Abstract

Objective

To define a standard set of outcomes and the most appropriate instruments to measure them for managing newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

Methods

A literature review and five discussion groups facilitated the design of two-round Delphi questionnaire. Delphi panellists (haematologists, hospital pharmacists and patients) were identified by the scientific committee, the Spanish Program of Haematology Treatments Foundation, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacies and the Spanish Community of Patients with MM. Panellist’s perception about outcomes’ suitability and feasibility of use was assessed on a seven-point Likert scale. Consensus was reached when at least 75% of the respondents reached agreement or disagreement. A scientific committee led the project.

Results

Fifty-one and 45 panellists participated in the first and second Delphi rounds, respectively. Consensus was reached to use overall survival, progression-free survival, minimal residual disease and treatment response to assess survival and disease control. Panellists agreed to measure health-related quality of life, pain, performance status, fatigue, psychosocial status, symptoms, self-perception on body image, sexuality and preferences/satisfaction. However, panellist did not reach consensus about the feasibility of assessing in routine practice psychosocial status, symptoms, self-perception on body image and sexuality. Consensus was reached to collect patient-reported outcomes through the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ) Core questionnaire 30 (C30), three items from EORTC-QLQ-Multiple Myeloma (MY20) and EORTC-QLQ-Breast Cancer (BR23), pain Visual Analogue Scale, Morisky-Green and ad hoc questions about patients’ preferences/satisfaction.

Conclusions

A consensual standard set of outcomes for managing newly diagnosed patients with MM has been defined. The feasibility of its implementation in routine practice will be assessed in a future pilot study.

Keywords: multiple myeloma, outcome, patient‐centered, standardisation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first initiative to carry out a standardisation process for multiple myeloma (MM).

A broad consensus has been achieved with the participation of >50 patients and health professionals.

Highly qualified experts in MM were identified by the scientific committee, the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacies, the Spanish Program for Haematology Treatments Foundation and the Spanish Community of Patients with MM.

Although most of the selected instruments are validated, the set as a whole has not been.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 1% of all cancers and represents 13% of all haematological malignancies.1 It is estimated that about 86 000 new cases of MM and 63 000 deaths occur annually worldwide.2 The incidence of MM increases with age, therefore, an ageing population has led to an increase of new diagnoses of MM in the last decades3 and potentially will continue to rise in the coming years. Despite the substantial advances in treatment options, MM remains incurable with a short median survival (6–7 and 2 years for standard-risk and high-risk patients, respectively).2 4 Moreover, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with MM is commonly affected by symptoms associated with the disease itself and the toxicity of the treatment.5 6

Quality healthcare encompasses not only achieving disease remission, but also easing patients’ discomfort and helping them manage their disease. Emerging strategies encourage maximising the value for patients (achieving the best outcomes at the lowest cost), moving towards a patient-centred system organised around patients’ needs.6 To do this effectively and efficiently requires an integrative approach. Thus, collecting holistic outcomes data from patients is crucial. Assessing regularly patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in clinical practice, complementary to the use of traditional biomedical markers, could contribute to this convergence improving MM management.7–9 From the point of view of a healthcare provider, this approach could lead to institutional improvements, foster the dissemination of best practices and prompt competition around value.

During the last years, efforts have been made to quantify MM outcomes accurately using validated instruments.10 This has led to a wide variability across instruments and variables. Paradoxically, the broad range of instruments and variables hinder outcome comparisons between physicians, institutions and regions. As a result, the current goal is not so much a question of developing new outcome measures, but to agree on which ones are well validated and should be used. Pioneer initiatives such as the one performed by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) have focused on this concern, developing standard sets for various diseases, among which MM is not included.11

In collaboration with the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacies (SEFH) and the Spanish Program for Haematology Treatments Foundation (PETHEMA), we aim to cover the existing needs defining a set of global standards for collecting outcomes that matter most to patients with MM, and select a proper instrument for the measurement of these outcomes.

Methods

The study comprised three phases: (1) literature review; (2) discussion groups; (3) Delphi consultation.

Scientific committee

A scientific committee led and coordinated the project. It consisted of five highly qualified experts in MM: two haematologists and two hospital pharmacists with extensive experience in MM, and one patient with MM. They were chosen on the basis of their long-standing expertise in MM management.

Literature review

A literature search was performed to identify clinical outcomes and PROs, and instruments to measure them used in clinical practice for the management and follow-up of patients with MM. The search included original articles, systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines published in English or Spanish between January 2010 and October 2015. The information obtained in the literature review was used to steer five discussion groups. Presetting of instruments was done by the scientific committee considering the availability of a validated version in the Spanish population, the level of evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence) of the reviewed studies and their agreement of its use (according to bibliography references). Consensus of three-fourth was necessary for inclusion.

Discussion groups

The objective of the discussion groups was to share experiences and opinions about outcome variables, definitions, measures of relevance and to establish the target population, in order to designate the consensual outcomes. Haematologists and pharmacists covered all topics (clinical and PROs), while patients covered only PROs. Outcomes and instruments were appraised according to their use in the Spanish routine clinical practice (expert opinion), the simplicity of completion and the grade of disease’s impact on the variables from patient’s view. From March to April 2016, different discussion groups were held: three with haematologists (n=4) and hospital pharmacists (n=4), and two with patients with MM (n=7). Patients were divided in two groups of three and four people to facilitate discussion about their perspective of general MM management and PROs.

The information obtained in the discussion groups was used to design the Delphi questionnaire.

Variables and instruments that achieved consensus for their inclusion (three-fourth) and those controversial (half), were included in Delphi consultation.

Delphi consultation

A national two-round Delphi consultation was conducted to establish consensus regarding the most important outcome variables and their proper measurements for managing MM. The Delphi technique is a structured process that consists of the application of subsequent questionnaires in a series of rounds in which the group’s responses to one round are used to produce the questionnaire for the next round, providing feedback to respondents in each consecutive round.12

Contents of the Delphi consultation: first and second questionnaires

Four groups of categories were addressed in the first questionnaire: basal variables of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (9 issues), follow-up clinical variables (6 issues), follow-up treatment variables (1 issue) and follow-up patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) variables (10 issues). Affirmative statements assessed the participants’ perception related to outcome suitability and feasibility for use in routine clinical practice (within a 5-year period), on a seven-point Likert scale (from ‘1=in total disagreement’ to ‘7=in total agreement’). The scientific committee reviewed the questionnaire to ensure that the statements were clear, unambiguous and non-leading.

The second questionnaire included all statements for which consensus was not reached in the first round. Each Delphi panellist obtained their own score and the average score given by the whole group for the same statement in the previous round.

Delphi panellists

Delphi panellists (haematologists, hospital pharmacists and patients with MM involved in MM management) were identified by the scientific committee, PETHEMA Foundation, SEFH and the Spanish Community of Patients with MM (CEMMp). Participants were invited by email receiving the link of the study, username and password (unique for each participant).

Consensus definition

The definition of consensus was established before data analyses, according to the common criteria.12 Consensus was reached for each statement when at least 75% of the respondents concurred (entirely agree, mostly agree or somewhat agree) or disagreed (entirely disagree, mostly disagree or somewhat disagree).

Data analysis

The percentage of participants who selected each option and percentile distributions (25, 50 and 75) were calculated using STATA statistical software, V.14. The percentages described in the text refer to the final scores (score of the round in which consensus was achieved for each question (first or second) or second round in the event that consensus was not reached).

Results

We performed an in-depth literature search identifying almost 40 outcomes and more than 70 instruments. In fact, the biggest challenge was to choose from the huge variety of variables, especially for PROMs. The whole outcomes, clinical instruments and 30 PROMs were preselected by the scientific committee. From those, 18 follow-up variables and 21 instruments were included in Delphi consultation after deliberation in discussion groups. The standard set includes 15 follow-up variables and 18 measure instruments.

The number of panellists who participated in the first and second Delphi rounds were: 51 (20 haematologists, 24 hospital pharmacists and 7 patients) and 45 (18 haematologists, 22 hospital pharmacists and 5 patients), respectively.

Condition scope

The participants in the discussion groups agreed that the patients with newly diagnosed MM would be the target population for the MM standard set. This comprised those patients eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation and those who were not, and covering induction, consolidation and maintenance treatments. Thus, a broad range of stages of the disease and its treatments could be followed by means of active surveillance.

Outcome domains and measures

Survival and disease control

Due to the high mortality rate and short life expectancy of patients with MM, the health professionals who participated in the discussions group preselected the following variables: overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), minimal residual disease (MRD) and response criteria (RC). Treatment efficacy would be measured by the RC according to the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG). Subsequently, the expert panellists also agreed to include these variables in the MM standard set (table 1).

Table 1.

Basal and follow-up variables, instruments and timing for registering them

| Measure | Details/instrument | Timing | Data source |

| Basal characteristics | |||

| Age | Data of birth | Basal | CD |

| Gender | Gender (male/female) | Basal | CD |

| Ethnicity | Race | Basal | CD |

| Family history | Family history of myeloma or other type of cancer | Basal | CD or PR |

| ISSr | International Staging System (revised) | Basal | CD |

| Renal failure | Renal failure prior to treatment/creatinine clearance | Basal | CD |

| Anaemia | Anaemia prior to treatment/haemoglobin | Basal | CD |

| Bone lesions | Number and location/X-ray, PET etc | Basal | CD |

| Neuropathies | Neuropathies prior to treatment | Basal | CD |

| Comorbidities | Comorbidities and/or other non-related myeloma diseases | Basal | CD |

| Type of treatment | Type of treatment initiated (standard or not) | After deciding to treat | CD |

| Survival and disease control | |||

| OS | Overall survival/data of diagnosis and death | Basal, death | CD or AD |

| PFS | Progression-free survival/from treatment initiation to progression or death. | Treatment initiation, progression or death | CD |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease/flow cytometry: 4–8 colours panel | When complete remission was reached | CD |

| Treatment response | Time for best response, according to the IMWG | Monthly during treatment, and then every 2–3 months | CD |

| Complications | |||

| Treatment and adverse events | Completed treatment (with or without dosage reduction) and side effects that hamper the patient’s daily activities or those that imply changes in the pattern of treatment/registry | Monthly during treatment, and then every 2–3 months | CD |

| PROMs and PREMs | |||

| Treatment adherence | Morisky-Green+dispensing control | At each dispensation | CD or PR |

| HRQoL | Health-related quality of life/EORTC-QLQ-C30 | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Pain | Pain intensity/EORTC-QLQ-C30 (pain scale)+VAS |

VAS: basal, before treatment, monthly during treatment and following every 3 months. EORTC-QLQ-C30: basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Performance status | Patients’ level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themselves, daily activity and physical ability/EORTC-QLQ-C30 (physical functioning and role functioning scales)+ECOG |

ECOG: basal, before treatment, monthly during treatment and following every 3 months. EORTC-QLQ-C30: basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

CD and PR |

| Asthenia/fatigue | Weakness or general asthenia that makes it difficult to perform tasks that are normally done easily/EORTC-QLQ-C30 (fatigue scale) | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Psychosocial status | Impact of disease on cognitive, emotional and social skills/EORTC-QLQ-C30 (emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning) | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Symptoms | Intensity of symptoms due to illness or treatment/EORTC-QLQ-C30 (symptoms scales) | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Preferences and satisfaction | Ad hoc items | Preferences: prior to first visit Satisfaction: after treatment |

PR |

| Body image | Self-perception of body image/EORTC-QLQ-MY20 (body image scale) | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

| Sexuality | Self-perception on sexual life/adapted from EORTC-QLQ-BR23 (sexual functioning scale) | Basal Treatment: before and after treatment. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), every 2–3 months Follow-up/maintenance: every 6 months |

PR |

AD, administrative data; CD, clinical data; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EORTC-QLQ-BR23, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Breast Cancer; EORTC-QLQ-C30, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core questionnaire; EORTC-QLQ-MY20, European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Multiple Myeloma; HRQoL, Health Related Quality of Life; IMWG, International Myeloma Working Group; ISSr, International Staging System (revised); MRD, minimal residual disease; OS, overall survival; PET, positron emission tomography; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, patient reported; PREMs, patient-reported experience measures; PROMs, patient-reported outcome measures; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

The panellists also reached consensus regarding the inclusion of the M-protein and plasma cell immunophenotype. However, considering that these variables are instruments integrated in other outcome variables, such as International Staging System (ISS) or RC, the scientific committee agreed to discard them to avoid duplicities and to optimise the set.

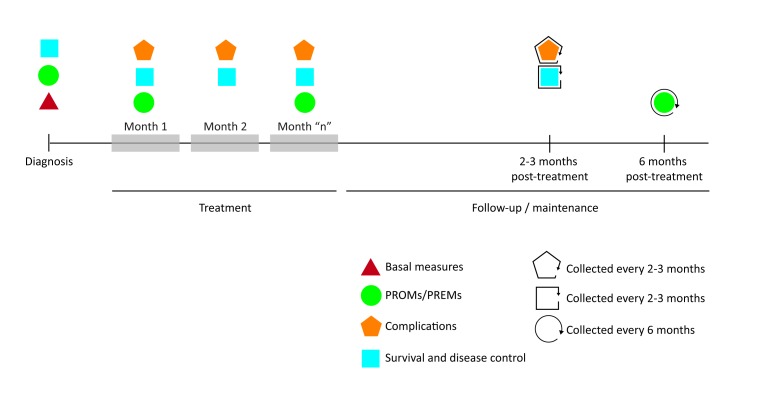

Consensus was reached in collecting OS (from diagnosis to death), PFS (from the beginning of the treatment to disease progression or death), MRD (when/if patient achieved complete remission) and treatment response (monthly during treatment and subsequently every 2 or 3 months) (table 1 and figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline illustrating when the key outcomes should be collected. PREM, patient-reported experience measure; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure.

Complications

Completed treatment and side effects

The participants in the discussion group considered that the side effects of MM treatments were important outcomes since they commonly cause considerable morbidity and low HRQoL in patients with MM.5 13 14 To facilitate data collection, the health professionals proposed a simplified version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events V.4,15 clustering them into general categories (bone marrow suppression, constitutional, cardiovascular, hepatic, renal, neurological, gastrointestinal, skin, infection and others). The Delphi panellists agreed to collect each completed treatment (with or without dosage reduction) and those side effects that hamper the patient’s daily activities or those that imply changes in the treatment pattern (table 1). Consensus was achieved to collect this information monthly during treatment and every 2 or 3 months during periods without treatment (table 1 and figure 1).

PROs and patient-reported experiences

Adherence

The Delphi panellists agreed on an adherence multimeasure approach, including the self-reported Morisky-Green questionnaire (four items) and dispensing control performed by hospital pharmacists in each medication provision.

PROs

HRQoL and other existing PROs identified in the literature (such as pain, functional status, fatigue, symptoms and psychosocial status) were considered of importance during the discussion groups. Moreover, patients expressed the relevance of their perception of body image and sexuality. The health professionals participating in the discussion groups recommended the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)-Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ)-Core questionnaire (C30) as the PROM covering most of these variables. This questionnaire covers the most important domains (general HRQoL, pain, functional status, fatigue, symptoms and psychosocial status) and it is a validated tool that is internationally recognised and available in many languages.16 The expert participants in the discussion groups were aware that the EORTC-QLQ-Multiple Myeloma (MY20) module17 or Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Multiple Myeloma (FACT-MM)18 includes questions that specifically target MM aspects. However, trying to balance feasibility of use and essential information, the use of the EORTC-QLQ-C30 alone was considered the best balanced choice, since it is widely used for other type of cancer.

The panellists agreed to collect HRQoL, pain, functional status, fatigue, symptoms and psychosocial status with the EORTC-QLQ-C30. They also agreed to collect self-perception of body image with the Body Image Scale (one item) of the EORTC-QLQ-MY20, and sexuality by two sexuality items adapted from the EORTC-QLQ-Breast Cancer (BR23).19 Furthermore, due to the high relevance of pain intensity and functional status in patients with MM, the panellists agreed to collect them with the EORTC-QLQ-C30 plus other straightforward and rapid tools: the pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) test,20 respectively. Despite the panellists agreeing to collect all these PROMs, there was no consensus as to the feasibility of measuring some of them in routine clinical practice during the next 5 years. Specifically, consensus was not reached for psychosocial status (71.1%), symptoms (73.3%), body image (64.4%) and sexuality (66.7%).

The panellists reached consensus in assessing PROMs at baseline (diagnostic), before and after the treatment and subsequently every 6 months during follow-up/maintenance. In continuous and long-term treatments (>6 months), the assessment would be performed every 2-3 months. The pain VAS and the ECOG test would be collected in the same time frame than the EORTC-QLQ-C30, and additionally monthly during treatment.

Preference and satisfaction

The Delphi panellists agreed to collect the patient preferences and satisfaction. Preferences (about the information they would like to receive and about their preferred role in the decision-making) and satisfaction (about the same questions) will be processed with a short ad hoc questionnaire. Whereas preferences will be assessed prior to the first consultation, satisfaction will be assessed after the treatment.

Nevertheless, consensus about the feasibility of collecting them in routine clinical practice was not reached (73.3%).

Basal characteristics

Considering that baseline clinical and sociodemographic factors are related to both disease control and PROs outcomes,21 22 participants in the discussion groups perceived their inclusion in Delphi consultation necessary.

The expert panellists agreed to collect age, gender, ethnicity, family history and stage of the disease. Regarding the latter, consensus was reached to use the revised ISS for MM, recently proposed by the IMWG as a simple and powerful prognostic staging system for newly-diagnosed MM.22 However, due to the current barriers that exist in some centres to accurately detect chromosomal abnormalities, the panellists agreed to use the traditional ISS in these cases. In addition, it was agreed to collect renal failure, anaemia, bone lesions, neuropathies and comorbidities not associated to MM before the treatment initiation, since disease progression and treatment toxicity could alter these issues during the follow-up. All basal characteristics that reached consensus are listed in table 1.

Discussion

Healthcare systems are currently experiencing a critical shift in their model towards a patient-centred system.6 However, value-based healthcare has to deal with barriers such as the absence of standardised outcomes that are meaningful for patients,23 which hampers the comparison of results between providers, physicians and regions. Standardisation favours simplicity and minimises variations allowing comparing results, at the same time as aligning all different collectives involved in the management of MM towards a common goal: to improve healthcare quality. At present, there are no commonly accepted standards for defining the optimal outcome parameters for use in patients with MM. A minimum standard set of important outcomes for patients with MM could help to improve healthcare quality, supporting informed decision-making and reducing healthcare costs.

In recent years, several initiatives led by the ICHOM have developed standard sets of health outcomes for a wide variety of diseases including prostate cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, coronary artery diseases, stroke, Parkinson, hip and knee osteoarthritis, dementia and depression.11 Recently, some institutions and registries that measure health outcomes, such as Ramsay Healthcare, Fortis Healthcare and Mayo Clinic, have started a second phase implementing some of these standard sets.24 Some promising early results concerning these implementations have been recently published. The use of the cleft lip and palate standard set at the Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands has shown a high compliance with the proposed measures (90%–100%) and good positive feedback from both patients and clinicians.25 The implementation of a standard set for Parkinson’s disease at Aneurin Bevan University Health Board in South Wales showed similar results after optimising the electronic forms.26 Another example is the use of the ICHOM Standard Set for coronary artery disease implemented in the Coronary Angiogram Database of South Australia. This initiative has allowed the standardisation of procedures for percutaneous coronary intervention among hospitals, increasing radial access and reducing bleeding-related complications.27

To our knowledge, our project is the first initiative to carry out a standardisation process for MM. We performed an in-depth literature search identifying almost 40 outcomes and more than 70 instruments. In fact, the biggest challenge was to choose from the huge variety of variables, especially for PROMs. HRQoL is particularly relevant for patients with MM taking into account that many of them, especially the older ones, consider HRQoL even more important than overall survival.28 During the discussion groups, patients also recommended the inclusion of self-perception of body image and sexuality, which are usually evaluated in routine clinical practice for other malignant diseases such as breast cancer but not for MM. Regarding to the recording of treatment adherence, consensus was achieved. It could be thought that the treatment for serious diseases present high rates of adherence. However, it is important to note that non-adherence to oral drugs could be really low,29 leading to suboptimal drug efficacy, poor clinical outcomes and increased healthcare costs.30

The minimum set of standardised outcome measures was compiled from the perspectives of more than 50 participants, including expert health professionals (haematologists and hospital pharmacists) and patients with MM. The broad consensus reached is the main strength of this study. However, a number of limitations remain present. Although most of the selected instruments are validated, the set as a whole has not been, which is one of the main limitations of the present study. In addition, the standard set is derived from expert consensus rather than high levels of evidence. Moreover, new therapies have risen the mean overall survival to 6–7 years.4 Thus, develop an outcome set covering all disease stages, and not only those targeting newly diagnosed patients, would be interesting for future work.

These recommendations represent an initial approach for collecting a minimum standard set of outcomes for MM management. Nonetheless, future steps should be taken to validate the standard set and refine it towards a global standard. We are aware that the burden of answering all proposed items at each interval could be significant for some patients. Likewise, data input could represent an additional workload for health professionals. In fact, when holding discussion groups, health professionals were of the opinion that its acceptance could be associated with the time-consuming process. In this sense, an electronic questionnaire directly filled in by patients and the easy inclusion of the results in their medical history could guarantee broad acceptance. In addition, future computer-adaptive PROMs would decrease respondent burden30 and smartphone or telehealth surveys would pave the way towards piloting inexpensive forms of digital data collection.2 In this sense, the feasibility of the MM standard set should be evaluated via a pilot study using the set in routine clinical practice.

Summary

It has been defined a minimum recommended set of consensus outcomes, including clinical and PROs, to be collected for patients with MM in routine clinical practice. The use of this standard set would allow learning from each other through meaningful comparison, helping to improve MM management and developing a quality and cost-effective patient-centred healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Spanish Community of Patients with MM, its president Teresa Regueiro-López, the SEFH and the PETHEMA for their support. Also, we thank Dr Hernández-Rivas, Dr Mateos, Dr Hernández, Dr Ríos-Tamayo, Dr Lamas, Dr Mosquera, Dr Mangues, Dr Delgado, Dr Herreros and the participating patients for their contribution in the discussion groups.

Footnotes

Contributors: JB, MAC, JJL and JLP: coordinated the project, assisted in the identification of participants, and was involved in design of study, construction of the Delphi questionnaire, interpretation of results and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. LL: designed the study, was involved in the construction of the Delphi questionnaire, interpretation of results and drafted the manuscript. HDdP: was involved in data collection, data analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: This work has been supported by the Spanish Program of Haematology Treatments Foundation (PETHEMA) and the Spanish Society of Hospital Pharmacies (SEFH).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data from the study are available.

References

- 1.Howlade N, Noone A, Krapcho M. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2009 (vintage 2009 populations). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwamm LH. Telehealth: seven strategies to successfully implement disruptive technology and transform health care. Health Aff 2014;33:200–6. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turesson I, Velez R, Kristinsson SY, et al. Patterns of multiple myeloma during the past 5 decades: stable incidence rates for all age groups in the population but rapidly changing age distribution in the clinic. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:225–30. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent Rajkumar S. Multiple myeloma: 2014 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2014;89:998–1009. 10.1002/ajh.23810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonneveld P, Verelst SG, Lewis P, et al. Review of health-related quality of life data in multiple myeloma patients treated with novel agents. Leukemia 2013;27:1959–69. 10.1038/leu.2013.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsenthaler C, Osborne TR, Gao W, et al. The impact of disease-related symptoms and palliative care concerns on health-related quality of life in multiple myeloma: a multi-centre study. BMC Cancer 2016;16:427 10.1186/s12885-016-2410-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giesinger JM, Kuijpers W, Young T, et al. Thresholds for clinical importance for four key domains of the EORTC QLQ-C30: physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue and pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;14:87 10.1186/s12955-016-0489-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:102 10.1186/1477-7525-7-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kvam AK, Wisløff F, Fayers PM. Minimal important differences and response shift in health-related quality of life; a longitudinal study in patients with multiple myeloma. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:79 10.1186/1477-7525-8-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osborne TR, Ramsenthaler C, Siegert RJ, et al. What issues matter most to people with multiple myeloma and how well are we measuring them? A systematic review of quality of life tools. Eur J Haematol 2012;89:437–57. 10.1111/ejh.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). 2016. http://www.ichom.org/ (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 12.Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:401–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloot S, Boland J, Snowden JA, et al. Side effects of analgesia may significantly reduce quality of life in symptomatic multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional prevalence study. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:671–8. 10.1007/s00520-014-2358-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colson K. Treatment-related symptom management in patients with multiple myeloma: a review. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1431–45. 10.1007/s00520-014-2552-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute NC. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). version 4.0. USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009:196. [Google Scholar]

- 16.EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC QLQ-C30. 2017. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/eortc-qlq-c30 (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 17.EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC MY20 module. 2017. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/specimen_my20_english.pdf (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 18.Wagner LI, Robinson D, Weiss M, et al. Content development for the functional assessment of cancer therapy-multiple myeloma (FACT-MM): use of qualitative and quantitative methods for scale construction. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:1094–104. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjelic-Radisic V, Arraras J, Bleiker E, et al. Breast (QLQ-BR23) Module. 2017. http://groups.eortc.be/qol/sites/default/files/img/slider/specimen_br23_english.pdf (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 20.Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. ECOG Scale of Performance Status. 2017. http://ecog-acrin.org/resources/ecog-performance-status (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 21.Terpos E, Berenson J, Cook RJ, et al. Prognostic variables for survival and skeletal complications in patients with multiple myeloma osteolytic bone disease. Leukemia 2010;24:1043–9. 10.1038/leu.2010.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Poel MW, Oerlemans S, Schouten HC, et al. Elderly multiple myeloma patients experience less deterioration in health-related quality of life than younger patients compared to a normative population: a study from the population-based profiles registry. Ann Hematol 2015;94:651–61. 10.1007/s00277-014-2264-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value--the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2079–81. 10.1056/NEJMp1312287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. News: implementation update. 2015. http://www.ichom.org/news/december-2015-implementation-update/ (accessed 19 May 2017).

- 25.Arora J, Haj M. Implementing ICHOM’s Standard sets of outcomes: cleft lip and palate at Erasmus University Medical Centre in the Netherlands. London: UK Int Consort Heal Outcomes Meas, 2016:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arora J, Lewis S, Cahill A. Implementing ICHOM’s standard sets of outcomes: parkinson’s disease at Aneurin Bevan University Health Board in South Wales, Uk. London: UK Int Consort Heal Outcomes Meas, 2017:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arora J, Tavella R. Implementing ICHOM’s standard sets of outcomes: coronary artery disease in the coronary angiogram database of South Australia (CADOSA). London: UK Int Consort Heal Outcomes Meas, 2017:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wedding U, Pientka L, Höffken K. Quality-of-life in elderly patients with cancer: a short review. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:2203–10. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, et al. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:652–61. 10.1093/jnci/94.9.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen MA, Groenvold M, Aaronson NK, et al. Development of computerised adaptive testing (CAT) for the EORTC QLQ-C30 dimensions - general approach and initial results for physical functioning. Eur J Cancer 2010;46:1352–8. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.