Abstract

Objective

Undiagnosed HIV continues to be a hindrance to efforts aimed at reducing incidence of HIV. The objective of this study was to provide an estimate of the HIV undiagnosed population in Catalonia and compare the HIV care cascade with this step included between high-risk populations.

Methods

To estimate HIV incidence, time between infection and diagnosis and the undiagnosed population stratified by CD4 count, we used the ECDC HIV Modelling Tool V.1.2.2. This model uses data on new HIV and AIDS diagnoses from the Catalan HIV/AIDS surveillance system from 2001 to 2013. Data used to estimate the proportion of people enrolled, on ART and virally suppressed in the HIV care cascade were derived from the PISCIS cohort.

Results

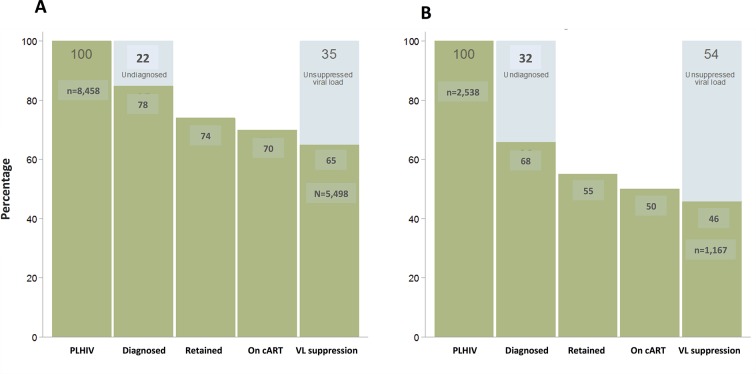

The total number of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Catalonia in 2013 was 34 729 (32 740 to 36 827), with 12.3% (11.8 to 18.1) of whom were undiagnosed. By 2013, there were 8458 (8101 to 9079) Spanish-born men who have sex with men (MSM) and 2538 (2334 to 2918) migrant MSM living with HIV in Catalonia. A greater proportion of migrant MSM than local MSM was undiagnosed (32% vs 22%). In the subsequent steps of the HIV care cascade, migrants MSM experience greater losses than the Spanish-born MSM: in retention in care (74% vs 55%), in the proportion on combination antiretroviral treatment (70% vs 50%) and virally suppressed (65% vs 46%).

Conclusions

By the end of 2013, there were an estimated 34 729 PLHIV in Catalonia, of whom 4271 were still undiagnosed. This study shows that the Catalan epidemic of HIV has continued to expand with the key group sustaining HIV transmission being MSM living with undiagnosed HIV.

Keywords: HIV surveillance, HIV undiagnosed infection, continuum of care, migrant, MSM, cascade

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of regular surveillance and cohort data gives high consistency of local estimates.

The use of the HIV Modelling Tool allowed calculating the first step of the HIV care cascade by region of origin and among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Catalonia.

The various subgroup analyses completed for this study may not necessarily explain complex differences in global HIV epidemic dynamics among migrants and MSM, but they do demonstrate that the key group sustaining HIV transmission is MSM living with undiagnosed HIV.

Linking surveillance and cohort dataset to population migration and death registries is weak in Catalonia; therefore, this information is poorly crossed between datasets, which can lead to misclassification of vital status or out-migration that might overestimate the number still alive and living in Catalonia.

Introduction

Undiagnosed HIV continues to be a hindrance to efforts aimed at reducing incidence of HIV. People who remain unaware of their HIV status for a long time have an increased risk of transmitting the virus to others.1 Some studies have shown that undiagnosed individuals may give rise to most new HIV transmissions,1 2 due to higher infectiousness because of elevated viral load at the time of HIV seroconversion3 or poor decisions related to their risk behaviours.4 Furthermore, undiagnosed individuals are also at risk of delayed diagnosis as they do not benefit from timely initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), experience higher HIV-related morbidity and higher mortality, being 11 times more likely to die within a year of being tested than if they had been tested after they were first exposed.5

In 2015, it was estimated that around 15%–16% (122 000/810 000) of people living with HIV (PLHIV) were unaware of their infection in the European Union and the European Economic Area (EU/EEA),6 7 with proportions ranging from 10% in Sweden,8 12% in both the Netherlands and Italy,9 10 17% in UK11 to 34% in France.12 Numbers reported from USA are similar to those in Western Europe, with 16.4% of the HIV-infected individuals being undiagnosed in 2013.13 In previous work on the Catalan HIV care cascade, we were not in the position to estimate this step, relying on average European estimates.14 The availability of the ECDC model15 means we now have a tool that is readily available and uses routinely available surveillance data to estimate undiagnosed HIV, time from infection to diagnosis and estimated annual incidence.

Estimates of the number of people in a country or region who have undiagnosed HIV are of paramount importance for understanding the burden of HIV, stimulating the early identification and treatment such people and informing strategic plans for the future delivery of cART.16 On the other hand, the use of the HIV treatment cascade as a straightforward guide to quantify population-level estimates of successive steps from diagnosis to viral suppression will facilitate measurement, monitoring and provision of HIV care. Therefore, the objective of this study was to provide an estimate of the HIV undiagnosed population in Catalonia, taking into account both men who have sex with men (MSM) and region of origin, using an ECDC model that uses routinely available surveillance data and compare the HIV care cascade with this step included between these two high-risk populations.

Methods

We undertook descriptive and comparative data analysis to identify differences in MSM stratified by migrant and Spanish-born populations. Migrants were defined as individuals born in a country other than Spain.

The primary data source was the unified Catalan HIV/AIDS surveillance system from 2001 to 2013.17 We extracted information on the date of HIV diagnosis, sex, age, transmission mode (people who inject drugs, heterosexual men, heterosexual women and MSM), CD4+ cell count and clinical stage at diagnosis. Late diagnosis and advanced HIV infection were defined as a CD4 cell count below 350 cells/mL or AIDS and CD4 cell count below 200 cells/mL or AIDS at the time of HIV diagnosis, respectively. Data used to calculate the number of PLHIV, the number of undiagnosed and diagnosed population and the time between infection and diagnosis were the annual number of new HIV diagnoses by CD4+ count stratum adjusted for delay in reporting and undernotification, the annual number of new AIDS cases and the annual number of concurrent HIV/AIDS diagnoses (an AIDS diagnosis within 6 weeks of HIV diagnosis).

Data used to estimate the proportion of people enrolled, on ART and virally suppressed in the HIV care cascade were derived from the PISCIS cohort, which includes data on over 17 000 HIV-positive people seen for follow-up from 1998 (coverage around 80%) in all of the participating centres in Catalonia and is fully described elsewhere.18 The first two steps of the HIV care cascade (PLHIV and diagnosed and proportion of undiagnosed population) were derived from the estimates calculated with the ECDC tool, whereas the last three were derived from the PISCIS cohort. Each of these steps was analysed by region of origin and by MSM.

Written informed consent and ethical approval were not obtained, as the data used were aggregate anonymised surveillance and HIV care information.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the distribution of sex, age, transmission mode and presentation with late and/or advanced HIV disease were assessed by region of origin, using Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables.

To estimate HIV incidence, time between infection and diagnosis and the undiagnosed population by CD4 count strata and its 95% CI, we used the ECDC HIV Modelling Tool V.1.2.2,15 which is based on a multistate back-calculation model that uses surveillance data on new HIV and AIDS diagnoses and that models the HIV incidence curve by cubic splines. The model is described in detail elsewhere.16 19 We considered four distinct historical periods for which CD4 stratum-specific diagnosis rates were estimated: (1) 1980–1984, during which the first AIDS cases were diagnosed; (2) 1985–1998, when serological testing for HIV became widely available; (3) 1999–2001, the start of the era of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART); (4) 2002–2013, the start of the HIV notification in Catalonia. Annual numbers of HIV diagnoses were available from 2001 onwards. The CD4 count at the time of diagnosis was defined as the first CD4 count after diagnosis and before start of treatment. Overall, 81.6% of the patients diagnosed from 2001 onwards had a CD4 count available at the time of diagnosis. The estimated annual numbers of diagnoses by CD4 count stratum were then fitted to the observed numbers. The number of HIV-infected who were still alive by the end of 2013 was estimated by subtracting the cumulative number of people who died from the cumulative number of HIV infections. The number of deaths among diagnosed people was taken from the Catalan HIV Surveillance System from 2001 to 2013.

The subsequent step of linked to care was calculated by applying to the preceding stage a proportion estimated from surveillance data. The proportions retained in care, on cART and virally suppressed were derived from the PISCIS cohort. A fuller description of the methods used has been published elsewhere.14 The level of significance was set at P value <0.05. Data analysis was performed using Stata V.12 (Stata, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

There were 10 150 new HIV diagnoses in adults (>18 years of age) reported to the Catalan National Surveillance System from 2001 to 2013; 60% of the cases were Spanish-born, 80.2% were men and the median age was 35 years old. The epidemiological profile of migrants was different to that of the Spanish-born population; there was a higher proportion of women (24.6% and 16.7%, respectively) and were younger at diagnosis (median age of 33 vs 37, respectively). In both migrants and the Spanish-born groups, the most frequent at-risk population was MSM (40% and 43%, respectively) (online supplementary table A).

bmjopen-2017-018533supp001.pdf (56.8KB, pdf)

Between 1980 and 2013, a cumulative number of 41 364 (95% CI 35 299 to 44 990) infections in the Catalan population were estimated to have occurred. The estimated number of new HIV infections peaked around 1988 with 3124 (95% CI 3031 to 3159) (figure 1A), declining nearly sevenfold, from 2674 (95% CI 2388 to 2663) in 1990 to 391 (95% CI 188 to 372) in 1999. From 2011, the estimated number of new infections started to peak up again reaching levels comparable with those in the mid-1990s, with the highest estimated number in 2013, 1120 (95% CI 461 to 1324). The estimated mean time between infection and diagnosis if diagnosis rates remain the same as in the year of infection is shown in figure 1B. Between 1980 and 1983, when HIV could only be diagnosed once AIDS symptoms appeared, the estimated average time between infection and HIV diagnosis for people infected in this period, where conditions have remained as they were in this period, would have been 11.6 years. This decreased to 4.7 years (95% CI 4.4 to 5.0) in the period 1984–1998. From 2000 onwards, the estimated time to HIV diagnosis steadily decreased to 3.9 (95% CI 3.6 to 4.6) years on average for the whole population in 2013. By region of origin, in both Spanish-born people and migrants, there was a similar decreasing trend in the estimated average time from infection to diagnosis until it reached 3.6 years (95% CI 3.4 to 3.8) and 4.7 years (95% CI 4.6 to 5.01), respectively in 2013. Figure 1C shows the estimated total number of PLHIV in Catalonia from 1980 to 2013, including those not yet diagnosed. Overall, there was an increasing trend throughout the time period, reaching the highest estimated number of people in 2013, a total of 34 729 (95% CI 32 740 to 36 827) PLHIV in Catalonia. Of these, 4271 (95% CI 3737 to 6252) were undiagnosed, a proportion of 12.3% (95% CI 11.8 to 18.1).

Figure 1.

Model outcomes for the total population in Catalonia, 1980–2013. (A) Estimated annual number of new HIV infections. (B) Estimated average time from HIV infection to diagnosis by year of infection. (C) Estimated total number of people living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections. (C) Estimated total number of people living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections.  Estimated total number of people living with HIV in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of people living with HIV in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of people diagnosed with HIV in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of people diagnosed with HIV in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of people undiagnosed with HIV in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of people undiagnosed with HIV in Catalonia.

In 2013, the estimated number of new infections among the Spanish-born population reached a number of 744 (95% CI 546 to 934) (figure 2A), while among the migrants was 376 new infections (95% CI 281 to 471). Finally among MSM, in both Spanish-born and migrants, there was a clear stepping increase in the estimated number of new infections from 2001, reaching the highest number in 2013, with 404 (95% CI 322 to 480) and with 227 (95% CI 163 to 310), respectively (table 1 and figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Model outcomes by region origin in Catalonia, 1980–2013. (A) Estimated annual number of new HIV infections among Spanish-born population. (B) Estimated annual number of new HIV infections among migrants. (C) Estimated total number of Spanish-born people living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections. (D) Estimated total number of migrants living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections.  Etimated total number of people living with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Etimated total number of people living with HIV by origin in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of people diagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of people diagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of people undiagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of people undiagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Table 1.

Estimated annual number of new HIV infections and new HIV, HIV/AIDS and AIDS diagnoses reported to the Catalan surveillance system, by year of infection and origin in MSM, Catalonia, 2001–2013

| Year | Estimated new HIV infection | New HIV diagnoses reported to the Catalan surveillance system | New HIV/AIDS diagnoses reported to the Catalan surveillance system | New AIDS diagnoses reported to the Catalan surveillance system | ||||||

| Spanish-born MSM | Migrants MSM | Spanish-born MSM | Migrants MSM | Spanish-born MSM | Migrants MSM | Spanish-born MSM | Migrants MSM | |||

| N | IC95% | N | IC95% | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| 2001 | 134 | (108 to 159) | 52 | (39 to 69) | 152 | 47 | 45 | 10 | 68 | 16 |

| 2002 | 151 | (127 to 172) | 74 | (63 to 90) | 175 | 62 | 41 | 16 | 55 | 19 |

| 2003 | 163 | (138 to 181) | 99 | (87 to 113) | 158 | 59 | 44 | 20 | 70 | 23 |

| 2004 | 172 | (156 to 188) | 126 | (113 to 141) | 185 | 89 | 28 | 14 | 52 | 23 |

| 2005 | 181 | (164 to 196) | 152 | (137 to 167) | 181 | 91 | 27 | 11 | 36 | 20 |

| 2006 | 191 | (174 to 210) | 176 | (159 to 192) | 187 | 109 | 26 | 18 | 52 | 16 |

| 2007 | 204 | (190 to 222) | 195 | (178 to 212) | 207 | 125 | 26 | 19 | 39 | 34 |

| 2008 | 222 | (209 to 238) | 209 | (195 to 225) | 183 | 133 | 19 | 17 | 35 | 27 |

| 2009 | 245 | (231 to 260) | 219 | (205 to 237) | 191 | 115 | 26 | 13 | 40 | 20 |

| 2010 | 274 | (255 to 296) | 225 | (204 to 249) | 224 | 175 | 24 | 22 | 34 | 38 |

| 2011 | 310 | (275 to 347) | 228 | (196 to 261) | 193 | 243 | 14 | 18 | 27 | 25 |

| 2012 | 353 | (298 to 408) | 228 | (183 to 283) | 282 | 189 | 19 | 10 | 35 | 22 |

| 2013 | 404 | (322 to 480) | 227 | (163 to 310) | 291 | 185 | 19 | 19 | 32 | 28 |

MSM, men who have sex with men.

By he estimated total number of PLHIV comparing the trend in the number of PLHIV between migrant and Spanish-born groups, it was observed that among locals there was a progressive but not very pronounced rise from 1991 to reach the highest estimated number in 2013 with 27 648 (95% CI 25 365 to 29 379) PLHIV, just 5.8% (95% CI 5.8 to 6.6) of whom were undiagnosed (1603, 95% CI 1421 to 1819) (figure 2C and D). Conversely, among migrants the estimated number of PLHIV rose steeply since the beginning of the epidemic, also reaching a peak in 2013 with 7081 (95% CI 6492 to 7616), but with four times the estimated undiagnosed population (23.4%, 95% CI 22.7 to 25.1) compared with the local population. Among (figure 3A and B) both local and migrant MSM, there has been a large increase in the estimated number of MSM living with HIV in the last 10 years, with a higher increasing slope among migrant MSM. By 2013, there were 8458 (95% CI 8101 to 9079) Spanish-born MSM and 2538 (95% CI 2334 to 2918) migrant MSM living with HIV in Catalonia, with 16.4% (95% CI 14.2 to 17.7) and 32.3% (95% CI 28.4 to 34.4) undiagnosed, respectively.

Figure 3.

Model outcomes for the MSM by origin in Catalonia, 1980–2013. (A) Estimated total number of Spanish-born MSM living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections. (B) Estimated total number of migrant MSM living with HIV, including diagnosed and undiagnosed HIV infections.  Estimated total number of MSM living with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of MSM living with HIV by origin in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of MSM diagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.

Estimated total number of MSM diagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia.  Estimated total number of MSM undiagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia. MSM, men who have sex with men.

Estimated total number of MSM undiagnosed with HIV by origin in Catalonia. MSM, men who have sex with men.

Data from the PISCIS cohort are available in online supplementary table B. Finally, figure 4A and B shows the differences in the HIV care cascade in MSM by origin. As a percentage of the total PLHIV, migrant MSM have a greater proportion undiagnosed (32% vs 16%) that local MSM. In subsequent steps in the HIV care cascade, migrant MSM experience greater losses due to the big different in the proportion of undiagnosed, when compared with the Spanish-born MSM, with lower proportion retained in care (74% vs 55%), on cART (70% vs 50%) and virally suppressed (65% vs 46%).

Figure 4.

Cascade of HIV care of MSM by region of origin in Catalonia, 2013. (A) Spanish-born MSM. (B) Migrants MSM. cART, combined antiretroviral therapy; MSM, men who have sex with men; PLHIV, people living with HIV; VL, viral load.

Discussion

Our study estimates that by the end of 2013, there were an estimated number of 34 729 PLHIV in Catalonia, Spain, of whom 4271 were still undiagnosed. This study also shows that migrants had a very high proportion of undiagnosed compared with Spanish-born population, and as it has been described by other sources of information from Catalonia,17 this study found that the Catalan epidemic of HIV has continued to expand during the past decade with the key group sustaining HIV transmission being MSM living with undiagnosed HIV and in the asymptomatic stage, especially migrants MSM.

The estimated overall prevalence of undiagnosed HIV-infected people in Catalonia (12.3%) is within the range of those recently obtained in other countries by 2013: 10% in Italy, 12% in Austria, 16% in Belgium and France, 17% in Germany, 18% in Spain and 19% in UK.7 Nevertheless, we think that some underestimation may have occurred due to two facts: first, that the method that we applied uses data on case reports, which may be subject to under-reporting, which can be ranged between 10% and 40%20 21 and can lead to underestimates HIV incidence and may also affect estimates of diagnosis rates and thus lower the per cent undiagnosed and second, by the fact that we could not feed the model with migration data. As Catalan epidemic is highly influenced by migration, we believe that this lowers the estimates of the annual number of new HIV infections and therefore undiagnosed HIV-infected individuals.

In line with our results, other studies also had identified among migrants a great proportion of undiagnosed.22 23 In Catalonia, this could be explained by the fact that migrants experienced a higher number of barriers to access HIV testing services than the Spanish-born population and that these needs might be driven primarily by shared risk factors.24 This also can be due to the fact that migrants face cultural and linguistic barriers as well as legal and administrative impediments to accessing health services and thus HIV testing facilities.25 In Europe, the HIV testing uptake among migrants range from 23% to 64%.25 This difference can differ by sex, as higher proportion of migrant women have been tested for HIV compared with men; this is partially owing to women’s acceptance of routine HIV screening during antenatal care. However, beyond this, several studies support a gender difference in HIV testing uptake, with migrant men being less exposed to HIV testing and less willing to be tested.25 However, this lower rate of HIV testing among migrant men might be more representative of migrant heterosexual men that MSM migrants, as these later perceive themselves as being at higher risk for HIV and thus being more likely to have ever been tested for HIV than the local MSM.26 27 But, it has been found that untested migrant MSM are particularly hard to reach,27 which is in line with our estimates.

Our results suggest that the Catalan HIV epidemic has been sustained by the HIV transmission among undiagnosed MSM, as it has been described in other studies in Catalonia.28 29 Consistent with this, in UK, using the same model it has been estimated that around two in three new infections were attributable to MSM living with undiagnosed HIV,30 and in Switzerland that around 82% of new cases among MSM were acquired from HIV undiagnosed men.31 This finding can be explained by an increase in risky sexual behaviours,32 33 including high prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse and increasing numbers of sexual partners.34 This is also supported by a recent survey that reported that 37% of MSM recruited in gay venues had not tested for HIV in the past 12 months.32 It has also been described that a great proportion of undiagnosed MSM have acquired the infection recently, which made them to be most infectious and the maintenance group of the HIV epidemic.34 The risky sexual conducts among migrant MSM have been also described, with higher prevalence of unprotected anal intercourse than Spanish-born MSM35 36 and specifically among Latin American MSM, high HIV prevalence rates among those diagnosed with syphilis and gonorrhoea, as well as, with high prevalence and incidence rates of STIs in those newly diagnosed with HIV.35 Resources should be allocated primarily to promote testing in high-activity MSM, as they are the key group sustaining the epidemic, and also for encouraging all MSM including migrants MSM to test regularly for HIV, and this includes design long-term sustainable outreach-based HIV interventions to reach as many MSM as we could for HIV testing.

Biomedical and behavioural interventions, targeting both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected MSM, should be used. In this regard, it will be essential to use interventions with proven efficacy, such as treatment as prevention, test and treat interventions, in combination with pre-exposure prophylaxis in highly adherent people, and to implement effective behavioural interventions that prevent an increase in risky behaviours, all of these intervention must be integrated in a well-designed strategy of combination prevention, as it has been described in other studies.37 Thus, in order to reduce the fraction of undiagnosed should be considered implementing and scaling up innovative approaches to promote greater access to and uptake of HIV testing by those most at risk, including community-based testing, home sampling, as well as indicator-condition-guided testing.

These results must be interpreted in light of several key methodological limitations. The use of the HIV Modelling Tool facilitated the standardisation of estimates for PLHIV; however, available information is partial and not representative of the different subpopulations of migrants and MSM across all Catalonia. Despite this limitation, this analysis allowed us to calculate the first step of the HIV care cascade by region of origin and among MSM in Catalonia. The various subgroup analyses completed for this study may not necessarily explain complex differences in global HIV epidemic dynamics among migrants and MSM, but they do demonstrate that the key group sustaining HIV transmission is MSM living with undiagnosed HIV and that among migrants testing coverage will need to be intensified and increased to find those undiagnosed. Although the use of PISCIS cohort data improved the consistency of the estimates, we are unable to link surveillance and cohort datasets to maximise internal consistency; therefore, we are unable to distinguish between those diagnosed and those linked to care (enrolled in the cohort), although linkage to care is expected to be high given the Catalan healthcare system characteristics and the high cohort coverage. Additionally, using a single viral load measurement may also overestimate durable viral suppression; however, they provide a snapshot of the continuum in 2013 which is simple to interpret and communicate to policy-makers, as it has been described by other authors.7 38 Finally, linking surveillance and cohort dataset to population migration and death registries is weak in Catalonia; therefore, this information is poorly crossed between datasets, which can lead to misclassification of vital status or out-migration that might overestimate the number still alive and living in Catalonia. Also, lack of reliable in-migration data complicated modelling of HIV incidence and the separation of earlier infections from new infections occurring after arrival within Catalonia. This demonstrates the urgent need to systematically incorporate longitudinal linked data across the different registries in the HIV information system aimed at monitoring and evaluate the HIV epidemic and its response at the local level.

In conclusion, our study suggests that about 4271 individuals living with HIV remained undiagnosed in Catalonia in 2013, with the greatest proportion among migrants and MSM from abroad and local. New screening strategies to further increase the offer and uptake of HIV testing and to reach out undiagnosed individuals are needed in order to reduce HIV transmission, targeting key population like migrants and MSM to ensure timely access to HIV care, to finally achieve global 90-90-90 targets to reduce HIV incidence and the number of persons remaining undiagnosed in Catalonia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank: The Catalan Public Health Agency, Catalan Government (Agència de SalutPública de Catalunya, Generalitat de Catalunya), the PISCIS Study Group for contributions of the PISCIS Cohort to model parameters and to colleagues in CEEISCAT who contributed HIV surveillance data inputs (Alexandra Montoliu, Cinta Folch and Laia Ferrer).

Footnotes

Contributors: CNJC and JMR-U developed the concept of the manuscript. They also carried out the modelling analysis and JMR-U and NV the remaining analysis. AE has calculated the adjustment for delayed reporting. JMR-U drafted the manuscript and integrated critical feedback from JA, CT, EF, GN, LF, IG, AM, JMV, PGdO, JAC, JMM and JC. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study received no specific grant from any funding agency. JMM received a personal intensification research grant #INT15/00168 during 2016 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain and a personal 80:20 research grant from the Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain during 2017–2019.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing jmreyes@iconcologia.net.

Collaborators: Coordinators: Jordi Casabona (Centre d’Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya: [CEEISCAT]-CIBERESP), Jose M. Miró (Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS, Universitat de Barcelona). Project coordinator: Juliana Reyes Ureña (CEEISCAT). Field coordinator: Andreu Bruguera Riera (CEEISCAT). Steering committee: Jordi Casabona, Alexandra Montoliu (CEEISCAT), Juliana Reyes (CEEISCAT), Esteve Muntada (CEEISCAT), Andreu Bruguera (CEEISCAT), Jose M. Miró (Hospital Clínic-IDIBAPS, Universitat de Barcelona), D. Podzamczer (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge-IDIBELL), Dr.Domingo (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), Josep M Llibre (Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol), Sio Riera (Hospital Son Espases de Mallorca), G. Navarro (Corporació Sanitària i Universitària Parc Taulí, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona), Cristina Cortés (Hospital General d’Hospitalet). Scientific committee: JM Gatell, C. Manzardo (Hospital Clínic-Idibaps, Universitat de Barcelona), B. Clotet (Fundació Lluita contra la Sida, Fundacio irsicaixa, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona), E. Ferrer (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge-IDIBELL), F. Segura (Corporació Sanitària i Universitària Parc Taulí, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona), L. Force (Hospital de Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme), J. Vilaró (Hospital General de Vic), A. Masabeu (Hospital de Palamós), E. Leon (Hospital General d’Hospitalet), C. Cifuentes, F Homar (Hospital Son Llàtzer), D. Dalmau, À. Jaen (Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa), Mª. Gracia Mateo, Mª del Mar Gutierrez, (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), V. Falcó, A. Curran (Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron), T. Puig (Hospital de Santa Maria) C. Agustí (CEEISCAT), F. Vidal, J Peraire (Hospital Joan XXIII), A. Orti (Hospital Verge de la Cinta de Tortosa), A. Almuedo (Hospital General de Granollers). Data Management and statistical analysis: A. Montoliu (CEEISCAT), E. De Lazzari (Hospital Clínic- Idibaps, Universitat de Barcelona), Dolors Giralt (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge-IDIBELL). Technical support: E. Loureiro (CEEISCAT), F. Gargoulas, (Hospital Son Espases y Hospital Son Llàtzer), JC Rubia (Hospital General d’Hospitalet), J Vilà (Serveis de Salut Integrats Baix Emporda). Participating physicians and centers: J. Ambrosioni, L. Zamora, J.L. Blanco, F. Garcia- Alcaide, E. Martínez, J. Mallolas, (Hospital Clínic- Idibaps, Universitat de Barcelona), G. Sirera, J. Romeu, A. Jou, E. Negredo, (Fundació Lluita contra la Sida, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona), M. Saumoy, A Imaz, F. Bolao, C. Cabellos, C. Peña, S. DiYacovo, E. Van Den Eynde (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge-IDIBELL), M. Sala, M. Cervantes, M.J. Amengual, M. Navarro, V. Segura (Corporació Sanitària i Universitària Parc Taulí, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona,) P. Barrufet, (Hospital de Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme), T. Payeras (Hospital Son Llàtzer), M. Gurgui, (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), L. Utrillo, (Hospital de Santa Maria). Civil society representatives: Sebastián Meyer (Comitè 1er de Desembre/Stop Sida) & Juanse Hernández (Comitè 1er de Desembre /gTt).

References

- 1.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. . Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1337–44. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006;20:1447–50. 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. . Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365:493–505. 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, et al. . Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;39:446–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National AIDS Trust. Latest UK statistics. 2013. http://www.nat.org.uk/HIV-Facts/ (accessed 26 Sep 2016).

- 6.Pharris A, Quinten C, Noori T, et al. . Estimating HIV incidence and number of undiagnosed individuals living with HIV in the European Union/European Economic Area, 2015. Euro Surveill 2016;21:30417 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.48.30417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gourlay A, Noori T, Pharris A, et al. . The HIV continuum of care in European Union countries in 2013: data and challenges. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:1644–56. 10.1093/cid/cix212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gisslén M, Svedhem V, Lindborg L, et al. . Sweden, the first country to achieve the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/World Health Organization (WHO) 90-90-90 continuum of HIV care targets. HIV Med 2017;18:1–3. 10.1111/hiv.12431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Sighem AI, Boender TS, Wit F, et al. ; Monitoring Report 2016. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection in the Netherlands. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Amsterdam: Stichting HIV Monitoring, 2016. https://www.hiv-monitoring.nl/index.php/download_file/force/1066/202/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mammone A, Pezzotti P, Regine V, et al. . How many people are living with undiagnosed HIV infection? An estimate for Italy, based on surveillance data. AIDS 2016;30:1131–6. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skingsley A, Yin Z, Kirwan P, et al. . HIV in the UK – Situation Report 2015 Incidence, prevalence and prevention. London, 2015. https://www.google.es/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=6&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjk9tvK7J7UAhWGmBoKHUF0BZUQFghFMAU&url=http%3A%2F%2Fifp.nyu.edu%2F2015%2Fgrey-literature%2Fhiv-in-the-uk-situation-report-2015-incidence-prevalence-and-prevention%2F&u [Google Scholar]

- 12.Supervie V, Ndawinz JD, Lodi S, et al. . The undiagnosed HIV epidemic in France and its implications for HIV screening strategies. AIDS 2014;28:1797–804. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song R, Hall HI, Green TA, et al. . Using CD4 data to estimate HIV Incidence, prevalence, and percent of undiagnosed infections in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74:3–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell CN, Ambrosioni J, Miro JM, et al. . The continuum of HIV care in Catalonia. AIDS Care 2015;27:1449–54. 10.1080/09540121.2015.1109584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). HIV Modelling Tool. 2016. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/aids/Pages/hiv-modelling-tool.aspx

- 16.van Sighem A, Nakagawa F, De Angelis D, et al. . Estimating HIV Incidence, Time to Diagnosis, and the Undiagnosed HIV Epidemic Using Routine Surveillance Data. Epidemiology 2015;26:653–60. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centre d’Estudis Epidemiològics sobre les Infeccions de Transmissió Sexual i Sida de Catalunya. Sistema integrat de vigilància epidemiològica de la SIDA/HIV/ITS a Catalunya (SIVES). Barcelona, 2015. http://www.ceeiscat.cat/documents/sives2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Á J, Casabona J, Esteve A, et al. . Clinical-epidemiological characteristics and antiretroviral treatment trends in a cohort of HIV infected patients. The PISCIS Project. Med Clin 2005;124:525–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birrell PJ, Gill ON, Delpech VC, et al. . HIV incidence in men who have sex with men in England and Wales 2001-10: a nationwide population study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:313–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70341-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EuroHIV. EuroHIV 2006 survey on HIV and AIDS surveillance in the WHO European Region, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control WRO for E. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe 2014. Stockholm, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Op de Coul EL, Schreuder I, Conti S, et al. . Changing patterns of undiagnosed HIV infection in the Netherlands: Who benefits most from intensified HIV test and treat policies? PLoS One 2015;10:1–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0133232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parés-Badell O, Espelt A, Folch C, et al. . Undiagnosed HIV and Hepatitis C infection in people who inject drugs: From new evidence to better practice. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;77:13–20. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reyes-Urueña J, Campbell C, Hernando C, et al. . Differences between migrants and Spanish-born population through the HIV care cascade, Catalonia: an analysis using multiple data sources. Epidemiol Infect 2017;145:1670–81. 10.1017/S0950268817000437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez-del Arco D, Monge S, Azcoaga A, et al. . HIV testing and counselling for migrant populations living in high-income countries: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:1039–45. 10.1093/eurpub/cks130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyos J, Fernández-Balbuena S, de la Fuente L, et al. . Never tested for HIV in Latin-American migrants and Spaniards: prevalence and perceived barriers. J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:18560 10.7448/IAS.16.1.18560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernández-Dávila P, Folch C, Ferrer L, et al. . Who are the men who have sex with men in Spain that have never been tested for HIV? HIV Med 2013;14(Suppl 3):44–8. 10.1111/hiv.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferrer L, Furegato M, Foschia JP, et al. . Undiagnosed HIV infection in a population of MSM from six European cities: results from the Sialon project. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:494–500. 10.1093/eurpub/cku139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folch C, Ferrer L, Montoliu A, et al. . Sexual behaviour and HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Catalonia, Spain 29th European Conference on Sexually Transmitted Infections. Sitges, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Punyacharoensin N, Edmunds WJ, De Angelis D, et al. . Modelling the HIV epidemic among MSM in the United Kingdom. AIDS 2014;29:1 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Sighem A, Vidondo B, Glass TR, et al. . Resurgence of HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Switzerland: mathematical modelling study. PLoS One 2012;7:e44819 10.1371/journal.pone.0044819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Folch C, Munoz R, Zaragoza K, et al. . Sexual risk behaviour and its determinants among men who have sex with men in Catalonia, Spain. Euro Surveill 2009;14:19415 10.2807/ese.14.47.19415-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folch C, Fernández-Dávila P, Ferrer L, et al. . High prevalence of drug consumption and sexual risk behaviors in men who have sex with men. Med Clin 2014;47:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aghaizu A, Wayal S, Nardone A, et al. . Sexual behaviours, HIV testing, and the proportion of men at risk of transmitting and acquiring HIV in London, UK, 2000-13: a serial cross-sectional study. Lancet HIV 2016;3:e431–e440. 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30037-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diaz A, Junquera ML, Esteban V, et al. . HIV/STI co-infection among men who have sex with men in Spain. Euro Surveill 2009;14:19426 10.2807/ese.14.48.19426-en [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Robertson AM, et al. . High prevalence of multiple syndemic conditions associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among a large sample of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking men who have sex with men in Latin America. Arch Sex Behav 2015;44:1869–78. 10.1007/s10508-015-0488-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okano JT, Robbins D, Palk L, et al. . Testing the hypothesis that treatment can eliminate HIV: a nationwide, population-based study of the Danish HIV epidemic in men who have sex with men. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:789–96. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30022-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crepaz N, Tang T, Marks G, et al. . Durable Viral Suppression and Transmission Risk Potential Among Persons With Diagnosed HIV Infection: United States, 2012-2013. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:976–83. 10.1093/cid/ciw418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018533supp001.pdf (56.8KB, pdf)