% to 67% for women and 14% to 72% for men. Additionally, specificity ranges from 33% to 78% for women and 34% to 78% for men, with different associations between some symptoms and diagnosis of ACS by sex.24 However, physicians still base the likelihood of ACS mainly on symptoms and use the ECG to rule in the diagnosis.37 Evaluation of these patients is mostly unchanged, without implementation of evidence-based assessment tools in clinical practice to improve diagnostic accuracy. Public health messages should take into account the complexity of presenting symptoms of ACS, particularly the significant proportion of women and men with ACS without typical chest pain. Additionally, there is a higher likelihood of atypical referred pain and multiple concomitant symptoms in women. These factors should be accounted for to encourage timely and appropriate care of patients with ACS.

Presenting without chest pain and with the multiple symptoms cluster was associated with several markers of higher ACS severity and longer time delays, particularly significant among patients with STEMI/NC ACS. In our study, presenting with the multiple symptoms cluster, but not with atypical or mixture location of pain, was associated with a higher mean 30-day mortality adjusted for GRACE risk score. These results are consistent with data from the GRACE registry, which showed that patients with symptoms other than pain experienced greater morbidity and higher in-hospital mortality across the spectrum of ACS.28 Other registry showed that the higher in-hospital mortality observed among women and men without chest pain, decreased or even reversed with advanced age.38 Mortality is adjusted for GRACE risk score; however, we cannot conclude that the difference in outcome observed is explained by symptoms other than pain per se. Previous studies showed that the higher in-hospital mortality of patients with ACS who presented without chest pain was mostly due to late hospital arrival, comorbidities and underuse of medications and invasive procedures. 3 6 38 These studies focused mainly on presence of chest pain to define atypical presentation and used medical record reviews to characterise clinical presentation. More studies are needed to further explore the association between symptoms other than pain and outcomes.

Limitations

Participants were interviewed as soon as possible after admission, but this does not obviate the retrospective nature of data collection and the possibility of recall bias. Furthermore, preceding interviews by physicians may have influenced answers to the questionnaire; however, different consequences in women and men are not expected. The results of this study are valid for stable patients, who were admitted to the hospital and were able to answer the questionnaire in the acute phase of ACS. This type of study misses patients who die before reaching the hospital, patients who do not seek medical care, patients who are mistakenly discharged or misdiagnosed and admitted to non-cardiology departments. This sample selection process may contribute to underestimate the true prevalence of ACS atypical presentation in women and men.27 For patients who were eligible but not enrolled, only information on sex, age and type of ACS was available. Patients who died before the interview were older (81.5±11.8 vs 64.6±13.1 years, P<0.001), were more often women (66.7% vs 26.0%, P<0.001) and more frequently had a diagnosis of STEMI (81.3% vs 43.4%, P=0.003) than did participants. Patients who were discharged or transferred to another hospital before the interview had STEMI less often (25.0% vs 43.4%, P=0.005) and patients who were not enrolled because of clinical instability or inability to understand the questionnaire were older. Patients who refused to participate were older (72.7±11.0 vs 64.0±13.0 years, P<0.001), were less often partnered (65.7% vs 76.8%, P=0.036) and had little formal education (43.1% vs 19.7%, P<0.001) compared with participants. Except for deceased patients, no difference in sex proportion was observed between participants and non-participants. We cannot exclude that some of the sex differences were caused by selection bias because of a higher risk of non-inclusion of women due to death in the early hours of admission, or due to a possible higher probability of misdiagnosis in women, particularly those with unstable angina.39 Considering that atypical presentation is associated with a worse prognosis and with a higher probability of misdiagnosis, the proportion of patients with ACS presenting without typical chest pain or that of women with an atypical presentation could be even higher.28

Conclusion

This study shows no significant differences in the frequency and location of pain by sex, but approximately 20% of patients do not present with chest pain, regardless of sex. Women are more likely to report referred pain and multiple symptoms simultaneously. Presentation with the multiple symptoms cluster pain is associated with higher 30-day mortality adjusted for GRACE score. Health education messages should take into account the complexity of presentation of ACS and emphasise the possible non-chest location of pain in both sexes and the higher probability of concomitant symptoms other than pain in women. Further sex-stratified analysis of ACS presentation, also addressing the role of age for the relation between sex and clinical presentation, is required to determine the diagnostic accuracy of symptoms by sex.

bmjopen-2017-018798supp001.pdf (194.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018798supp002.pdf (117.1KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CA and AA had the original idea to develop the EPIHeart cohort study and were responsible for acquiring the study grant. CA raised the hypotheses, participated in data collection and field work, analysed and interpreted the data and drafted the first version of the manuscript. OL analysed and interpreted the data, participated in drafting and revising the first draft of the manuscript. MV and AB participated in data collection, field work and interpretation of the data. FM and AH interpreted data. MS analysed and interpreted the data. MJM and IM were involved in the conception of the study and in field work. AA was the responsible for the conception and development of the study, analysed and interpreted the data, participated in drafting and revising the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in writing the paper, in revising it critically and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by FEDER through the Operational Programme Competitiveness and Internationalization and national funding from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education) (FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-028709), under the project ’Inequalities in coronary heart disease management and outcomes in Portugal' (Ref. FCT PTDC/DTP-EPI/0434/2012) and Unidade de Investigação em Epidemiologia—Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (EPIUnit) (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006862; Ref. UID/DTP/04750/2013).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: all authors had financial support through grants from the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT; Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education) and from Unidade de Investigação em Epidemiologia—Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto. No financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of both hospitals involved: Comissão de Ética para a Saúde do Centro Hospitalar de S. João and Comissão de Ética do Centro Hospitalar de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, reference numbers of the approvals: 82/13 and 1286, respectively.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available by emailing the corresponding author at carla-r-araujo@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Mendis S. Global Status Report on noncommunicable diseases 2014 report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, et al. . Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J 2014;35:2950–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, et al. . Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. JAMA 2012;307:813–22. 10.1001/jama.2012.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doggen CJ, Zwerink M, Droste HM, et al. . Prehospital paths and hospital arrival time of patients with acute coronary syndrome or stroke, a prospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med 2016;16:3 10.1186/s12873-015-0065-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Annemans L, Danchin N, Van de Werf F, et al. . Prehospital and in-hospital use of healthcare resources in patients surviving acute coronary syndromes: an analysis of the EPICOR registry. Open Heart 2016;3:e000347 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manfrini O, Ricci B, Cenko E, et al. . Association between comorbidities and absence of chest pain in acute coronary syndrome with in-hospital outcome. Int J Cardiol 2016;217 (Suppl):S37–S43. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeVon HA, Zerwic JJ. Symptoms of acute coronary syndromes: are there gender differences? A review of the literature. Heart Lung 2002;31:235–45. 10.1067/mhl.2002.126105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeVon HA, Zerwic JJ. The symptoms of unstable angina: do women and men differ? Nurs Res 2003;52:108–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVon HA, Ryan CJ, Ochs AL, et al. . Symptoms across the continuum of acute coronary syndromes: differences between women and men. Am J Crit Care 2008;17:14–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safdar B, Nagurney JT, Anise A, et al. . Gender-specific research for emergency diagnosis and management of ischemic heart disease: proceedings from the 2014 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference Cardiovascular Research Workgroup. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1350–60. 10.1111/acem.12527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2551–67. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics. Statistics Portugal. Portuguese classification of occupations. 2011. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_publicacoes&PUBLICACOESpub_boui=107961853&PUBLICACOESmodo=2 (accessed 15 Nov 2016).

- 13.Swap CJ, Nagurney JT. Value and limitations of chest pain history in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2005;294:2623–9. 10.1001/jama.294.20.2623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eslick GD. Usefulness of chest pain character and location as diagnostic indicators of an acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:1228–31. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canto AJ, Kiefe CI, Goldberg RJ, et al. . Differences in symptom presentation and hospital mortality according to type of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2012;163:572–9. 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. . ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-Segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2015;2016:267–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. . AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;2014:e344–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan CJ, DeVon HA, Horne R, et al. . Symptom clusters in acute myocardial infarction: a secondary data analysis. Nurs Res 2007;56:72–81. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000263968.01254.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miaskowski C, Dodd M, Lee K. Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004:17–21. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiele F, Gale CP, Bonnefoy E, et al. . Quality indicators for acute myocardial infarction: A position paper of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2017;6:34–59. 10.1177/2048872616643053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Legato MJ. Gender and the heart: sex-specific differences in normal anatomy and physiology. J Gend Specif Med 2000;3:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foreman RD. Mechanisms of cardiac pain. Annu Rev Physiol 1999;61:143–67. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arslanian-Engoren C, Engoren M. Physiological and anatomical bases for sex differences in pain and nausea as presenting symptoms of acute coronary syndromes. Heart Lung 2010;39:386–93. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devon HA, Rosenfeld A, Steffen AD, et al. . Sensitivity specificity, and sex differences in symptoms reported on the 13-item acute coronary syndrome checklist. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000586 10.1161/JAHA.113.000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arslanian-Engoren C, Patel A, Fang J, et al. . Symptoms of men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:1177–81. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riegel B, Hanlon AL, McKinley S, et al. . Differences in mortality in acute coronary syndrome symptom clusters. Am Heart J 2010;159:392–8. 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, et al. . Sex differences in acute coronary syndrome symptom presentation in young patients. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1863–71. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, et al. . Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest 2004;126:461–9. 10.1378/chest.126.2.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner KA, Vaccarino V, Arnold AL, et al. . Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study). Am J Cardiol 2004;93:606–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everts B, Karlson BW, Währborg P, et al. . Localization of pain in suspected acute myocardial infarction in relation to final diagnosis, age and sex, and site and type of infarction. Heart Lung 1996;25:430–7. 10.1016/S0147-9563(96)80043-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg R, Goff D, Cooper L, et al. . Age and sex differences in presentation of symptoms among patients with acute coronary disease: the REACT Trial: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment. Coron Artery Dis 2000;11:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld AG, Knight EP, Steffen A, et al. . Symptom clusters in patients presenting to the emergency department with possible acute coronary syndrome differ by sex, age, and discharge diagnosis. Heart Lung 2015;44:368–75. 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindgren TG, Fukuoka Y, Rankin SH, et al. . Cluster analysis of elderly cardiac patients' prehospital symptomatology. Nurs Res 2008;57:14–23. 10.4088/JCP.v69n0414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeVon HA, Vuckovic K, Ryan CJ, et al. . Systematic review of symptom clusters in cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017;16:6–17. 10.1177/1474515116642594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruyninckx R, Aertgeerts B, Bruyninckx P, et al. . Signs and symptoms in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome: a diagnostic meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:1–8. 10.3399/bjgp08X277014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubini Gimenez M, Reiter M, Twerenbold R, et al. . Sex-specific chest pain characteristics in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:241–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamali A, Söderholm M, Ekelund U. What decides the suspicion of acute coronary syndrome in acute chest pain patients? BMC Emerg Med 2014;14:9 10.1186/1471-227X-14-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al. . Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain. JAMA 2000;283:3223–9. 10.1001/jama.283.24.3223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, et al. . Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1163–70. 10.1056/NEJM200004203421603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018798supp003.pdf (182.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018798supp004.pdf (88.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018798supp001.pdf (194.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018798supp002.pdf (117.1KB, pdf)