The United States is in the middle of a historically unprecedented opioid epidemic. Today, more people die of drug overdoses than any other form of accidental death, and opioid overdose rates surpass historic peak death rates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), gun violence, and motor vehicle accidents.1,2 Opioid addiction rates are at all-time high. In 2014, 4.3 million people abused prescription opioids, 1.9 million people had an opioid use disorder related to prescription pain relievers, and another 586,000 people had an opioid use disorder related to heroin.3 This epidemic is attributable to a confluence of circumstances, primarily overprescribing by physicians combined with an influx of potent heroin from Mexico. The epidemic has received additional fuel and urgency from the rise of extremely potent synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, carfentanil, and others. These synthetic drugs are often consumed unknowingly, mixed in illicit street heroin or compounded in fake versions of prescription opioids. As with other chronic medical illnesses, opioid addiction, once developed, has no cure and requires ongoing monitoring and treatment. Therapy alone and abstinence-based models rather than medication-assisted treatment have dominated opioid treatment until now. Despite detoxification combined with psychosocial treatment, relapse rates remain at 90% or higher.4 These high relapse rates have been confirmed in populations that abuse heroin as well as prescription opioids.5,6 Renewed use after abstinence is associated with a high overdose risk, likely the result of the loss of previous tolerance and misjudgment of safe amounts.

HISTORIC CONTEXT

To understand the legal and medical framework for treating this epidemic, it is necessary to examine a smaller, yet not insignificant, opioid epidemic. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, laudanum treatment for pain and opium dens associated with Chinese immigrants led to alarm and racist hysteria.7 Physicians attempted to detoxify and safely maintain these patients with opioid medications. The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 restricted the use of opioids to pain treatment and outlawed their use for addiction management.8 The act framed opioid dependence and substance abuse in general as a criminal or moral rather than as a medical issue. Thirty thousand physicians, some engaged in unethical practice, some not, were prosecuted under this act.7 Opioid addiction remained a difficult-to-treat problem, with very low recovery rates.

The work of Dole and Nyswander at Rockefeller University in the 1960s showed that the treatment of opioid addiction with methadone, a high-affinity, long-acting opioid, led to reduced criminal behavior and improved function.9,10 The success of their research paved the way for methadone to become the first legally allowed opioid treatment for addiction since 1914. The Controlled Substances Act of 197011 and the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act of 197412 allowed dispensation of specific opioids from federally waived clinics. This legal dispensation saved lives and improved public health outcomes by helping to limit the spread of hepatitis C and HIV.13,14 However, the utility of methadone was limited by strict regulation and the need for patients to attend special clinics—typically on a daily basis—that was undesirable for many potential patients and impossible for those who lacked access.

Buprenorphine, the opioid in Suboxone, was developed in the 1970s as a safer opioid than morphine or heroin for the treatment of pain. Studies suggested that buprenorphine could be an attractive alternative to methadone, as it could require fewer regulations because of its inherent abuse deterrence properties as a partial opioid agonist-antagonist.15 The drug's manufacturer and the addiction treatment community lobbied for an exception to the Narcotic Addict Treatment Act to allow individual providers, rather than federally designated clinics, to prescribe buprenorphine. The Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 authorized physicians via a new individual waiver to prescribe specific opioids for the treatment of opioid use disorder.16 Buprenorphine is currently the only opioid authorized under this waiver.

BUPRENORPHINE PHARMACOLOGY/MECHANISM

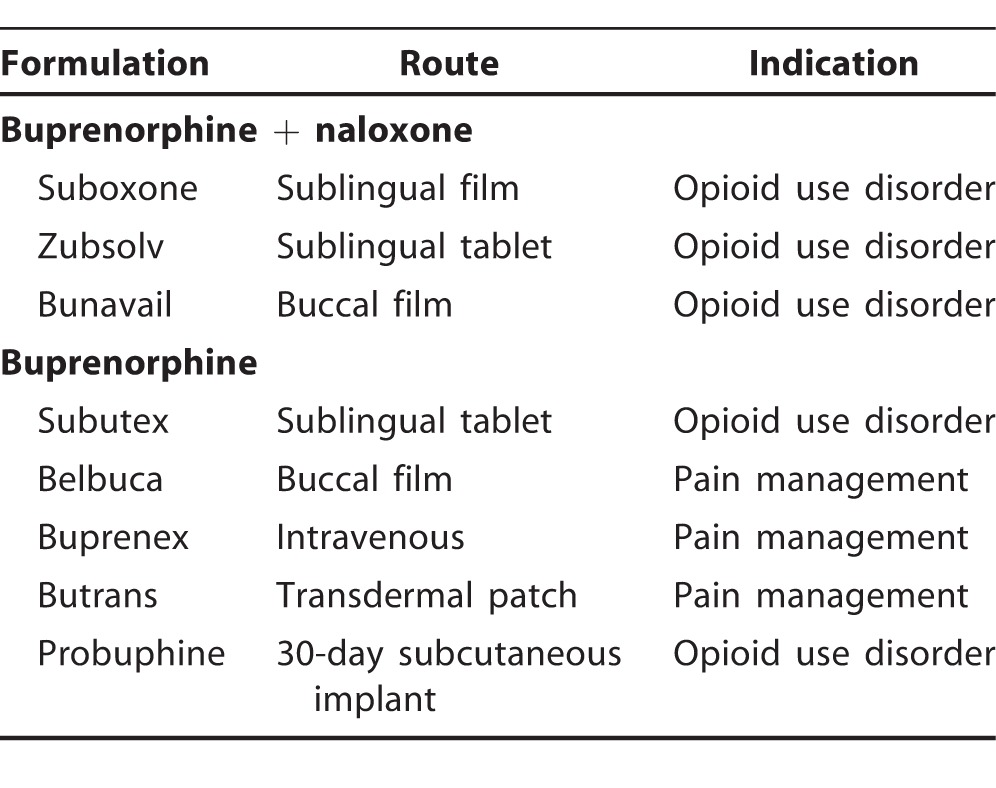

Buprenorphine is a long-acting, high-affinity partial agonist at the mu-opioid receptor. As a long-acting agonist, buprenorphine prevents withdrawal and craving and stabilizes opioid receptors. As a high-affinity agonist, buprenorphine blocks other opioids from binding, preventing abuse of other opioids. As a partial agonist, it has a smaller effect with a ceiling, a low overdose risk, and no intoxication in the opioid dependent. Buprenorphine is available in many formulations (Table 1). The most common formulation is buprenorphine and naloxone (Suboxone) in a 4:1 ratio.17 As an opioid antagonist with high first-pass hepatic metabolism, naloxone has no effect on sublingual use of buprenorphine but blocks intravenous or intranasal abuse of buprenorphine. In contrast, naltrexone is another opioid antagonist with greater oral bioavailability that blocks all opioids regardless of delivery method and is also US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for treatment of opioid use disorder. Buprenorphine without naloxone is used for pain management and can be prescribed for opioid use disorder in sublingual film or tablet form. Except in the case of severe hepatic impairment or pregnancy, prescription of isolated buprenorphine is discouraged given the potential for intravenous abuse.

Table 1.

Formulations and Indications of Buprenorphine With and Without Naloxone

BUPRENORPHINE DOSING

The most common dosing of buprenorphine is 8-24 mg daily. Patients need to be in sufficient opioid withdrawal for induction, typically 12-24 hours after last use. The starting dose is 4-8 mg on the first day with gradual titration. The requirement to be in withdrawal and the need for gradual titration may limit the use of buprenorphine in patients with acute pain in hospital settings. Buprenorphine is a Schedule III medication requiring special waiver (X number). Physicians can obtain waivers by taking an 8-hour course that is available online and in person.18 Advanced practice professionals can apply for waivers as well but need a supervising physician with an X number. The initial limit is 30 patients, but this limit can be increased to 100 and then 275 patients after year-long periods. The physician must be able to offer concurrent counseling or to refer patients to counseling. In the hospital, a physician does not need to have an X number to continue buprenorphine for opioid-dependent patients with acute medical conditions as is the case with methadone.

EVIDENCE FOR USE OF BUPRENORPHINE

As elaborated below, current evidence shows buprenorphine is superior to methadone for tolerability but equivalent for treatment retention and other outcomes. The data also indicate that buprenorphine is equal or superior to antagonist-based treatment (depot intramuscular and oral naltrexone). US Department of Veterans Affairs guidelines currently recommend either buprenorphine or methadone vs depot intramuscular naltrexone, oral naltrexone, or abstinence-based treatment.19

Several placebo-controlled studies document the general efficacy of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Patients in a Swedish treatment program randomized to buprenorphine had 1-year retention of 75% and negative urine drug tests in 75% of patients compared to 0% of patients randomized to placebo.20 One major randomized placebo-controlled trial was terminated early because of the clear superiority of buprenorphine to placebo, with 4 times the rate of negative urine drug tests and significantly less craving in patients on buprenorphine.21 The follow-up open-label study showed continued benefit and no increase in adverse events compared to placebo.21 In another study of 110 patients initiated on buprenorphine, those who remained on buprenorphine after 18 months were more likely to be sober, employed, and involved in 12-step groups.22

Buprenorphine significantly lowers the risk of mortality and adverse outcomes. In a metaanalysis, both methadone and buprenorphine maintenance were found to be superior to detoxification alone in terms of treatment retention, adverse outcomes, and relapse rates.6 Studies have also shown a reduction in all-cause and overdose mortality and significantly improved quality-of-life ratings with maintenance buprenorphine.23,24 Patients on buprenorphine had reduced rates of HIV and hepatitis C transmission compared to abstinence-based therapy or detoxification alone.13,14 Maintenance buprenorphine is also associated with better hepatitis C treatment outcomes.25

Suboxone has been shown to have similar efficacy to methadone when treatment conditions are similar and when patients take higher doses of Suboxone. One early study suggested that methadone was associated with better treatment retention and more negative urine drug tests than buprenorphine.26 These findings were hypothesized to be attributable to increased dependence on the medication because of the full agonist activity and the support provided by the daily visits required for methadone treatment.27,28 However, this study and other early studies typically underdosed buprenorphine, prescribing only 8 mg to many participants. When the subgroups on lower doses were excluded in later analyses, the outcomes between buprenorphine and methadone were the same.26,29 This equipoise argues for buprenorphine instead of methadone, given the better safety profile of the former. As a full agonist, methadone has more than 4 times the risk of overdose than buprenorphine.30 Buprenorphine has rarely been linked to overdoses outside of concurrent alcohol or other sedative abuse and lacks the QTc prolongation and drug-drug interactions of methadone.31

Oral naltrexone has been established as inferior to the extended-release depot form of naltrexone (Vivitrol) and to buprenorphine. Rates of relapse for oral naltrexone and placebo at 6 months were similar, and both were 3 times higher than the relapse rate for patients on buprenorphine maintenance.32 Several recent studies indicate that buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone are equally efficacious. Two naturalistic studies showed better treatment retention for buprenorphine products compared to extended-release naltrexone.33,34 An outpatient-based randomized open-label study in Norway showed similar treatment retention and rates of negative urine drug screens between extended-release naltrexone and buprenorphine-naloxone, with significantly fewer days of heroin and illicit opioid use.35 This study was limited in that it only followed patients for 12 weeks. A 2017 randomized controlled study of buprenorphine and extended-release naltrexone conducted for 6 months found both medications to be equally efficacious in the per-protocol analysis.36 However, the intention-to-treat sample showed buprenorphine to be superior to extended-release naltrexone because of the relative difficulty of induction on antagonist-based therapy, which carries a higher probability of eliciting withdrawal symptoms even weeks after the last illicit opioid use. Of the 283 patients randomized to extended-release naltrexone, 79 failed induction and ultimately relapsed.36 Buprenorphine may also be a safer option than antagonist-based treatment. A longitudinal study showed 8 times the risk of overdose after patients left naltrexone treatment compared to agonist treatment.37

According to 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines, buprenorphine is the treatment of choice for opioid-dependent women in pregnancy and is safer than methadone or medical withdrawal.38 This recommendation for buprenorphine rather than abstinence-based or antagonist treatment is based on the high risk associated with opioid withdrawal and detoxification in pregnancy. Studies have shown higher birth weight, larger head circumference, less preterm birth, and less neonatal withdrawal symptoms in the babies of patients on buprenorphine vs methadone.39 Of note, naltrexone is contraindicated in pregnancy, as it typically requires or precipitates opioid withdrawal. To treat opioid use disorder in pregnancy, providers historically were recommended to prescribe buprenorphine without naloxone (Subutex) given the theoretical risk of naloxone crossing the placenta.38 However, because of the extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism of naloxone, many researchers conclude that Suboxone is as safe as or safer than Subutex in pregnancy, except in cases of severe hepatic impairment. Recent studies show little placental transfer of naloxone and equivalent safety between buprenorphine/naloxone and buprenorphine alone.40-43

In line with the move toward maintenance and chronic opioid treatment rather than detoxification and abstinence, studies suggest that treatment duration should be years rather than weeks to months for most patients. The FDA recently adjusted its labeling to state that some patients will benefit from indefinite buprenorphine treatment.44 Tapers should be individualized because of the potential for worsened outcomes with forced tapers. The risk of relapse is equally high after 2-week and 12-week stabilization periods before taper, with no further benefit from counseling posttaper.4 Young adults randomized to 12 weeks of maintenance buprenorphine before taper had fewer positive urine drug tests, adverse outcomes, and dropouts than those randomized to detoxification alone. No significant difference in relapse rates persisted at follow-up, suggesting that the benefit to maintenance, at least for the short term, only lasts as long as the maintenance treatment.45

Waiver guidelines dictate that physicians have the ability to refer patients to adjunctive psychosocial therapy. The benefit of psychosocial treatment in addition to buprenorphine maintenance, however, is uncertain, with only 4 of 8 studies showing benefit.46 Certain subgroups, such as heroin users or those with severe disease, may benefit more.47 Therapy-based outcomes are difficult to measure, particularly in this population because of the chronic nature of addiction, and therapy and support needs may wax and wane over time. Further, studies often exclude patients with other substance use disorders, selecting more stable patients than typically present in the general population. In my experience as an addiction psychiatrist, patients commonly need more support in the initial stages of treatment, such as that provided in intensive outpatient programs, to maintain engagement and address risk factors.

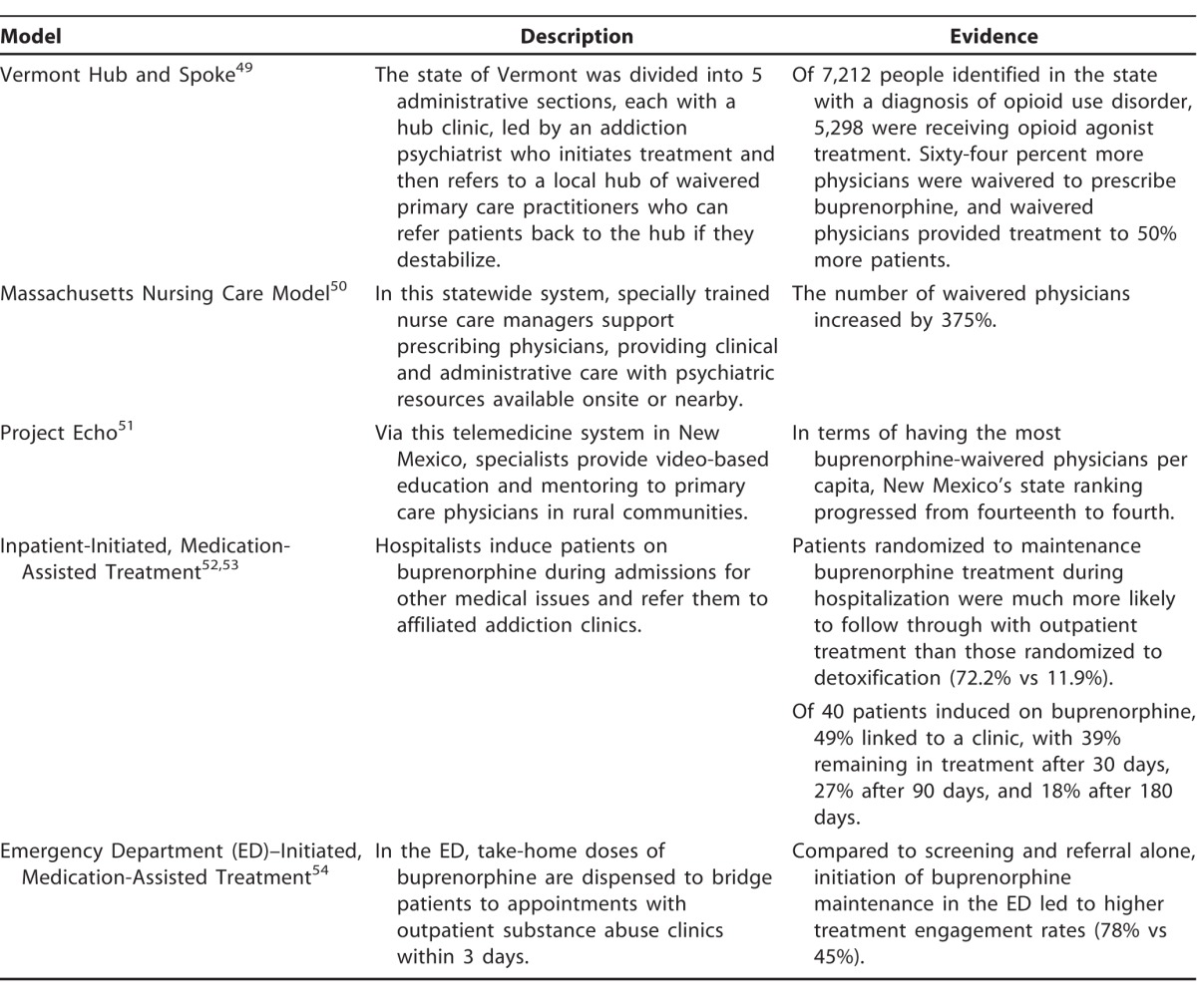

SYSTEM-BASED TREATMENT WITH BUPRENORPHINE

The multiple models for buprenorphine treatment range from minimal support to extensive scaffolded systems. Most commonly, buprenorphine is prescribed by solo practitioners (41.6% psychiatrists, 36.7% primary care physicians) in private practice or small clinic settings who leave the responsibility for psychotherapy largely up to the patient.48 This practice allows for greater access but also runs the risk of inadequate treatment and diversion. Several system-based approaches have been developed with numerous levels of expertise, providers, and support (Table 2).49-54 The benefits of system-based approaches include expanded and rapid access to treatment, more support for prescribers, and the ability to adjust levels of care based on the patient's stability. Ideally, a healthcare system would incorporate elements of several models with routes to treatment initiation in emergency rooms, inpatient medical floors, and primary care and psychiatry offices, in addition to higher levels of psychiatric and addiction care in inpatient and intensive outpatient substance abuse programs.

Table 2.

System-Based Models of Buprenorphine Maintenance Treatment

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT BUPRENORPHINE

Despite substantial evidence for its efficacy and well-developed models of care, buprenorphine remains underutilized. The need for further prescribers is particularly evident in the rural United States and the South.55 As of 2015, the majority of US counties (53.4%), most of them rural, were without a buprenorphine prescriber.48 Louisiana has only 209 providers statewide, with the vast majority concentrated in the New Orleans area.56 Most waivered physicians treat far fewer patients than the 275 potential maximum. Studies suggest that lack of experience and education in the use of buprenorphine is a major reason for its underutilization.57 As an addiction psychiatrist, I have encountered several misconceptions among colleagues and patients who are unfamiliar with buprenorphine that have led to resistance to utilizing it. I discuss 5 of these misconceptions below.

Misconception 1: Suboxone just substitutes one drug for another

If used as directed, buprenorphine-naloxone is a medication, not a substance. It is a stable, safe, long-acting medication with a ceiling effect. It is prescribed for the specific effect of improving patients' physical and mental health and preventing HIV, hepatitis C, other infectious diseases, and death. Thus, it has a clear indication, unlike substances of abuse. Suboxone would likely be more widely accepted as a medication if analogous treatments were available for other addictions. However, no partial-agonist treatment or similarly effective medication is available for alcohol or cocaine use disorders.58

Misconception 2: Suboxone is a “failure of willpower” or “giving up.”

Addiction is a medical disease, not a moral failure. Treatment with a partial agonist allows stabilization of opioid receptors so that patients are able to make changes in lifestyle, behaviors, and psychiatric condition to allow ultimate recovery rather than cycles of relapses. The mortality associated with any relapse on opioids is too high and too final.

Misconception 3: Suboxone is incompatible with 12-step groups like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous

The 12-step groups distinguish between taking medications as prescribed and substance use. Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous were previously hostile to antidepressants and disulfiram (Antabuse), stating that patients on those medications were not really sober, but the organizations have changed their stance. Numerous substance abuse treatment programs combine Suboxone use with 12-step facilitation. The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, possibly the most respected substance abuse treatment institution, has been pioneering integration of partial-agonist therapy with 12-step groups.59 However, real stigma to partial-agonist therapy exists and exerts undue pressure on 12-step participants to prematurely discontinue a lifesaving medication.60

Misconception 4: Patients can get “high” or “loaded” on Suboxone

Intoxication from Suboxone does not occur if a patient is opioid dependent. Intoxication occurs only in patients who combine Suboxone with other substances, do not take it as directed, or use it to medicate withdrawal between episodes of full-agonist opioid abuse. This misuse can be addressed with increased monitoring, urine drug testing, and film/pill counts. Patients are safe to drive while on maintenance doses, and cognitive function in patients on buprenorphine maintenance is likely improved compared to other opioid users.31

Misconception 5: Patients will just sell Suboxone

Physicians can monitor for diversion of Suboxone by instituting film/pill checks and checking urine buprenorphine levels. Furthermore, diversion of medications is not unique to opioids or buprenorphine. The rates of diversion are similar between buprenorphine and antibiotics, both approximately 20%.61 Also the vast majority of diverted buprenorphine is used to self-treat addiction; 64% of opioid users in one study reported using illicit buprenorphine because they were unable to afford or to access treatment.62

CONCLUSION

Buprenorphine-naloxone remains an underutilized treatment for opioid use disorder despite its efficacy, safety, and relative ease of use. To fully address the vast opioid epidemic, more physicians other than addiction subspecialists should be enlisted to diagnose and treat opioid use disorder. With familiarization, training, and formation of support networks, buprenorphine could become a vital part of the community practice and health system response to the opioid epidemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author has no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Health Statistics. Accidents or unintentional injuries. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/accidental-injury.htm. Updated March 17, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 2. Katz J. Drug deaths in America are rising faster than ever. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/06/05/upshot/opioid-epidemic-drug-overdose-deaths-are-rising- faster-than-ever.html. Published June 5, 2017. Accessed October 30, 2017.

- 3. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf. Published September 2015. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 4. Weiss RD., Potter JS., Fiellin DA., et al. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011. December; 68 12: 1238- 1246. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mattick RP., Breen C., Kimber J., Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009. July 8; 3: CD002209 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nielsen S., Larance B., Degenhardt L., Gowing L., Kehler C., Lintzeris N. Opioid agonist treatment for pharmaceutical opioid dependent people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. May 9; 5: CD011117 10.1002/14651858.CD011117.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hamid A. Drugs in America: Sociology, Economics, and Politics. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, Inc.; 1998: 86. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. The Harrison Narcotic Act (1914). http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/library/studies/cu/cu8.html. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 9. Dole VP., Nyswander M. A medical treatment for diacetylmorphine (heroin) addiction. A clinical trial with methadone hydrochloride. JAMA. 1965. August 23; 193: 646- 650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dole VP. Methadone maintenance treatment for 25,000 heroin addicts. JAMA. 1971. February 15; 215 7: 1131- 1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pub L No. 91-513, 84 Stat 1236. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/STATUTE-84/pdf/STATUTE-84-Pg1236.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 12. Pub L No. 93-281, 88 Stat 124. http://www.naabt.org/documents/Narcotic-Addict-Act-1974-public-law-93-281.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 13. Gowing L., Farrell MF., Bornemann R., Sullivan LE., Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011. August 10; 8: CD004145 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsui JI., Evans JL., Lum PJ., Hahn JA., Page K. Association of opioid agonist therapy with lower incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. December; 174 12: 1974- 1981. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jasinski DR., Pevnick JS., Griffith JD. Human pharmacology and abuse potential of the analgesic buprenorphine: a potential agent for treating narcotic addiction. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978. April; 35 4: 501- 516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pub L No. 106-301, 114 Stat 1104. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-106publ310/pdf/PLAW-106publ310.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

- 17. Mendelson J., Jones RT. Clinical and pharmacological evaluation of buprenorphine and naloxone combinations: why the 4:1 ratio for treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003. May 21; 70 2 Suppl: S29- S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Buprenorphine training for physicians. http://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/training-resources/buprenorphine-physician-training. Updated July 7, 2016. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 19. US Department of Veterans Affairs; The Management of Substance Use Disorders Work Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADoDSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf. Published December 2015. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 20. Kakko J., Svanborg KD., Kreek MJ., Heilig M. 1-year retention and social function after buprenorphine-assisted relapse prevention treatment for heroin dependence in Sweden: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003. February 22; 361 9358: 662- 668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fudala PJ., Bridge TP., Herbert S., et al. Buprenorphine/Naloxone Collaborative Study Group. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003. September 4; 349 10: 949- 958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parran TV., Adelman CA., Merkin B., et al. Long-term outcomes of office-based buprenorphine/naloxone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010. January 1; 106 1: 56- 60. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sordo L., Barrio G., Bravo MJ., et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017. April 26; 357: j1550 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitchell SG., Gryczynski J., Schwartz RP., et al. Changes in quality of life following buprenorphine treatment: relationship with treatment retention and illicit opioid use. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015. Apr-Jun; 47 2: 149- 157. 10.1080/02791072.2015.1014948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norton BL., Beitin A., Glenn M., DeLuca J., Litwin AH., Cunningham CO. Retention in buprenorphine treatment is associated with improved HCV care outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017. April; 75: 38- 42. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mattick RP., Kimber J., Breen C., Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. April 16; 2: CD002207 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hser YI., Saxon AJ., Huang D., et al. Treatment retention among patients randomized to buprenorphine/naloxone compared to methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2014. January; 109 1: 79- 87. 10.1111/add.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hser YI., Evans E., Huang D., et al. Long-term outcomes after randomization to buprenorphine/naloxone versus methadone in a multi-site trial. Addiction. 2016. April; 111 4: 695- 705. 10.1111/add.13238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas CP., Fullerton CA., Kim M., et al. Medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014. February 1; 65 2: 158- 170. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bell JR., Butler B., Lawrance A., Batey R., Salmelainen P. Comparing overdose mortality associated with methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009. September 1; 104 1-2: 73- 77. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Soyka M. New developments in the management of opioid dependence: focus on sublingual buprenorphine-naloxone. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2015. January 6; 6: 1- 14. 10.2147/SAR.S45585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schottenfeld RS., Chawarski MC., Mazlan M. Maintenance treatment with buprenorphine and naltrexone for heroin dependence in Malaysia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008. June 28; 371 9631: 2192- 2200. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60954-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morgan JR., Schackman BR., Leff JA., Linas BP., Walley AY. Injectable naltrexone, oral naltrexone, and buprenorphine utilization and discontinuation among individuals treated for opioid use disorder in a United States commercially insured population. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018. February; 85: 90- 96. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Crits-Christoph P., Markell HM., Gibbons MB., et al. A naturalistic evaluation of extended-release naltrexone in clinical practice in Missouri. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016. November; 70: 50- 57. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanum L., Solli KK., Latif ZE., et al. Effectiveness of injectable extended-release naltrexone vs daily buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical noninferiority trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017. December 1; 74 12: 1197- 1205. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee JD., Nunes EV., Novo P., et al. Comparative effectiveness of extended-release naltrexone versus buprenorphine-naloxone for opioid relapse prevention (X:BOT): a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017. November 14 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32812-X [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Digiusto E., Shakeshaft A., Ritter A., O'Brien S., Mattick RP. NEPOD Research Group. Serious adverse events in the Australian National Evaluation of Pharmacotherapies for Opioid Dependence (NEPOD). Addiction. 2004. April; 99 4: 450- 460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 711. Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Opioid-Use-and-Opioid-Use-Disorder-in-Pregnancy. Published August 2017. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 39. Zedler BK., Mann AL., Kim MM., et al. Buprenorphine compared with methadone to treat pregnant women with opioid use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety in the mother, fetus and child. Addiction. 2016. December; 111 12: 2115- 2128. 10.1111/add.13462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wiegand SL., Swortwood MJ., Huestis MA., Thorp J., Jones HE., Vora NL. Naloxone and metabolites quantification in cord blood of prenatally exposed newborns and correlations with maternal concentrations. AJP Rep. 2016. October; 6 4: e385- e390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Debelak K., Morrone WR., O'Grady KE., Jones HE. Buprenorphine + naloxone in the treatment of opioid dependence during pregnancy-initial patient care and outcome data. Am J Addict. 2013. May-Jun; 22 3: 252- 254. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wiegand SL., Stringer EM., Stuebe AM., Jones H., Seashore C., Thorp J. Buprenorphine and naloxone compared with methadone treatment in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015. February; 125 2: 363- 368. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jumah NA., Edwards C., Balfour-Boehm J., et al. Observational study of the safety of buprenorphine+naloxone in pregnancy in a rural and remote population. BMJ Open. 2016. October 31; 6 10: e011774 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA urges caution about withholding opioid addiction medications from patients taking benzodiazepines or CNS depressants: careful medication management can reduce risks. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm575307.htm. Published September 20, 2017. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 45. Woody GE., Poole SA., Subramaniam G., et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008. November 5; 300 17: 2003- 2011. 10.1001/jama.2008.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carroll KM., Weiss RD. The role of behavioral interventions in buprenorphine maintenance treatment: a review. Am J Psychiatry. 2017. August 1; 174 8: 738- 747. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Weiss RD., Griffin ML., Potter JS., et al. Who benefits from additional drug counseling among prescription opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine-naloxone and standard medical management? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014. July 1; 140: 118- 122. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosenblatt RA., Andrilla CH., Catlin M., Larson EH. Geographic and specialty distribution of US physicians trained to treat opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015. Jan-Feb; 13 1: 23- 26. 10.1370/afm.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brooklyn JR., Sigmon SC. Vermont hub-and-spoke model of care for opioid use disorder: development, implementation, and impact. J Addict Med. 2017. Jul-Aug; 11 4: 286- 292. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. LaBelle CT., Han SC., Bergeron A., Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016. January; 60: 6- 13. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Komaromy M., Duhigg D., Metcalf A., et al. Project ECHO (extension for community healthcare outcomes): a new model for educating primary care providers about treatment of substance use disorders. Subst Abus. 2016; 37 1: 20- 24. 10.1080/08897077.2015.1129388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liebschutz JM., Crooks D., Herman D., et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014. August; 174 8: 1369- 1376. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trowbridge P., Weinstein ZM., Kerensky T., et al. Addiction consultation services - linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017. August; 79: 1- 5. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. D'Onofrio G., O'Connor PG., Pantalon MV., et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015. April 28; 313 16: 1636- 1644. 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jones EB. Medication-assisted opioid treatment prescribers in federally qualified health centers: capacity lags in rural areas. J Rural Health. 2018. December; 34 1: 14- 22. 10.1111/jrh.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Louisiana Commission on Preventing Opioid Abuse. The Opioid Epidemic: Evidence-Based Strategies Legislative Report, April 2017. http://www.pharmacy.la.gov/assets/docs/Public_Library/LCPOA_FinalReportPublic_2017-0331.pdf. Published March 31, 2017. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- 57. Netherland J., Botsko M., Egan JE., et al. BHIVES Collaborative. Factors affecting willingness to provide buprenorphine treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009. April; 36 3: 244- 251. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatments for substance use disorders. https://www.samhsa.gov/treatment/substance-use-disorders. Updated August 9, 2016. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 59. Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. COR-12™ opioid treatment program: making a difference in Oregon. http://www.hazeldenbettyford.org/articles/2016-news/cor-12-opioid-treatment-making-a-difference. Published December 1, 2016. Accessed December 19, 2017.

- 60. Monico LB., Gryczynski J., Mitchell SG., Schwartz RP., O'Grady KE., Jaffe JH. Buprenorphine treatment and 12-step meeting attendance: conflicts, compatibilities, and patient outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015. October; 57: 89- 95. 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lofwall MR., Walsh SL. A review of buprenorphine diversion and misuse: the current evidence base and experiences from around the world. J Addict Med. 2014. Sep-Oct; 8 5: 315- 326. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bazazi AR., Yokell M., Fu JJ., Rich JD., Zaller ND. Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. J Addict Med. 2011. September; 5 3: 175- 180. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]